Revised: August 21, 2012

Accepted: January 31, 2013

Published online: March 28, 2013

Sonohysterography (SHG), which provides enhanced endometrial visualization during standard transvaginal ultrasonography, is a relatively safe procedure for the evaluation of endometrial pathology. It can be used to evaluate patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding or infertility. This modality offers real time imaging of the endometrium without exposure to ionizing radiation. SHG is typically used in patients for whom standard transvaginal ultrasonography does not show the endometrium well, show a potential abnormality for which further imaging is required, or in patients without endometrial pathology defined on routine transvaginal imaging but in whom there is a strong clinical suspicion of an abnormality. This article will discuss the utility of the sonohysterogram in evaluation of various endometrial pathologies. Imaging examples of these pathological entities will be illustrated as well.

- Citation: Yang T, Pandya A, Marcal L, Bude RO, Platt JF, Bedi DG, Elsayes KM. Sonohysterography: Principles, technique and role in diagnosis of endometrial pathology. World J Radiol 2013; 5(3): 81-87

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i3/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i3.81

Sonohysterography (SHG) enhances the endometrial visualization achieved with standard transvaginal ultrasonography[1,2]. It serves as a supplementary methodology to transvaginal ultrasound to better evaluate the endometrium. Specifically, it entails instillation of normal saline into the endocervical canal (Figure 1) to enhance detection of endometrial abnormalities, further define potential abnormalities initially detected by standard transvaginal ultrasonography[3], and evaluate anatomical causes of infertility, namely submucosal myomas, endometrial polyps, anomalies and intrauterine adhesions[1,2,4-8]. Distension of the endometrial cavity in patients with endometrial stripes too difficult to detect on transvaginal ultrasound can enable the radiologist to better visualize and characterize pathologies.

SHG is typically used to determine the cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding in both pre- and postmenopausal patients[3,4]. In premenopausal women with dysfunctional vaginal bleeding, SHG’s clinical utility lies in its ability to distinguish anovulatory bleeding from an anatomical lesion. In postmenopausal women with abnormal vaginal bleeding, SHG can distinguish between atrophy and an anatomical lesion which may require biopsy. Key indications for SHG include abnormal uterine bleeding; infertility and repeated abortion; congenital abnormality of the uterine cavity; preoperative or postoperative evaluation of uterine myomas, polyps or cysts; suspected uterine synechiae; further evaluation of suspected endometrial abnormalities detected by transvaginal sonogram; and inadequate imaging by transvaginal sonography. The main contraindications of SHG include pregnancy, pelvic infection and excessive vaginal bleeding[3,4].

SHG ideally should be performed early in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (after cessation of menstrual flow) before day 10 because the endometrium is thin at this point[9]. A thin endometrium is critical so that the saline can more easily distend the uterine cavity and better accentuate endometrial pathology. Furthermore, irregularities in the contour of the endometrium may be misinterpreted as small polyps or focal areas of endometrial hyperplasia.

Although anesthesia or analgesia is not required for SHG, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may be offered 30 min prior to examination to help reduce the pain of cramping. A negative pregnancy test must be obtained from the patient before SHG commences.

The patient is placed in the lithotomy position. After applying betadine to the cervix, a speculum is inserted into the vaginal introitus and the cervical os is localized and cleaned with povidone iodine solution. A 5 to 7 French catheter is inserted through the cervical os and into the cervical canal, taking care to evacuate air bubbles first. The catheter balloon tip is then inflated using 1-2 mL of saline. The speculum is subsequently removed. A standard transvaginal ultrasound probe is then inserted alongside the catheter. Warm sterile saline is instilled into the endometrial cavity via a 20 mL syringe attached to the catheter while the transducer is moved from side to side (cornua to cornua) in a long axis position. The amount of fluid instilled will vary depending on distention of the uterus and patient tolerance. Usually, the amount of saline instilled is 40 mL. More fluid is instilled to obtain a detailed survey of the endometrium. Ideally, all portions of the endometrium should be imaged to exclude any abnormalities.

Common technical difficulties in performing SHG include variable uterine position, which can complicate catheter insertion; cervical stenosis, which may require cervical dilatation or even the use of a guidewire; and inhibited visualization of the endocervical canal[10]. To overcome difficulties in catheter insertion, one can change the toe of the speculum by moving the handle of the speculum up or down, thus changing the angle of access to the cervix. This maneuver will often enable successful catheter insertion. In patients with cervical stenosis, a cervical dilator may be used and the catheter inserted as described above. Alternatively, a guidewire can be passed through the cervical os and then pass the catheter without a balloon tip over the guidewire into the cervical os. Distension of the endocervical canal is a difficult task which can be obtained by synchronous gentle collapse of the catheter balloon while slowly instilling fluid into the canal while retracting the catheter or passively slipping it out of the uterus.

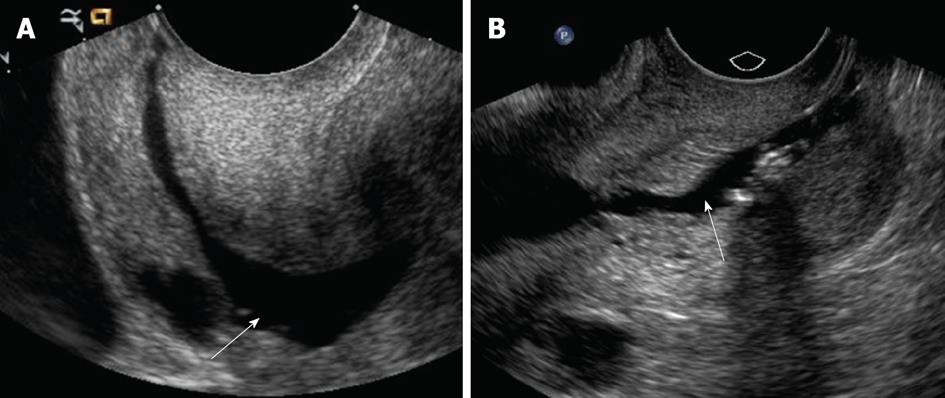

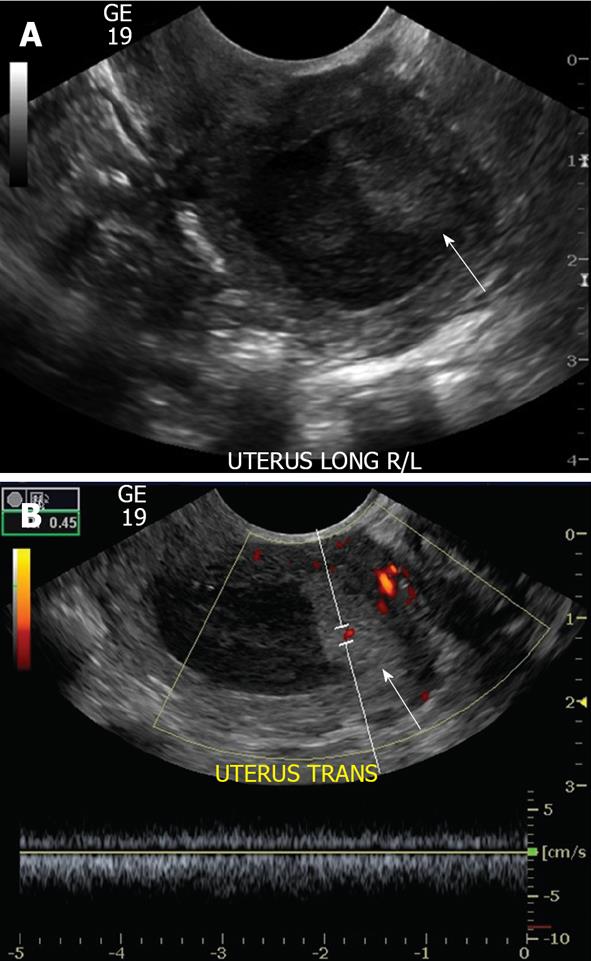

Air may be accidentally introduced into the endometrial canal, leading to an echogenic artifact that can obscure abnormalities; this artifact can be overcome by flushing the catheter with saline before the procedure[11]. Another pitfall that may occur is backflow of saline from around the balloon and out through the cervix of the injected saline, resulting in nondistension of the uterine cavity (Figure 2A). If this occurs, under distension of the uterine cavity can result in masking of endometrial pathology. Saline backflow can be reduced by gently retracting the inflated catheter balloon to occlude the internal cervical os. Balloon hyperinflation may obscure an underlying pathology (Figure 2B); to resolve this problem, one may need to move or partially deflate the balloon. With regard to potential insufficient examination from overdistension of the endometrial cavity, no complications have been described.

Based on a prospective study of 1153 patients who underwent SHG, complications have been documented. Complications of SHG include failure to complete the procedure owing mainly to patient noncompliance (7% of patients), pelvic pain (3.8% of patients), vagal symptoms (3.5% of patients), nausea (1% of patients) and post procedure fever (0.8% of patients)[9]. Preprocedurally, non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs and antibiotics may be administered to reduce complications. Reasons for an inability to complete the procedure include the presence of a stenotic cervix and cervical scarring causing backflow of saline. Given that SHG is a relatively safe procedure, mortality has not been described.

The goal of SHG is twofold: (1) to determine if the cavity is normal or abnormal; and (2) to determine if an abnormality is diffuse or focal. Hence, if no abnormality is present, no further workup may be needed. If an abnormality is focal, then direct visualization via hysteroscopy and image guided biopsy may be required for adequate sampling of the tissue as blind dilation and curettage may miss a focal lesion. If an abnormality is diffuse, dilatation and curettage alone may be employed without the need for hysteroscopically-guided biopsy.

A normal uterine cavity should expand symmetrically upon saline instillation. The endometrial lining appears smooth, with symmetric depth to both sides of the canal.

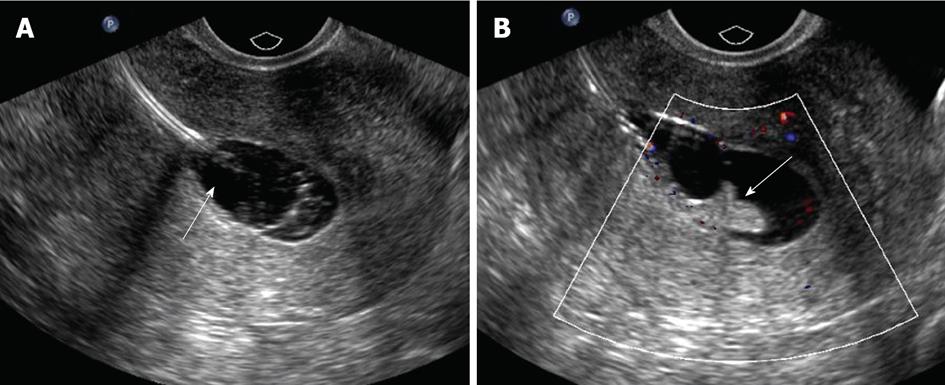

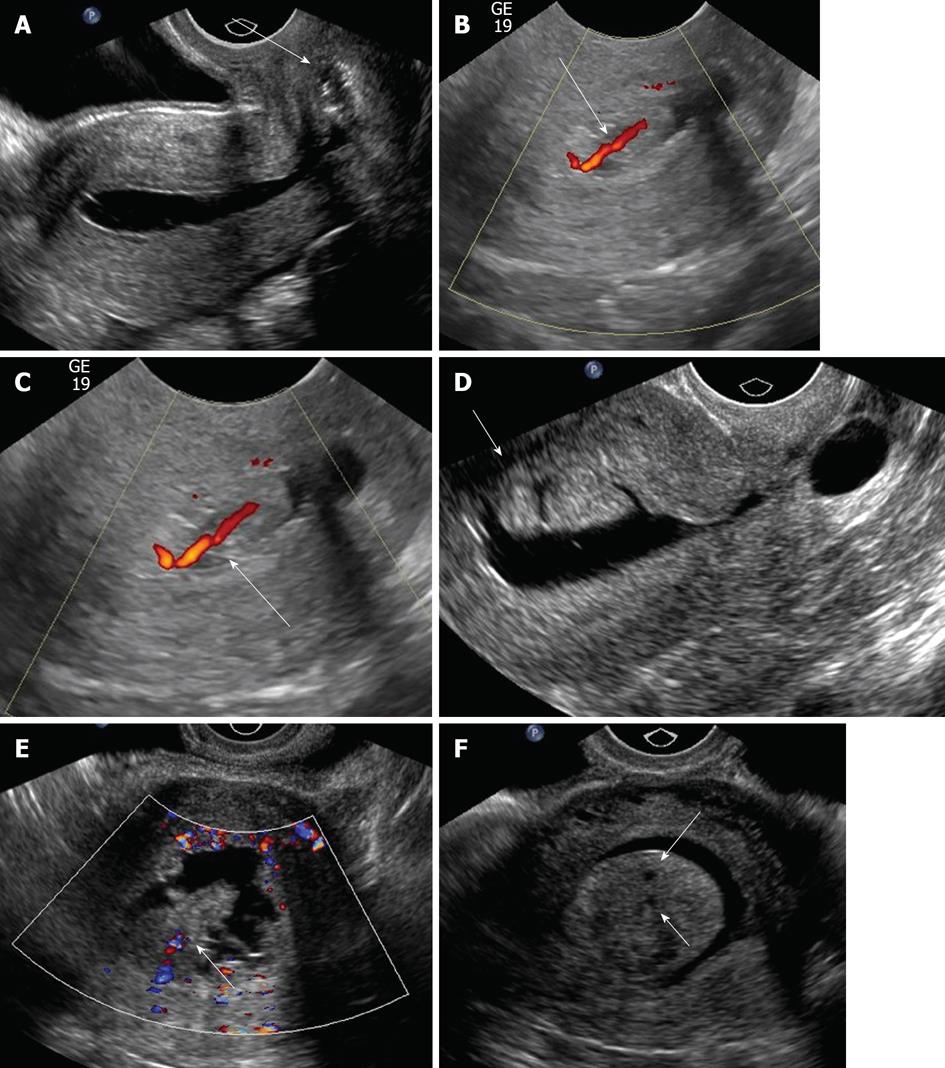

Various pathologies have been described to involve the endometrium. Endometrial polyps are localized hyperplastic overgrowths of endometrial glands and stroma that project beyond the surface of the endometrium. Ten percent of women develop endometrial polyps, with a peak incidence in women 40-49 years of age, but polyps can be seen in postmenopausal patients[12]. They are often soft and pliable and may present as single or multiple lesions. They usually arise from the fundus. They may be sessile or pedunculated. They may harbor malignancy, which may only be microscopic in extent, and thus SHG cannot exclude malignancy in any polypoid lesion.

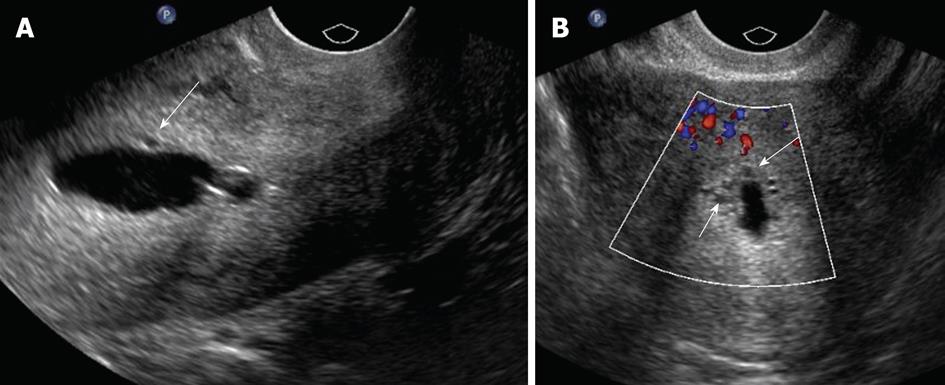

The typical sonographical appearance of an endometrial polyp is that of a well-circumscribed homogeneous lesion that is isoechoic to the endometrium (Figure 3A) yet preserves the endometrial-myometrial interface[10]. Using Doppler ultrasound interrogation, a feeding vessel often can be seen. The finding is nonspecific, however, in that atypical fibroids or endometrial cancer can demonstrate this appearance. However, endometrial polyps may have a single feeding vessel, while submucosal fibroids frequently have multiple feeding vessels (Figure 3B and C)[13]. Endometrial polyps can present in diverse manifestations (Figure 3D-F). Namely, they can present as cervical polyps, polyps with feeding vessels, multiple polyps or polyps with cystic change. A less common manifestation is a polyp with a broad base of attachment, a polyp which contains cystic components, or a polyp which contains areas of hypoechogenicity/heterogeneity within the polyp.

Submucosal leiomyoma is a common source of abnormal dysfunctional uterine bleeding and may cause reproductive dysfunction in the form of recurrent miscarriage, infertility, premature labor and fetal malpresentations[11]. Ten percent of submucosal leiomyomas present as postmenopausal bleeding.

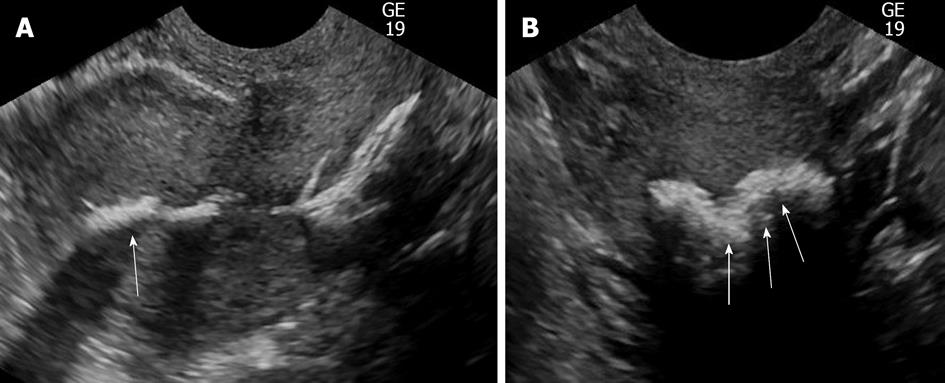

Submucosal leiomyomas typically appear as well-circumscribed, broad-based, hypoechoic masses that distort the endometrial-myometrial interface and give rise to refractile shadowing on ultrasound[10] (Figure 4). SHG can help estimate the percentage circumference projecting into the endometrial cavity[12]. If it involves greater than 50% of volume into the endocervical canal, hysteroscopic resection is generally considered. Atypical appearances include pedunculation or multilobulation, as well as prolapse into the endocervical canal, which may preclude SHG[14,15]. Open or laparoscopic myomectomy is likely needed with less than 50% protrusion. However, uterine fibroid embolization may also be an alternative. Sonohysterogram collectively has a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 95% in diagnosing all endometrial pathologies[16]. MRI has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 72% in diagnosing submucosal leiomyoma[17].

Endometrial hyperplasia is a proliferative disorder of the endometrial glands that results from unopposed estrogenic stimulation. It accounts for 4% to 8% of cases of endometrial bleeding. Histologically, the disorder is seen as a proliferation of endometrial glands of irregular size and shape, with an increase in gland-stroma ratio[7] that ranges from hyperplasia without atypia to severe atypia. With greater complexity of the architecture comes the greater the risk of cancer development. Risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia include unopposed estrogen exposure, tamoxifen usage, obesity, hypertension and diabetes.

Sonographically, endometrial hyperplasia usually appears as a diffuse irregular echogenic endometrial thickening without focal abnormality (Figure 5). However, it can be focal and impossible to distinguish from an endometrial polyp at HSG.

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecological cancer in the United States. Because it is typically detected in its early stages, endometrial carcinoma represents only 1.5% of cancer deaths. It usually occurs in postmenopausal women presenting with postmenopausal bleeding, with a peak in the sixth decade of life. Biopsy is mandatory to make this diagnosis.

SHG appearances of endometrial cancer can be variable. Sonographically, endometrial carcinoma typically presents as a diffuse, heterogeneous lobulated mass (Figure 6). However, a focal pattern may also be encountered. Endometrial carcinoma often distorts the endometrial-myometrial surface. It should be noted that endometrial carcinoma lesions can represent a microscopic focus in a polyp or can be small and polypoid and impossible to distinguish from polyps at HSG.

Adenomyosis is a nonneoplastic gynecological disease characterized by the migration of endometrial glands from the basal endometrial layer into the endometrium which is frequently associated with smooth muscle hyperplasia. Adenomyosis occurs most frequently in multiparous women with presenting symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea. Ectopic glands are located at least 2-3 mm from the endometrial-myometrial junction. Adenomyosis may cause asymmetric thickening of the uterus.

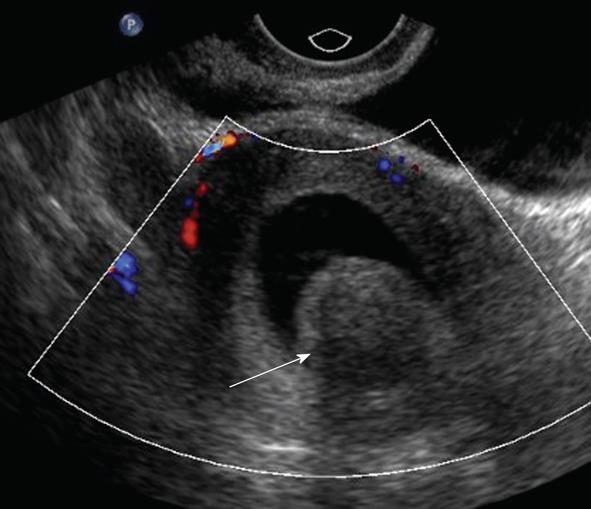

Diffuse globular uterine enlargement is a common sonographic manifestation of adenomyosis. Focal adenomyosis is typically manifested on ultrasound as small cystic areas in the subendometrial region of the myometrium (Figure 7). It should be noted that MRI may also be used to diagnose adenomyosis. MRI has a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 86% in diagnosing adenomyosis[18]. Sonohysterogram collectively has a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 95% in diagnosing all endometrial pathologies[16].

Adhesions will typically appear as mobile, thin, echogenic bands crossing the endometrial cavity. Less commonly, they appear as thick, broad-based bridging bands. Distending the endometrial cavity may be difficult in cases involving severe adhesions. Adhesions may be associated with scars, which can range from small echogenic areas of focal thickening to large regions of denuded endometrium. Adhesions are often a cause of infertility or recurrent abortion. Because they are likely compressed within the endometrial cavity, they are not easily detected on transvaginal ultrasound.

Endometrial osseous metaplasia is a rare abnormality which involves bone formation within the uterus. It is usually associated with recent abortion or chronic endometritis.

On SHG, endometrial osseous metaplasia often appears as diffuse echogenic involvement of the endometrium with posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 8). Calcified fibroids, however, are not usually a differential diagnostic problem as endometrial osseous metaplasia is rare.

Tamoxifen is used as an adjunctive treatment in breast cancer for its antiestrogenic effects. However, because of its estrogenic effects on the endometrium, transvaginal ultrasound and SHG may be needed to monitor for endometrial cancer, endometrial polyps or endometrial hyperplasia. The most common finding in women taking tamoxifen is endometrial thickening with cystic spaces[19]. However, cystic changes may occur in the inner myometrium.

From a management perspective, if a patient on tamoxifen is found to have a thickened endometrium measuring greater than 8 mm, biopsy may be indicated. A focal abnormality should lead to hysteroscopic resection while a diffuse abnormality may undergo non image guided biopsy[20]. Tamoxifen is reported to have an increased incidence of adenomyosis and leiomyomas.

SHG plays an important role in the workup of abnormal vaginal bleeding or incidental intracavitary lesions found on routine pelvic ultrasonography. Transvaginal ultrasonography alone provides only a limited evaluation of the endometrium. The use of optimal SHG techniques, including appropriate balloon inflation, location and endometrial and endocervical canal distension, can preclude the technical pitfalls of SHG and improve visualization of the endometrium, allowing more accurate delineation of various endometrial pathologies.

| 1. | Parsons AK, Lense JJ. Sonohysterography for endometrial abnormalities: preliminary results. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Syrop CH, Sahakian V. Transvaginal sonographic detection of endometrial polyps with fluid contrast augmentation. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:1041-1043. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Goldstein RB, Bree RL, Benson CB, Benacerraf BR, Bloss JD, Carlos R, Fleischer AC, Goldstein SR, Hunt RB, Kurman RJ. Evaluation of the woman with postmenopausal bleeding: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound-Sponsored Consensus Conference statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1025-1036. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Goldstein SR, Zeltser I, Horan CK, Snyder JR, Schwartz LB. Ultrasonography-based triage for perimenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salle B, Gaucherand P, de Saint Hilaire P, Rudigoz RC. Transvaginal sonohysterographic evaluation of intrauterine adhesions. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:131-134. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Darwish AM, Youssef AA. Screening sonohysterography in infertility. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48:43-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alborzi S, Dehbashi S, Parsanezhad ME. Differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus by sonohysterography eliminates the need for laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:176-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alatas C, Aksoy E, Akarsu C, Yakin K, Aksoy S, Hayran M. Evaluation of intrauterine abnormalities in infertile patients by sonohysterography. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:487-490. [PubMed] |

| 9. | O’Neill MJ. Sonohysterography. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:781-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lane BF, Wong-You-Cheong JJ. Imaging of endometrial pathology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:57-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dessole S, Farina M, Rubattu G, Cosmi E, Ambrosini G, Battista Nardelli G. Side effects and complications of sonohysterosalpingography. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:620-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grønlund L, Hertz J, Helm P, Colov NP. Transvaginal sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of female infertility, habitual abortion or metrorrhagia. A comparative study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:415-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fleischer AC, Shappell HW. Color Doppler sonohysterography of endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:601-604. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Davis PC, O‘Neill MJ, Yoder IC, Lee SI, Mueller PR. Sonohysterographic findings of endometrial and subendometrial conditions. Radiographics. 2002;22:803-816. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sohaey R, Woodward P. Sonohysterography: technique, endometrial findings, and clinical applications. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1999;20:250-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Alborzi S, Parsanezhad ME, Mahmoodian N, Alborzi S, Alborzi M. Sonohysterography versus transvaginal sonography for screening of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schwartz LB, Zawin M, Carcangiu ML, Lange R, McCarthy S. Does pelvic magnetic resonance imaging differentiate among the histologic subtypes of uterine leiomyomata. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:580-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Sørensen JS, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:588-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lev-Toaff AS, Toaff ME, Liu JB, Merton DA, Goldberg BB. Value of sonohysterography in the diagnosis and management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Radiology. 1996;201:179-184. [PubMed] |

| 20. | O’Connell LP, Fries MH, Zeringue E, Brehm W. Triage of abnormal postmenopausal bleeding: a comparison of endometrial biopsy and transvaginal sonohysterography versus fractional curettage with hysteroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:956-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer Andersen PE S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM