Published online May 28, 2015. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i5.104

Peer-review started: January 7, 2015

First decision: March 20, 2015

Revised: April 24, 2015

Accepted: April 28, 2015

Article in press: April 30, 2015

Published online: May 28, 2015

Processing time: 146 Days and 16.3 Hours

Two cases of prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PNEC) imaged by computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and literature review are presented. Early enhanced CT, MRI, especially diffusion-weighted image were emphasized, the complementary roles of ultrasound, CT, MRI, clinical and laboratory characteristic’s features in achieving accurate diagnosis were valued in the preoperative diagnosis of PNEC.

Core tip: Prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PNEC) comprised 0.5%-2% of all prostate carcinoma, commonly presents with lymph node, bone, or organ metastases and has a poor prognosis when a definite diagnosis was given in clinic. Our cases and literature suggest it is usually insufficient that the prostate is examined by ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), or prostate specific antigen in serum for the symptomatic and/or with high risk factors crowd. Emphasizing the complementary roles of the malignant signs in diffusion-weighted image, early enhancement in CT or magnetic resonance imaging, self-contradictory clinical appearance and laboratory results can help achieving the accurate diagnosis of PNEC, maybe in early stage.

- Citation: He HQ, Fan SF, Xu Q, Chen ZJ, Li Z. Diagnosis of prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: Two cases report and literature review. World J Radiol 2015; 7(5): 104-109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v7/i5/104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i5.104

According to the World Health Organization 2004 lung tumor classification, neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) was classified as carcinoid tumors, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, and mixed tumors. Prostatic NEC (PNEC) comprised 0.5%-2% of all prostate carcinoma, commonly presents with lymph nodes, bone, or organ metastases and has a poor prognosis when a definite diagnosis was given in clinic[1-4]. Despite some clinical reports in the literature on the management of PNEC, there are limited articles describing its imaging features and diagnosis. To improve the preoperative diagnosis of PNEC, especially in its early stage, we review the related literature, and present two cases of PNEC with imaging, clinical, laboratory and pathologic findings, all showing metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Taizhou Hospital (Linhai, Zhejiang Province, China). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family.

A 78-year-old male patient presented with pollakisuria and an episode of painless gross hematuria for about six-month duration. The patient had no family history of prostate cancer. Rectal examination outlined an irregularly enlarged prostate with an endured right lobe firmer than normal. In laboratory examination, prostate specific antigen (PSA) in serum at admission was within the normal range (0.2 ng/mL). In urine analysis, hemoglobin of 4.3 g/dL and red blood cells were found, while acid and alkaline phosphatase level was within normal range.

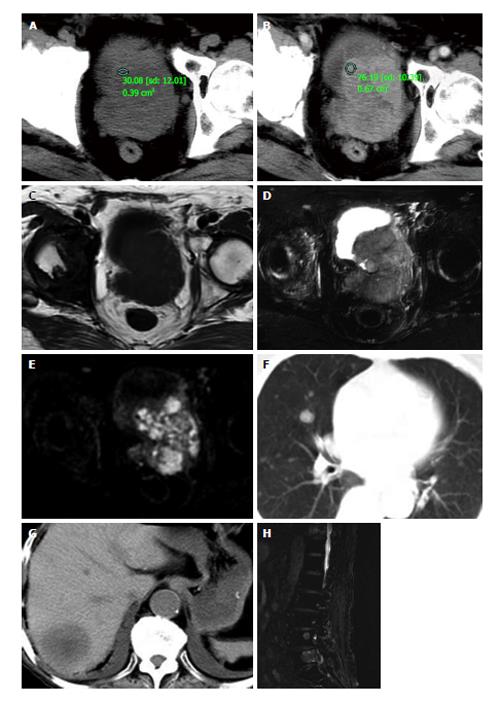

Ultrasonography showed an irregularly enlarged prostate size of 7.1 cm × 7.5 cm × 6.7 cm with inhomogeneous hypoechoic-isoechoic appearance. The diagnosis of ultrasonography was reported as prostatic hyperplasia. Computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1A and B) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1C and E) of pelvic revealed the prostate was approximately 6.5 cm × 7.5 cm × 7.2 cm in size with an irregular border and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvic region. CT images demonstrated the mass was slightly low density with small necrosis in the center region. The solid part enhanced obviously in contrast enhanced CT scanning, while the necrosis part did not. In MR examination, the solid part of the lesion appeared as slightly low signal on T1WI, while higher signal on T2WI and diffusion-weighted image (DWI), its ADC valve was 0.860 ± 0.130 mm2/s. Abdominal CT, chest CT and/or lumbar MRI revealed several metastases in two lungs, liver, and multiple lumbar vertebraes (Figure 1F and H).

Based on the findings of laboratory examination, CT, MRI and literature review, a preferred diagnosis was offered that it was PNEC with pulmonary, hepatic, spine and lymph nodes metastasis.

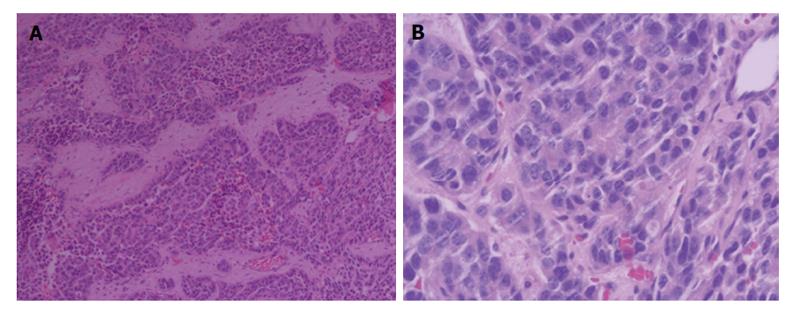

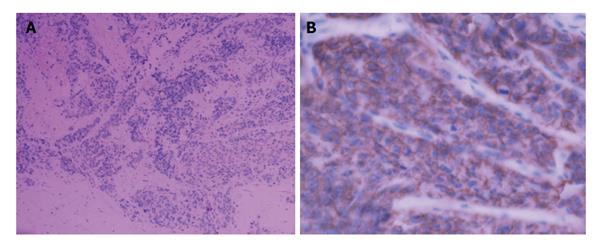

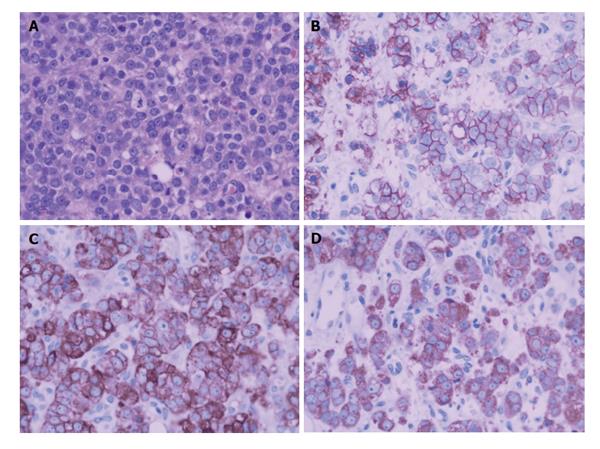

To confirm the diagnosis in pathology, a biopsy of the enlarged prostate was performed. Microscopic finding showed infiltrating nests of small cell in the fibrotic stroma, the tumor cells of which had small hyperchromatic nuclei and scanty cytoplasms, Gleason 3 + 4 (Figure 2). In immunohistochemical staining,the lesion were positive for CgA and CD56, negative for PSA, which was consistent with small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (Figure 3).

Systemic chemotherapy was offered to the patient but he refused it because of personal reasons. To palliate symptoms of the tumor and metastatic lesions, radiotherapy of 300 cGy/d for 10 d was carried out on the prostate, pelvic region and lumbar vertebrae. He died 7 mo after diagnosis.

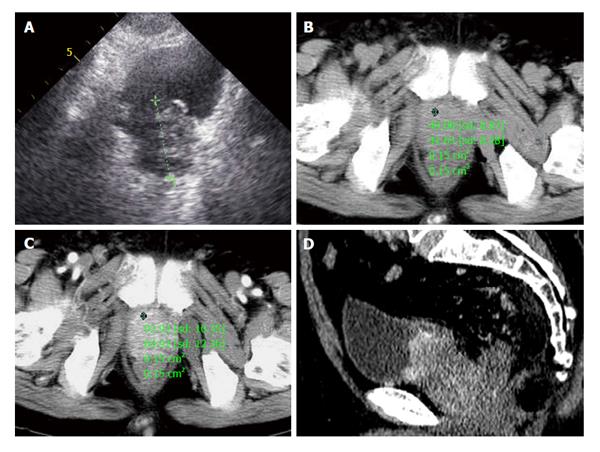

A 72-year-old male patient presented with one month of dysuria. Sonography showed the prostate enlarged to 4.0 cm × 5.1 cm × 4.2 cm with incomplete envelope, irregular shape and heterogeneous echo texture (Figure 4A). The serum level of PSA was within the normal range (0.73 ng/mL). CT scans of pelvic revealed the boundaries of increased prostate were unclear with bladder, seminal vesicle, and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the retroperitoneal region (Figure 4B). In contrast enhanced CT scanning, obvious enhancement parts of enlarged prostate and lymph nodes were showed in arterial phase (Figure 4C and D). Chest and abdominal CT were obtained to check the other organs of the body, and found no evidence of lesions. CT signs suggested a diagnosis of prostatic malignant tumor accompanied by lymphatic metastasis. A preferred diagnosis of PNEC with lymph nodes metastasis was offered.

A biopsy of the prostate mass was adopted to confirm the diagnosis in pathology. Pathologic analysis of the fully sampled prostate and adjacent areas identified small cell carcinoma (Figure 5A, Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7), immunohistochemical studies (Figure 5B and D) showed positive staining with Syn(++), CgA(++), CD56(++),CK(+), AR(+++), and negative with CK20(-), PSA(-).

To remit and relieve symptoms of the tumor and metastatic lymph nodes, radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy were carried out on the prostate and pelvic region. He survived for longer than the first case and died 29 mo after diagnosis.

PNEC, most identical to small cell carcinomas in clinic, is rare with different presentations and mostly diagnosed at the advanced stage by biopsy or surgery and generally believed to have a high metastatic potential and a poor prognosis[3-5]. Preoperative diagnosis, especially at the early stage of PNCE, may be helpful for surgery, adjuvant therapy and improving prognosis though it is difficult separately dependent on clinical, laboratory or imaging presentations.

The clinical features of this disease are similar to those of prostate adenocarcinoma. The most frequent symptoms at presentation include lower urinary tract symptoms and acute urinary retention, but pain and paraneoplastic syndromes may be the first manifestations in rare cases[2,4]. In our cases, the symptoms of the patients mainly include frequent urination, hematuria and dysuria, there were no paraneoplastic syndromes. Neuroendocrine cells of PNEC do not produce PSA, the serum level of PSA of the majority was within the normal range, except a few cases with mixed tumors with PSA slightly increased in serum[6,7]. In our cases, the serum level of PSA all were normal which is infrequent in prostate cancer.

The morphologic features of NEC of the prostate are similar to those of other sites. As for the prostate, the most widely used imaging examination is the pelvic ultrasonography, CT and MRI scan. To our knowledge, there are only several cases of PNEC which imaging signs have been primitively described in literatures by now[7,8], which are not sufficient to characterize the imaging findings of the tumor, but which hint MRI and contrast-enhanced CT examination may be sensitive in showing the abnormal signs. The radiologic findings of our cases were similar to the NEC in other sites. The imaging differences of PNEC to the benign diseases of prostate may include its higher signal in T2WI and DWI, more enhanced in arterial phase, irregular form infiltrated and/or metastasized to other regional, such as lymph nodes, bone or the liver and so on, which all can be seen in other malignant neoplasm of prostate though some signs are infrequency in others.

In summary, there usually isn’t enough characteristic evidence for preoperative diagnosis, especially at early stage of PNCE alone in clinical, laboratory, plain ultrasound (US) or CT imaging presentations. If there are paraneoplastic syndromes though it is rare in clinic and malignant imaging signs, the diagnosis of PNCE can be made[8-10]. If there are malignant imaging signs, but without correspondingly increased PSA in serum and without paraneoplastic syndromes in clinic, PNCE should be considered in the differential diagnosis, which can be confirmed by biopsy, histology and immunohistochemistry[2,4,10]. Our cases and literature suggest PNEC often locate at the central zone of prostate with obviously contrast enhancement, abnormal signal in MR images, especially in DWI. It usually is insufficient that the prostate is examined by US and CT, or PSA in serum within normal range for the symptomatic and/or with high risk factors crowd. For patients with symptom and/or with high risk factors, DWI, early enhancement in CT, MRI should be emphasized, and the complementary roles of the imaging malignant signs, self-contradictory clinical appearance and laboratory results should be emphasized. Which can help achieving accurate diagnosis, maybe in early stage, in the preoperative diagnosis of PNEC. We believe it will test and enrich the imaging characteristics of PNEC to check more cases in future.

The clinical symptoms of the two cases were also dissimilar, one presented with pollakisuria and an episode of painless gross hematuria, and the other presented with dysuria.

Two men with prostatic malignant tumor.

Malignant tumors (prostatic carcinoma, sarcoma, carcinoma sareomatodes and malignant fibrous histiocytoma), benign neoplasms (prostatic hyperplasia, granuloma).

The first patient had hemoglobin of 4.3 g/dL and red blood cells in urine analysis, while the second patient had no remarkable findings for the laboratory tests.

For both cases, computed tomography (CT) scan and ultrasonography showed an irregularly enlarged prostate. The first case also underwent magnetic resonance examination.

For both cases, histological examination showed small cell carcinoma, immunohistochemical studies showed positive for CgA and CD56, negative for prostate specific antigen.

The first case underwent only radiotherapy for 10 d on the prostate, pelvic region and lumbar vertebrae, while radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy were all carried out on the prostate and pelvic region for the second patient.

Very few ultrasound, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PNEC) have been reported in the literature. The diagnostic value of imaging findings remains unclear and the role of treatment in early stage of PNEC is controversial.

PNCE: Prostatic neuroendocrine carcinoma.

This case report presents the clinical and imaging characteristics of PNEC and also discusses the diagnostic value of imaging findings of PNEC. The authors recommend that more attention should be paid to the complementary roles of the malignant signs in diffusion-weighted image, early enhancement in CT or MRI, self-contradictory clinical appearance and laboratory findings.

Concise review of imaging and pathological findings of neuroendocrine prostate cancer.

| 1. | Ather MH, Siddiqui T. The genetics of neuroendocrine prostate cancers: a review of current and emerging candidates. Appl Clin Genet. 2012;5:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang W, Epstein JI. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 95 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Walenkamp AM, Sonke GS, Sleijfer DT. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Addeo A, Rinaldi C, Panades M. A case of small cell carcinoma of the prostate and review of the literature. Tumori. 2012;98:76e-78e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ketata S, Ketata H, Fakhfakh H, Sahnoun A, Bahloul A, Boudawara T, Mhiri MN. Pure primary neuroendocrine tumor of the prostate: a rare entity. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5:82-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Uemura KI, Nakagawa G, Chikui K, Moriya F, Nakiri M, Hayashi T, Suekane S, Matsuoka K. A useful treatment for patients with advanced mixed-type small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:793-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giordano S, Tolonen T, Tolonen T, Hirsimäki S, Kataja V. A pure primary low-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid tumor) of the prostate. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:683-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Albisinni S, De Nunzio C, Tubaro A. Pure small cell carcinoma of the prostate: A rare tumor. Indian J Urol. 2012;28:89-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alwani RA, Neggers SJ, van der Klift M, Baggen MG, van Leenders GJ, van Aken MO, van der Lely AJ, de Herder WW, Feelders RA. Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic ACTH production by (neuroendocrine) prostate carcinoma. Pituitary. 2009;12:280-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Simon RA, di Sant’Agnese PA, Huang LS, Xu H, Yao JL, Yang Q, Liang S, Liu J, Yu R, Cheng L. CD44 expression is a feature of prostatic small cell carcinoma and distinguishes it from its mimickers. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:252-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Chu JP, Jain S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/