Published online Dec 15, 2010. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v1.i5.171

Revised: November 25, 2010

Accepted: December 2, 2010

Published online: December 15, 2010

Lymphangiomas are rare benign cystic tumors of the lymphatic system. Retroperitoneal lymphangiomas account for 1% of all lymphangiomas, and approximately 186 cases have been reported. They may clinically present as a palpable abdominal mass and can cause diagnostic dilemmas with other retroperitoneal cystic tumors, including those arising from the liver, kidney and pancreas. This report describes the rare case of a cystic retroperitoneal lymphangioma in a 54-year-old male patient. The lymphangioma had progressed to the point of inducing clinical symptoms of abdominal distention, abdominal pain, anorexia, fever, nausea and diarrhea. Radiological imaging revealed a large multiloculated cystic abdominal mass with enhancing septations involving the upper retroperitoneum and extending into the pelvis. Surgical removal of the cyst was accomplished without incident. A benign cystic retroperitoneal lymphangioma was diagnosed on histology and confirmed with immunohistochemical stains.

- Citation: Bhavsar T, Saeed-Vafa D, Harbison S, Inniss S. Retroperitoneal cystic lymphangioma in an adult: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2010; 1(5): 171-176

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v1/i5/171.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v1.i5.171

Lymphangiomas are rare cystic tumors of the lymphatic system. These are benign, slow-growing lesions characterized by proliferating lymphatic vessels[1]. They frequently affect the neck (75%) and the axilla (20%)[2]. Intra-abdominal lymphangiomas (fewer than 5%) have been reported in the mesentery, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, liver and pancreas[3].

Retroperitoneal lymphangiomas account for nearly 1% of all lymphangiomas[4], and are uncommon incidental findings usually at surgery, autopsy or lymphography[5,6]. These may be capillary, cystic or cavernous, with a uniseptate or multiseptate appearance. Although retroperitoneal lymphangiomas may sometimes be asymptomatic[7], they usually present as a palpable abdominal mass, and are easily confused with other retroperitoneal cystic tumors including those arising from the liver, kidney and pancreas. They may become symptomatic if they become large enough to impose on surrounding structures, as was the case in this patient. Retroperitoneal lymphangiomas manifest with clinical symptoms of abdominal pain, fever, fatigue, weight loss, and hematuria, due to their size, and occasionally might be complicated by intracystic hemorrhage, cyst rupture, volvolus or infection[5,6]. Differentiating cystic lymphangiomas from other cystic growths by imaging studies alone is often inconclusive[8], and surgery is most frequently required for definitive diagnosis, and to ameliorate the symptoms. An interesting and rare case of a retroperitoneal cystic lymphangioma in a 54-year-old male patient is described here.

A 54-year-old African-American man presented to the emergency room with abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and nausea for the past week. He had associated anorexia, fever, nausea, diarrhea and intolerance of fluids and food. There was no blood in stools, dysuria, shortness of breath or vomiting. The abdominal pain was diffuse, 10/10 on a pain scale, constant, crampy, and nothing alleviated the pain. The abdominal distention was moderate and no mass was palpated. The bowel sounds were diminished in all quadrants. McBurney’s point was non-tender. His past medical history was relevant for pancreatitis. Differential diagnoses, including bowel obstruction, diverticulitis, hepatitis, non-specific abdominal pain, and non-specific colitis were considered. He was a cigarette smoker, and admitted use of marijuana and cocaine in the past 5 years. On the day of admission, the patient was administered enoxaparin to prevent deep vein thrombosis, oxycodone, acetaminophen, and codeine for pain and ondansetron for nausea and vomiting. Laboratory results showed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 22.7 k/mm3 with 90% segmented cells, albumin of 2.5 gm/dL, and aspartate amino transferease of 14 U/L. Urinalysis revealed urobilinogen of 8 EU/dL, protein 100 mg/dL, pH 6.0, 4-10 red blood cells/high power field and 4-10 white blood cells/high power field.

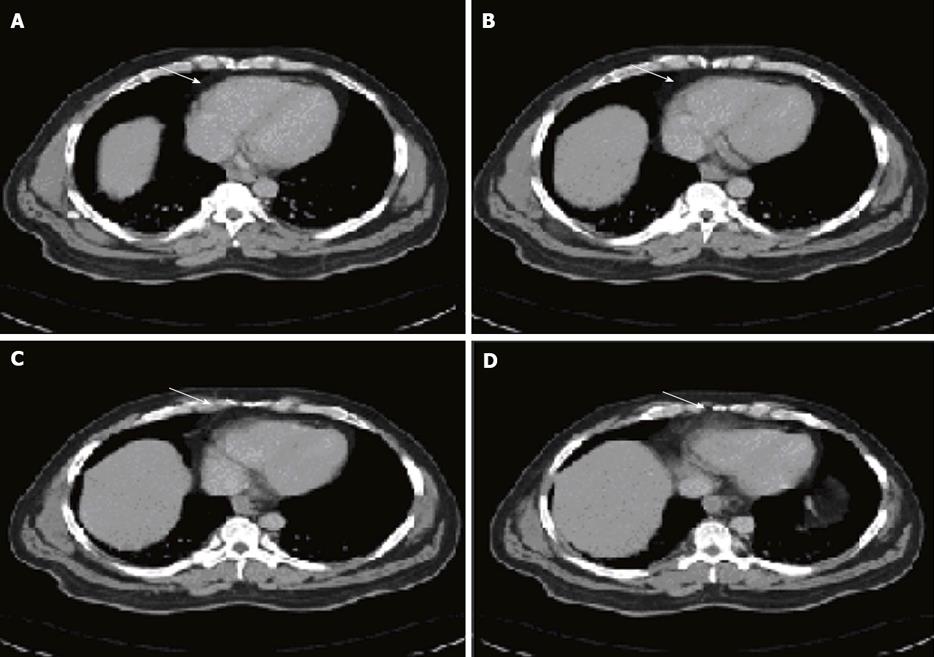

A computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1) showed a large 14.4 cm × 14.6 cm × 9.2 cm multilocular cystic mass with enhancing septations, along with small bowel dilation. The attenuation coefficient of the mass was in the +10 to 15 HU range. The posterior-superior border of the mass was in contact with the third and fourth duodenal segments, while its inferior margin extended into the pelvis, compressing the adjacent bowel loops and causing dilation of the small bowel. The mass was well-circumscribed in its entirety, and there was no evidence of an invasive component. There was no associated ascites. Due to complexity of the cyst with enhancing septations and multiple punctuate calcifications, further evaluation using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and clinical correlation was advised before considering any invasive procedure or biopsy to exclude malignancy.

An MRI scan showed a multiloculated T2 hyperintense lesion measuring 15 cm × 14 cm, with irregular internal septations centered in the left mid abdominal mesentery splaying the bowel loops that was thought be a cystic lymphangioma, mesenteric cyst or cystic mesothelioma. There was no evidence of small bowel obstruction or large bowel obstruction.

Two days post admission, with a preoperative diagnosis of retroperitoneal/mesenteric cyst, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy and excision of the mesenteric cyst. Upon laparotomy, a large, approximately 15 cm retroperitoneal cyst within the mesentery of the small intestine was found. The small bowel and the sigmoid colon were not involved, but were adherent to cyst. The mesentery of the sigmoid colon was not involved. There was a plane of dissection between the sigmoid colon and the cyst that was divided utilizing a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. The small bowel loops that were adherent to the cyst in the lower abdomen were also mobilized in a similar fashion. The cyst was defined and was unroofed. It was filled with approximately 500 cc of cloudy thin pre-operative diagnostic imaging fluid that was aspirated and sent for culture and sensitivity. The cyst was then excised in its entirety by opening the mesentery of the small intestine along the left side. Care was taken to avoid the superior mesenteric vein that was easily identified and lay right next to the cyst itself. The portion of the wall of the cyst was sent for frozen section examination that was diagnosed as a mesenteric cyst with fibrous tissue showing marked acute inflammation, necrosis and few ecstatic blood vessels. With the cyst completely removed and handed off for histopathologic examination, the retroperitoneum and the mesentery was inspected closely. The bowel was run twice and was found to be healthy and viable and uninvolved with the cyst. The patient tolerated the procedure well and his post-operative course was uneventful. The patient underwent a workup including Gram stain of the cyst fluid and culture of urine, blood and the cyst fluid that did not show any organism or growth.

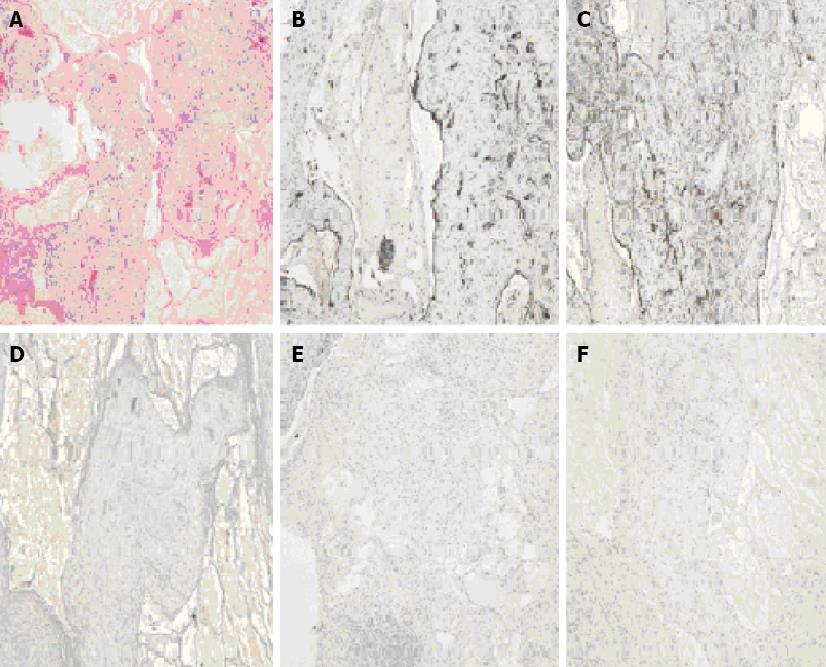

Gross examination of the specimen, designated as “retroperitoneal cyst” showed a mass of red tissue measuring 12.2 cm × 10.7 cm × 1.8 cm and weighing 271 gm. The surface was shiny and smooth, and serial sectioning revealed multiple cysts ranging in 0.2 to 2.6 cm in diameter, filled with cloudy fluid. Histologically, the mass was composed of variable-sized cystic spaces lined by flattened endothelium, that were positive for CD31 (Figure 2B) and D2-40 (Figure 2C) immunostains, consistent with lymphatic vessels. The larger spaces had fascicles of smooth muscle, and nearly all of them were filled with pale pink proteinaceous material (Figure 2A). Small lymphoid aggregates and reactive lymph nodes were present. The stroma showed acute and chronic inflammation, edema and fibrosis. Stains for broad spectrum keratin, EMA (Figure 2F), Ck 5/6, BerEP4 and calretinin (Figure 2D) were negative, ruling out any mesothelial nature of the cyst. The bundles of smooth muscle were negative for HMB-45 (Figure 2E) and CD117, ruling out angiomyolipoma and gastro-intestinal stromal tumor (GIST) respectively. Thus, the diagnosis of a retroperitoneal multilocular-cystic lymphangioma with inflammation was histologically confirmed.

A cystic tumor in the retroperitoneum accounts for widely differing diagnoses, including malignant tumors such as cystic mesothelioma, teratoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, cystic metastases (especially from ovarian or gastric primaries), malignant mesenchymoma, benign tumors such as lymphangioma, cysts of urothelial and foregut origin, microcystic pancreatic adenoma, and other tumors such as retroperitoneal hematoma, abscesses, duplication cysts, ovarian cysts and pancreatic pseudocysts[9].

Lymphangiomas are benign lesions characterized by proliferating lymphatic vessels, and their evaluation as either hamartomas or lymphangiectasis[10] remains a matter of debate. Approximately 50% of lymphangiomas are present at birth, and almost 90% are diagnosed before the age of 2 years. They can occur in any location where lymphatics are normally encountered. The most frequently affected sites are the head and neck (75%), where these are commonly referred to as ‘cystic hygromas’, followed by the axilla (20%)[2]. The remainder (approximately 5%) of the lymphangiomas are intra-abdominal[3] arising from the mesentery, retroperitoneum or greater omentum[11], where they are referred to as ‘omental or mesenteric cysts’. The retroperitoneum is the second-most common location for the abdominal lymphangiomas after mesentery of the small bowel. Various theories have been postulated on the development of lymphangiomas, focusing on a combination of inflammatory, fibrotic and genetic components, and other factors such as mechanical pressure and retention, traumatic factors, degeneration of lymph nodes, and disorders of endothelial lymphatic vascular secretion or permeability. The frequent development of lymphangiomas within areas of primitive lymph sacs suggests these to be malformations arising from sequestrations of lymphatic tissue that fail to communicate normally with the lymphatic system[10], or developmental defects between the 6th-9th wk of embryonic development resulting from abnormal budding of the lymphatic endothelium[12]. These abnormal lymphatic channels would dilate, frequently resulting in the formation of uni- or multi-cystic masses that might subsequently be inflamed or obstructed, leading to additional lymphangiomas. The cystic masses are filled with chylous or serous material and lined with a layer of endothelium[13]. Generally, lymphangiomas are classified into three types; capillary (or simple), cavernous and cystic, depending on the size of the lymphatic spaces[9]. Simple lymphangiomas consist of small, thin-walled, lymphatic channels with considerable connective tissue stroma. Cavernous types are composed of dilated lymphatic channels, whereas cystic lymphangiomas are distinguished by single/multiple cystic masses.

Retroperitoneal lymphangiomas are best described as developmental abnormalities of the lymphatics, and are almost always benign[5]. It is speculated that their development is due to an abnormal connection between the iliac and retroperitoneal lymphatic sacs and the venous system, leading to lymphatic fluid stasis in the sacs. These usually present a diagnostic dilemma, as there are no definitive diagnostic tests and the patient’s history will mostly only exclude traumatic and parasitic cysts[8]. Commonly observed retroperitoneal lymphangiomas are usually of cavernous or cystic types[14], of which most reported cases have been of a cystic nature, as was this case.

The majority of the retroperitoneal lymphangiomas are asymptomatic[7] and are discovered incidentally in later life during radiological procedures for other conditions, or during surgery or autopsy. The most common clinical manifestation is that of a slowly enlarging abdominal mass[5,6], left upper quadrant pain, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, as seen in this case. The mass effect is the potential culprit in causing significant morbidity by obstruction (40%) or dislocation of the adjacent organs. However, retroperitoneal lymphangiomas are infrequently complicated by ascites, bleeding or rupture[5], torsion, volvulus[6] and rarely, ureteric obstruction[6], hematuria or clotting disorders. In our patient, the cystic growth could have been attributed to increasing lymphatic flow and closure of drainage channels, caused by infection or other underlying inflammatory process(es). This cystic expansion caused the clinical manifestation of abdominal distention and pressure on adjacent organs. Abdominal pain and fever, with leukocytosis was probably induced in relation to hemorrhage and/or inflammation of the cyst. Although, based on bacterial and histological investigations, no pathogen was present, the possibility of a viral infection causing the inflammation could not be ruled out.

Pre-operative diagnosis of retroperitoneal lymphangioma, in general, is challenging and rare, prior to laparatomy or laparoscopy[4]. The diagnosis of lymphangioma, based on the radiographic modalities, is generally one of many potential differentials for a multiloculated cystic mass arising retroperitoneally. Our preliminary radiological investigations, however, did include the possibility of a retroperitoneal lymphangioma. Ultrasound (US), CT and MRI have been shown to be complimentary in the diagnosis of retroperitoneal lymphangiomas. US can demonstrate the cystic nature of the lesion appearing with sharp margins, particularly the septations as scattered internal echoes. CT and MRI can demonstrate uni- or multi-locular cysts with septae, an assessment of the relationship of lymphangiomas to neighboring organs[9] and characteristically, fluid of ‘water density’. The ability of MRI to provide images in multiple planes without loss of resolution may demonstrate additional lesions and further delineate the boundaries of the cysts[1]. In this case, abdominal CT/MRI revealed a 15 cm × 14 cm × 9 cm cystic mass in the in the left mid abdominal mesentery. Even though guided biopsy of the lesion is often difficult, and rarely attempted, due to the threat of potential dissemination of malignancy, the likelihood of pre-operative diagnosis is greatest when imaging is combined with biopsy.

The final diagnosis of lymphangioma is achieved by pathological examination of the specimen after surgical or laparoscopic examination, and is based on well-established criteria[14]. These include a well-circumscribed, cystic lesion, with or without endothelial lining, a stroma composed of a meshwork of collagen and fibrous tissue, and a wall containing focal aggregates of lymphoid tissue. Accordingly, histology from the mass in this case showed variable-sized dilated cystic spaces lined by flattened endothelium filled with pale pink proteinaceous material, larger spaces with fascicles of smooth muscles, stroma showing acute and chronic inflammation, edema and fibrosis along with small lymphoid aggregates and reactive lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessel endothelial receptor-1, vascular endothelial growth factor-3, prox-1, and monoclonal antibody D2-40 are the markers for specific endothelial cells of lymphatic tissues that are used in immunochemical studies of lymphangioma. In this case, the endothelium of retroperitoneal cystic mass was stained positive with D2-40 antibody and CD31 immunostain markers. The mass did not stain for broad spectrum keratin, and EMA, Ck 5/6, BerEP4 and calretinin were negative, ruling out any mesothelial nature of the cyst. The bundles of smooth muscle in the mass were negative for HMB-45, thus ruling out angiomyolipoma, and CD117, thus ruling out GIST. The retroperitoneal mass was finally diagnosed as a cystic retroperitoneal lymphangioma, based on the microscopic findings, and confirmed by immunohistochemical stains.

The benign nature of the retroperitoneal lymphangioma warrants a conservative surgical approach such as aspiration; however, in most of such cases, surgery is required, due to the morbidity associated with the tumor size, infrequent spontaneous regression of the cyst[10], and for definitive diagnosis. With cystic retroperitoneal lymphangioma, a simple total excision is usually the preferred treatment to avoid superinfection, progressive growth, rupture or bleeding[11], and the outcome following complete resection is generally good. Rare complications following surgery are peritonitis, bleeding, abscess and torsion[8]. Other forms of surgical management such as cyst-enterostomy or marsupialization have now become obsolete[5]. We performed a simple total excision of the cyst that was deemed an appropriate treatment in our patient. The procedure was tolerated well by the patient, without any clinically significant postoperative course. Recurrence rates for cystic lymphangiomas are low, but may be significant following conservative treatment modalities including aspiration, drainage and sclerosis. There is a possibility of recurrence with incomplete removal[1,5] of the lesion, arising from, or involving an abdominal organ[5]. Dissemination in the retroperitoneum is a very rare, but potentially fatal complication[15].

In conclusion, cystic lymphangioma, a malformation of the lymphatic vessels, should be considered among the many different possible diagnoses of a retroperitoneal cystic lesion. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma is an uncommon lesion in adults, and radiological investigation(s) provides important pre-operative diagnostic information for effective surgical approach and management. These rare tumors have an excellent prognosis, with symptomatic relief and cure achieved with complete surgical excision.

Peer reviewers: Walter Fries, MD, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Therapy, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Via C. Valeria 1, Italy; Fernando Fornari, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Passo Fundo, Rua Teixeira Soares, 817, Centro, Passo Fundo-RS, Postal Code 99010080, Brazil; Hua Yang, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of General Surgery, Xinqiao Hospital, Third Military Medical University Chongqing 400037, China

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Herholdt A E- Editor Liu N

| 1. | Cutillo DP, Swayne LC, Cucco J, Dougan H. CT and MR imaging in cystic abdominal lymphangiomatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:534-536. |

| 2. | de Perrot M, Rostan O, Morel P, Le Coultre C. Abdominal lymphangioma in adults and children. Br J Surg. 1998;85:395-397. |

| 3. | Koenig TR, Loyer EM, Whitman GJ, Raymond AK, Charnsangavej C. Cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas. AJR. 2001;177:1090. |

| 4. | Hauser H, Mischinger HJ, Beham A, Berger A, Cerwenka H, Razmara J, Fruhwirth H, Werkgartner G. Cystic retroperitoneal lymphangiomas in adults. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:322-326. |

| 5. | Roisman I, Manny J, Fields S, Shiloni E. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma. Br J Surg. 1989;76:485-489. |

| 6. | Thomas AM, Leung A, Lynn J. Abdominal cystic lymphangiomatosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 1985;58:467-469. |

| 7. | Chan IYF, Khoo J. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma in an adult. J HK Coll Radiol. 2003;6:94-96. |

| 8. | Yang DM, Jung DH, Kim H, Kang JH, Kim SH, Kim JH, Hwang HY. Retroperitoneal cystic masses: CT, clinical, and pathologic findings and literature review. Radiographics. 2004;24:1353-1365. |

| 9. | Bonhomme A, Broeders A, Oyen RH, Stas M, De Wever I, Baert AL. Cystic lymphangioma of the retroperitoneum. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:156-158. |

| 11. | Fonkalsrud EW. Congenital malformations of the lymphatic system. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1994;3:62-69. |

| 12. | Ho M, Lee CC, Lin TY. Prenatal diagnosis of abdominal lymphangioma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20:205-206. |

| 13. | Cherk M, Nikfarjam M, Christophi C. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:51-54. |

| 14. | Koshy A, Tandon RK, Kapur BM, Rao KV, Joshi K. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma. A case report with review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;69:485-490. |

| 15. | Nishio I, Mandell GL, Ramanathan S, Sumkin JH. Epidural labor analgesia for a patient with disseminated lymphangiomatosis. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1805-1808. |