Published online Oct 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i10.840

Revised: September 18, 2014

Accepted: September 23, 2014

Published online: October 28, 2014

Processing time: 170 Days and 13.9 Hours

Pancreatic vipoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for less than 2% of endocrine pancreatic neoplasms with a reported incidence of 0.1-0.6 per million. While cross-sectional imaging findings are usually not specific, exact localization of the tumor by means of either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) is pivotal for surgical planning. However, cross-sectional imaging findings are usually not specific and further characterization of the tumor may only be achieved by somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy (SRS). We report the case of a 70 years old female with a two years history of watery diarrhoea who was found to have a solid, inhomogeneously enhancing lesion at the level of the pancreatic tail at Gadolinium-enhanced MR (Somatom Trio 3T, Siemens, Germany). The tumor had been prospectively overlooked at a contrast-enhanced multi-detector CT (Aquilion 64, Toshiba, Japan) performed after i.v. bolus injection of only 100 cc of iodinated non ionic contrast media because of a chronic renal failure (3.4 mg/mL) but it was subsequently confirmed by SRS. The patient first underwent a successful symptomatic treatment with somatostatin analogues and was then submitted to a distal pancreasectomy with splenectomy to remove a capsulated whitish tumor which turned out to be a well-differentiated vipoma at histological and immuno-histochemical analysis.

Core tip: Pancreatic vipoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for less than 2% of endocrine pancreatic neoplasms. While cross-sectional imaging findings are usually not specific, exact localization of the tumor by means of either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) is pivotal for surgical planning. We report the case of a 70 years old female with a two years history of watery diarrhoea who was found to have a solid, inhomogeneously enhancing lesion at the level of the pancreatic tail at Gadolinium-enhanced MR. The tumor had been prospectively overlooked at a contrast-enhanced multi-detector CT but it was subsequently confirmed by somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy. The patient first underwent a successful symptomatic treatment with somatostatin analogues and was then submitted to a distal pancreasectomy with splenectomy.

- Citation: Camera L, Severino R, Faggiano A, Masone S, Mansueto G, Maurea S, Fonti R, Salvatore M. Contrast enhanced multi-detector CT and MR findings of a well-differentiated pancreatic vipoma. World J Radiol 2014; 6(10): 840-845

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i10/840.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i10.840

Pancreatic vipomas are extremely rare tumors accounting for only 2% of all pancreatic endocrine neoplasms (PNENs) with an annual incidence estimated to be 0.1-0.6 per million[1]. They may show a malignant behaviour in up to 70% of cases, mostly with evidence of hepatic metastases at the time of the diagnosis[1].

From a clinical point of view the diagnosis of a pancreatic VIPoma is straightforward in typical cases presenting with the Verner-Morrison triad first described in 1958[2]. The syndrome, also named WDHA (Watery Diarrhoea, Hypokalaemia, Achlorhydria), is caused by the excessive production of the Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) which stimulates fluid and electrolyte secretion in the intestinal epithelium through the activation of cyclic adenosine mono-phosphate pathway[3].

As most endocrine pancreatic tumors appear as hyper-vascular nodular lesions at either contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR), cross-sectional imaging findings of pancreatic vipomas are usually not specific[4-7]. However, the role of both CT and/or MR is pivotal to localize the lesion and evaluate its size and anatomic relationships in view of a surgical approach which represents the standard of care[8]. In addition to conventional imaging modalities, somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy (SRS) has been advocated as the technique of choice to detect and stage pancreatic vipomas[9].

Herein we report a case of 70 years old female with a two-years history of watery diarrhoea refractory to medical therapy who was found to have a pancreatic vipoma at the level of the pancreatic tail which was first overlooked at a contrast-enhanced multi-detector CT, later shown by contrast-enhanced MR and subsequently confirmed by SRS.

A 70 years old woman was admitted to the Gastroenterology Unit of our University with a two years history of chronic diarrhoea (2-5/die evacuations of semi-shaped stools) refractory to medical therapy (Loperamide) with associated hypokaliemia (3 mmol/L).

The patient was also affected by chronic renal failure (creatinine 3.4 mg/dL) due to a insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism in treatment with replacement therapy (Levothyroxine 50 mcg/die) and electrolyte imbalance (serum calcium: 8.5 mg/dL; phosphate: 5.2 mg/dL) presenting with episodic disturbances of consciousness. Other laboratory findings were unremarkable.

Contrast-enhanced CT was performed with a multi-detector row equipment (Aquilion 64, Toshiba, Japan) using a detector configuration of 1 mm × 32 mm, a table feed of 36 mm/s and a gantry rotation time of 0.75 (pitch factor = 0.844), 3 mm slice thickness, 120 kVp and automatic dose modulation (Noise Index = 12.5). Arterial, pancreatic and portal venous phase acquisitions were performed with fix scan delays of 35, 55 and 80 s after i.v. bolus injection (3 cc/s) of only 100 cc of non ionic iodinated contrast media (Ultravist 370; Bayer, Berlin, Germany) followed by 200 cc of saline solution with a dual-head injector (Stellant Injection System, Medrad Inc., United States) and further hydration with 1.80 L of 0.9% NaCl solution as the patient had a diabetic nephropathy[10].

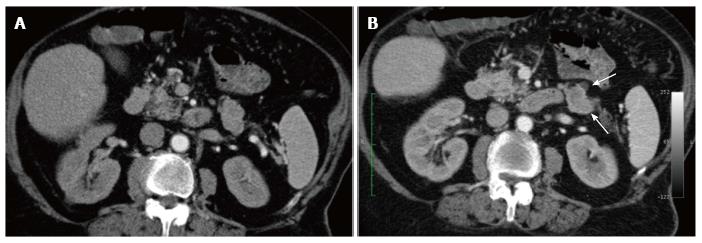

As both arterial and pancreatic phase imaging failed to show any hyper-vascular pancreatic lesion on prospective analysis (Figure 1), the patient went on to magnetic resonance imaging.

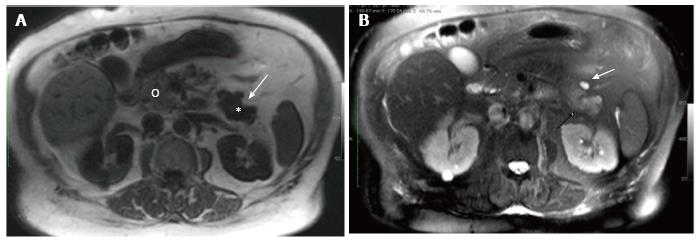

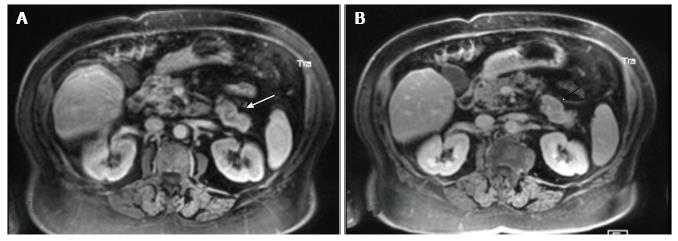

At unenhanced MR (Somatom Trio 3.0 T, Siemens, Germany) a definite oval lesion could be appreciated at the level of the pancreatic tail (Figure 2). The lesion exhibited non specific signal intensities appearing more conspicuous in the Fast Field Echo T1-images (TR: 1500 ms TE: 2 ms; FA: 20°; 6 mm slice thickness) with an uniform low signal intensity (Figure 2A) than in Half-fourier Acquisition Single-shot Turbo-spin Echo (HASTE) T2-sequences (TR: 2000 ms; TE: 92 ms; 6 mm slice thickness) where it showed a mild hyper-intense signal with an associated small cyst on its anterior margin (Figure 2B). Dynamic gadolinium-enhanced (0.1 mmol/kg, Gadoterate Meglumine, Guerbet, Switzerland) Volume Interpolated Breath-Hold Examination - (VIBE) Fat-suppressed T1 sequences (TR: 3.3 ms TE: 1.3 ms; 3 mm slice thickness, matrix size 256 × 224) were then performed and showed the lesion to enhance inhomogeneously in both the early (Figure 3A) and the delayed phase (Figure 3B).

As contrast-enhanced MR findings were considered consistent with an endocrine pancreatic tail tumor, a somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy was performed (not shown) and showed a mild uptake of the radiotracer at the level of the pancreatic tail with no evidence of either lymph node or hepatic metastases.

The patient underwent 3 mo of symptomatic therapy with somatostatin analogues (Octreotide 0.05 mg × 3/die) resulting in a complete remission of the diarrhea and was then submitted to a distal pancreasectomy with splenectomy by open surgery.

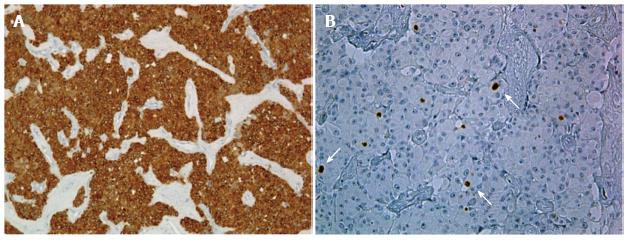

At histopathology, the pancreatic mass appeared as a circumscribed lesion with a solid growth pattern of small rounded, moderately pleo-morphic cells. Immunohistochemical analysis showed intense expression of neuroendocrine markers such as Chromogranine-A (Figure 4A) with less than 2% of cells positive for Ki-67 (Figure 4B).

The post-operative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged the weak after with a complete recovery of the syndrome and no evidence of residual or recurrent disease at follow-up CT performed yearly for 5 years.

PNENs formerly referred to as islet cell tumors[4,5] are rare neoplasms arising from ductal pluripotent stem cells of the pancreas[1]. Indeed PNENs represent only 3%-4% of all pancreatic neoplasms with a prevalence of approximately 1/100000[1].

Up to 30%-50% of PNENs are functioning neoplasms which manifest with typical clinical syndromes with insulinomas and gastrinomas being the most common followed by glucagonomas, somatostatinomas and vipomas[1]. These latter represent only 2% of functional PNENs and usually manifest with the classic WDHA syndrome first described by Verner et al[2] in 1958.

Such was the case of our patient who had a two years history of watery diarrhea which was thought to be related to an infective or a parasitic disease. However, further clinical and biochemical evaluation revealed the typical electrolyte alterations of the syndrome[3].

At this time, a multi-detector contrast-enhanced CT was performed but it failed to show any hyper-vascular pancreatic lesion on prospective analysis (Figure 1). As this was clearly a perceptive error, it could be largely explained by both the sub-optimal dose (100 cc) and rate (3 cc) of injection of the iodinated contrast media which had to be used because of the diabetic nephropathy of the patient[10]. Indeed, while most PNENs appear as hypervascular nodular lesions more conspicuous in the arterial phase of contrast-enhanced CT[5,7], these imaging features, commonly regarded as characteristic for PNENs, rely on tailored protocols in which the amount of iodinated contrast media and its rate of injection are of the utmost importance[5,11]. However, pancreatic endocrine tumors can occasionally appear isoattenuating to the surrounding parenchyma and can therefore be missed at contrast-enhanced CT[12].

As contrast-enhanced CT was considered not diagnostic, further imaging with MR had to be performed. Unenhanced MR showed a definite oval mass, hypo-intense in T1-FFE sequences (Figure 2A) and mildly hyper-intense in the HASTE-T2-weighted sequences (Figure 2B), at the level of the pancreatic tail (Figure 2). Although these signal intensities are commonly observed in pancreatic endocrine tumors, they are not specific[6,7]. Some endocrine tumors may indeed characteristically exhibit a low signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence as a result of their collagen content[4], but this was not the case of our patient.

As a result, further characterization with dynamic contrast-enhanced MR was deemed necessary. Despite the estimated glomerular filtration rate[13] was 23 mL/min, gadolinium-enhanced MR was considered a safe procedure using Gadoterate Meglumine, a Gadolinium-based contrast agent containing the macro-cyclic ligand Tetraazacyclo-dodecane-tetraacetic Acid[14]. Indeed, no case of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis has been reported to date following its use[14].

At contrast-enhanced MR the lesion exhibited a mild and inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase which could be appreciated despite the presence of motion artifacts (Figure 3A) with a rim of peripheral enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure 3B). Although similar enhancement patterns can also be observed in other neoplastic pancreatic lesions such as the acinar cell carcinoma[15] and the solid pseudopapillary tumor[16], MR findings were finally considered consistent with the diagnosis of a pancreatic vipoma as the patient had the typical symptoms of the Verner-Morison syndrome[2] and most vipomas are indeed localized at the level of the pancreatic tail[7].

As the tumor was prospectively missed on contrast-enhanced multi-detector CT, the present case underscores the relevance of a multidisciplinary approach in the detection of pancreatic neuro-endocrine tumors and the superior contrast resolution of MR which turns out to be particularly helpful whenever the administration of iodinated contrast media is either contraindicated or sub-optimal[17].

Contrast-enhanced MR findings were finally considered consistent with the diagnosis of a pancreatic vipoma and a SRS was then performed (not shown). Indeed, SRS has been advocated as the technique of choice to detect and stage pancreatic vipomas[9]. As SRS showed a mild uptake of the radiotracer at the level of the pancreatic tail, a successful treatment with a somatostatin analogue could then be undertaken[18].

The lesion was then successfully removed at surgery where it appear as an capsulated, whitish tumor. Immunohisto-chemical analysis showed intense and uniform staining with Chromogranin-A (Figure 4A) with less than 2% of cells positive with Ki-67 (Figure 4B) as usually observed in well-differentiated neuro-endocrine tumors, currently classified as well-differentiated vipoma (NET G1)[19].

Histological findings well accounted for the MR appearance of the lesion which was sharply marginated with an almost homogeneous signal intensity on both unenhanced sequences (Figure 2) and a ring enhancement in the delayed phase of dynamic post-Gadolinium sequence likely due to the presence of the capsule (Figure 3B).

We have herein reported contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography and MR imaging findings of a well differentiated pancreatic vipoma successfully treated by surgery with no signs of local recurrence and/or distant metastases at follow-up CT performed yearly for 5 years.

A 70 years old female with 2 years history of watery diarrhoea irresponsive to medical therapy.

The patient had typical symptoms, bio-chemical and pH-metric alterations of the Verner-Morison syndrome (Watery Diarrhoea, Hypokalaemia, Achlorhydria).

Infective or parasitic intestinal disease were excluded with stool examination, laboratory findings and colonoscopy.

Hypokalaemia (3 mmol/L, n.v. 3.5-5.3) and C/P imbalance [serum calcium: 8.5 mg/dL (n.v. 8.9-10.3); phosphate: 5.2 mg/dL (n.v. 3.0-4.5).

The lesion was prospectively overlooked at a contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) which had to be performed with a sub-optimal quantity and rate of injection of a non ionic iodinated contrast media because of a diabetic nephropathy (Serum creatinine 3.4 mg/mL). A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) was performed despite a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 23 mL/min and showed a well marginated oval lesion at the level of the pancreatic tail with non specific signal characteristics on unenhanced sequences and a ring-like enhancement in the delayed phase of post-Gadolinium sequences. Further characterization was obtained by Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy.

The lesion appeared as an capsulated, whitish tumor. Immunohisto-chemical analysis showed intense and uniform staining with Chromogranin-A with less than 2% of cells positive with Ki-67 as usually observed in well-differentiated neuro-endocrine tumors, currently classified as well-differentiated vipoma.

The patient underwent a 3 mo of symptomatic therapy with somatostatin analogues (Octreotide 0.05 mg × 3/die) resulting in a complete remission of the diarrhea and was then submitted to a distal pancreasectomy with splenectomy by open surgery.

A similar case of a functional pancreatic endocrine tumor overlooked at a contrast-enenhanced computed tomography (CT) has been reported. In that case it was an insulinoma of the pancreatic tail which appeared iso-attenuating to the surrounding parenchyma and was revealed by MR diffusion imaging.

The Verner-Morison syndrome, also named WDHA (Watery Diarrhoea, Hypokalaemia, Achlorhydria) is caused by the excessive production of the Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) which stimulates fluid and electrolyte secretion in the intestinal epithelium through the activation of cyclic adenosine mono-phosphate pathway.

Localization of a functional pancreatic endocrine tumor may be a challenge for a single imaging test and require most often a multi-modality approach. While characterization of such tumors may only be achieved by Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy, cross-sectional conventional (CT or MR) imaging modalities are pivotal for surgical planning.

The authors reported a case of pancreatic VIPomas that was overlooked on initial CT images and detected on MRI images. References to previous reports of underdiagnosis of such cases on CT images (or MRI) are required.

| 1. | Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:409-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Verner JV, Morrison AB. Islet cell tumor and a syndrome of refractory watery diarrhea and hypokalemia. Am J Med. 1958;25:374-380. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kane MG, O’Dorisio TM, Krejs GJ. Production of secretory diarrhea by intravenous infusion of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1482-1485. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Thoeni RF, Mueller-Lisse UG, Chan R, Do NK, Shyn PB. Detection of small, functional islet cell tumors in the pancreas: selection of MR imaging sequences for optimal sensitivity. Radiology. 2000;214:483-490. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Horton KM, Hruban RH, Yeo C, Fishman EK. Multi-detector row CT of pancreatic islet cell tumors. Radiographics. 2006;26:453-464. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Semelka RC, Custodio CM, Cem Balci N, Woosley JT. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: spectrum of appearances on MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:141-148. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lewis RB, Lattin GE, Paal E. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: radiologic-clinicopathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30:1445-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ellison TA, Edil BH. The current management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Adv Surg. 2012;46:283-296. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Thomason JW, Martin RS, Fincher ME. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: the definitive technique for characterizing vasoactive intestinal peptide-secreting tumors. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:661-664. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Stacul F, van der Molen AJ, Reimer P, Webb JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Almén T, Aspelin P, Bellin MF, Clement O. Contrast induced nephropathy: updated ESUR Contrast Media Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:2527-2541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Camera L, Paoletta S, Mollica C, Milone F, Napolitano V, De Luca L, Faggiano A, Colao A, Salvatore M. Screening of pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumours in patients with MEN 1: multidetector-row computed tomography vs. endoscopic ultrasound. Radiol Med. 2011;116:595-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Anaye A, Mathieu A, Closset J, Bali MA, Metens T, Matos C. Successful preoperative localization of a small pancreatic insulinoma by diffusion-weighted MRI. JOP. 2009;10:528-531. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Delanaye P, Cohen EP. Formula-based estimates of the GFR: equations variable and uncertain. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;110:c48-53; discussion c54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Almén T, Bellin MF, Bertolotto M, Bongartz G, Clement O, Leander P, Heinz-Peer G, Reimer P. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast media: updated ESUR Contrast Medium Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:307-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hsu MY, Pan KT, Chu SY, Hung CF, Wu RC, Tseng JH. CT and MRI features of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with pathological correlations. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:223-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yao X, Ji Y, Zeng M, Rao S, Yang B. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: cross-sectional imaging and pathologic correlation. Pancreas. 2010;39:486-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Balachandran A, Tamm EP, Bhosale PR, Patnana M, Vikram R, Fleming JB, Katz MH, Charnsangavej C. Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:342-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oberg K, Kvols L, Caplin M, Delle Fave G, de Herder W, Rindi G, Ruszniewski P, Woltering EA, Wiedenmann B. Consensus report on the use of somatostatin analogs for the management of neuroendocrine tumors of the gastroenteropancreatic system. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:966-973. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Klöppel G. Classification and pathology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18 Suppl 1:S1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Triantopoulou C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ