Published online Sep 5, 2024. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97261

Revised: August 9, 2024

Accepted: August 15, 2024

Published online: September 5, 2024

Processing time: 99 Days and 3.4 Hours

The gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) is a questionnaire in English language which is designed to assess the clinical symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and peptic ulcer disease. This validated scale has questions on around 15 items and has been validated in patients with dyspepsia and IBS.

To translate and validate the English version of the GSRS questionnaire to the Hindi version.

The purpose of the present work was to create a Hindi version of this question

The Hindi translation was pilot tested in 20 individuals and further validated in healthy controls (n = 30, 15 females) and diseased individuals (n = 72, 27 females). The diseased group included patients with functional dyspepsia and IBS. Cronbach's alpha for internal consistency on the final translated GSRS questionnaire was 0.715 which is considered adequate. Twelve questions significantly differentiated the diseased population from the healthy population (P value < 0.05) in the translated Hindi version of the GSRS.

The translated Hindi GSRS can be used to evaluate gastrointestinal function in clinical trials and community surveys in Hindi speaking populations.

Core Tip: The gastrointestinal symptom rating scale is a validated 15 question scale used to assess overall gastrointestinal health and has been used in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), dyspepsia and in multiple clinical trials. We translated this questionnaire into Hindi and validated it in patients with dyspepsia and IBS. The translation will allow this scale to be used in future studies in Hindi speaking populations.

- Citation: Jindal N, Jena A, Kumar K, Padhi BK, Sharma R, Jearth V, Dutta U, Sharma V. Hindi translation and validation of the English version of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale questionnaire: An observational study. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2024; 15(5): 97261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v15/i5/97261.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97261

The gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) is a questionnaire in the English language designed to assess the clinical symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and peptic ulcer disease[1]. First reported in 1988, it has since been validated for the evaluation of clinical symptoms in patients with IBS and dyspepsia[2]. This validated scale has questions on around 15 items. The instrument has also been translated to multiple other languages[3]. The scale has been used in multiple clinical and research settings apart from IBS and dyspepsia, including overall gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes, and general gastrointestinal symptoms[4]. Dyspepsia and IBS are common clinical problems that affect a large number of patients globally and have a significant mental health burden[5,6]. Therefore, the GSRS has immense value in clinical trials for these patients as it also assesses overall gastrointestinal symptoms.

The purpose of the present work was to create a Hindi version of this questionnaire for use in the Indian population. When translating a questionnaire initially established in a different nation and culture, the translation process must be able to cover all the necessary procedures to ensure that the validity and reliability of the questionnaire remain intact[7]. It is important to ensure that words in a health-related questionnaire translate accurately to the target language when translating it into a different language[8]. It is possible to decrease sample error, boost questionnaire response rates, and improve the generalizability of the results by assuring valid translation quality[9]. While the process of translating the questionnaire is included in the translation process, the process of validating the translated tool is mainly concerned with evaluating its quality[10]. The GSRS is the most relevant instrument for the evaluation of bowel function as it refers to the period in the previous week, requires a short time to complete and has easy-to-understand questions on gastrointestinal symptoms[3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has created a standardised translation methodology in response to the growing requirement to ensure high-quality translations, particularly when it comes to cross-cultural research. Therefore, we have used the WHO-suggested methodology to create a Hindi translation of the GSRS[11].

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh (PGI/IEC-INT/2023/Study-977). All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

The GSRS is a self-administered questionnaire and has 15 items that cover the gastrointestinal system: Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, bloating, constipation, bowel movements, acidity, nausea, vomiting, abdominal rumbling, and eructation. GSRS questionnaire answers have been arranged in a 4-point Likert scale in which 0 represents no or transient and 3 represents severe symptoms[1]. The GSRS questionnaire is not copyrighted.

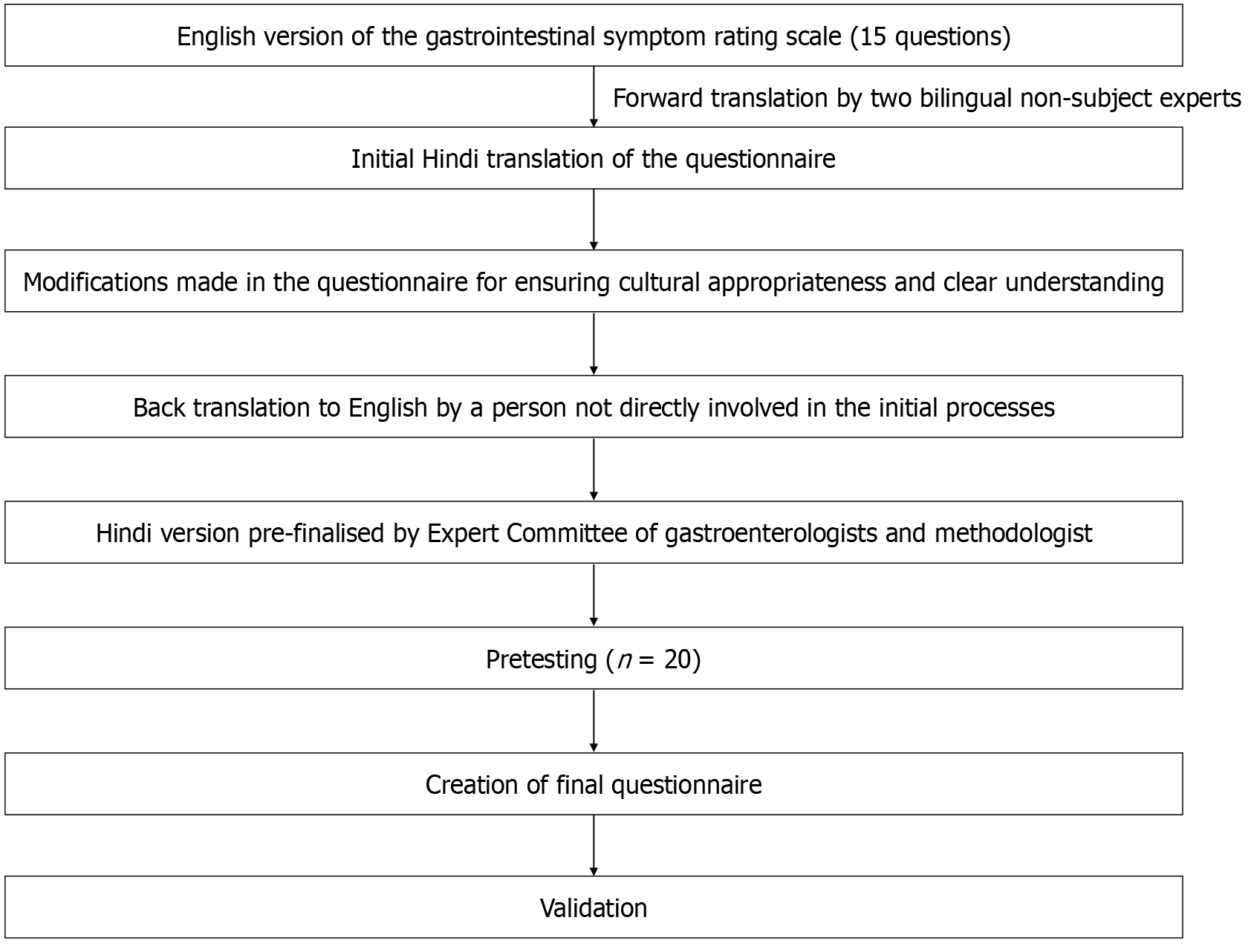

The translation methodology was followed as suggested by the WHO including forward translation, expert panel back translation, pretesting and cognitive interviewing, and the final version[11]. The committee consisted of both the forward and backward translators, a methodologist (Padhi), and specialists with knowledge of the construct of interest. Members of the expert committee reviewed all versions of the translations and a prefinal version of the questionnaire was created.

Forward translation involved two investigators who were adept at both English and Hindi (Kumar and Sharma) who translated the questionnaire into Hindi. This translation of the questionnaire was assessed by experts fluent in both English and Hindi languages (Jearth and Sharma). They evaluated the cultural acceptability of the questionnaire for our population. After modifications to ensure cultural acceptability, the Hindi version was back-translated into English by an investigator not involved in the initial process (Jena). The back translation was compared to the original translation and modifications were made to ensure that the translation was appropriate to the original work.

Pretesting and cognitive interviewing were performed in 20 disease-free individuals (Figure 1). The purpose of this was to determine whether they could understand and correctly interpret the questionnaire. As they were all bilingual, they were also provided the English version so as to comment if the Hindi version captured the essence and meaning of the questionnaire. Debriefing was conducted regarding their experience with the questionnaire and if they could repeat the questions in their own words and how they chose an answer. Following this, a final version was created.

Patients were enrolled in the outpatient department of gastroenterology. The final version was administered to dyspepsia patients and those with diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Inclusion criteria was based on ROME criteria for patients with dyspepsia and IBS. ROME IV criteria for functional dyspepsia were used which included the presence of one of the following symptoms: (1) Bothersome postprandial fullness; (2) Bothersome early satiation; (3) Bothersome epigastric pain; and (4) Bothersome epigastric burning and absence of any organic disease[12]. Similarly, the diagnosis of IBS was based on ROME IV criteria for IBS i.e. recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the following criteria: (1) Related to defecation; (2) Associated with a change in frequency of stool; and (3) Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool[13]. The symptoms should have been present for six months and the criteria fulfilled over the past 3 months. Exclusion criteria included patients who denied consent and could not understand Hindi language, were illiterate, aged < 18 years or > 65 years.

The degree of inter-correlation between the questions in the questionnaire and their consistency in measuring the same construct was indicated by internal consistency. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient, usually referred to as coefficient alpha, is frequently used to measure internal consistency[14]. Cronbach's alpha has a range of 0 to 1, with negative values occurring when there is a negative correlation between some questionnaire questions. Higher values indicate stronger interrelationships between the items, but if a negative Cronbach's alpha is still obtained after all items have been accurately scored, there are significant issues with the questionnaire's initial design. Internal consistency is absent when Cronbach's α = 0, while complete internal consistency is represented by α = 1. It has been recommended that an internal consistency of at least 0.70 on Cronbach's alpha scale be used in practice[15].

Test-retest reliability was not assessed as the scores were expected to change while on therapy which was initiated after the diagnosis.

Scores between the patients with IBS and dyspepsia were compared with controls to ascertain if the GSRS could differentiate the diseased participants from healthy participants.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, 27th version (SPSS-20, IBM) and R software version were used to analyse the data. Simple descriptive statistics involved the calculation of median and interquartile range (IQR) (or mean ± SD, depending on the normality of distribution as decided by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) for continuous variables and frequency along with percentages for the categorical variables. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the Hindi version of the scale. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the scores between the diseased participants and the controls.

A total of 117 individuals of both genders were included in the study. The group aged 16-70 years was administered the Hindi and English version of the GSRS in which 30 individuals were healthy controls (free of any known disease), 41 individuals were dyspepsia patients and 31 individuals had IBS (aged 21-66 years). Fifteen patients were excluded due to illiteracy (n = 14) and inability to understand Hindi language (n = 1). There was no disagreement or requirement for major vocabulary modifications as a result of the translation and back-translation processes (Table 1).

| Healthy controls | Diseased group | ||

| Functional dyspepsia | d-IBS | ||

| Number | 30 | 41 | 31 |

| Age (median, IQR) (years) | 19-37 (25.5, 6.75) | 16-70 (40,16.5) | 21-66 (39,12.5) |

| Male gender | 15 (50) | 28 (68) | 17 (55) |

| Duration of symptoms | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Internal consistency was estimated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha which was 0.71 and considered adequate for the final version of the questionnaire.

The score for each of the questions (median and IQR) between the patients with IBS and dyspepsia (diseased group) were compared with healthy controls as shown in Table 2. Twelve questions in the questionnaire showed significant results (P value < 0.05); however, three questions (Q5, Q10, Q13) were not significant in this study, but can be evaluated for other diseases.

| Question number | Diseased group (median, IQR) | Healthy group (median, IQR) | P value |

| Q1 | 1, 1 | 0, 1 | 0.02 |

| Q2 | 1, 2 | 0, 1 | 0.02 |

| Q3 | 1, 1 | 0, 1 | 0.04 |

| Q4 | 1, 1 | 0, 0 | 0.002 |

| Q5 | 0, 1 | 1, 1 | 0.66 |

| Q6 | 1, 1 | 0, 1 | 0.0005 |

| Q7 | 1, 2 | 0.5, 1 | 0.02 |

| Q8 | 0.5, 1 | 0, 1 | 0.04 |

| Q9 | 1, 2 | 0, 0 | < 0.001 |

| Q10 | 0, 0 | 0, 0 | 0.42 |

| Q11 | 0, 1 | 0, 0 | < 0.001 |

| Q12 | 1, 1 | 0, 0 | < 0.001 |

| Q13 | 0, 1 | 0, 1 | 0.09 |

| Q14 | 1, 1 | 0, 0 | 0.0002 |

| Q15 | 1, 2 | 0, 0 | < 0.001 |

In this work, we have translated and validated the Hindi translation of the GSRS. The GSRS is one of the most estab

In this study, we translated the English version of the GSRS into the Hindi version and validated the translated scale in dyspepsia and IBS patients. We used the standard WHO-suggested methodology to create the Hindi translation[11]. The GSRS has previously been translated and validated in the Brazilian Portuguese language for the assessment of bowel function with appropriate consistency[3]. In addition, translation into Hungarian and German languages has also been conducted[16,17]. Hindi is amongst the top five most frequently spoken languages in the world and therefore this translation of the GSRS is likely to help in research amongst a large subset of the global population.

Apart from the use of standard methodology including lingual and subject experts in the translation, the translation also demonstrates excellent internal consistency. The correlation between the questions was found to be adequate i.e. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71. There were twelve questions with significantly different responses in the diseased group (P value < 0.05). Nonetheless, three items (Q5, Q10, Q13) can be examined for different illnesses as they are not significant in this study (Table 2). Furthermore, the questions also identified the diseased population from the healthy population, suggesting the usefulness of the scale in field/community surveys. The Hindi translated version of the GSRS is therefore useful in an Indian population for the assessment of dyspepsia and IBS by clinicians. In spite of these strengths, the study has some limitations: This is a single centre study, the diseased population included only patients with dyspepsia and IBS and we could not perform test-retest reliability. Nevertheless, future studies in larger datasets would clarify the utility of this translation in various other clinical and community settings.

In conclusion, a culturally appropriate Hindi translation of the GSRS with suitable internal consistency and reliability has been created.

| 1. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1082] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Souza GS, Sardá FA, Giuntini EB, Gumbrevicius I, Morais MB, Menezes EW. Translation and Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) Questionnaire. Arq Gastroenterol. 2016;53:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kornum DS, Bertoli D, Kufaishi H, Wegeberg AM, Okdahl T, Mark EB, Høyer KL, Frøkjær JB, Brock B, Krogh K, Hansen CS, Knop FK, Brock C, Drewes AM. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation for treating gastrointestinal symptoms in individuals with diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled, multicentre trial. Diabetologia. 2024;67:1122-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ghoshal UC, Sachdeva S, Pratap N, Karyampudi A, Mustafa U, Abraham P, Bhatt CB, Chakravartty K, Chaudhuri S, Goyal O, Makharia GK, Panigrahi MK, Parida PK, Patwari S, Sainani R, Sadasivan S, Srinivas M, Upadhyay R, Venkataraman J. Indian consensus statements on irritable bowel syndrome in adults: A guideline by the Indian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association and jointly supported by the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42:249-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ghoshal U, Biswas SN, Dixit VK, Yadav JS. Anxiety and depression in Indian patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koller M, Aaronson NK, Blazeby J, Bottomley A, Dewolf L, Fayers P, Johnson C, Ramage J, Scott N, West K; EORTC Quality of Life Group. Translation procedures for standardised quality of life questionnaires: The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) approach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1810-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kalfoss M. Translation and Adaption of Questionnaires: A Nursing Challenge. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019;5:2377960818816810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Danielsen AK, Pommergaard HC, Burcharth J, Angenete E, Rosenberg J. Translation of questionnaires measuring health related quality of life is not standardized: a literature based research study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Leplege A, Verdier A. The adaptation of health status measures: methodological aspects of the translation procedure. In: Shumaker SA, Berzon RA, editors. The international assessment of health-related quality of life: theory, translation, measurement and analysis. Oxford: Rapid Communications, 1995: 93–101. |

| 12. | Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 1033] [Article Influence: 103.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 2029] [Article Influence: 202.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 14. | Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:S80-S89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 96.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297-334. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Kulich RK, Ujszászy L, Tóth GT, Bárány L, Carlsson J, Wiklund I. Psychometric validation of the Hungarian translation of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) and quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in patients with reflux disease. Orv Hetil. 2004;145:723-729, 739. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kulich KR, Malfertheiner P, Madisch A, Labenz J, Bayerdörffer E, Miehlke S, Carlsson J, Wiklund IK. Psychometric validation of the German translation of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in patients with reflux disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/