Published online Aug 28, 2013. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i8.321

Revised: July 7, 2013

Accepted: August 4, 2013

Published online: August 28, 2013

Processing time: 114 Days and 0.2 Hours

We report a case of Krukenberg tumor of gastric origin with adnexal metastasis, in which ultrasonography (US) and contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) played a key diagnostic role. An 64-year-old female patient was referred to our department for abdominal pain, nausea and ascites. US examination was performed as first line diagnostic imaging approach, confirming the presence of ascites and detecting marked thickness of the gastric wall and a right adnexal mass. CEUS was immediately performed and showed arterial enhancement followed by wash-out in the venous phase of both the gastric wall and the adnexal mass, suggesting the diagnosis of gastric cancer with right adnexal metastasis (Krukenberg syndrome). The patient underwent US-guided paracentesis and esophagogastroduodenoscopy that showed linitis plastica. Cytologic examination of the peritoneal fluid revealed the presence of signet-ring cells, and histologic examination of the specimen obtained by endoscopic biopsy showed primary gastric mucus-producing adenocarcinoma with signet-ring cells. Although transvaginal US is undoubtedly the method of choice to evaluate ovarian tumors, abdominal US and CEUS can provide key diagnostic elements, supporting clinicians in the first steps of the diagnostic work-up of abdominal and pelvic masses.

Core tip: Transvaginal ultrasonography (TV-US) is the method of choice to evaluate ovarian tumors, but abdominal US enables to detect masses in both upper and lower abdomen, providing useful information when Krukenberg tumor is suspected. Moreover, contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) can be immediately performed to define the microvascularisation of the lesions, and the presence of arterial enhancement followed by wash-out in the venous phase is strongly suspicious of malignancy. US and CEUS can provide key diagnostic elements, supporting clinicians in the first steps of the diagnostic work-up of abdominal and pelvic masses.

- Citation: Tombesi P, Vece FD, Ermili F, Fabbian F, Sartori S. Role of ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in a case of Krukenberg tumor. World J Radiol 2013; 5(8): 321-324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i8/321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i8.321

Krukenberg tumor is defined as metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma originating from a primary tumor of the gastrointestinal tract and showing typical mucin-filled signet-ring cells[1-4]. Sometimes, metastatic ovarian tumors are detected before the primary lesion is diagnosed. Transabdominal ultrasonography (US) and trasvaginal US are used as first-line diagnostic techniques to evaluate most pelvic masses. However, their accuracy in differentiating benign from malignant masses is considered low, and further imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are usually necessary to obtain a reliable diagnosis.

We report a case in which transabdominal US and contrast-enhanced US (CEUS), performed as first diagnostic investigations, played a key role in the diagnostic work-up, promptly suggesting the correct diagnosis of Krukenberg tumor and its origin from a gastric cancer.

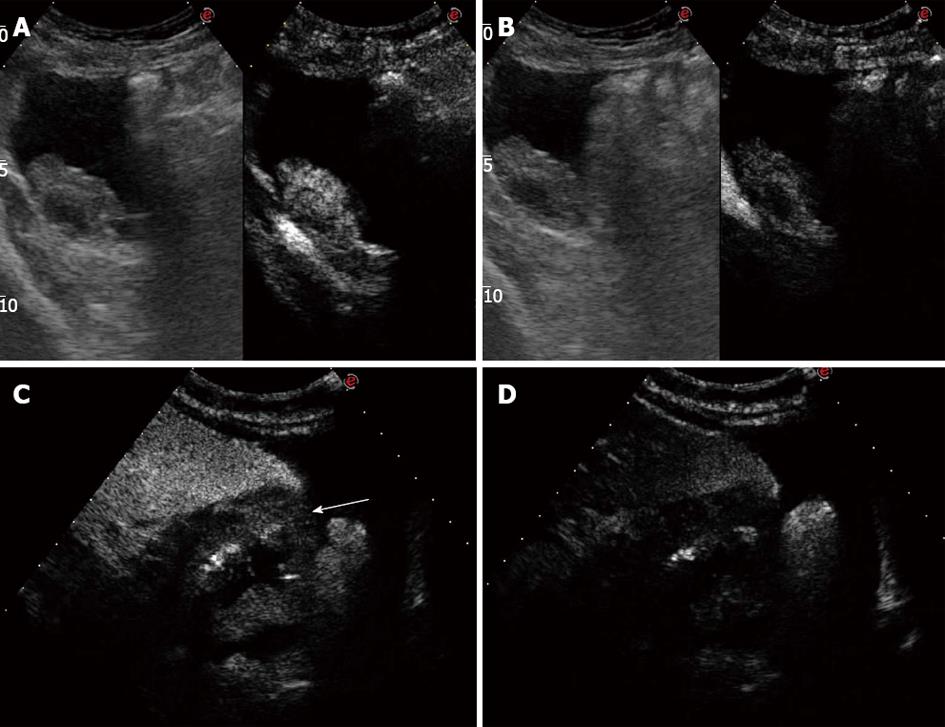

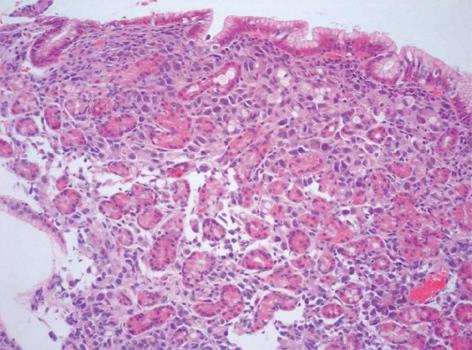

An 64-year-old female patient was admitted to our department for abdominal pain and nausea. Physical examination suggested the presence of ascites, and the patient underwent abdominal US. US examination was performed with a real-time sonography system equipped with a 3.5-5.0 MHz convex transducer (Mylab 70 XVG; Esaote Medical Systems, Genova, Italy). US scans confirmed the presence of ascites, showed marked thickness of the gastric wall with the typical target pattern defined as “pseudokidney” (Figure 1A), lymph-node enlargement nearby the pancreas and aorta, and bilateral hydronephrosis. US examination was extended to the lower abdomen, and a 6 cm × 2.5 cm inhomogeneously hyperechoic mass with irregular borders was detected in the right adnexal region (Figure 1B). The patient immediately underwent contrast enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) to better define the vascularisation of both the adnexal lesion and gastric wall. CEUS was performed with a low mechanical index contrast-specific nonlinear technique (CnTI, Esaote, Genova, Italy), and an 8 microliters/mL solution of sulfur hexafluoride microbubbles stabilized by a phospholipid shell (SonoVue®, Bracco, Milan, Italy) was used as US contrast agent. After intravenous injection of a bolus of 2.4 mL of SonoVue, the adnexal mass showed inhomogeneous contrast enhancement in the arterial phase followed by moderate wash-out in the venous phase (Figure 2A and B). The gastric wall had similar CEUS behavior, with enhancement in the arterial phase and marked wash-out in the venous phase (Figure 2C and D). Based on both US and CEUS findings, the diagnosis of gastric cancer with right adnexal metastasis (Krukenberg syndrome) was inferred, and the patient underwent US-guided paracentesis for cytological examination and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS). Cytologic examination of the peritoneal fluid documented the presence of signet-ring cells, and EGDS showed stiffness and thickening of the gastric mucosal folds with mosaic pattern and multiple nodular lesions suggestive of linitis plastica (Figure 3). Endoscopic biopsy revealed poorly differentiated primary gastric mucus-producing adenocarcinoma with signet-ring cells (Figure 4).

Krukenberg tumors are metastatic ovarian tumors from primary lesions in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly from carcinomas of the colon and stomach. The term “Krukenberg tumor” has been used either as a broad term to indicate all metastatic tumors to the ovaries or to describe just metastatic tumors from the gastrointestinal tract containing the typical signet ring cell with intracellular mucin[1-4]. The presence of ovarian metastases represents a poor prognostic sign, and a prompt aggressive therapy is beneficial for both quality of life and symptom relief. US is usually used as the first imaging approach to evaluate pelvic masses[5,6]. However, although it can reliably differentiate cystic lesions from solid masses, CT and MRI are considered the techniques of choice to characterize ovarian tumors[7,8]. Moreover, gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations are needed to identify the primary tumor. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of Krukenberg syndrome inferred on the basis of US and CEUS findings. Low mechanical index CEUS with second generation US contrast agents is a well established technique for the characterization of liver tumors as well as for the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant lesions of other abdominal organs such as the kidney and pancreas. In particular, the presence of wash-out in the late venous phase is considered strongly suspicious of malignancy. Conversely, data about the role of CEUS in the characterization of pelvic masses are still lacking in literature. Some preliminary reports suggested that CEUS can differentiate invasive ovarian tumors from benign and borderline tumors but it is not reliable in differentiating benign from borderline tumors[9]. Even though US and CT findings of Krukenberg tumor are quite indistinguishable from those of primary ovarian cancer, the detection of a solid or mixed cystic ovarian mass accompanied with a suspicious gastrointestinal mass should be regarded as a metastatic tumor until proven otherwise. In our patient, US detected both the adnexal mass and thickening of the gastric wall with “pseudokidney” pattern. CEUS documented the presence of contrast enhancement in the arterial phase followed by wash-out in the late venous phase in both the ovarian mass and gastric wall that is the typical CEUS behavior of malignant lesions of the liver and other abdominal organs. Based on these findings, gastric cancer with metastatic ovarian spread was strongly suspected, and the patient was promptly referred for EGDS, which yielded the definitive diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. Moreover, US-guided paracentesis documented the presence of signet-ring cells in the ascitic fluid, suggesting the peritoneal spread of the gastric cancer.

If confirmed by further reports, our observation could be of some interest in the diagnostic work-up of incidental adnexal masses. Although transvaginal sonography is undoubtedly the method of choice to evaluate ovarian tumors, transabdominal US allows to extent the examination throughout the abdomen to search for primary tumors in other organs, and CEUS enables to depict the vascular pattern of the lesions. In our opinion, such capabilities could play some useful role when a metastatic disease is suspected.

| 1. | WOODRUFF JD, NOVAK ER. The Krukenberg tumor: study of 48 cases from the ovarian tumor registry. Obstet Gynecol. 1960;15:351-360. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mazur MT, Hsueh S, Gersell DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:1978-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ulbright TM, Roth LM, Stehman FB. Secondary ovarian neoplasia. A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:1164-1174. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Russel P, Bannatyne P. Surgical pathology of the ovaries. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 1989; 474-501. |

| 5. | Rochester D, Levin B, Bowie JD, Kunzmann A. Ultrasonic appearance of the Krukenberg tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:919-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Athey PA, Butters HE. Sonographic and CT appearance of Krukenberg tumors. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cho KC, Gold BM. Computed tomography of Krukenberg tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:285-288. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ha HK, Baek SY, Kim SH, Kim HH, Chung EC, Yeon KM. Krukenberg’s tumor of the ovary: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1435-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Testa AC, Timmerman D, Van Belle V, Fruscella E, Van Holsbeke C, Savelli L, Ferrazzi E, Leone FP, Marret H, Tranquart F. Intravenous contrast ultrasound examination using contrast-tuned imaging (CnTI) and the contrast medium SonoVue for discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses with solid components. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer Kabaalioglu A S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Liu XM