Revised: December 22, 2010

Accepted: December 29, 2010

Published online: February 28, 2011

Pulmonary hemosiderosis is defined as the clinical and functional consequence of iron overload of the lungs, which usually occurs due to recurrent intra-alveolar bleeding. It can manifest as miliary mottling and should be entertained in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with miliary nodules on chest radiography, especially those with mitral stenosis. The management of secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis secondary to valvular heart disease includes valvuloplasty and/or valve replacement. The radiological opacities may disappear with successful treatment of the underlying valvular disease in many patients. However, they may persist with no physiological impairment to the patient. Here, we present a 32-year-old man with mitral stenosis who presented with fever and miliary shadows on chest radiography, which was ultimately diagnosed as secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis.

- Citation: Agrawal G, Agarwal R, Rohit MK, Mahesh V, Vasishta RK. Miliary nodules due to secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis in rheumatic heart disease. World J Radiol 2011; 3(2): 51-54

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v3/i2/51.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v3.i2.51

Pulmonary hemosiderosis is a rare pulmonary disease that manifests as a triad of hemoptysis, anemia and diffuse parenchymal infiltrates on chest radiography. This condition occurs due to the deposition of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in lungs as a result of repeated alveolar hemorrhage that subsequently leads to the development of pulmonary fibrosis[1]. Hemosiderin is formed by the breakdown of red blood cells and release of iron in heme. It reflects an alveolar abnormality, which may be a primary condition or secondary to a systemic disease. In general, primary pulmonary hemosiderosis is more common than secondary types[2]. The common secondary causes are collagen vascular diseases, coagulation disorders and cardiovascular disorders, especially mitral stenosis[1,3-5].

Mitral stenosis typically results from rheumatic heart disease, although it may be congenital. The increased left ventricular filling pressure in mitral stenosis leads to pulmonary venous hypertension, and, eventually, post-capillary pulmonary arterial hypertension. Recurrent bleeding from the anastomoses between pulmonary arterioles and bronchial vessels results in pulmonary hemosiderosis. Radiologically, hemosiderosis may present as diffuse reticular or miliary nodular opacities, and is seen in 10%-25% of patients with mitral stenosis[6]. Diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage and lung biopsy. This condition is also called “brown lung induration” and is characterized histologically by alveolar hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the alveoli and, to a lesser extent in the interstitium, and mild interstitial thickening that can become prominent in long-standing cases, leading to septal fibrosis[7]. Here, we present the case of a 32-year-old patient who presented with miliary opacities and was ultimately diagnosed with pulmonary hemosiderosis secondary to mitral stenosis. Being a high-prevalence country for tuberculosis (TB), a diagnosis of miliary TB was initially considered in the differential diagnosis of this patient.

A 32-year-old man was admitted with complaints of fever, dry cough and worsening breathlessness of 3 d duration. There was no history of chest pain, hemoptysis or leg edema. In the past, there was a history of fever and joint pains at the age of 5 years, for which he was admitted to hospital, and since then, the patient has been receiving injections of benzathine penicillin every 3 wk. The patient also had a history of progressive dyspnea on exertion over the past 12 years, and before this current hospitalization, his dyspnea was severe enough to limit his daily activities. There was no previous history of cough, chest pain or hemoptysis. For the present illness, he first visited his general practitioner who performed a chest radiograph (Figure 1), which revealed cardiomegaly with straightening of the left heart border, and diffusely distributed miliary (approximately 3 mm) nodular opacities. The patient was subsequently referred to this institute for work-up of fever and the radiological opacities.

Upon examination, the patient was conscious and afebrile with a pulse rate of 96 beats/min, blood pressure of 130/70 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Jugular venous pulse showed prominent a waves; examination of the cardiovascular system showed the apex to be located at the sixth intercostal space in the anterior axillary line, and a palpable diastolic thrill. Auscultation revealed a loud first heart sound, a loud pulmonic component of the second heart sound, and a mid-diastolic murmur with a presystolic accentuation. Examination of the respiratory system was normal. There were no joint deformities or joint tenderness. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

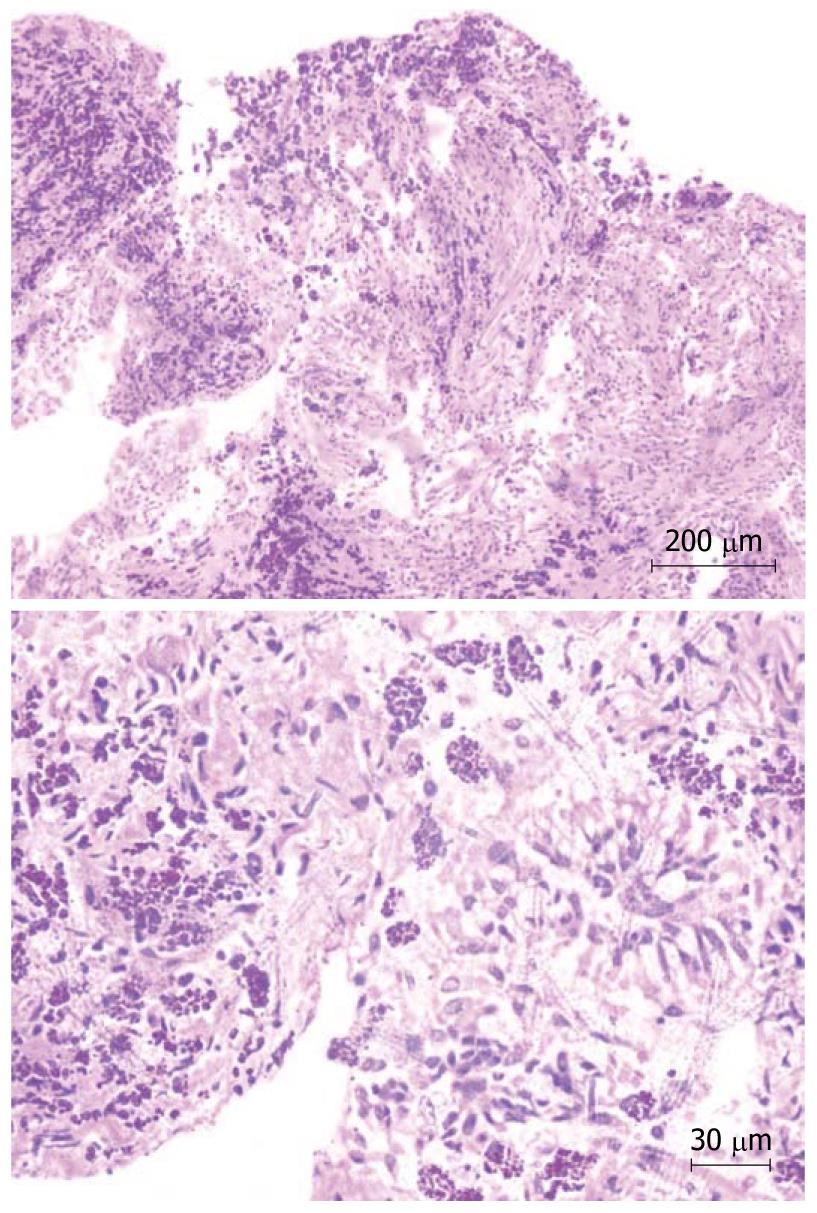

Complete blood count revealed hemoglobin of 102 g/L, total leukocyte count of 10 800/μL and platelet count of 206 000/μL. Peripheral blood film showed microcytosis and hypochromia. The coagulation profile, serum electrolytes, and renal and liver function tests were normal. Routine urine examination was normal. Electrocardiography revealed right axis deviation, P-pulmonale and voltage criteria for right and left ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography was performed, which showed evidence of severe mitral stenosis (mitral valve area: 0.7 cm2), moderate aortic regurgitation with associated pulmonary hypertension, and mild tricuspid regurgitation. Blood cultures and urine cultures were sterile. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed an enlarged pulmonary artery (Figure 2), and the corresponding lung windows showed randomly scattered nodular opacities 2-3 mm in size (Figure 3). Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was done subsequently, and transbronchial lung biopsies were performed, which showed characteristic histological findings of numerous hemosiderin-laden macrophages within the alveolar spaces (Figure 4). A final diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease with severe mitral stenosis with moderate aortic regurgitation with secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis was made. The patient was managed conservatively and his fever remitted with oral paracetamol. A balloon mitral valvuloplasty was done, following which, dyspnea improved and the mitral valve surface area increased to 1.3 cm2. The cause of the radiological abnormalities was explained to the patient, and he was advised to undergo dual valve replacement.

The term hemosiderosis is derived from the Greek words, hemo (blood) and sideros (iron), and is characterized by the focal or generalized accumulation of iron in the form of hemosiderin[3]. Hemosiderin is an intracellular storage form of iron (> 33% iron by weight) and contains ferric hydroxides, polysaccharides, and proteins. The main source of iron in the lungs is from the red blood cells and is metabolized during episodes of alveolar hemorrhage. After 48-72 h of acute bleeding, the alveolar macrophages convert hemoglobin iron into hemosiderin, hence the term hemosiderosis.

Pulmonary hemosiderosis is the clinical and functional consequence of iron overload of the lungs. The deposition of hemosiderin in the lung was first commented upon by Virchow in 1858, but it was in 1928 that Rosenhagen described the occurrence of pulmonary hemosiderosis in association with valvular heart disease[8]. The term pulmonary hemosiderosis is reserved for recurrent intra-alveolar bleeding because hemosiderin-laden macrophages reside for up to 4-8 wk in the lungs. Pulmonary hemosiderosis is considered idiopathic (also known as Ceelen-Gellerstedt’s syndrome) if no other cause is identified, and if the lung biopsy excludes capillaritis, granulomas, or other immune depositions. It can also occur due to various other causes of recurrent alveolar hemorrhage, including mitral stenosis[2]. The diagnosis is often missed because the bleeding can be covert, and hemoptysis is often missing, as in the present case[1].

Mitral stenosis is characterized by left atrial outflow obstruction with resultant pulmonary venous and capillary hypertension, and finally, frank pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulmonary hemosiderosis has been reported to occur in up to 16% of patients with mitral stenosis[1]. The deposition of hemosiderin results from pulmonary capillary hypertension, which results in the formation of anastomoses between pulmonary arterioles and bronchial vessels; these varicose anastomoses repeatedly rupture with resultant recurrent intra-alveolar hemorrhages and formation of pulmonary hemosiderin[5]. The clinical presentation of focal pulmonary hemosiderosis is probably more common than the presentation of miliary opacities on chest radiography, as seen in the present case, which are quite often mistaken for other conditions[9]. Other factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hemosiderosis resulting from mitral stenosis, because hemoptysis and pulmonary capillary hypertension is common, but diffuse pulmonary hemosiderosis is uncommon[4]. However, one caveat is that diffusely scattered hemosiderin collections of < 1 mm do not cast an appreciable shadow on chest radiography, and therefore, pulmonary hemosiderosis can be missed. Chest CT is more sensitive than radiography for detection of small nodular opacities, which has a wide range of differential diagnosis (Table 1).

| Infections | Miliary tuberculosis |

| Fungal infections: histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, | |

| Varicella pneumonia | |

| Pneumoconiosis | Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, silicosis, berylliosis |

| Inflammatory | Sarcoidosis |

| Malignancy | Metastasis (thyroid carcinoma, osteosarcoma) |

| Others | Alveolar microlithiasis, amyloidosis |

Iron exerts a toxic effect, partially through its capacity to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals from less toxic oxygen superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions), which in turn, cause lipid layer peroxidation, protein and carbohydrate degradation, and subsequent fibrogenesis[3]. Within the pulmonary macrophages, iron is removed from hemoglobin by the enzyme heme oxygenase, however, the capacity of alveolar macrophages to metabolize iron is easily exhaustible, and the presence of free iron in the alveoli can cause local injury and fibrosis.

Management of secondary pulmonary hemosiderosis secondary to valvular heart disease includes valvuloplasty and/or valve replacement. There are cases on record where there is gradual clearance of the pulmonary opacities after treatment of mitral stenosis[1]. On the other hand, there are cases where there is little fibrotic reaction in spite of radiological (as in our patient) and autopsy evidence of heavy pulmonary hemosiderosis[1,6-8,10].

In conclusion, pulmonary hemosiderosis secondary to mitral stenosis can present as miliary nodules on chest radiography, and this fact should be kept in mind when managing such patients. Although in many cases the radiological opacities may disappear with successful treatment of the underlying valvular disease, in others, the radiological opacities may persist with no physiological impairment to the patient.

| 1. | Datey KK, Kelkar PN. Pulmonary haemosiderosis in mitral stenosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 1970;18:647-651. |

| 2. | Ioachimescu OC, Sieber S, Kotch A. Idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis revisited. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:162-170. |

| 3. | Ioachimescu OC, Farver C, Stoller JK. Hemoptysis in a 77-year-old male with a systolic murmur. Chest. 2005;128:1022-1027. |

| 4. | Lendrum AC. Pulmonary haemosiderosis of cardiac origin. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1950;62:555-561. |

| 5. | Taylor HE, Strong GF. Pulmonary hemosiderosis in mitral stenosis. Ann Intern Med. 1955;42:26-35. |

| 6. | Chamusco RF, Heppner BT, Newcomb EW 3rd, Sanders AC. Mitral stenosis: an unusual association with pulmonary hemosiderosis and iron deficiency anemia. Mil Med. 1988;153:287-289. |

| 7. | Ellman P. Pulmonary haemosiderosis. Clinical and radiological aspects. Proc R Soc Med. 1960;53:333-338. |

| 8. | Ellman P, Oliver RA. Association of cardiac pulmonary haemosiderosis and fibrosis. Br Med J. 1959;2:988-990. |

| 9. | Malhotra P, Aggarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK, Awasthi A, Radotra BD. Coeliac disease as a cause of unusually severe anaemia in a young man with idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis. Respir Med. 2005;99:451-453. |

Peer reviewers: Edson Marchiori, MD, PhD, Full Professor of Radiology, Department of Radiology, Fluminense Federal University, Rua Thomaz Cameron, 438, Valparaiso, CEP 25685, 120, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Edwin JR van Beek, MD, PhD, Med, FRCR, SINAPSE, Chair of Clinical Radiology, CO.19, Clinical Research Imaging Centre, Queen's Medical Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, 47 Little France Crescent, Edinburgh EH16 4TJ, United Kingdom

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM