Published online Mar 22, 2023. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v14.i2.34

Peer-review started: November 29, 2022

First decision: January 31, 2023

Revised: February 23, 2023

Accepted: March 10, 2023

Article in press: March 10, 2023

Published online: March 22, 2023

Processing time: 111 Days and 16.4 Hours

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is now established as the salvage procedure of choice in patients who have uncontrolled or severe recurrent variceal bleeding despite optimal medical and endoscopic treatment.

To analysis compared the performance of eight risk scores to predict in-hospital mortality after salvage TIPS (sTIPS) placement in patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding after failed medical treatment and endoscopic intervention.

Baseline risk scores for the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, Bonn TIPS early mortality (BOTEM), Child-Pugh, Emory, FIPS, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), MELD-Na, and a novel 5 category CABIN score incorporating Creatinine, Albumin, Bilirubin, INR and Na, were calculated before sTIPS. Concordance (C) statistics for predictive accuracy of in-hospital mortality of the eight scores were compared using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) analysis.

Thirty-four patients (29 men, 5 women), median age 52 years (range 31-80) received sTIPS for uncontrolled (11) or refractory (23) bleeding between August 1991 and November 2020. Salvage TIPS controlled bleeding in 32 (94%) patients with recurrence in one. Ten (29%) patients died in hospital. All scoring systems had a significant association with in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05) on multivariate analysis. Based on in-hospital survival AUROC, the CABIN (0.967), APACHE II (0.948) and Emory (0.942) scores had the best capability predicting mortality compared to FIPS (0.892), BOTEM (0.877), MELD Na (0.865), Child-Pugh (0.802) and MELD (0.792).

The novel CABIN score had the best prediction capability with statistical superiority over seven other risk scores. Despite sTIPS, hospital mortality remains high and can be predicted by CABIN category B or C or CABIN scores > 10. Survival was 100% in CABIN A patients while mortality was 75% for CABIN B, 87.5% for CABIN C, and 83% for CABIN scores > 10.

Core Tip: This study compared the performance of a new CABIN score with seven existing risk scores to predict in-hospital mortality after salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement in 34 patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding after failed medical treatment and endoscopic intervention. Using concordance statistics for predictive accuracy of in-hospital mortality the novel 5 category CABIN score incorporating Creatinine, Albumin, Bilirubin, INR and Na outperformed the APACHE II, BOTEM, Child-Pugh, Emory, FIPS, MELD and MELD-Na scores when compared by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) analysis. Survival was 100% in CABIN A patients while mortality was 75% for CABIN B, 87.5% for CABIN C, and 83% for CABIN scores > 10.

- Citation: Krige J, Jonas E, Robinson C, Beningfield S, Kotze U, Bernon M, Burmeister S, Kloppers C. Novel CABIN score outperforms other prognostic models in predicting in-hospital mortality after salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2023; 14(2): 34-45

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v14/i2/34.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v14.i2.34

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is now established as the salvage procedure of choice in patients who have uncontrolled or severe recurrent variceal bleeding despite optimal medical and endoscopic treatment[1]. Key clinical distinctions exist in the spectrum of patients undergoing TIPS, ranging from high-risk cirrhotic patients with liver decompensation and uncontrolled variceal bleeding necessitating an emergent salvage TIPS (sTIPS) to those with well-preserved liver function undergoing an elective TIPS for refractory bleeding. Current risk stratification of patients who have refractory variceal bleeding and require sTIPS is however imperfect. Although TIPS is a minimally invasive procedure, appropriate patient selection is crucial to identify patients who would benefit from the procedure, considering the substantial risks of hepatic encephalopathy, liver failure and increased overall morbidity and mortality in high-risk individuals[2,3].

Several prognostic and risk scores have been developed to identify patients at risk for a poor clinical outcome after sTIPS. These include the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II[4], Bonn TIPS early mortality (BOTEM)[5], Child-Pugh (C-P)[6], Emory[7], Freiburg index of post-TIPS survival (FIPS)[8], model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)[9], and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease sodium (MELD-Na)[10] scores. In this study the accuracy of a novel CABIN score, which was developed to overcome limitations of existing scoring systems, was compared to established risk scores for the prediction of in-hospital mortality following sTIPS.

In this retrospective observational analysis, eight risk scores were evaluated in a cohort which included all adult patients who underwent sTIPS for uncontrollable or life-threatening refractory variceal bleeding in the Surgical Gastroenterology Unit at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town Private Academic Hospital between August 1991 and November 2020. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies[11]. Baseline demographic, clinical and endoscopic data and bio

| Variable | Total cohort (n = 34) | Survived (n = 24) | In-hospital death (n = 10) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 52 ± 11.6 | 50 ± 10.5 | 57 ± 12.9 | 0.107 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 29 (85) | 22 (92) | 7 (70) | 0.104 |

| Female | 5 (15) | 2 (8) | 3 (30) | |

| Cause of cirrhosis | ||||

| Alcohol related | 22 (65) | 15 (63) | 7 (70) | 0.938 |

| Non-alcohol related | 12 (35) | 9 (37) | 3 (30) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 3 (9) | 3 (12) | 0 | 0.022 |

| B | 19 (56) | 16 (67) | 3 (30) | |

| C | 12 (35) | 5 (20) | 7 (70) | |

| Risk prediction scores | ||||

| APACHE II (mean ± SD) | 13.4 ± 4.7 | 11.4 ± 3.3 | 18.3 ± 3.8 | 0.196 |

| BOTEM (mean ± SD) | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 0.964 |

| CABIN (mean ± SD) | 10.9 ± 5.0 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 17.0 ± 3.8 | 0.133 |

| CHILD-PUGH (mean ± SD) | 8.9 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 1.8 | 10.6 ± 2.0 | 0.001 |

| EMORY (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 0.497 |

| FIPS (mean ± SD) | -0.3 ± 0.9 | -0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.205 |

| MELD (mean ± SD) | 15.0 ± 6.2 | 13 ± 4.8 | 19.8 ± 6.7 | 0.007 |

| MELD-Na (mean ± SD) | 16.9 ± 7.4 | 14 ± 5.3 | 23.9 ± 7.1 | < 0.001 |

Details of the acute bleeding management protocol and the endoscopic interventional techniques used in our unit have been published previously[12-15]. In patients who had endoscopically uncontrolled bleeding a Minnesota balloon tube or a Danis esophageal stent (Ella-CS, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic) was inserted to tamponade variceal bleeding and endotracheal intubation was used for airway protection when indicated[16]. In this high-risk group with uncontrolled variceal bleeding and those with refractory life-threatening bleeding despite endoscopic intervention and somatostatin infusion, sTIPS was performed as an emergency procedure under general anaesthesia with placement of an expandable uncovered 10 mm Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States)[15].

The study protocol followed the Baveno recommendations and defined uncontrolled or persistent variceal bleeding as the need for a transfusion of 4 units of blood or more within 6 h and the inability to achieve an increase in systolic blood pressure to 70 mmHg or more or a pulse reduction to less than 100/min. Contraindications to sTIPS in our unit were severe pulmonary hypertension, severe tricuspid regurgitation, congestive heart failure, fibropolycystic liver disease, uncontrolled systemic sepsis and unrelieved biliary obstruction. Relative contraindications were congenital hepatic fibrosis, portal vein thrombosis, obstruction of all hepatic veins and severe coagulopathy (INR > 5).

Details of the newly developed five component CABIN score are given in Supplementary Table 1. Each CABIN variable is scored from one to five and the cumulative total is calculated by adding the individual values of the five biochemical components (Creatinine, Albumin, Bilirubin, INR (international normalized ratio) and Na (sodium). The best total CABIN score computes at 5 points and the worst at 25 points. Four CABIN categories (A-D) were established (A: 5-10 points, B: 11-15, C: 16-20, D: 21-25).

The CABIN score and seven previously described scoring systems, APACHE II, BOTEM, Child-Pugh, Emory, FIPS, MELD, and MELD-Na scores were calculated based on clinical evaluation and laboratory values obtained before the sTIPS procedure. The primary study outcome measure was prediction of in-hospital mortality after sTIPS and compared the relative performances of the seven established scoring models and the new CABIN score.

All clinical data and variables were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capturing software licensed to the University of Cape Town[17]. Statistical computations were made using IBM SPSS statistics (version 26.0, IBM, United States). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Continuous data were reported as mean ± SD or medians and range and discrete data as percentages. To evaluate the performance of the various scoring systems to predict in-hospital mortality the concordance C-statistic [area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves] was used.

The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Ref No. 120/2019) of the University of Cape Town and the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 564 patients with variceal bleeding were treated during the study period. In 530 patients (94%), bleeding was controlled by endoscopic intervention and medication. In 34 patients (6%) who constitute the study population and underwent sTIPS, bleeding was either uncontrollable ab initio (n = 11) or life-threatening refractory (n = 23) despite optimal endoscopic and pharmacological management.

The demographic and clinical data of the patients are summarized in Table 1. No patients had a concomitant HCC or portal vein thrombosis at the time of TIPS insertion. Before sTIPS 19 patients had a median of three (1-9) injection sclerotherapy treatment (IST) sessions and 20 had a median of two (1-6) endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) sessions with a median of 10 bands placed per session. Five patients had both IST and EVL. Median units of blood transfused before sTIPS was six (3-12), and 14 patients required either Minnesota balloon tamponade (n = 12) or placement of a Danis stent (n = 2) for temporarily control of bleeding before the sTIPS procedure. Eleven patients required endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation and nine required inotropic support.

Technical success for sTIPS was 100% and therapeutic success (control of bleeding) was achieved in 31 of 34 (91%) patients. Bleeding persisted in two patients (6%) despite a patent sTIPS on repeat US-doppler examination and one patient developed recurrent bleeding in hospital during the index admission after initial control of bleeding by sTIPS.

Ten patients (29.4%) died in hospital at a median of 5 d following the procedure (range 1-10 d) of progressive liver failure (n = 4), MOF (2), alcoholic cardiomyopathy (n = 2) or uncontrolled variceal bleeding (n = 2). Mortality in C-P grade A patients was 0%, in C-P grade B patients 16% and C-P grade C patients 58%. In patients who died the median C-P score was 11, (range 7-13), median MELD score was 18 (range 11-29) and median MELD Na score was 25 (range 11-33). Nine of the 12 (75%) patients who required pre-sTIPS balloon tamponade died, while all nine (100%) patients who were hypotensive (systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg) and with the combination of > 8 unit blood transfusion, inotropic support, balloon tamponade and mechanical ventilation died.

The two patients with persistent bleeding after TIPS underwent repeat endoscopy and ultrasound-guided Histoacryl and coil injection of residual gastric varices with resolution. The patient with recurrent bleeding in hospital underwent a gastric devascularization for control of gastric varices.

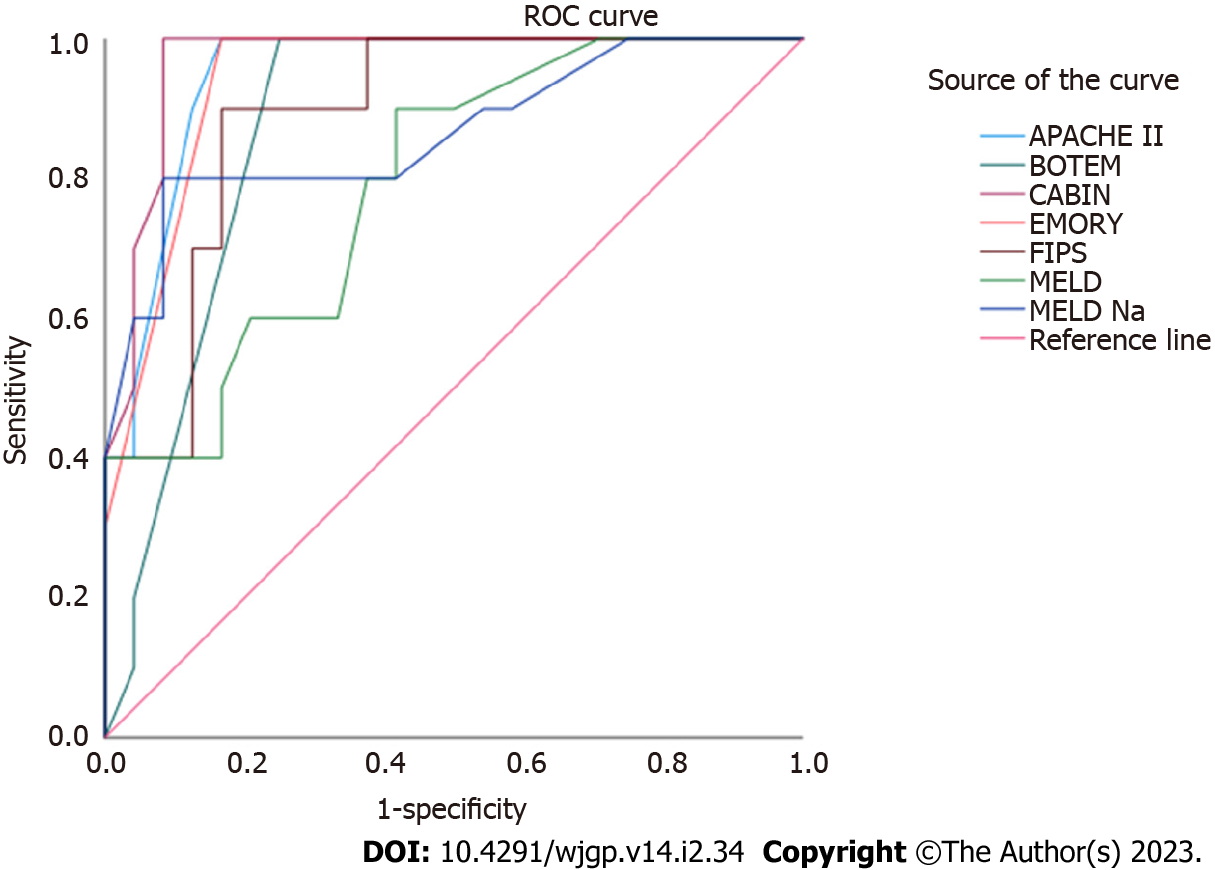

Figure 1 shows the graphic representation of the comparative performances of the eight risk scores in predicting in-hospital death following sTIPS. The CABIN score (AUROC 0.967) had the highest discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital death compared to the APACHE II (AUROC 0.948), BOTEM (AUROC 0.877), C-P (AUROC 0.802), EMORY (AUROC 0.942), FIPS (AUROC 0.892), MELD (AUROC 0.792), and MELD-Na (AUROC 0.865) scores as detailed in Table 2. The median CABIN score in the 24 in-hospital TIPS survivors was 8 (range 5-18) compared to a median of 17 (range 11-22) in the 10 deaths. CABIN A patients had a 100% survival, compared to 25% and 12.5% survival in CABIN B and CABIN C category patients respectively. CABIN points of 11 or more provided a clear survival cut-off. No patients with CABIN scores < 10 died while 83% of patients with CABIN scores of > 11 died.

| In-hospital deaths | ||||

| AUC | STD error | P value | 95% confidence interval | |

| APACHE II | 0.948 | 0.035 | 0 | 0.879–1.000 |

| BOTEM | 0.877 | 0.059 | 0.001 | 0.762–0.992 |

| CABIN | 0.967 | 0.028 | 0 | 0.912–1.000 |

| CHILD-PUGH | 0.802 | 0.084 | 0.006 | 0.638–0.967 |

| EMORY | 0.942 | 0.038 | 0 | 0.868–1.000 |

| FIPS | 0.892 | 0.055 | 0 | 0.783–1.000 |

| MELD | 0.792 | 0.082 | 0.008 | 0.631–0.952 |

| MELD Na | 0.865 | 0.077 | 0.001 | 0.713–1.000 |

The unique safety profile and minimally invasive characteristics conferred by TIPS provide an effective reduction in portal pressure and make the procedure the ideal rescue intervention for variceal bleeding not controlled by endoscopic intervention and pharmacological therapy[18]. In this study we compared the relative performances of eight scoring models, including the novel CABIN score, in predicting in-hospital mortality in a high-risk cohort of patients who underwent sTIPS placement. Although sTIPS controlled variceal bleeding in 94% of patients, over-all in-hospital mortality was 29.4% and increased exponentially in those who required > 8 unit blood transfusion, inotropic support, esophageal balloon tamponade and mechanical ventilation. Log-rank comparisons of survival curves showed that of the eight scores evaluated, the CABIN, APACHE II and Emory scores had the highest AUROC values and the best discriminatory ability with C-statistic values all exceeding 0.9. Of these three top contenders, the CABIN score (0.967) had the best discriminatory and predictive capability. As a collorary, this study also demonstrates the predictive ability of the CABIN score with 100% survival observed in patients in the CABIN A category (< 10 points) after sTIPS.

The reported mortality rate after TIPS placement varies widely due to differing inclusion criteria, timing of TIPS placement, the spectrum and severity of the underlying liver disease and inclusion in some reports of patients with active bleeding during urgent TIPS as well as stable patients undergoing elective TIPS[19-21]. In the 22 studies exclusively reporting salvage or rescue TIPS in patients with uncontrolled life-threatening or endoscopically unmanageable variceal bleeding, as in this study, in-hospital mortality rates range from 17% to 56% which are significantly higher than for elective TIPS[22-43] (Table 3). Accurate prediction of outcome following sTIPS is thus a crucial element of management and the optimal prognostic score should ideally be able to distinguish two groups, patients with a better prognosis and likely to survive and those with a high or prohibitive risk of death.

| Ref. | Country | No. of patients | C-P grade A/B/C | Initial control of bleeding % | 30-d mortality % | Persistent/Recurrent rebleeding | Survival % | Prognostic factors |

| Azoulay et al[22], 2001 | France | 58 | 3/8/47 | 90 | 29 | 17 | 51.7 (12 mo) | Sepsis, vasoactive drugs, balloon tamponade |

| Bañares et al[23], 1998 | Spain | 56 | 11/22/23 | 95 | 28 | 22 (1 mo) | 72 (30 d) | Ascites, HE, albumin |

| Barange et al[24], 1999 | France | 32 | 3/14/15 | 90 | 25 | 14 | 75 (30 d) | ND |

| Bizollon et al[25], 2001 | France | 28 | 0/11/17 | 96 | 25 (40 d) | 18 | 52 (2 yr) | ↑Creatinine, ↑bilirubin |

| Casadaban et al[26], 2015 | United States | 101 | 2/46/52 | 89 | 31 | 21 | 44 (12 mo) | ↑Bilirubin, ↑creatinine, ↑INR, non-alcoholic liver disease |

| Chau et al[27], 1998 | England | 84 | 4/17/63 | 98 | 34 | 30 (30 d) | 66 (30 d) | ND |

| Encarnacion et al[28], 1995 | United States | 64 | 2/32/31 | 98 | 19 | 29 (6 mo) | 56 (12 mo) | Haemodynamic instability |

| Gazzera et al[29], 2012 | Italy | 82 | ND | 94 | 25.6 | 13.4 | 74.4 (30d) | Child-Pugh C, ↑creatinine, ↑PT |

| Gerbes et al[30], 1998 | Germany | 11 | 91 | 27 | 27 | 73 (12 mo) | ND | |

| Helton et al[31], 1993 | United States | 23 | 0/15/18 | 74 | 56 (in hospital) | 39 | ND | Emergency TIPS, active bleeding |

| Hermie et al[32], 2018 | Belgium | 32 | ND/ND/14 | 97 | 31 | 0 | 69 | MELD > 19, Haemodynamic instability |

| Jabbour et al[33], 1996 | United States | 25 | ND/ND/8 | 96 | 44 | ND | 56 (30 d) | Child-Pugh C, urgent TIPS |

| Jalan et al[34], 1995 | Scotland | 19 | 3/3/13 | 100 | 42 | 15.6 | 58 (30 d) | Liver failure, sepsis |

| Maimone et al[36], 2019 | England | 144 | 11/55/78 | ND | 36 (6 wk) | 29 | 64 (6 wk) | ↑MELD, ↑Child-Pugh score |

| Le Moine et al[35], 1994 | Belgium | 24 | 3/13/9 | 96 | 17 | 25 | 29 (5 mo) | ND |

| McCormick et al[37], 1994 | England | 20 | 1/7/12 | 100 | 60 (40 d) | 40 | 30 | ND |

| Patch et al[38], 1998 | England | 54 | 5/20/29 | 91 | 48 (6 wk) | 11 | 53 (6 mo) | Ventilation, ↑WBC, platelets, ↑creatinine |

| Rubin et al[39], 1995 | United States | 49 | 3/23/23 | 84 | 40% | 16 | ND | C-P grade C, APACHE II > 18 |

| Sanyal et al[40], 1996 | United States | 30 | 1/7/22 | 100 | 37 | 7 | 60 (6 wk) | > 70 yr, bilirubin >6 mg/dL, creatinine > 3 mg/dL, HE, ARDS |

| Tyburski et al[41], 1997 | United States | 33 | 0/5/28 | ND | 27 | 15 | 58 (12 mo) | Albumin < 2.5 g/dL, bilirubin > 3 mg/dL, PT > 15 s |

| Tzeng et al[42], 2009 | Taiwan | 107 | ND | ND | 28 | ND | 50 (12 mo) | C-P score > 11, MELD > 20 |

| Zhu et al[43], 2019 | China | 58 | 5/36/7 | 91.2 | 12.3 (6 wk) | 10.5 (6 wk) | 81.8 (12 mo) | Ventilation, ICU |

Most of the current prognostic scores used in sTIPS patients have intrinsic limitations due to the selection and weighting of the constituent components. The MELD score, which was initially created to predict survival following elective placement of TIPS, is currently the most widely used liver-related prognostic score both in clinical practice and research and especially as a tool for organ allocation[9]. Although the MELD score was a prospectively developed and validated indicator of the severity of end-stage liver disease that utilizes quantitative and objective measures, including bilirubin, creatinine and INR values, the score has potential limitations. A further caveat is the maximum assigned value of serum creatinine which is capped at four even when the measured serum level is higher. Modifications to overcome MELD shortcomings have included reweighting the model's coefficients, altering the laboratory components and the addition of new variables including serum sodium (‘MELD-Na’), albumin [termed ‘5-variable MELD’ (5vMELD)][44] and female gender (MELD 3.0)[45]. These modifications are more discriminative than either MELD or MELD-Na in transplant assessment and use similar elements as the CABIN score.

The inclusion of subjective clinical components in other proposed prognostic models may also limit precision and reproducibility of score assignments. The C-P, Emory and BOTEM scores all have at least one component that may be perceived as subjective while the APACHE II and BOTEM scores lack specificity for liver disease which limits their capacity to predict outcomes after liver interventions such a sTIPS. In addition the C-P, Emory, and BOTEM scores are limited by a ceiling effect in which laboratory values above a particular cut-off level are not distinguished from one another in terms of higher scoring[4-7,9,10]. The FIPS overcomes some of these limitations by using four objective components, age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine levels[8].

In a meta-analysis, which included 11 studies and 2037 patients Zhou et al[46] found that MELD was superior to the C-P score in predicting 3-mo survival after TIPS but not 1-mo, 6-mo or 12-mo survival. Zhang et al[47] found that C-P grade C and MELD > 10 but not the Emory, BOTEM or SB/PLT scores were predictors of survival in Chinese cirrhotic patients treated with TIPS. Gaba et al[48] reported that MELD and MELD-Na scores had the best capability to predict early mortality in an American population compared with bilirubin and the C-P, Emory, PI, APACHE II, and BOTEM scores. In a comparison of the MELD, C-P and Emory scores Schepke et al[49] found that all three models predicted 3-mo survival with similar accuracy, but the MELD score was marginally superior to the C-P score for both 12- and 36-mo survival. In patients with refractory variceal bleeding Rubin et al[39] found that survival was inversely proportional to C-P class and APACHE II scores. The single determinant most closely associated with decreased survival in the first month following TIPS was the APACHE II score, with a score of 18 stratifying patients into low and high mortality risk groups (Table 3). Only one of 13 patients with C-P class C cirrhosis and an APACHE II score exceeding 18 survived > 30 d[39]. In the Hermie study early mortality was associated with a MELD score of at least 19 and hemodynamic instability at the time of admission[32] (Table 3). If hemodynamic instability was combined with a high MELD score, the 6-week mortality peaked at 77.8%[32]. In a multicentre French study Walter et al[50] reported that sTIPS mortality was > 90% in patients who had lactate levels ≥ 12 mmol/L and/or a MELD score ≥ 30.

In view of these differing outcomes, the development of a prognostic model to accurately stratify the risk profile of patients undergoing sTIPS may be invaluable in guiding treatment. The novel CABIN score used in this study was developed as a point-based tool to improve prognostic prediction specifically for patients undergoing emergent sTIPS and circumvents the complex computations of the MELD and other scores. This new score avoids subjective elements and can be calculated at the bedside providing a refined, granular grading system from a minimal laboratory dataset with scores ranging from 5 to 25. The CABIN score achieved significant prognostic discrimination reflected by in-hospital survival of 100% in patients in the CABIN A category (5-10 points), while patients in the CABIN B category (11-15) score had a 25% and those in the CABIN C category (16-20) a 12.5% survival. Our model predicted in-hospital mortality with high accuracy and showed statistical superiority over the other seven contenders, including MELD and C-P scores. Moreover, of all the examined models, only the CABIN, APACHE II and Emory scores exceeded a C-statistic value of 0.9.

There are inevitable and specific limitations to our study. Firstly, this investigation is limited by its small sample size, retrospective design, and lack of a control group. Secondly, the study has a clear selection bias which restricts universal applicability as these patients were treated in a single, well-resourced tertiary care referral center with round the clock skilled endoscopic and TIPS access. Thirdly, because patients were accrued over three decades, technical differences in TIPS placement and improvements in medical care during the study period would have contributed to differences in clinical outcomes over time. Fourthly, this new score has been developed using a derivation dataset and requires confirmation and external validation in a similar sTIPS patient group. The robustness of this study is enhanced by the prospective data collection, supervision by the same investigators during the study period, restriction of subjects to a well-defined cohort of cirrhotic patients with uncontrolled exsanguinating bleeding and complete follow-up. The use of all-cause mortality as the primary outcome provided a consistent and objective end point.

In conclusion, the novel CABIN prognostic score, which is objective, quantitative, and reproducible, combines five easily obtained laboratory test results and provides improved statistical power predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding undergoing sTIPS. The CABIN score identified high-risk patients and outperformed other scoring systems in predicting in-hospital mortality. Despite the fact that mortality was 75% for CABIN B, 87.5% for CABIN C, and 83% for CABIN scores > 10 in this study, this high-risk category should not be denied consideration for an emergency TIPS and should be assessed on a case-by-case basis especially in units where there is prompt access to liver transplantation after sTIPS. This study was based on a small defined cohort of predominantly alcoholic decompensated cirrhotic patients undergoing emergent TIPS and this newly developed derivative CABIN score will need further prospective external validation before being considered for general clinical application.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is now established as the salvage procedure of choice in patients who have uncontrolled or severe recurrent variceal bleeding despite optimal medical and endoscopic treatment.

Although TIPS is a minimally invasive procedure, appropriate patient selection is crucial to identify patients who would benefit from the procedure, considering the substantial risks of hepatic encephalopathy, liver failure and increased overall morbidity and mortality in high-risk individuals.

In this study the accuracy of a novel CABIN score, which was developed to overcome limitations of existing scoring systems, was compared to established risk scores for the prediction of in-hospital mortality following sTIPS.

Eight risk scores were evaluated in a cohort which included all adult patients who underwent sTIPS for uncontrollable or life-threatening refractory variceal bleeding. A new five component CABIN score was devised in which each CABIN variable was scored from one to five and the cumulative total is calculated by adding the individual values of the five biochemical components (Creatinine, Albumin, Bilirubin, INR (international normalized ratio) and Na (sodium). The best total CABIN score computes at 5 points and the worst at 25 points. Four CABIN categories (A-D) were established (A: 5-10 points, B: 11-15, C: 16-20, D: 21-25). The CABIN score and seven previously described scoring systems, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, Bonn TIPS early mortality (BOTEM), Child-Pugh, Emory, FIPS, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD), and MELD-Na scores were calculated based on clinical evaluation and laboratory values obtained before the sTIPS procedure. The primary study outcome measure was prediction of in-hospital mortality after sTIPS and compared the relative performances of the seven established scoring models and the new CABIN score.

In 34 patients (6%) who underwent sTIPS, bleeding was either uncontrollable ab initio (n = 11) or life-threatening refractory (n = 23) despite optimal endoscopic and pharmacological management. Ten patients (29.4%) died in hospital at a median of 5 d following the procedure (range 1-10 d). Nine of the 12 (75%) patients who required pre-sTIPS balloon tamponade died, while all nine (100%) patients who were hypotensive (systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg) and with the combination of > 8 unit blood transfusion, inotropic support, balloon tamponade and mechanical ventilation died. The CABIN score [area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) 0.967] had the highest discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital death compared to the APACHE II (AUROC 0.948), BOTEM (AUROC 0.877), C-P (AUROC 0.802), EMORY (AUROC 0.942), FIPS (AUROC 0.892), MELD (AUROC 0.792), and MELD-Na (AUROC 0.865) scores. The median CABIN score in the 24 in-hospital TIPS survivors was 8 (range 5-18) compared to a median of 17 (range 11-22) in the 10 deaths. CABIN A patients had a 100% survival, compared to 25% and 12.5% survival in CABIN B and CABIN C category patients respectively. CABIN points of 11 or more provided a clear survival cut-off. No patients with CABIN scores < 10 died while 83% of patients with CABIN scores of > 11 died.

The novel CABIN prognostic score, which is objective, quantitative, and reproducible, combines five easily obtained laboratory test results and provides improved statistical power predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding undergoing sTIPS. The CABIN score identified high-risk patients and outperformed other scoring systems in predicting in-hospital mortality. Despite the fact that mortality was 75% for CABIN B, 87.5% for CABIN C, and 83% for CABIN scores > 10 in this study, this high-risk category should not be denied consideration for an emergency TIPS and be assessed on a case by case basis especially in units where there is prompt access to liver transplantation after sTIPS.

This study was based on a small defined cohort of predominantly alcoholic decompensated cirrhotic patients undergoing emergent TIPS and this newly developed derivative CABIN score will need further prospective external validation before being considered for general clinical application.

| 1. | Rajesh S, George T, Philips CA, Ahamed R, Kumbar S, Mohan N, Mohanan M, Augustine P. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhosis: An exhaustive critical update. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5561-5596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pandhi MB, Kuei AJ, Lipnik AJ, Gaba RC. Emergent Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Creation in Acute Variceal Bleeding. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2020;37:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bettinger D, Thimme R, Schultheiß M. Implantation of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): indication and patient selection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10902] [Cited by in RCA: 11366] [Article Influence: 277.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brensing KA, Raab P, Textor J, Görich J, Schiedermaier P, Strunk H, Paar D, Schepke M, Sudhop T, Spengler U, Schild H, Sauerbruch T. Prospective evaluation of a clinical score for 60-day mortality after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt: Bonn TIPSS early mortality analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5490] [Cited by in RCA: 5821] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Chalasani N, Clark WS, Martin LG, Kamean J, Khan MA, Patel NH, Boyer TD. Determinants of mortality in patients with advanced cirrhosis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bettinger D, Sturm L, Pfaff L, Hahn F, Kloeckner R, Volkwein L, Praktiknjo M, Lv Y, Han G, Huber JP, Boettler T, Reincke M, Klinger C, Caca K, Heinzow H, Seifert LL, Weiss KH, Rupp C, Piecha F, Kluwe J, Zipprich A, Luxenburger H, Neumann-Haefelin C, Schmidt A, Jansen C, Meyer C, Uschner FE, Brol MJ, Trebicka J, Rössle M, Thimme R, Schultheiss M. Refining prediction of survival after TIPS with the novel Freiburg index of post-TIPS survival. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1362-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1967] [Cited by in RCA: 2106] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Biggins SW, Kim WR, Terrault NA, Saab S, Balan V, Schiano T, Benson J, Therneau T, Kremers W, Wiesner R, Kamath P, Klintmalm G. Evidence-based incorporation of serum sodium concentration into MELD. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1652-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 13603] [Article Influence: 715.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 12. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Bornman PC, Shaw JM, Klipin M. Variceal recurrence, rebleeding, and survival after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in 287 alcoholic cirrhotic patients with bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 2006;244:764-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Krige J, Spence RT, Jonas E, Hoogerboord M, Ellsmere J. A New Recalibrated Four-Category Child-Pugh Score Performs Better than the Original Child-Pugh and MELD Scores in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Decompensated Alcoholic Cirrhotic Patients with Acute Variceal Bleeding: a Real-World Cohort Analysis. World J Surg. 2020;44:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krige JEJ, Bornman PC. Endoscopic therapy in the management of esophageal varices: injection sclerotherapy and variceal ligation. In: Blumgart L (ed) Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, 4th Edition, Saunders, Elsevier, Philadelphia. 2007: 1579-1593. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Krige JEJ, Thomson SR. Endoscopic therapy in the management of esophageal varices. In: Fischer. (Ed) Mastery of Surgery, 7th Edition. Lippincott, Williams, Wilkens. Philadelphia. 2019: 1384–1398. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Krige JEJ, Perold L, Jonas EG. Balloon tube tamponade for variceal bleeding: ten rules for safe usage. S Afr J Surg. 2021;59:198-199. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38562] [Cited by in RCA: 40092] [Article Influence: 2358.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | García-Pagán JC, Saffo S, Mandorfer M, Garcia-Tsao G. Where does TIPS fit in the management of patients with cirrhosis? JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Loffroy R, Favelier S, Pottecher P, Estivalet L, Genson PY, Gehin S, Krausé D, Cercueil JP. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for acute variceal gastrointestinal bleeding: Indications, techniques and outcomes. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:745-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vizzutti F, Schepis F, Arena U, Fanelli F, Gitto S, Aspite S, Turco L, Dragoni G, Laffi G, Marra F. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): current indications and strategies to improve the outcomes. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15:37-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ni JB, Xiang XX, Wu W, Chen SY, Zhang F, Zhang M, Peng CY, Xiao JQ, Zhuge YZ, Zhang CQ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients treated with a balloon tamponade for variceal hemorrhage without response to high doses of vasoactive drugs: A real-world multicenter retrospective study. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:236-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Azoulay D, Castaing D, Majno P, Saliba F, Ichaï P, Smail A, Delvart V, Danaoui M, Samuel D, Bismuth H. Salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for uncontrolled variceal bleeding in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35:590-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bañares R, Casado M, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Camúñez F, Matilla A, Echenagusía A, Simó G, Piqueras B, Clemente G, Cos E. Urgent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for control of acute variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:75-79. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Barange K, Péron JM, Imani K, Otal P, Payen JL, Rousseau H, Pascal JP, Joffre F, Vinel JP. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of refractory bleeding from ruptured gastric varices. Hepatology. 1999;30:1139-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bizollon T, Dumortier J, Jouisse C, Rode A, Henry L, Boillot O, Valette PJ, Ducerf C, Souquet JC, Baulieux J, Paliard P, Trepo C. Transjugular intra-hepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory variceal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:369-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Casadaban LC, Parvinian A, Zivin SP, Lakhoo J, Minocha J, Knuttinen MG, Ray CE Jr, Bui JT, Gaba RC. MELD score for prediction of survival after emergent TIPS for acute variceal hemorrhage: derivation and validation in a 101-patient cohort. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chau TN, Patch D, Chan YW, Nagral A, Dick R, Burroughs AK. "Salvage" transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: gastric fundal compared with esophageal variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Encarnacion CE, Palmaz JC, Rivera FJ, Alvarez OA, Chintapalli KN, Lutz JD, Reuter SR. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement for variceal bleeding: predictors of mortality. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:687-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gazzera C, Righi D, Doriguzzi Breatta A, Rossato D, Camerano F, Valle F, Gandini G. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): results, complications and predictors of mortality in the first month of follow-up. Radiol Med. 2012;117:46-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gerbes AL, Gülberg V, Waggershauser T, Holl J, Reiser M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for variceal bleeding in portal hypertension: comparison of emergency and elective interventions. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2463-2469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Helton WS, Belshaw A, Althaus S, Park S, Coldwell D, Johansen K. Critical appraisal of the angiographic portacaval shunt (TIPS). Am J Surg. 1993;165:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hermie L, Dhondt E, Vanlangenhove P, Hoste E, Geerts A, Defreyne L. Model for end-stage liver disease score and hemodynamic instability as a predictor of poor outcome in early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt treatment for acute variceal hemorrhage. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:1441-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jabbour N, Zajko AB, Orons PD, Irish W, Bartoli F, Marsh WJ, Dodd GD 3rd, Aldreghitti L, Colangelo J, Rakela J, Fung JJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with end-stage liver disease: results in 85 patients. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jalan R, John TG, Redhead DN, Garden OJ, Simpson KJ, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. A comparative study of emergency transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt and esophageal transection in the management of uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1932-1937. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Le Moine O, Devière J, Ghysels M, François E, Rypens F, Van Gansbeke D, Bourgeois N, Adler M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt as a rescue treatment after sclerotherapy failure in variceal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994;207:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Maimone S, Saffioti F, Filomia R, Alibrandi A, Isgrò G, Calvaruso V, Xirouchakis E, Guerrini GP, Burroughs AK, Tsochatzis E, Patch D. Predictors of Re-bleeding and Mortality Among Patients with Refractory Variceal Bleeding Undergoing Salvage Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS). Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1335-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | McCormick PA, Dick R, Panagou EB, Chin JK, Greenslade L, McIntyre N, Burroughs AK. Emergency transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic stent shunting as salvage treatment for uncontrolled variceal bleeding. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1324-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Patch D, Nikolopoulou V, McCormick A, Dick R, Armonis A, Wannamethee G, Burroughs A. Factors related to early mortality after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for failed endoscopic therapy in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 1998;28:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rubin RA, Haskal ZJ, O'Brien CB, Cope C, Brass CA. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting: decreased survival for patients with high APACHE II scores. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:556-563. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, Tisnado J, Cole PE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for patients with active variceal hemorrhage unresponsive to sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:138-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tyburski JG, Noorily MJ, Wilson RF. Prognostic factors with the use of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for bleeding varices. Arch Surg. 1997;132:626-30; discussion 630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tzeng WS, Wu RH, Lin CY, Chen JJ, Sheu MJ, Koay LB, Lee C. Prediction of mortality after emergent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement: use of APACHE II, Child-Pugh and MELD scores in Asian patients with refractory variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:481-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zhu Y, Wang X, Xi X, Li X, Luo X, Yang L. Emergency Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt: an Effective and Safe Treatment for Uncontrolled Variceal Bleeding. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:2193-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Myers RP, Tandon P, Ney M, Meeberg G, Faris P, Shaheen AA, Aspinall AI, Burak KW. Validation of the five-variable Model for End-stage Liver Disease (5vMELD) for prediction of mortality on the liver transplant waiting list. Liver Int. 2014;34:1176-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kim WR, Mannalithara A, Heimbach JK, Kamath PS, Asrani SK, Biggins SW, Wood NL, Gentry SE, Kwong AJ. MELD 3.0: The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Updated for the Modern Era. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1887-1895.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhou C, Hou C, Cheng D, Tang W, Lv W. Predictive accuracy comparison of MELD and Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores for survival in patients underwent TIPS placement: a systematic meta-analytic review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13464-13472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zhang F, Zhuge Y, Zou X, Zhang M, Peng C, Li Z, Wang T. Different scoring systems in predicting survival in Chinese patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gaba RC, Couture PM, Bui JT, Knuttinen MG, Walzer NM, Kallwitz ER, Berkes JL, Cotler SJ. Prognostic capability of different liver disease scoring systems for prediction of early mortality after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:411-420, 420.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Schepke M, Roth F, Fimmers R, Brensing KA, Sudhop T, Schild HH, Sauerbruch T. Comparison of MELD, Child-Pugh, and Emory model for the prediction of survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1167-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Walter A, Rudler M, Olivas P, Moga L, Trépo E, Robic MA, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Baiges A, Sutter O, Bouzbib C, Peron JM, Le Pennec V, Ganne-Carrié N, Garcia-Pagán JC, Mallet M, Larrue H, Dao T, Thabut D, Hernández-Gea V, Nault JC, Bureau C, Allaire M; Salvage TIPS Group. Combination of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and Lactate Predicts Death in Patients Treated With Salvage Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for Refractory Variceal Bleeding. Hepatology. 2021;74:2085-2101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Africa

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aseni P, Italy S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH