Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.913

Revised: October 24, 2014

Accepted: October 31, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 210 Days and 7.6 Hours

AIM: To assess the frequency of visualization, position and diameter of normal appendix on 128-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) in adult population.

METHODS: Retrospective cross sectional study conducted at Radiology Department, Dallah Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from March 2013 to October 2013. Non-enhanced computed tomography scans of abdomen and pelvis of 98 patients presenting with hematuria (not associated with abdominal pain, fever or colonic disease) were reviewed by two radiologists, blinded to patient history. The study group included 55 females and 43 males with overall mean age of 54.7 years (range 21 to 94 years). The coronal reformatted images were reviewed in addition to the axial images. The frequency of visualization of appendix was recorded with assessment of position, diameter and luminal contents.

RESULTS: The appendix was recorded as definitely visualized in 99% of patients and mean outer-to-outer diameter of the appendix was 5.6 ± 1.3 mm (range 3.0-11.0 mm).

CONCLUSION: MDCT with its multiplanar reformation display is extremely useful for visualization of normal appendix. The normal appendix is very variable in its position and diameter. In the absence of other signs, the diagnosis of acute appendix should not be made solely on outer-to-outer appendiceal diameter.

Core tip: With recent advances in computed tomographic technology, there is improvement in quality of imaging with better spatial and contrast resolution, which has resulted in improved diagnosis and management of patients specially with acute appendicitis. In our institute 128-slice multidetector computed tomography installed last year, which improved our confidence of visualization of appendix. We reviewed our set of patients and looked specifically at outer-to-outer diameter of normal appendix which varied between 3 mm to 11 mm, these findings further emphasized that there is substantial variability in cutoff of normal appendiceal diameter which was up to 11 mm in our series. This further potentiated the fact that acute appendicitis can not be established solely on the base of diameter.

- Citation: Yaqoob J, Idris M, Alam MS, Kashif N. Can outer-to-outer diameter be used alone in diagnosing appendicitis on 128-slice MDCT? World J Radiol 2014; 6(12): 913-918

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i12/913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.913

With recent advances in computed tomography (CT) expertise, particularly the introduction of multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scans, CT has now become the main imaging modality for assessment of adult patients with probable appendicitis[1]. Imaging of normal appendix is better at CT scan than ultrasound essentially excluding the diagnosis of acute appendicitis[2,3]. Various CT techniques have been applied for appropriate detection of abnormal appendix including unenhanced and enhanced CT scans with intravenous, both oral and intravenous and sometimes, oral, intravenous and intrarectal contrast material. Reported accuracies of these techniques have varied but generally are comparable[2,3]. Most of the previous studies have been conducted on helical scanners and have mainly focused on abnormal rather than normal appendix. With availability of multidetector technology thinner collimation and faster scanning is possible, improving scanning resolution and enabling reformations in any desired plane, similar spatially to the reformations obtained in the axial plane[4,5]. This also elucidates the gaining acceptance of techniques without intravenous or rectally administered contrast material to make the procedure simple and fast for detection of this surgical emergency.

Among various signs of acute appendicitis at CT, increased appendiceal diameter is considered as the most precise sign with sensitivity and specificity of 92%-93% and 92%-100% respectively reported in the literature[6,7]. Secondary signs of inflammation also seen in many patients with acute appendicitis that help in the conclusion. However, appendiceal diameter enlargement can be seen as an isolated finding indicating acute appendicitis and has been reported in significant number (52%) of symptomatic patients[8].

In many text books of radiology and published articles on the topic of appendicitis, the upper limit for normal appendiceal thickness has been taken as 6 mm[2-9]. This was reported in the ultrasound literature mostly by assuming a graded compression technique. Since compression is not applied during CT scan studies this 6 mm threshold of appendix at ultrasound is difficult to hypothesize in interpretation of CT scans. Limited studies are available in literature in which normal appendix was evaluated and much less even on MDCT. The purpose of this study was to look for the frequency of visualization of appendix with assessment of position, diameter and luminal contents in patients not having any clinical suspicion of appendicitis as a primary provisional diagnosis.

This retrospective study included 110 adult subjects presenting to the Radiology Department of Dallah Hospital, Riyadh with complaint of hematuria, in whom there was no clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis. Twelve had history of appendectomy confirmed through review of medical record files of the patients and were omitted from the study group. The study period was from March 2013 to October 2013, and approval from ethics committee was obtained from the institutional review board of Dallah Hospital. Only the non-contrast CT scan for all patient was included in this review. Exclusion criteria included patients with other complaints, i.e., abdominal pain, fever. Patients with known pathologies centered in the right iliac fossa region were also excluded since diameter of appendix may be affected by inflammatory and neoplastic pathologies. All CT examinations were performed using Siemens SOMATOM Definition AS + 128 slice scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). The scan range extended from the superior pole of the most cephalic kidney to the base of the bladder. Following acquisition parameters were employed: Gantry rotation time of 300 milliseconds, 120 kVp, 190-280 reference mAS, collimation 128 mm × 0.6 mm. Calculated radiation dose for examination was around 4 mSV. Coronal and sagittal images were reconstructed with multiplanar technique having slice thickness of 2 mm and a reconstruction interval of 2 mm.

All images were stored and sent to the workstation (VEPRO, AG, Germany). Two radiologist with 8 and 10 years of experience in emergent abdominal imaging reviewed CT images with a standard mediastinal window settings (window width, 300 HU; window level, 40 HU) on picture archiving and communication system workstation.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 17; Chicago, IL, United States) Agreement between readers for identification of appendix on the basis of axial images alone or on the basis of combined axial and coronal images was determined using k statistic. The linear, weighted k statistic was applied for inter-observer agreement between the two radiologists. Agreement was rated poor (k < 0.00); slight agreement (0.00-0.20); fair agreement (0.21-0.40); moderate agreement (0.41-0.60); substantial agreement (0.61-0.80); almost perfect agreement (0.81-1.00). Chi-square test was used for comparing independent proportions, while McNemar test was applied for analyzing paired proportions. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For axial images alone, the normal appendix was identified in 93/98 of the subjects by Reader 1 and 95/98 of the subjects by Reader 2. For combined axial and coronal images, the normal appendix was identified in 97/98 of the subjects by both readers. Thus, the mean identification rate of the normal appendix was 94% with the axial images only, and 99% with both the axial and coronal images. Prevalence was 11% in this cohort (12 of 110 patients had undergone appendectomy).

For the axial images alone, agreement between the readers for identification of normal appendix was moderate (k = 0.43). However, the agreement was almost perfect (k = 0.85) when both axial and coronal images were reviewed.

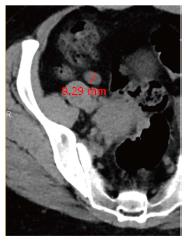

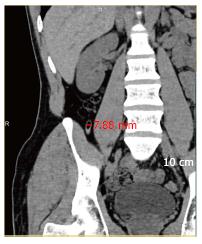

Table 1 describes the frequencies of visualization of a normal appendix in patients who had their appendix (sensitivity), the frequency of recognition of an absent appendix (specificity), the predictive value of visualization of the normal appendix (positive predictive value), and the predictive value of lack of visualization of an appendix(negative predictive value). Frequencies of visualization were obtained for axial images alone and with coronal reformations. The most common position of the appendiceal tip was medial (55%), followed by retro-caecal (26%), sub-hepatic (6%), pelvic (8%), and inferior (4%). Thirty percent of appendices were collapsed and did not contain any air, fecal matter or fluid. Fifty percent had intra luminal air only, 18% contained both air and fecal matter, while 2% had only fluid as luminal content. The minimum diameter of appendix encountered was 3.0 mm (Figure 1) with maximum of 11.0 mm (Figure 2). The mean outer diameter of the appendix was 5.6 ± 1.3 mm (diameter included both types of appendices that is when luminal contents were visualized and when contents were not visualized).

| Axial images | Axial + coronal reformations | |||||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | |

| Reader 1 | 95% (93/98) | 92% (11/12) | 94% (93/99) | 65 (11/17) | 99% (97/98) | 92% (11/12) | 99% (97/98) | 92% (12/13) |

| Reader 2 | 97% (95/98) | 100% (12/12) | 97% (95/98) | 80 (12/15) | 99% (97/98) | 100% (12/12) | 99% (97/98) | 92% (12/13) |

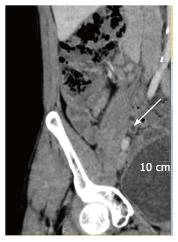

Table 2 shows the mean and the range of thickness of visualized 97 normal appendices for each reader separately and in combination. When the luminal contents were not visualized the full thickness was measured (Figure 3) outer wall-to wall diameter. The mean thickness of normal appendix was 6.6 ± 1.1 (SD) (range, 3.5-11.0). Forty-eight percent patients had outer diameter greater than 6.0 mm. When luminal contents were visualized the wall itself could be measured (Figure 4), the mean thickness of normal appendix was 3.9 ± 1.0 (range, 3.0-8.5). The one normal appendix (Figure 5) not detected by both readers despite coronal reformations was due to adjacent fluid distended bowel loops.

| Mean and range of the thickness of 97 normal appendices | ||||

| Appendix thickness | Reader 1 | Reader 2 | Combined | P value |

| With luminal contents | 3.6 ± 1.1 (3.0-8.0) | 4.2 ± 1.0 (2.8-9.0) | 3.9 ± 1.0 (3.0-8.5) | < 0.05 |

| Without luminal contents | 6.8 ± 1.5 (3.5-11.2) | 6.4 ± 1.3 (3.5-10.5) | 6.6 ± 1.1 (3.5-11.0) | > 0.50 |

Acute appendicitis is one of most common reason of acute abdominal emergency and usually diagnosed clinically. In pre cross-sectional imaging era, negative appendicectomy rate at histopathological examination was around 20%[10]. With wide spread use of imaging, population-based rates for negative appendectomy has remained unchanged over time[11]. Appendicitis now better diagnosed preoperatively, and results described in one study reported that the preoperative CT imaging in patients with an equivocal clinical appearance of suspected appendicitis leads to a marked reduction in the negative appendectomy rate to 4%[1]. CT evaluation is straight forward with either negative or positive answers. Both appendiceal enlargement and associated signs of inflammation are frequently present in appendicitis. At times, appendiceal enlargement is the only sign of appendicitis present in up to 12% of cases leading to unclear diagnosis at CT[8]. CT evaluation of appendicitis with oral and intravenous administration of contrast material continues to be commonly used. Although oral contrast administration has long been known as a useful method for delineating the normal appendix and diagnosing appendicitis, it has some disadvantage such as the delayed scan time, the lack of opacification of normal appendix, and poor tolerance in patients who are nauseous[12,13]. With availability of more recent 64-, 128- and even higher slice MDCT scanners the use of non-enhanced scanning without oral and intravenously administered contrast material is increasing. With new MDCT scanners, volumetric images of the appendix can be obtained using multiplanar reformations. Axial images alone have limitations in tracing the course of the appendix as it is a curved and tortuous structure, especially if the appendix is retrocaecal or pelvic in location[4]. Therefore, the coronal reformation images greatly assist in the tracing and demonstration of these appendices. Moreover, the coronal reformation images make it easy to visualize the entire anatomic configuration of the ileocaecal valve, the caecum and the base of the appendix, which helps in identification of the normal appendix [14]. In our study addition of coronal reformations to axial images significantly improved the inter-reader agreement in identifying normal appendix.

A normal appendix was identified in 73%-82% of patients who had undergone thin-section axial CT of the abdomen[15-17] , Jan et al[14] using 16-slice MDCT with multiplanar reformation images reported increase in the visualization of normal appendix to 93%. In another study by Kim et al[18] using 64-slice MDCT with coronal reformations reported an even higher identification rate of 98.5%. This being the highest rate of normal appendix visualization reported so far when compared to earlier studies. In our study the visualization of normal appendix on 128-slice MDCT is comparable to the 64-slice MDCT.

Levine et al[19] reported that factors such as paucity of intra-abdominal fat and the dilatation of small bowel in some cases could influence the false-negative diagnosis of appendicitis by CT. Similarly, the identification of the normal appendix by axial CT may be dependent on the amount of intra-abdominal fat and the small bowel dilatation. In our study scanty intra-abdominal fat did not significantly influence the visualization of normal appendix in any case, however one missed appendix was likely due to water distended adjacent small bowel loops in the pelvis. Previous literature has described that in up to 45% of patients, the normal appendix measures greater than 6 mm in outer wall-to wall diameter at CT[15,16]. In our study 48% patients had outer diameter greater than 6 mm. The range of outer diameter thickness of normal appendix in our study was 3.0-11 mm. The mean outer diameter of the appendix was 5.6 ± 1.3 mm, which included both types of appendices when luminal contents were visualized and when they were not separately seen. We therefore suggest that the diagnosis of appendicitis is non conclusive at CT, solely based on size criteria. Since patients in our study were not primarily sent for exclusion of appendicitis, this can not be specified in how many percent of patients with diagnosed acute appendicitis, the appendiceal diameter overlaps with the normal values noted in our study.

There were several limitations in our study. Firstly there was no reference standard to be used as a proof for a normal appendix. Secondly pathological correlation was unavailable as it is impossible to plan a study of normal appendix with pathological validation. However, since none of the subjects in our study population had abdominal symptoms or history of abdominal surgery it is fair to assume that all included in our study had normal appendices. Another limitation was that the rate of visualisation of appendix was not studied after administration of intravenous or enteric contrast agent. We did not consider this necessary since our outcomes were in agreement with those reported by Jacobs et al[20] and confirmed that intravenous contrast injection does not increase the rate of identification of a normal appendix. Likewise previous studies[16,21-24] showed high diagnostic performance in cases done without oral or enteric contrast. Third limitation was that patient characteristics such as influence of quantity of intraabdominal fat on the identification of normal appendix were not studied. Finally agreement between the readers was not expressed in terms of correctness and thus not used to quantify the readers’ diagnostic performance.

In conclusion, 128-slice MDCT with its multiplanar reformation display is extremely useful for visualization of normal appendix. The normal appendix is very variable in its position and diameter. In the absence of other signs, the diagnosis of acute appendix should not be made solely on outer appendiceal diameter. The importance of correlation with clinical and laboratory information also needs to be emphasized.

With recent advancement in computed tomography (CT) and availability of faster CT scanner like 128-slice multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) there is further improvement in image quality with reduced patient dose. The visualization of small structures like appendix became clearer and measuring outer-to-outer diameter became easier as seen in this series.

As appendicitis is one of most common surgical emergency prompting urgent and accurate diagnosis, the role of imaging will remain vital requiring more studies to enhance the accuracy of correct diagnosis.

128-Slice MDCT scan is extremely useful in visualization and evaluation of appendix hence one can confidently rule in or out acute appendicitis.

Outer-to-outer diameter alone cannot be used as sign of acute appendicitis so correlation with other signs is extremely important to avoid overcalling.

128-slice MDCT: 128 slice multidetector computed tomography scan.

The paper is well written and describes the results well. The conclusions are well founded.

| 1. | Rao PM, Rhea JT, Novelline RA, Mostafavi AA, Lawrason JN, McCabe CJ. Helical CT combined with contrast material administered only through the colon for imaging of suspected appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1275-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jeffrey RB, Laing FC, Townsend RR. Acute appendicitis: sonographic criteria based on 250 cases. Radiology. 1988;167:327-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simonovský V. Sonographic detection of normal and abnormal appendix. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Paulson EK, Jaffe TA, Thomas J, Harris JP, Nelson RC. MDCT of patients with acute abdominal pain: a new perspective using coronal reformations from submillimeter isotropic voxels. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Paulson EK, Harris JP, Jaffe TA, Haugan PA, Nelson RC. Acute appendicitis: added diagnostic value of coronal reformations from isotropic voxels at multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;235:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Choi D, Park H, Lee YR, Kook SH, Kim SK, Kwag HJ, Chung EC. The most useful findings for diagnosing acute appendicitis on contrast-enhanced helical CT. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ives EP, Sung S, McCue P, Durrani H, Halpern EJ. Independent predictors of acute appendicitis on CT with pathologic correlation. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Daly CP, Cohan RH, Francis IR, Caoili EM, Ellis JH, Nan B. Incidence of acute appendicitis in patients with equivocal CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1813-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rioux M. Sonographic detection of the normal and abnormal appendix. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:773-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Berry J, Malt RA. Appendicitis near its centenary. Ann Surg. 1984;200:567-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Flum DR, McClure TD, Morris A, Koepsell T. Misdiagnosis of appendicitis and the use of diagnostic imaging. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:933-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SY, Coughlin B, Wolfe JM, Polino J, Blank FS, Smithline HA. Prospective comparison of helical CT of the abdomen and pelvis without and with oral contrast in assessing acute abdominal pain in adult Emergency Department patients. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:150-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mun S, Ernst RD, Chen K, Oto A, Shah S, Mileski WJ. Rapid CT diagnosis of acute appendicitis with IV contrast material. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jan YT, Yang FS, Huang JK. Visualization rate and pattern of normal appendix on multidetector computed tomography by using multiplanar reformation display. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:446-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tamburrini S, Brunetti A, Brown M, Sirlin CB, Casola G. CT appearance of the normal appendix in adults. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:2096-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Benjaminov O, Atri M, Hamilton P, Rappaport D. Frequency of visualization and thickness of normal appendix at nonenhanced helical CT. Radiology. 2002;225:400-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Karabulut N, Boyaci N, Yagci B, Herek D, Kiroglu Y. Computed tomography evaluation of the normal appendix: comparison of low-dose and standard-dose unenhanced helical computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:732-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim HC, Yang DM, Jin W. Identification of the normal appendix in healthy adults by 64-slice MDCT: the value of adding coronal reformation images. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:859-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Levine CD, Aizenstein O, Lehavi O, Blachar A. Why we miss the diagnosis of appendicitis on abdominal CT: evaluation of imaging features of appendicitis incorrectly diagnosed on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:855-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA, Macari M, Megibow AJ, Israel G, Maki DD, Aguiar AM, Langlotz CP. Acute appendicitis: comparison of helical CT diagnosis focused technique with oral contrast material versus nonfocused technique with oral and intravenous contrast material. Radiology. 2001;220:683-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Keyzer C, Zalcman M, De Maertelaer V, Coppens E, Bali MA, Gevenois PA, Van Gansbeke D. Comparison of US and unenhanced multi-detector row CT in patients suspected of having acute appendicitis. Radiology. 2005;236:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ege G, Akman H, Sahin A, Bugra D, Kuzucu K. Diagnostic value of unenhanced helical CT in adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:721-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Birnbaum BA, Jeffrey RB. CT and sonographic evaluation of acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:361-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lane MJ, Liu DM, Huynh MD, Jeffrey RB, Mindelzun RE, Katz DS. Suspected acute appendicitis: nonenhanced helical CT in 300 consecutive patients. Radiology. 1999;213:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Parker W S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ