Published online May 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i5.228

Revised: April 13, 2012

Accepted: April 20, 2012

Published online: May 28, 2012

A 10-year-old girl presented with a mildly tender mass in the right preauricular region. The mass became larger, and the overlying skin turned purple. There was no clinical response to a course of either cephalexin or clarithromycin. The remainder of the head and neck examination was normal including normal facial nerve function. Lyme titers and a computed tomographic (CT) scan with contrast of the facial region were obtained. The CT scan demonstrated the lesion to be superficial to the parotid gland. The lyme titer was elevated and doxycycline was begun. The mass appeared to reduce in size after doxycycline treatment, but then grew and turned erythematous. The lesion was surgically excised and was vascular with calcification and cheesy inclusions. The mass was quite close to the skin and the clinical diagnosis at the time of surgery was a pilomatrixoma, which was corroborated on pathological evaluation.

- Citation: Whittemore KR, Cohen M. Imaging and review of a large pre-auricular pilomatrixoma in a child. World J Radiol 2012; 4(5): 228-230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i5/228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i5.228

In 1880, Malherbe et al[1] described calcifying epitheliomas and originally hypothesized that the lesions arose from sebaceous cysts. Forbis et al[2] proposed the term pilomatrixoma, to reflect the more accurate description of a benign ectodermal tumor originating from the germinal matrix center of the hair follicle. These tumors arise most commonly in children and young adults, with approximately 45% arising before 21 years of age in a large review by Yencha, although some studies show a second peak in the elderly[3,4]. More then 50% arise in the head and neck where they are the third most commonly excised superficial lesions, following epidermoid cysts and lymph nodes. Pilomatrixomas also occur in the upper extremity, trunk, and lower extremity and have never been reported on the palms or soles, presumably because they lack hair-bearing skin. The majority of studies demonstrate a female predominance[3,5].

A 10-year-old girl presented with a mildly tender mass in her right preauricular region. She noted swelling when sitting with her head in her hand. The swelling became larger and purple; it was not painful but tender. The mass never drained. She was initially started on cephalexin and then clarithromycin, but no response was noted from either antibiotic. Physical examination revealed the following: there were no craniofacial dysmorphisms, and cranial nerve VII function was normal; her pinnas were normal as were the external auditory canals and tympanic membranes; and a raised purple lesion was palpated with mild erythema anterior to her tragus, which was soft and mildly tender to the touch. The lesion was largest at 2 cm in the anterior-posterior dimension. Lyme titers and a computed tomographic (CT) scan with contrast of the facial region was obtained.

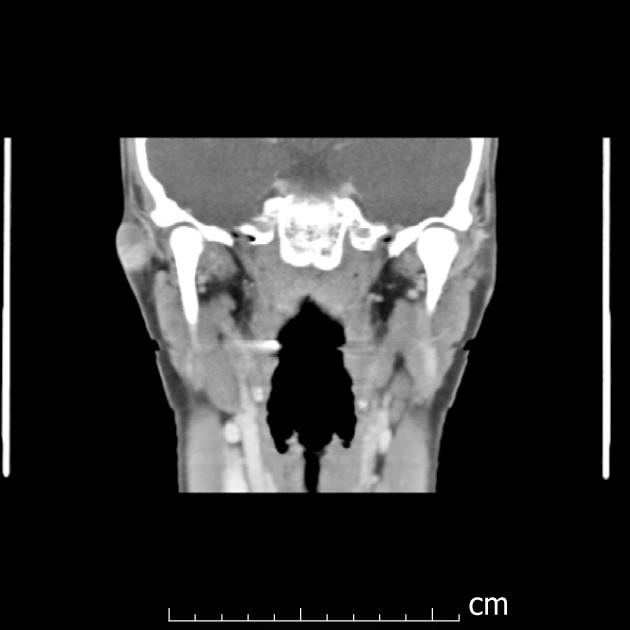

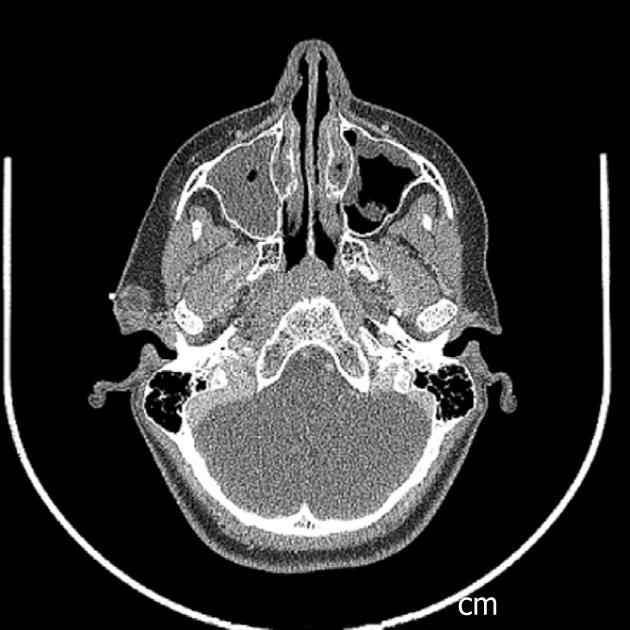

An elevated Lyme titer was found, and the patient was started on doxycycline, after which the lesion decreased. The lesion was no longer purple, just slightly red without drainage. CT results revealed the lesion to be superficial to the parotid gland (Figures 1 and 2). The radiology report noted a 1.5 cm well circumscribed peripherally enhancing and heterogenous lesion in the right pre-auricular superficial soft tissues without surrounding inflammatory changes. This most likely represents a first brachial cleft cyst, possibly with prior superinfection. Differential considerations include a dermoid or less likely an enlarged lymph node. Of note, a PPD was positive and a chest x-ray did not reveal any evidence of mediastinal adenopathy. Doxycycline treatment was completed after 5 wk; 2 wk later, the patient reported the lesion had grown and was itchy and appeared erythematous. The patient was placed on Augmentin, and surgery was scheduled.

A pre-auricular incision was used to approach the mass. It was found to be vascular with calcification and containing cheesy inclusions (Figure 3). It was quite close to the skin and based on these findings the clinical diagnosis was a pilomatrixoma, which was corroborated on pathological evaluation that noted grossly fragments of pink and tan soft tissue and white and tan firm tissue measuring 4.4 cm × 2.5 cm × 0.7 cm in aggregate.

Pilomatrixomas typically present as a firm, slow-growing, painless mass, present for months or years before diagnosis. A bluish hue or telangiectasia overlying the lesion is frequently described. The “tent sign”, described by Graham and Merwin, is noted when the skin is stretched over the tumor and the irregular surface can be palpated[6]. Pilomatrixomas are usually well-circumscribed superficial lesions which may be adherent to the overlying skin but should move freely over the underlying area. However, cystic pilomatrixomas lack the characteristic firmness of the classic lesions. Most masses measure less then 3 cm in diameter[7]. In the head and neck, the neck, cheek, and pre-auricular region are the most common sites[3-5].

Although typically appearing as a solitary mass, multiple lesions are noted in 2%-10% of patients[2,5,8]. Multiple lesions have been described both in isolation or associated with Gardner Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, and sarcoidosis[9-11].

Misdiagnose of pilomatrixoma is a common occurrence despite their frequency, with diagnostic accuracy of pre-operative diagnosis frequently less then 50%. The differential diagnosis of a lesion that may present like a pilomatrixoma is broad, and includes epidermal cysts, dermoid cysts, branchial remnants, atypical mycobacterial infections, parotid lesions, pre-auricular sinuses, ossifying hematoma, giant cell tumor, chondroma and foreign-body reactions[4,5,8].

FNA has been utilized, although without the presence of ghost cells in the aspirate the diagnosis may be difficult. Findings of ghost cells, basaloid cells, or calcium depositions may be diagnostic[8].

The utility of radiologic imaging in pilomatrixoma has been debated, with Agarwal et al[5] claiming it is “of little diagnostic value” given the superficial location. Others have utilized CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in lesions overlying the parotid gland to help distinguish deep limit of the lesion relative to the parotid gland[8]. Plain films may demonstrate calcifications, but are not classically utilized in evaluating head and neck lesions. Authors have described the use of ultrasound instead of CT and MRI, particularly as this can avoid sedation or general anesthesia in young children. Pilomatrixomas typically present as a well-defined, hyperechoic or isoechoic nodule with a hypoechoic rim and posterior shadowing. CT demonstrates a well-defined mass of soft tissue density with mild to moderate enhancement with contrast. In Lim’s review of the radiologic findings in pediatric patients with pilomatrixomas, 81% had evidence of calcific foci within the mass. MRI shows a mass with homogenous, intermediate signal intensity on T1 weighted imaging, and inhomogenous intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images[12].

Grossly, pilomatrixomas appear as well circumscribed firm masses situated superficially, either in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Cut sections often reveal grey, brown, or white material. Histopathologic findings include irregular islands of epithelial cells in a characteristic organization with a biphasic architecture composed of central ghost cells and varying amounts of basaloid cells in the periphery. These are the two major cell types forming pilomatrixomas. First, there are basaloid cells, which have deeply staining basophilic nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and indistinct cell borders. These cells are typically nucleated and arranged along the periphery of the tumor islands. Second, there are keratinized ghost or shadow cells, that show distinct borders and central, unstained areas. These are enucleated and located in the center of the islands. Ghost cells form from basaloid cells that have attempted to produce hair; however, differentiation in pilomatrixomas is towards hair matrix formation, not hair shaft formation. Keratinization of the basaloid cells leads to formation of the ghost cells, with an increase in the ratio of ghost cells to basaloid cells as the neoplasm ages. Foreign body reactions can be seen in areas where there is an abundance of keratinized debris. The presence of ghost cells and basaloid cells, as well as the lobulated pattern, is diagnostic for a pilomatrixoma[2,3,5].

Complete excision is the preferred treatment, as spontaneous regression has not been described. In certain cases, it is necessary to excise the overlying skin to remove tumor adherent to the dermis, but care should be used to preserve the overlying skin. Adherence to deep structures is not noted. The risk of recurrence is as high as 4%, although it is generally accepted that rates of recurrence with complete excision is low[8]. Malignant transformations are rare and are limited to those occurring in middle aged or elderly patients[4].

Pilomatrixomas are generally diagnosed on a clinical basis, but there are characteristic CT and MRI findings. These may aid in pre-operative planning, particularly for noting the depth of the lesion. In this case, CT findings aided during surgery, as a parotidectomy was deemed unnecessary. However, for diagnostic purposes, the differential diagnosis is too broad to make a firm conclusion on radiographic imaging alone. Final diagnosis of a pilomatrixoma will be determined by histopathology.

We would like to thank Jenna Dargie for her great efforts in this manuscript preparation.

| 1. | Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Notes on calcifying epitheliomas of sebaceous glands. Prog Med (Paris). 1880;8:826-837. |

| 2. | Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yencha MW. Head and neck pilomatricoma in the pediatric age group: a retrospective study and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lan MY, Lan MC, Ho CY, Li WY, Lin CZ. Pilomatricoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 179 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1327-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Agarwal RP, Handler SD, Matthews MR, Carpentieri D. Pilomatrixoma of the head and neck in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:510-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kakarala K, Brigger MT, Faquin WC, Hartnick CJ, Cunningham MJ. Cystic pilomatrixoma: a diagnostic challenge. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:830-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Danielson-Cohen A, Lin SJ, Hughes CA, An YH, Maddalozzo J. Head and neck pilomatrixoma in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:1481-1483. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Urvoy M, Legall F, Toulemont PJ, Chevrant-Breton J. [Multiple pilomatricoma. Apropos of a case]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1996;19:464-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McCulloch TA, Singh S, Cotton DW. Pilomatrix carcinoma and multiple pilomatrixomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:368-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harper PS. Calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe. Association with myotonic muscular dystrophy. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:41-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lim HW, Im SA, Lim GY, Park HJ, Lee H, Sung MS, Kang BJ, Kim JY. Pilomatricomas in children: imaging characteristics with pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:549-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Alexander D Rapidis, MD, DDS, PhD, FACS, Professor, Chairman, Department of Head and Neck/Maxillofacial Surgery, Greek Anticancer Institute, Saint Savvas Hospital, 171 Alexandras Avenue, 115 22 Athens, Greece

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM