Published online Oct 28, 2024. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v16.i10.586

Revised: September 3, 2024

Accepted: September 13, 2024

Published online: October 28, 2024

Processing time: 161 Days and 20.8 Hours

Portal vein gas (PVG) is an abnormal accumulation of gas within the portal and intrahepatic portal veins. It is associated with various abdominal diseases, ranging from benign conditions to life-threatening ones that require immediate surgical intervention. Coronary angiography is the standard diagnostic procedure for coronary artery disease. There were no prior reports are available of PVG as a complication of coronary angiography.

In the specific case described here, the patient did not show signs of peritoneal irritation; however, computed tomography scans findings revealed pneumatosis in the wall of the small intestine, hepatic portal vein, and mesenteric vein, along with acute enteritis (etiology pending classification). A cesarean section was not performed, and the patient received treatment with fasting, rehydration, and anti-infection therapy. Subsequently, the patient's symptoms of abdominal distension and pain improved, and follow-up computed tomography scans indicated reso

Portal venous gas complication following coronary angiography was a com

Core Tip: Coronary angiography is the standard for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. No previous reports of portal vein gas complicated by coronary angiography. We now report a case of portal vein gas that occurred after coronary angiography in February 2024 in our hospital.

- Citation: Yu ZX, Bin Z, Lun ZK, Jiang XJ. Portal venous gas complication following coronary angiography: A case report. World J Radiol 2024; 16(10): 586-592

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v16/i10/586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v16.i10.586

Portal vein gas (PVG) is an abnormal accumulation of gas within the portal and intrahepatic portal veins. It is associated with various abdominal diseases, ranging from benign conditions to life-threatening ones that require immediate surgical intervention. Coronary angiography is the standard diagnostic procedure for coronary artery disease. Here were no prior reports are available of PVG as a complication of coronary angiography.

2024 for recurrent palpitations. These palpitations have been occurring for 3 years, but worsened in the last month.

A 71-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and arterial presystole was admitted to our hospital in February, 2024 for recurrent palpitations. These palpitations have been occurring for 3 years, but worsened in the last month. The patient had a body mass index of 22.48 kg/m2 and was otherwise asymptomatic.

Precoronary angiography evaluation revealed normal leukocyte, neutrophils, C-reactive protein, and glycosylated hemoglobin A1c levels (7.2%). A D-dimer of 0.63 mg/L and a 6-minute walk test distance of 389 meters were also recorded. Cardiac Doppler ultrasound showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (59%) and structure, and am

Twenty-four-hour ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring revealed 1936 premature atrial beats (2.2% of the total heart rate; 20 uninferiorized beats) and a maximum R-R interval of 2.0 seconds. A coronary angiography performed via radial artery, on February 26, 2024, showed 50%-60% stenosis in the mid-anterior descending branch.

With a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and arterial presystole.

A 71-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and arterial presystole was admitted to our hospital in February, 2024 for recurrent palpitations. These palpitations have been occurring for 3 years, but worsened in the last month. The patient had a body mass index of 22.48 kg/m2 and was otherwise asymptomatic.

The patient experienced no discomfort prior to the coronary angiography, which was completed at 13:28, but sub

During examination, the patient’s abdomen was soft, with no pressure, rebound pain, abdominal muscle tension, or hypertonic bowel sounds. After observing the abdominal symptoms for 30 minutes without improvement, the patient returned to the ward. However, on the way back, the patient reported worsening abdominal distension and noticeable bowel movements. Approximately 300 g of soft yellow stool was passed immediately upon returning to the ward, followed by two instances of yellow watery stool of unknown amounts. The patient began experiencing bloody stools at approximately 8:30 pm that night, with a total volume of 150 mL by 6:50 am the next morning. Additionally, transient sinus bradycardia was present, with a minimum ventricular rate of 34 beats/min. The patient also vomited a small amount of stomach contents, without any blood or coffee-colored material. During the checkup, the abdomen remained soft with no pressure, rebound pain, or abdominal muscle tension. Furthermore, no hypertonic bowel sounds were observed. By day 27th, the patient experienced significant relief from abdominal distension and pain, with no recurrence of bloody stools or diarrhea. After discharge from the hospital on March 10th, the patient is currently undergoing follow-up appointments and has not reported any recurrence of abdominal distention or pain.

Urgent stool bacterial cultures on March 4th did not detect any growth of bacteria, anaerobes, fungi, Shigella spp., or Salmonella spp. Laboratory tests revealed a leukocyte count of 5.98 × 109/L, neutrophil count of 62.80 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 122 g/L, ultrasensitive C-reactive protein level of 1.10 mg/L, calcitonin protein level less than 0.02 ng/mL, amylase level of 61 U/L, and lipase level of 30 U/L, and in the later hematologic examination and the stool bacterial culture did not reveal any signs of infection.

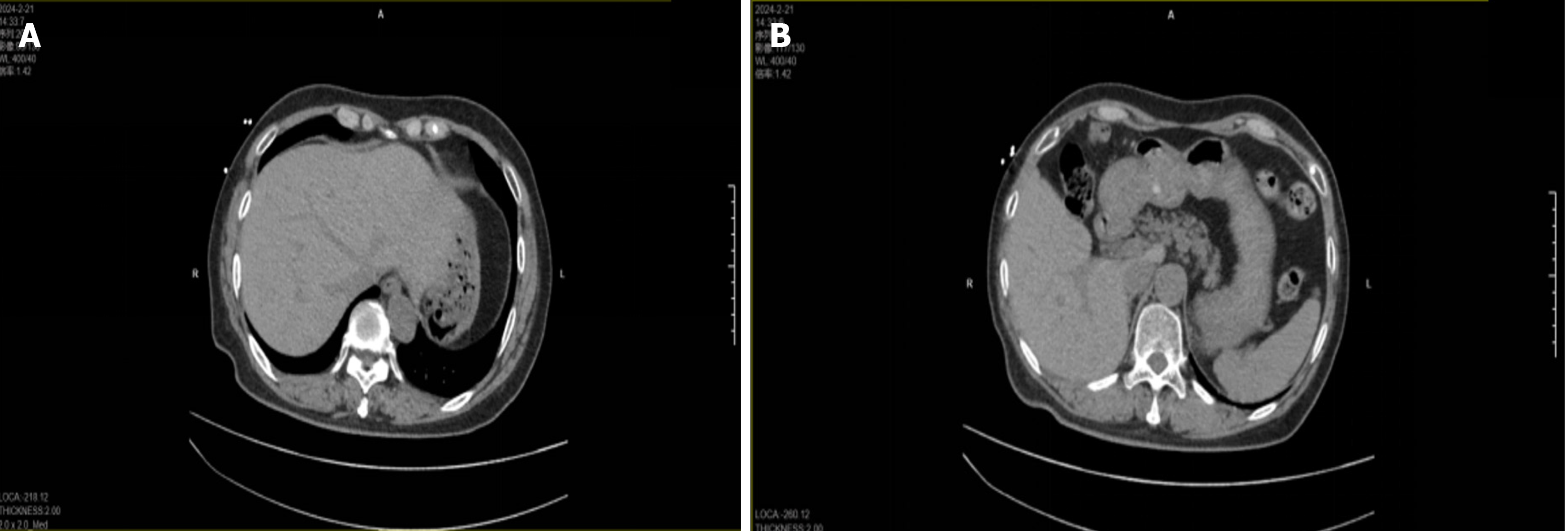

Computerized tomography scan on February 21, 2024, no portal venous effusion seen (Figure 1). Computerized tomo

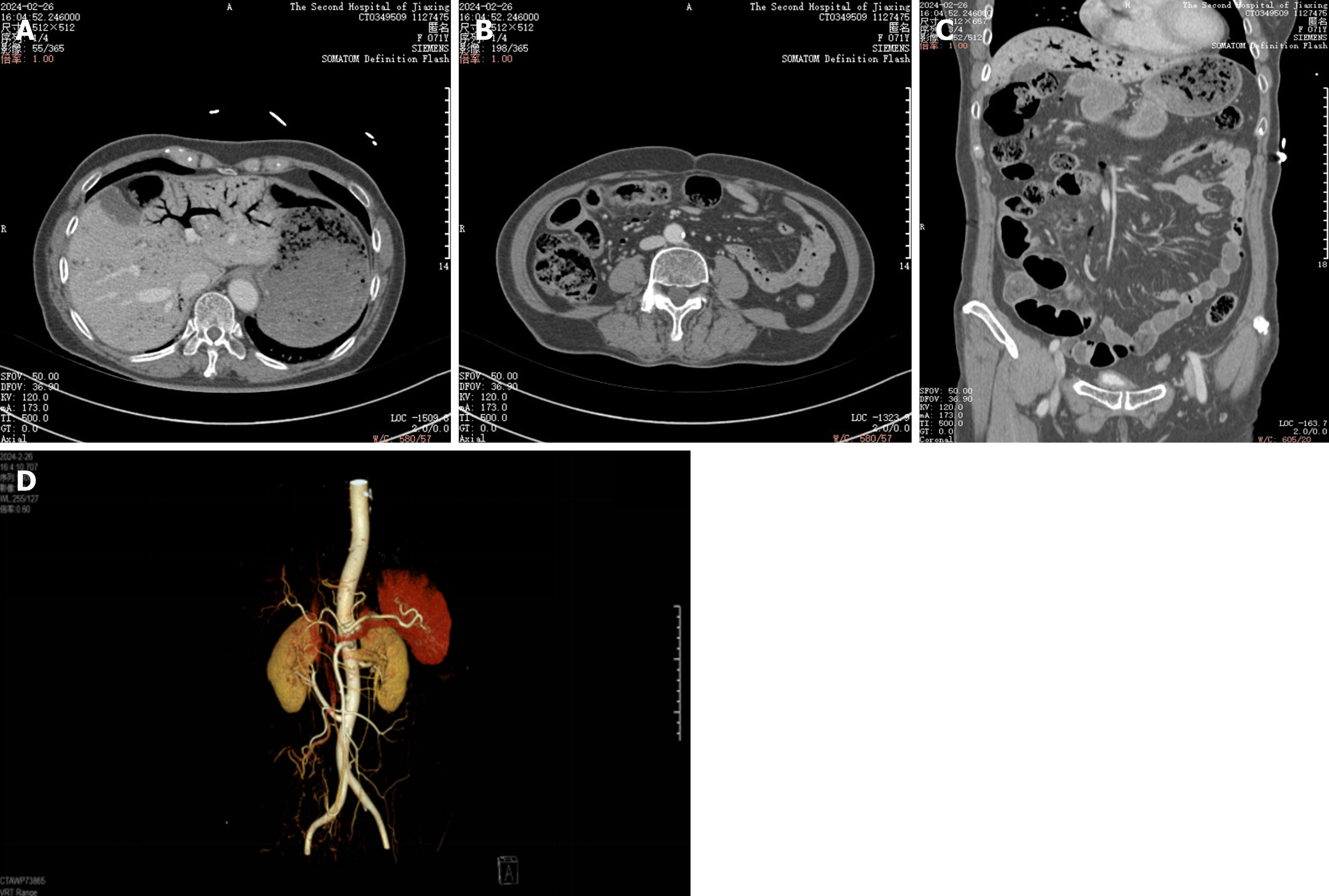

Multiple scattered gas in the superior mesenteric vein and its collateral branches (right middle and lower abdominal peristomal vessels), turbid spaces of the right middle and lower abdominal peristomal fat, and a localised small bowel wall in the right lower abdomen.

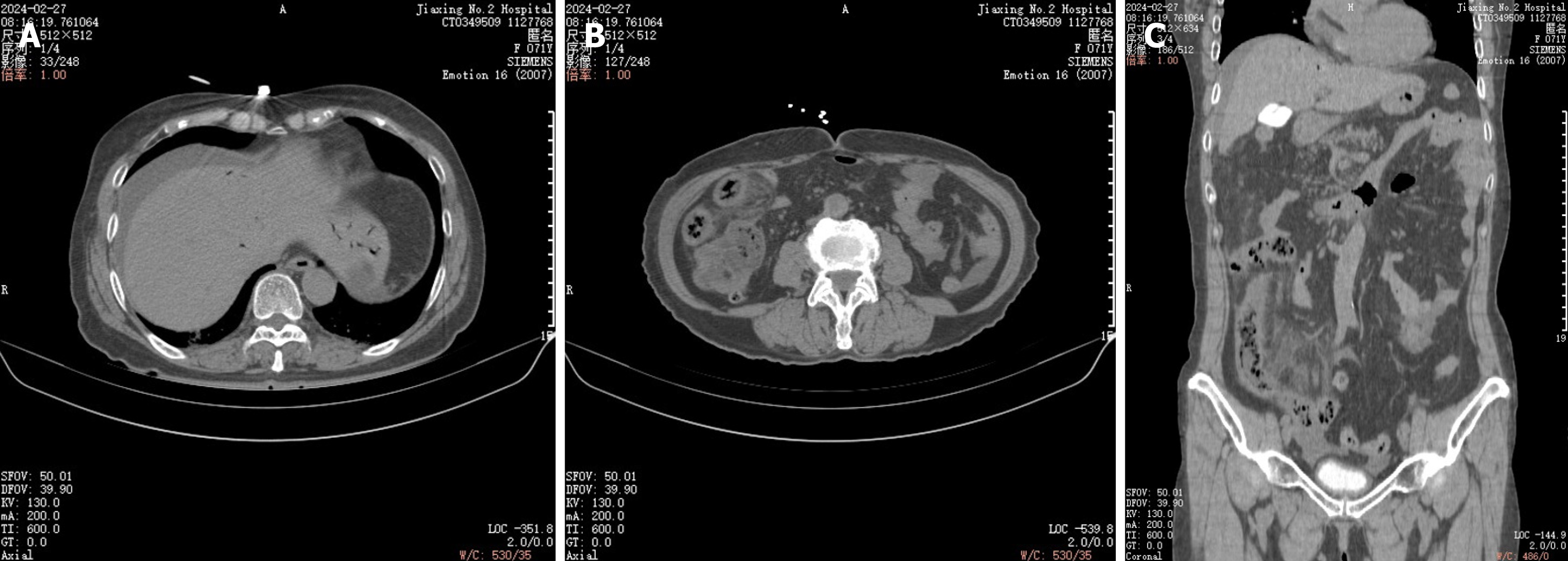

Comparison of computerized tomography scan on February 26, 2024, with necrosis of the bowel wall, peripheral exudative accumulation of mesenteric edema progressing more than before, and additional abdominopelvic effusion (Figure 4). Superior mesenteric vein and its collateral vessels with multiple pneumoperitoneum have been absorbed compared to before, and intrahepatic portal vein pneumoperitoneum has been significantly absorbed compared to before.

Computerized tomography scan on 10 March, 2024: Wall and mesenteric edema of the terminal ileum were better than before, and pelvic fluid was absorbed (Figure 5).

Portal venous gas complication following coronary angiography.

The patient received henbane 10 mg intravenously for rehydration. This provided mild relief from abdominal pain and distention, although the symptoms persisted. We reviewed previous case reports about portal venous gas then the patient was administered intravenous imipenem-cisplatin sodium every 6 hours. Considering the potential may need for a cesarean section, aspirin, clopidogrel bisulfate, and acarbose were discontinued. A 9 IU platelet transfusion was admi

Growth inhibitors were administered between February 27th and March 3th to alleviate gastrointestinal edema. Patient symptoms improved by February 28, and intravenous high-nutritional therapy was initiated. On March 3, the patient was transitioned to a fluid diet without any recurrence of abdominal distension, pain, diarrhea, or bloody stool after meals.

The patient continued to receive nifedipine controlled-release tablets (30 mg/d), temsirolimus (40 mg/d), and rosuvastatin (5 mg daily). The patient was discharged from the hospital on March 10th, and during the follow-up visits, no abdominal symptoms or bloody stools appeared.

In the specific case described here, the patient did not show signs of peritoneal irritation; however, computed tomo

Hepatic PVG (HPVG) is a significant radiological indicator often associated with serious abdominal conditions that may require immediate surgical treatment. HPVG typically has a sudden onset, progresses rapidly, and is associated with poor prognosis and high rates of morbidity and mortality. It can be linked to various underlying abdominal problems, some of which are life-threatening and require surgical intervention. Diagnosis of HPVG commonly involves abdominal radiography, ultrasound color Doppler flow imaging, or CT scans[1]. In a retrospective analysis by Hussain et al[2], among 275 patients with PVG, 70.5% experienced intestinal hypertension and ischemic disease, whereas 16.4% had infectious diseases of the abdominal cavity.

However, the mechanisms underlying the appearance of gas in the portal vein are poorly understood. Proposed factors that may predispose the portal venous system to gas accumulation include: (1) Ischemia-related PVG: Intestinal ischemia or infarction is a common and life-threatening abdominal disease, particularly in the elderly, with a mortality rate ranging from 75% to 90%. It is characterized by inadequate blood flow to the intestines and can be acute or chronic, depending on the underlying disease. Intestinal ischemia leads to damage to the mucosal barrier, dilation of the intestinal lumen, overgrowth of gas-producing bacteria, and migration of gases from the intestine to the mesenteric vein, eventually reaching the portal venous system and liver tissue. Intestinal ischemia is the primary cause of portal venous gas in approximately 70% of patients, and 91% of patients with this condition experience intestinal wall necrosis, resulting in a mortality rate of 85%[1]; (2) Infection-related PVG: This is primarily linked to inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and abdominal cavity, including conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal necrosis, abdominal abscess, diverticulitis, and pancreatitis. Two main contributing factors are: First, the proliferation of oxygen-producing bacteria in the intestinal tract generates significant amounts of gas that enters the portal system; second, various factors can cause the translocation of intestinal bacterial flora, allowing bacteria and endotoxins to breach the intestinal mucosal barrier and enter other organs[3]; (3) Mechanically related PVG: This condition is commonly associated with high pressure in the stomach and intestine, such as in cases of intestinal obstruction, abdominal trauma, gastrointestinal tumors, and gastric emphysema. Treatment varies depending on the specific trial, leading to inadequate blood flow to the intestine and resulting in secondary intestinal ischemia. This can lead to intestinal blockage and distention, resulting in damage due to the underlying disease; and (4) PVG in the medical phase: Medical interventions and drug administration can lead to bacterial overgrowth, ultimately causing intestinal gas and pneumatosis.

There have been no reported cases of coronary angiography that complicates the pneumoperitoneum in the portal system. There are 3 potential causes for the current etiology of this patient: (1) Coronary angiography manipulation factors: Gas or other acute mesenteric embolism, enhanced CT scans did not support the conjecture; (2) Drugs: Coronary angiography agents: Iohexol injection, heparin sodium injection, lidocaine hydrochloride, but none of the related drugs have been reported in the past to cause pneumoperitoneum in the portal vein; and (3) Sympathetic excitation and mesenteric artery spasm during coronary angiography lead to acute ischemic necrosis of the intestines and cause portal venous gas. And we think the point 3 is the most possible reason.

The primary symptoms of HPVG include varying degrees of abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. While some cases of HPVG can be managed conservatively with gastrointestinal decompression, anti-infection measures, rehydration, and close monitoring of the patient’s condition are essential to promptly determine the need for surgery. Current consensus suggests that urgent surgical intervention is warranted in cases where patients exhibit clinical signs of peritoneal irritation and shock, or CT scans reveal indications of free gas in the abdominal cavity, mesenteric embolism, and intestinal necrosis.

In the specific case described here, the patient did not show signs of peritoneal irritation; however, CT scans findings revealed pneumatosis in the wall of the small intestine, hepatic portal vein, and mesenteric vein, along with acute enteritis (etiology pending classification). A cesarean section was not performed, and the patient received treatment with fasting, rehydration, and anti-infection therapy. Subsequently, the patient's symptoms of abdominal distension and pain improved, and follow-up CT scans indicated resolution of the portal system pneumatosis and intestinal wall edema, resulting in a favorable clinical outcome.

| 1. | Chung SM, Kim KH, Kim KO, Kim TN. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Hepatic portal vein gas accompanied by acute enterocolitis improved with non-surgical treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hussain A, Mahmood H, El-Hasani S. Portal vein gas in emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ikegame K, Iimuro Y, Furuya K, Nakagomi H, Omata M. A case with hepatic portal vein gas who required delayed elective surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;65:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/