Published online Aug 15, 2016. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v7.i3.288

Peer-review started: December 28, 2015

First decision: January 30, 2016

Revised: June 5, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

Published online: August 15, 2016

Processing time: 226 Days and 20.9 Hours

AIM: To investigate the relationship between serum titers of anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) immunoglobulin G (IgG) and hepatitis B virus surface antibody (HBsAb).

METHODS: Korean adults were included whose samples had positive Giemsa staining on endoscopic biopsy and were studied in the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg)/HBsAb serologic assay, pepsinogen (PG) assay, and H. pylori serologic test on the same day. Subjects were excluded if they were positive for HBsAg, had a recent history of medication, or had other medical condition(s). We analyzed the effects of the following factors on serum titers of HBsAb and the anti-H. pylori IgG: Age, density of H. pylori infiltration in biopsy samples, serum concentrations of PG I and PG II, PG I/II ratio, and white blood cell count.

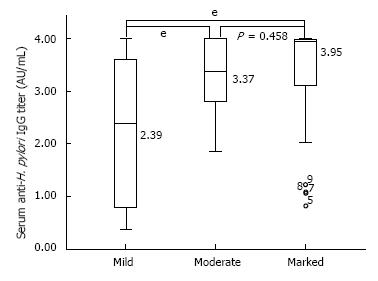

RESULTS: Of 111 included subjects, 74 (66.7%) exhibited a positive HBsAb finding. The serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer did not correlate with the serum HBsAb titer (P = 0.185); however, it correlated with the degree of H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy (P < 0.001) and serum PG II concentration (P = 0.042). According to the density of H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy, subjects could be subdivided into those with a marked (median: 3.95, range 0.82-4.00) (P = 0.458), moderate (median: 3.37, range 1.86-4.00), and mild H. pylori infiltrations (median: 2.39, range 0.36-4.00) (P < 0.001). Subjects with a marked H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy had the highest serological titer, whereas in subjects with moderate and mild H. pylori infiltrations titers were correspondingly lower (P < 0.001). After the successful eradication, significant decreases of the degree of H. pylori infiltration (P < 0.001), serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer (P < 0.001), and serum concentrations of PG I (P = 0.028) and PG II (P = 0.028) were observed.

CONCLUSION: The anti-H. pylori IgG assay can be used to estimate the burden of bacteria in immunocompetent hosts with H. pylori infection, regardless of the HBsAb titer after HBV vaccination.

Core tip: Koreans receive a routine childhood immunization program, including hepatitis B vaccinations, but serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antibody responses are variable. It is unclear whether the beneficial functional immune aspects inherent in vaccine responders can be translated into a robust immune response after Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. In this study, the serum anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer appears to be significantly linked to the bacterial load of the stomach, regardless of the ability of antibody production after HBV vaccination. The serum anti-H. pylori IgG assay can be used to estimate the burden of bacteria in immunocompetent hosts with H. pylori infection.

- Citation: Chung HA, Lee SY, Moon HW, Kim JH, Sung IK, Park HS, Shim CS, Han HS. Does the antibody production ability affect the serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG titer? World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2016; 7(3): 288-295

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v7/i3/288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v7.i3.288

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection triggers inflammatory and immune responses[1,2]. The serum anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer is affected by various factors, including bacterial colonization, persistence, virulence, and host immune responses[3,4]. However, the persistence of H. pylori over decades in infected individuals suggests that the anti-H. pylori IgG does not play a role in the host immune response.

Serum antibody titers depend on the ability of individuals to produce antibodies. It is known that in Koreans, serum titers of the surface antibody against the hepatitis B virus (HBsAb) vary after hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccinations[5]. Approximately 10% of Koreans do not develop an adequate immune response after they have received a vaccination series, and the rate of non-responsiveness correlates with older age, smoking, male gender, and the presence of chronic diseases[6,7]. Similarly, variable anti-H. pylori IgG titers may reflect different immune statuses in individuals with a similar H. pylori burden. Taken together with an established link between the HBV vaccine response and immune constitution[8,9], these findings suggest that the evaluation of the HBsAb response in HBV-vaccinated individuals could provide useful information regarding their immune states.

The immune response via the activation of helper T cells may stimulate production of both the H. pylori IgG and HBsAb[2,8], although the theoretical background underlying this mechanism remains uncertain. Little is known about the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer as a parameter of the immune response to H. pylori infection because the knowledge of the H. pylori immunopathogenesis is limited. In addition, it is unclear whether the beneficial functional immune aspects inherent in vaccine responders can be translated into a robust immune response after H. pylori infection.

In the present study, gastric biopsy samples were analyzed to determine whether there is a correlation between the serum titers of the anti-H. pylori IgG and HBsAb in conditions with a similar H. pylori burden. In addition, variables that significantly correlated with the serum titers of the anti-H. pylori IgG and HBsAb were analyzed.

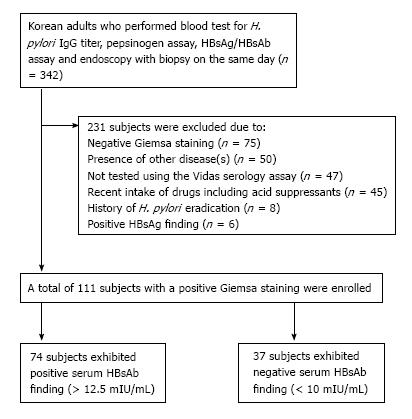

In this cross-sectional study, Korean adults who underwent upper esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with gastric biopsies for pathology and Giemsa staining, serum pepsinogen (PG) assay, serum anti-H. pylori IgG assay and serum HBV surface antigen (HBsAg)/HBsAb assay on the same day at our center were included (Figure 1). The subjects were excluded in following conditions: (1) negative Giemsa staining; (2) positive HBsAg finding; (3) recent medication; (4) history of H. pylori eradication; (5) serum anti-H. pylori IgG testing other than the Vidas assay; or (6) the presence of disease(s) including any condition related to immunosuppressed state. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ID: KCT0001302 (https://cris.nih.go.kr) after the approval by the institutional review board of the Konkuk University School of Medicine (KUH1010625).

Venous blood was sampled after 12 h of fasting for serum anti-H. pylori IgG assay, serum PG assay and serum HBsAg/HBsAb assay. The H. pylori serology titer was measured using the Vidas H. pylori IgG assay (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Based on the Vidas H. pylori IgG assay package insert, positive finding was defined as a serum IgG titer equal or over 1.00 with sensitivity of 98.1% and specificity of 90.8%.

For serum PG I and PG II concentrations, the fasting blood samples were centrifuged and measured using the latex-enhanced turbidimetic immunoassay (HBi

Co., Anyang, South Korea)[10]. Gastric corpus atrophy was diagnosed if the serum PG I/II ratio was less than 3.0 and the serum PG I concentration was less than 70 ng/mL.

Fasting blood sample was analyzed for the serum HBsAg and HBsAb levels using the ADVIA Centaur system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Deerfield, IL, United States) as described in the previous study[11]. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, negative findings were provided if the index value of HBsAg was of < 1.0 and if HBsAb was of < 7.5 mIU/mL on this chemiluminescent immunoassay. For HBsAg, equivocal findings were provided if the index value was equal to 1.0, while positive findings were provided if it was of > 1.0. For HBsAb, equivocal findings were provided if the index value was between 7.5 and 12.5 mIU/mL, while positive findings were provided if it was of > 12.5 mIU/mL.

Each participant underwent EGD on the same day of blood sampling at our center using GIF-H260 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) endoscope. During EGD, gastric biopsy was performed for pathology, histologic assay of H. pylori density and Giemsa staining. The biopsied specimens were fixed in 95% ethanol and embedded in paraffin blocks. Thereafter, the samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Giemsa. Histologic assay of H. pylori density were graded as mild, moderate and marked infiltration. If the density differed according to the biopsied site, the highest density and location were collected for the statistical analysis. Based on the Updated Sydney System, the grades were scored as either none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or marked (3) for activity (the intensity of acute polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates), inflammation (the intensity of chronic mononuclear cell infiltrates), atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia.

A first-line therapy was performed with amoxicillin 1 g, clarithromycin 500 mg, and a proton pump inhibitor 20 mg twice daily to the subjects who agreed on H. pylori eradication. Four weeks after the eradication, a urease breath test was carried out. If it was positive, a second-line therapy was performed with tetracycline 500 mg, bismuth 300 mg four times a day, metronidazole 500 mg and a proton pump inhibitor twice a day. Follow-up tests for EGD and serum assays were performed as the initial tests described above.

For the statistical analysis, SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) were used. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD using the Student’s t-test, while categorical variables were summarized as frequency (%) using the χ2 test. The differences between the groups were compared using the ANOVA test for continuous variables.

The strength of correlation between the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer and variables were estimated by correlation analysis. For continuous variables that were found to be related to severe H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed by plotting sensitivity (true-positive rate) against 1-specificity (false-positive rate). Accuracies of the significant variables were measured based on the area under the ROC curve (AUC) analysis with a 95%CI and standard error (SE) values.

Follow-up data were analyzed to compare the changes between the subjects with successful eradication and those with persistent H. pylori infection. For the eradicated subjects, differences between pre- and post-eradication were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. In similar, differences between initial and follow-up data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test in the subjects with persistent H. pylori infection.

A total of 111 Korean adults were tested with the Vidas assay, and 74 (66.7%) subjects exhibited a positive HBsAb finding. The degrees of H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy were mild in 14 subjects, moderate in 23 subjects, and marked in 74 subjects (Table 1). The serum HBsAb findings did not differ between the groups (Table 2). Of all variables, marked degree of H. pylori infiltration showed the highest serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer (P < 0.001) and serum PG II concentration (P = 0.021).

| Variables | Subjects (n = 111) |

| Age (years old, mean ± SD) | 55.3 ± 9.7 |

| Gender (male:female) | 66:45 |

| Serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer (AU/mL, mean ± SD) | 3.26 ± 0.97 |

| Serum PG I level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 72.0 ± 28.8 |

| Serum PG II level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 22.0 ± 9.2 |

| Serum PG ratio (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.2 |

| Presence of corpus gastric atrophy as reflected by serum PG assay | 23 (20.7) |

| Degree of H. pylori infiltration on biopsy | |

| Mild | 14 (12.6) |

| Moderate | 23 (20.7) |

| Marked | 74 (66.7) |

| Scores based on Updated Sydney system | |

| Activity (mean ± SD) | 1.92 ± 0.69 |

| Chronic inflammation (mean ± SD) | 2.04 ± 0.38 |

| Atrophy (median with ranges) | 0.97 (0-3) |

| Intestinal metaplasia (median with ranges) | 0.64 (0-3) |

| Biopsied site | |

| Antrum | 69 (62.2) |

| Body or angle | 36 (32.4) |

| Fundus or cardia | 6 (5.4) |

| Serum HBsAb titer (mIU/mL, median with ranges) | 102.19 (1-1000) |

| Positive HBsAb assay | 78 (70.3) |

| Platelet (× 103/μL, mean ± SD) | 235.3 ± 48.2 |

| White blood cell count (× 103/μL, mean ± SD) | 5853.8 ± 1595.9 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 56.0 ± 9.3 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 36.4 ± 8.7 |

| Monocyte (%) | 4.7 ± 1.6 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 1.84 (0-13) |

| Basophil (%) | 0.41 (0-5) |

| Variables | Mild H. pylori infiltration (n = 14) | Moderate H. pylori infiltration (n = 23) | Marked H. pylori infiltration (n = 74) | P value |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 54.7 ± 8.4 | 57.7 ± 12.0 | 54.7 ± 9.0 | 0.428 |

| Gender (male) | 6 (42.9) | 16 (69.6) | 44 (59.5) | 0.276 |

| Serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer (AU/mL)1 | 2.39 (0.36-4.00) | 3.37 (1.86-4.00) | 3.95 (0.82-4.00) | < 0.001 |

| Serum PG I level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 58.0 ± 19.3 | 75.5 ± 32.6 | 73.6 ± 28.7 | 0.146 |

| Serum PG II level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 15.6 ± 6.3 | 22.9 ± 9.5 | 22.9 ± 9.2 | 0.021 |

| Serum PG I/II ratio (mean ± SD) | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 0.118 |

| Presence of corpus gastric atrophy as reflected by PG assay | 3 (21.4) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (20.3) | 0.986 |

| Biopsied site (antrum:body or angle:fundus or cardia) | 1:3:0 | 15:7:1 | 43:26:5 | 0.625 |

| Scores based on Updated Sydney system | ||||

| Activity (mean ± SD) | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 0.034 |

| Inflammation (mean ± SD) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.052 |

| Atrophy (median with ranges) | 0.8 (0-3) | 1.3 (0-3) | 0.9 (0-3) | 0.589 |

| Intestinal metaplasia (median with ranges) | 0.6 (0-3) | 0.9 (0-3) | 0.6 (0-3) | 0.771 |

| Positive HBsAb finding | 9 (64.3) | 17 (73.9) | 52 (70.3) | 0.824 |

| HBsAb titer (mIU/mL)1 | 174.9 (1-1000) | 120.7 (1-1000) | 86.8 (1-1000) | 0.601 |

| Platelet (× 103/μL, mean ± SD) | 252.2 ± 41.9 | 231.9 ± 51.9 | 233.2 ± 48.1 | 0.375 |

| White blood cell count (× 103/μL, mean ± SD) | 5688.6 ± 1552.3 | 5780.0 ± 1390.9 | 5908.0 ± 1678.0 | 0.869 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 55.1 ± 9.3 | 54.9 ± 10.3 | 45.5 ± 9.1 | 0.702 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 36.8 ± 8.7 | 37.0 ± 9.8 | 36.2 ± 8.4 | 0.919 |

| Monocyte (%) | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 0.732 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 2.4 (0-6) | 2.0 (0-1) | 1.8 (0-1) | 0.819 |

| Basophil (%) | 0.4 (0-1) | 0.5 (0-1) | 0.4 (0-5) | 0.771 |

There was no significant correlation between serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer and serum HBsAb titer (P = 0.557). The serum HBsAb titer was not related to any of the tested variables including the counts of platelet and white blood cell (Table 3).

| Variables | Correlation coefficient | P value |

| Serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer | ||

| Old age | -0.009 | 0.924 |

| Increased density of H. pylori infiltration | 0.389 | < 0.001 |

| Increased serum PG I level | 0.116 | 0.224 |

| Increased serum PG II level | 0.194 | 0.042 |

| Increased serum PG I/II ratio | -0.18 | 0.059 |

| Higher degree of activity | 0.272 | 0.004 |

| Higher degree of inflammation | 0.125 | 0.192 |

| Higher degree of atrophy | 0.021 | 0.826 |

| Higher degree of intestinal metaplasia | -0.047 | 0.624 |

| Presence of gastric corpus atrophy as reflected by PG assay | -0.015 | 0.876 |

| Increased HBsAb titer | -0.056 | 0.557 |

| Increased platelet count | -0.061 | 0.522 |

| Increased white blood cell count | -0.078 | 0.417 |

| Serum HBsAb titer | ||

| Old age | -0.088 | 0.358 |

| Increased density of H. pylori infiltration | -0.07 | 0.466 |

| Increased serum PG I level | 0.046 | 0.634 |

| Increased serum PG II level | -0.054 | 0.572 |

| Increased serum PG I/II ratio | 0.136 | 0.154 |

| Higher degree of activity | 0.077 | 0.42 |

| Higher degree of inflammation | -0.112 | 0.24 |

| Higher degree of atrophy | 0.036 | 0.706 |

| Higher degree of intestinal metaplasia | 0.054 | 0.573 |

| Presence of gastric corpus atrophy as reflected by PG assay | -0.164 | 0.086 |

| Increased platelet count | 0.008 | 0.935 |

| Increased white blood cell count | -0.069 | 0.473 |

The serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer was positively correlated with the density of H. pylori infiltration on gastric biopsy (P < 0.001) and the serum PG II concentrations (P = 0.042) using the correlation analysis. However, it was neither related to the positive HBsAb finding (P = 0.905) nor the serum HBsAb titer (P = 0.557). Distribution of serum anti-H. pylori IgG titers according to the H. pylori infiltration are shown in Figure 2.

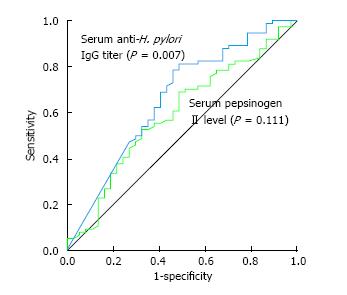

Significant variables for H. pylori infiltration were analyzed using the ROC curve analysis (Figure 3). The cut-off value of serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer for correlating with severe density of H. pylori infiltration was 2.9 AU/mL with sensitivity and specificity values 81.1% and 51.4% (AUC = 0.659, 95%CI: 0.548-0.770, SE = 0.057, P = 0.007). However, serum PG II concentration showed no statistical significance (AUC = 0.593, 95%CI: 0.481-0.705, SE = 0.057, P = 0.111) on the ROC analysis.

Of 111 included subjects, 41 were followed up for EGD and serum assays. Of these 41 followed-up subjects, 29 underwent H. pylori eradication therapy, and 4 failed on eradication. Therefore, a comparison was made between 25 subjects with successful eradication and 16 subjects with persistent infection (including 4 who failed on eradication). There was no difference on the initial test findings between the eradicated and persistent groups (Table 4).

| Successful H. pylori eradication (n = 25) | Persistent H. pylori infection (n = 16) | P value | Before eradication | After eradication | P value (Z1) | Initial | Follow-up | P value | |

| Initial test findings | |||||||||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 52.3 ± 7.9 | 55.3 ± 12.7 | 0.351 | ||||||

| Gender (male:female) | 15:10 | 9:07 | 1 | ||||||

| Degree of H. pylori infiltration on biopsy (mild:moderate: marked) | 4:05:16 | 2:04:10 | 0.907 | ||||||

| Anti-H. pylori IgG titer (AU/ mL, mean ± SD) | 3.00 ± 1.17 | 3.17 ± 0.92 | 0.632 | ||||||

| PG I level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 79.3 ± 31.7 | 64.9 ± 23.4 | 0.126 | ||||||

| PG II level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 23.4 ± 8.5 | 18.9 ± 9.1 | 0.117 | ||||||

| PG ratio (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 0.419 | ||||||

| Presence of corpus gastric atrophy as reflected by serum PG assay | 4 (16.0) | 2 (12.5) | 0.566 | ||||||

| HBsAb titer (mIU/mL, median with ranges) | 72.2 (3.1-1000) | 170.3 (3.1-1000) | 0.632 | ||||||

| Positive HBsAb assay | 16 (64) | 12 (75) | 0.513 | ||||||

| Duration of the follow-up period (months, median with ranges) | 18.1 (2-61) | 20.2 (6-41) | 0.887 | ||||||

| Subjects with successful H. pylori eradication (n = 25) | |||||||||

| Follow-up test findings | |||||||||

| Degree of H. pylori infiltration on biopsy (none:mild:moderate: marked) | 0:4:5:16 | 25:0:0:0 | < 0.001 (-4.520) | ||||||

| Anti-H. pylori IgG assay (negative:lowest:middle:highest quartiles)2 | 3:2:14:6 | 20:4:1:0 | < 0.001 (-4.171) | ||||||

| PG I level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 79.3 ± 31.7 | 54.2 ± 14.5 | 0.028 (-2.201) | ||||||

| PG II level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 23.4 ± 8.5 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 0.028 (-2.201) | ||||||

| PG ratio (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 1.6 | 0.028 (-2.200) | ||||||

| HBsAb titer (mIU/mL, median with ranges) | 72.5 (3.1-1000) | 18.4 (3.1-1000) | 0.308 | ||||||

| Subjects with persistent H. pylori infection (n = 16) | |||||||||

| Follow-up test findings | |||||||||

| Degree of H. pylori infiltration on biopsy (none:mild:moderate: marked) | 0:2:4:10 | 1:3:2:10 | 0.335 | ||||||

| Anti-H. pylori IgG assay (negative:lowest:middle:highest quartiles)2 | 1:0:8:7 | 0:2:7:7 | 1.18 | ||||||

| PG I level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 64.9 ± 23.4 | 71.8 ± 35.2 | 1 | ||||||

| PG II level (ng/mL, mean ± SD) | 18.9 ± 9.1 | 21.4 ± 10.3 | 0.779 | ||||||

| PG ratio (mean ± SD) | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 0.395 | ||||||

| HBsAb titer (mIU/mL, median with ranges) | 170.3 (3.1-1000) | 202.1 (3.1-1000) | 0.314 | ||||||

After H. pylori eradication, significant decreases were noticed on the degree of H. pylori infiltration (P < 0.001), serum PG I concentration (P = 0.028) and serum PG II concentration (P = 0.028). As a consequence, the serum PG I/II ratio was significantly increased after eradication (P = 0.028). On the contrary, there was no significant differences between the initial and follow-up data on H. pylori infiltration (P = 0.335) and serum PG I/II ratio (P = 0.395) in the subjects with persistent H. pylori infection.

A significant link has been found between the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer and the bacterial load of the stomach, regardless of the antibody producing capability of the host. Furthermore, significant decreases of the degree of H. pylori infiltration, serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer, and serum concentrations of PG I and PG II in the subjects with successfully eradicated H. pylori infection were observed. At the same time, such changes were not observed in the subjects with persistent H. pylori infection. Based on these results, the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer could be considered an indicator of the bacterial burden in infected subjects. This finding may lead to novel opportunities toward enhancing H. pylori eradication.

H. pylori has the ability to persist despite a vast array of host immune responses, which appear to differ between infected subjects[12]. The present findings suggest that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer is related to the burden of H. pylori antigens, because lymphocytes are sensitized to the H. pylori antigens and IgG is produced by B cells against a variety of H. pylori surface (flagellar) proteins and bacterial toxins. Furthermore, the development of the positive HBV vaccine antibody response involves not only the T cell functions, but also other functional pathways, including B cell activity and antigen presentation of the peptide-based vaccine[6,7,13]. These findings suggest that the amount of IgG production via the host immune response upon H. pylori infection is more closely related to the burden of H. pylori antigens than to the ability of the host to produce antibodies, which is gauged by the serum HBsAb titer.

In the present study, it was found that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer positively correlated with the degree of H. pylori infiltration on the biopsied specimen, regardless of the biopsied site of the stomach. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies, in which the significance of the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer was demonstrated, and indirectly indicates the relationship between the severity of histological changes and mucosal bacterial density[14-16]. Evaluation of the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer can detect H. pylori infection in patients with marked atrophic gastritis and metaplastic gastritis, even in the event of negative biopsy specimens, and provide an indicator of the efficacy of H. pylori eradication[17-20].

Serum PG assays are widely used for the measurements of gastric inflammation[21,22] and in combination with the serum anti-H. pylori IgG assay during gastric cancer screening[10,23]. The link between the immune response and H. pylori infection-induced gastric inflammation, as measured by the serum PG assay, has been established[24]. In that study, the Salmonella typhi (S. typhi) IgG seroconversion was more common in the subjects with the H. pylori infection than in those without it after anti-S. typhi vaccination. In the present study, the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer positively correlated with the serum PG levels and H. pylori infiltration in biopsy samples, regardless of the HBsAb titer. This suggests that the bacterial burden directly correlates with the degree of gastric inflammation, despite the differential development and recruitment of specifically committed cells that occurred after the H. pylori infection in the subjects.

The limitation of this study is that only 41 subjects underwent the follow-up tests. Furthermore, the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer was followed up using the Chorus H. pylori IgG assay (DIESSE Diagnostica Senese, Siena, Italy) because the initially used Vidas H. pylori IgG assay was not available after 2012. Despite these limitations, significant differences in the follow-up findings of serum assays and H. pylori infiltration were found only in the subjects in whom H. pylori eradication was successfully achieved. In support of these observations, a recent study described a high rate of concurrence and similar diagnostic accuracy between the Vidas H. pylori IgG assay and the Chorus H. pylori IgG assay[25].

In conclusion, the findings of this study show that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer is significantly associated with the bacterial load of the stomach, regardless of the antibody producing capability of the host. Although the anti-H. pylori IgG response requires preserved function of several immune pathways, it appears that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer correlates with the intragastric bacterial load rather than with the HBsAb titer. The serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer is therefore useful for estimating the bacterial burden of H. pylori infection.

Serum antibody titers depend on the ability of individuals to produce antibodies. It is unclear whether the beneficial functional immune aspects inherent in hepatitis B virus vaccine responders can be translated into a robust immune response after Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

In this cross-sectional study, consecutive Korean adults were included whose samples had positive Giemsa staining on endoscopic biopsy and were studied in the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg)/HBsAb serologic assay, pepsinogen (PG) assay, and anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) assay on the same day. This approach allows the authors to demonstrate correlation between serum HBsAb titer and anti-H. pylori IgG titer.

In this study the authors demonstrated that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer correlates with the intragastric bacterial load rather than with the HBsAb titer.

The serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer is therefore useful for estimating the bacterial burden of H. pylori infection.

Serologic testing for IgG antibodies to H. pylori is commonly used noninvasive method to diagnose H. pylori infection. The IgG antibody titer is indicative of the severity of gastritis and the presence of H. pylori.

This is a novel look at a very interesting topic. In the clinical finding presented in this manuscript, the authors showed that the serum anti-H. pylori IgG assay can be used to estimate the burden of bacteria in immunocompetent hosts with H. pylori infection.

| 1. | McNamara D, El-Omar E. Helicobacter pylori infection and the pathogenesis of gastric cancer: a paradigm for host-bacterial interactions. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:504-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wilson KT, Crabtree JE. Immunology of Helicobacter pylori: insights into the failure of the immune response and perspectives on vaccine studies. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:288-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Portal-Celhay C, Perez-Perez GI. Immune responses to Helicobacter pylori colonization: mechanisms and clinical outcomes. Clin Sci (Lond). 2006;110:305-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Robinson K, Kenefeck R, Pidgeon EL, Shakib S, Patel S, Polson RJ, Zaitoun AM, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcer disease is associated with inadequate regulatory T cell responses. Gut. 2008;57:1375-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yeo Y, Gwack J, Kang S, Koo B, Jung SJ, Dhamala P, Ko KP, Lim YK, Yoo KY. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer in Korea: an epidemiological perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6227-6231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wiedmann M, Liebert UG, Oesen U, Porst H, Wiese M, Schroeder S, Halm U, Mössner J, Berr F. Decreased immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2000;31:230-234. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Altunöz ME, Senateş E, Yeşil A, Calhan T, Ovünç AO. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have a lower response rate to HBV vaccination compared to controls. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1039-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Yoon JH, Shin S, In Jw, Chang JY, Song EY, Roh EY. Association of HLA alleles with the responsiveness to hepatitis B virus vaccination in Korean infants. Vaccine. 2014;32:5638-5644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martinetti M, De Silvestri A, Belloni C, Pasi A, Tinelli C, Pistorio A, Salvaneschi L, Rondini G, Avanzini MA, Cuccia M. Humoral response to recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine at birth: role of HLA and beyond. Clin Immunol. 2000;97:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choi HS, Lee SY, Kim JH, Sung IK, Park HS, Shim CS, Jin CJ. Combining the serum pepsinogen level and Helicobacter pylori antibody test for predicting the histology of gastric neoplasm. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim H, Hur M, Moon HW, Park CM, Cho JH, Park KS, Lee K, Chang S. Pre- and post-transfusion testing for hepatitis B virus surface antigen and antibody in blood recipients: a single-institution experience in an area of high endemicity. Ann Lab Med. 2012;32:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Genta RM. The immunobiology of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:2-11. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Goncalves L, Albarran B, Salmen S, Borges L, Fields H, Montes H, Soyano A, Diaz Y, Berrueta L. The nonresponse to hepatitis B vaccination is associated with impaired lymphocyte activation. Virology. 2004;326:20-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tu H, Sun L, Dong X, Gong Y, Xu Q, Jing J, Yuan Y. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G titer correlates with grade of histological gastritis, mucosal bacterial density, and levels of serum biomarkers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sheu BS, Shiesh SC, Yang HB, Su IJ, Chen CY, Lin XZ. Implications of Helicobacter pylori serological titer for the histological severity of antral gastritis. Endoscopy. 1997;29:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gong YH, Sun LP, Jin SG, Yuan Y. Comparative study of serology and histology based detection of Helicobacter pylori infections: a large population-based study of 7,241 subjects from China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:907-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Imaizumi H, Hibi K, Kida M, Ohida M, Okayasu I, Saigenji K. Effect of anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody titer following eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:293-296. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Fanti L, Ieri R, Mezzi G, Testoni PA, Passaretti S, Guslandi M. Long-term follow-up and serologic assessment after triple therapy with omeprazole or lansoprazole of Helicobacter-associated duodenal ulcer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:45-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marchildon P, Balaban DH, Sue M, Charles C, Doobay R, Passaretti N, Peacock J, Marshall BJ, Peura DA. Usefulness of serological IgG antibody determinations for confirming eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2105-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hirschl AM, Brandstätter G, Dragosics B, Hentschel E, Kundi M, Rotter ML, Schütze K, Taufer M. Kinetics of specific IgG antibodies for monitoring the effect of anti-Helicobacter pylori chemotherapy. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:763-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun LP, Gong YH, Wang L, Yuan Y. Serum pepsinogen levels and their influencing factors: a population-based study in 6990 Chinese from North China. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6562-6567. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Shiota S, Murakami K, Okimoto T, Kodama M, Yamaoka Y. Serum Helicobacter pylori CagA antibody titer as a useful marker for advanced inflammation in the stomach in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kishikawa H, Nishida J, Ichikawa H, Kaida S, Takarabe S, Matsukubo T, Miura S, Morishita T, Hibi T. Fasting gastric pH of Japanese subjects stratified by IgG concentration against Helicobacter pylori and pepsinogen status. Helicobacter. 2011;16:427-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Muhsen K, Pasetti MF, Reymann MK, Graham DY, Levine MM. Helicobacter pylori infection affects immune responses following vaccination of typhoid-naive U.S. adults with attenuated Salmonella typhi oral vaccine CVD 908-htrA. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1452-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee SY, Moon HW, Hur M, Yun YM. Validation of western Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody assays in Korean adults. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Slomiany BL S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ