Published online Dec 5, 2025. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.109177

Revised: July 1, 2025

Accepted: November 5, 2025

Published online: December 5, 2025

Processing time: 218 Days and 7 Hours

With emerging scientific breakthroughs, it has been established that gut micro

Core Tip: Postbiotics, bioactive compounds produced by beneficial microbes, have emerged as promising therapeutic agents for liver diseases linked to gut microbiome dysbiosis. They offer anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant benefits, aiding in conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Limited research underscores the need for extensive studies to unravel their classification, mechanisms, and potential in combating microbial and metabolic disorders.

- Citation: Jeyaraman N, Jeyaraman M, Mariappan T, Nallakumarasamy A, Subramanian P, T P, Vetrivel VN. Harnessing postbiotics for liver health: Emerging perspectives. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2025; 16(4): 109177

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v16/i4/109177.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v16.i4.109177

Postbiotics are garnering significant attention in the nutritional research area due to their several advantages and therapeutic potential over prebiotics and postbiotics. International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics define postbiotics as “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit to the host”[1]. It encompasses a broad range of metabolites and components used such as inanimate cells and their components such as cell walls, membranes, exopolysaccharides (EPSs), anchoring protein with or without metabolites/end products such as proteins, enzymes, bacteriocins, peptides etc.[2]. The substances released from microbes denote the metabolic products produced during the life or after the death of the microbe whereas inanimate microbes are non-viable microbial cells or fragments of their physical structure which retains biologic activity. The diverse array of terminologies used to identify postbiotics in literature are proteobiotics, pharmabiotics, metabiotics, paraprobiotics, non-viable probiotics, inactivated probiotics, ghost probiotics or tyndallized probiotics. The liver and gut are interlinked through the portal circulation hence forming the gut-liver axis[3]. Gut dysbiosis has been associated with a breach in the intestinal barrier and translocation of bacterial endotoxins leading to immune dysregulation which forms the basis for various metabolic derangements[4]. In various pre-clinical and clinical trials postbiotics are effective in enhancing intestinal tight junctions, immunomodulation and altering gut microbiome either directly or indirectly. This review highlights the role of postbiotics in serving as a possible potent treatment modality in liver health.

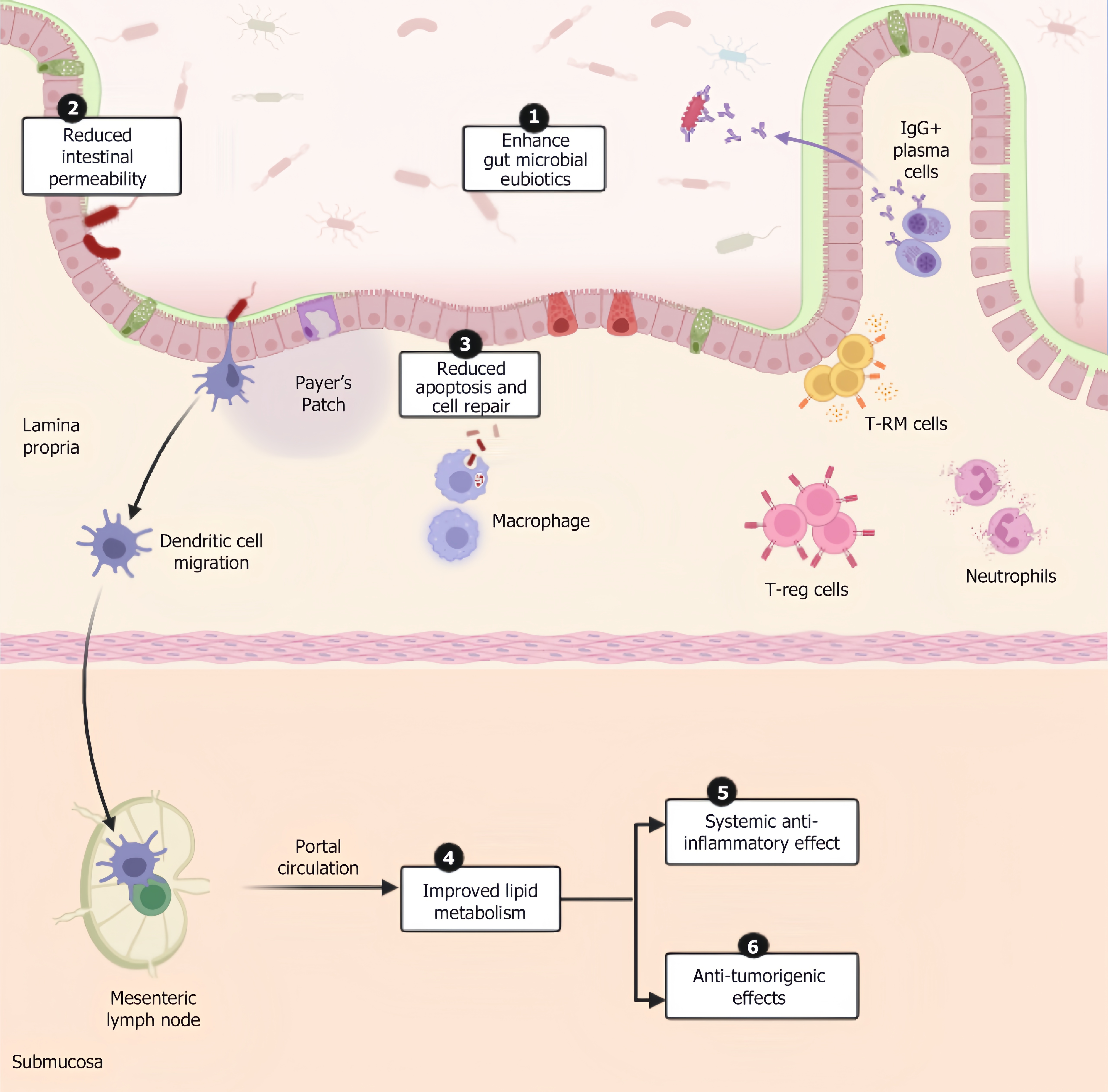

Among the various beneficial interactions proposed by various studies, the primary mechanisms which play a valuable role in liver therapeutics are mentioned below (Figure 1).

It’s established directly by the action of bacteriocins, known for their antibacterial properties derived from the super

Injury by toxins from pathogenic organisms is usually prevented by the intestinal epithelial barrier comprising a mucous layer, gut epithelial layer and antimicrobial enzymes and peptides. Thus, breach in the barrier as a result of dysbiosis is rectified by stimulating mucosal excretion. In vivo, studies show that the supernatant of Lactobacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) consists of 2 components (HM0539 and p40), which promote mucin production via the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway through epithelial cells, which decreases intestinal permeability[8]. Similarly, Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) EPS stimulates mucin production by goblet cells and upregulate zonula occludens-1 and occludin through mitogen-activated protein kinases and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathways which ameliorates the permeability of the intestinal wall[9]. Generoso et al[10] demonstrated the role of cell wall structures of Saccharomyces boulardii in preserving intestinal permeability while limiting microbial product translocation. Similarly, postbiotic products of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus acidophilus (L. acidophilus) inhibited breach in intestinal barrier by toxins from pathogenic bacteria by activating nitric oxide synthase (NOS), thereby counteracting the toxigenic effects[10].

Postbiotics derived from Lactobacillus have been proven to enhance the healing of the lining epithelium of the gut and support tissue repair by increasing the expression of Cdc42 and Pak1[11].

Microbe-derived SCFAs like propionate improve lipid metabolism via activation of GPR41 which leads to inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, resulting in reduced tumorigenesis and increased apoptosis and GRP43-mediated signalling causes downregulation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) leading to decreased transcription of pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic genes like tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and interleukin (IL)-6. Activation of AMP kinase pathway (AMPK) causes mTORC1 suppression leading to inhibition of anabolic metabolism. They also enhance insulin sensitivity through increase in glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) secretion. Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila) supplementation has been shown to decrease markers of liver disease by reducing total cholesterol, serum lipopolysaccharides (LPS), fat mass, and insulin resistance in obese people[12]. In mice studies, downregulation of perilipin 2-associated protein in white and brown adipose tissue in mice was observed[13]. SCFAs like butyrate were found to increase glutathione levels in the colon, which reduced damage exerted by oxidative free radicals. Acetate has been shown to decrease lipolysis and increase fatty acid oxidation and energy expenditure. SCFAs have been shown to have anti-obesity effects on satiety, satiation, and energy expenditure by upregulating GLP-1 and PYY levels[14]. Such effects are produced through muramyl dipeptide which is a bacterial cell wall component by regulating GLP-1 secretion and insulin sensitivity[15]. In vitro studies of Bhat and Bajaj[16] have shown the cholesterol-lowering effects of EPSs of Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) M7. EPSs of Bacillus sp., Lactobacillus delbrueckii, L. plantarum exhibits anti-oxidant effects through AMPK/PI3K/Akt and NF-kB pathway and scavenges reactive oxygen species[17]. They exhibit anti-obesogenic effects through regulation of steroid response element binding protein-1C which is downregulated by farsenoid-X receptor (FXR) activation by postbiotic metabolites (indole derivatives), stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1, acetyl CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase and reduces very low-density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels[18]. Vitamins obtained from Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium adolescents, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis exhibit anti-oxidant effects through superoxide dismutase and catalase enzyme activity reduction and decrease in superoxide radicals production[19]. Although SCFAs have demonstrated hepatoprotective effects in general models of MASLD, studies that specifically evaluate their efficacy across histologically or metabolically distinct MASLD subtypes are currently lacking and represent a vital area for future research.

Postbiotic components are known to reduce oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines through various mech

The protective component valeric acid, obtained from SCFAs of L. acidophilus exhibits anti-tumourigenic effects in vivo and in vitro by binding to GRP41/43 on liver cells to inactivate oncogenic pathways. Transcriptomic analysis done by Lau et al[22] and team revealed that several genes related to Rho GTPase pathway and cell cycle-RHOA, RAC1, ROCK1 and BUB1, CDC25C, CDC45, CDK1 had shown to be significantly downregulated in mouse NAFLD-HCC cells and liver cells after treatment with valeric acid. EPS-R1 increased cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 and programmed death receptor-1 monoclonal antibodies against cysteine-cysteine motif chemokine ligand 20-exhibiting tumours by boosting antigen presentation and T-cell activation by stimulating dendritic cells and promoting major histocompatibility complex expression leading to increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells and as a result when such antibodies are administered, the immune system is already primed to exhibit a robust response in mice models[23]. Targeted supplementation with specific postbiotic types (e.g., valeric acid for MASLD-HCC) holds greater promise when guided by metagenomic and metabolomic profiling[22,24,25].

Angiotensin convertase enzyme 2 is expressed in 60% of cholangiocytes and 3% of hepatocytes. The virus enters through these receptors and induce IL-6 and TNF-alpha mediated pro-inflammatory state, contributing to hepatocellular damage. In this study the anti-oxidant, anti-viral, and anti-inflammatory effects of various phytochemiucals were studied. Curcumin, a polyphenol, was found to possess anti-inflammatory effects through NK-κB inhibition thereby improving liver function and alleviation of liver inflammation in individuals with MASLD. Other phytochemicals like quercetin and resveratrol have anti-viral effects. Quercetin, apigenin, curcumin, resveratrol and carotenoids are known to have anti-oxidant effects which mitigates the damage induced by free radicals[26].

Postbiotics are obtained from microorganisms in food or fermented foods. Essentially prebiotics from dietary sources such as fibres and oligosaccharides serve as substrates for gut microbes, which in turn metabolize them to produce bioactive compounds known as postbiotics which are either substances released from microbes or the inanimate microbes themselves, comprising of cell wall constituents (peptidoglycans, teichoic acids), cell-free supernatants, bacteriocins, SCFAs, branched-chain fatty acids, polysaccharides, vitamins etc.[27]. Current innovations aim at isolating these postbiotics from supernatants and studying the effects of each component individually through pre-clinical trials. Other methods perform lysis of bacterial cells through thermal, enzymatic, chemical, sonification, hyperbaric, and solvent extraction. Several concentrating and purifying techniques are used to perform qualitative and quantitative analysis of the extracted metabolites. The extracted solutions underwent centrifugation, dialysis, lyophilization, and column purification to isolate postbiotics from bacterial cells. The obtained postbiotics undergo characterization as cell wall fragments, intracellular metabolites, and secreted metabolites by appropriate methods such as chromatography, spectrophotometry, and spectroscopy[28]. Such postbiotics obtained after undergoing treatment introduce several other intracellular substances and cell wall derived products, which when combined with the existing pool of postbiotics several new beneficial therapeutic functions can be obtained[7]. The effects of postbiotics on various liver disorders are tabulated in Table 1[8,16,29-67].

| Ref. | Type of the study | Postbiotic involved | Mechanisms and outcomes |

| Inactivated bacteria | |||

| Depommier et al[29] | In vivo in mice | A. muciniphila | Increased energy expenditure, obesity |

| Depommier et al[30] | Clinical trial | A. muciniphila | Improves obesity with insulin resistance |

| Andresen et al[31] | Clinical trial | Bifidobacterium bifidum | Improves symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome |

| Shin et al[32] | In vivo: Male rats | B. longum SPM1207 | Decreases total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| Martorell et al[33] | In vivo: Caenorhabditis elegans. In vitro: Human colonic epithelial cells | B. longum CECT 7347 | Alleviate gut barrier disruption by its anti-inflammatory properties |

| Nakamura et al[34] | In vivo: Male c57BL/6n mice | Lactobacillus amylovorus CP 1563 | Treatment and prevention of dyslipidemia |

| Aiba et al[35] | In vitro | Lactobacillus johnsonii | Inhibits colonization of Helicobacter pylori |

| Miyauchi et al[36] | In vitro: Intestinal epithelial cells | L. rhamnosus OLL 2838 | Intestinal barrier activity |

| Bacterial lysates | |||

| Jensen et al[37] | In vivo in mice | Methylcoccus capsulatus | Enhance glucose regulation and decrease body and liver fat, MASLD |

| Mack et al[38] | Clinical trial | Escherichia coli DSM 17252 and Enterococcus faecalis DSM 16440 | Improves diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by ameliorating endotoxin translocation and indirectly prevents the gut-liver translocation |

| Osman et al[39] | In vivo: Male rats | L. paracasei | Reduced lipids and triglycerides accumulation and significant reduction in elevated liver enzymes |

| Wang et al[40] | In vivo: Male mice | L. rhamnosus GG | Alcoholic liver disease prevention |

| Compare et al[41] | Ex vivo: Organ culture model | Lactobacillus casei DG | Alleviate inflammatory effects in intestinal mucosa |

| Gao et al[8] | In vitro: Intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2). In vivo: Mice | L. rhamnosus GG | Ameliorates intestinal barrier dysfunction and protects intestinal epithelium thereby preventing translocation to liver |

| Mi et al[42] | In vitro: RAW264.7 cells. In vivo: Male mice. Ex vivo: Mouse splenocytes | Bacillus velezensis Kh2-2 | Stimulate innate and adaptive immunity and regulate gut dysbiosis. Increase IL-2 secretion and inhibit IL-10 secretion in ex vivo model |

| Dinić et al[43] | In vitro study-HepG2 human hepatocyte cell line | Lactobacillus fermentum BGHV 110 | Stimulation of PTEN-induced putative kinase 1-dependent autophagy in HepG2 cells and mitigation of hepatotoxicity induced by acetaminophen |

| Bacterial vesicles | |||

| Hao et al[44] | In vivo mice | L. plantarum | Body weight loss and mitigate bleeding and colon shortening |

| Bacterial metabolites | |||

| He et al[45] | In vivo mice and in vitro in tumour cells | Short chain fatty acid-butyrate | Improve CD8+ T cell immunity providing anti-tumour effects |

| Suez and Elinav[46] | In vivo in mice | Phytate and inositol triphosphate | Enhance gut epithelial proliferation and injury recovery |

| Ma et al[47] | In vivo in mice | Indole | Activate PFKFB3 expression and inhibit macrophage activation, MASLD |

| Li et al[48] | In vivo in mice and in vitro bacterial culture | Isoallolithocolic acid | Regulation of Treg cells by bile acid metabolites |

| Dahech et al[49] | In vivo in male Wistar rats | Polysaccharides of Bacillus licheniformis | Reduce glucose levels and hepatic and renal toxicity measured through thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| Ghoneim et al[50] | In vivo in male Sprague-Dawlwy rats | Polysaccharides of Bacillus subtilis sp | Reduce glucose levels and prevent complications of diabetes |

| Amaretti et al[51] | In vitro | The mixture of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, and Streptococcus thermophilus | Anti-oxidant properties |

| Segawa et al[52] | In vitro | Polyphosphates of Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 | Mediates epithelial barrier |

| Chen et al[53] | In vivo: Mice | SCFA of Clostridium butyricum sp | Regulate gut microbiome composition |

| Ticho et al[54] | In vivo in mice | Products of commensals after digestion of bile acids by Bacteroides, Eubacterium and Clostridium | Modulation via farsenoid-X receptor and GPCR5 which regulates lipid and lipoprotein metabolism |

| Rajakovich and Balskus[55] | In vivo | Products of Lactocilli, Bifidobacterium synthesize vitamins A, C, and B9 | Enhance mucous secretion by epithelial cells and maintain the integrity of goblet cells |

| Noronha et al[56] | In vivo | Products of Bacteroides and thetaiotaomicron enhance angiogenin 4 expression | Angiogenin 4 has antibacterial activities |

| Other components | |||

| Balaguer et al[57] | In vivo in Caenorhabditis elegans | Lipoteichoic acid of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis CECT 8145 | Anti-obesity as it reduces fat in nematodes |

| Schiavi et al[58] | In vitro in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells | EPS of B. longum W11 | Regulates cytokine secretion and nuclear factor kappa B activation through anti-inflammatory properties |

| Bhat and Bajaj[16] | In vitro | EPS of L. paracasei M7 | Decrease total cholesterol, immunomodulation |

| Kim et al[59] | In vitro: Human monocyte cells (THP-1) | Lipoteichoic acid of L. plantarum | Inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling in THP-1 cells |

| Matsuguchi et al[60] | In vitro in RAW264.7 cells of mouse | Lipoteichoic acid of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, L. plantarum | Attenuate LPS-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production |

| Wang et al[61] | In vivo in male mice | Lipoteichoic acid of L. paracasei D3-5 | Stimulate mucin production through its anti-inflammatory role and reduces systemic endotoxemia |

| Rahbar Saadat et al[62] | In vivo in mice | EPS of L. paracasei | Exhibits cholesterol lowering and metabolic regulation properties |

| Kareem et al[63] | In vitro | Cell free supernatant of L. plantarum RG11, RG14, RI11, UL4, TL1, RS5 | Antimicrobial activity |

| Bali et al[64] | In vitro | Cell-free supernatant Bifidobacterium sp | Bacteriocin production against pathogenic organisms |

| Foo et al[65] | In vivo in mice | L. plantarum I-UL4, Bacteriocin | Significant reduction in total cholesterol concentrations in comparison to controls |

| Riaz Rajoka et al[66] | In vitro | Cell-free supernatant of L. rhamnosus SHA111, SHA112, and SHA113 | Induces apoptosis by up-regulation of BAD, BAX, Caspase-3, Caspase-8, Caspase-9, and down regulation of BCL-2 genes |

| Qi et al[67] | In vitro in RAW264.7 cells of mouse macrophages | Cell wall components of L. rhamnosus GG | Components protect macrophages from LPS-induced inflammation |

Fogacci et al[68] assessed the impact of butyrate-based formula on individuals with hepatic steatosis and metabolic syndrome. This supplementation was found to have improved fatty liver index, hepatic steatosis index, gamma-glutamyl transferase and lipid profiles[68]. A clinical trial assessing the impact of A. muciniphila supplementation in obese individuals with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and elevated liver enzymes resulted in improved insulin sensitivity and decreased liver enzyme levels (Depommier et al[30]). However, in these studies the smaller sample size and limited duration of studies warrant for more large-scale and long-term clinical trials to translate these results into practical benefits. While studies assessing postbiotic supplementation in liver diseases are limited, it holds great potential to act as either an adjunct or a standalone therapy for liver diseases linked to gut dysbiosis[30].

Postbiotics are resistant to digestive enzymes and are absorbed directly (SCFAs) or remain active at the site of administration (bacteriocins, cell wall components) without requiring further microbial fermentation or colonization unlike probiotics. Thus, postbiotics act rapidly after administration and prebiotics require time for fermentation and metabolite conversion. Postbiotics bypass the need for fermentation for gut bacteria, making them effective even in dysbiotic guts as seen in liver disorders[11,69]. Prebiotics require a functioning microbiome to yield therapeutic metabolites. In altered gut environment it may fail to reproduce such effects. Postbiotics are stable compounds with longer shelf life due to stability across wide range of temperature and pH and don’t necessitate appropriate storage precautions. They don’t require cold storage or encapsulation like prebiotics. Postbiotics can be precisely quantified, characterized and dosed whereas the effects of prebiotics are variable. Thereby, postbiotics can be precisely customized for individuals. For example, butyrate-based therapy can be administered for individuals deficient in SCFAs. Personalization becomes difficult with prebiotics as they produce diverse variable metabolites. Probiotics, being non-viable eliminate the risk of bacterial translocation causing bacteremia or sepsis as seen in some probiotics in immunocompromised hosts. They don’t interfere with the antibiotics administered as they lack transmissible genetic material[27,70,71]. Their actions are similar to that of probiotics thus the risk of live microorganisms administered as probiotics to patients with compromised intestinal barrier and immune system can be avoided. Various possible properties of postbiotics[72-76] are noted like anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, anti-obesogenic, anti-carcinogenic, hypocholesterolemic, immunomodulatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-proliferative activities[77]. Postbiotics exhibit such pleiotropic effects that span several organ systems through their above effects. These are difficult to achieve with prebiotics alone without depending the host microbiota status. The risk of carrying antibiotic-resistant genes in probiotic strains is minimized through the use of postbiotics[69]. With respect to regulatory safety, postbiotics are easier to regulate than prebiotics as postbiotics are bioactive molecules with no live organisms unlike prebiotics. There are several possible delivery formats for postbiotics as discussed below but it’s limited with prebiotics owing to their need for colonic ferementation. They have a role in treating a wide array of diseases which lacks definitive therapeutics.

Patients with MASLD have shown in heterogeneity in clinical stages and histological diversity where certain population shows benign liver disease while others show extensive fibrosis and liver failure. This has been attributed to the indi

Oral route has been established as the superior mode of delivery due to its several advantages such as better adherence to treatment, conveniency for frequent administration, safety, low cost and better local and systemic effects where the latter is achieved through lymphatic absorption of postbiotics whose lipophilic nature enables them to bypass first pass meta

The pH: The natural pH of the stomach is at 1-4 and that of small and large intestine are between 6 and 7.4. This natural pH should be kept in mind while designing the targeted delivery mechanisms. Thus, to achieve targeted delivery at the colon, methacrylic based polymers also known as enTRinsic capsules have shown to demonstrate resistance to gastric enzymes in the stomach and rapid release of postbiotics (SCFAs based) in intestine[86]. Puccetti et al[87] formulated a new local delivery technique using indole-3-aldehyde loaded gastro resistant spray dried microparticle for postbiotics to reach the targeted area of release. Innovations in pH-dependent delivery systems include methacrylic-acid based polymers (Eudragit), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate, cellulose acetate phthalate, Colopulse and enTRinsic capsules[88].

Gut microbiota: They have the potential to ferment prebiotics naturally through the use of their enzymes such as polysaccharides and azo-reductases. Thus, polysaccharide and azo coated preparations can be used for targeted delivery[89]. Recently double layered coating systems are used where the core layer has a chitosan based polymeric substance with citric acid and an outer enteric layer. This prevents release of postbiotics in stomach and intestine and on reaching the colon the layers dissolve under the action of chitosonase released by gut microbiota[90]. In patients with altered gut microbiome as a result of diarrhea or any inflammatory conditions, probiotics are co-administered to maintain eubiosis and targeted release of postbiotics. Current technologies using microbiota triggered delivery include COLAL, Phloral, COlon-targeted Delivery System, TARGIT etc.[91].

Time: The time of delivery has been correlated with the gastrointestinal transit times. But the high variability of transit times among individuals has hindered this concept. Thus, mesalamine based preparations (multimatrix) whose release are independent of time are utilized where they achieve maximum concentration in the colon[92]. Widely studied technologies using time dependent delivery include ChronoCap, Pulsnicap, Multimarix[93].

Osmotic pressure: Osmotic pressure-controlled delivery utilizes a double layered capsule where the outer enteric capsule made of gelatin is dissolved in the intestine and the inner core consists of push-pull osmotic units. The inner layer of enteric layer consists of a semi-permeable membrane which encompasses the osmotic and therapeutic unit. On dissolving the osmotic unit swells up leading to release of the therapeutic unit through the orifice[94]. These systems maintain consistent postbiotic release, improving systemic absorption of hepatoprotective metabolites and minimizing variability in gut fermentation times which is key in cirrhosis or MASLD patients with altered microbiota.

Nanoparticle delivery system: Among the various nanoparticle delivery systems, lipid or polysaccharide-based liposomes have proved to be effective to tide over inflammatory or neoplastic conditions. These coated liposomes are used to deliver several postbiotics such as vitamins and bacteriocins. Such delivery mechanisms prevent interaction of those nanoparticles with food and proteases of digestive tract. Hydrogels also serve as an effective nanoparticle carrying system as explained below. Promising potential of such delivery systems can be extrapolated to a large scale through more clinical trials. Some extensively studied systems include chitosan, poly (lactic-co glycolic acid), mesoporous silica nanoparticles, nanoparticle in microparticle oral delivery system, hydrogel microfibers and liposomes[95]. Such systems are highlighted for their potential to cross intestinal epithelium and enter systemic circulation, allowing targeted hepatic delivery.

Intravenous (IV) route is preferred for widespread systemic release of probiotics[96-98]. It has been discussed on lines on bypassing first pass metabolism, providing systemic hepatic access. However, IV postbiotic therapy for liver disease remains largely theoretical with no established large scale clinical evidence or regulatory approval. Among all of the above proposed modes, transport of postbiotics as nanoparticles are shown to be effective for in vivo infusion with persistent release. Such particles are transported through pulsatile delivery mechanisms to maintain a steady state plasma concentration for the desired duration. Such infusions have the benefit of limiting multiple doses, leading to improved patient’s compliance[99].

Hydrogels also serve as an effective alternative owing to their one-of-a-kind properties, such as a three-dimensional polymeric structure with numerous micropores which enable them to disperse to their surroundings. They are also hydrophilic and thermo-responsive which enables them to change their size inside a capsule. Such heat-sensitive properties enable them to function as a flip switch by expansion and contraction[100].

However, IV administration has its own set of disadvantages such as infections through contaminated needles, improper patient adherence and lack of local effects. The major regulatory barriers include manufacturing purity, immunogenicity and lack of human dosing data.

By linking the above discussed delivery mechanisms to gut-liver signalling and hepatic pathophysiology, the translational potential of postbiotics could be enhanced.

Postbiotics lack standardized definitions and criteria which makes it difficult to compare researchers and products. Thus, postbiotics currently fall into a regulatory gray zone with no dedicated regulatory category under Food and Drug Administration or World Health Organization frameworks. The variability in strain identity, culture medium, growth conditions, etc., poses a major challenge in ensuring batch-to-batch consistency in bioactive content. The industrial processing of postbiotics from fermentation to inactivation and drying affects the yield and activity of the contents. Postbiotics cannot proliferate and thus require frequent dosing and non-adherence leads to diminished benefits[101]. As most human studies use food-based doses with no recording of dose-response data, the risk of overdosing or under

The gut microbiome is considered as a virtual organ which has complex interlinked pathways with various metabolic processes. Postbiotics are an appealing therapeutic option due to their diverse pleiotropic efforts on several interlinked metabolic pathways and their beneficial properties. The active components of postbiotics with properties such as anti-inflammatory, anti-obesogenic, anti-oxidant, hypocholesterolemic and immunomodulation have diverse applications in serving as a treatment option for liver diseases as summarized above. Further research aimed at translating results in animal models to humans is required to analyze the beneficial and hazardous side effects before applying it clinically. This review calls for large scale human clinical trials, dose-response studies and development of targeted delivery systems while addressing regulatory challenges, safety profiling and translational gaps. With emerging cohorts and cross-sectional studies, we have progressed from learning correlations to understanding associations between gut microbiome and liver diseases.

| 1. | Salminen S, Collado MC, Endo A, Hill C, Lebeer S, Quigley EMM, Sanders ME, Shamir R, Swann JR, Szajewska H, Vinderola G. Reply to: Postbiotics - when simplification fails to clarify. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:827-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Asefa Z, Belay A, Welelaw E, Haile M. Postbiotics and their biotherapeutic potential for chronic disease and their feature perspective: A review. Front Microbiomes. 2025;4:1489339. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Ohtani N, Kawada N. Role of the Gut-Liver Axis in Liver Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Cancer: A Special Focus on the Gut Microbiota Relationship. Hepatol Commun. 2019;3:456-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Muñoz L, Borrero MJ, Úbeda M, Conde E, Del Campo R, Rodríguez-Serrano M, Lario M, Sánchez-Díaz AM, Pastor O, Díaz D, García-Bermejo L, Monserrat J, Álvarez-Mon M, Albillos A. Intestinal Immune Dysregulation Driven by Dysbiosis Promotes Barrier Disruption and Bacterial Translocation in Rats With Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2019;70:925-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Thakur R, Kaur S. Use of postbiotics and parabiotics from lactobacilli in the treatment of infectious diarrhea. Microb Pathog. 2025;204:107580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mu Q, Tavella VJ, Luo XM. Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in Human Health and Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gurunathan S, Thangaraj P, Kim JH. Postbiotics: Functional Food Materials and Therapeutic Agents for Cancer, Diabetes, and Inflammatory Diseases. Foods. 2023;13:89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Gao J, Li Y, Wan Y, Hu T, Liu L, Yang S, Gong Z, Zeng Q, Wei Y, Yang W, Zeng Z, He X, Huang SH, Cao H. A Novel Postbiotic From Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG With a Beneficial Effect on Intestinal Barrier Function. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Song D, Wang X, Ma Y, Liu NN, Wang H. Beneficial insights into postbiotics against colorectal cancer. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1111872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Generoso SV, Viana ML, Santos RG, Arantes RM, Martins FS, Nicoli JR, Machado JA, Correia MI, Cardoso VN. Protection against increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation induced by intestinal obstruction in mice treated with viable and heat-killed Saccharomyces boulardii. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liang B, Xing D. The Current and Future Perspectives of Postbiotics. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2023;15:1626-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pellegrino A, Coppola G, Santopaolo F, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR. Role of Akkermansia in Human Diseases: From Causation to Therapeutic Properties. Nutrients. 2023;15:1815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Libby AE, Bales ES, Monks J, Orlicky DJ, McManaman JL. Perilipin-2 deletion promotes carbohydrate-mediated browning of white adipose tissue at ambient temperature. J Lipid Res. 2018;59:1482-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shen Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Yin B, Ye B, Zhou Y. Advances in the role and mechanism of lactic acid bacteria in treating obesity. Food Bioeng. 2022;1:101-115. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Williams L, Alshehri A, Robichaud B, Cudmore A, Gagnon J. The Role of the Bacterial Muramyl Dipeptide in the Regulation of GLP-1 and Glycemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bhat B, Bajaj BK. Hypocholesterolemic potential and bioactivity spectrum of an exopolysaccharide from a probiotic isolate Lactobacillus paracasei M7. Bioact Carbohydr Dietary Fibre. 2019;19:100191. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Angelin J, Kavitha M. Exopolysaccharides from probiotic bacteria and their health potential. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;162:853-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu X, So JS, Park JG, Lee AH. Transcriptional control of hepatic lipid metabolism by SREBP and ChREBP. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:301-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Averina OV, Poluektova EU, Marsova MV, Danilenko VN. Biomarkers and Utility of the Antioxidant Potential of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria as Representatives of the Human Gut Microbiota. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rezaie N, Aghamohammad S, Haj Agha Gholizadeh Khiavi E, Khatami S, Sohrabi A, Rohani M. The comparative anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of postbiotics and probiotics through Nrf-2 and NF-kB pathways in DSS-induced colitis model. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mazziotta C, Tognon M, Martini F, Torreggiani E, Rotondo JC. Probiotics Mechanism of Action on Immune Cells and Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Cells. 2023;12:184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 144.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lau HC, Zhang X, Ji F, Lin Y, Liang W, Li Q, Chen D, Fong W, Kang X, Liu W, Chu ES, Ng QW, Yu J. Lactobacillus acidophilus suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma through producing valeric acid. EBioMedicine. 2024;100:104952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kawanabe-Matsuda H, Takeda K, Nakamura M, Makino S, Karasaki T, Kakimi K, Nishimukai M, Ohno T, Omi J, Kano K, Uwamizu A, Yagita H, Boneca IG, Eberl G, Aoki J, Smyth MJ, Okumura K. Dietary Lactobacillus-Derived Exopolysaccharide Enhances Immune-Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:1336-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Scott E, De Paepe K, Van de Wiele T. Postbiotics and Their Health Modulatory Biomolecules. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams JB, Aquino-Michaels K, Earley ZM, Benyamin FW, Lei YM, Jabri B, Alegre ML, Chang EB, Gajewski TF. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350:1084-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1979] [Cited by in RCA: 3055] [Article Influence: 277.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Balaji D, Balakrishnan R, Srinivasan D, Subbarayan R, Shrestha R, Srivastava N, Chauhan A. The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Liver Diseases and Potential Phytochemical Treatments. Infect Microb Dis. 2024;6:177-188. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Rafique N, Jan SY, Dar AH, Dash KK, Sarkar A, Shams R, Pandey VK, Khan SA, Amin QA, Hussain SZ. Promising bioactivities of postbiotics: A comprehensive review. J Agric Food Res. 2023;14:100708. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Kumar A, Green KM, Rawat M. A Comprehensive Overview of Postbiotics with a Special Focus on Discovery Techniques and Clinical Applications. Foods. 2024;13:2937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Depommier C, Van Hul M, Everard A, Delzenne NM, De Vos WM, Cani PD. Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila increases whole-body energy expenditure and fecal energy excretion in diet-induced obese mice. Gut Microbes. 2020;11:1231-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Depommier C, Everard A, Druart C, Plovier H, Van Hul M, Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Raes J, Maiter D, Delzenne NM, de Barsy M, Loumaye A, Hermans MP, Thissen JP, de Vos WM, Cani PD. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat Med. 2019;25:1096-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 1579] [Article Influence: 225.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Andresen V, Gschossmann J, Layer P. Heat-inactivated Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 (SYN-HI-001) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:658-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shin HS, Park SY, Lee DK, Kim SA, An HM, Kim JR, Kim MJ, Cha MG, Lee SW, Kim KJ, Lee KO, Ha NJ. Hypocholesterolemic effect of sonication-killed Bifidobacterium longum isolated from healthy adult Koreans in high cholesterol fed rats. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1425-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Martorell P, Alvarez B, Llopis S, Navarro V, Ortiz P, Gonzalez N, Balaguer F, Rojas A, Chenoll E, Ramón D, Tortajada M. Heat-Treated Bifidobacterium longum CECT-7347: A Whole-Cell Postbiotic with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Gut-Barrier Protection Properties. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10:536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nakamura F, Ishida Y, Sawada D, Ashida N, Sugawara T, Sakai M, Goto T, Kawada T, Fujiwara S. Fragmented Lactic Acid Bacterial Cells Activate Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Ameliorate Dyslipidemia in Obese Mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:2549-2559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Aiba Y, Ishikawa H, Tokunaga M, Komatsu Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of non-living, heat-killed form of lactobacilli including Lactobacillus johnsonii No.1088. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017;364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Miyauchi E, Morita H, Tanabe S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus alleviates intestinal barrier dysfunction in part by increasing expression of zonula occludens-1 and myosin light-chain kinase in vivo. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2400-2408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Jensen BAH, Holm JB, Larsen IS, von Burg N, Derer S, Sonne SB, Pærregaard SI, Damgaard MV, Indrelid SA, Rivollier A, Agrinier AL, Sulek K, Arnoldussen YJ, Fjære E, Marette A, Angell IL, Rudi K, Treebak JT, Madsen L, Åkesson CP, Agace W, Sina C, Kleiveland CR, Kristiansen K, Lea TE. Lysates of Methylococcus capsulatus Bath induce a lean-like microbiota, intestinal FoxP3(+)RORγt(+)IL-17(+) Tregs and improve metabolism. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mack I, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Mazurak N, Niesler B, Zimmermann K, Mönnikes H, Enck P. A Nonviable Probiotic in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1039-1047.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Osman A, El-Gazzar N, Almanaa TN, El-Hadary A, Sitohy M. Lipolytic Postbiotic from Lactobacillus paracasei Manages Metabolic Syndrome in Albino Wistar Rats. Molecules. 2021;26:472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wang Y, Liu Y, Sidhu A, Ma Z, McClain C, Feng W. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG culture supernatant ameliorates acute alcohol-induced intestinal permeability and liver injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G32-G41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Compare D, Rocco A, Coccoli P, Angrisani D, Sgamato C, Iovine B, Salvatore U, Nardone G. Lactobacillus casei DG and its postbiotic reduce the inflammatory mucosal response: an ex-vivo organ culture model of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mi XJ, Tran THM, Park HR, Xu XY, Subramaniyam S, Choi HS, Kim J, Koh SC, Kim YJ. Immune-enhancing effects of postbiotic produced by Bacillus velezensis Kh2-2 isolated from Korea Foods. Food Res Int. 2022;152:110911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dinić M, Lukić J, Djokić J, Milenković M, Strahinić I, Golić N, Begović J. Lactobacillus fermentum Postbiotic-induced Autophagy as Potential Approach for Treatment of Acetaminophen Hepatotoxicity. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hao H, Zhang X, Tong L, Liu Q, Liang X, Bu Y, Gong P, Liu T, Zhang L, Xia Y, Ai L, Yi H. Effect of Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Lactobacillus plantarum Q7 on Gut Microbiota and Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Front Immunol. 2021;12:777147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | He Y, Fu L, Li Y, Wang W, Gong M, Zhang J, Dong X, Huang J, Wang Q, Mackay CR, Fu YX, Chen Y, Guo X. Gut microbial metabolites facilitate anticancer therapy efficacy by modulating cytotoxic CD8(+) T cell immunity. Cell Metab. 2021;33:988-1000.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 100.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Suez J, Elinav E. The path towards microbiome-based metabolite treatment. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ma L, Li H, Hu J, Zheng J, Zhou J, Botchlett R, Matthews D, Zeng T, Chen L, Xiao X, Athrey G, Threadgill DW, Li Q, Glaser S, Francis H, Meng F, Li Q, Alpini G, Wu C. Indole Alleviates Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis and Inflammation in a Manner Involving Myeloid Cell 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Biphosphatase 3. Hepatology. 2020;72:1191-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Li W, Hang S, Fang Y, Bae S, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Wang G, McCurry MD, Bae M, Paik D, Franzosa EA, Rastinejad F, Huttenhower C, Yao L, Devlin AS, Huh JR. A bacterial bile acid metabolite modulates T(reg) activity through the nuclear hormone receptor NR4A1. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:1366-1377.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dahech I, Belghith KS, Hamden K, Feki A, Belghith H, Mejdoub H. Antidiabetic activity of levan polysaccharide in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49:742-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ghoneim MAM, Hassan AI, Mahmoud MG, Asker MS. Effect of polysaccharide from Bacillus subtilis sp. on cardiovascular diseases and atherogenic indices in diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Amaretti A, di Nunzio M, Pompei A, Raimondi S, Rossi M, Bordoni A. Antioxidant properties of potentially probiotic bacteria: in vitro and in vivo activities. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:809-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Segawa S, Fujiya M, Konishi H, Ueno N, Kobayashi N, Shigyo T, Kohgo Y. Probiotic-derived polyphosphate enhances the epithelial barrier function and maintains intestinal homeostasis through integrin-p38 MAPK pathway. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Chen D, Jin D, Huang S, Wu J, Xu M, Liu T, Dong W, Liu X, Wang S, Zhong W, Liu Y, Jiang R, Piao M, Wang B, Cao H. Clostridium butyricum, a butyrate-producing probiotic, inhibits intestinal tumor development through modulating Wnt signaling and gut microbiota. Cancer Lett. 2020;469:456-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Ticho AL, Malhotra P, Dudeja PK, Gill RK, Alrefai WA. Intestinal Absorption of Bile Acids in Health and Disease. Compr Physiol. 2019;10:21-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Rajakovich LJ, Balskus EP. Metabolic functions of the human gut microbiota: the role of metalloenzymes. Nat Prod Rep. 2019;36:593-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Noronha A, Modamio J, Jarosz Y, Guerard E, Sompairac N, Preciat G, Daníelsdóttir AD, Krecke M, Merten D, Haraldsdóttir HS, Heinken A, Heirendt L, Magnúsdóttir S, Ravcheev DA, Sahoo S, Gawron P, Friscioni L, Garcia B, Prendergast M, Puente A, Rodrigues M, Roy A, Rouquaya M, Wiltgen L, Žagare A, John E, Krueger M, Kuperstein I, Zinovyev A, Schneider R, Fleming RMT, Thiele I. The Virtual Metabolic Human database: integrating human and gut microbiome metabolism with nutrition and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D614-D624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Balaguer F, Enrique M, Llopis S, Barrena M, Navarro V, Álvarez B, Chenoll E, Ramón D, Tortajada M, Martorell P. Lipoteichoic acid from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BPL1: a novel postbiotic that reduces fat deposition via IGF-1 pathway. Microb Biotechnol. 2022;15:805-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Schiavi E, Gleinser M, Molloy E, Groeger D, Frei R, Ferstl R, Rodriguez-Perez N, Ziegler M, Grant R, Moriarty TF, Plattner S, Healy S, O'Connell Motherway M, Akdis CA, Roper J, Altmann F, van Sinderen D, O'Mahony L. The Surface-Associated Exopolysaccharide of Bifidobacterium longum 35624 Plays an Essential Role in Dampening Host Proinflammatory Responses and Repressing Local TH17 Responses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:7185-7196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kim HG, Lee SY, Kim NR, Lee HY, Ko MY, Jung BJ, Kim CM, Lee JM, Park JH, Han SH, Chung DK. Lactobacillus plantarum lipoteichoic acid down-regulated Shigella flexneri peptidoglycan-induced inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:382-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Matsuguchi T, Takagi A, Matsuzaki T, Nagaoka M, Ishikawa K, Yokokura T, Yoshikai Y. Lipoteichoic acids from Lactobacillus strains elicit strong tumor necrosis factor alpha-inducing activities in macrophages through Toll-like receptor 2. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang S, Ahmadi S, Nagpal R, Jain S, Mishra SP, Kavanagh K, Zhu X, Wang Z, McClain DA, Kritchevsky SB, Kitzman DW, Yadav H. Lipoteichoic acid from the cell wall of a heat killed Lactobacillus paracasei D3-5 ameliorates aging-related leaky gut, inflammation and improves physical and cognitive functions: from C. elegans to mice. Geroscience. 2020;42:333-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Rahbar Saadat Y, Yari Khosroushahi A, Pourghassem Gargari B. A comprehensive review of anticancer, immunomodulatory and health beneficial effects of the lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;217:79-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kareem KY, Hooi Ling F, Teck Chwen L, May Foong O, Anjas Asmara S. Inhibitory activity of postbiotic produced by strains of Lactobacillus plantarum using reconstituted media supplemented with inulin. Gut Pathog. 2014;6:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bali V, Panesar PS, Bera MB. Trends in utilization of agro-industrial byproducts for production of bacteriocins and their biopreservative applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2016;36:204-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Foo HF, Loh TC, Lai PW, Lim YZ, Kufli CN, Rusul G. Effects of Adding Lactobacillus plantarum I-UL4 Metabolites in Drinking Water of Rats. Pakistan J of Nutrition. 2003;2:283-288. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Riaz Rajoka MS, Zhao H, Mehwish HM, Li N, Lu Y, Lian Z, Shao D, Jin M, Li Q, Zhao L, Shi J. Anti-tumor potential of cell free culture supernatant of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains isolated from human breast milk. Food Res Int. 2019;123:286-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Qi SR, Cui YJ, Liu JX, Luo X, Wang HF. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG components, SLP, gDNA and CpG, exert protective effects on mouse macrophages upon lipopolysaccharide challenge. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2020;70:118-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Fogacci F, Giovannini M, Di Micoli V, Grandi E, Borghi C, Cicero AFG. Effect of Supplementation of a Butyrate-Based Formula in Individuals with Liver Steatosis and Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2024;16:2454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Bourebaba Y, Marycz K, Mularczyk M, Bourebaba L. Postbiotics as potential new therapeutic agents for metabolic disorders management. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Prajapati N, Patel J, Singh S, Yadav VK, Joshi C, Patani A, Prajapati D, Sahoo DK, Patel A. Postbiotic production: harnessing the power of microbial metabolites for health applications. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1306192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Vinderola G, Sanders ME, Salminen S, Szajewska H. Postbiotics: The concept and their use in healthy populations. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1002213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Hijová E. Postbiotics as Metabolites and Their Biotherapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:5441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Nataraj BH, Ali SA, Behare PV, Yadav H. Postbiotics-parabiotics: the new horizons in microbial biotherapy and functional foods. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 60.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Żółkiewicz J, Marzec A, Ruszczyński M, Feleszko W. Postbiotics-A Step Beyond Pre- and Probiotics. Nutrients. 2020;12:2189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Tsilingiri K, Rescigno M. Postbiotics: what else? Benef Microbes. 2013;4:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Anhê FF, Jensen BAH, Perazza LR, Tchernof A, Schertzer JD, Marette A. Bacterial Postbiotics as Promising Tools to Mitigate Cardiometabolic Diseases. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2021;10:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Wegh CAM, Geerlings SY, Knol J, Roeselers G, Belzer C. Postbiotics and Their Potential Applications in Early Life Nutrition and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 969] [Cited by in RCA: 2283] [Article Influence: 326.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 79. | Hasan N, Yang H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 68.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 80. | Parizadeh M, Arrieta MC. The global human gut microbiome: genes, lifestyles, and diet. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29:789-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, Zhu D, Koya JB, Wei L, Li J, Chen ZS. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 1833] [Article Influence: 458.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 82. | Afzaal M, Saeed F, Shah YA, Hussain M, Rabail R, Socol CT, Hassoun A, Pateiro M, Lorenzo JM, Rusu AV, Aadil RM. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:999001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 83. | Aggarwal S, Sabharwal V, Kaushik P, Joshi A, Aayushi A, Suri M. Postbiotics: From emerging concept to application. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2022;6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Xie W, Zhong YS, Li XJ, Kang YK, Peng QY, Ying HZ. Postbiotics in colorectal cancer: intervention mechanisms and perspectives. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1360225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Bogdanović M, Mladenović D, Mojović L, Djuriš J, Djukić-Vuković A. Intraoral administration of probiotics and postbiotics: An overview of microorganisms and formulation strategies. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2024;60. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 86. | Franc A, Vetchý D, Fülöpová N. Commercially Available Enteric Empty Hard Capsules, Production Technology and Application. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15:1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Puccetti M, Giovagnoli S, Zelante T, Romani L, Ricci M. Development of Novel Indole-3-Aldehyde-Loaded Gastro-Resistant Spray-Dried Microparticles for Postbiotic Small Intestine Local Delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2018;107:2341-2353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Fang Y, Wang G, Zhang R, Liu Z, Liu Z, Wu X, Cao D. Eudragit L/HPMCAS blend enteric-coated lansoprazole pellets: enhanced drug stability and oral bioavailability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Gong T, Liu X, Wang X, Lu Y, Wang X. Applications of polysaccharides in enzyme-triggered oral colon-specific drug delivery systems: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;275:133623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Stefanowska K, Woźniak M, Sip A, Mrówczyńska L, Majka J, Kozak W, Dobrucka R, Ratajczak I. Characteristics of Chitosan Films with the Bioactive Substances-Caffeine and Propolis. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14:358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Yeung C, McCoubrey LE, Basit AW. Advances in colon-targeted drug technologies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2025;41:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Kedia P, Cohen RD. Once-daily MMX mesalamine for the treatment of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:919-927. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Rajput A, Pingale P, Telange D, Musale S, Chalikwar S. A current era in pulsatile drug delivery system: Drug journey based on chronobiology. Heliyon. 2024;10:e29064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | N P, Ch S, CVS S. Osmotic Controlled Release Oral Delivery System: An Overview. Int J Pharm Sci. 2024;2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 95. | Gökçe HB, Aslan İ. Novel Liposome-Gel Formulations Containing a Next Generation Postbiotic: Characterization, Rheological, Stability, Release Kinetic, and In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity Studies. Gels. 2024;10:746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Schuurman AR, Kullberg RFJ, Wiersinga WJ. Probiotics in the Intensive Care Unit. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Plaza-Diaz J, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Gil-Campos M, Gil A. Mechanisms of Action of Probiotics. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S49-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 901] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Liu M, Chen J, Dharmasiddhi IPW, Chen S, Liu Y, Liu H. Review of the Potential of Probiotics in Disease Treatment: Mechanisms, Engineering, and Applications. Processes. 2024;12:316. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 99. | Abbasi A, Hajipour N, Hasannezhad P, Baghbanzadeh A, Aghebati-Maleki L. Potential in vivo delivery routes of postbiotics. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62:3345-3369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Raina N, Pahwa R, Bhattacharya J, Paul AK, Nissapatorn V, de Lourdes Pereira M, Oliveira SMR, Dolma KG, Rahmatullah M, Wilairatana P, Gupta M. Drug Delivery Strategies and Biomedical Significance of Hydrogels: Translational Considerations. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Thorakkattu P, Khanashyam AC, Shah K, Babu KS, Mundanat AS, Deliephan A, Deokar GS, Santivarangkna C, Nirmal NP. Postbiotics: Current Trends in Food and Pharmaceutical Industry. Foods. 2022;11:3094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/