Published online Dec 12, 2023. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v14.i5.39

Peer-review started: September 29, 2023

First decision: October 8, 2023

Revised: October 16, 2023

Accepted: November 15, 2023

Article in press: November 15, 2023

Published online: December 12, 2023

Processing time: 73 Days and 12 Hours

Amino-acid based medical foods have shown promise in alleviating symptoms of drug induced gastrointestinal side effects; particularly, diarrhea-predominant symptoms. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a gastrointestinal disorder that affects up to 9% of people globally, with diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) being the most prevalent subtype. Further trials are needed to explore potential added benefits when integrated into standard care for IBS-D.

To assess the effectiveness of an amino acid-based medical food as an adjunct to standard of care for adults with IBS-D.

This is a pragmatic, real world, open label, single arm study comparing a 2-week baseline assessment to a 2-week intervention period. One hundred adults, aged 18 to 65 years, with IBS-D, according to Rome IV criteria, were enrolled after com

The test product was well-tolerated as each participant successfully completed the full 14-day trial, and there were no instances of dropouts or discontinuation of the study product reported. Forty percent of participants achieved a 50% or more reduction in the number of days with type 6-7 bowel movements (IBS-D stool consistency res

The amino acid-based medical food was well-tolerated, when added to the standard of care, and demonstrated improvements in both overall IBS symptom severity and IBS-D symptoms within just 2 wk.

Core Tip: Amino-acid based medical foods have been shown to alleviate symptoms of drug induced gastrointestinal side effects, especially diarrhea severity. Diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder that affects up to 9% of people worldwide. In this pragmatic, real-world study, an amino acid beverage was demonstrated to be tolerable and efficacious when used as an adjunct to standard of care for adults with IBS-D. Participants demonstrated improvements in both overall irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity and IBS-D symptoms within just two weeks. These results suggest that this amino acid-based beverage can be safely integrated into IBS-D standard of care for symptom improvement.

- Citation: Niles SE, Blazy P, Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW, Vidyasagar S, Smith AB, Fawkes N, Denman W. Effectiveness of an amino acid beverage formulation in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A pragmatic real-world study. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2023; 14(5): 39-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v14/i5/39.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v14.i5.39

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and debilitating gastrointestinal disorder with a population prevalence of 4%-5% in North America and 4%-9% globally[1,2]. Healthcare professionals employ the Rome IV criteria for diagnosis and treatment decisions. As defined by Rome IV criteria, the predominant diagnosis for IBS is the presence of recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort in conjunction with changes in bowel habits[3]. IBS is further categorized based on the primary stool pattern, with 40% of IBS patients experiencing changes in stool frequency and consistency equating to diarrhea, thus making diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) the most prevalent subtype of the syndrome[4] and one of the most common causes of chronic diarrhea within the United States (est. 5% general population)[5]. International gastro

The management of patients with IBS is tailored to the individual and a holistic approach is recommended that can include dietary, lifestyle, medical and behavioral interventions[9]. While diet modifications such as low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diets are recommended to help alleviate global symptoms[10], strict food avoidance can become unsustainable for some patients and can also compound malabsorption nutrient deficits[11,12]. More specifically, these dietary recommendations do not address water and electrolyte losses that result from diarrhea suffered by IBS-D patients[13,14]. The correction and replacement of these nutrients often go overlooked, with the mainstay of treatment strategy focusing instead on treatments to reduce diarrhea[15].

Providing nutritional support for other conditions where patients suffer from recurrent watery diarrhea has been demonstrated to be a successful approach. For example, an amino acid based medical food is being used by patients undergoing cancer treatments who suffer from prolonged watery diarrhea associated with radiation and chemotherapy. The effects of chemotherapy on the small intestine include nutrient malabsorption, hypersecretion (diarrhea), and increased intestinal permeability[16,17]. Select amino acid formulations have been shown to reduce secretions and improve nutrient absorption in animals[18].

The present study investigated a medical food which contains a select amino acid blend, in combination with ingredients designed specifically to support IBS-D nutritional deficits occurring with diarrhea[11,12]. The objective was to assess the tolerability of the product when added to the standard of care in adults with IBS-D, whilst also measuring any additional benefits conferred to functional gastrointestinal symptoms in a pragmatic real-world setting.

The study population consisted of adults between the ages of 18 and 65 years, residing across the United States, who had received a confirmed diagnosis of IBS-D from a qualified physician. Recruitment for this study was conducted through a decentralized approach, leveraging virtual platforms and online resources to reach and engage eligible participants nationwide. To confirm adherence to the Rome IV criteria, participants underwent a 2-week run-in period during which they utilized an electronic diary each day to record their predominant stool type on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS)[6] and the severity of abdominal pain/discomfort using numeric rating scales graded on an 11-point scale. Eligibility for the study was determined by specific criteria: participants had to experience diarrhea, defined as stool types 6 and 7 on the BSFS, occurring at least four times weekly and constituting the predominant (> 25%) stool pattern. Additionally, they were required to report abdominal pain and/or discomfort occurring at least once a week and possess a Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index (FBDSI) score exceeding 60[19]. Throughout their participation in the trial, eligible participants were allowed to maintain their current therapeutic regimens, supplements, and dietary practices.

Exclusion criteria encompassed a diagnosis of IBS-C or unclassified IBS according to the Rome IV criteria, as well as diagnoses of other gastrointestinal disorders such as Crohn's disease, colitis, and celiac disease. Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding were ineligible for participation. Additionally, patients with known allergies to the com

The clinical study was conducted in a fully decentralized manner within the United States, adhering to the principles outlined in the International Council on Harmonization E6 Good Clinical Practice, and in compliance with local re

This is a pragmatic real-world study, conducted in an open-label, single-arm design, comparing a 2-week baseline assessment to a subsequent 2-week intervention period. The study was administered through the Laina Clinical Research Platform. The study population was recruited via virtual channels, including online advertisements, and in partnership with the Walmart Health Research Institute, which facilitated the validation of participants' health records and physician diagnoses after obtaining informed consent. Eligible participants underwent a 2-week run-in period to assess baseline parameters, thereby informing their inclusion in the study. Data were collected electronically through a mobile phone application with participants engaged in completing daily electronic diaries.

Participants enrolled into the intervention trial period received sixteen 16-ounce bottles of enterade® IBS-D and were instructed to drink 8-ounces once in the morning (30 min prior to eating) and 8-ounces once in the evening (30 min prior to eating) for 14 d. Each day during the intervention period, participants filled out daily symptom diaries with outcome measures described below. Additionally, validated surveys from the Rome Foundation were used to monitor patient reported IBS-D associated symptoms, including the IBS-Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS)[20] and the Global Improvement Survey (GIS)[21]. Participants filled out the IBS-SSS on days 0 and 14, and the GIS on day 14 as a final questionnaire about the overall study experience. Day 0 was the last day (day 14) of the run-in period, whereas day 14 was the last day of the intervention period.

The amino acid based medical food beverage used in this study was enterade® IBS-D, which contains a patented blend of plant-based amino acids (valine, aspartic acid, serine, threonine, tyrosine), electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride), vitamins (ascorbic acid), and minerals (zinc, copper, calcium) carefully selected to help replenish the loss of water, electrolytes and other nutrients that occur secondary to frequent diarrhea and help to support and maintain normal digestive function in IBS-D. The liquid product (mixed berry lot IBSD-0001; orange lot IBSD-0002) is specially ma

The primary outcome, measure of tolerability, was assessed by the number of Adverse Events (AEs) spontaneously reported by participants for the duration of the study. Any event occurring after obtaining participant consent was recorded as an AE, which was defined as any unfavorable and unintended diagnosis, symptom, sign, syndrome, or disease which either occurred during the study, having been absent at baseline, or if present at baseline, appeared to worsen. All AEs were recorded according to the common terminology criteria for AEs (CTCAE Version 6.0), regardless of their relationship to the study intervention.

The Food and Drug Administration emphasizes the difference between statistical significance and clinical relevance in their IBS guidance for industry[22]. While our product is a medical food, where relevant we examined potential product benefits for secondary outcomes considering clinically based rules, including ‘responder’ analyses[22] and minimally clinically important differences (MCID)[23]. Stool consistency was assessed via the BSFS, a validated ordinal scale of stool types ranging from 1 through 7, with types 6-7 being indicative of diarrhea. BSFS responders were defined as those with a 50% decrease in the number of days per week with at least one type 6-7 bowel movement relative to baseline which meets the level of a “responder”. Baseline is defined here as the 2-week run-in period. The number of days were included for the baseline across both weeks of the run-in, and a similar approach was taken for week 2 of the trial period.

Abdominal pain and discomfort severity was assessed via an 11-point numeric rating scale (APS-NRS)[23], with 10 representing most severe pain and 0 representing no pain. Pain responders and discomfort responders were defined as those participants recording a 30% decrease in, respectively, the mean weekly pain and discomfort score on the NRS. The average pain/discomfort was calculated across the 2-week run-in period and compared to the average pain/discomfort scores in week 2 of the trial period.

Urgency or severity of urgency was recorded on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (None) to 4 (Severe urgency). Improvement and/or worsening on the urgency scale was defined as the difference between the maximum urgency score at baseline (2-week run-up) and during the trial period. Category changes were derived (maximum urgency trial period minus maximum urgency at baseline) and designated as follows: “Significant improvement/worsening”, a 3-category change; “moderate improvement/worsening”, 2-category change; “improvement /worsening”, and 0, "No change”.

The change in IBS symptom severity, assessed via the IBS-SSS total score[20] was assessed from baseline to day 14. Scores on the IBS-SSS range from 0 to 500, with five domains related to abdominal pain severity and frequency, abdominal distention, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference with quality of life. A decrease of 95 points has been associated with a clinically meaningful improvement[23] and was used for classification of IBS-SSS responders.

Study data are summarized using means (SD). The denominator to determine the percentage of participants in each category is based on the number of participants with complete paired data unless otherwise noted. A descriptive analysis was used for the primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes. The IBS-SSS efficacy analysis evaluated the changes (day 0 vs day 14) using a paired t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using R package 1.3-0 or GraphPad Prism v 9.4.0.

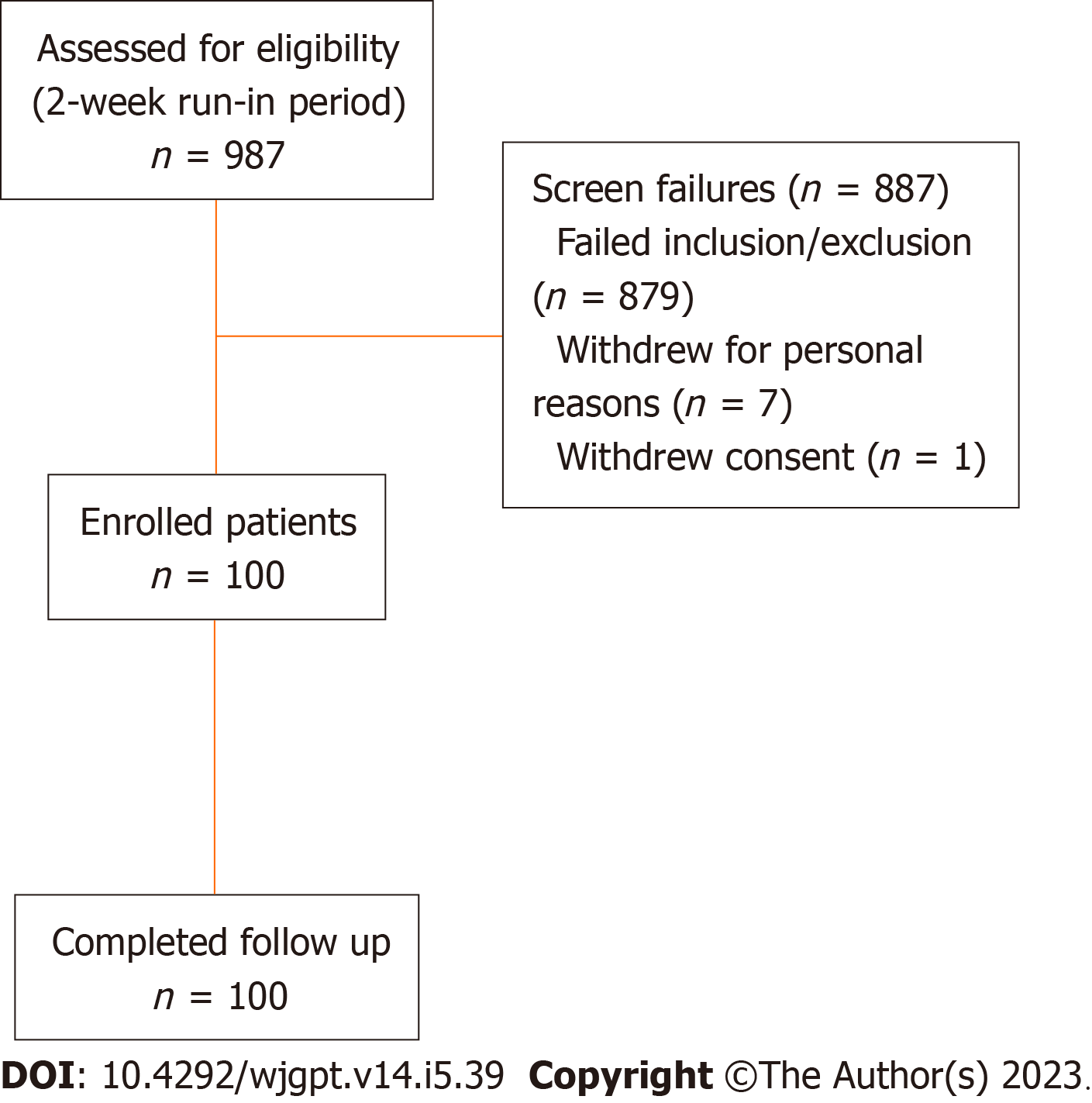

A total of 987 screened patients who participated in the 2-week run were assessed for eligibility and 100 participants were enrolled into the study intervention period (Figure 1). Enrollment and intervention occurred continuously from October 2022 through May 2023. All 100 participants who participated in the 2-week intervention period completed the study.

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age of participants were 39.7 (SD 10.6), with 67% being female. All patients met the ROME IV criteria for IBS-D and had baseline mean IBS-SSS and FBDSI scores of 314 (77) and 195 (52.6) respectively. The average BSFS and APS-NRS scores were 6 (0.1) and 6 (0.2) respectively. The average IBS-SSS, BSFS and APS-NRS scores indicate moderate to severe IBS-D symptomology at study outset. A summary of the standard of care therapies is provided in Table 2.

| Characteristic | n = 1001 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 67 (67%) |

| Male | 33 (33%) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 39.7 (10.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 8 (8%) |

| Asian | 2 (2%) |

| Black | 9 (9%) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander | 1 (1%) |

| White | 80 (80%) |

| Hispanic | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (10%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 90 (90%) |

| IBS-D features | |

| Met Rome IV Criteria | 100 (100%) |

| Number of patients with > 4 d experiencing type 4/5 stools | 100 (100%) |

| Average BSFS | 6 (0.1) |

| Average pain-NRS | 6 (0.2) |

| IBS-SSS2 | 314 (77) |

| FBDSI | 195 (52.6) |

| Dietary modifications | n = 1001 | Concomitant supplements | n = 1001 | Concomitant medication | n = 1001 |

| FODMAP | 50 (50%) | Prebiotics | 60 (60%) | Rifaximin | 35 (35%) |

| Gluten-free | 51 (51%) | Probiotics | 76 (76%) | Eluxadoline | 22 (22%) |

| Keto | 36 (36%) | Peppermint oil | 45 (45%) | Antispasmodics | 12 (12%) |

| Elimination | 50 (50%) | Fiber | 86 (86%) | SSRIs | 8 (8%) |

| High fiber | 53 (53%) | Ginger | 52 (52%) | Tricyclic antidepressant | 8 (8%) |

| Low fiber | 43 (43%) | Magnesium | 55 (55%) | Anticholinergic medication | 14 (14%) |

| - | - | Vitamin D | 57 (57%) | Antidiarrheal medications | 32 (32%) |

| - | - | - | - | Bile acid sequestrants | 9 (9%) |

| - | - | - | - | Ondansetron | 8 (8%) |

Tolerance to the amino acid-based medical food, taken twice daily for a period of 14 d, was excellent. Every participant successfully completed the full 14-day trial, and there were no instances of dropouts or discontinuation of the study product reported. Only two Treatment Emergent AEs were spontaneously reported over the course of the study. Both events were reported by the same participant, who experienced a bout of abdominal bloating followed by a temporary increase in abdominal discomfort. The AEs were characterized as mild, and they were self-limiting, with no need for discontinuation of the test product. Importantly, neither of these events was deemed to be a serious adverse event.

Table 3 shows the responder analysis for the secondary outcomes of the study. The number of IBS-D stool consistency responders, based on a decrease of 50% or more in the number of days per week with at least on type 6-7 bowel movement, as compared to baseline was 40 (40%). The number of IBS-D pain and discomfort responders who exceeded a clinically meaningful threshold with a reduction of 30% mean weekly pain and discomfort were 51 (53%) and 53 (55%) respectively. The number of participants who achieved both clinically meaningful responses in pain/stool consistency or discomfort/stool consistency were 24 (25%) for both composite endpoints. Table 4 presents the overall improvement in the amount of urgency experienced by participants, with 58% of participants achieving some level of improvement.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| BSFS responder (n = 100) | 40 (40%) |

| Pain responder (n = 96) | 51 (53%) |

| Discomfort responder (n = 96) | 53 (55%) |

| Composite responder (pain) (n = 96) | 24 (25%) |

| Composite responder (discomfort) (n = 96) | 24 (25%) |

| IBS-SSS (n = 71) | 36 (51%) |

| Urgency | n = 981 |

| Category change | |

| Significant improvement | 8 (8%) |

| Moderate improvement | 9 (9%) |

| Mild improvement | 40 (41%) |

| No change | 40 (41%) |

| Mild worsening | 1 (1%) |

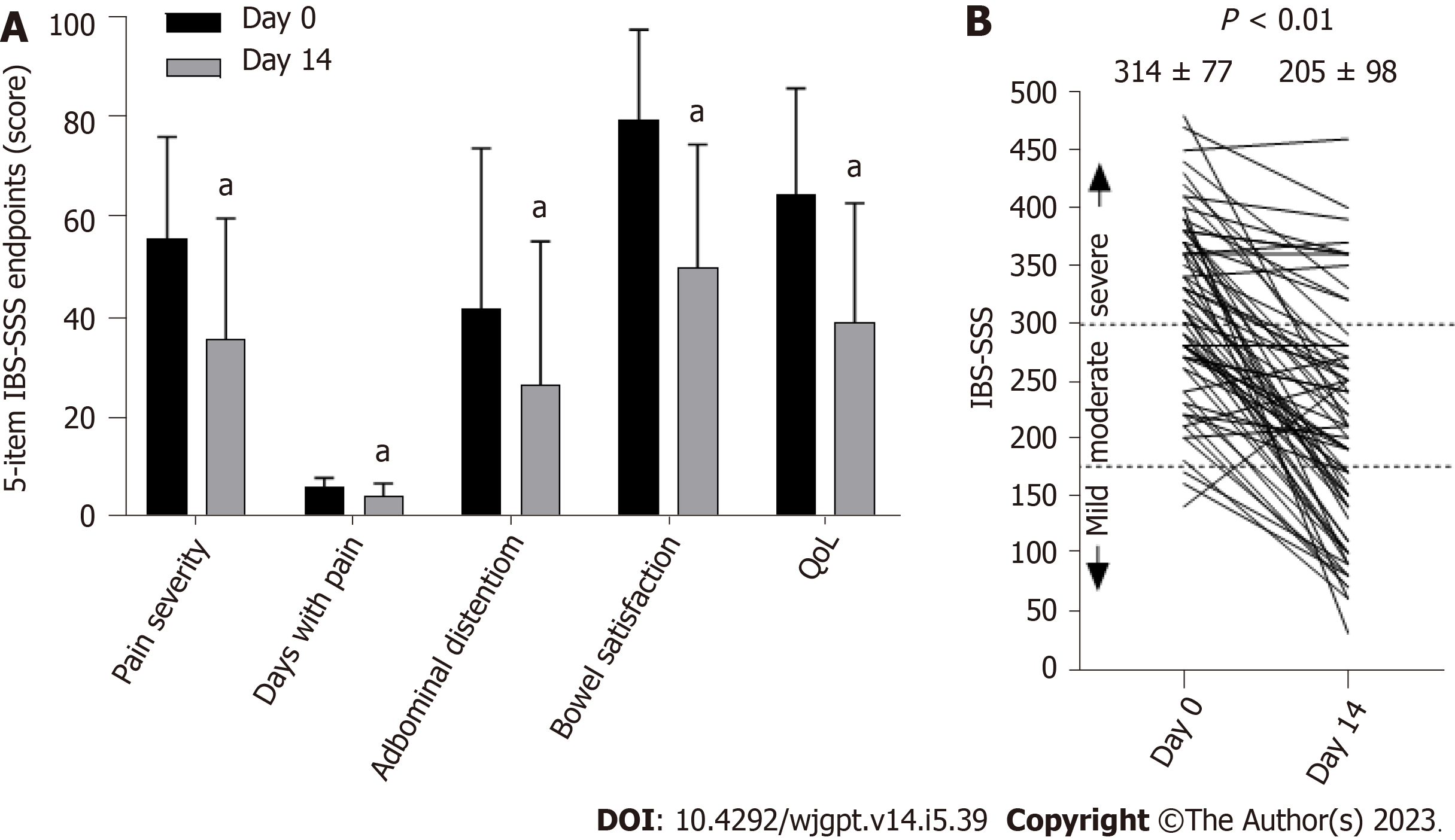

Seventy-one participants provided complete IBS-SSS data on days 0 and 14 for pairwise comparison. Figure 2 illustrates the differences in each of the 5-item IBS-SSS endpoints and their significant improvement over 14 d. Individual and significant average changes in the aggregate IBS-SSS experienced by participants are shown in Figure 2. Three participants began the study with mild scores (75 to 175; 4%), n = 29 began with moderate scores (176 to 300; 41%), and n = 39 began with severe scores (301 to 500; 55%). Overall, 75% (53/71) of participants experienced a reliable clinical score improvement (Figure 2). In addition, 51% of participants experienced ≥ 95-point score improvement, often considered the MCID[23]. The mean score reduction (-109.4, 95% confidence interval: -130.1, -88.8) exceeded both thresholds[20,23]. A category shift from severe to moderate or mild occurred in 69% of participants (27/39) and a shift from moderate to mild categories occurred in 52% of participants (15/29), such that 62% (42/68) of the total moderate to severe IBS-SSS sufferers experienced a full IBS-SSS category improvement. Seventy-six percent of participants (54/71) reported relief on the GIS after 14 d of amino acid beverage consumption.

The purpose of this open-labeled, home-use study was to evaluate the tolerability and functional impact of a select amino acid blended medical food in 100 confirmed IBS-D participants using validated survey instruments from the Rome Foundation. The study design was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of an amino acid-based medical food in a pragmatic setting. This approach employed a decentralized methodology to enroll a diverse range of participants while minimizing disruptions to routine care, thereby ensuring that the study findings are relevant to real-world clinical practice. Strict enrollment criteria ensured that participants had recurring watery diarrhea. Further, the 2-weeks of daily consumption of an amino acid-based medical food demonstrated that the product was safe and tolerable in 100% of the population tested and had a significant positive impact on the exploratory variables assessed.

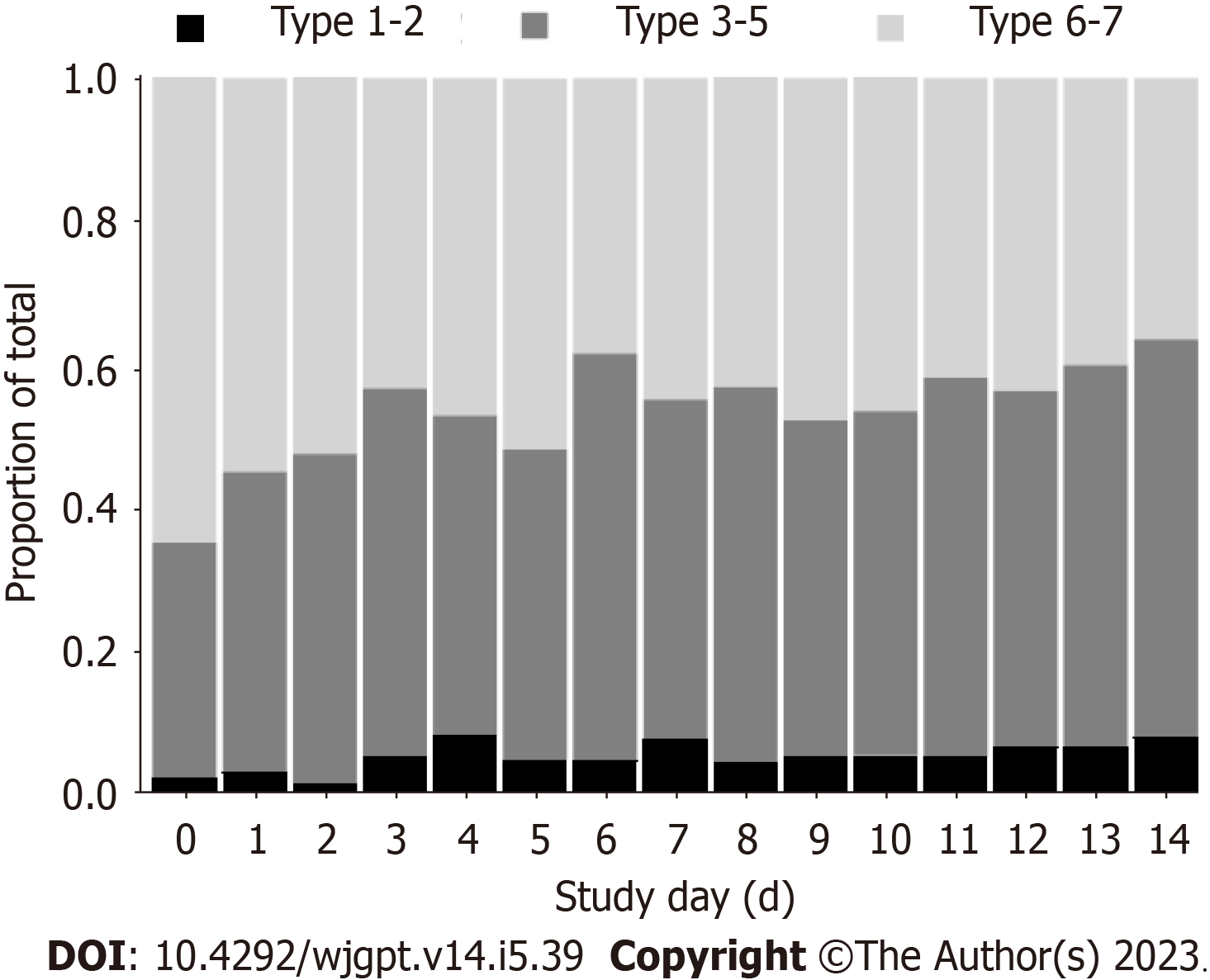

The daily consumption of approximately 474 mL (16 fl. oz.) of an amino acid-based medical food beverage for 2-weeks drastically reduced the group percentage of BSFS 6-7 from 65% to 36% (Figure 2). Chronic diarrhea in IBS-D may double or triple ordinary stool frequency[3]. In conjunction with stool quality of BSFS 6-7[7], IBS-D may increase daily bowel water losses to 500 mL[6,24] along with accompanying salt losses[8,25]. Although no measures of hydration status were made in this study, the complement of approximately 474 mL of fluid with approximately 30 mmol/L of key electrolytes consumed daily, alongside a significant reduction in BSFS from liquid to solid, makes plausible an improvement in whole body hydration status over the 2-weeks. The improvements in BSFS over the 14-day product intervention period are entirely consistent with the reduced stool frequency benefits reported in previous studies consuming amino acid-based beverages with ancillary compositional differences to the product tested herein[26-29]. Hypotonic oral rehydration therapy is widely recognized as the preferred intervention for diarrhea and dehydration independent of etiology[13,30,31]. However, a dual action product that rehydrates while reducing gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. diarrhea), as reported in this study, has not been previously demonstrated[32].

The IBS-SSS is a widely used consensus-based measurement of IBS-D severity[20]. Consumption of an amino acid beverage for 2-weeks resulted in improvements on all 5-IBS-SSS survey items (Figure 3A). The mean overall impro

While an open label study improves ecological validity, there are some inherent limitations to this study design. First, evaluations were based exclusively on patient reported outcomes and the possible involvement of the placebo effect in the results cannot be excluded. Since pooled estimates of placebo response are estimated[35-37] to range from 22% for composite pain and stool assessments, 39.6% for pain and discomfort, 33% stool consistency, and 43% for IBS-SSS it is acknowledged that placebo response rate is quite high and inconsistent across studies. Even when taking this into consideration, the present study verified that an amino acid based medical food can confer additional health benefits when used as an adjunct to the standard of care (Table 3) in line with clinically meaningful improvements beyond common placebo effects recorded in the above cited literature.

Second, the short duration of this pilot trial can be viewed as both a limitation and a benefit. The limitation resides in the fact that IBS-D is a lifelong, chronic condition so the durability of benefit observed after 2 weeks remains unknown. The benefit is the observed significance and magnitude of effects on par with other dietary interventions used for much longer time periods. Of note, low FODMAP diets are recommended by consensus for IBS[10] and often produce excellent outcomes (e.g., Russo et al[38]). But unlike a daily amino acid beverage, low FODMAP diets can become impractical, tiresome, and even unhealthy as a long-term solution for IBS-D.

Finally, the study was structured intentionally to provide real-world patient experiences (open-label, standard of care) within a controlled clinical trial framework. This approach yields valuable insights into the practical use, benefits, and risks of using a medical food as an adjunct (rather than a replacement) to existing care, demonstrating its effectiveness in broader healthcare settings. However, while the use of patient reported outcomes in IBS research is essential[39], future studies that include direct blood and fecal markers will complement and add strength to the conclusions drawn from pragmatic studies like this one.

Importantly, this study addresses the replenishment of water and nutrients lost due to diarrhea in IBS-D patients, which is a nutritional complement to the gut benefits afforded by the amino acids. Until now, there has not been a specifically formulated medical food available to address the nutritional deficits experienced by IBS-D patients[11,12,24]. As previously mentioned, the most recent guidelines for managing patients with IBS emphasize the importance of tailoring treatments to individual needs and adopting a holistic approach that encompasses dietary, lifestyle, medication, and behavioral interventions[10]. The open label study design in the present study exemplifies this approach, as participants were employing all the previously mentioned modalities and practices. It is also important to note that despite the use of these modalities and practices (Table 2), participants in the study did exhibit recurring watery diarrhea to the degree that met inclusion criteria for participation in the study. However, the positive improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms reported in the present study demonstrate that this specifically formulated medical food can be used in conjunction with other approaches.

Patient reported outcomes collected in this pragmatic study provide evidence that the integration of an amino acid-based medical food as an adjunct to the standard care for patients with IBS-D is both feasible and well-tolerated. Furthermore, the improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms demonstrated statistically significant benefits with an order of mag

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits. Diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) is the most prevalent subtype, causing chronic and debilitating diarrhea. This study explores the potential benefits of an amino acid based medical food, enterade® IBS-D, to address nutritional deficits in IBS-D patients and improve their gastrointestinal symptoms, aiming to provide an additional means to management.

The motivation to perform this research was to discover additional therapies to aid in the management of chronic diarrhea and associated symptomology resulting from IBS-D.

The study primarily focused on the tolerability of the amino acid based medical food by monitoring adverse events (AEs) reported by participants. Secondary outcomes were assessed using a number of clinical criteria, including changes in stool consistency [Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS)], reduction in abdominal pain and discomfort, improvement in bowel urgency, and changes in the overall IBS-Severity Scoring System. The study considered both statistical significance and clinical relevance as recommended by the Food and Drug Administration for IBS-related assessments.

The study used a decentralized, open-label, single-arm design, with data collected electronically through the Laina Clinical Research Platform during a 2-week baseline assessment and a subsequent 2-week intervention period, where participants consumed enterade® IBS-D. The study included adults aged 18-65, diagnosed with IBS-D in the United States. Participants were evaluated during a 2-week run-in period to confirm their diagnosis using Rome IV criteria. Eligible participants needed to experience diarrhea at least four times weekly (BSFS types 6 and 7), along with abdominal pain/discomfort and a Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index score above 60. Exclusion criteria included other IBS subtypes, gastrointestinal disorders, pregnancy/breastfeeding, allergies to the test product components, and anticipated medication changes that could affect bowel habits. Outcome measures included daily symptom diaries, the IBS-Severity Scoring System, and the Global Improvement Survey (GIS) from the Rome Foundation.

The study involved 100 participants with IBS-D who completed a 2-week intervention period. All participants met ROME IV criteria for IBS-D, and their baseline IBS severity scoring system (IBS-SSS) score and FBDSI scores indicated moderate to severe symptomology. Tolerance to the amino acid-based medical food was exceptional, with no dropouts or discontinuations, and only two mild AEs reported. Responder analysis for secondary outcomes revealed that 40% of participants achieved a 50% or more decrease in days with type 6-7 bowel movements. Additionally, 53% and 55% experienced clinically meaningful reductions in pain and discomfort, respectively. About 25% of participants achieved meaningful responses in both pain/stool consistency or discomfort/stool consistency. Fifty-eight percent of participants showed improvements in urgency. IBS-SSS data demonstrated significant improvement, with 75% experiencing a reliable clinical score improvement, 51% achieving a ≥ 95-point score improvement, and a category shift from severe to moderate or mild in 69% of participants. Furthermore, 76% reported relief on the GIS after 14 d of amino acid beverage consumption.

The study suggests that adding an amino acid-based medical food to the standard care for IBS-D patients is practical and well-tolerated. The improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms were statistically significant and comparable to longer nutrition intervention trials, making this amino acid beverage a promising adjunct for relieving IBS-D symptoms.

While patient reported outcomes in IBS research are crucial endpoints, future studies that include collection of biological samples, such as direct blood and fecal markers, will supplement and strengthen the conclusions that have been drawn from this pragmatic study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Christodoulidis G, Greece; He L, China; Tu J, China; Ulasoglu C, Turkey S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Lin C

| 1. | Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, Sperber AD, Simren M. Prevalence of Rome IV Functional Bowel Disorders Among Adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1262-1273.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:908-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1781] [Cited by in RCA: 2008] [Article Influence: 200.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Lembo A, Sultan S, Chang L, Heidelbaugh JJ, Smalley W, Verne GN. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:137-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gorospe EC, Oxentenko AS. Nutritional consequences of chronic diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:663-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1858] [Cited by in RCA: 2200] [Article Influence: 75.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Rome Foundation. ROME IV Diagnostic Criteria. 2016. [cited 20 September 2023]. Available from: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/. |

| 8. | Gennari FJ, Weise WJ. Acid-base disturbances in gastrointestinal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1861-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 629] [Cited by in RCA: 773] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, Chey WD, Keefer LA, Long MD, Moshiree B. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:17-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 105.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bek S, Teo YN, Tan XH, Fan KHR, Siah KTH. Association between irritable bowel syndrome and micronutrients: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1485-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hujoel IA. Nutritional status in irritable bowel syndrome: A North American population-based study. JGH Open. 2020;4:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barr W, Smith A. Acute diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:180-189. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ford CK. Nutrition Considerations in Patients with Functional Diarrhea. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2023;25:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Savarino E, Zingone F, Barberio B, Marasco G, Akyuz F, Akpinar H, Barboi O, Bodini G, Bor S, Chiarioni G, Cristian G, Corsetti M, Di Sabatino A, Dimitriu AM, Drug V, Dumitrascu DL, Ford AC, Hauser G, Nakov R, Patel N, Pohl D, Sfarti C, Serra J, Simrén M, Suciu A, Tack J, Toruner M, Walters J, Cremon C, Barbara G. Functional bowel disorders with diarrhoea: Clinical guidelines of the United European Gastroenterology and European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:556-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wardill HR, Bowen JM, Gibson RJ. Chemotherapy-induced gut toxicity: are alterations to intestinal tight junctions pivotal? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70:627-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wardill HR, Bowen JM, Al-Dasooqi N, Sultani M, Bateman E, Stansborough R, Shirren J, Gibson RJ. Irinotecan disrupts tight junction proteins within the gut : implications for chemotherapy-induced gut toxicity. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:236-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yin L, Gupta R, Vaught L, Grosche A, Okunieff P, Vidyasagar S. An amino acid-based oral rehydration solution (AA-ORS) enhanced intestinal epithelial proliferation in mice exposed to radiation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Drossman DA, Li Z, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Creed FH, Thompson D, Read NW, Babbs C, Barreiro M, Bank L. Functional bowel disorders. A multicenter comparison of health status and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 973] [Cited by in RCA: 1284] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Gordon S, Ameen V, Bagby B, Shahan B, Jhingran P, Carter E. Validation of irritable bowel syndrome Global Improvement Scale: an integrated symptom end point for assessing treatment efficacy. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1317-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry on Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Clinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment. Apr 31, 2012 [cited 20 September 2023]. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/05/31/2012-13143/guidance-for-industry-on-irritable-bowel-syndrome-clinical-evaluation-of-drugs-for-treatment. |

| 23. | Spiegel B, Bolus R, Harris LA, Lucak S, Naliboff B, Esrailian E, Chey WD, Lembo A, Karsan H, Tillisch K, Talley J, Mayer E, Chang L. Measuring irritable bowel syndrome patient-reported outcomes with an abdominal pain numeric rating scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1159-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:693-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Do C, Evans GJ, DeAguero J, Escobar GP, Lin HC, Wagner B. Dysnatremia in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:892265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hendrie JD, Chauhan A, Nelson NR, Anthony LB. Can an amino acid-based oral rehydration solution be effective in managing immune therapy-induced diarrhea? Med Hypotheses. 2019;127:66-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Luque L, Cheuvront SN, Mantz C, Finkelstein SE. Alleviation of Cancer Therapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicity using an Amino Acid Medical Food. Food Nutr J. 2020;5:216. |

| 28. | Chauhan A, Das S, Miller R, Luque L, Cheuvront SN, Cloud J, Tarter Z, Siddiqui F, Ramirez RA, Anthony L. Can an amino acid mixture alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms in neuroendocrine tumor patients? BMC Cancer. 2021;21:580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | De Filipp Z, Glotzbecker B, Luque L, Kim HT, Mitchell KM, Cheuvront SN, Soiffer RJ. Randomized Study of enterade® to Reduce Diarrhea in Patients Receiving High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Duggan C, Fontaine O, Pierce NF, Glass RI, Mahalanabis D, Alam NH, Bhan MK, Santosham M. Scientific rationale for a change in the composition of oral rehydration solution. JAMA. 2004;291:2628-2631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ofei SY, Fuchs GJ 3rd. Principles and Practice of Oral Rehydration. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Thiagarajah JR, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Secretory diarrhoea: mechanisms and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:446-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gayoso L, Garcia-Etxebarria K, Arzallus T, Montalvo I, Lizasoain J, D'Amato M, Etxeberria U, Bujanda L. The effect of starch- and sucrose-reduced diet accompanied by nutritional and culinary recommendations on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome patients with diarrhoea. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231156682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fukushima Y, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Kiyosue A, Hibi T. Efficacy of Solifenacin on Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea: Open-label Prospective Pilot Trial. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:317-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, Schey R, Dove LS, Andrae DA, Davenport JM, McIntyre G, Lopez R, Turner L, Covington PS. Eluxadoline for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:242-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gunn D, Topan R, Barnard L, Fried R, Holloway I, Brindle R, Corsetti M, Scott M, Farmer A, Kapur K, Sanders D, Eugenicos M, Trudgill N, Whorwell P, Mclaughlin J, Akbar A, Houghton L, Dinning PG, Aziz Q, Ford AC, Farrin AJ, Spiller R. Randomised, placebo-controlled trial and meta-analysis show benefit of ondansetron for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea: The TRITON trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57:1258-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Weinstock LB, Paterson C, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Repeat Treatment With Rifaximin Is Safe and Effective in Patients With Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:1113-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Russo F, Riezzo G, Orlando A, Linsalata M, D'Attoma B, Prospero L, Ignazzi A, Giannelli G. A Comparison of the Low-FODMAPs Diet and a Tritordeum-Based Diet on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Profile of Patients Suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Diarrhea Variant (IBS-D): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Spiegel B. Polarizing or paralyzing? Moving forward with patient reported outcome measurement in irritable bowel syndrome. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2013;78:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |