Published online Nov 15, 2014. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i4.487

Revised: March 27, 2014

Accepted: July 17, 2014

Published online: November 15, 2014

Processing time: 317 Days and 5 Hours

Rectovaginal fistula is a disastrous complication of Crohn’s disease (CD) that is exceedingly difficult to treat. It is a disabling condition that negatively impacts a women’s quality of life. Successful management is possible only after accurate and complete assessment of the entire gastrointestinal tract has been performed. Current treatment algorithms range from observation to medical management to the need for surgical intervention. A wide variety of success rates have been reported for all management options. The choice of surgical repair methods depends on various fistula and patient characteristics. Before treatment is undertaken, establishing reasonable goals and expectations of therapy is essential for both the patient and surgeon. This article aims to highlight the various surgical techniques and their outcomes for repair of CD associated rectovaginal fistula.

Core tip: Rectovaginal fistula secondary to Crohn’s disease is a devastating and disabling condition with a significant negative impact on quality of life. Furthermore, these fistulae pose an extremely challenging dilemma for the clinician with unique and often frustrating management challenges. Medical management is often futile and surgery may offer the only chance for cure. In this article, we aim to review the various treatment options to close these difficult to treat fistulae, with an emphasis on surgical technique and complex decision making.

- Citation: Valente MA, Hull TL. Contemporary surgical management of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5(4): 487-495

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v5/i4/487.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v5.i4.487

Fistula-in-ano is the most common perianal manifestation of Crohn’s disease (CD) and was first reported by Gabriel[1] in 1921, nine years before Crohn et al[2] identified regional enteritis as a clinical entity. These fistulae are classified by their relationship to the sphincter complex as either high (supra- or extra-sphincteric vs low (inter- or trans-sphincteric). Low fistulae that transverse the anal sphincter are more appropriately named anovaginal fistulae, but by convention, all such fistulae are termed rectovaginal fistula (RVF). After obstetrical trauma, CD is the most common etiological factor for RVF, and will occur in up to 10% of women with CD[3,4].

Rectovaginal fistulae secondary to CD are associated with significant morbidity and carry an increased risk for proctectomy[5,6]. It is a devastating and disabling condition and is a source of considerable social embarrassment and has a significant negative impact on quality of life. Furthermore, CD associated RVF are an extremely challenging dilemma for the clinician and present unique and often frustrating management challenges. In this article, we aim to review the various treatment options to close these difficult to treat fistulae, with an emphasis on surgical technique and decision making.

The presence of a fistulous tract between the gastrointestinal tract and the vagina can be distressing and embarrassing for the patient. The most common symptoms includes passage of either gas and/or stool via the vagina. Women may also report purulence from the vagina, dyspareunia, perineal pain and tenderness, along with vaginal irritation and recurrent genitourinary tract infections[3,7]. Physical examination may demonstrate the fistulous opening on inspection of the lower anorectum and vagina, but often, the RVF is not visible on inspection. The clinician must have a high index of suspicion when a women presents with signs and symptoms consistent with a RVF. These patients are best evaluated with an examination under anesthesia for definitive elucidation of the RVF[3].

Several other studies are available to help identify and delineate RVF including computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fistulography, and endoluminal ultrasound (EUS). The use of EUS with hydrogen peroxide enhancement has been advocated in the evaluation of complex fistula disease to visualize side tracts and areas of fluid collection[3,8-10]. Sloots et al[10] reported on this modality in 41 patients with CD related fistula-in-ano (32% with RVF), and found that 78% of the patients had a more complex fistula found during EUS. An added benefit of using EUS to evaluate the fistula tract, is the ability to identify any anal sphincter defects.

After a comprehensive workup and evaluation of the perineum, the remainder of the small and large bowel, rectum, and anal canal must be investigated. It is important to identify any other active areas of CD in order to plan both medical and potential surgical management. Work-up may include a colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, small bowel series, CT or MRI enterography. If proximal CD is found, optimization with medical and/or surgical management should be strongly considered before any attempt to repair the RVF.

There are several disease characteristics that guide treatment recommendations for patients with RVF. These include the location of the fistula (high, low, or transsphincteric), anal canal disease (ulcerations or stricturing), the presence of active inflammation in the rectum, and rectal compliance. The presence and severity of symptoms, discomfort, and quality of life also weigh heavily in regards to treatment type and timing. Because there is considerable debate with regards to the best treatment options for these notoriously difficult to close fistulae, a frank discussion setting realistic goals and expectations of treatment is the initial step. Patients with no or minimal symptoms may actually be advised to have no treatment at all[7,11-12]. For patients with intolerable symptoms, a logical and stepwise approach to management begins with conservative medical therapy and advances to surgical intervention when indicated[3]. It should be noted that there are currently no prospective, randomized, controlled trials for the surgical correction of CD related RVF. The factors previously discussed along with personal experience, surgical judgment and a critical appraisal of the available literature should be used to formulate an optimal and tailored treatment plan for women with CD associated RVF[3].

Traditionally treatment of CD associated RVF has been mostly surgical as medical treatments were fraught with failure[3]. Medical treatment has centered on pharmacological therapy aimed at alleviating and treating the underlying active CD along with medication to alter stool consistency and control diarrhea. Current medications targeting CD include antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics. Metronidazole has been reported to successfully treat RVF, although most surgeons will use this and other antibiotics as an adjunct to surgical treatment[3,13]. Present et al[14-16] have written extensively on various medical modalities for the treatment of all types of CD related fistulae, including, cyclosporine, 6-mercatopurine, and infliximab. A randomized, double-blinded, multicenter study by Present et al[16] studied infliximab for the treatment of both abdominal and perianal fistulae from CD. After 18 wk of infliximab treatment the authors found significant reduction in the number of fistulae with complete closure occurring in 46% vs 13% of placebo. The follow-up was relatively short (4.5 mo) and the study included all enterocutaneous fistulae, not specifically RVF, making generalizability to RVF somewhat limited.

In the ACCENT II study by Sands et al[17], the authors evaluated the effect of infliximab in patients with RVF secondary to CD. Twenty-five patients were enrolled and received infliximab infusions at weeks zero, two, and six. Initial responders (those who showed a 50% reduction in their fistula in the first ten weeks) were then randomized to continue receiving infliximab or placebo. At 54 wk follow-up, 44% of the initial responders healed their fistulae and alternatively 56% had RVF recurrence, regardless of infliximab treatment. Essentially, the women who initially responded to the infliximab had a 50% chance of fully healing their RVF.

It is unclear which RVF will respond to infliximab nor is there evidence that infliximab will reduce fistula recurrence rates. At our institution we tend to recommend infliximab (or other biologic therapy) as initial treatment when surrounding tissues are inflamed or ulcerated such that any attempt at surgical closure will uniformly fail. In some patients, the RVF may close with this therapy, but if it persists and the active inflammation becomes quiescent, then surgical correction may be attempted.

Local repair of RVF secondary to CD can be successfully accomplished when optimal conditions exist. The approaches to local repair include transperineal, transvaginal, and transanal (with or without transabdominal mobilization) techniques. The choice of technique depends on the experience of the surgeon, location of the RVF, and the status and extent of local and distant inflammatory bowel disease activity. Additionally, anal sphincter integrity in women after vaginal delivery must be considered as some patients may require a sphincter repair along with the fistula repair.

An important aspect of RVF repair is initial drainage of perianal sepsis before consideration of surgical closure. Often, the use of loose draining setons is required for adequate sepsis control. The addition of antibiotics may also benefit selected patients with significant purulence. There is a group of women that benefit from a diverting stoma to facilitate sepsis eradication. Typically a stoma is helpful if stool consistency is loose and/or frequent. An added benefit of the stoma procedure is that is allows surgical treatment of intestinal CD at the same operation. Consideration of each of these steps is mandatory before any definitive attempt at RVF repair is undertaken. A waiting period of at least 3-6 mo is needed for all local inflammation and infection to be cleared.

It should be noted that in women with active anorectal disease, the use of a draining seton may be used indefinitely as a sphincter-saving procedure. Seton use in this situation has been shown to successfully preserve fecal continence and delay or avoid a permanent stoma in those women who cannot undergo local surgical repair[3,7,18,19].

Low and superficial (anovaginal) fistulas can be layed open or excised with a simple fistulotomy in very few select cases with successful healing. These circumstances are rare and virtually no sphincter muscle must be involved for this technique to be considered. If there is any anal canal deformity after fistulotomy (keyhole deformity), some degree of fecal incontinence will undoubtedly result[3,7].

The anocutaneous flap technique is rarely utilized but may be considered in situations where anal stenosis is present. The technique consists of mobilizing an island of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the anal margin or verge and advancing this flap into the anal canal to cover the RVF. This procedure is only possible if the anal skin is soft and pliable, which is not common in perianal CD patients. Hesterberg et al[20] reported a 70% healing rate at median follow-up of 18 mo with this technique.

Most authors believe that repairing RVF from the high pressure (rectal) side of these low pressure fistulas is advantageous. This allows for the source of the fistula to be excised and closed. Then a healthy layer of tissue (flap) is used to cover the repair[7,21,22]. There is a wide variety of flap configurations, but the standard curvilinear rectal advancement flap is the most commonly performed flap procedure for RVF.

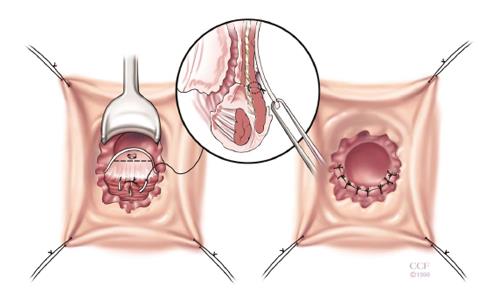

The rectal advancement flap (RAF) repair has been somewhat successful in healing RVF secondary to CD and should be considered in women with favorable anorectal anatomy[3]. Patients with minimally diseased or normal rectum and a normal anal canal are ideal candidates for this type of repair. However, this technique is contraindicated in women with extensive ulceration or stricturing of the anal canal and transitional zone as well as women with an anterior sphincter defect[3]. It should also be used with caution in woman with fecal incontinence. The technique has been well described in the literature, but briefly, it consists of making a curvilinear incision nearly 180 degrees just distal to the fistula opening in the anal canal. The mucosa of the cephalad anal canal is removed and then a flap of mucosa, submucosa and the rectal wall is dissected from the rectovaginal septum cephalad for approximately 4-5 cm. After sufficient mobilization to avoid tension when advancing the flap, that fistula is cored out and the fistula opening closed with absorbable suture. The flap is then trimmed and advanced distally to the cut edge. Then using absorbable sutures it is sewn to this cut edge with deep bites. The vaginal or perineal external opening is left open for drainage (Figure 1).

Hull and Fazio[23] reviewed forty-eight women who had an anovaginal fistula secondary to CD, with 35 undergoing one of 3 types of flap repairs. Twenty-four women underwent RAF with the standard curvilinear incision and six patients with a long and high RVF or the presence of anal ulceration, underwent a linear flap procedure. The initial healing rate of all repair types was 54%, with an ultimate healing rate of 68% after additional surgical procedures were performed. The authors concluded that surgical intervention for low RVF secondary CD is advocated in properly selected patients by using an individualized approach based on the nature of the anovaginal fistula.

In another study by Kodner et al[24], endorectal advancement flaps were created in 24 patients with CD and a relatively normal rectum. Seventeen out of twenty-four (71%) patients achieved primary healing after initial flap repair and a total of 22/24 patients had healing after further repairs. Similarly, Makowiec et al[25] and Crim et al[26] reported successful healing of RVF secondary to CD in 5/12 and 10/14 patients, respectively with this technique.

Ruffolo et al[27] stress that the advantages of a flap procedures are a low chance of: producing a keyhole deformity, worsening fecal incontinence, or aggravation of patient’s symptoms in case of failure. Additionally, there is no perineal wound and the presence of a stoma is not mandatory.

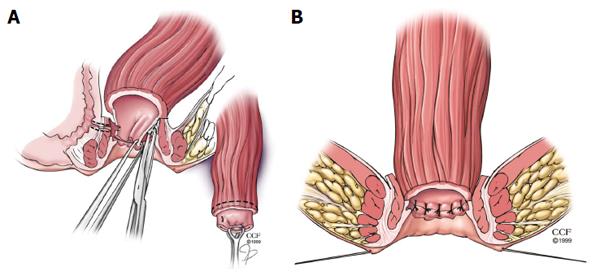

When an endorectal advancement flap is not an acceptable choice for RVF repair due to extensive ulceration or stricturing in the anal canal and transition zone, the rectal sleeve advancement flap may be considered. This technique also requires a normal or near normal rectum. First reported in the literature by Berman in 1991, the rectal sleeve advancement flap removes all of the diseased tissue in the anal canal and allows for a more ‘normal’ sleeve of rectal tissue to be sutured to the neodentate line[3,28,29]. The rectum should also be distensible and not exhibit any significant scarring from quiescent Crohn’s proctitis. Starting at the dentate line, a mucosectomy of the ulcerated mucosa and submucosa of the anal canal is performed. The mobilization is 90%-100% circumferentially. Next the dissection breaches into the supralevator space and the rectal mobilization is continued cephalad until sufficient mobility is achieved so the rectum can be advanced within the sleeve of the internal sphincter to the neodentate line without tension. Anteriorly the dissection is in the rectovaginal septum. The fistula tract is then cored out and sutured, leaving the vaginal mucosa open as was discussed in the RAF (Figure 2A). The diseased distal margin of tissue is trimmed, and the cuff of rectum is advanced down and sutured to the ridge of anoderm, again using absorbable sutures as was described for the RAF (Figure 2B)[23]. In the event that sufficient mobility cannot be obtained to bring the sleeve of tissue to the cut distal edge without tension, the patient and the surgeon must be prepared to convert the operation to a transabdominal approach, with full mobilization of rectum, descending colon, and splenic flexure. Additionally, if a tension -free anastomosis cannot be achieved, proctectomy with end stoma may be necessary so the patient must be appraised of this possibility during the informed consent[3].

In a study from our institution, Marchesa et al[29] reviewed 13 patients (12 women) with severe perianal CD (11 with RVF, 1 rectourethral fistula, 1 anal canal ulceration) who underwent sleeve advancement as an alternative to proctectomy. All patients had been previously treated with a rectal advancement flap without success. Eight patients had proximal fecal diversion, with six having concomitant bowel resection with a protective stoma at the same time of sleeve advancement. A 60% success rate was achieved by using the sleeve advancement flap in this carefully selected population of patients. Additionally, Simmang et al[30] reported successful healing in two patients with RVF secondary to CD using the sleeve advancement flap.

Patient selection and preparation are keys to achieve a satisfactory outcome with the sleeve advancement flap, therefore careful patient selection is crucial[29]. Fecal diversion is a controversial option with this technique and the majority of patients in Marchesa’s study appeared to have improved success rates for RVF closure when they were proximally diverted[29]. It is our practice currently to strongly consider diversion what performing a sleeve. This is typically an ileostomy. Meticulous surgical technique and adherence to principles such as hemostasis, gentle handling of tissues, and debridement of all diseased tissue is of paramount importance in this potentially technically demanding procedure. This repair is typically considered in a patient where the only other alternatives may be total proctocolectomy or permanent fecal diversion[29].

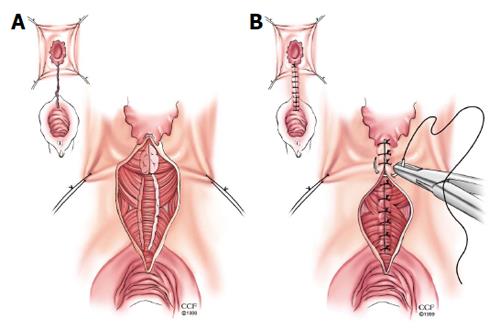

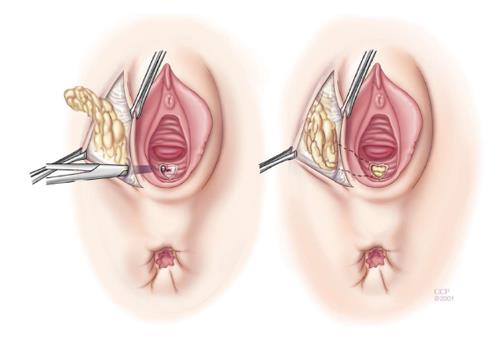

Episioproctotomy: When an anterior sphincter defect coexists in women with an RVF, the surgeon should strongly consider repairing the sphincter defect with the RVF repair[3]. This can be accomplished with either a rectal advancement flap performed in concurrence with an anterior sphincteroplasty[31] or as the case at our institution, an episioproctotomy is performed[32]. An episioproctotomy entails performing a fistulotomy and creating of a defect similar to a fourth degree perineal laceration during vaginal childbirth[32]. A compete debridement of the granulation tissue of the fistula tract is carried out along with lateral identification and mobilization of the sphincter muscles (Figure 3A). The rectal mucosa is repaired initially. Then an overlap of the sphincter muscles is accomplished. Finally the vaginal mucosa is approximated which completes the repair (Figure 3B). El-Gazzaz et al[6] from our institution reported their results of various methods of Crohn’s related RVF repair. There were 8 women who had an episioproctotomy with a healing rate of 71.4%.

Transverse transperineal repair: Particularly in the gynecological literature, an incision transversely through the perineal body is advocated to repair RVF. Dissection is carried out cephalad to the fistula tract and then the tract is transected with sharp dissection. The posterior vaginal and anterior rectal walls are mobilized and the cicatrix is excised. The vaginal and rectal walls are closed in 2 layers along with a levatoroplasty. Athanasiadis et al[33] reviewed various surgical techniques for CD RVF in 37 women undergoing 57 procedures with a mean follow-up of 7.1 years. Twenty women underwent transverse transperineal repair with a 70% overall success rate.

Vaginal advancement flap: The technique of repairing a RVF via the vaginal approach is considered by some surgeons a superior method due to the fact that the operation occurs not in the confines of the anal canal but in the vagina where the tissue is non-diseased, soft and pliable[27]. By avoiding the rectum, there is minimal to no manipulation or instrumentation in the potentially diseased and inflamed bowel. The vaginal advancement flap (VAF) consists of raising a posterior flap of vaginal tissue around the fistula. The rectal and vaginal orifices of the fistula are identified and repaired with absorbable sutures and the levator ani muscle is approximated in the midline. The vaginal flap is then advanced over the repair and sutured to the perineal skin.

Sher et al[34] reviewed their experience with 14 VAF for RVF in the setting of CD. They reported 13/14 patients achieved fistula closure. The authors attribute their success with using healthy tissue and also using the levator ani interposition to lend added support and further separation of suture lines. Of note, all 14 patients either had proximal diversion before or at the time of VAF with a loop ileostomy, which the authors felt to be an essential part of their success[34]. Furthermore, in a systematic review of eleven observational studies by Ruffolo et al[27], VAF was compared to RAF, with the primary end point of successful RVF closure rate. A total of 219 flap procedures (175 RAF vs 49 VAF) were reviewed and the authors noted a 54.2% closure rate after RAF and a 69.4% closure rate for VAF. This review suggests no significant differences in terms of outcome between VAF and RAF in CD. The VAF may be a good surgical option when there is anorectal stenosis or after a failed RVF repair.

Inversion of fistula: If the fistula is low and small, inversion may be an option. A circular incision is made around the vaginal os, and the surrounding flap of vaginal mucosa is mobilized. Several concentric purse-string sutures are placed to invert the fistula into the rectum. The vaginal mucosa is then reapproximated. All surrounding tissue must be soft and pliable for this approach to be considered. It should be noted that there is no reported data on this technique in Crohn’s related RVF.

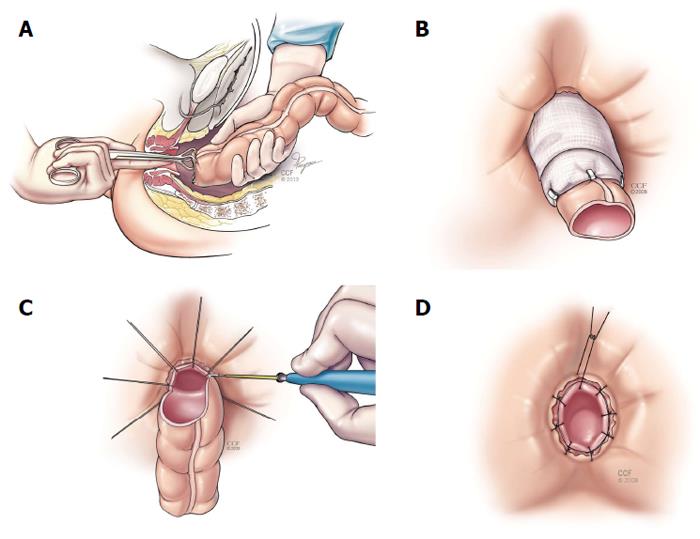

Coloanal anastomosis and turbull-cutait procedure: As mentioned previously, when performing the rectal sleeve advancement, a tension-free anastomosis may not be possible. In this scenario, a transabdominal approach is then used to complete the repair. This can be done with two main techniques: an immediate hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis or a delayed coloanal anastomosis (Turnbull-Cutait). After complete rectal (and if needed) descending and splenic flexure mobilization, the colon is passed transanally. If the local conditions in the anus are satisfactory, a standard hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis is performed immediately. When there are other fistulous tracts close to the neodentate line or the internal opening of the fistula is close to the suture line, a delayed coloanal anastomosis as described by Cutait and Turnbull[35-37] should be considered. The highlight of this procedure relies on placing 8 sutures around the anus through the neodentate line. Then the proximal bowel is extruded out the anus and (along with the sutures with needles) wrapped in gauze and stabilized. Then after 5-7 d the extruded bowel is amputated and using the already placed sutures, the coloanal anastomosis is completed (Figure 4). This delayed maturation allows the portion of the bowel in the anal canal to adhere to the denuded surface and seal prior to amputation. El-Gazzaz et al[6] reported on this technique in 7 patients with CD associated RVF, with a 57.1% healing rate.

Tissue interposition: Tissue interposition achieves bringing healthy, well vascularized tissue between the rectal and vaginal walls and acts as a buttress to suture lines as was mentioned in the transverse perineal approach above. Successful use of the gracilis muscle interposition has been reported for Crohn’s RVF repairs, especially after other failed repairs. Zmora et al[38] reported on their use of the gracilis flap in nine patients for various causes of fistula, including 3 rectourethral fistulae, 1 pouch-vaginal fistula, and 5 RVF (2 CD associated RVF). All patients underwent fecal diversion. Seven patients achieved successful closure with this technique, with 1 CD associated fistulae achieving closure. The authors emphasized the importance of fecal diversion, performing a tension-free rectal repair, and the use of a well-vascularized muscle pedicle. They recommend the gracilis interposition in failed RVF repairs and noted that even though the rate of success in CD is not as high as a surgeon would prefer, a gracilis transposition can be attempted and should be considered. Similarly, in a study by Lefèvre et al[39], 4/5 women with Crohn’s RVF were successfully closed at a 28 month follow-up, with the use of a gracilis muscle interposition.

The Martius (bulbocavernosus) flap may be used as an adjunct to transperineal repairs with anal sphincter reconstruction (Figure 5). The Martius flap has been reported to improve closure rates and possibly lead to better functional outcomes as well[40]. McNevin et al[40] reported on 16 patients with complex anovaginal fistulae, including 2 with CD. They reported success in 15 women and concluded that the Martius flap can be combined with an anterior sphincter repair for complex RVF with minimal morbidity.

Overall there are few studies utilizing the gracilis or Martius flaps in CD RVF. These studies have limited numbers of patients. Therefore it is not clear if the use of gracilis or Martius flaps improves outcomes after RVF repair.

Bioprosthetics: A bioprosthetic fistula plug made from lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa is a technically feasible option in closing RVF, but the data on its use in Crohn’s-related RVF is limited. Schwandner et al[41] reported using Surgisis™ mesh in 21 patients with RVF, 9 with Crohn’s RVF. After a mean follow up of 12 mo, they achieved a 78% closure rate in the Crohn’s group and an 83% closure rate in the non-Crohn’s RVF. The authors concluded that the mesh plug could be used as an adjunct to traditional advancement flap repair or muscle interposition, or possibly it could be used as an initial operation[41]. In a study by O’Connor et al[42], the use of the fistula plug was studied in patients with Crohn’s fistulae (2 with RVF) with an 80% success rate. The success of the two RVF was not specifically addressed. Alternatively, in a report from our institution, a retrospective review of 49 plug insertions in thirty-three patients was conducted (13 CD with 2 RVF; 19 cryptogenic origin). The authors reported an 84.6% failure rate for CD associated fistulae (including both RVF) and a 68.4% failure rate for fistulae from cryptogenic origin. These results were much lower than previous reports and the authors concluded that septic complications were the most common cause of failure[43].

Currently, there is little data to support the routine use of bioprosthetics in Crohn’s RVF, but the procedure carries a low morbidity and does not preclude further treatments. Further studies are required to determine the role of bioprosthetics in repair of CD associated RVF.

Stem cell transplantation: Adult stem cells extracted from certain tissues can differentiate into different tissue lines, including muscle. In a recent study by García-Olmo et al[44] from Spain, a female with Crohn’s associated RVF received autologous adipose stem cells that were injected into her RVF. At three month follow up, the patient achieved successful closure of the fistula[44]. This is an exciting potential therapy where further research is needed.

As previously mentioned, the use of fecal diversion in repair of Crohn’s associated RVF remains controversial. Proximal diversion does control symptomatology and likely improves the condition of the anorectum before subsequent repairs are undertaken. However, equivocal results are obtained whether or not proximal diversion is used in conjunction with RVF repair, regardless of the technique utilized[3]. There are no set criteria regarding when and in whom proximal diversion should be performed. Furthermore, a stoma does not ensure a successful repair. The literature is mixed with recommendations as some authors recommend all patients receive a loop ileostomy before or during repair and others recommend fecal diversion only in select situations. Without any randomized, prospective data, the creation of a stoma remains controversial and surgeons must use their best judgment in making the decision regarding diversion. Our institution recommends the construction of a proximal stoma in the following circumstances: re-do repairs, technically difficult repairs, and suboptimal tissue conditions[3].

Traditionally, proctectomy has been the definitive treatment of Crohn’s related RVF. In an early paper by Tuxen and Castro, total proctocolectomy (TPC) with an end ileostomy was the procedure of choice, due to shortcomings in medical treatment and proximal diversion to heal Crohn’s RVF[11]. Over the last several decades, successful repairs with sphincter and rectum sparing techniques have been widely published. Despite published studies of successful repairs for Crohn’s RVF, there are still subsets of patients who will require TPC. Patients with extensive colonic involvement or extensive anorectal involvement may not be candidates for definitive repair and proctectomy would be recommended as their initial step in treatment. It should be noted that proctectomy is not without its own complications, as delayed perineal wound healing and the potential for chronic perineal sinuses can be seen in up to 50% of patients in some series[5,22].

Long-term success after repair is not guaranteed regardless of the method used. Crohn’s related RVF have a high propensity to recur with a published range between 25%-50%[3,6,45-47]. Most studies have only reported short-term outcomes. Makowiec et al[25] evaluated perianal Crohn’s fistulae in 32 patients who underwent RAF (12 patients had a RVF). Mean follow-up was 19.5 mo. A recurrence rate in the women with RVF was 58%. The authors analyzed their results which showed a cumulative risk of recurrence at one year of 46% and 72% at 2 years.

Ruffolo et al[48] evaluated surgical outcomes in women with Crohn’s associated RVF over a 14 year period as well as assessing the effect of anti-TNF-α treatment on healing rates. With various techniques utilized, the authors found a fistula closure rate of 81% in 52 women. The cumulative closure rates after the first, second, third, and fourth attempt at repair was 56%, 75%, 78%, and 81%, respectively[48,49]. Furthermore, primary healing rates were found to be similar in patients receiving ant-TNF-alpha treatment vs those who did not.

In a long-term follow-up study from our institution, El-Gazzaz et al[6], studied potential variables that may influence success or failure of fistula closure in Crohn’s RVF. We also reported on quality of life and sexual function. With a median follow up of 44.6 mo, 30/65 (46.2%) had successful closure. Repair techniques were as follows: advancement flap (n = 47), episioproctotomy (n = 8), coloanal/Turnbull-Cutait (n = 7), and fibrin glue/plug (n = 3). The authors found that sexual function and quality of life were similar in healed vs unhealed women. Predictors of failure included smoking and steroids. The use of immunomodulator medications within 3 mo of repair showed a higher rate of fistula closure[6].

A retrospective study by Athanasiadis et al[33] reviewed rates of closure and functional outcomes in Crohn’s RVF repair techniques over a 7 year period. Thirty-seven women with RVF underwent 57 operations with various repair techniques. The authors found that techniques with a low degree of tissue mobilization had higher success rates and less postoperative functional problems.

Repair of recurrent fistulae or re-repair of a failed repair is plausible. A review of all methods of repair over nine years for recurrent RVF secondary to all etiologies was undertaken at our institution. An overall success rate of 79% was accomplished after a median of 2 operations. When looking specifically at Crohn’s associated recurrent RVF, 6/12 healed after a combined total of 21 operations. The authors noted that the most significant factor to influence outcome of repeat repairs was the duration of time between repairs. Patients re-operated within 3 mo of the original repair had lower healing rate compared to those treated after 3 mo. The authors highlighted that proper patient selection and optimization of clinical conditions is paramount in order to achieve the best possible outcome[46].

Rectovaginal fistulae are the most difficult manifestation of perianal CD to treat. They are a source of frustration for the patient and for the treating clinician. A thorough investigational work-up of the entire gastrointestinal tract, the anal sphincters, and the anorectum must be performed before any treatment attempt can be undertaken. Only after failed medical management and when local conditions are suitable, can surgical intervention be contemplated. Initial control of perianal sepsis with drainage and possible seton placement is paramount and may be the only treatment required. Medical treatments are indicated to control both local and distant active CD. Immunomodulators and anti-TNF-α therapy may play a role in primary correction of fistulae or may be used as an adjunct to surgical repairs. The surgical management of RVF can be complex and the treatment plan must be individualized. The chosen technique is based on the anatomy of the fistula, patient symptoms, and quality of life. The experience of the surgeon also influences the choice of repair and multiple options must be in one’s armamentarium. Often, repairs fail and reoperative intervention is necessary, with acceptable results. Maintaining realistic treatment goals and expectations is essential.

| 1. | Gabriel WB. Results of an Experimental and Histological Investigation into Seventy-five Cases of Rectal Fistulae. Proc R Soc Med. 1921;14:156-161. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 15, 1932. Regional ileitis. A pathological and clinical entity. By Burril B. Crohn, Leon Ginzburg, and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hannaway CD, Hull TL. Current considerations in the management of rectovaginal fistula from Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:747-755; discussion 755-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Radcliffe AG, Ritchie JK, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE, Northover JM. Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:94-99. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Heyen F, Winslet MC, Andrews H, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR. Vaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:379-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Analysis of function and predictors of failure in women undergoing repair of Crohn’s related rectovaginal fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Andreani SM, Dang HH, Grondona P, Khan AZ, Edwards DP. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2215-2222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maconi G, Parente F, Bianchi Porro G. Hydrogen peroxide enhanced ultrasound- fistulography in the assessment of enterocutaneous fistulas complicating Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1999;45:874-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Eijsbouts QA, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Hydrogen peroxide-enhanced transanal ultrasound in the assessment of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1147-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sloots CE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Poen AC, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Assessment and classification of fistula-in-ano in patients with Crohn’s disease by hydrogen peroxide enhanced transanal ultrasound. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tuxen PA, Castro AF. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morrison JG, Gathright JB, Ray JE, Ferrari BT, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE. Results of operation for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:497-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bernstein LH, Frank MS, Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Healing of perineal Crohn‘s disease with metronidazole. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:357-365. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, Glass JL, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 802] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1868] [Article Influence: 69.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Present DH, Lichtiger S. Efficacy of cyclosporine in treatment of fistula of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sands BE, Blank MA, Patel K, van Deventer SJ. Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:912-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Faucheron JL, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, Parc R. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease--a sphincter-saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:208-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thornton M, Solomon MJ. Long-term indwelling seton for complex anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:459-463. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hesterberg R, Schmidt WU, Müller F, Röher HD. Treatment of anovaginal fistulas with an anocutaneous flap in patients with Crohn‘s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8:51-54. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Greenwald JC, Hoexter B. Repair of rectovaginal fistulas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:443-445. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Cohen JL, Stricker JW, Schoetz DJ, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn‘s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:825-828. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Hull TL, Fazio VW. Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173:95-98. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kodner IJ, Mazor A, Shemesh EI, Fry RD, Fleshman JW, Birnbaum EH. Endorectal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas. Surgery. 1993;114:682-689; discussion 689-690. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Clinical course after transanal advancement flap repair of perianal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1995;82:603-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Crim RW, Fazio VW, Lavery IC. Rectal advancement flap repair in Crohn’s disease. Factors predictive of failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:3. |

| 27. | Ruffolo C, Scarpa M, Bassi N, Angriman I. A systematic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: transrectal vs transvaginal approach. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Berman IR. Sleeve advancement anorectoplasty for complicated anorectal/vaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:1032-1037. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Marchesa P, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Advancement sleeve flaps for treatment of severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1695-1698. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Simmang CL, Lacey SW, Huber PJ. Rectal sleeve advancement: repair of rectovaginal fistula associated with anorectal stricture in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:787-789. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Khanduja KS, Padmanabhan A, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Aguilar PS. Reconstruction of rectovaginal fistula with sphincter disruption by combining rectal mucosal advancement flap and anal sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1432-1437. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Hull TL, El-Gazzaz G, Gurland B, Church J, Zutshi M. Surgeons should not hesitate to perform episioproctotomy for rectovaginal fistula secondary to cryptoglandular or obstetrical origin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Athanasiadis S, Yazigi R, Köhler A, Helmes C. Recovery rates and functional results after repair for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: a comparison of different techniques. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1051-1060. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Sher ME, Bauer JJ, Gelernt I. Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: transvaginal approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:641-648. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Kirwan WO, Turnbull RB, Fazio VW, Weakley FL. Pullthrough operation with delayed anastomosis for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1978;65:695-698. [PubMed] |

| 36. | CUTAIT DE, FIGLIOLINI FJ. A new method of colorectal anastomosis in abdominoperineal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1961;4:335-342. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Cutait DE, Cutait R, Ioshimoto M, Hyppólito da Silva J, Manzione A. Abdominoperineal endoanal pull-through resection. A comparative study between immediate and delayed colorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:294-299. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Zmora O, Tulchinsky H, Gur E, Goldman G, Klausner JM, Rabau M. Gracilis muscle transposition for fistulas between the rectum and urethra or vagina. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1316-1321. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Lefèvre JH, Bretagnol F, Maggiori L, Alves A, Ferron M, Panis Y. Operative results and quality of life after gracilis muscle transposition for recurrent rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1290-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | McNevin MS, Lee PY, Bax TW. Martius flap: an adjunct for repair of complex, low rectovaginal fistula. Am J Surg. 2007;193:597-599; discussion 599. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Schwandner O, Fuerst A, Kunstreich K, Scherer R. Innovative technique for the closure of rectovaginal fistula using Surgisis mesh. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:135-140. [PubMed] |

| 42. | O’Connor L, Champagne BJ, Ferguson MA, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of Crohn’s anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1569-1573. [PubMed] |

| 43. | El-Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Hull T. A retrospective review of chronic anal fistulae treated by anal fistulae plug. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | García-Olmo D, García-Arranz M, García LG, Cuellar ES, Blanco IF, Prianes LA, Montes JA, Pinto FL, Marcos DH, García-Sancho L. Autologous stem cell transplantation for treatment of rectovaginal fistula in perianal Crohn’s disease: a new cell-based therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:451-454. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Joo JS, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Endorectal advancement flap in perianal Crohn’s disease. Am Surg. 1998;64:147-150. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Halverson AL, Hull TL, Fazio VW, Church J, Hammel J, Floruta C. Repair of recurrent rectovaginal fistulas. Surgery. 2001;130:753-757; discussion 757-758. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ozuner G, Hull TL, Cartmill J, Fazio VW. Long-term analysis of the use of transanal rectal advancement flaps for complicated anorectal/vaginal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:10-14. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Ruffolo C, Penninckx F, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Coremans G, D’Hoore A. Outcome of surgery for rectovaginal fistula due to Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1190-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zhu YF, Tao GQ, Zhou N, Xiang C. Current treatment of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:963-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: O'Riordan JM S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH