Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.928

Revised: September 1, 2014

Accepted: November 7, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 164 Days and 8.4 Hours

A young Somali immigrant presents with a two-year history of a large, firm, painful right anterolateral chest wall sternal mass. The patient denied any history of trauma or infection at the site and did not have a fever, erythematous lesion at the site, clubbing, or lymphadenopathy. A lateral chest radiograph demonstrated a low density mass isolated to the subcutaneous soft tissue overlying the sternum, ribs and clavicle. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast demonstrated a cystic lesion in the right anterolateral chest wall deep to the pectoralis muscle. Enhanced CT of the chest demonstrated sclerosis and destruction of the rib and costochondral joint and manubrio-sternal joint narrowing. Ultrasound-guided biopsy and aspiration returned 500 cc of purulent, cloudy yellow, foul-smelling fluid. Acid-fact bacilli stain and the nucleic acid amplification test identified and confirmed Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A diagnosis of tuberculous osteomyelitis/septic arthritis was made and antibiotic coverage for tuberculosis was initiated.

Core tip: Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the immigrant population and other high-risk groups, and must be considered a causative agent of fevers in the retuning traveller. TB osteomyelitis/arthritis is much more indolent clinically and radiologically than bacterial osteomyelitis/arthritis, and therefore, a high index of suspicion must be maintained in individuals immigrating and who have compromised immune function.

- Citation: Patel P, Gray RR. Tuberculous osteomyelitis/arthritis of the first costo-clavicular joint and sternum. World J Radiol 2014; 6(12): 928-931

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i12/928.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.928

A 23 years old Somali man with a history of cognitive delay secondary to brain trauma presented with a two-year history of a large, firm, painful right anterolateral chest wall sternal mass measuring 6 cm × 13 cm × 12 cm.

He denied any history of trauma or infection at the site. No fever, erythematous lesion, clubbing, or lymphadenopathy was noted but the patient did have weight loss. Laboratory workup noted mild microcytic anemia. A series of imaging studies were performed to elucidate the cause of the anterolateral chest mass.

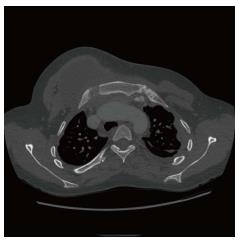

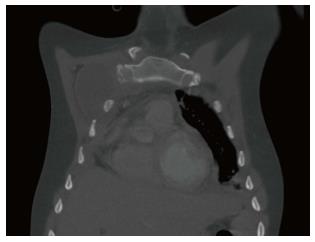

A lateral chest radiograph (Figure 1) demonstrated a low density mass isolated to the subcutaneous soft tissues overlying the sternum, ribs and clavicle. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast (Figures 2 and 3) showed a cystic lesion in the right anterolateral chest wall, deep to the pectoralis muscle. Enhanced CT of the chest (Figure 3) demonstrated sclerosis of the distal portion of the right first rib along with bone destruction at the costochondral joint, medial cortex of the manubrium, and manubrio-sternal joint space narrowing.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy and aspiration was performed, which returned approximately 500 cc of purulent, cloudy yellow, foul-smelling fluid. Microbiological assessment revealed scant acid-fast bacilli and a subsequent nucleic acid amplification test confirmed Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A diagnosis of tuberculous osteomyelitis/septic arthritis was made and antibiotic coverage for tuberculosis initiated.

Risk factors for tuberculosis were all negative and there was no history of diabetes or alcohol abuse.

Three weeks into anti-tuberculosis therapy, the patient unexpectedly experienced a five-minute long tonic-clonic seizure. Head CT revealed intraparenchymal tuberculoma with leptomeningeal findings, in keeping with neurological TB. TB therapy was intensified and dexamethasone was included to treat the brain lesions. Enhanced chest CT illustrated that the sternal mass had decreased in size and that the osteolytic process had been halted. The patient was discharged and advised to seek medical attention should constitutional symptoms develop or the size of the mass increase.

Approximately 25 cases of TB sternal osteomyelitis have been reported in all peer-reviewed journals to date. Bone and joint TB infections account for approximately 6%-10% of all extra-pulmonary TB cases and about 1% of all TB cases in the United States. More specifically, sternal TB osteomyelitis accounts for less than 0.3% of all osteomyelitis cases and 1% of all skeletal TB. Despite a reduction in the global prevalence of TB, 37% of smear-positive TB cases are not being treated and 90% of multidrug resistance TB are not adequately diagnosed and treated[1,2].

Approximately 95% of all TB cases are reported in the Middle East, Africa, Southern Asia, East Asia, and Latin America. African and East Asian immigrants have the greatest risk of bone and joint tuberculosis[3,4]. Sternal TB osteomyelitis tends to predominate in males rather than females, and the mean age of diagnosis is 36[1].

The most common pyogenic causes of osteomyelitis are Staphylococcos aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whilst Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an extremely rare causative pathogen in healthy individuals in the world[5-7].

Risk factors for tuberculous sternal osteomyelitis include: being in or from an endemic area, poor access to health care, immune suppression, nosocomial exposure to TB, drug resistant strains, HIV infection, sternotomy, IV drug use, subclavian vein catheterization, BCG vaccination, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, and advanced age[1,5,8].

Dissemination of primary tuberculosis to bone or other sites occurs in untreated TB or in high-risk patients[4,5]. The most common presenting clinical feature of tuberculous sternal osteomyelitis is an insidious development of pain and swelling over many months, usually without constitutional symptoms (malaise, fever, chills, night sweats, and weight loss)[4]. Erythema, warmth, tenderness, local lymphadenopathy, bone deformity/fracture, and abscess may be seen, but are less common. This is in stark contrast to pyogenic osteomyelitis, which causes a sudden onset of pain and swelling, in addition to constitutional symptomatology[1,4,5]. Complications of prolonged infection include: fistula formation, spontaneous sternal fracture, blood vessel erosion, and tracheal compression[6].

High clinical suspicion in high-risk patients is key for diagnosing TB. The most common laboratory findings are an elevated ESR and white blood cell count[1]. Biopsy samples should be taken from deep structures such as bone, abscess fluid, or synovial fluid and should be sent for histological granulomatous assessment and acid-fast bacilli staining[6].

Radiographic plain films demonstrate a constellation of findings in keeping with bone and joint destruction. Bone loss is the most common finding, and to a variable degree, sclerosis, osteolytic lesions, and periosteal reactions are also seen; in a case-series of sternal TB, 73% of the cases showed a normal radiograph. CT is best utilized for assessing soft tissue and the extent of mediastinal or pulmonary involvement; it is suboptimal for bone analysis[1,5,6]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging use has increased in the last 11 years because it helps to simultaneously assess bone and soft tissue to a high degree, can differentiate between osteomyelitis and soft tissue inflammation, and can assess changes to medullary bone[5,6]. Nuclear Medicine technetium triphasic scintigraphy is a highly sensitive and specific imaging study for the diagnoses of osteomyelitis because it detects bone turnover rate; however, it does not reveal the causative agent and its anatomical precision is suboptimal[1,6].

Treatment of sternal tuberculous osteomyelitis includes prompt initiation of multidrug consisting of rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2-7 mo, followed by maintenance therapy with isoniazid and rifampin[1,8,9]. To prevent recurrence or formation of a draining sinus it is recommended that early surgical debridement be utilized to prevent the build up of necrotic material[1,10-12]. Debridement, which may include sternectomy, must still be followed with medical treatment and the patient must be aware of the complications associated with sternectomy, which include: difficulty with skin closure, pectus excavatum, and secondary mediastinal spread[1,10,12].

Immigrants from areas endemic to TB have a high risk of reactivation of a latent infection. Physicians can expect to see more mycobacterial bone and joint disease in North America as a result of increased travel, immigration, and use of immune suppressant medications. Including TB in the differential diagnosis in patients coming from abroad is critical in the diagnosis and prevention of disease[9].

TB infections may cause severe damage, which can be mitigated if detected and treated early. Recognizing that tuberculosis affects up to one third of the world’s population should compel physicians to consider a diagnosis of TB in patients with aforementioned risk factors.

A diagnosis of osteomyelitis/arthritis secondary to Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the sternum in a 23 years old Somali immigrant.

The patient presented with a 2 years history of a chronically enlarging, painful, anterior chest wall mass.

Traumatic chest wall injury, lung mass/abscess, skin and soft tissue mass.

WBC 9.6 × 109/L (2.0-8.0 × 109/L); neutrophils 0.6 × 109/L (0.7-3.5 × 109/L). The remaining blood count, metabolic, and liver panel lab parameters were all within normal limits.

A lateral chest radiograph demonstrated a low-density mass overlying the sternum, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a cytic lesion deep to the pectoralis muscle, and enhanced CT demonstrated sclerosis and erosion of the manubrio-sternal region.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex ISOLATED on solid media after 24 d incubation period.

Ultrasound-guided aspiration, surgical debridement, and anti-tubercular agents (rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) were initiated.

The patient suffered from cognitive delay secondary to a traumatic brain injury in infancy but was otherwise healthy; immigration from Somalia was the only risk factor he had for tuberculosis.

A high index of suspicion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection must be maintained in the immigrant population and travellers returning from endemic TB areas.

This is a nice article, which reported an unusual case that may lead to further research.

| 1. | Vasa M, Ohikhuare C, Brickner L. Primary sternal tuberculosis osteomyelitis: A case report and discussion. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:e181-e184. [PubMed] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control – epidemiology, strategy, financing: WHO Report 2009. Available from: http: //www.who.int/tb/publication/global_report/2009/en/index.html. |

| 3. | Hadadi A, Rasoulinejad M, Khashayar P, Mosavi M, Maghighi Morad M. Osteoarticular tuberculosis in Tehran, Iran: a 2-year study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1270-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gardam M, Lim S. Mycobacterial osteomyelitis and arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:819-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Atasoy C, Oztekin PS, Ozdemir N, Sak SD, Erden I, Akyar S. CT and MRI in tuberculous sternal osteomyelitis: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2002;26:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saifudheen K, Anoop TM, Mini PN, Ramachandran M, Jabbar PK, Jayaprakash R. Primary tubercular osteomyelitis of the sternum. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e164-e166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stewart KJ, Ahmed OA, Laing RB, Holmes JD. Mycobacterium tuberculosis presenting as sternal osteomyelitis. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45:135-137. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Vohra R, Kang HS, Dogra S, Saggar RR, Sharma R. Tuberculous osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:562-566. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dhillon MS, Gupta RK, Bahadur R, Nagi ON. Tuberculosis of the sternoclavicular joints. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:514-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ford SJ, Rathinam S, King JE, Vaughan R. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of the sternum: successful management with debridement and vacuum assisted closure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:645-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hsu HS, Wang LS, Wu YC, Fahn HJ, Huang MH. Management of primary chest wall tuberculosis. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;29:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | O'Brien DP, Athan E, Hughes A, Johnson PD. Successful treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans osteomyelitis with minor surgical debridement and prolonged rifampicin and ciprofloxacin therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Parwati I, Storto G, Wiwanitkit V S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ