Published online May 28, 2025. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v17.i5.105785

Revised: March 29, 2025

Accepted: May 7, 2025

Published online: May 28, 2025

Processing time: 108 Days and 18.5 Hours

Calciphylaxis, also called calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is characterized by microvascular calcification and occlusion, which is commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Although several studies have demonstrated an association of calciphylaxis with ESRD, reports linking calciphylaxis to LT (LT) are scarce. This report presents a rare case of calciphylaxis in a patient who underwent LT, leading to microvascular occlusion and hyperbilirubinemia.

A 34-year-old man presented with a 7-day history of jaundice and severe bilateral leg pain. The patient had undergone LT and was put on hemodialysis for one year due to calcineurin inhibitor-induced ESRD. Physical examination revealed jaundice, leathery skin changes, severe muscle pain in both legs, and penile induration. Laboratory tests identified elevated bilirubin levels, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and alkaline phosphatase, while alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase concentrations were within normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) revealed extensive calcifications in the subcutaneous tissue. Three-dimensional CT reconstruc

This case indicates that calciphylaxis should be suspected in patients who have undergone LT with ESRD presenting with hyperbilirubinemia and skin lesions.

Core Tip: Calciphylaxis, a rare and life-threatening syndrome characterized by vascular calcification and tissue necrosis, predominantly affects end-stage renal disease patients. This case demonstrates the occurrence of calciphylaxis in a liver transplant recipient, presenting with multi-organ calcifications and hyperbilirubinemia caused by hepatic artery calcification. Early recognition of cutaneous and systemic calcification, combined with the management of metabolic dysregulation, is critical. This report indicates that calciphylaxis may be an unneglectable differential diagnosis for hyperbilirubinemia in transplant recipients and advocates for the development of preventive strategies in high-risk populations.

- Citation: Wei XL, Zhang YW, Han M, Sun CJ, Lai GZ, Tang SG, Ye RJ, Xu HQ, Wu LW, Xia WZ. Calciphylaxis following liver transplantation in a patient with end-stage renal disease: A case report. World J Radiol 2025; 17(5): 105785

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v17/i5/105785.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v17.i5.105785

Calciphylaxis is a rare and life-threatening syndrome which is common among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), with few cases detected in individuals without renal failure. The disease is characterized by calcification and occlusion of small to medium-sized blood vessels, which causes ischemia and necrosis of the surrounding tissues. It is estimated that the incidence of calciphylaxis varies across populations, ranging from 1 to 35 cases per 10000 patients[1-3]. Moreover, the overall prognosis is poor, with an average survival of approximately one year and an annual mortality rate exceeding 50%, most commonly induced by sepsis[4]. Clinically, calciphylaxis presents as chronic, painful, and non-healing ulcerative skin lesions, that is commonly accompanied by leathery skin changes in the abdomen, axilla, and lower limbs regions[5]. The key laboratory test findings include hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, increased accumulation of calcium-phosphorous products, increased alkaline phosphatase levels, and elevated concentration of creatinine. Although skin biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis, its diagnostic rate is reported to be 18%. In some cases, calcific deposits are detected in various organs, including the heart and eyes[6,7]. However, reports linking calciphylaxis to liver transplantation (LT) are rare in clinical practice. Here, we present a case of hyperbilirubinemia secondary to calciphylaxis in a patient who underwent LT.

A 34-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 10-day history of jaundice and intermittent abdominal pain.

The patient received LT in 2018 to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. He had been undergoing hemodialysis for one year, attributing his ESRD to calcineurin inhibitor toxicity. The patient reported a 10 kg unintentional weight loss over the preceding three months. Ten days before presentation, he developed intermittent abdominal pain accompanied by severe bilateral leg pain. He was subsequently admitted to undergo further evaluation and management.

On admission, the patient was receiving hemodialysis twice-weekly and had a history of hypertension for one year.

The patient’s personal and family history was negative.

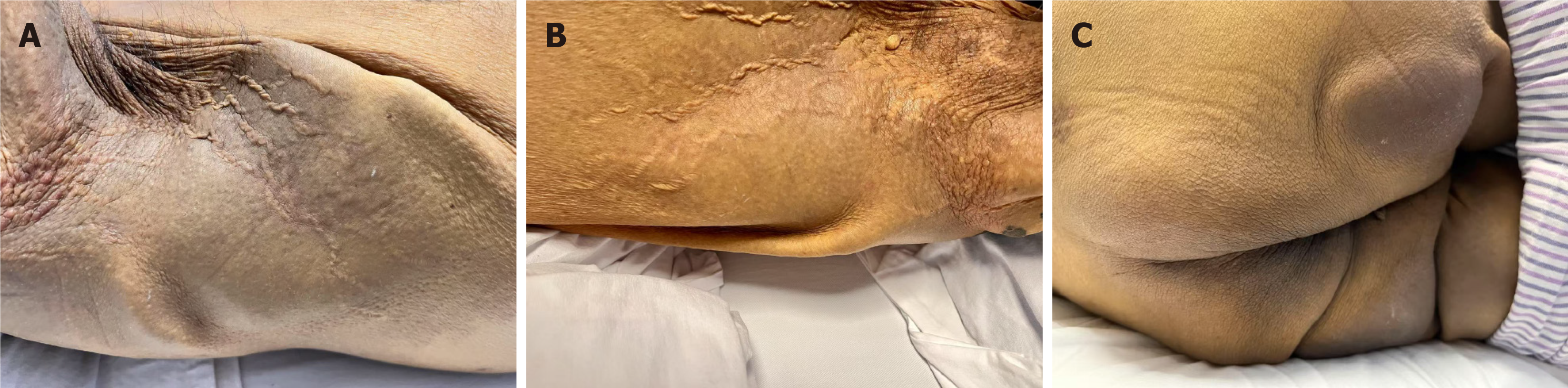

On examination, jaundice accompanied with icteric sclera, severe muscle pain in both legs, and intermittent abdominal pain were observed. In addition, firm, tender subcutaneous nodules were detected in the abdominal region on palpation. Tactile pain and dusky skin discoloration were noted in the hip region. Additionally, penile induration and leathery skin changes in the axillary and hip areas were observed (Figure 1).

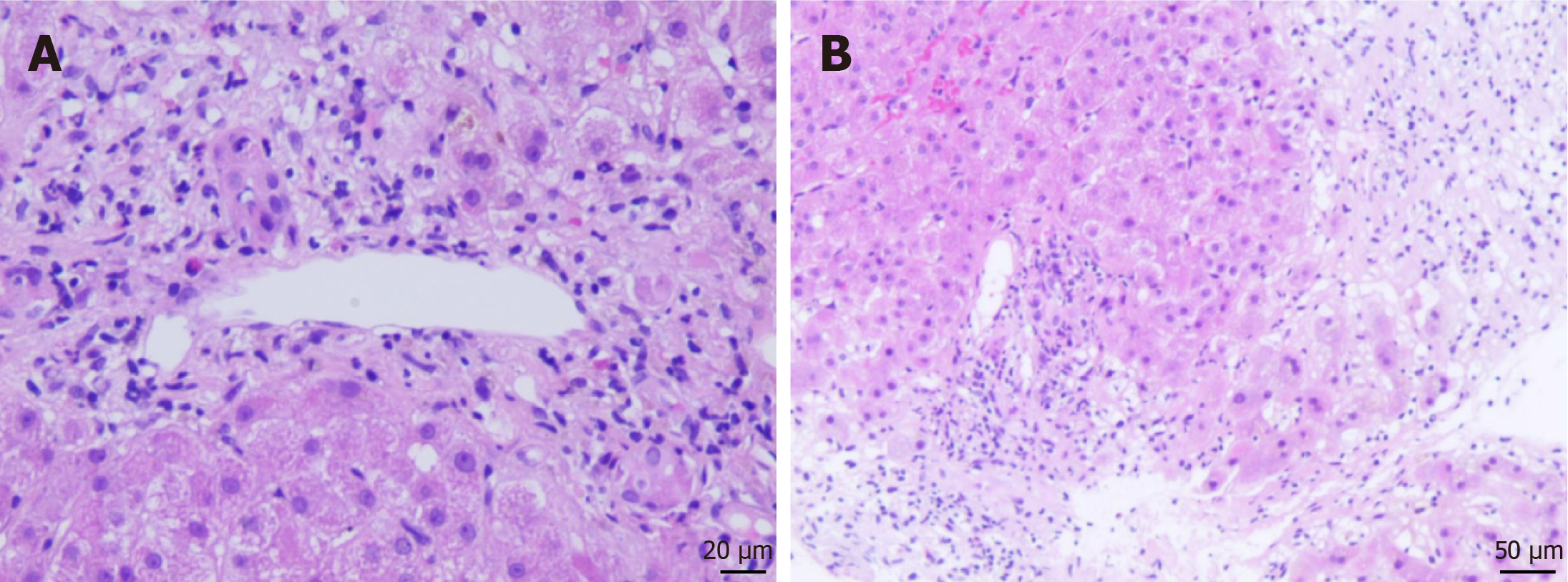

Laboratory tests revealed significantly elevated serum bilirubin levels, as well as total bilirubin (423 μmol/L) and direct bilirubin (303 μmol/L). The concentrations of gamma-glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase were elevated to 226 U/L and 261 U/L, while alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were within normal limits. Creatinine levels were markedly elevated to 1047 μmol/L, and the parathyroid hormone level increased to 233 pg/mL. Serum calcium and phosphorous levels were 2.4 mmol/L and 2.7 mmol/L, respectively. Liver biopsy revealed decreased arteriole and severe cholestasis (Figure 2). The Banff rejection active index was 2/9 (portal inflammation: 1 point; endophlebitis: 0 points; cholangitis: 1 point), confirming the absence of allograft rejection.

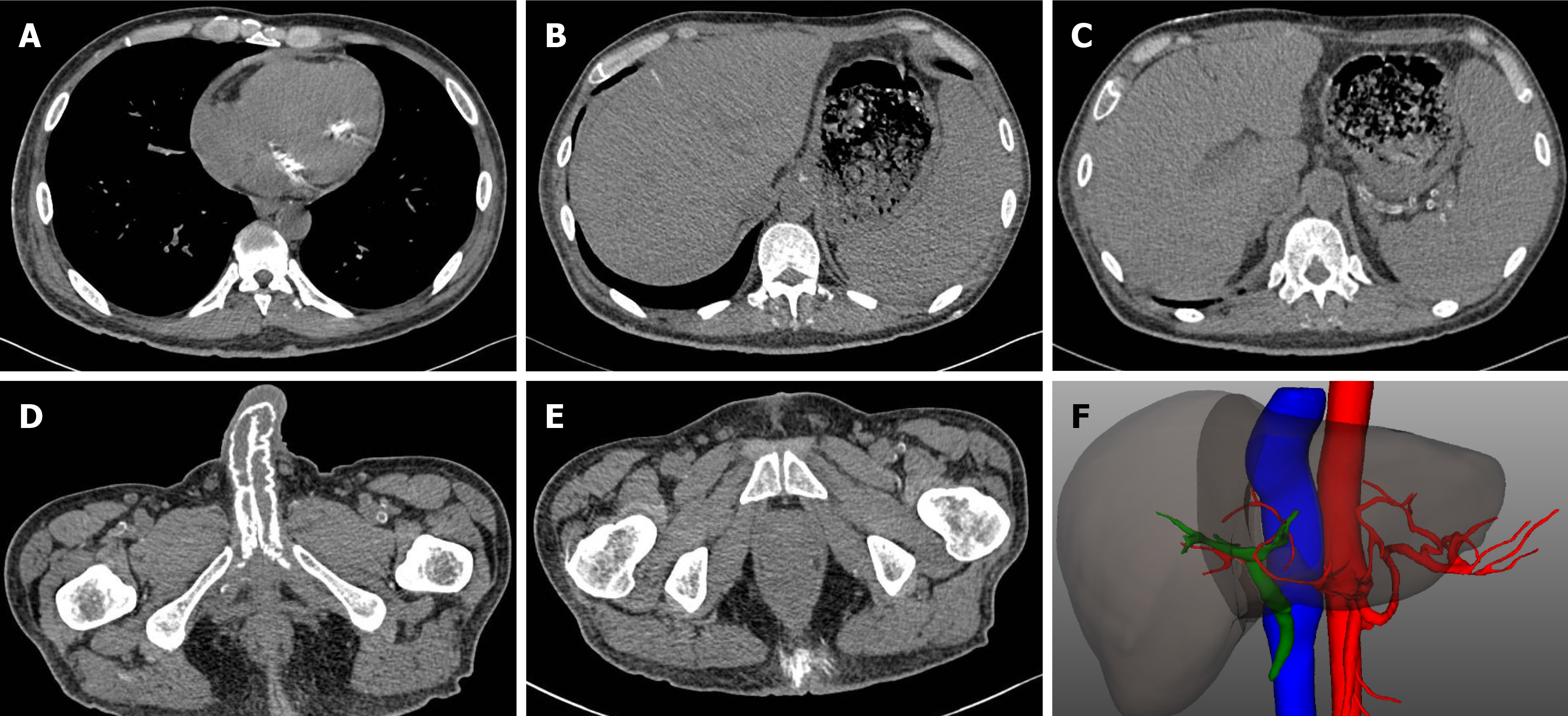

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed extensive calcifications in the subcutaneous tissues, bladder, penis, and bicuspid valve. Analysis of the three-dimensional CT reconstruction images demonstrated reduced blood flow in the hepatic artery, primarily in the small to medium-sized branches (Figure 3). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography did not find evidence of obstruction in the common bile duct or hepatic ducts. Additionally, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography confirmed hepatic ischemia, with no enhancement in hepatic artery branches.

Considering the patient’s history of ESRD, hemodialysis dependence, and extensive calcification, a diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made, together with application of the diagnostic criteria for calciphylaxis established by the Mayo Clinic.

Sodium thiosulfate is the first-line treatment for calciphylaxis[8]. Thus, the patient was scheduled to receive sodium thiosulfate at a dose of 25 g three times per week, combined with cinacalcet (30 mg daily) to manage hyperparathyroidism. His hemodialysis regimen was also adjusted, with both frequency and duration increased.

For personal reasons, the patient opted for conservative management at a local medical center. At the six-month follow-up, the patient succumbed to his illness.

In this paper, we report a patient with calciphylaxis following LT and ESRD, which caused hyperbilirubinemia post-transplant. The patient presented with severe leg pain, penile induration, and leathery skin changes. CT imaging revealed extensive calcification in the subcutaneous tissues, bladder, penis, and bicuspid valve. Moreover, there was a significant reduction in blood flow in the small to medium-sized hepatic artery branches. Further examination of liver biopsy found no evidence of allograft rejection. The patient opted to undergo conservative treatment and succumbed to the disease at the six-month follow-up.

Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a severe condition that predominantly affects patients with ESRD, characterized by progressive vascular calcification and occlusion in small to medium-sized vessels[4]. However, emerging evidence indicates that non-uremic calciphylaxis can occur in patients with preserved renal function[9]. In the present case, we identified an unusual presentation of calciphylaxis in a liver transplant recipient, which indicated a complex interplay between hepatic dysfunction, dysregulated calcium-phosphorus metabolism, and endothelial injury. Currently, there is no internationally recognized standard diagnostic criteria for calciphylaxis. According to the guidelines by the Mayo clinic, skin biopsy and clinical criteria should be included in the diagnosis[10]. In this case, the patient was receiving calcineurin inhibitors and other immunosuppressive agents. However, the ALT and AST were within normal limits, and histopathological examination showed no evidence of hepatocyte injury, thereby excluding drug-induced liver injury. Furthermore, serological tests for hepatitis B and C viruses were negative, and there was no histological evidence of viral hepatitis on biopsy. After exclusion of other causes, a diagnosis of calciphylaxis was made following the Mayo diagnostic criteria. The risk factors for calciphylaxis include ESRD, diabetes mellitus, hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperparathyroidism, elevated alkaline phosphatase, hepatobiliary disease, hypoalbuminemia, recurrent hypotension, and rapid weight loss, with ESRD being the most significant factor[5]. Factors associated with LT, including immunosuppressive therapy, metabolic derangements, and systemic inflammation, have been reported to increase the risk of vascular calcification and endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, studies have implicated hypoalbuminemia in the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis by altering calcium-phosphate homeostasis and increasing vascular mineral deposition[11]. Deficiency of vitamin K-dependent matrix Gla protein, a key inhibitor of vascular calcification, can also promote vascular mineral deposition[12,13]. Although direct evidence supporting the calciphylaxis-induced bile duct damage is lacking, further investigations into the hepatic manifestations of calciphylaxis in transplant recipients are advocated. Calcific deposits may occur in various organs, including the heart and eyes, leading to myocardial ischemia or visual impairment[6,7]. However, reports of calciphylaxis occurring in the liver are few. Raza et al[14] described a case of dystrophic calcification in a patient who underwent LT, inducing diffuse hepatic calcification, which was recognized as a differential diagnosis of calciphylaxis. In the present case, diffuse hepatic calcification was observed, accompanied with significant calcification in the cardiac valves, vessels, and penis. Dystrophic calcification is defined as a localized response to liver tissue damage, while calciphylaxis is a systemic vascular disorder driven by metabolic disturbances. The latter is severe, which can lead to high mortality. This case suggested that systemic vascular calcification may extend to hepatic arteries or the portal venous system, potentially impairing bile duct perfusion and contributing to biliary injury or cholestasis. However, the underlying mechanism of calciphylaxis are not clearly understood. The imbalance between calcification promoters and inhibitors, and vicious cycles of endothelial injury and microthrombosis may contribute to the pathogenesis of calciphylaxis[15-17].

The prognosis of calciphylaxis is poor, underscoring the importance of preventive measures. Currently, no specific biomarker could be used for early detection, but monitoring serum levels of calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) could be helpful for identifying metabolic imbalances that predispose to calciphylaxis. Additionally, regular imaging every 6–12 months in high-risk patients could detect early vascular calcifications. Eliminating risk factors could prevent or slow the development of calciphylaxis, reduce the length and frequency of the hemodialysis for ESRD patients, correct hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia, lower PTH level, and avoid subcutaneous injection[18,19]. Clinical studies have shown that supplementation of vitamin K (500 μg per day) slows the calcification by 6% at 3-year follow-up and help correct the disturbance of coagulation[20]. Furthermore, the patient was treated with intravenous sodium thiosulfate at a dosage of 25 g three times a week after dialysis sessions, which is considered the first-line treatment for calciphylaxis. To achieve optimal clearance of uremic toxins and maintain electrolyte balance, the dialysis protocol was optimized to include extended sessions of 5 hours each, three times a week. But calciphylaxis completely resolved in only 26%-52% patients receiving sodium thiosulfate[21,22].

In this case report, we discuss the occurrence of calciphylaxis leading to hyperbilirubinemia in a patient who underwent LT and ESRD. The patient presented with characteristic skin lesions and widespread calcium deposits, suggesting that the presence of these symptoms should raise suspicion of calciphylaxis, and skin biopsy should be conducted as the golden standard. Considering the poor prognosis and unsatisfactory therapeutic effects, strategies for eliminating risk factors and preventing its occurrence need to be developed.

| 1. | Nigwekar SU, Zhao S, Wenger J, Hymes JL, Maddux FW, Thadhani RI, Chan KE. A Nationally Representative Study of Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy Risk Factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3421-3429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Rothe H, Kaesler N, Korbiel J, Specht P, Schmitz S, Krüger T, Floege J, Ketteler M. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): data from a large nationwide registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rick J, Strowd L, Pasieka HB, Saardi K, Micheletti R, Zhao M, Kroshinsky D, Shinohara MM, Ortega-Loayza AG. Calciphylaxis: Part I. Diagnosis and pathology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:973-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nigwekar SU, Thadhani R, Brandenburg VM. Calciphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1704-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sivertsen MS, Strøm EH, Endre KMA, Jørstad ØK. Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Due to Calciphylaxis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2018;38:54-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alam S, Kirkwood K, Cruden N. Cardiac calciphylaxis presenting as endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | García-Lozano JA, Ocampo-Candiani J, Martínez-Cabriales SA, Garza-Rodríguez V. An Update on Calciphylaxis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yousuf S, Busch D, Renner R, Schliep S, Erfurt-Berge C. Clinical characteristics and treatment modalities in uremic and non uremic calciphylaxis - a dermatological single-center experience. Ren Fail. 2024;46:2297566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McCarthy JT, El-Azhary RA, Patzelt MT, Weaver AL, Albright RC, Bridges AD, Claus PL, Davis MD, Dillon JJ, El-Zoghby ZM, Hickson LJ, Kumar R, McBane RD, McCarthy-Fruin KA, McEvoy MT, Pittelkow MR, Wetter DA, Williams AW. Survival, Risk Factors, and Effect of Treatment in 101 Patients With Calciphylaxis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1384-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Armiento R, Gory I, Jenkins PJ, McLean CA. Calciphylaxis and hypoalbuminaemia. Med J Aust. 2012;196:249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wajih Z, Singer R. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with vitamin K in a patient on haemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nigwekar SU, Bloch DB, Nazarian RM, Vermeer C, Booth SL, Xu D, Thadhani RI, Malhotra R. Vitamin K-Dependent Carboxylation of Matrix Gla Protein Influences the Risk of Calciphylaxis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1717-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Raza A, Ahmed K, Rood RP. Diffuse hepatic calcification following ischemic insult in the setting of impaired renal function. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:A24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen TY, Lehman JS, Gibson LE, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA. Histopathology of Calciphylaxis: Cohort Study With Clinical Correlations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:795-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kramann R, Brandenburg VM, Schurgers LJ, Ketteler M, Westphal S, Leisten I, Bovi M, Jahnen-Dechent W, Knüchel R, Floege J, Schneider RK. Novel insights into osteogenesis and matrix remodelling associated with calcific uraemic arteriolopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:856-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nigwekar SU, Jiramongkolchai P, Wunderer F, Bloch E, Ichinose R, Nazarian RM, Thadhani RI, Malhotra R, Bloch DB. Increased Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling in the Cutaneous Vasculature of Patients with Calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46:429-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Baldwin C, Farah M, Leung M, Taylor P, Werb R, Kiaii M, Levin A. Multi-intervention management of calciphylaxis: a report of 7 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:988-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dobry AS, Ko LN, St John J, Sloan JM, Nigwekar S, Kroshinsky D. Association Between Hypercoagulable Conditions and Calciphylaxis in Patients With Renal Disease: A Case-Control Study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shea MK, O'Donnell CJ, Hoffmann U, Dallal GE, Dawson-Hughes B, Ordovas JM, Price PA, Williamson MK, Booth SL. Vitamin K supplementation and progression of coronary artery calcium in older men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1799-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D, Wang W, Hymes J, Lacson E Jr. Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1162-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zitt E, König M, Vychytil A, Auinger M, Wallner M, Lingenhel G, Schilcher G, Rudnicki M, Salmhofer H, Lhotta K. Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1232-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/