Published online Aug 6, 2016. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.397

Peer-review started: February 15, 2016

First decision: March 31, 2016

Revised: April 14, 2016

Accepted: May 7, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

Published online: August 6, 2016

Processing time: 168 Days and 15.9 Hours

Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B (IND-B) is a controversial entity among the gastrointestinal neuromuscular disorders. It may occur alone or associated with other neuropathies, such as Hirschsprung’s disease (HD). Chronic constipation is the most common clinical manifestation of patients. IND-B primarily affects young children and mimics HD, but has its own histopathologic features characterized mainly by hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexus. Thus, IND-B should be included in the differential diagnoses of organic causes of constipation. In recent years, an increasing number of cases of IND-B in adults have also been described, some presenting severe constipation since childhood and others with the onset of symptoms at adulthood. Despite the intense scientific research in the last decades, there are still knowledge gaps regarding definition, pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities for IND-B. However, in medical practice, we continue to encounter patients with severe constipation or intestinal obstruction who undergo to diagnostic investigation for HD and their rectal biopsies present hyperganglionosis in the submucosal nerve plexus and other features, consistent with the diagnosis of IND-B. This review critically discusses aspects related to the disease definitions, pathophysiology and genetics, epidemiology distribution, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities of this still little-known organic cause of intestinal chronic constipation.

Core tip: Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B (IND-B) is a controversial entity among the gastrointestinal neuromuscular disorders. Chronic constipation is the most common clinical manifestation of patients. IND-B primarily affects young children and mimics Hirschsprung’s disease, but has its own histopathologic features characterized mainly by hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexus. Despite the intense scientific research in the last decades, there are still knowledge gaps regarding IND-B. This review critically discusses aspects related to the disease definitions, pathophysiology and genetics, epidemiology distribution, clinical presentation, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities of this still little-known organic cause of intestinal chronic constipation.

- Citation: Toledo de Arruda Lourenção PL, Terra SA, Ortolan EVP, Rodrigues MAM. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B: A still little known diagnosis for organic causes of intestinal chronic constipation. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7(3): 397-405

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v7/i3/397.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i3.397

Intestinal neuronal dysplasia (IND) is a pathological condition that affects the intestinal submucosal nerve plexuses and may occur alone or associated with other neuropathies, such as Hirschsprung’s disease (HD). IND belongs to the group of the gastrointestinal neuromuscular diseases and was most recently included in the classification for this heterogeneous group of complex changes in the enteric nervous system[1,2].

More than 40 years after its original description[3], the pathology of IND remains incompletely elucidated. Commonly, IND is associated with clinical symptoms of intestinal chronic constipation that affect children in their first years of life, similar to those of HD, but IND has its own histopathologic features characterized by hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexus[4].

Despite the intense scientific research performed in the last decades which includes more than 250 published scientific articles, there are still gaps in the knowledge on IND’s definition, pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities[2,5,6].

The term IND was first used by Nezelof et al[7] in 1970 to describe three cases of congenital megacolon associated with hyperplasia of the myenteric nerve plexus. One year later, Meier-Ruge presented the first formal description of IND as a condition that is typically associated with low intestinal obstruction and that could resemble HD but with distinctive histopathological features, such as hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexuses and increased Acetylcholinesterase activity (AchE) in the parasympathetic nerve fibers in the lamina propria of the mucosa[3].

In 1977, Puri et al[8] described one case of IND associated with HD with rectosigmoid aganglionosis of the nerve plexus and IND in the descending and transverse colon.

In 1983, Fadda et al[9] proposed the classification of two clinical and histopathological subtypes of IND: IND type A (IND-A), an extremely rare form, characterized by congenital hypoplasia of the adrenergic enteric nervous system; and IND type B (IND-B), characterized by malformation of the cholinergic submucosal plexus, accounting for more than 95% of all cases.

In 1990, a consensus meeting in Frankfurt, Germany, defined the morphological criteria for the diagnosis of IND-B[10]. Since that time, these criteria have been widely used both in clinical practice, follow-up studies and genetic investigations[5,11-15]. Furthermore, in the 90s, new criteria were proposed that gave greater importance to the need for the identification of giant ganglia in the submucosa for the diagnosis of IND-B[16,17]. In the several published criteria, the giant ganglia are defined by the presence of a minimum number of ganglion cells ranging from 6 to more than 10 per ganglion[6,18-21].

Given this lack of diagnostic standardization, in 2004, Meier-Ruge et al[5,22] proposed quantitative criteria for the histopathologic diagnosis of IND-B. They defined IND-B by the presence of at least 20% giant nerve ganglia in the submucosa, with more than 8 ganglion cells each, based on the examination of a minimum of 25 submucosal ganglia. Additionally, they used a histochemical panel in frozen sections for the analyses of lactate dehydrogenase, succinyl dehydrogenase and nitric oxide synthase[5,22].

All of these changes in the proposed histopathological criteria for the diagnosis of IND-B have not only caused disparities in its definitions but also skepticism about its existence. The main unsolved problem highlighted in recent publications is if there is a causal relationship between the histological findings and clinical symptoms that would justify the characterization of IND-B as a specific entity[2,4,6,23]. Regarding this situation, the current opinions converge on the need for further research to elucidate the many uncertainties about the clinical and morphological characterization of IND-B[2,4,24].

Two forms of IND are recognized[9]. IND-A is extremely rare and occurs in less than 5% of all IND cases. Patients with IND-A typically present in the neonatal period with symptoms may vary from acute intestinal obstruction to diarrhea with hemorrhagic stools. IND-A is characterized by hypoplasia or aplasia of the adrenergic enteric nervous system[6,25]. A moderate increase in the acetylcholinesterase activity of the parasympathetic nerves is the reason that such cases are termed IND. In 2005, Meier-Ruge and Bruder[26] considered IND-A to be as a necrotizing enterocolitis caused by immaturity of the sympathetic nervous system of the distal colon. The sympathetic innervation is decreased to different degrees in these patients. The absence of sympathetic synapses within the ganglia of the myenteric plexus and the resultant increase in parasympathetic tone are considered to be responsible for the focal colon spasms. Disorders of blood flow and decreased mucus production seem to be the major factors in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. In the majority of cases, the sympathetic innervation is normal by the eighth month of age. Cases that do not present with this development until 10 mo old may be related to sympathetic aplasia[26].

In contrast, IND-B represents more than 95% of all cases, which explains why this entity has been more frequently studied in the literature and why many authors consider IND to be a synonym for IND-B[2]. IND-B is characterized by hyperplasia of the parasympathetic submucosal plexuses. Typical histological features of IND-B include hyperganglionosis, giant ganglia, ectopic ganglion cells and increased AChE activity in the lamina propria and around the submucosal blood vessels. The changes associated with IND-B are more common in the distal colon; however, they can affect any segment of the enteric nervous system and occur in different age groups ranging from newborns to adults and alone or in combination with HD[5]. Subtype B can cause severe constipation in childhood, unresponsive to clinical management and can be associated with soiling and hemorrhagic stools, acute bowel obstruction or enterocolitis episodes. Occasionally, IND-B symptoms mimic those of HD, which is its main differential diagnosis. All IND cases associated with HD are of the B subtype[1,4,6,26].

In 2007, Granero Cendón et al[27] estimated the incidence of IND-B as approximately 1 per 7500 newborns. However, the frequency of IND-B varies widely, and the reported rates range from 0.3% to 40% of all rectal suction biopsies[5,28-30]. This wide variation may be attributable to the lack of consensus on the diagnostic criteria[6,31]. There is also an irregular geographical distribution; the highest rates of diagnosis are in European countries, which can be explained by the fact that the majority of the published research comes from this continent[32].

The latest published series by Taguchi et al[33] (2014) involved a retrospective multicenter study of cases of IND-B in 167 centers in Japan from 2000 to 2009. These authors reported 13 cases based on standardized morphologic criteria from all of the included centers[33]. However, when the quantitative criteria of Meier-Ruge et al[5,22] were applied, only 4 of the 13 cases sustained the IND-B diagnosis.

IND proximal to a segment of aganglionosis is not uncommon and has been suggested to be a possible cause of persistent bowel problems after surgery for HD. This association may occur in 6% to 44% of HD patients[5,28,34,35].

Recent studies have addressed the role of genetic and molecular commands in the migration and development of the neuroenteric cells[36,37]. The proto-oncogene rearranged during transfection (RET) and RET protein act in the migration and proliferation of neuroblasts. Approximately 50% of patients with familial HD present RET proto-oncogenic mutations. This finding highlights the importance of this gene alteration in the pathogenesis of dysganglionosis[36]. Over 20 different mutations have been described in this proto-oncogene, and some of the polymorphisms are associated with particular phenotypes, such as the extension of the aganglionic segment in HD[37].

Similarly, the existence of a genetic component potentially responsible for IND-B has been investigated. The evidence for this component came from a study of monozygotic twins affected by the disease and reports of families in which several members had the histopathological diagnoses of IND-B over multiple generations[14,38]. Because IND-B and HD are derived from the enteric nervous system, changes often occur simultaneously in the same patient, and common molecular pathways are likely to be involved in the geneses of the two pathological conditions[39]. However, mutations in genes considered to be most relevant to HD, such as RET, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and other selected genes in patients with IND-B, have not yet been identified in patients with IND-B[40-44]. Only some combinations of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the RET proto-oncogene have been identified in patients with IND-B[45].

IND-B has been described in some families with other associated congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract, such as intestinal malrotation and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2[15,30,46,47]. Recently, twins from a Turkish family who presented with IND-B associated with congenital short bowel syndrome were described[48], which raises the possibility that mutations in the Coxsackie- and adenovirus receptor-like membrane protein (CLMP) gene could be related to IND-B because CLMP is essential for intestinal development, and its expression is related to molecular junctional adhesion[46].

Different experimental studies in rats and mice have demonstrated that homozygous animals deficient in the NCX/Hox11L.1 gene present with megacolon and hyperplasia of the myenteric nerve plexus[49-52]. However, Costa et al[14] (2000) and Fava et al[42] (2002) failed to demonstrate the presence of mutations or molecular defects in the Hox11L.1 coding region in humans with IND-B.

Another possible genetic mechanism is related to endothelin receptor B[31]. One of the endothelin receptors (END3) plays an important role in the development of the enteric nervous system of mice. Holland-Cunz et al[53] (2003) reported that mice presenting with a heterozygous deficiency in this receptor exhibit histopathological changes similar to IND-B, although they do not exhibit clinical signs of bowel dysmotility. These findings were also not reproducible in human research.

The pathogenesis is also a part of the array of uncertainties regarding IND-B. Several hypotheses have been discussed, although none are widely accepted[6,24].

The histopathological changes that characterize IND-B may come from a genetically primary change that directly influences the embryological development of tissues derived from the neural crest[6]. However, these findings have only been identified in experimental studies[14,49-52]. This hypothesis is supported by the association with other intestinal and extra-intestinal congenital anomalies[15,54,55].

Another research line conceives IND-B as an adaptive response of the enteric nervous system. IND-B has been considered to be secondary to acquired phenomena caused by congenital obstructions or inflammation occurred during pre-, peri- or post-natal periods in humans[12,13,18,56,57]. Morphological findings suggestive of IND-B have been observed in intestinal segments proximal to areas of intestinal atresia, rectal mucosal prolapse and ileostomy, intestinal intussusception, imperforate anus and necrotizing enterocolitis[56,58,59]. This secondary histopathologic response to a bowel obstruction has also been tested in experimental studies with conflicting results[60-62]. Pickard et al[60] (1981) observed ganglionic hyperplasia in the dilated segment of the proximal jejunum in an experimental model of intestinal atresia in sheep fetuses. The same results were not reproduced by Moore et al[61] (1993) in a model of partial colon obstruction in adult rats. These authors observed a decrease in the number of ganglion cells in the myenteric nerve plexuses of rats submitted to partial intestinal obstruction. This decrease was explained by an increase in colonic diameter secondary to bowel obstruction[61]. The most recent study on this subject was from Gálvez et al[62] (2004) who identified histopathological changes suggestive of IND-B in some adult rats in a model of chronic colonic obstruction.

An association between IND-B and HD has also been reported[8,35,63-65]. In such cases, the segments proximal to the aganglionic obstructed segment present histological characteristics of IND-B[6,54]. Thus, these morphological changes of the nerve plexuses of the proximal submucosa segment can be explained both by a primary embryonic modification of the enteric nervous system that could be considered a neurocristopathy that shares a common origin with HD and by a minor change in response to a distal intestinal obstruction[54,63-66].

There is also some evidence that the histopathological changes observed in IND-B can be part of the normal development of the enteric nervous system. As a patient gets older, there is an increase in the size of the ganglion cells and a decrease in their number in the submucosal nerve plexuses[5,22,67-69].

Another conflicting issue is related to whether a cause-effect relationship exists between the histopathological findings of IND-B and the clinical symptoms. In most cases, the diagnosis of IND-B is based on histopathological examinations of rectal biopsies from patients who presented severe constipation[6]. However, histopathological changes similar to those of IND-B have been found in the colon of 36 completely asymptomatic children[69]. Other studies have failed to demonstrate correlations between the histopathological findings, clinical symptoms, radiological and manometric changes[11,12,47,67]. These controversies support the authors who do not consider IND-B as a distinct entity but rather a histopathological alteration of the enteric nervous system that may or may not cause clinical manifestations[6,23,24,64].

Intestinal chronic constipation has been reported as the commonest clinical presentation in IND-B case series[6,57]. In addition to the decrease in bowel movement frequency, the presence of straining at stool, bulky and hardened stools, fecal overflow incontinence and rectal bleeding are usually present as signs and symptoms of chronic constipation[70,71]. Therefore, IND-B must be part of the differential diagnosis of possible organic causes for constipation in childhood[72].

In some cases, these symptoms may begin in the first years of life with delays in meconium passage, abdominal distension, vomiting and failure to thrive[73,74]. A portion of patients continue to exhibit symptoms throughout life and frequently present with severe constipation unresponsive to several treatment modalities[75-77]. These symptoms may improve after 4 years of age, which supports the hypothesis of maturation of the enteric nervous system early in life, since in these cases the histopathological findings of IND-B could disappear concurrently with the symptoms[5].

Severe symptoms, such as enterocolitis episodes, bowel obstruction, volvulus and intussusceptions are rare complications described in different age groups[78-81]. In recent years, an increasing number of cases of IND-B in adults have been described[82-86]. Some of these cases have exhibited symptoms of severe constipation since childhood[82,83], whereas others experienced the onset of symptoms at adulthood[84]. Some patients develop serious complications, such as chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, acute bowel obstruction or intestinal infarction[84-86]. The oldest reported patient received a confirmed diagnosis at 71 years of age[83].

The diagnostic workup used in patients with IND-B must be the same routinely performed during investigation for organic causes of intestinal constipation, particularly focused to exclude HD, which is the most prevalent intestinal dysganglionosis[6,57,72,87]. However, anorectal manometry and barium enema, which are established tests for HD screening, do not present specific results for IND-B[88,89]. Barium enema frequently demonstrate an increased caliber of the rectosigmoid, which is a nonspecific finding typical of patients with constipation, but also may demonstrate conical transition zone, similar to HD[31,89]. Anorectal manometry can reveal absence or presence of an anorectal inhibitory reflex, commonly with atypical morphology, which contributes little to the diagnostic investigation of IND-B[5,31,89].

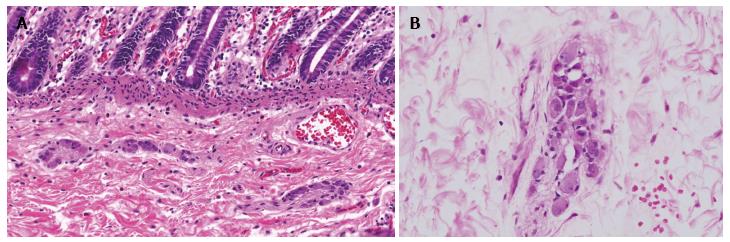

Thus, the diagnosis of IND-B essentially relays on histopathological analyses of rectal biopsies[2,4]. The morphological criteria for its diagnosis have changed substantially over the years, leading to difficulties for clinical practice and comparisons between studies. Hyperplasia of the submucosal nerve plexuses is the morphological finding that defines IND-B but that is characterized in different manners according to the adopted criterion[5]. Some authors emphasize the need for the presence of a minimum number of ganglion cells per ganglion or a minimum number of ganglia with these characteristics among the analyzed ganglia for a diagnosis of plexuses hyperplasia[16,22,75,90] (Figure 1). Other morphological features, such as the presence of ectopic ganglion cells, increased acetylcholinesterase activity, ganglion cells with a “button” appearance and hypertrophy of the nerve trunks, are considered diagnostic criteria in some studies[9,10,16,68,79,91].

The criteria described by Meier-Ruge et al[22] (2004) and slightly altered by Meier-Rouge et al[5] (2006) suggest a quantitative analysis of the number of ganglion cells in the nervous submucosal plexuses and the identification of at least 20% giant ganglia with at least 8 neurons each, in 25 analyzed nerve ganglia. Frozen 15-μm-thick sections are mandatory and must be subjected to a panel of histochemical tests for lactate dehydrogenase, succinyl dehydrogenase and nitric oxide synthase, and the patient must be older than 1 year of age[5,22]. Although these criteria have been accepted by the scientific community, there are few reports of their use in large series of patients with IND-B[33]. The requirement for fresh frozen sections and the fact that the specific histochemical stainings are not available in most pediatric pathology laboratories are limitations that must be considered. Moreover, it is uncertain whether the numerical criteria applied in these analyses can be applied to 5-μm-thick histological sections embedded in paraffin for standard histological analyses with hematoxylin and eosin or immunohistochemical methods[2,5].

Given the numerous uncertainties about the definition, pathogenesis and diagnosis of IND, the lack of consensus regarding its treatment is not surprising. Patients with IND have been subjected to different treatments modalities, that may vary from clinical management, to surgical procedures[57].

Clinical management includes dietary changes, laxatives and enemas[6,32]. Schimpl et al[32] (2004) reported satisfactory results in 80% of 105 patients treated with dietary changes, cisapride, laxatives and enemas, in a median follow up period of 7.2 years. Clinical management must follow the currently used guidelines for the treatment of intestinal chronic constipation in children, including fecal desimpaction and laxatives[72].

Although there is not a well-established role to surgical treatment as in Hirshcprung’s disease, there are some reports of this modality of treatment in IND-B[83]. Surgical treatment can be performed through different techniques[11,46,63,92]. Schärli[11] (1992) reported favorable results with a posterior sphincteromyotomy in 13 patients, after a limited 6 mo follow-up period. Some case series with a small number of patients showed symptoms improvement after a temporary colostomy[6,46,63]. Several reports described a colonic resection in patients with IND-B, commonly performed by an anal pull-through procedure. In most of the cases, there were improvement in the number of bowel movements and in the obstructive symptoms. However, the time of follow-up, the surgical techniques and the length of the resected bowel are quite variable[5,77,92].

The results obtained with these different types of treatment are very discordant. Long-term follow-up studies are lacking and the available studies involve limited numbers of patients[32,57,75]. Thus, the available data nowadays still remains too scarce to establish a therapeutic guideline for IND-B[32,57]. On the other hand, there is a real disease, with its own clinical manifestations and can not be classified only as an histopathological entity[75].

The several types of clinical manifestations directly influence in the treatment. Cases of mild intestinal constipation, without systemic complications or obstructive symptoms, tend to be treated with a conservative clinical management. Most of these cases may resolve spontaneously up to the age of 4 years, due to the maturation of the enteric nervous system[93]. On the other hand, IND-B may present with severe intestinal constipation, with infectious and obstructive symptoms, what require a more invasive treatment[77,91]. Therefore, there is a tendency to consider the conservative choice as a first line therapy in IND-B. The surgical treatment through intestinal resections should be reserved for the cases refractory to at least 6 mo of clinical management, or in the presence of obstructive complications[5,6,31,32,76].

IND-B can be considered as a pathological entity characterized by anomalies of the submucous plexus, with a considerable increase in the number of ganglion cells, commonly associated with different degrees of constipation in childhood. IND-B remains surrounded by controversies related to its definition, etiopathogenesis, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities. However, in medical practice, we continue to encounter children with severe constipation or intestinal obstruction who undergo to diagnostic investigation for HD and rectal biopsies show hyperplastic submucosal ganglia consistent with the diagnosis of IND-B.

In this context, it is of utmost importance to maintain our efforts to clarify the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of this still little-known organic cause of intestinal chronic constipation.

| 1. | Knowles CH, De Giorgio R, Kapur RP, Bruder E, Farrugia G, Geboes K, Lindberg G, Martin JE, Meier-Ruge WA, Milla PJ. The London Classification of gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology: report on behalf of the Gastro 2009 International Working Group. Gut. 2010;59:882-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Schäppi MG, Staiano A, Milla PJ, Smith VV, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, Mearin ML, Papadopoulou A, Ruemmele FM. A practical guide for the diagnosis of primary enteric nervous system disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:677-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Meier-Ruge W. [Casuistic of colon disorder with symptoms of Hirschsprung’s disease (author’s transl)]. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1971;55:506-510. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Friedmacher F, Puri P. Classification and diagnostic criteria of variants of Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:855-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meier-Ruge WA, Bruder E, Kapur RP. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B: one giant ganglion is not good enough. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2006;9:444-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Holschneider AM, Puri P, Homrighausen LH, Meier-Ruge W. Intestinal Neuronal Malformation (IND): Clinical Experience and Treatment. Hirschsprung’s disease and allied disorders. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer 2008; 229-251. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Nezelof C, Guy-Grand D, Thomine E. [Megacolon with hyperplasia of the myenteric plexua. An anatomo-clinical entity, apropos of 3 cases]. Presse Med. 1970;78:1501-1506. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Puri P, Lake BD, Nixon HH, Mishalany H, Claireaux AE. Neuronal colonic dysplasia: an unusual association of Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fadda B, Maier WA, Meier-Ruge W, Schärli A, Daum R. [Neuronal intestinal dysplasia. Critical 10-years’ analysis of clinical and biopsy diagnosis]. Z Kinderchir. 1983;38:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Borchard F, Meier-Ruge W, Wiebecke B, Briner J, Müntefering H, Födisch HF, Holschneider AM, Schmidt A, Enck P, Stolte M. [Disorders of the innervation of the large intestine--classification and diagnosis. Results of a consensus conference of the Society of Gastroenteropathology 1 December 1990 in Frankfurt/Main]. Pathologe. 1991;12:171-174. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Schärli AF. [Intestinal neuronal dysplasia]. Cir Pediatr. 1992;5:64-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Koletzko S, Ballauff A, Hadziselimovic F, Enck P. Is histological diagnosis of neuronal intestinal dysplasia related to clinical and manometric findings in constipated children? Results of a pilot study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:59-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sacher P, Briner J, Hanimann B. Is neuronal intestinal dysplasia (NID) a primary disease or a secondary phenomenon? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1993;3:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Costa M, Fava M, Seri M, Cusano R, Sancandi M, Forabosco P, Lerone M, Martucciello G, Romeo G, Ceccherini I. Evaluation of the HOX11L1 gene as a candidate for congenital disorders of intestinal innervation. J Med Genet. 2000;37:E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Martucciello G, Torre M, Pini Prato A, Lerone M, Campus R, Leggio S, Jasonni V. Associated anomalies in intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meier-Ruge WA, Brönnimann PB, Gambazzi F, Schmid PC, Schmidt CP, Stoss F. Histopathological criteria for intestinal neuronal dysplasia of the submucosal plexus (type B). Virchows Arch. 1995;426:549-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Meier-Ruge WA, Schmidt PC, Stoss FS. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia and its morphometric evidences. Pediatr Surg Int. 1995;10: 447-453. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schofield DE, Yunis EJ. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12:182-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Moore SW, Laing D, Kaschula RO, Cywes S. A histological grading system for the evaluation of co-existing NID with Hirschsprung’s disease. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1994;4:293-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kobayashi H, Hirakawa H, Puri P. What are the diagnostic criteria for intestinal neuronal dysplasia? Pediatr Surg Int. 1995;10:459-464. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mahesha V, Saikia UN, Shubha AV, Rao KL. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia of the myenteric plexus--new entity in humans? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008;18:59-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meier-Ruge WA, Ammann K, Bruder E, Holschneider AM, Schärli AF, Schmittenbecher PP, Stoss F. Updated results on intestinal neuronal dysplasia (IND B). Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:384-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | de la Torre Mondragón L, Reyes-Múgica M. R.I.P. for IND B. Pediatr and Develop Pathol. 2006;9:425-426. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Martucciello G, Pini Prato A, Puri P, Holschneider AM, Meier-Ruge W, Jasonni V, Tovar JA, Grosfeld JL. Controversies concerning diagnostic guidelines for anomalies of the enteric nervous system: a report from the fourth International Symposium on Hirschsprung’s disease and related neurocristopathies. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1527-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aydın H, Şenaylı A, Mehmet Kışlal F, Sarıcı D, Köseoğlu B, Güreşçi S. Coexistence of Anal Atresia, Anophthalmia and Intestinal Neuronal Dysplasia Type-A in a Newborn. J Neonatal Surg. 2015;4:44. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Meier-Ruge WA, Bruder E. Different colon diseases with chronic constipation. Histopathology of Chronic Constipation. Basel Switzerland: Karger 2005; 3-32. |

| 27. | Granero Cendón R, Millán López A, Moya Jiménez MJ, López Alonso M, De Agustín Asensio JC. [Intestinal neuronal dysplasia: association with digestive malformations]. Cir Pediatr. 2007;20:166-168. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Meier-Ruge W. Epidemiology of congenital innervation defects of the distal colon. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420:171-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Milla PJ, Smith VV. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:356-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Martucciello G, Caffarena PE, Lerone M, Mattioli G, Barabino A, Bisio G, Jasonni V. Neuronal intestinal dysplasia: clinical experience in Italian patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1994;4:287-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Puri P. Intestinal dysganglionosis and other disorders of intestinal motility. Pediatric surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc 2012; 1279-1287. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Schimpl G, Uray E, Ratschek M, Höllwarth ME. Constipation and intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B: a clinical follow-up study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Taguchi T, Kobayashi H, Kanamori Y, Segawa O, Yamataka A, Sugiyama M, Iwanaka T, Shimojima N, Kuroda T, Nakazawa A. Isolated intestinal neuronal dysplasia Type B (IND-B) in Japan: results from a nationwide survey. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:815-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Montedonico S, Cáceres P, Muñoz N, Yáñez H, Ramírez R, Fadda B. Histochemical staining for intestinal dysganglionosis: over 30 years experience with more than 1,500 biopsies. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Swaminathan M, Oron AP, Chatterjee S, Piper H, Cope-Yokoyama S, Chakravarti A, Kapur RP. Intestinal Neuronal Dysplasia-Like Submucosal Ganglion Cell Hyperplasia at the Proximal Margins of Hirschsprung Disease Resections. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2015;18:466-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Amiel J, Sproat-Emison E, Garcia-Barcelo M, Lantieri F, Burzynski G, Borrego S, Pelet A, Arnold S, Miao X, Griseri P. Hirschsprung disease, associated syndromes and genetics: a review. J Med Genet. 2008;45:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Haricharan RN, Georgeson KE. Hirschsprung disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:266-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kobayashi H, Mahomed A, Puri P. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia in twins. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22:398-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sánchez-Mejías A, Fernández RM, Antiñolo G, Borrego S. A new experimental approach is required in the molecular analysis of intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B patients. Exp Ther Med. 2010;1:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Barone V, Weber D, Luo Y, Brancolini V, Devoto M, Romeo G. Exclusion of linkage between RET and neuronal intestinal dysplasia type B. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gath R, Goessling A, Keller KM, Koletzko S, Coerdt W, Müntefering H, Wirth S, Hofstra RM, Mulligan L, Eng C. Analysis of the RET, GDNF, EDN3, and EDNRB genes in patients with intestinal neuronal dysplasia and Hirschsprung disease. Gut. 2001;48:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Fava M, Borghini S, Cinti R, Cusano R, Seri M, Lerone M, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Martucciello G, Ravazzolo R. HOX11L1: a promoter study to evaluate possible expression defects in intestinal motility disorders. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Tou JF, Li MJ, Guan T, Li JC, Zhu XK, Feng ZG. Mutation of RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung’s disease and intestinal neuronal dysplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1136-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Borghini S, Duca MD, Pini Prato A, Lerone M, Martucciello G, Jasonni V, Ravazzolo R, Ceccherini I. Search for pathogenetic variants of the SPRY2 gene in intestinal innervation defects. Intern Med J. 2009;39:335-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Fernández RM, Sánchez-Mejías A, Ruiz-Ferrer MM, López-Alonso M, Antiñolo G, Borrego S. Is the RET proto-oncogene involved in the pathogenesis of intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B? Mol Med Rep. 2009;2:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Rintala R, Rapola J, Louhimo I. Neuronal intestinal dysplasia. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:186-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ure BM, Holschneider AM, Meier-Ruge W. Neuronal intestinal malformations: a retro- and prospective study on 203 patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1994;4:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Van Der Werf CS, Wabbersen TD, Hsiao NH, Paredes J, Etchevers HC, Kroisel PM, Tibboel D, Babarit C, Schreiber RA, Hoffenberg EJ. CLMP is required for intestinal development, and loss-of-function mutations cause congenital short-bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:453-462.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hatano M, Aoki T, Dezawa M, Yusa S, Iitsuka Y, Koseki H, Taniguchi M, Tokuhisa T. A novel pathogenesis of megacolon in Ncx/Hox11L.1 deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:795-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Shirasawa S, Yunker AM, Roth KA, Brown GA, Horning S, Korsmeyer SJ. Enx (Hox11L1)-deficient mice develop myenteric neuronal hyperplasia and megacolon. Nat Med. 1997;3:646-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Yamataka A, Hatano M, Kobayashi H, Wang K, Miyahara K, Sueyoshi N, Miyano T. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia-like pathology in Ncx/Hox11L.1 gene-deficient mice. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1293-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yanai T, Kobayashi H, Yamataka A, Lane GJ, Miyano T, Hayakawa T, Satoh K, Kase Y, Hatano M. Acetylcholine-related bowel dysmotility in homozygous mutant NCX/HOX11L.1-deficient (NCX-/-) mice-evidence that acetylcholine is implicated in causing intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Holland-Cunz S, Krammer HJ, Süss A, Tafazzoli K, Wedel T. Molecular genetics of colorectal motility disorders. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Berger S, Ziebell P, OFFsler M, Hofmann-von Kap-herr S. Congenital malformations and perinatal morbidity associated with intestinal neuronal dysplasia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:474-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Corduk N, Koltuksuz U, Bir F, Karabul M, Herek O, Sarioglu-Buke A. Association of rare intestinal malformations: colonic atresia and intestinal neuronal dysplasia. Adv Ther. 2007;24:1254-1259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Holschneider AM, Pfrommer W, Gerresheim B. Results in the treatment of anorectal malformations with special regard to the histology of the rectal pouch. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1994;4:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Csury L, Peña A. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1995;10:441-446. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 58. | Lumb PD, Moore L. Are giant ganglia a reliable marker of intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B (IND B)? Virchows Arch. 1998;432:103-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zorenkov D, Otto S, Böttner M, Hedderich J, Vollrath O, Ritz JP, Buhr H, Wedel T. Morphological alterations of the enteric nervous system in young male patients with rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1483-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Pickard LR, Santoro S, Wyllie RG, Haller JA. Histochemical studies of experimental fetal intestinal obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Moore SW, Laing D, Melis J, Cywes S. Secondary effects of prolonged intestinal obstruction on the enteric nervous system in the rat. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1196-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Gálvez Y, Skába R, Vajtrová R, Frantlová A, Herget J. Evidence of secondary neuronal intestinal dysplasia in a rat model of chronic intestinal obstruction. J Invest Surg. 2004;17:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Briner J, Oswald HW, Hirsig J, Lehner M. Neuronal intestinal dysplasia--clinical and histochemical findings and its association with Hirschsprung’s disease. Z Kinderchir. 1986;41:282-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Berry CL. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia: does it exist or has it been invented? Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;422:183-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Schmittenbecher PP, Sacher P, Cholewa D, Haberlik A, Menardi G, Moczulski J, Rumlova E, Schuppert W, Ure B. Hirschsprung’s disease and intestinal neuronal dysplasia--a frequent association with implications for the postoperative course. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999;15:553-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Kobayashi H, Yamataka A, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Inflammatory changes secondary to postoperative complications of Hirschsprung’s disease as a cause of histopathologic changes typical of intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:152-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Cord-Udy CL, Smith VV, Ahmed S, Risdon RA, Milla PJ. An evaluation of the role of suction rectal biopsy in the diagnosis of intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:1-6; discussion 7-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Koletzko S, Jesch I, Faus-Kebetaler T, Briner J, Meier-Ruge W, Müntefering H, Coerdt W, Wessel L, Keller KM, Nützenadel W. Rectal biopsy for diagnosis of intestinal neuronal dysplasia in children: a prospective multicentre study on interobserver variation and clinical outcome. Gut. 1999;44:853-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Coerdt W, Michel JS, Rippin G, Kletzki S, Gerein V, Müntefering H, Arnemann J. Quantitative morphometric analysis of the submucous plexus in age-related control groups. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:239-246. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, Davidson GP, Fleisher DF, Taminiau J. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 71. | Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 1091] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 72. | Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Benninga MA. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:258-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Pini-Prato A, Avanzini S, Gentilino V, Martucciello G, Mattioli G, Coccia C, Parodi S, Bisio GM, Jasonni V. Rectal suction biopsy in the workup of childhood chronic constipation: indications and diagnostic value. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:117-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Hirayama Y, Iinuma Y, Numano F, Masui D, Iida H, Komatsuzaki N, Nagayama Y, Naito S, Nitta K. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia-like histopathology in infancy. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Schmittenbecher PP, Glück M, Wiebecke B, Meier-Ruge W. Clinical long-term follow-up results in intestinal neuronal dysplasia (IND). Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Gillick J, Tazawa H, Puri P. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia: results of treatment in 33 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:777-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Mattioli G, Castagnetti M, Martucciello G, Jasonni V. Results of a mechanical Duhamel pull-through for the treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease and intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1349-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Sacher P, Briner J, Stauffer UG. Unusual cases of neuronal intestinal dysplasia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1991;6:225-226. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Montedonico S, Acevedo S, Fadda B. Clinical aspects of intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1772-1774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Peng SS, Lee WT, Hsui WM. An unusual cause of abdominal distension in a 4-year-old boy. Neuronal intestinal dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:e3-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Jáquez-Quintana JO, González-González JA, Arana-Guajardo AC, Larralde-Contreras L, Flores-Gutiérrez JP, Maldonado-Garza HJ. Sigmoid volvulus as a presentation of neuronal intestinal dysplasia type B in an adolescent. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:178-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Voderholzer WA, Wiebecke B, Gerum M, Müller-Lissner SA. Dysplasia of the submucous nerve plexus in slow-transit constipation of adults. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:755-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Vougas V, Vardas K, Christou C, Papadimitriou G, Florou E, Magkou C, Karamanolis D, Manganas D, Drakopoulos S. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B in adults: a controversial entity. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2014;8:7-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Vijayaraghavan R, Chandrashekar R, Melkote Jyotiprakash A, Kumar R, Rashmi MV, Shanmukhappa Belagavi C. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia (type B) causing fatal small bowel ischaemia in an adult: a case report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:773-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | López Sanclemente MC, Castellvi J, Ortiz de Zárate L, Barrios P. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia in a patient with chronic colonic pseudo-obstruction. Cir Esp. 2014;92:e59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Junquera Bañares S, Oria Mundín E, Córdoba Iturriagagoitia A, Botella-Carretero JJ. [Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction due to intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B (IND B), concerning one case]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2014;37:157-164. [PubMed] |

| 87. | Wu XJ, Zhang HY, Li N, Yan MS, Wei J, Yu DH, Feng JX. A new diagnostic scoring system to differentiate Hirschsprung’s disease from Hirschsprung’s disease-allied disorders in patients with suspected intestinal dysganglionosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:689-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | de Lorijn F, Kremer LC, Reitsma JB, Benninga MA. Diagnostic tests in Hirschsprung disease: a systematic review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:496-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Gil-Vernet JM, Broto J, Guillén G. [Hirschsprung-neurointestinal dyspasia: diferential diagnosis and reliability of diagnostic procedures]. Cir Pediatr. 2006;19:91-94. [PubMed] |

| 90. | Meier-Ruge WA. Histological diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease. Hirschsprung’s disease and allied disorders. London: Harwood 1999; 252-265. |

| 91. | Munakata K, Morita K, Okabe I, Sueoka H. Clinical and histologic studies of neuronal intestinal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Tang ST, Yang Y, Wang GB, Tong QS, Mao YZ, Wang Y, Li SW, Ruan QL. Laparoscopic extensive colectomy with transanal Soave pull-through for intestinal neuronal dysplasia in 17 children. World J Pediatr. 2010;6:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Bruder E, Meier-Ruge WA. [Intestinal neuronal dysplasia type B: how do we understand it today?]. Pathologe. 2007;28:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript Source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of Origin: Brazil

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El-Shabrawi MH, Li YY, Vermorken A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ