INTRODUCTION

Fatty liver disease (FLD) is not new, but its formal recognition and categorization is a relatively recent development (Figure 1). The association of hepatic steatosis with alcohol abuse is a well-known pathological entity with a well-recognized and non-controversial terminology of alcoholic liver disease (ALD). However, nonalcoholic FLD (NAFLD), a historical overarching term used for the spectrum of FLDs not linked to significant alcohol abuse or other known etiologic agents, was formally recognized only in the 1980s[1,2]. Since then, it has been plagued with nomenclature and diagnostic controversies. Its predecessor term, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), was first named by Ludwig et al[3] in 1980. In the seminal report of 20 patients whose liver biopsy specimens exhibited striking fatty and necro-inflammatory changes, Mallory bodies, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, Ludwig et al[3] used the name “NASH” to distinguish it from the well-characterized pathological condition of ALD. The study subjects exhibited a high prevalence of obesity, female gender, type 2 diabetes (T2D), gallstones, and thyroid disease[3]. The broader term NAFLD was first used in a review article by Schaffner and Thaler[4] in 1986. Since these earlier descriptions of FLD, considerable progress has been made in understanding the disease's epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, pathology, treatment, and prognosis[5-10]. During the ensuing years, the prevalence of the disease has risen steeply throughout the world and it has attained epidemic proportions globally affecting more than 30% of the world's adult population. It has also attained the status of the dominant source of chronic liver disease and the dominant indication of liver transplantation globally[11-16]. The rise in prevalence has, in particular, paralleled the rise in the incidence of obesity, T2D, and metabolic syndrome (MS)[17-21]. Several studies also reported an association of the disease with cardiovascular disease, thus further complicating the disease's etiology and pathogenesis[22-25]. Although there is also no specific treatment for the disease to date, considerable progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms of the disease. These advancements have made it possible to develop targeted therapies, paving the way for personalized medicine[26-30]. This huge expansion of knowledge and advancements in understanding the disease were not reflected until very recently either in the nomenclature of the disease or its diagnostic criteria. All the above developments necessitated a revisiting of the terminology and classification of the disease[31,32]. This mini-review aims to summarize the history of nomenclature changes of this disease. This change is not merely a semantic process but has considerable implications not only for hepatologists but for several other stakeholders.

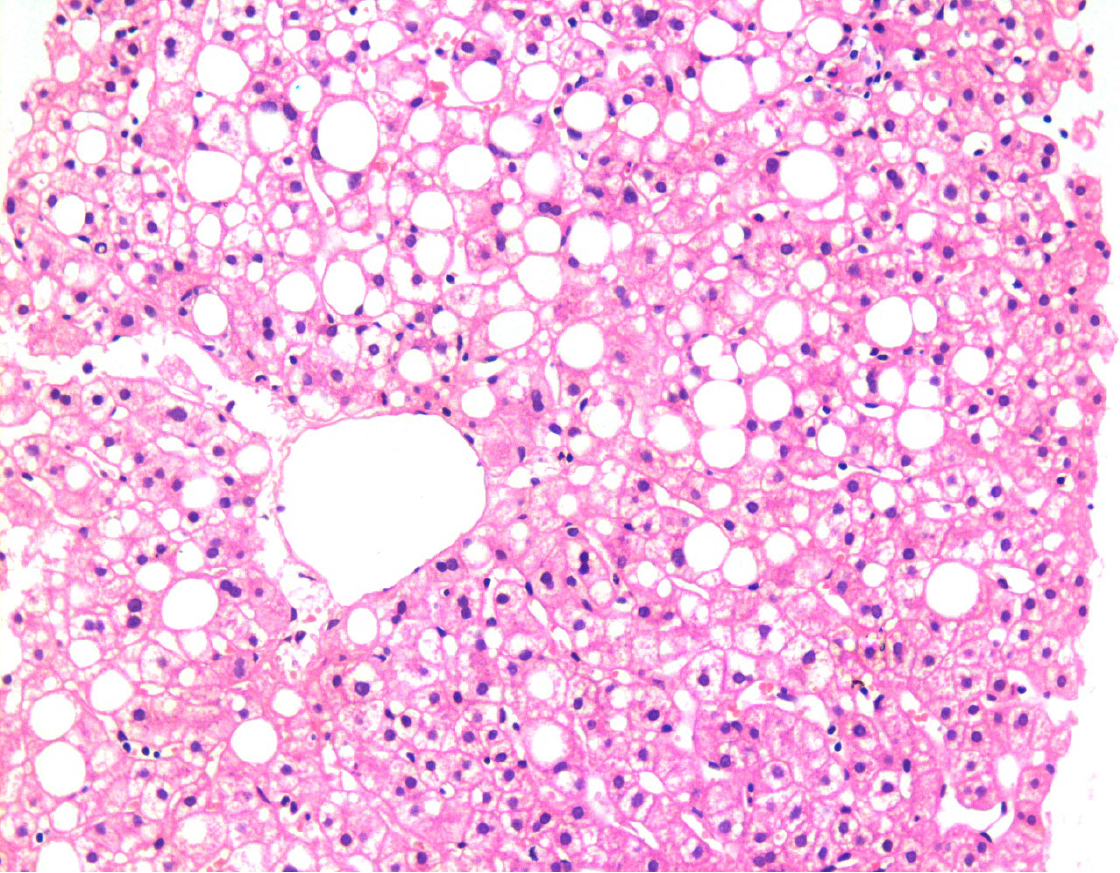

Figure 1 Liver biopsy showing fatty changes.

There is a predominant macro-vesicular fatty change in the centrilobular area. There is no significant hepatocellular damage, inflammation, or fibrosis. This represents one end of the spectrum of fatty diseases of the liver (HE, × 200).

History of nomenclature changes

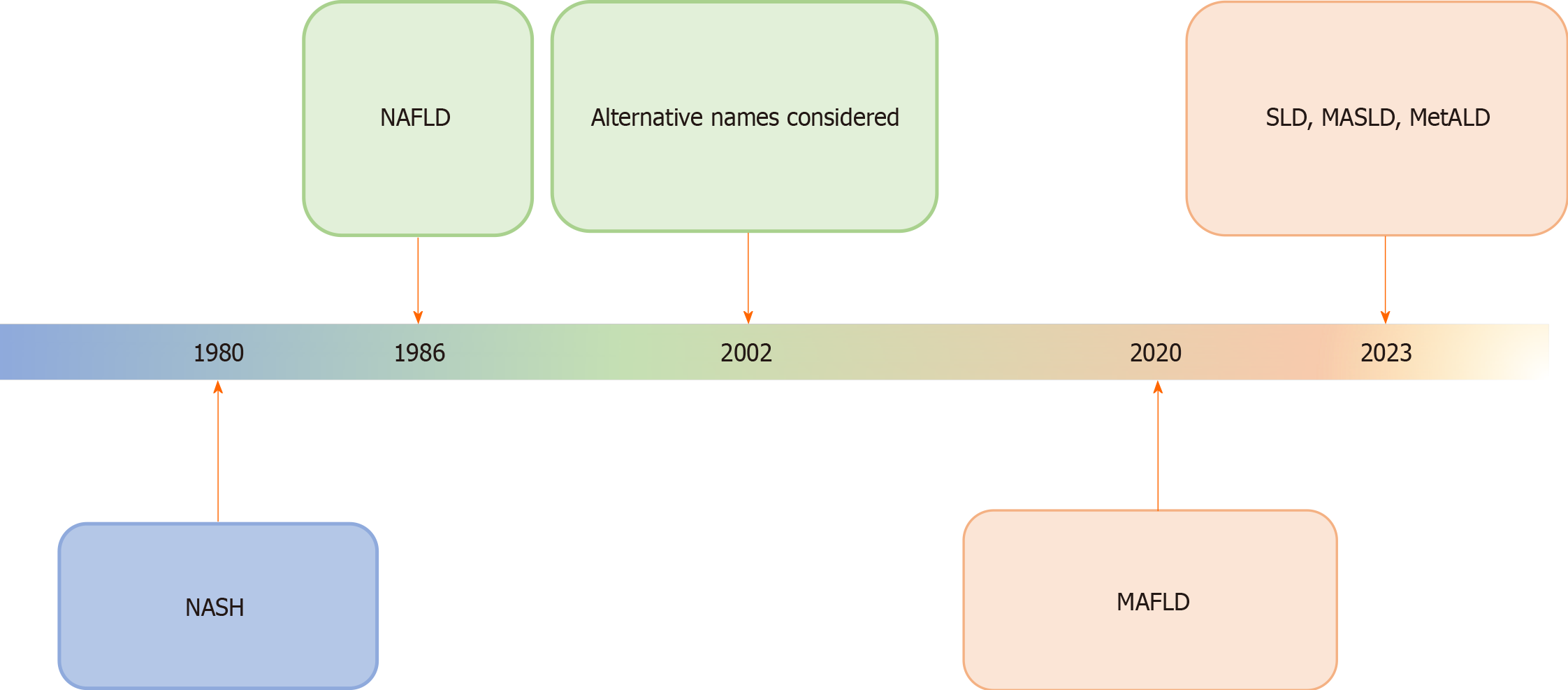

The term NASH was coined almost four decades ago by Ludwig and his colleagues in a seminal paper published in Mayo Proceedings journal[3]. Soon, it became the subject of intense research on multiple aspects of the disease to define its epidemiology, pathogenetic mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Its overarching term, NAFLD, was first used by Schaffner and Thaler[4] in 1986 in a review article on FLDs (Figure 2). With the expansion of knowledge about different aspects of the disease and its widespread prevalence, it was soon realized that the original name does not reflect the continuously expanding knowledge and understanding of the disease's etiology and pathogenesis. Many acquired and genetic risk factors were identified and the heterogeneity and complexity of disease pathogenesis became obvious[33-35]. In a Single Topic Conference on NAFLD held in 2002 and sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), it was hotly debated to change the name of the disease to better reflect the etiopathogenesis of the disease and many alternative names were considered but no one name was approved[31].

Figure 2 Schematic diagram showing the history of evolution of nomenclature changes of fatty liver diseases, particularly, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

The most recent name suggested is the overarching term of steatotic liver disease. The rationalization of classification approaches is highlighted by changes in color. NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; MAFLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated SLD; MetALD: MASLD, and moderate alcohol intake; NAFLLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; SLD: Steatotic liver disease.

The two main objections to the use of the term NAFLD were that it was based on negative or exclusionary diagnostic criteria and there were some stigmatizing terms in the name, i.e., alcohol and fatty[36-40]. There was no link to the underlying etiology or risk factors of the disease in the name. In addition, the previous terminology excluded individuals harboring risk factors for NAFLD, for instance, T2D, who consumed greater quantities of alcohol than the non-alcoholic thresholds envisaged in the criteria.

In 2020, metabolic dysfunction-associated FLD (MAFLD) was proposed as a replacement for the acronym NAFLD by a small number of international liver experts, to emphasize the importance of systemic metabolic dysfunction in the etiopathogenesis of this disease[41,42]. They suggested MAFLD as the single overarching term for the entire spectrum of NAFLD. They also proposed positive diagnostic criteria for an affirmative diagnosis of MAFLD (Figure 2). The change of the terminology of “NAFLD” to “MAFLD” was done to highlight the dominant role of metabolic factors in the disease etiology and pathogenesis, thus improving patient understanding of the disease, facilitating patient-physician communication, and emphasizing the importance of public health interventions in its prevention and management[43-45]. However, the new term still included stigmatizing terms and did not cover the whole spectrum of steatotic liver disease (SLD). Some specific examples of discrepancies include, for example, not all cases of NAFLD are seen in obese or fatty individuals. These can be seen in lean individuals. Fat may not be demonstrated in the liver tissue in advanced stages of SLD resulting in cirrhosis. The new name was accepted by many societies dedicated to the study of liver diseases. Nevertheless, a broader international agreement was not accorded and some of the key pan-national and national societies did not fully endorse the terminology as many other stakeholders. Many liver experts described it as a premature attempt[46,47]. Concerns were also raised on the robustness and transparency of the methodology used for changing the name. They also removed the term steatohepatitis, a key lesion in progressive forms of FLD, from the nomenclature (Figure 3). The heterogeneity of NAFLD etiology and pathophysiology was ignored in MAFLD. In initial clinical trials, investigators concentrated on curtailing metabolic risk factors or insulin resistance, as NAFLD was predominantly thought of as a hepatic expression of the MS. However, most of these clinical trials with anti-obesity treatments, lipid-lowering agents, and insulin sensitizers, did not succeed in NAFLD treatment. The development of NAFLD is mediated by a variety of mechanisms and is much more complicated than formerly stipulated. Thus, a dominant focus on metabolic dysfunction could mask new treatment targets and delay the development of targeted therapeutics. Some important risk factors such as dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota, genetic factors, and sarcopenia, were not given due consideration in the MAFLD transition. However, these factors are important contributory factors in the development of NAFLD and may serve as targets for drug discovery. The new characterization of MAFLD also increased the spectrum of the study population in phase III clinical trials, since it also encompassed subjects with ALD or viral hepatitis. Moreover, the definition of the resolution of MAFLD as the key endpoint in clinical trials could result in controversial results. Presently, the resolution of NASH without augmentation of hepatic fibrosis is utilized as a tangible endpoint in clinical trials for NAFLD[43,44].

Figure 3 Liver biopsy showing morphological changes of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, now named metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis.

There is the macro-vesicular fatty change associated with ballooned hepatocytes (green arrow), inflammation, and fibrosis. A few Mallory bodies are seen in the ballooned hepatocytes (blue arrow). This represents the progressive form of fatty disease of the liver that may progress to cirrhosis if left untreated (HE, × 200).

The new nomenclature

Acknowledging the above deficiencies, a wide-ranging and all-inclusive effort was started by the AASLD, the Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado, and the European Association for the Study of the Liver to systematically and scientifically address this issue. This multi-stakeholder initiative not only involved hepatologists, but also included hepatopathologists, gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, and obesity and public health experts, along with representatives from regulatory agencies, industry, and patient advocacy groups. Their combined expertise and varied viewpoints helped achieve a new agreement on changing the diagnostic criteria and terminology for NAFLD[48].

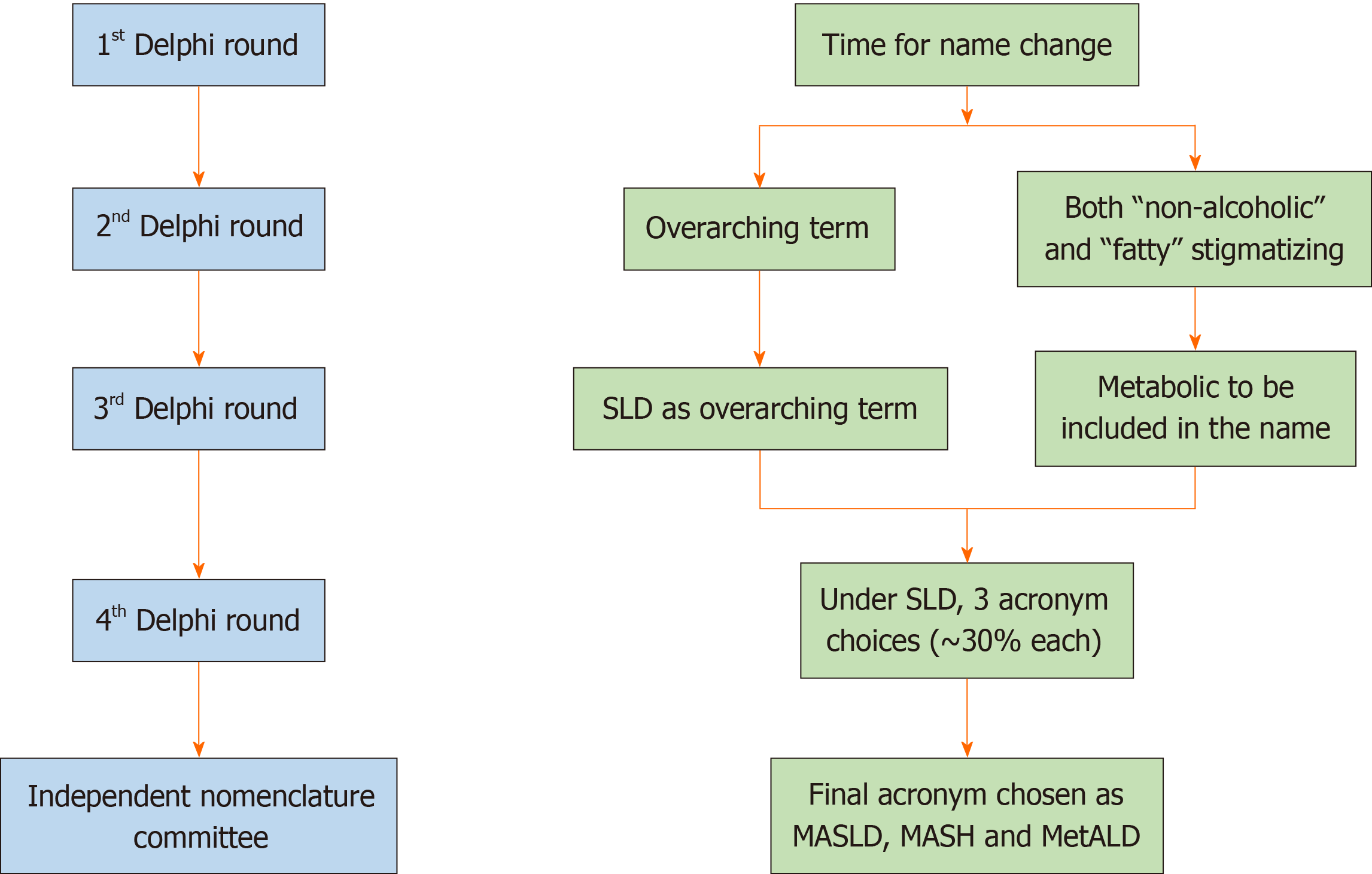

The new nomenclature was developed from 2020 to early 2023 and was finalized in June 2023. The global consultation process used the structured, transparent, multistage survey-based Delphi technique along with hybrid meetings (Figure 4). During the process, a total of 236 panelists from 56 countries, and members of the NAFLD Nomenclature Consensus Group, contributed to four online surveys and two in-person meetings with a final response rate of > 75% for four rounds of data collection. In a preliminary survey, the terms 'non-alcoholic' and 'fatty' were considered to be stigmatizing by 61% and 66% of those who responded, respectively[48]. As the term ‘non-alcoholic’ was already replaced, the term ‘fatty’ was replaced by steatosis, a scientific and non-stigmatizing term. Thus, SLD was selected as an umbrella term to include all possible causes of steatosis including ALD (Figure 5). Five diagnostic sub-categories were created to encompass the entire spectrum of FLDs including ALD and combined forms of the disease. The term steatohepatitis was retained as it was considered to represent a crucial step in the progressive form of liver damage caused by fat accumulation and an integral part of the natural course of the disease. The term metabolic dysfunction-associated SLD (MASLD) was chosen in place of NAFLD. A consensus was also reached on changing the defining criteria. The presence of at least one among the five cardiometabolic risk factors was considered essential for the diagnosis. These are different for adult and pediatric patients. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) was selected to represent the former term NASH. Cases in which no metabolic parameters and no known causes were obvious were categorized as cryptogenic SLD (Figure 5). Because of the frequent concurrence of the two pathologies, a new category, designated MetALD was chosen to represent those patients with MASLD who consume beyond threshold amounts of alcohol per week. The Delphi panel devised an algorithmic approach for categorizing the disease in individual patients (Figure 6), which is very helpful in clinical practice. It should be noted that the name change does not alter the natural history, biomarkers, or trials. The staging and grading of the disease will also not be affected by this change of terminology. The Delphi panel defined and separated a sub-category, MetALD, that has not been studied till now, which will benefit from being included in clinical trials and integrated into care pathways. According to proponents of the new nomenclature, there is a need for more work to be done to enhance disease familiarity, eliminate stigma, and speed up biomarker and targeted drug development to improve outcomes of patients with MASLD and MetALD[48].

Figure 4 Overview of the main methodology used to change the name of fatty liver disease.

The conclusions reached at each round of the Delphi method are shown on the right. Changes were also made in the diagnostic criteria (not shown here). An independent subcommittee comprising expert hepatologists, endocrinologists, pediatricians, and patients chose between the top three acronyms emerging from the fourth Delphi round. SLD: Steatotic liver disease; MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated SLD; MASH: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; MetALD: MASLD, and moderate alcohol intake.

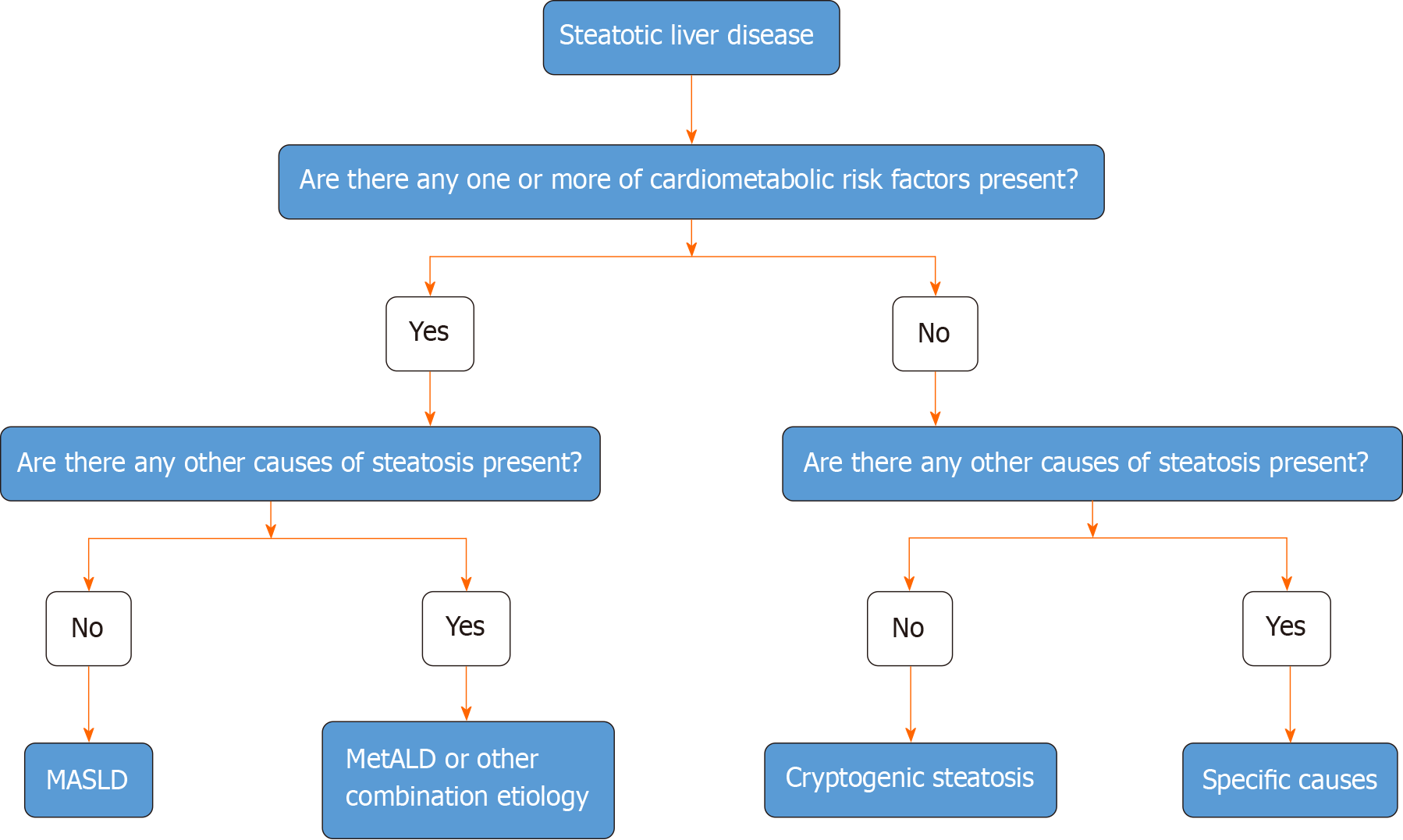

Figure 5 Steatotic Liver Disease and its sub-categorization.

This figure shows the schema for steatotic liver disease (SLD) and its sub-categorization. SLD, diagnosed by imaging studies or histology, has many potential causes. Metabolic dysfunction-associated SLD, defined as hepatic steatosis together with one cardiometabolic risk factor and no other apparent cause, ALD, and an overlap of the two (MetALD), comprise the most common causes of SLD. Other specific causes of SLD need to be considered separately, as they exhibit distinct pathogenesis. Multiple etiologies of steatosis can coexist in one case. Those with no identifiable cause are currently placed under the cryptogenic SLD category. However, these may be reclassified in the future in response to an increase in our understanding of disease pathophysiology. SLD: Steatotic liver disease.

Figure 6 Algorithmic approach to the categorization of steatotic liver disease.

In the presence of hepatic steatosis either on imaging or liver biopsy, the presence of any of a cardiometabolic risk factor (CMRF) will lead to a diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (SLD) in the absence of other causes of hepatic steatosis. If additional causes of steatosis are identified, then this will qualify for a combination etiology. In the case of alcohol, this is labeled MetALD. In the absence of overt CMRF, other causes must be excluded and if none is identified, this is labeled cryptogenic SLD. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated SLD; MetALD: MASLD, and moderate alcohol intake.

Implications and opportunities

The change of name from NAFLD to MASLD has many benefits and implications. It is an affirmative diagnosis with positive diagnostic criteria. It avoids the use of stigmatizing terms. It has been endorsed internationally and is widely accepted. It raises awareness of the disease process and its risk factors in primary care physicians and patients and elucidates treatment options more clearly, and encourages a comprehensive approach to managing patients with the disease. MASLD permits better management of patients with concurrent liver diseases other than MASLD. During the NAFLD era, chronic hepatitis C-infected patients, for example, were labeled as such regardless of the occurrence of liver steatosis. As a result, the significance of lifestyle changes in these patients was underestimated. Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence that concurrent liver steatosis aggravates the outcome in individuals with chronic viral hepatitis. Thus, the new initiative recognizes multiple causes of SLD and allows multidisciplinary management for such patients. The term MASLD underscores metabolic dysfunction as the fundamental mechanism of hepatic steatosis, both through its terminology and the required diagnostic criteria. This change in nomenclature also would facilitate an instinctive elucidation of causes and management options for patients. The metamorphosis of name from NAFLD to MASLD is more than a semantic process and will have implications for research, government policies, the pharmaceutical industry, and insurance companies. The change in name to “MASLD” will require substantial changes in the designs of ongoing clinical trials of NAFLD, their main endpoints, clinical outcomes of final approval, and treatment targets due to the new inclusion criteria[48,49]. The transition to a new nomenclature for the FLD will require a step-by-step methodology to ensure its successful implementation and universal acceptance across the globe. The true implications of the changes in nomenclature and diagnostic criteria will become more obvious as the nomenclature and diagnostic modifications take effect in real life.