Published online Aug 28, 2010. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i8.329

Revised: June 29, 2010

Accepted: July 6, 2010

Published online: August 28, 2010

In this report, we present a case of advanced squamous cell cancer located in the rectum of a 78-year-old woman treated with chemoradiation with curative intent. The patient showed a complete clinical response to chemoradiation; multiple biopsies were performed at the site of the previous mass 5 mo after the end of treatment and histological examination showed no residual tumour in the specimens. Surgical intervention was avoided and the patient was free of disease 12 mo after the diagnosis of cancer. Primary chemoradiation should be considered as the treatment of choice for this rare malignancy.

- Citation: Iannacone E, Dionisi F, Musio D, Caiazzo R, Raffetto N, Banelli E. Chemoradiation as definitive treatment for primary squamous cell cancer of the rectum. World J Radiol 2010; 2(8): 329-333

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v2/i8/329.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v2.i8.329

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer in the Western world[1]. Adenocarcinoma represents more than 90% of all colorectal cancers while other histological subtypes, such as squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), adenosquamous, carcinoid or lymphoid, are identified only occasionally. SCC of the rectum is an extremely rare malignancy with an incidence of less than 1/10 000 of all colorectal cancers[2]. It was described for the first time by Raiford[3] in 1933.

Diagnosis of a primary SCC of the rectum is neither immediate nor simple. According to Williams et al[4], the following criteria must be satisfied: (1) absence of metastases from other sites (such as SCC of the lung); (2) absence of fistulas between the rectum and adjacent affected organs, which could be the source of SCCs; and (3) absence of a SCC of the anus with cranial extension into the lower rectum.

The natural history and therapeutic options for such a rare tumour have not yet been clearly defined. Surgery is still considered the gold standard of treatment, however, several authors consider the association of radiotherapy and chemotherapy as an effective alternative to resection[5]. The scientific literature on SCC consists mainly of case reports. Since 1933, only 73 cases of SCC have been reported, with the largest series on 12 patients being reported by Nahas et al[6]. In this paper, we present a case of primary SCC of the rectum treated with chemoradiation alone with curative intent.

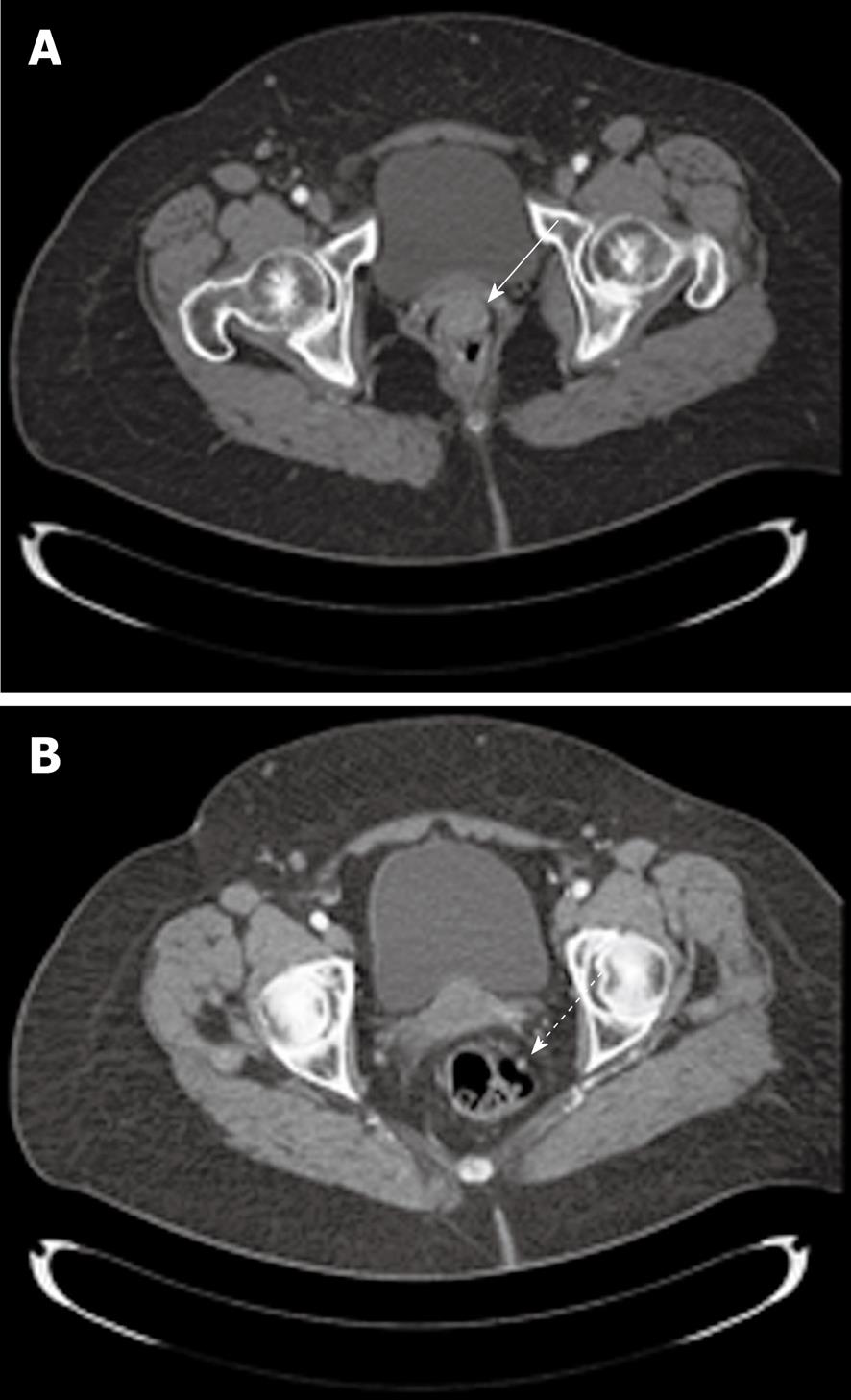

In May 2009 an obese, non-smoking, 78-year-old woman, with an ECOG performance status of 1, was referred to the Department of Radiotherapy, University “Sapienza” for a neoplasm located in the rectum. The first symptom of the disease was rectal bleeding and, therefore, the patient underwent digital rectal examination (DRE), which revealed the presence of a round and irregular mass located in the anterior rectal wall. Subsequently, a colonoscopy was performed. The exam registered a round and hard consistent mass protruding into the lumen, located entirely in the lower rectum at a distance of 5 cm from the anal verge. Histological examination of the specimen revealed a SCC of the large intestine. A total body computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which confirmed the presence of a round neoplasm with irregular margins of 30 mm × 20 mm × 21 mm (Figure 1A). The cranial limit of the mass was located approximately 25 mm from the anorectal junction along the anterior rectal wall. A small lymph node was visible in the mesorectum 2 cm above the lesion (Figure 1B). The perirectal fat was not involved and neither were the elevator muscles of the anus.

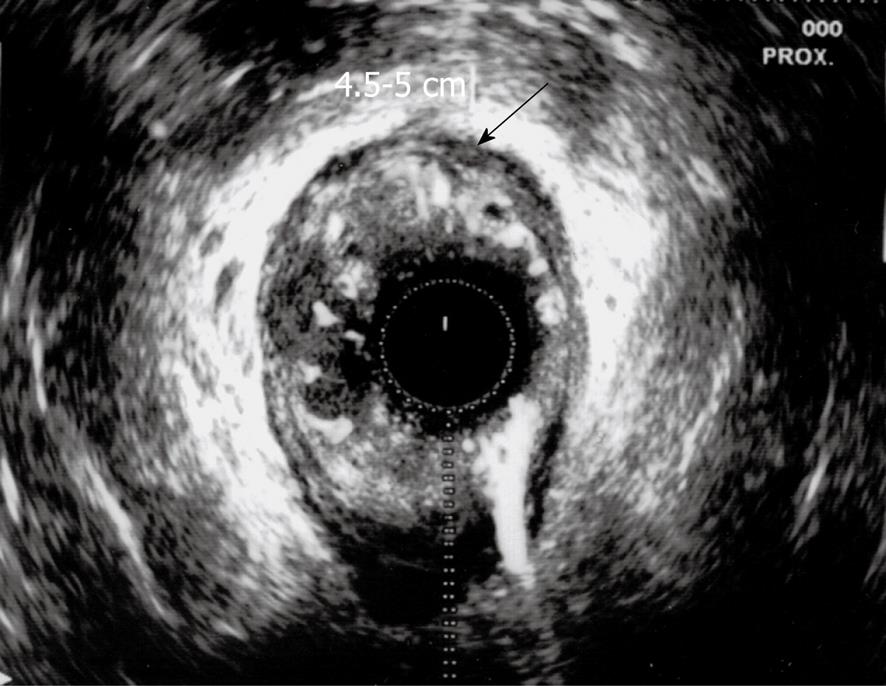

The presence of metastatic disease was excluded. The therapeutic strategy for such a case was discussed with our surgery team. Operative risk was considered high due to the patient’s age and comorbidities, and surgery was excluded. The patient was referred for chemoradiation as a curative treatment. An endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) was also performed, which confirmed localization of the lesion in the anterior wall of the rectum with no extension in the anal canal (Figure 2). The exam revealed the presence of 2 round, 8 mm diameter, possibly involved lymph nodes located in the mesorectum 8 cm and 7 cm from the anal margin.

Given the squamous nature of the neoplasm and the choice of treatment, the disease was staged as clinical T2N1M0 (stage IIIA) according to the TNM classification system for squamous cell cancer of the anus (AJCC Sixth Edition).

Chemotherapy: A medical and physical exam, with complete laboratory tests, was performed before each cycle of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy consisted of continuous infusion of 5-FU 750 mg/mq die, days 1-4 and days 36-40, plus 10 mg/mq mitomycin days 1 and 36.

Radiotherapy: Radiotherapy was delivered using a linear accelerator with energy of 6-15 MV using a 3D conformal technique. The planning target volume 2 (PTV2) included the site of disease and pelvic nodal stations (internal iliac, external iliac, obturator, mesorectal, presacral and inguinal nodes).

The PTV1 encompassed the site of disease with an isotropic margin of 2 cm. The PTV2 received 45 Gy in 25 daily fractions of 1.8 Gy each. PTV1 was boosted to 59.4 Gy with the addition of 8 fractions using a multiple field technique. Toxicity was graded according the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0[7].

There was no haematological toxicity; gastrointestinal and skin toxicity adverse events were ≤ G2. As expected, skin toxicity, grade 2, occurred bilaterally in the inguinal area and was controlled with proper topical treatment.

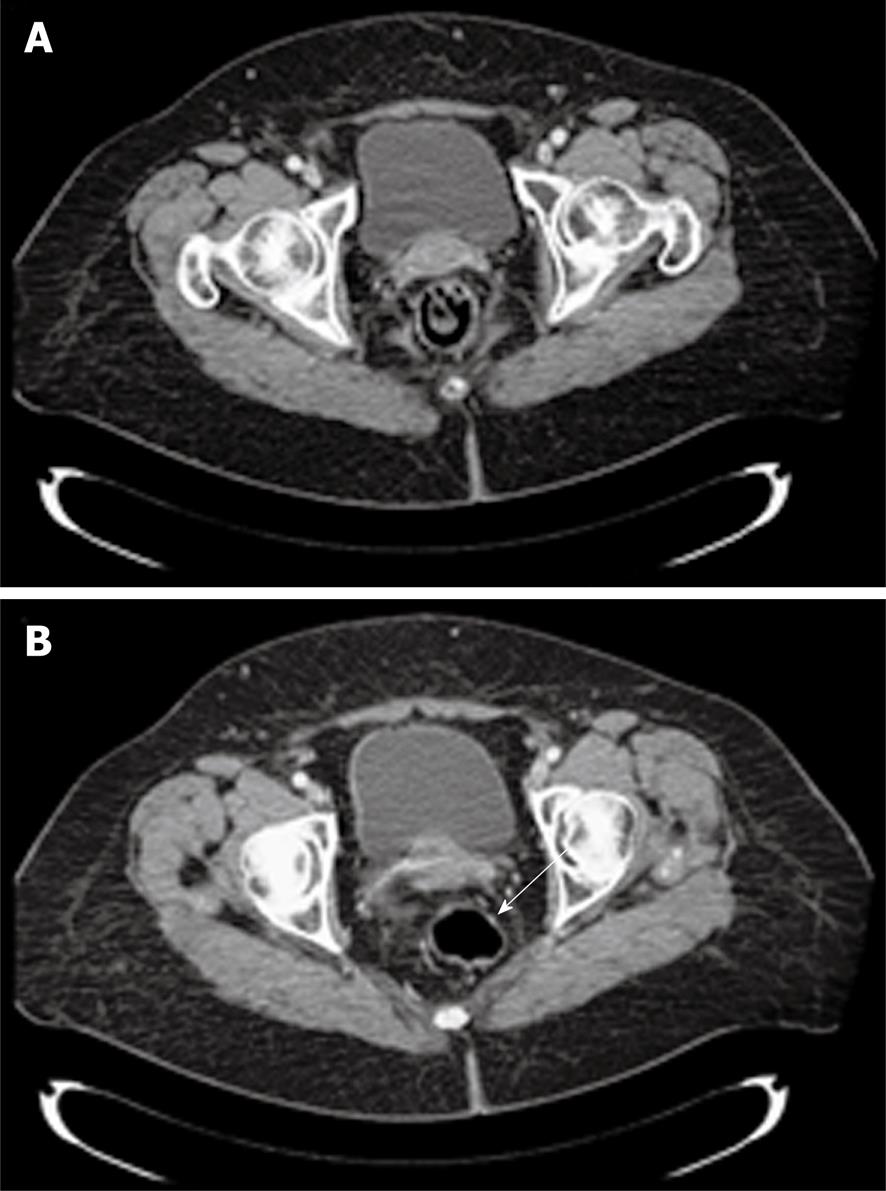

The patient was revaluated 7 wk after the end of chemoradiation by DRE and ERUS. The anterior wall of the rectum appeared at DRE to be completely smooth with difficult identification of the treated lesion. Transanal ultrasound registered the presence of a hypoechoic scar located anteriorly in the rectum with a craniocaudal extension of 1 cm. A total body CT scan was performed 10 wk after the end of treatment. The lesion appeared greatly reduced in size and identifiable with difficulty, as was the small lymph node detected at the first CT scan (Figure 3).

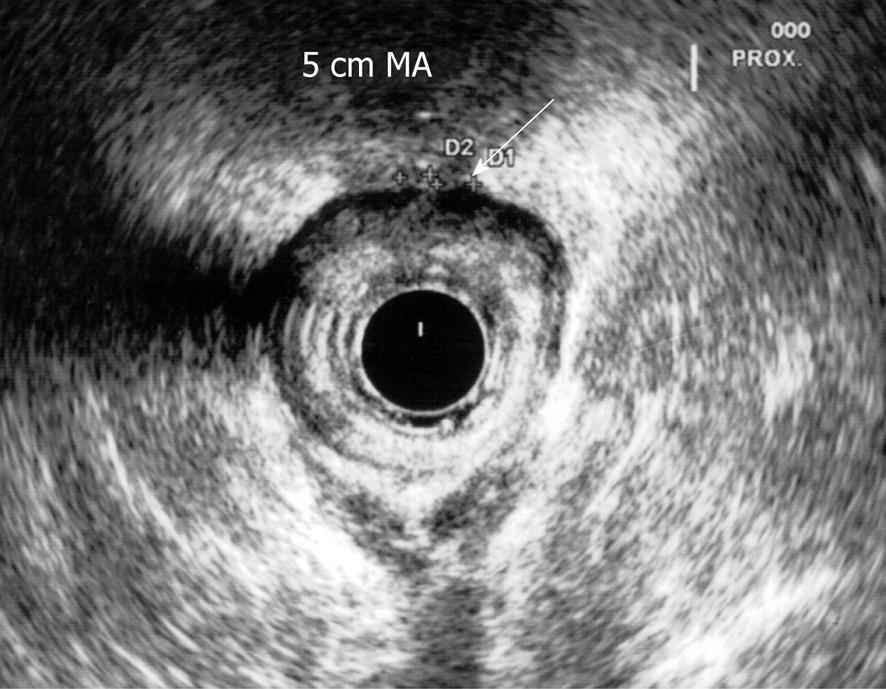

Three months after the end of chemoradiation, a new ultrasound examination confirmed the reduction of the lesion with no pathological nodes identified in the mesorectum (Figure 4). Given the initial desirable clinical outcome, a proctoscopy with possible biopsy was scheduled 4 mo after the end of treatment. Meanwhile, the patient underwent anal brushing to search for sequences of papillomavirus by means of PCR. The sample was negative for the presence of HPV6, HPV11, HPV16 and HPV18.

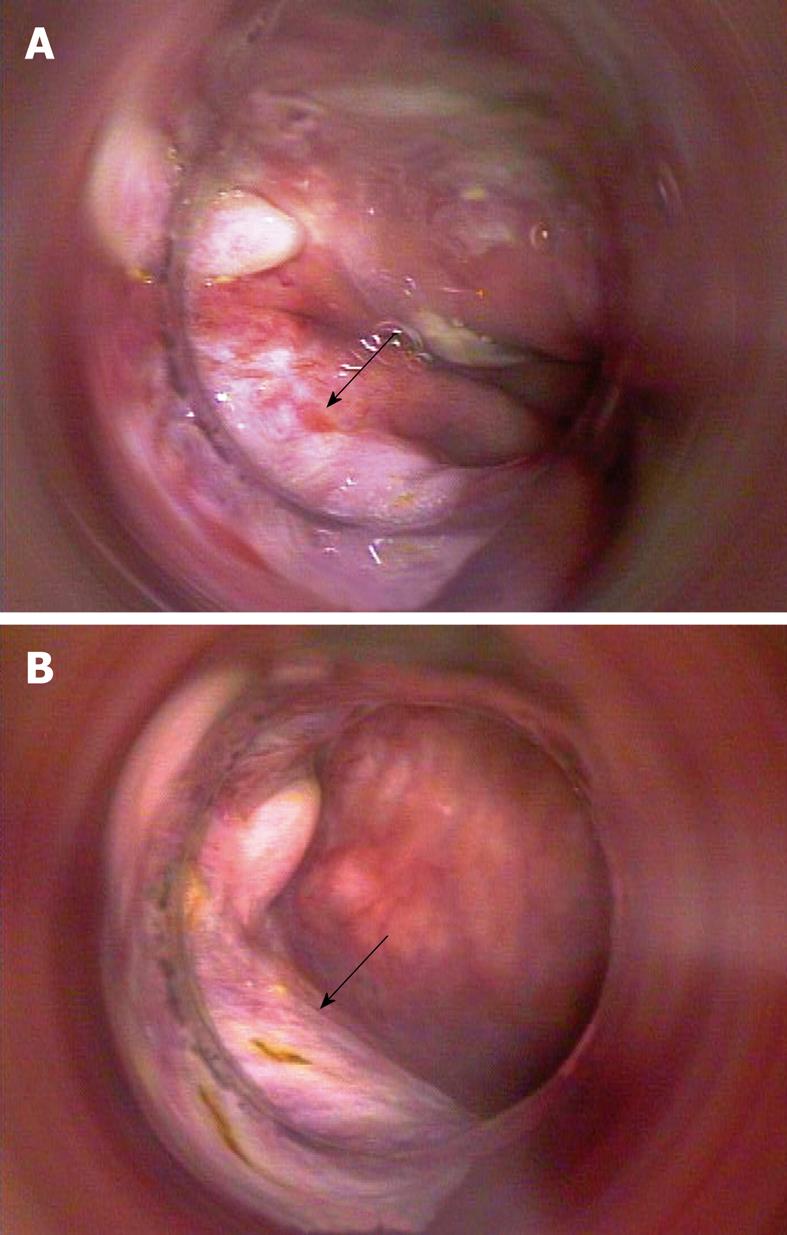

In December 2009, the patient underwent a first proctoscopy, which showed no lesions protruding into the intestinal lumen, but showed only the presence of a plain-white area at the site of the previous injury and no biopsies were performed (Figure 5A and B). One month later (5 mo after the end of treatment) a proctoscopy was executed and multiple biopsies were performed up to 8 cm from the anal margin. No residual cancer cells were found at the histological examination of specimens. A total body CT scan was also performed, which confirmed that the patient was free of disease 12 mo after the diagnosis of cancer.

Squamous cell cancer of the rectum is an extremely rare malignancy. It represents 0.1%-0.2% of all colorectal cancers. It seems to occur more frequently in women[8]. The review of Frizelle et al[9], conducted at the Mayo Clinic on all cases of adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum from 1907 to 1992, identified only 11 cases of pure SCC.

The etiology of SCC of the rectum is uncertain. Briefly, several theories have been proposed: (1) proliferation of stem cells capable of multidirectional differentiation[10]; (2) differentiation of basal undifferentiated cells in squamous cells with subsequent malignant transformation[11]; (3) chronic irritation caused by conditions such as ulcerative colitis[12], radiation exposure[13], and HPV infection that can result in squamous metaplasia and subsequent tumor development; and (4) squamous differentiation of adenoma and adenocarcinoma[14]. Given the extreme rarity of this cancer, its natural history is not well known. Consequently, therapeutic strategy cannot be easily standardized. Traditionally, surgery is considered the most appropriate curative treatment. The surgical procedure depends on localization of the tumour mass and on TNM classification of the disease. In the case of advanced tumour, a conservative approach is not recommended. Total mesorectal excision, performed by anterior resection of the rectum or by abdominoperineal amputation with a definitive stoma, must be considered the preferred surgical option. Each type of surgery, however, is associated with a significant risk of morbidity (13%-46%) and mortality (1%-7%)[15].

Several authors suggested that chemoradiation could play a role in the treatment of squamous cell cancer of the rectum. Some researchers[16] investigated the effectiveness of chemoradiation as a postoperative treatment of this type of tumour, reporting a low profile of toxicity. Multimodal treatment did not show any advantage in terms of overall survival compared to surgery alone.

Other authors went even further, reporting their experience with chemoradiation as a definitive treatment for squamous cell cancer of the rectum. The series of Clark et al[17] included 7 patients treated by primary chemoradiation. Radiotherapy was administered at a dose of 30.6 Gy delivered to the primary tumour and the regional nodes. The tumour mass with a 2 cm margin was boosted to a total dose of a 50.4 Gy. The multimodal treatment was feasible; only one patient experienced severe anal soreness and had a 7 d break in the radiotherapy treatment.

Results of treatment were excellent; all patients but one showed a complete clinical response to chemoradiation. This patient, with a partial radiological response to treatment, decided to undergo surgery and no residual tumour was found at histological examination of the surgical specimen.

These findings demonstrate that definitive chemoradiation should be considered as a feasible and effective alternative to surgery. Acute toxicity of chemoradiation is low and long term toxicity, with symptomatic rectal stricture due to the non operative approach, is possible but its incidence is rarely reported in the literature[18]. A prospective comparison between the two therapeutic options is impossible, due to the rarity of this tumour. Nevertheless, some considerations are offered. First of all, the historical standard treatment for SCC of the anus was demolitive surgery by means of abdominoperineal amputation (Miles’ intervention). It was only after the revolutionary work of Nigro[19], dated 1974, when chemoradiation was shown as effective as a primary treatment of epidermoid anal cancer. Currently, the latest update of the results of the ACT I trial[20], which compared chemoradiation to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of squamous anal cancer, showed that the superiority of chemoradiation is present even 12 years after treatment, confirming the association of radiotherapy and chemotherapy as the gold standard for anal cancer treatment.

In the case of rectal cancer, a different therapeutic strategy is required. Adenocarcinoma represents more than 90% of all rectal tumors and surgery, i.e. total mesorectal excision[21], must be considered as the milestone of a multimodal treatment, including radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation has been demonstrated to reduce the rate of local recurrence compared to postoperative chemoradiation[22] The use of standard, 5-FU based preoperative chemoradiation in the case of adenocarcinoma of the rectum leads to a percentage of pathological complete response (pCR), which varies from 5% to 16%[23] in randomized phase III studies. Several phase II studies of intensified neoadjuvant treatment reported rates of pCR up to 30%[24]. The work of Habr-Gama et al[25] represents the first, successful, non operative approach to rectal cancer. This paper reported similar curves of survival between patients who avoided surgery and showed a clinical complete response, and operated patients registering a pathological complete response at histological examination.

In summary, non operative management represents the standard approach for anal cancer. In the case of squamous cell cancer of the rectum, a complete response to chemoradiation can be expected in the majority of patients, and surgery should be reserved for cases of treatment failure. The assessment of response to conservative therapy should be done 4-6 mo after the end of chemoradiation treatment.

In our paper, we described the case of a 78-year-old woman affected by squamous cell cancer of the rectum, successfully managed by chemoradiation as a definitive treatment. Chemoradiation was feasible, with a low profile of toxicity. It must be noted that, unlike other reports, in our case, radiotherapy was delivered with the use of 3D conformal technique, which permitted delivering high doses of radiation both to PTV2 and PTV1 (45 and 59.4 Gy, respectively) without exceeding nearby normal tissue tolerance. A further evolution of radiotherapy could be represented by the use of more sophisticated techniques, such as helical tomotherapy and intensity modulated radiation therapy, whose first experiences in the treatment of anal cancer were extremely promising in terms of local control and toxicity[26,27]. Squamous rectal cancer could also benefit from new radiotherapy techniques associated with well established protocols of chemotherapy, with the goal of making chemoradiation with radical intent the treatment of choice for this rare malignancy.

| 1. | Dyson T, Draganov PV. Squamous cell cancer of the rectum. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4380-4386. |

| 2. | Anagnostopoulos G, Sakorafas GH, Kostopoulos P, Grigoriadis K, Pavlakis G, Margantinis G, Vugiouklakis D, Arvanitidis D. Squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14:70-74. |

| 3. | Raiford TS. Epitheliomata of the lower rectum and anus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:21-35. |

| 4. | Williams GT, Blackshaw AJ, Morson BC. Squamous carcinoma of the colorectum and its genesis. J Pathol. 1979;129:139-147. |

| 5. | Rasheed S, Yap T, Zia A, McDonald PJ, Glynne-Jones R. Chemo-radiotherapy: an alternative to surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum--report of six patients and literature review. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:191-197. |

| 6. | Nahas CS, Shia J, Joseph R, Schrag D, Minsky BD, Weiser MR, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Klimstra DS, Tang LH. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the rectum: a rare but curable tumor. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1393-1400. |

| 7. | Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3. 0, Publish Date: August 9, 2006. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov. |

| 8. | Lafreniere R, Ketcham AS. Primary squamous carcinoma of the rectum. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:967-972. |

| 9. | Frizelle FA, Hobday KS, Batts KP, Nelson H. Adenosquamous and squamous carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum: a clinical and histopathologic study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:341-346. |

| 10. | Ouban A, Nawab RA, Coppola D. Diagnostic and pathogenetic implications of colorectal carcinomas with multidirectional differentiation: a report of 4 cases. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2002;1:243-248. |

| 11. | Michelassi F, Mishlove LA, Stipa F, Block GE. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the colon. Experience at the University of Chicago, review of the literature, report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:228-235. |

| 12. | Michelassi F, Montag AG, Block GE. Adenosquamous-cell carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:323-326. |

| 13. | Yurdakul G, de Reijke TM, Blank LE, Rauws EA. Rectal squamous cell carcinoma 11 years after brachytherapy for carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 2003;169:280. |

| 14. | Audeau A, Han HW, Johnston MJ, Whitehead MW, Frizelle FA. Does human papilloma virus have a role in squamous cell carcinoma of the colon and upper rectum? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:657-660. |

| 15. | Martling AL, Holm T, Rutqvist LE, Moran BJ, Heald RJ, Cedemark B. Effect of a surgical training programme on outcome of rectal cancer in the County of Stockholm. Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group, Basingstoke Bowel Cancer Research Project. Lancet. 2000;356:93-96. |

| 16. | Schneider TA 2nd, Birkett DH, Vernava AM 3rd. Primary adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:144-147. |

| 17. | Clark J, Cleator S, Goldin R, Lowdell C, Darzi A, Ziprin P. Treatment of primary rectal squamous cell carcinoma by primary chemoradiotherapy: should surgery still be considered a standard of care? Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2340-2343. |

| 18. | Brammer RD, Taniere P, Radley S. Metachronous squamous-cell carcinoma of the colon and treatment of rectal squamous carcinoma with chemoradiotherapy. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:219-220. |

| 19. | Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B Jr. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:354-356. |

| 20. | Northover J, Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, James R, Meadows H, Wan S, Jitlal M, Ledermann J. Chemoradiation for the treatment of epidermoid anal cancer: 13-year follow-up of the first randomised UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial (ACT I). Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1123-1128. |

| 21. | Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479-1482. |

| 22. | Glynne-Jones R, Mawdsley S, Pearce T, Buyse M. Alternative clinical end points in rectal cancer--are we getting closer? Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1239-1248. |

| 23. | Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, Martus P, Tschmelitsch J, Hager E, Hess CF. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731-1740. |

| 24. | Gambacorta MA, Valentini V, Coco C, Morganti AG, Smaniotto D, Miccichè F, Mantini G, Barbaro B, Garcia-Vargas JE, Magistrelli P. Chemoradiation with raltitrexed and oxaliplatin in preoperative treatment of stage II-III resectable rectal cancer: Phase I and II studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:139-148. |

| 25. | Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, Sabbaga J, Ribeiro U Jr, Silva e Sousa AH Jr, Campos FG, Kiss DR, Gama-Rodrigues J. perative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2004;240:711-717. |

| 26. | Pepek JM, Willett CG, Wu QJ, Yoo S, Clough RW, Czito BG. Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy for Anal Malignancies: A Preliminary Toxicity and Disease Outcomes Analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;Epub ahead of print. |

| 27. | Joseph KJ, Syme A, Small C, Warkentin H, Quon H, Ghosh S, Field C, Pervez N, Tankel K, Patel S. A treatment planning study comparing helical tomotherapy with intensity-modulated radiotherapy for the treatment of anal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94:60-66. |

Peer reviewers: Thomas J George, Jr., MD, FACP, Assistant Professor, Director, GI Oncology Program, Associate Director, HemOnc Fellowship Program, University of Florida, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 1600 SW Archer Road, PO Box 100277, Gainesville, FL 32610, United States; Heriberto Medina-Franco, MD, National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition “Salvador Zubiran”, Vasco de Quiroga 15 Colonia Seccion XVI, Mexico City ZIP 14000, Mexico

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Zheng XM