Published online Oct 28, 2015. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i10.357

Peer-review started: April 8, 2015

First decision: May 13, 2015

Revised: June 23, 2015

Accepted: June 30, 2015

Article in press: July 2, 2015

Published online: October 28, 2015

Processing time: 210 Days and 5.9 Hours

Ligament disruptions at the craniovertebral junction are typically associated with atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation during upper cervical spine injuries and require external orthoses or surgical stabilization. Only in few patients isolated ruptures of the alar ligament have been reported. Here we present a further case, in which the diagnosis was initially obscured by a misleading clinical symptomatology but finally established six month following the trauma, demonstrating the value of contrast-enhanced high resolution 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging in identifying this particular lesion.

Core tip: Upper cervical spine injuries are common and bear a relevant medical and socioeconomic impact. While most of such lesions are related to atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation, thus far only few patients with isolated alar ligament ruptures have been reported. This particular trauma is a challenge to both clinicians and radiologists and diagnosis might thus be delayed. Here we present a further case of a young adult and discuss the value of sequential contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in establishing this diagnosis at a late stage and in the follow-up of a subsequently prolonged recovery.

- Citation: Kaufmann RA, Marzi I, Vogl TJ. Delayed diagnosis of isolated alar ligament rupture: A case report. World J Radiol 2015; 7(10): 357-360

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v7/i10/357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i10.357

Upper cervical spine injuries are common and mainly caused by car and sport accidents or falls. They frequently are associated with long-term impairment or work disability of involved individuals and bear a relevant medical and socioeconomic impact[1-4]. Particularly, cases with hyperextension and rotation of the neck may eventually result in ligament ruptures, though this incident is not necessarily correlated with the intensity of the trauma[5,6]. While most of such lesions are related to atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation, thus far only few patients with isolated alar ligament ruptures have been reported[7]. Probably these cases are underdiagnosed, since they might be missed on initial presentation and only be identified in the context with persistent cervical instability. Here we present a case of a young adult and discuss the value of sequential contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in establishing this diagnosis at a late stage and in the follow-up of a subsequently prolonged recovery.

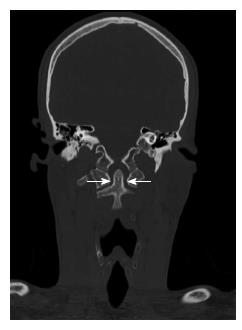

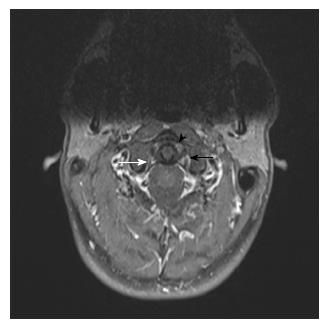

A 25-year-old man was diagnosed with rupture of the tympanic membrane of the left ear following a blunt fist hit trauma to the left side of his head associated with a short period of retro- and ante-grade amnesia, hearing impairment and tinnitus. While topical membrane patching led to complete healing with reestablishment of hearing, ipsilateral tinnitus remained and was accompanied by intermittent occipital pain. Moreover, during the following weeks and after repetitive sport exercises including headstands the patient developed further symptoms such as projecting aching in both shoulders, neck stiffness, dysphagia, fasciculation predominantly in the left arm, paraesthesia along the thoracic spine, neuralgiform pain attacks in the chest, few episodes of unexplainable shivering without fever and some other vague symptoms. On repetitive neurological examination there was no evidence of any objective deficits apart from an impaired neck rotation to the left side. A plain MRI excluded cervical disc herniation and except a straightening of the cervical spine reported no otherwise pathology. Mobilization and physiotherapy was advised leading to further exacerbation of symptoms. After a chiropractic manoeuvre attempted by an orthopaedic surgeon the tinnitus was felt louder and of higher frequency. An additional osteopathic treatment with repetitive sessions of rotational overstretching of the cervical spine above the tolerable pain threshold further aggravated the symptomatology. Recalling the earlier blunt injury a traumatologist was finally consulted 6 mo after the initial event who disclosed a pathologic cervical hypermobility on rotating the neck to the right site, which was considered highly suspicious of a ligament lesion within the atlantoaxial joint. At this time a computed tomography (CT) scan ruled out a fracture or atlanto-occipital dislocation but revealed a slight shift of the dens towards the right lateral mass of C-1 (Figure 1). An MRI (Magnetom Prisma 3T, Siemens Healthcare) confirmed loss of lordosis on sagittal plane while the contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted sequences disclosed increased signal intensity within the apex of the dens as well as within the widened left lateral dens-atlas space indicative of edema. Moreover, the dark signal of the left alar ligament proved to be interrupted (Figure 2), whereas the tectorial membrane and transverse ligament as well as the spinal cord appeared intact. Taken together, the findings were suggestive of an isolated rupture of the left alar ligament.

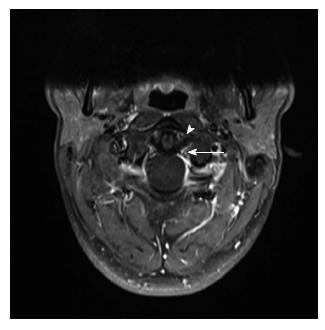

Subsequently, the cervical spine was immobilized by means of a Philadelphia collar, leading to a partial relief of the symptoms. Follow-up MRI of the cervical spine 3 mo later still showed signal hyperintensity within the alar ligament and the apex of the dens while its deviation apparently almost had resolved. After allowing for less cervical immobilization using a soft collar the patient’s complaint worsened again and a subsequent MRI two months later still confirmed hyperintense signalling of the involved ligament and dens. The Philadelphia collar was reintroduced and following another 3 mo of immobilization a 3rd MRI sequence showed marked improvement (Figure 3). The patient gained a progressively increasing range of neck motion in each plane and was nearly free of any discomfort except a feeling of cervical tension increasing during the day, sporadic periods of head and chest pain and persistent tinnitus of varying intensity.

Isolated unilateral alar ligament rupture is a diagnosis made by excluding associated dislocation, fracture, or disruption of other ligamentous structures in the craniovertebral junction. Only recently Wong et al[7] emphasized the special anatomical and pathophysiological aspects of this particular trauma and the value of CT and MRI to confirm the diagnosis discussing a 9 years old girl and reviewing 6 additional cases from the literature aged between 5 and 21 years, all of which fully recovered after conservative immobilization therapy within 1 year[7].

While cervical X-ray, CT and MRI (T2-weighted and STIR sequences) of spinal ligamentous and soft tissue trauma are normally initiated in an acute setting[8,9], in some cases appropriate imaging of cervical injuries might be missed initially or performed with delay for a variety of reasons[10-12]. Also in our patient an appropriate diagnostic work-up had finally been delayed for several months, since the initial trauma and symptoms were apparently considered inadequate for further imaging analysis. MRI studies of patients with suspected occult cervical injury are well established to detect ligamentous injuries including the alar ligament[13-15]. However, in the case presented here an earlier non contrast-enhanced MRI was performed in a private practice to check exclusively for cervical disc herniation as a potential cause of the unexplained symptoms and a ligament lesion was not suspected at that time. Only after subjective symptoms worsened and were possibly linked to the earlier trauma the potential lesion became evident after simply demonstrating contralateral hypermobility on physical testing.

For an optimal detection of ligamentous lesions, the strength of the MRI has been suggested to be at least 1.5 Tesla, which corresponds to half of the magnetic field strength used in our case for an optimal resolution. A slice thickness of 2 mm is reported to give excellent spatial resolution of the injured alar ligaments[16]. Since T1-weighted images provide poor contrast resolution and thus less ability to differentiate small variations in signalling we in addition used a Gadolinium contrast enhanced imaging technique. We evaluated the unenhanced and enhanced images in comparison and could better stage the amount of ligamentous injury and an oedema of surrounding tissues.

On our final MRI after initiating the 12 mo immobilization therapy no relevant ligament or dens pathology could be documented. However, our patient still complaint of tinnitus and recurrent episodes of neck pressure, headaches and chest pain. Persisting symptoms following cervical injuries are well documented in the literature and seem likely if a healing after two years has not been achieved and more frequent in older individuals[17,18]. Whether in our patient an instant diagnosis followed by immediate external orthoses or surgical therapy according to recent recommendations would have led to an entire and earlier relief of symptoms remains however hypothetical. In conclusion, we emphasize the value of contrast high resolution 3 Tesla MRI for the detection of ligamentous injuries at the craniovertebral junction[19].

Patient presented with neck stiffness, dysphagia, fasciculation, paraesthesia and neuralgiform pain attacks.

Findings were suspicious of cervical ligament lesion.

Spectrum of atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation.

3T Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fat-saturated gradient echo sequence (contrast-enhanced T1w fat-suppressed MRI sequence) showed a contrast enhancement in the periligamentous venous plexus with an asymmetry of the joint spaces.

Alar ligament rupture.

Twelve months immobilization therapy.

Wong ST, Ernest K, Fan G, Zovickian J, Pang D. Isolated unilateral rupture of the alar ligament. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2014; 13: 541-547.

This particular trauma is a challenge and diagnosis might be delayed. We emphasize the value of contrast high resolution 3 Tesla MRI for the detection of ligamentous injuries at the craniovertebral junction.

The authors present a case report on a delayed diagnosis of isolated alar ligament rupture and the added value of 3 Tesla MRI for the proper assessment. The paper is well written. Appropiate iconography. The purpose is well defined and it transmits properly the message becoming of potential interest for the readers.

| 1. | Buitenhuis J, de Jong PJ, Jaspers JP, Groothoff JW. Work disability after whiplash: a prospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:262-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Walton DM, Macdermid JC, Giorgianni AA, Mascarenhas JC, West SC, Zammit CA. Risk factors for persistent problems following acute whiplash injury: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:31-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McKinney MB. [Treatment of dislocations of the cervical vertebrae in so-called “whiplash injuries”]. Orthopade. 1994;23:287-290. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Grifka J, Hedtmann A, Pape HG, Witte H, Bär HF. [Biomechanics of injury of the cervical spine]. Orthopade. 1998;27:802-812. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Saternus KS, Thrun C. [Traumatology of the alar ligaments]. Aktuelle Traumatol. 1987;17:214-218. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pfirrmann CW, Binkert CA, Zanetti M, Boos N, Hodler J. Functional MR imaging of the craniocervical junction. Correlation with alar ligaments and occipito-atlantoaxial joint morphology: a study in 50 asymptomatic subjects. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000;130:645-651. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wong ST, Ernest K, Fan G, Zovickian J, Pang D. Isolated unilateral rupture of the alar ligament. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dundamadappa SK, Cauley KA. MR imaging of acute cervical spinal ligamentous and soft tissue trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Landi A, Pietrantonio A, Marotta N, Mancarella C, Delfini R. Atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation (AARD) in pediatric age: MRI study on conservative treatment with Philadelphia collar--experience of nine consecutive cases. Eur Spine J. 2012;21 Suppl 1:S94-S99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gerrelts BD, Petersen EU, Mabry J, Petersen SR. Delayed diagnosis of cervical spine injuries. J Trauma. 1991;31:1622-1626. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Platzer P, Hauswirth N, Jaindl M, Chatwani S, Vecsei V, Gaebler C. Delayed or missed diagnosis of cervical spine injuries. J Trauma. 2006;61:150-155. [PubMed] |

| 12. | O’Shaughnessy J, Grenier JM, Stern PJ. A delayed diagnosis of bilateral facet dislocation of the cervical spine: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58:45-51. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Geck MJ, Yoo S, Wang JC. Assessment of cervical ligamentous injury in trauma patients using MRI. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:371-377. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ackland HM, Cameron PA, Varma DK, Fitt GJ, Cooper DJ, Wolfe R, Malham GM, Rosenfeld JV, Williamson OD, Liew SM. Cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging in alert, neurologically intact trauma patients with persistent midline tenderness and negative computed tomography results. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:521-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wilmink JT, Patijn J. MR imaging of alar ligament in whiplash-associated disorders: an observer study. Neuroradiology. 2001;43:859-863. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Krakenes J, Kaale BR, Moen G, Nordli H, Gilhus NE, Rorvik J. MRI assessment of the alar ligaments in the late stage of whiplash injury--a study of structural abnormalities and observer agreement. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:617-624. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Long-term prognosis of soft-tissue injuries of the neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:901-903. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bunketorp L, Nordholm L, Carlsson J. A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:227-234. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Joaquim AF, Ghizoni E, Tedeschi H, Lawrence B, Brodke DS, Vaccaro AR, Patel AA. Upper cervical injuries - a rational approach to guide surgical management. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37:139-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Akcar N, Gumustas OG, Storto G, Sureka B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK