Published online Sep 22, 2025. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v16.i3.108900

Revised: May 12, 2025

Accepted: June 13, 2025

Published online: September 22, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 15.4 Hours

Dysphagia is a prevalent condition affecting over 15 million adults in the United States, posing serious health risks and contributing to rising healthcare costs. Early evaluation, often initiated by speech-language pathologists (SLPs) using the modified barium swallow study (MBSS), is essential to identify underlying causes. Although SLPs have traditionally focused on oropharyngeal swallowing, emerging guidelines now support esophageal visualization during MBSS. However, standardized practices and consensus remain limited. This study hypothesizes that incidental esophageal retention observed on MBSS do not correlate with clinically relevant esophageal dysphagia.

To assess whether abnormal esophageal retention on MBSS predicts clinically relevant esophageal disease based on subsequent diagnostic studies.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with abnormal MBSS findings who were referred to gastroenterology (GI) for dysphagia between September 2017 and August 2023. Patients with prior foregut/head/neck surgery or without esophageal phase evaluation on MBSS were excluded. Baseline characteristics, MBSS findings and results from subsequent esophageal studies within one year of MBSS were analyzed. Patient profiles were evaluated by two raters to determine whether subjects had confirmed esophageal pathology. χ2 tests compared MBSS findings with esophageal study abnormalities.

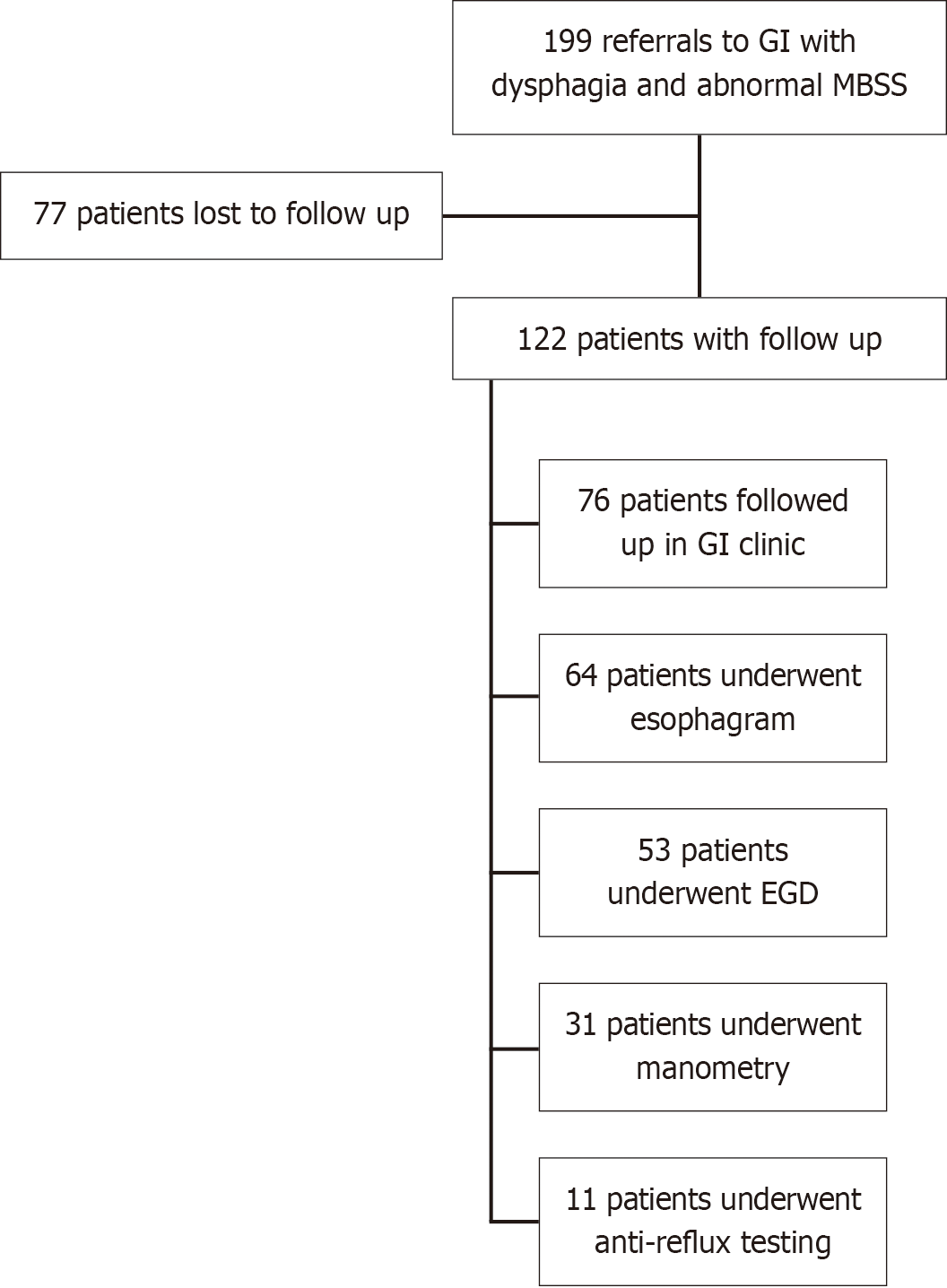

Of 199 referrals to GI with abnormal MBSS findings, 122 patients had subsequent esophageal studies or GI clinic follow-up. Esophagram was performed in 64 patients, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in 53 patients, manometry in 31 patients, and anti-reflux monitoring in 11 patients. Confirmed esophageal pathology was identified in 27 patients. No significant association was observed between esophageal retention on MBSS and confirmed esophageal pathology (χ2 = 0.30, P value = 0.58) or with abnormal pathology on EGD, esophagram, manometry or anti-reflux testing in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Esophageal retention on MBSS does not reliably predict esophageal pathology and is not an effective standalone screening tool for esophageal dysphagia, though it may offer limited theoretical insights.

Core Tip: This retrospective cohort study evaluated whether esophageal retention observed during modified barium swallow studies (MBSS) predicts clinically relevant esophageal pathology. Among 122 patients with follow-up esophageal studies, no significant association was found between MBSS retention findings and confirmed esophageal disease. These results suggest that while MBSS esophageal visualization may offer theoretical insights, it is not a reliable standalone screening tool for esophageal dysphagia. This study underscores the need for standardized guidelines and multidisciplinary evaluation in dysphagia assessment.

- Citation: Chen SL, Partida D, Wang C, Kathpalia P. Esophageal retention on modified barium swallow study: Limited predictive value for true esophageal pathology. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025; 16(3): 108900

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v16/i3/108900.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v16.i3.108900

Dysphagia presents significant health risks and imposes considerable financial burdens, contributing to rising healthcare costs of an aging population[1-4]. Dysphagia is a symptom of underlying disease, with an estimated 15.10 million adults in the United States (over 1 in 20 individuals) experiencing swallowing difficulties during their lifetime[5]. Careful assess

Evaluation and management of dysphagia often begins with collaboration between speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and otolaryngologists as a first-line approach. SLPs typically begin evaluating swallowing disorders through the use of the modified barium swallow study (MBSS), which serves as a key diagnostic tool in early assessment, offering real-time visualization of both anatomy and motility[6]. The evaluation of swallowing is often divided into oropharyn

Despite its potential utility, there remains a lack of consensus among healthcare professionals and limited guidelines for performing and interpreting esophageal visualization during the MBSS. Patients with incidental findings of esopha

This retrospective cohort study included patients aged 18 years and older with abnormal findings on a MBSS (MBSS who were referred to the GI clinic for evaluation of dysphagia). These abnormalities included esophageal retention (with or without retrograde flow), penetration-aspiration (defined as a score greater than one on the Rosenbek Penetration-Aspiration Scale[18], indicating contrast entering the airway), or anatomical anomalies such as diverticula or strictures. Data were collected from a prospectively maintained electronic database at our institution for the period between September 2017 and August 2023. Patients were included if they had undergone subsequent esophageal diagnostic studies—esophagram, EGD, manometry or anti-reflux testing—or had a GI clinic visit within 1 year of the MBSS. Exclusion criteria included a history of foregut or head and neck surgery and the absence of esophageal phase evaluation during the MBSS. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco, United States.

An a priori power analysis was conducted. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, and based on findings of comparable studies[19-22]. An effect size of 0.36 was used with power set at 0.80 and alpha at 0.05 to determine that n = 23 in each group was required to conduct χ2 analyses comparing MBSS esophageal retention and confirmed esophageal pathology on more specific tests for esophageal function.

Board-certified, fellowship-trained speech and language pathologists performed all swallow and MBSS examinations and interpreted the results in conjunction with board certified radiologists. For each clinical swallow evaluation, a penny taped to the patient’s neck was used as a calibration measurement marker. Patients were presented with 1 cc and 20 cc nectar thick liquid single barium sips to objectively quantify swallowing kinematics, to compare to normative data, and to assess aspiration risk. MBSS examinations were performed with video fluoroscopic recording and screen captures to document esophageal anatomy, function and motility. Patients were presented with single and serial Varibar thin liquid sips, barium paste, gram cracker, and tablet and thin liquid. Examination interpretation consisted of the following criteria using real-time assessment and review of fluoroscopic/radiographic images: (1) Bolus penetration; (2) Bolus aspiration (rated on the Rosenbek Penetration-Aspiration Scale); (3) Esophageal narrowing; (4) Esophageal diverticula; and (5) Abnormal esophageal motility (which included esophageal dysmotility, reflux, presence of tertiary contractions, and delayed gastric emptying). Visualization was assessed in the lateral and a P planes.

All patients underwent some form of follow-up esophageal function testing: (1) EGD; (2) Esophagram; (3) Manometry; and (4) Anti-reflux potential of hydrogen (pH) testing.

EGD was performed as part of some patients’ evaluations to visualize the upper gastrointestinal tract and assess structural abnormalities. The procedure was completed by a board-certified gastroenterologist and involved inserting a flexible endoscope to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum under sedation. Findings, including the presence of esophagitis, strictures, or other anatomical and functional anomalies, were recorded and reviewed.

All esophagrams were performed by board certified radiologists using a standard barium swallow protocol. Patients ingested a contrast medium under fluoroscopic guidance to evaluate esophageal motility, structure, and transit. The studies were assessed for abnormalities such as strictures, dysmotility, or evidence of reflux. Additionally, findings suggestive of hiatal hernia or other anatomical variations were documented.

All manometry studies were performed in the supine position and interpreted by a single esophagologist. Motility diagnoses were reported based on the Chicago Classification (CC) v 3.0; hypercontractility motility disorders included jackhammer esophagus and distal esophageal spasm; disorders of hypocontractility included absent peristalsis, ineffective esophageal motility and fragmented peristalsis. Additional data including lower esophageal sphincter integrated relaxation pressures, and the presence of anatomical abnormalities such as hiatal hernia was also collected.

For anti-reflux pH monitoring, the procedure was completed by a single esophagologist and involved the placement of a pH sensor in the distal esophagus using a catheter. The pH monitor recorded the frequency and duration of acid reflux episodes over a 24-hour period, with data collected during both daytime and nighttime to assess the full range of reflux activity. All studies were performed after stopping proton-pump inhibitors at least 5 days and histamine-2 receptor antagonists at least 1 day prior to the test.

Baseline demographic information, MBSS findings, initial GI clinic notes, medication histories, and results of esophageal studies performed within 1 year of the MBSS were systematically extracted. Two independent reviewers manually analyzed GI clinic notes to identify symptoms of swallowing dysfunction, including dysphagia, reflux, heartburn, dyspepsia, cough, and globus sensation. MBSS reports were reviewed independently by the same 2 raters to classify cases as either normal or abnormal esophageal retention.

Additionally, findings from esophagram, EGD, manometry and anti-reflux testing were reviewed to code and document specific clinically significant abnormalities and diagnoses. For esophagram, any mention of major structural abnormalities or motility issues such as difficulty swallowing the barium tablet were coded as abnormal. Mild esophageal dysmotility, mild reflux and small structural abnormalities such as hiatal hernias < 4 cm were coded as clinically insignificant. For EGD, the focus was placed on identifying structural abnormalities such as hernias > 4 cm and esophageal strictures, though major functional abnormalities such as absent contractility were also noted. For patients who received manometry testing, abnormalities were coded based off CC, and for anti-reflux testing, patents were evaluated based on their total esophageal acid exposure time while also assessing DeMeester scores.

To evaluate the presence of esophageal pathology, comprehensive patient profiles, including all gastrointestinal clinic notes and subsequent esophageal studies, were reviewed by two board-certified gastroenterologists with specialized training in esophageal disorders. Any discrepancies in data coding or classification were resolved through collaborative consensus discussions between the 2 specialists.

χ2 tests compared MBSS findings with confirmed cases of esophageal dysphagia. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 29 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). All reported P values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Demographic data and breakdown of the study population are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. Of the 199 referrals to GI with abnormal MBSS findings, 122 patients had subsequent esophageal studies and/or GI follow-up, and the remaining 77 patients were referred to GI but lost to follow up. Demographic characteristics were comparable between patients who received follow-up and those who did not (Table 1).

| Variable | Patients with follow-up (n = 122) | Patients lost to follow-up (n = 77) |

| Birth sex: Male | 55 (45.1) | 37 (48.1) |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 64.02 (16.0) | 64.7 (16.4) |

| Body mass index [mean (SD)] | 26.1 (6.2) | 26.58 (7.7) |

| Modified barium swallow study: Esophageal retention present | 84 (68.9) | 57 (74.0) |

| Main presenting symptom in gastroenterology clinic (n = 76) | N/A | |

| Dysphagia | 63 (82.9) | |

| Reflux | 2 (2.63) | |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (6.58) | |

| Other (cough, belching, diarrhea, etc.) | 6 (7.89) | |

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (n = 53, some patients with > 1 abnormality) | N/A | |

| Any abnormality | 27 (50.9) | |

| Achalasia | 6 (11.3) | |

| Diverticulum | 5 (9.4) | |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 5 (9.4) | |

| Esophagitis (non-eosinophilic) | 7 (13.2) | |

| Hiatal hernia > 4 cm | 4 (7.5) | |

| Stricture | 5 (9.4) | |

| Esophagram: Abnormality present (n = 64) | 39 (60.9) | N/A |

| Manometry: Chicago classification (n = 31) | N/A | |

| Normal | 17 (54.8) | |

| Achalasia | 4 (12.9) | |

| Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction | 6 (19.4) | |

| Hypercontractile | 1 (3.2) | |

| Ineffective esophageal motility | 3 (9.9) | |

| Anti-reflux testing: DeMeester (n = 11) | N/A | |

| < 14.7 | 7 (63.6) | |

| > 14.7 | 4 (36.4) | |

| Anti-reflux testing: Potential of hydrogen total acid exposure (n = 11) | N/A | |

| < 4% | 8 (72.7) | |

| 4%-6% | 0 (0) | |

| > 6% | 3 (27.3) | |

| Confirmed esophageal pathology1 | N/A | |

| No | 56 (45.9) | |

| Yes | 27 (22.1) | |

| Equivocal/Incomplete testing | 39 (32.0) |

The majority of 122 patients with follow-up had evidence of esophageal retention on MBSS (n = 84, 68.9%). This included patients with retrograde flow, esophageal diverticulum, esophageal stricture, among other abnormalities. A total of 76 patients followed up in GI clinic, with dysphagia (n = 63, 82.9%) being the most common presenting symptom.

Esophagram was performed in 64 patients, with 39 (60.9%) patients having a major structural or functional abnorma

No significant association was found between esophageal retention on MBSS and confirmed esophageal pathology (χ2 = 0.30, P value = 0.58) or with abnormal pathology on EGD, esophagram, manometry or anti-reflux testing (Table 2). These findings remained non-significant after adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index (Table 3).

| Confirmed esophageal pathology1 | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy abnormality | Esophagram abnormality | Manometry abnormality2 | Anti-reflux abnormality3 | ||||||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||||

| Modified barium swallow study | No | 20 | 8 | χ2 = 0.30 | 7 | 8 | χ2 = 0.05 | 10 | 11 | χ2 = 0.96 | 8 | 5 | χ2 = 0.41 | 1 | 1 | χ2 = 0.20 |

| Yes | 36 | 19 | P = 0.58 | 19 | 19 | P = 0.83 | 15 | 28 | P = 0.33 | 9 | 9 | P = 0.52 | 6 | 3 | P = 0.66 | |

Swallowing impairments often span multiple phases, and accurately localizing the level of dysphagia based solely on history and physical examination remains challenging. Differentiating oropharyngeal from esophageal dysphagia can be particularly difficult due to overlapping or ambiguous symptom presentations. The MBSS is frequently employed as an initial diagnostic tool for dysphagia in otolaryngology offices due to its non-invasive nature and ability to assess oropharyngeal swallowing while providing the opportunity to visualize the esophageal phase of swallowing. Recent efforts to establish objective, standardized criteria for abnormal bolus flow on MBSS have improved inter-rater reliability among physicians and SLPs[20]; however, the utility of MBSS in diagnosing esophageal motility disorders remains controversial[7,11,12,17]. For example, the American College of Radiology Practice Parameter for the Performance of the MBSS published in 2023 indicates that esophageal phase may be viewed during testing; however, this is not to be used for diagnosis of esophageal disorders.

Our study aimed to assess the clinical utility of MBSS as a screening tool by examining its correlation with subsequent esophageal studies and its diagnostic yield in identifying clinically significant esophageal pathology. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare suspected esophageal retention observed on MBSS with a composite of subse

Our findings highlight the limited diagnostic accuracy of MBSS for esophageal dysphagia. We observed a 64.3% false-positive rate for esophageal retention and a 29.6% false-negative rate, highlighting the inadequacy of MBSS in reliably assessing esophageal retention and motility patterns. These results suggest that MBSS alone is insufficient as a standalone screening tool for esophageal dysphagia.

Indeed, there is notable variability in both performance and interpretation of the MBSS within the field of speech-language pathology practice[23]. Our findings are consistent with prior studies showing poor agreement between MBSS and confirmatory esophageal diagnostic tests. Prior literature has shown that esophageal visualization in MBSS often lacks the sensitivity required to detect functional disorders such as ineffective esophageal motility or transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation[24]. Physiological mechanisms underlying esophageal motility disorders involve complex interactions between the central and enteric nervous systems and the esophageal musculature, which includes both skeletal and smooth muscle components. Prior studies have shown that these interactions are best assessed through continuous pressure measurements rather than visual imaging[25-27]. Additionally, MBSS is typically performed over a short fluoroscopic window and does not offer the extended monitoring available in esophagrams or 24-hour pH testing, thereby reducing its diagnostic yield for episodic phenomena such as reflux or transient bolus stasis. Esophageal retention visualized during MBSS may also be due to benign or age-related phenomena rather than underlying pathology. Multiple studies have shown that aging is associated with decreased esophageal contractile amplitude, increased non-propulsive tertiary contractions, and delayed bolus clearance, even in asymptomatic individuals[28-30]. Our findings underscore the need for clinicians to interpret MBSS esophageal findings within the context of patient age, symptom severity, and follow-up testing, rather than relying on MBSS alone for diagnostic conclusions.

Our study has notable limitations that warrant consideration. First, this research was conducted at a tertiary care center specializing in voice and swallowing disorders, where the patient population has a higher proportion of severe dysphagia cases. While this may increase the sensitivity of MBSS in this specific cohort, it limits the generalizability of our findings to broader populations. Nonetheless, by correlating MBSS findings with subsequent esophageal diagnostic studies, our evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of MBSS remains valid within this setting. Second, the retrospective nature of this study introduces inherent biases, including the lack of blinded interpretation of esophageal studies. Clinicians were aware of patients’ clinical histories, potentially influencing diagnostic conclusions. In addition, while our pre-specified power analysis identified a sample size appropriate for our primary outcome—the association between MBSS retention and confirmed esophageal pathology—the number of cases available for subgroup analyses (e.g., Manometry and Anti-Reflux Testing) was substantially smaller (e.g., only 11 cases for reflux monitoring). This limited sample size reduces statistical power and increases the risk of a type II error, potentially obscuring true associations. Future studies, preferable randomized controlled studies with larger subgroup samples will be necessary to validate these findings. Additionally, we were unable to stratify our analysis by specific esophageal pathologies (e.g., achalasia, stenosis) due to limited subgroup sample sizes, which restricted our ability to explore potentially distinct associations with MBSS retention. Furthermore, the rationale for performing multiple esophageal studies in certain patients and the timing of medication initiation relative to MBSS was not always discernible from chart review, reflecting the heterogeneity of clinical practice in dysphagia evaluation. Variability in the interpretation of radiologic studies and GI procedures by multiple clinicians may have further influenced the results. Finally, while data on gastrointestinal medications were collected, the timing of medication initiation relative to MBSS and subsequent studies could not be consistently determined, introducing a potential confounding factor.

This study highlights the broader challenge of managing swallowing disorders, a field fragmented across specialties including SLPs, otolaryngologists, gastroenterologists, and radiologists. These disciplines often operate within disparate diagnostic frameworks, utilizing inconsistent terminology and approaches to treatment. To enhance its utility as a screening method for esophageal dysfunction, there is a pressing need to standardize and validate specific MBSS esophageal protocols and scoring systems[13,20]. While the theoretical inclusion of esophageal phase evaluation in MBSS offers promise, our data suggest that MBSS alone cannot be relied upon as a robust screening tool for esophageal dysphagia. Future efforts should focus on developing standardized methodologies, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and implementing improved diagnostic protocols to enhance the utility of MBSS in this domain.

In conclusion, this study underscores the limitations of the MBSS as a diagnostic tool for esophageal dysphagia, particularly in detecting clinically significant esophageal pathology. While the MBSS offers valuable insight into oropharyngeal swallowing and allows for the visualization of esophageal retention, its diagnostic accuracy for esophageal motility disorders remains insufficient, with notable rates of both false positives and false negatives. Despite the recognition of esophageal phase evaluation as part of the SLP scope of practice, our findings suggest that MBSS alone cannot reliably detect or diagnose esophageal dysphagia. The variability in MBSS interpretation and the lack of standardized protocols further contribute to its limited clinical utility. Moving forward, it is essential to establish comprehensive, evidence-based guidelines for MBSS evaluation and explore more effective diagnostic methodologies to better address the complex nature of swallowing disorders.

| 1. | Patel DA, Krishnaswami S, Steger E, Conover E, Vaezi MF, Ciucci MR, Francis DO. Economic and survival burden of dysphagia among inpatients in the United States. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Paranji S, Paranji N, Wright S, Chandra S. A Nationwide Study of the Impact of Dysphagia on Hospital Outcomes Among Patients With Dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cheng H, Deng X, Li J, Tang Y, Yuan S, Huang X, Wang Z, Zhou F, Lyu J. Associations Between Dysphagia and Adverse Health Outcomes in Older Adults with Dementia in Intensive Care Units: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Interv Aging. 2023;18:1233-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Attrill S, White S, Murray J, Hammond S, Doeltgen S. Impact of oropharyngeal dysphagia on healthcare cost and length of stay in hospital: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Hong I, Bae S, Lee HK, Bonilha HS. Prevalence of Dysphonia and Dysphagia Among Adults in the United States in 2012 and 2022. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2024;33:1868-1879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martin-Harris B, Canon CL, Bonilha HS, Murray J, Davidson K, Lefton-Greif MA. Best Practices in Modified Barium Swallow Studies. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29:1078-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watts S, Gaziano J, Kumar A, Richter J. Diagnostic Accuracy of an Esophageal Screening Protocol Interpreted by the Speech-Language Pathologist. Dysphagia. 2021;36:1063-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Zambito G, Roether R, Kern B, Conway R, Scheeres D, Banks-Venegoni A. Is barium esophagram enough? Comparison of esophageal motility found on barium esophagram to high resolution manometry. Am J Surg. 2021;221:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Serna-Gallegos D, Basseri B, Bairamian V, Pimentel M, Soukiasian HJ. Gastroesophageal reflux reported on esophagram does not correlate with pH monitoring and high-resolution esophageal manometry. Am Surg. 2014;80:1026-9. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Halland M, Ravi K, Barlow J, Arora A. Correlation between the radiological observation of isolated tertiary waves on an esophagram and findings on high-resolution esophageal manometry. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ott DJ, Richter JE, Chen YM, Wu WC, Gelfand DW, Castell DO. Esophageal radiography and manometry: correlation in 172 patients with dysphagia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schima W, Stacher G, Pokieser P, Uranitsch K, Nekahm D, Schober E, Moser G, Tscholakoff D. Esophageal motor disorders: videofluoroscopic and manometric evaluation--prospective study in 88 symptomatic patients. Radiology. 1992;185:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Watts S, Gaziano J, Kumar A, Richter J. The Modified Barium Swallow Study and Esophageal Screening: A Survey of Clinical Practice Patterns. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2023;32:1065-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Reedy EL, Herbert TL, Bonilha HS. Visualizing the Esophagus During Modified Barium Swallow Studies: A Systematic Review. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2021;30:761-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Miles A, Clark S, Jardine M, Allen J. Esophageal Swallowing Timing Measures in Healthy Adults During Videofluoroscopy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:764-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, Castell DO, Schleicher M, Sandidge J, Maxwell R, Blair J. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment--MBSImp: establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008;23:392-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Allen JE, White C, Leonard R, Belafsky PC. Comparison of esophageal screen findings on videofluoroscopy with full esophagram results. Head Neck. 2012;34:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1676] [Cited by in RCA: 2015] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, Levy AD, Carucci LR, Bartel TB, Cash BD, Chang KJ, Feig BW, Fowler KJ, Garcia EM, Kambadakone AR, Lambert DL, Marin D, Moreno C, Peterson CM, Scheirey CD, Smith MP, Weinstein S, Kim DH. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Dysphagia. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:S104-S115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Van Daele DJ. Esophageal Manometry, pH Testing, Endoscopy, and Videofluoroscopy in Patients With Globus Sensation. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:2120-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Watts S, Gaziano J, Jacobs J, Richter J. Improving the Diagnostic Capability of the Modified Barium Swallow Study Through Standardization of an Esophageal Sweep Protocol. Dysphagia. 2019;34:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hawkins D, Cabrera CI, Kominsky R, Nahra A, Howard NS, Maronian N. Dysphagia Evaluation: The Added Value of Concurrent MBS and Esophagram. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:2666-2670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vose AK, Kesneck S, Sunday K, Plowman E, Humbert I. A Survey of Clinician Decision Making When Identifying Swallowing Impairments and Determining Treatment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2018;61:2735-2756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, Lee FS, Walters B. Delayed initiation of the pharyngeal swallow: normal variability in adult swallows. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:585-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gyawali CP, Carlson DA, Chen JW, Patel A, Wong RJ, Yadlapati RH. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Clinical Use of Esophageal Physiologic Testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1412-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gyawali CP, Bredenoord AJ, Conklin JL, Fox M, Pandolfino JE, Peters JH, Roman S, Staiano A, Vaezi MF. Evaluation of esophageal motor function in clinical practice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:99-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Patel DA, Yadlapati R, Vaezi MF. Esophageal Motility Disorders: Current Approach to Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1617-1634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sanagapalli S, Plumb A, Lord RV, Sweis R. How to effectively use and interpret the barium swallow: Current role in esophageal dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35:e14605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Besanko LK, Burgstad CM, Cock C, Heddle R, Fraser A, Fraser RJ. Changes in esophageal and lower esophageal sphincter motility with healthy aging. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2014;23:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Djinbachian R, Marchand E, Yan W, Bouin M. Effects of Age on Esophageal Motility: A High-Resolution Manometry Study. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13:413-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/