Published online Nov 6, 2015. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.248

Peer-review started: March 28, 2015

First decision: May 13, 2015

Revised: June 29, 2015

Accepted: August 30, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: November 6, 2015

Processing time: 229 Days and 15.1 Hours

Bleeding from duodenal varices is reported to be a catastrophic and often fatal event. Most of the cases in the literature involve patients with underlying cirrhosis. However, approximately one quarter of duodenal variceal bleeds is caused by extrahepatic portal hypertension and they represent a unique population given their lack of liver dysfunction. The authors present a case where a 61-year-old male with history of remote crush injury presented with bright red blood per rectum and was found to have bleeding from massive duodenal varices. Injection sclerotherapy with ethanolamine was performed and the patient experienced a favorable outcome with near resolution of his varices on endoscopic follow-up. The authors conclude that sclerotherapy is a reasonable first line therapy and review the literature surrounding the treatment of duodenal varices secondary to extrahepatic portal hypertension.

Core tip: Bleeding from duodenal varices is a gastrointestinal emergency and focused patient history may help the clinician to suspect this life threatening diagnosis. Clinician’s need to have a high degree of suspicion for bleeding varices even in the absence of known cirrhosis if certain clinical characteristics are present, such as history of crush injury. If duodenal varices are diagnosed on endoscopy, endoscopic injection sclerotherapy can be a highly successful definitive intervention. The authors suggest ethanolamine injection sclerotherapy, though multiple alternative sclerosants are also established in the literature as are other therapeutic alternatives including endoscopic band ligation. With prompt endoscopic management, life threatening bleeding can be effectively mitigated and with the expectation of excellent long term outcomes.

- Citation: Steevens C, Abdalla M, Kothari TH, Kaul V, Kothari S. Massive duodenal variceal bleed; complication of extra hepatic portal hypertension: Endoscopic management and literature review. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2015; 6(4): 248-252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v6/i4/248.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.248

Bleeding from duodenal varices is a rare but potentially fatal condition. A gastroenterologist will encounter these only rarely as they represent only about 0.4% of all variceal bleeding[1], yet the traditionally reported mortality approaches 40%[2], underscoring the importance of prompt and effective management. While there have been hundreds of cases reported, most describe bleeding varices secondary to cirrhosis or intrahepatic portal hypertension. This gap in the literature largely excludes the 25% of duodenal variceal bleeds which are caused by extrahepatic portal hypertension[3]. The varices that result from localized vascular hypertension may respond differently to endoscopic interventions and ultimately experience different outcomes given their normal central portal pressures and lack of underlying liver dysfunction. Proven endoscopic interventions include endoscopic band ligation (EVL) or endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS). We present a case of profound gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding from duodenal varices in a patient with mesenteric vein obstruction, which was successfully managed with a single episode of EIS with ethanolamine, and review the present literature in an attempt to clarify the effectiveness of available endoscopic interventions for extrahepatic portal hypertension.

A 61-year-old male was referred for recurrent GI bleeding. The presentation to an outside hospital one day prior had been notable for sudden onset of melena and bright red blood per rectum (BRBPR). His medical history included coronary artery disease; gastroesophageal reflux disease and a remote crush injury with partial small bowel resection. There was no previous GI bleeding, liver disease, alcohol intake, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and his medications were significant only for aspirin 81 mg daily. Initially, he had tachycardia to 123 beats per minute with a benign abdominal examination and gross blood on rectal exam. Hematocrit was 35% with platelet count of 99000/uL, and international normalized ratio 1.1. He underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed extensive duodenal varices. Follow-up angiography of the portal system had unremarkable arterial vasculature, but abnormal venous anatomy significant for occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein with extensive collateral formation.

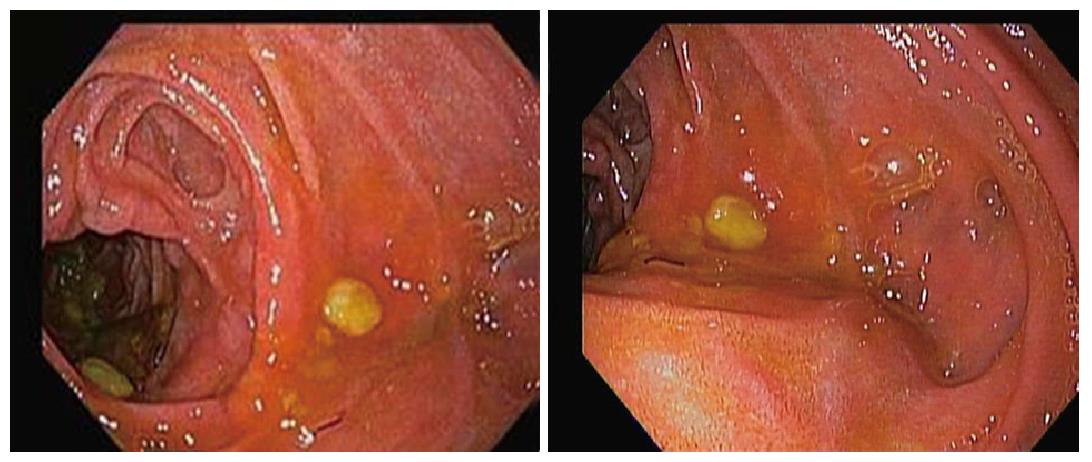

Due to the complexity and risk of definitive intervention, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care center. At the time of transfer, he had received 7 units of packed red blood cells and was being medically treated with pantoprazole and octreotide drips. Intensive care unit (ICU) admission was required; at that time he remained tachycardic with continued BRBPR and his hematocrit had fallen to 22%. Repeat EGD visualized a deformed duodenum with large varices present in the second and third portion with stigmata of recent bleeding (Figure 1). The decision to intervene with injection sclerotherapy was made and 4 mL of 5% ethanolamine was injected with satisfactory hemostasis. There were no episodes of re-bleeding and he was discharged 5 d later. Follow-up EGD at one month showed near complete resolution of the duodenal varices, which was persistent at his follow up EGD 20 mo after the initial presentation (Figure 2).

Duodenal varices in extrahepatic portal hypertension are likely much more common than currently recognized considering that only about 65% of patients with the condition will present with GI bleeding[3]. In the absence of cirrhosis or active hemorrhage, patients with asymptomatic duodenal varices may never receive portal system imaging or upper endoscopy. Recognized etiologies of extrahepatic portal hypertension leading to duodenal varices include pancreatitis, omphalophlebitis, intra-abdominal tumors, previous surgery, retroperitoneal fibrosis and portal/splenic vein thrombosis among others[3]. Our case is the second noting the association of remote crush injury with a late presenting duodenal variceal bleed[4]. The vessels injured by this type of trauma may be especially prone to stenosis or obstruction during the healing process. Regardless of the inciting injury, the varices result from collateral venous vessel formation around the obstruction in an attempt to maintain hepatopedal blood flow[5]. Bleeding from this anomalous vasculature represents a GI emergency.

The acute bleeding episode from duodenal varices is massive; an average of 10.4 units of packed red cells is transfused during these bleeds[6]. Prompt endoscopic diagnosis and management is crucial to achieving a successful outcome. Deformity of the duodenum with radiography or endoscopy can provide clues to the presence of duodenal varices, thus prompting the endoscopist to carefully scrutinize this location. The duodenal bulb is the most common location for them to occur although varices can be present in any portion[7]. The location of the varices within the duodenum could depend on the inciting injury. Both our case and a previous case in the literature note bleeding from the second portion of the duodenum in a patient with history of crush injury[4]. Once the diagnosis is made and the patient is sufficiently stabilized, a number of interventional options exist.

Endoscopic therapy for bleeding duodenal varices emerged with sclerotherapy in the early 1980’s[8] and EVL in the mid 1990’s[9]. Since then, there have been only a handful of endoscopically managed duodenal variceal bleeds caused by extrahepatic portal hypertension (Table 1). These cases demonstrate a wide variety of etiologies, but vascular abnormalities underlie most of them. Duodenal varices in general have unique anatomy, which must be taken into account when choosing endoscopic therapy. The varix consists of a single afferent vessel, arising from either the superior or inferior pacreaticoduodenal vein, and a single efferent vessel, which drains into the inferior vena cava. Though visible, the varix is typically buried deep into the submucosa[1]. This anatomy may render the varices difficult to fully eradicate and explain some of the late re-bleeding noted in Table 1.

| Ref. | Etiology/clinical history | Intervention | Outcome | Additional |

| Bosch et al[10] | Mesenteric vein thrombosis | EVL | Stable (11 mo) | |

| Goetz et al[11] | Post-trauma splenectomy | EVL | Stable (4 mo) | |

| Gunnerson et al[4] | Crush injury | EVL | Stable (2 yr) | |

| Gunnerson et al[4] | Anomalous venous vasculature | EVL | Re-bleed (8 mo) | EIS; (Sod mon) |

| Cottam et al[12] | Multiple surgical procedures | EIS; (Epi) | Re-bleed (wk) | Surgery |

| Osaka et al[13] | Vascular malformation | EIS; (Eth) | Re-bleed (unknown) | Surgery |

| Tsuji et al[14] | Motor vehicle accident | EIS; (Polid, Throm) | Stable (unknown) | Surgery |

| Sans et al[15] | Caroli’s Dz, SMV thrombosis | EIS; (Thromb, Eth) | Stable (5 mo) | |

| Kao et al[16] | Pancreatitis; portal vein stenosis | EIS; (Cyano, Lip) | Stable (2 mo) |

Our case was successfully managed with ethanolamine injection sclerotherapy and the patient did not experience re-bleeding. To our knowledge, this is only the third reported case of ethanolamine sclerotherapy for bleeding duodenal varices caused by extrahepatic portal hypertension.

There are potential concerns and complications to consider when choosing ethanolamine sclerotherapy in the duodenum. The thin duodenal wall and its risk of perforation are cited as potential complications. Indeed, there are case reports of duodenal perforation after multiple episodes sclerotherapy for a duodenal ulcer[17], but no similar reports exist for the use of sclerotherapy for duodenal varices. Another sclerotherapy option, cyanoacrylate, was carefully considered for treatment of these bleeding duodenal varices. Cyanoacrylate has been very effective for the treatment of gastric varices and a case series of bleeding duodenal varices caused by intrahepatic portal hypertension noted success in 4 out of 4 patients[18]. This agent has its own set of risks associated with its use, most notably being distant embolization during treatment of the duodenal varix[19]; for this reason, we typically invoke an informed consent discussion prior to cyanoacrylate injection which was not possible in this particular case. Outside of sclerotherapy, endoscopic band ligation is the other major endoscopic intervention used for the treatment of bleeding duodenal varices. Significant theoretical risks are also associated with EVL. In porcine models, duodenal banding demonstrated a 100% perforation rate[20]. Additionally, it is suggested that if the entire varix cannot be banded at the time of intervention, there is the risk of creating a wide defect with re-bleeding after sloughing occurs[21]. To mitigate these risks, some authors have previously recommended additional procedures such as balloon occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration following EVL[9]. The cases reported in the current literature do not support these fears; from the few case reports available, EVL appears to be safe and effective with only one episode of late re-bleeding at 8 mo[4]. The ultimate choice of endoscopic intervention will depend on the clinical scenario, endoscopist expertise and local practice patterns.

Our patient’s presentation was typical for duodenal variceal bleeding. He had a remote history of intra-abdominal injury and presented with a hemodynamically unstable GI bleed requiring ICU care. In the acute presentation, we contend that proceeding with a sclerosant such as ethanolamine is a reasonable and safe first line approach given its limited risk profile and proven success. With prompt stabilization and intervention, he experienced a good outcome, which appears typical for duodenal variceal bleeds secondary to extrahepatic portal hypertension. Given the resolution of his varices on repeat endoscopy, his prognosis is likely excellent. This case demonstrates that duodenal variceal bleeds caused by extrahepatic portal hypertension have unique clinical history and physiology. They respond well to intervention and good outcomes should be expected with prompt and effective management.

A 61-year-old man presented with melena and bright red blood per rectum.

On examination, he was noted to be tachycardic but with benign abdominal examination and gross blood on digital rectal examination.

With the reported melena and hemodynamic instability, massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding was suspected and the differential diagnosis included peptic ulcer disease, esophageal/gastric varices or dieulafoy lesion.

He was noted to have low Hematocrit of 35% which fell to a low of 22% with mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count 99000/μL), and normal international normalized ratio is 1.1.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed extensive duodenal varices and follow-up angiography of the portal system visualized abnormal venous anatomy significant for occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein with extensive collateral formation.

The patient was stabilized with seven packed red blood cell transfusions, with initial medical therapy of pantoprazole and octreotide infusions; definite therapy was endoscopic sclerotherapy with injection of 4 mL of 5% ethanolamine into the varices with resolution of active bleeding.

The patient had a history of remote crush abdominal injury and small bowel resection which may have resulted in his anomalous vasculature, thus predisposing him to extrahepatic portal hypertension and the resultant isolated duodenal varices.

Omphalophlebitis is inflammation of the umbilical vein.

A patient medical history indicative of prior intraabdominal pathology such as crush injury should raise suspicion that duodenal varices could be present which allows the endoscopist to adequately prepare for appropriate therapeutic intervention; in this case sclerotherapy was an effective and long lasting definitive treatment.

This paper addresses an important and poor-investigated area dealing with the endoscopic treatment of bleeding from duodenal varices and provides a good review of the literature of the different endoscopic approaches in intrahepatic and extrahepatic portal hypertension causing massive duodenal variceal bleeding. The authors provide a very detailed report of their experience in treating patients affected by this clinical condition and discuss the endoscopic approach and the clinical outcome.

| 1. | Hashizume M, Tanoue K, Ohta M, Ueno K, Sugimachi K, Kashiwagi M, Sueishi K. Vascular anatomy of duodenal varices: angiographic and histopathological assessments. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1942-1945. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kakutani H, Sasaki S, Ueda K, Takakura K, Sumiyama K, Imazu H, Hino S, Kawamura M, Tajiri H. Is it safe to perform endoscopic band ligation for the duodenum A pilot study in ex vivo porcine models. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2013;22:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Linder S, Wiechel KL. Duodenal varicose veins. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gunnerson AC, Diehl DL, Nguyen VN, Shellenberger MJ, Blansfield J. Endoscopic duodenal variceal ligation: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:900-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Itzchak Y, Glickman MG. Duodenal varices in extrahepatic portal obstruction. Radiology. 1977;124:619-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bommana V, Shah P, Kometa M, Narwal R, Sharma P. A Case of Isolated Duodenal Varices Secondary to Chronic Pancreatitis with Review of Literature. Gastroenterology Research. 2010;3:281-286. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tanaka T, Kato K, Taniguchi T, Takagi D, Takeyama N, Kitazawa Y. A case of ruptured duodenal varices and review of the literature. Jpn J Surg. 1988;18:595-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sauerbruch T, Weinzierl M, Dietrich HP, Antes G, Eisenburg J, Paumgartner G. Sclerotherapy of a bleeding duodenal varix. Endoscopy. 1982;14:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haruta I, Isobe Y, Ueno E, Toda J, Mitsunaga A, Noguchi S, Kimura T, Shimizu K, Yamauchi K, Hayashi N. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO), a promising nonsurgical therapy for ectopic varices: a case report of successful treatment of duodenal varices by BRTO. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2594-2597. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bosch A, Marsano L, Varilek GW. Successful obliteration of duodenal varices after endoscopic ligation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1809-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goetz M, Rahman FK, Galle PR, Kiesslich R. Duodenal and rectal varices as a source of severe upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cottam DR, Clark R, Hayn E, Shaftan G. Duodenal varices: a novel treatment and literature review. Am Surg. 2002;68:407-409. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Osaka N, Amatsu T, Masaki H, Ando M, Tanaka M, Imaki M, Morita K, Oshiba S. A Case of ruptured duodenal varix due to vascular malformation. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 1987;29:134. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Tsuji H, Okano H, Fujino H, Satoh T, Kodama T, Takino T, Yoshimura N, Aikawa I, Oka T, Tsuchihashi Y. A case of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for a bleeding duodenal varix. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1989;24:60-64. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sans M, Llach J, Bordas JM, Andreu V, Reverter JC, Bosch J, Mondelo F, Salmerón JM, Mas A, Terés J. Thrombin and ethanolamine injection therapy in arresting uncontrolled bleeding from duodenal varices. Endoscopy. 1996;28:403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kao WY, Wu WC, Chen PH, Chiou YY. Duodenal variceal bleeding caused by chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:922-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Luman W, Hudson N, Choudari CP, Eastwood MA, Palmer KR. Distal biliary stricture as a complication of sclerosant injection for bleeding duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1994;35:1665-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu Y, Yang J, Wang J, Chai G, Sun G, Wang Z, Yang Y. Clinical characteristics and endoscopic treatment with cyanoacrylate injection in patients with duodenal varices. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1012-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Benedetti G, Sablich R, Lacchin T, Masiero A. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding duodenal varices by bucrylate injection. Endoscopy. 1993;25:432-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kakutani H, Sasaki S, Ueda K, Takakura K, Sumiyama K, Imazu H, Hino S, Kawamura M, Tajiri H. Is it safe to perform endoscopic band ligation for the duodenum A pilot study in ex vivo porcine models. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2013;22:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Abdel-Salam OME, Caviglia R, Dumitrascu DL

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D