Published online Jul 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i7.110385

Revised: June 19, 2025

Accepted: July 14, 2025

Published online: July 28, 2025

Processing time: 50 Days and 10.9 Hours

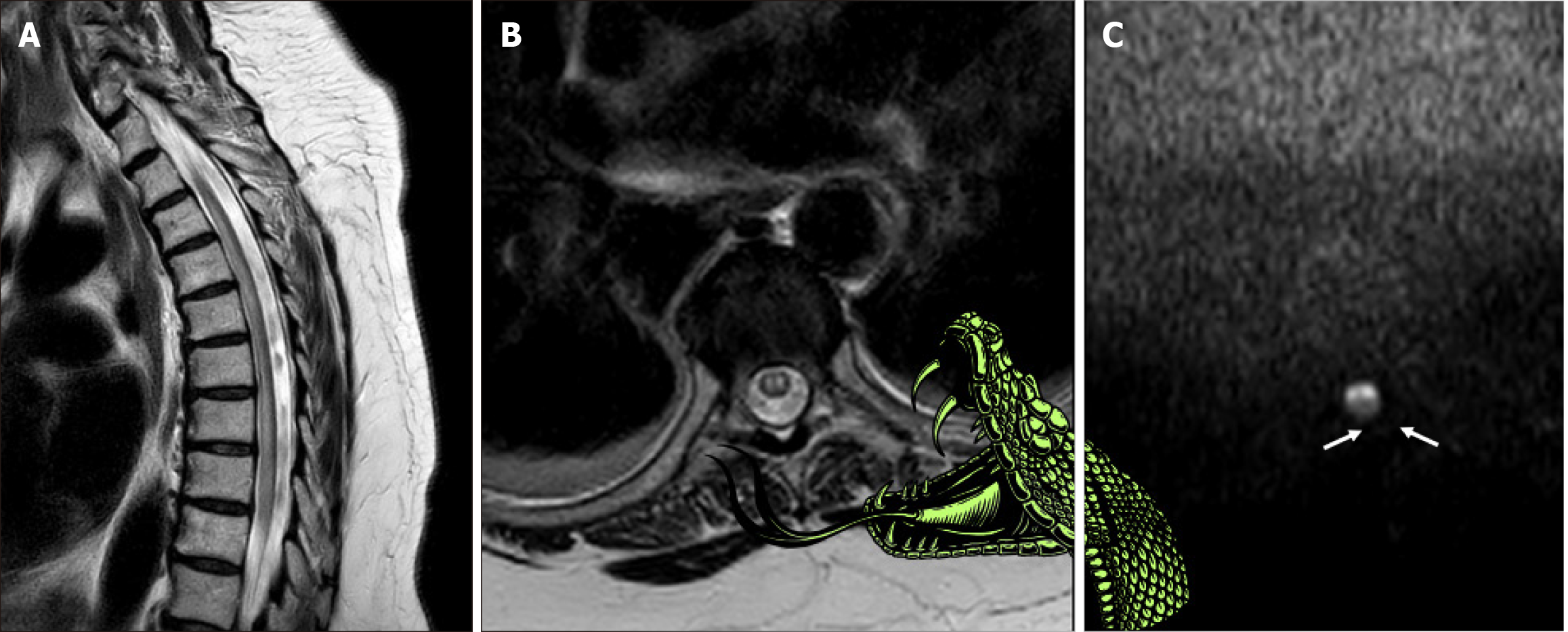

Descriptive signs in radiology can aid in easier pattern recognition and quicker diagnosis. In spinal cord ischemia, paired anterior-horn T2-hyperintensities have traditionally been known as the “owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign. We discuss how these signs, while visually apt, convey no pathophysiologic context and propose renaming this finding the “snake bite sign”. The image still evokes two punctate marks, yet the metaphor extends to a snake bite (two fang-like dots) rather than two bright foci (eyes) staring back at the viewer. Moreover, besides the sign metaphorically resembling a traumatic puncture of the two fangs, on the occasion of a venomous snake bite occurring elsewhere, additional neurological consequences may occur, paralleling the neurological deficits seen in anterior spinal artery infarction and several mimicking myelopathies, thus further high

Core Tip: We propose renaming the “owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign seen in spinal cord pathologies such as ischemia to the “snake bite sign”. This term retains the visual metaphor while adding clinical relevance, as it mirrors both the appearance (two fang-like dots) and neurological consequences of an elsewhere occurring venomous snake bite. It enhances educational impact and diagnostic clarity in spinal cord pathology, especially anterior spinal artery infarction when symmetrical anterior-horn hyperintensities appear.

- Citation: Arkoudis NA, Karachaliou A, Triantafyllou G, Papadopoulos A, Koutserimpas C, Velonakis G. Spinal cord ischemia: The “snake bite sign”. World J Radiol 2025; 17(7): 110385

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i7/110385.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i7.110385

Descriptive imaging signs in radiology increase educational impact by enabling quick and accurate recollection and identification of critical radiologic findings[1]. In spinal cord pathology, such as ischemia, symmetrical ovoid or circular high signal intensity lesions depicted on T2 axial images have been metaphorically described in the literature as “owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign, as they evoke the image of two bright foci staring back at the viewer[2-5].

Zhang et al[6] previously reported a rare spontaneous infarction of the conus medullaris in a 79-year-old man, highlighting a paired anterior-horn hyperintensity on axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging which they also label in their manuscript as the “snake-eye appearance”, otherwise known as “owl-eye appearance”. In addition, in their review of 23 prior conus infarctions, only two cases displayed the typical “snake-eye appearance”, therefore emphasizing its diagnostic specificity. Notably, these signs can also be encountered in various other neurological conditions (i.e., chronic compressive myelopathy, Hirayama disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal muscular atrophy syndrome, etc.)[7-10]. In Zhang et al’s Table 2[6], titled “Identification of common diseases related to snake eye sign” a summary of mimicking conditions is displayed. The authors describe how the paired foci are attributed to ischemic necrosis of anterior-horn cells in the anterior-spinal-artery watershed and stress that acute low-back or bilateral leg pain plus this magnetic resonance imaging pattern should raise suspicion of anterior spinal artery ischemia and urgent treatment. Their conclusion repeats that a “snake-eye appearance” on acute imaging is a pivotal early clue to infarction.

Importantly, although these terms (“owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign) have apparently been chosen truthfully in the literature, based on their visual resemblance, they seem to lack an inherent clinical correlation. Therefore, we suggest the adoption of an alternate term, the “snake bite sign” to describe this imaging finding, arguing it provides both visual and clinical relevance. The “snake bite” analogy appropriately characterizes the paired, punctate lesions seen in spinal cord pathology, such as ischemia, closely resembling puncture wounds from a snake’s fangs, as illustrated (Figure 1).

Moreover, on the occasion of venomous snake bites, these are known to precipitate neurological symptoms such as weakness and paralysis, thus further highlighting the analogy. These are symptoms analogous to those that can occur with the various neurological conditions the aforementioned sign may be encountered with[11]. In contrast, terms like “owl’s eyes” and “snake eyes”, although visually descriptive, unfortunately, lack any relevant clinical correlation or educational value beyond this superficial resemblance. Using the term “snake bite sign” effectively combines a visual metaphor with a clinical symptomatology, thus augmenting its educational value and increasing the chances of recall when necessary. It is important to note that the term “snake bite sign” is not intended to imply that the underlying pathology involves an actual snake bite to the spinal cord. Rather, it metaphorically represents the visual resemblance of the bilateral punctate hyperintensities to fang marks and draws an illustrative parallel to the neurological impairment that might theoretically occur from a spinal snake bite, whether venomous or purely traumatic. This analogy is meant to enhance recognition and retention of the imaging pattern, not to assign a specific etiology.

We advocate for the term “snake bite sign” as a most appropriate or at least an alternative descriptor for spinal cord pathologies such as ischemia when symmetrical ovoid or circular high-T2-signal-intensity lesions are demonstrated on axial images. Adopting such meaningful terminology promotes a deeper understanding and more effective com

| 1. | Arkoudis NA, Velonakis G. Bilateral internal carotid dissection: advocating for the use of the "googly eyes sign''. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2025;54:526-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mawad ME, Rivera V, Crawford S, Ramirez A, Breitbach W. Spinal cord ischemia after resection of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms: MR findings in 24 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1303-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bekci T, Yucel S, Aslan K, Gunbey HP, Incesu L. "Snake eye" appearance on a teenage girl with spontaneous spinal ischemia. Spine J. 2015;15:e45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nogueira RG, Ferreira R, Grant PE, Maier SE, Koroshetz WJ, Gonzalez RG, Sheth KN. Restricted diffusion in spinal cord infarction demonstrated by magnetic resonance line scan diffusion imaging. Stroke. 2012;43:532-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weidauer S, Nichtweiss M, Lanfermann H, Zanella FE. Spinal cord infarction: MR imaging and clinical features in 16 cases. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:851-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang QY, Xu LY, Wang ML, Cao H, Ji XF. Spontaneous conus infarction with "snake-eye appearance" on magnetic resonance imaging: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:2074-2083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iacono S, Di Stefano V, Gagliardo A, Cannella R, Virzì V, Pagano S, Lupica A, Romano M, Brighina F. Hirayama disease: Nosological classification and neuroimaging clues for diagnosis. J Neuroimaging. 2022;32:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, Wirth B, Montes J, Main M, Mazzone ES, Vitale M, Snyder B, Quijano-Roy S, Bertini E, Davis RH, Meyer OH, Simonds AK, Schroth MK, Graham RJ, Kirschner J, Iannaccone ST, Crawford TO, Woods S, Qian Y, Sejersen T; SMA Care Group. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28:103-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khandelwal DC. Owl's eye sign: A rare neuroimaging finding in flail arm syndrome. Neurology. 2015;85:1996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fontanella MM, Zanin L, Bergomi R, Fazio M, Zattra CM, Agosti E, Saraceno G, Schembari S, De Maria L, Quartini L, Leggio U, Filosto M, Gasparotti R, Locatelli D. Snake-Eye Myelopathy and Surgical Prognosis: Case Series and Systematic Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Del Brutto OH, Del Brutto VJ. Neurological complications of venomous snake bites: a review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;125:363-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/