INTRODUCTION

Diverticular disease (DD) is a very common entity in the general population. Although this condition may develop anywhere along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, current evidence demonstrates that the sigmoid colon is the most frequently affected area. The prevalence has been reported in up to 50% of people 60 years and older[1,2]. However, the incidence increases as the population becomes older. Therefore, current knowledge states that rates can be as high as 70% in patients over 80 years old. Nonetheless, this proportion can go down to 10% in patients under 40 years old. Clinical presentation is proportional for both genders[1,2]. Although intraluminal pressure has been reported as the basic mechanism for diverticula development, the etiopathology remains incompletely understood[1]. DD is often described as asymptomatic. However, nonspecific abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and malabsorption are chronic clinical presentations in one-quarter of the patients[3], and 12% of patients experience complications such as perforation, bleeding, and obstruction. Intestinal diverticula is the leading cause of lower GI bleeding with a prevalence that exceeds 20% of hospitalized patients[4,5].

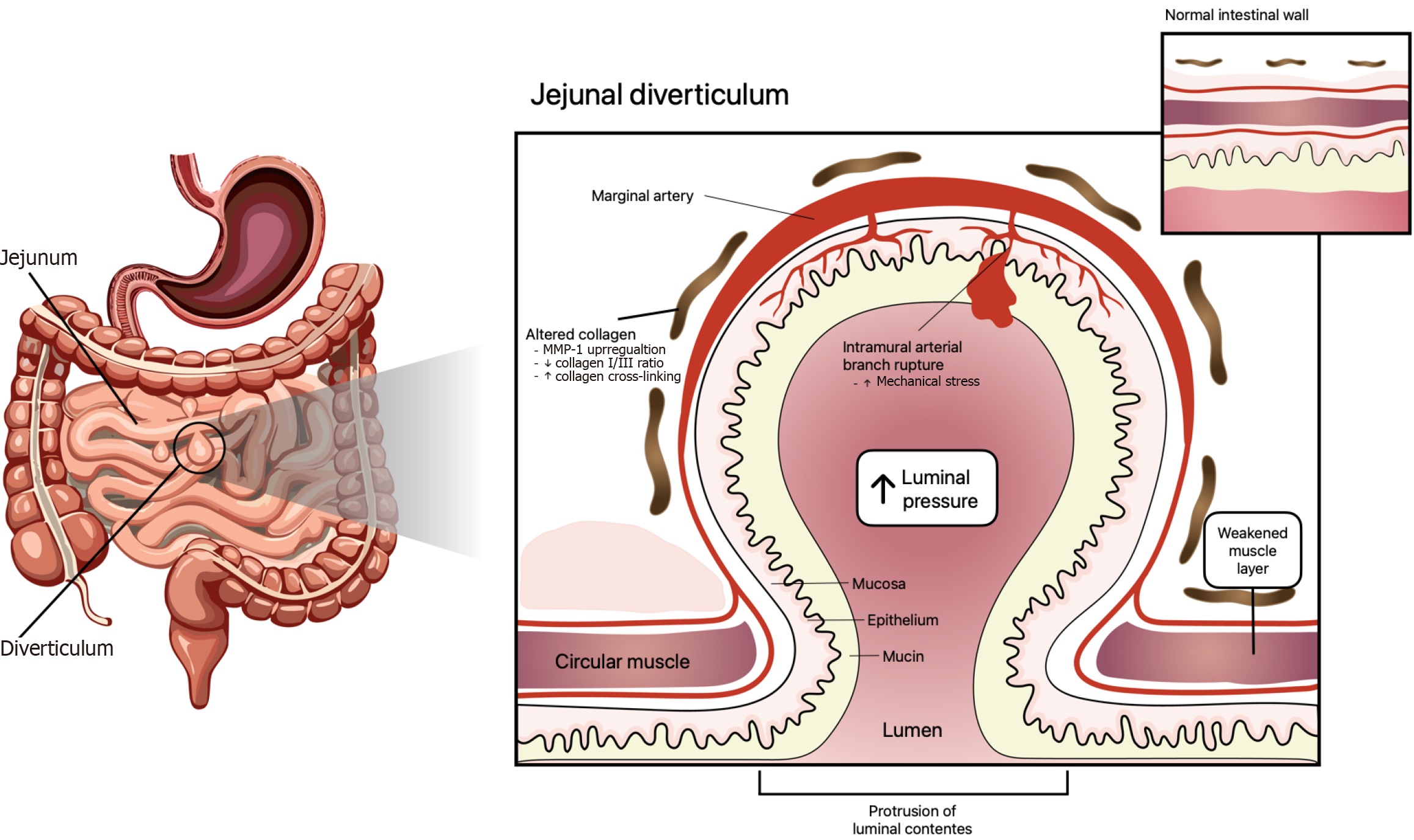

Ileojejunal diverticulosis is a less common presentation with a prevalence that has been reported between 0.3% and 2.3% of the cases. Paradoxically, this area of the GI tract bears the highest rate of diverticula diagnosis. The presence of more evident symptoms, such as bleeding, explains this tendency. However, 80%-85% of the lower GI bleeding arises distal to the ileocecal valve[5-9], whereas the small bowel is the source of GI hemorrhage in only 0.7%-9.0% of the cases. In summary jejunal diverticula are less common but show a higher tendency to bleed than diverticula in the colon[9-12]. Jejunum diverticula share the same basic development mechanism as any other diverticula along the GI tract. The triggering phenomenon is increased intraluminal pressure. Nevertheless, small differences have been reported in the literature. Hemorrhage is caused by the rupture of intramural branches coming out from marginal arteries. This can take place at the top or base of the diverticulum. Either mechanical or chemical trauma can cause the arterial bleeding. This sequence of events leads to damage to the penetrating vessels with subsequent hemorrhage (Figure 1)[6].

Figure 1 Complex interaction of different elements in the development and progression of diverticular disease.

The triggering element is chronic increased intraluminal pressure. Sustained mechanical stress leads to structural alterations in the intestinal wall, including decreased collagen I/III ratio and excessive collagen fiber cross-linking. Concurrently, upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 1 promotes degradation of fibrillar collagens, further weakening the submucosa and muscularis layers. These changes weaken wall compliance and favor mucosa and submucosa herniation through the muscularis propria, especially where marginal arteries penetrate the intestinal wall. MMP-1: Matrix metalloproteinase-1.

Multiple diverticula are most commonly found near the Treitz ligament. A common occurrence that has been reported in the literature is jejunal diverticula associated with colon and duodenum diverticulosis. This presentation has been considered by some authors as a silent entity. However, non-complicated chronic symptoms that have been reported include: Nausea; vomiting; diarrhea; vague abdominal pain; and bleeding. Current evidence reveals that GI diverticulosis may become complicated in 10% of the cases[13]. These complications involve but are not limited to: Bowel obstruction; severe hemorrhage; diverticulitis; perforation; and resulting peritonitis. These complications can ultimately lead to a fatal outcome[14]. Accordingly, diverticulosis is rather a challenging diagnosis owing to an asymptomatic behavior. Therefore, reaching a diagnosis either by accident or after a complication occurs frequently. The most commonly used diagnostic tool is CT of the abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast, followed by endoscopy. These two studies help to identify complicated cases and to plan the surgical approach. Other alternatives involve angiography, swallowed barium, and finally exploratory laparotomy[15]. In patients with non-complicated symptoms, such as anemia and diarrhea, a conservative management is indicated. This approach is also justified for most GI bleeding episodes. However persistent (active) hemorrhage after conservative medical support justifies a surgical approach to find and treat the bleeding source[16].

METHODOLOGY

We performed a systematic review of PubMed and Scopus for potentially relevant articles. Databases were searched from inception to May 2025. Key search terms employed were “jejunal diverticular diseases, GI diverticular disease, and diverticulitis”. Main outcomes were diverticular bleeding, complications, epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical presentation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of GI DD is remarkable. This prevalence has increased in developed countries while it is considered a rare entity in Eastern countries. Current studies report a 50% occurrence in patients 60 years and older. This incidence increases as the population gets older. This tendency grows to 70% in patients over 80 years old. Conversely, the occurrence of DD declines significantly in younger individuals. Accordingly, only 10% of patients under 40 years old are affected by diverticulosis. In general DD prevalence is the same for both genders. These findings highlight the importance of age as a significant risk factor for DD and the need for targeted screening and management strategies, especially in elderly populations[2-4,17-19].

It is important to highlight that diverticula may develop anywhere along the GI tract. Although occurrence is different in the colon (30%-75%), duodenum (15%-42%), stomach (2%), and esophagus (2%). Therefore, diverticulosis is more prevalent in the colon. Ileojejunal diverticulosis, though less common than colon diverticula, carries a significant risk of complications. Approximately, 75% of cases involve diverticula in the proximal jejunum, 20% in the distal jejunum, 15% in the distal ileum and 5% appear in both[15,20-22]. Additionally, studies have revealed an association between the presence of diverticula in the colon and the duodenum. As many as 60% of patients with jejunal diverticula may also suffer simultaneous colonic diverticula. Recent reports describe that jejunal diverticulosis is associated with colon, duodenum, and esophageal diverticula in 35%, 26%, and 2% of cases, respectively. The simultaneous association of jejunal diverticula with either colon, duodenum, or esophageal diverticula predominantly occurs in elderly patients with a 2:1 male to female ratio[13,16].

PATHOGENESIS

GI DD is a clinical condition characterized by sac protrusions in the intestinal wall. The accurate etiology of this condition remains incompletely understood. Nonetheless, the cumulative impact of increased intraluminal pressure is the most accepted hypothesis. This phenomenon leads to structural changes in the intestinal wall, characterized by increased collagen cross-linking and reduced elasticity[23]. Recent evidence states that the multifactorial nature of this condition involves different elements, such as low-fiber diet, neuroimmune and enteric systems disruptions, dysbiosis in the gut microbiota, mucosal injury, and inflammation resulting from fecal matter (Figure 1)[23-25].

Small intestinal bacterial and fungal overgrowth have recently been reported as conditions leading to an abnormal increase in microbial populations. The hypothesis is that bacterial overgrowth is associated with impaired GI motility and structural abnormalities, finally leading to increased bowel pressure and diverticula development[26]. DD has been reported because of mesenchymal tumors that appear in the small intestine. These tumors include GI stromal tumor and malignant gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors[22]. As a result there is a complex interaction of many factors in the development and progression of DD. Therefore, therapeutic strategies should consider all contributing elements to improve outcomes.

Although the exact origin of jejunal diverticulum is not fully understood, current knowledge points towards a combination of factors (Figure 1). Abnormal intestinal motility is thought to be one of the main contributing elements. Accordingly, altered bowel motility leads to increased intraluminal pressure. This may be the result of high collagen production, which leads to a loss of elasticity in the intestinal wall. In addition structural weaknesses in areas where blood vessels and nerves penetrate the intestinal wall play a key role in diverticula development[27,28]. Therefore, there is a complex interaction between functional and structural components of the intestinal wall[17,28]. While this etiopathological hypothesis provides valuable insight, further research is necessary to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Understanding the etiology of jejunal diverticulum is crucial to reach a diagnosis, ultimately improving treatment strategies and patients’ outcomes.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

DD is frequently described as an asymptomatic GI disorder. That is, medical history and physical examination can be unreliable in many cases. Nevertheless, around 25% of individuals will experience persistent clinical manifestations such as vague abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, malabsorption issues, flatulence, and diarrhea[23,29,30]. Furthermore, clinical complications occur in approximately 12% of the cases. Some of the complications that have been reported include perforation, hemorrhage, obstruction, and abscess or fistula development[23]. As indicated earlier DD is more prevalent in the colon and is frequently associated with symptomatic presentations such as diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding[31]. Current evidence demonstrates that the use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants in the elderly population has increased the incidence of acute diverticular bleeding, and about 50% of these patients will require blood transfusion. It is estimated that up to 53% of the patients with diverticular bleeding need emergency surgery to control the bleeder[19]. Diverticula in other areas of the GI tract may represent a clinical challenge that requires a more tailored approach for an adequate treatment[6,9,10,32]. For that reason a thorough understanding of diverse clinical presentations is mandatory to optimize patient care and outcomes.

Jejunal diverticula are frequently considered a silent condition. This implies that they may not exhibit perceivable symptoms in many cases. However, it is very important to know that individuals with jejunal diverticula can experience non-complicated chronic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, vague abdominal pain, occasional bleeding, and altered bowel habits[32,33]. Moreover, these seemingly benign symptoms can escalate into more serious complications, including bowel obstruction, severe hemorrhage, diverticulitis, perforation, and subsequent peritonitis. Risk factors for acute diverticulitis include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, increased body mass index, a low-fiber diet, and the use of steroids, opioids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[22]. Any of these complications can ultimately lead to fatal outcomes if left untreated. Perforation has been associated with a 40% mortality rate[6-10,13,20,33]. Jejunal diverticula are frequently diagnosed when complications occur, and hemorrhage has been the most commonly reported complication[20,28]. This highlights the importance of recognizing and addressing potential complications early in the course as they can significantly impact patient prognosis. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of jejunal diverticula, particularly when the patient shows signs of either unexplained GI symptoms, acute abdomen, or both. Hence, early diagnosis and management are crucial to prevent adverse outcomes.

DIAGNOSIS

A common diagnostic imaging tool is CT of the abdomen with intravenous and oral contrast. It provides valuable information regarding the presence and extent of the condition (diverticula). However, cost and radiation exposure have been described as drawbacks in many cases. Ultrasound has been reported with greater sensitivity and specificity in cases of acute diverticulitis. Additionally, interventional procedures, such as enteroscopy and exploratory laparotomy, play key roles in identifying complications early in the course[31,33]. The current challenge when acute diverticulitis develops is to identify those patients who may require surgery, and anticipating the severity of the disease is a key element to indicate surgery in these cases. Hinchey classification provides guidance for surgical management. Recent studies have demonstrated that red cell distribution width is associated with disease activity in various GI conditions. This evidence suggests that red cell distribution width may serve as a biomarker to predict severity of diverticulitis[34].

The diagnosis of jejunal diverticular bleeding is a rather complex task. Conventional radiological procedures, such as enteroclysis and contrast-enhanced tomography, do not help in identifying the bleeding source. Accordingly, the study protocol for GI hemorrhage does not include these procedures. However, capsule endoscopy and double-balloon endoscopy have been described as excellent alternatives for the study of GI bleeding. But their usefulness is very limited in emergency situations[10,16,20,33,35,36]. Upper and lower endoscopy are part of the protocol when studying unidentified GI bleeding. When these two studies are negative, video capsule endoscopy is the next recommended test[37], especially when a small bowel source is suspected.

MANAGEMENT

It has been demonstrated that timely interventions improve outcomes in DD[7,10,35,38]. However, not all patients are suitable for surgical management. Consequently, medical treatment is a good alternative for patients whose main complaint is diarrhea and anemia without any complications[20,33]. This approach ensures that patients without complications receive appropriate care based on the severity and nature of their symptomatology, ultimately optimizing outcomes and quality of life.

In patients without complications the initial recommended therapeutic approach is medical support. However, recent evidence indicates that weeks later a significant number of patients will develop complications when non-invasive treatments are implemented. Anyhow, persistent hemorrhage demands patient stabilization while locating the bleeding source[20,33]. Angiography may help to find the bleeder and allow the use of other non-surgical alternatives. Specifically, transarterial embolization should be considered in high-risk selected patients[16,20,35,36,39]. Postoperative mortality has been reported in 43% of the patients when the bleeding source was not identified compared with a 7% postoperative mortality rate of those cases undergoing surgery in which a bleeding source was identified[6]. Though jejunal diverticulosis is infrequent, most cases have been identified because of complications like bleeding and perforation. Evidently, these clinical presentations represent significant risks for the patient. Evidence in the literature reports that 10%-15% of the cases will require surgical intervention due to complications such as perforation, obstruction, peritonitis, or GI bleeding[5,9,10,20,32,36]. Mortality rates have been reported in 40% of patients suffering from perforation because of jejunal diverticulitis[13].

CONCLUSION

Identifying the distribution of diverticula along the GI tract is essential for an accurate and timely diagnosis. Although uncommon jejunal diverticulosis represents a serious threat to the well-being of those patients suffering from this condition. Therefore, it is imperative to prioritize its recognition as a potential cause of GI bleeding. There is a strong association between colon and jejunal diverticula. Accordingly, differential diagnosis should include ileojejunal diverticulosis in cases of unidentified GI bleeding and associated colon diverticula. Early detection and timely treatment can significantly improve the patients’ prognosis, reducing morbidity and mortality. Future research should focus on the gut microbiome and dysbiosis to further understand impaired GI motility and structural abnormalities leading to increased bowel pressure.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade D

Novelty: Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade D

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade D

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Joseph BC, PhD, Senior Scientist, United States; Lopes SR, MD, Portugal S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang WB