Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114983

Revised: October 25, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 128 Days and 21.7 Hours

Severe aortic stenosis is typically treated with transcatheter aortic valve im

To determine survival and predictors of mortality in patients older than 85 years who underwent TAVI.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 64 patients ≥ 85 years of age who underwent TAVI between 2010 and 2023 at the King Abdulaziz Cardiac Center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Baseline demographics, echocardiographic parameters, procedural outcomes, and mortality data were collected and analyzed at the 1-year and 3-year follow-up appointments.

The mean patient age was 88.3 ± 3.6 years, and 81.3% of the patients were male. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (79.7%), diabetes (60.9%), and coronary artery disease (53.1%). The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 51.1% with a mean transvalvular gradient of 45.1 mmHg. The 1-year and 3-year survival rates were 82% and 63%, respectively. The mean survival duration was 56.3 months. Multivariate analysis identified body mass index ≥ 30 as significant predictor of early mortality (odds ratio: 3.13, 95% confidence interval: 1.01-4.75).

Favorable survival outcomes were observed in patients 85 years or older who underwent TAVI. The mortality risk increased in patients with obesity.

Core Tip: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) demonstrated favorable mid-term survival in our cohort of elderly patients aged 85 years or older. The 1-year and 3-year survival rates were 82% and 63%, respectively. Mortality risk increased in patients with obesity. Advanced age alone should not be a contraindication for TAVI.

- Citation: Algethami A, Alahmadi SS, AlQahtani A, Balghith M. Survival outcomes of elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation after 3 years of follow-up. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 114983

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/114983.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.114983

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is currently the standard treatment for patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) and patients with contraindications for surgical replacement. TAVI has excellent mortality, morbidity, and quality of life outcomes[1]. Particularly, patients treated with TAVI experience fewer postoperative complications and shorter hospital stays when compared with patients who undergo surgical intervention.

Clinicians typically choose between TAVI or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) to treat patients with severe AS. The primary consideration is the age of the patient. Several scoring systems including the Society of Thoracic Surgeons score and EuroSCORE use age to determine the patient’s surgical risk. However, there are few studies in which a large patient cohort with advanced age (> 80 years) has been investigated. The EuroSCORE only enrolled 21 patients (out of the 19030) who were older than 90 years[2]. In addition to the scoring systems, age alone is currently sufficient to determine the management modality for AS. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines recommend TAVI instead of SAVR in patients older than 80 years or with life expectancy < 10 years. The European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Cardio Thoracic Surgery guidelines recommend TAVI for patients older than 75 years[3].

Three studies have shown that TAVI is noninferior to SAVR in the advanced age population. The first study observed that all-cause 1-year mortality was similar between patients aged 70 and older receiving TAVI or SAVR[4]. In another study in which individuals who were at high risk were investigated, a subgroup analysis of patients over 85 years demonstrated that TAVI was noninferior to SAVR[5]. The final study assessed survival after 5 years and found that TAVI was noninferior to surgical intervention[6].

Despite these promising observations there is a significant lack in research and follow-up on TAVI-related outcomes in elderly populations older than 85 years of age. This study was undertaken to fill this gap and determine mid-term sur

This study was retrospective cohort study spanning 14 years. It was conducted in the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. We included 64 consecutive patients who underwent TAVI at our center between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2023. We gathered qualitative and quantitative data (baseline characteristics, echocardiographic parameters, follow-up data, and mortality) from patient medical records after ethical approval from the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center Institutional Review Board (No. NRC24R/087/01). Primary endpoints were the mid-term clinical and echocardiographic outcomes, and secondary endpoints included predictors of mortality and periprocedural complications.

Patients who were older than 85 years and had severe symptomatic AS (defined as mean gradient ≥ 40 mmHg and/or aortic valve area ≤ 1 cm2) were included. The multidisciplinary heart team had assessed each case to determine the appropriate intervention. Treatment modality had been determined upon consideration of each patient’s demographics, anatomy, underlying comorbidities, and procedural cumulative risk as calculated by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons score.

Preprocedural echocardiography was performed in all patients to determine the right and left ventricular size and function, aortic valve morphology, aortic valve area, and cause of aortic disease. The ejection fraction of the left ventricle and the severity of other valve disease were determined. In addition to a post procedural echocardiography, percu

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and compared using the χ2 test; when expected counts were < 5, Fisher’s exact test was applied. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed with the student’s t-test for normally distributed data, while the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for non-normal data. Paired t-tests were used for repeated echocardiographic measures. Survival was evaluated with Kaplan-Meier analysis, and predictors of mortality were assessed with multivariate logistic regression, reporting odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were recorded using Microsoft Excel and analyzed with SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

The baseline characteristics of the 64 patients who underwent TAVI are presented in Table 1. The majority of the patients were male (81.3%) and obese (46.9%) or overweight (32.8%). The most common comorbidities included hypertension (79.7%), diabetes mellitus (60.9%), and dyslipidemia (48.4%). Other conditions such as smoking history (9.4%), dementia (6.3%), and cancer during the prior 5 years (3.1%) were documented. The patients experienced various cardiovascular issues including coronary artery disease (53.1%), history of myocardial infarction (25.0%), and heart failure (15.6%). Vessel involvement was noted in > 50.0% of the patients. However, 46.9% of the patients did not have specific data. Hematological investigations reflected average values for creatinine, hematocrit, WBC count, and platelet count.

| Variable | Category | Data |

| Sex | Male | 52 (81.3) |

| Female | 12 (18.8) | |

| Age in years | 88.3 ± 3.6 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 1 (1.6) |

| Normal | 12 (18.8) | |

| Overweight (BMI > 30) | 21 (32.8) | |

| Obese (BMI > 35) | 30 (46.9) | |

| Medical history | Diabetes mellitus | 39 (60.9) |

| Hypertension | 51 (79.7) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 31 (48.4) | |

| Dementia | 4 (6.3) | |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 1 (1.6) | |

| Immunocompromised | 0 (0) | |

| Mediastinal radiotherapy | 0 (0) | |

| Cancer within 5 years | 2 (3.1) | |

| Smoking | 6 (9.4) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 (0) | |

| ESRD | 5 (7.8) | |

| Dialysis | 0 (0) | |

| Previous cardiac intervention | 24 (37.5) | |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 8 (12.5) | |

| History of MI | 16 (25.0) | |

| Coronary artery disease | 34 (53.1) | |

| Heart failure | 10 (15.6) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0 (0) | |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 8 (12.5) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (7.8) | |

| Sleep apnea | 1 (1.6) | |

| Liver disease | 1 (1.6) | |

| COPD | 3 (4.7) | |

| Oxygen dependence | 1 (1.6) | |

| Carotid artery disease | 1 (1.6) | |

| Pacemaker insertion | 1 (1.6) | |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs ≤ 48 hours | 27 (42.2) | |

| First degree heart block | 2 (3.1) | |

| Bundle branch block | 4 (6.3) | |

| Fascicular block | 0 (0) | |

| Second degree heart block | 1 (1.6) | |

| Numbers of vessels > 50% | No significant disease | 30 (46.9) |

| 1 | 14 (21.9) | |

| 2 | 7 (10.9) | |

| 3 | 11 (17.2) | |

| NYHA classification | 1 | 5 (7.8) |

| 2 | 13 (20.3) | |

| 3 | 35 (54.7) | |

| 4 | 10 (15.6) | |

| Data not available | 1 (1.6) | |

| Hematological investigations as mean ± SD | Creatinine (normal range: 44-106 mol/L) | 94.02 ± 31.60 |

| Hematocrit (normal range: 0.42-0.54 L/L) | 36.16 ± 6.90 | |

| WBC (normal range: 4-11 × 106 g/L) | 6.93 ± 2.40 | |

| Platelets (normal range: 150-400 × 109 g/L) | 251.84 ± 86.80 | |

Echocardiography revealed Table 2 predominantly preserved right ventricular function and size with a right ventricular size of 1 in 96.9% of patients. Pulmonary hypertension was observed in 1.6% of cases. Left ventricular function and size was normal in most patients (73.4% and 89.1%, respectively). Left ventricular function was mildly impaired in 7.8% of patients. Most patients (95.3%) had tricuspid valve morphology. Degenerative stenosis was the prevalent type of aortic valve disease (98.4%). Aortic insufficiency varied in severity, but the majority of patients were graded as mild (54.7%). The ejection fraction average was 51.09% ± 9.1%.

| Variable | Category | Data |

| RV function and RV size | 1 | 62 (96.9) |

| 2 | 1 (1.6) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 1 (1.6) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | No | 63 (98.4) |

| Yes | 1 (1.6) | |

| LV function | Normal | 47 (73.4) |

| Mild | 5 (7.8) | |

| Moderate | 9 (14.1) | |

| Severe | 3 (4.7) | |

| LV size | Normal | 57 (89.1) |

| Mild | 4 (6.3) | |

| Moderate | 2 (3.1) | |

| Severe | 1 (1.6) | |

| Aortic valve morphology | Bicuspid | 1 (1.6) |

| Tricuspid | 61 (95.3) | |

| Bio-prosthetic | 2 (3.1) | |

| Aortic valve disease | Degenerative stenosis | 63 (98.4) |

| Rheumatic aortic stenosis | 0 (0) | |

| Mixed AI/AS | 1 (1.6) | |

| Aortic insufficiency | None | 16 (25.0) |

| Mild | 35 (54.7) | |

| Moderate | 11 (17.2) | |

| Severe | 2 (3.1) | |

| Ejection fraction in mmHg | 51.09 ± 9.10 | |

| Peak Gradient in mmHg | 75.75 ± 23.40 | |

| Mean gradient in mmHg | 45.05 ± 13.60 | |

At the initial follow-up the mean gradient was 16.12 ± 7.4 mmHg while the mean gradient at the final follow-up was 8.60 ± 4.3 mmHg (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Follow-up | Gradient | Mean | SD | P value |

| 1 year | Mean gradient | 16.12 | 7.4 | < 0.001 |

| 3 years | Mean gradient | 8.60 | 4.3 |

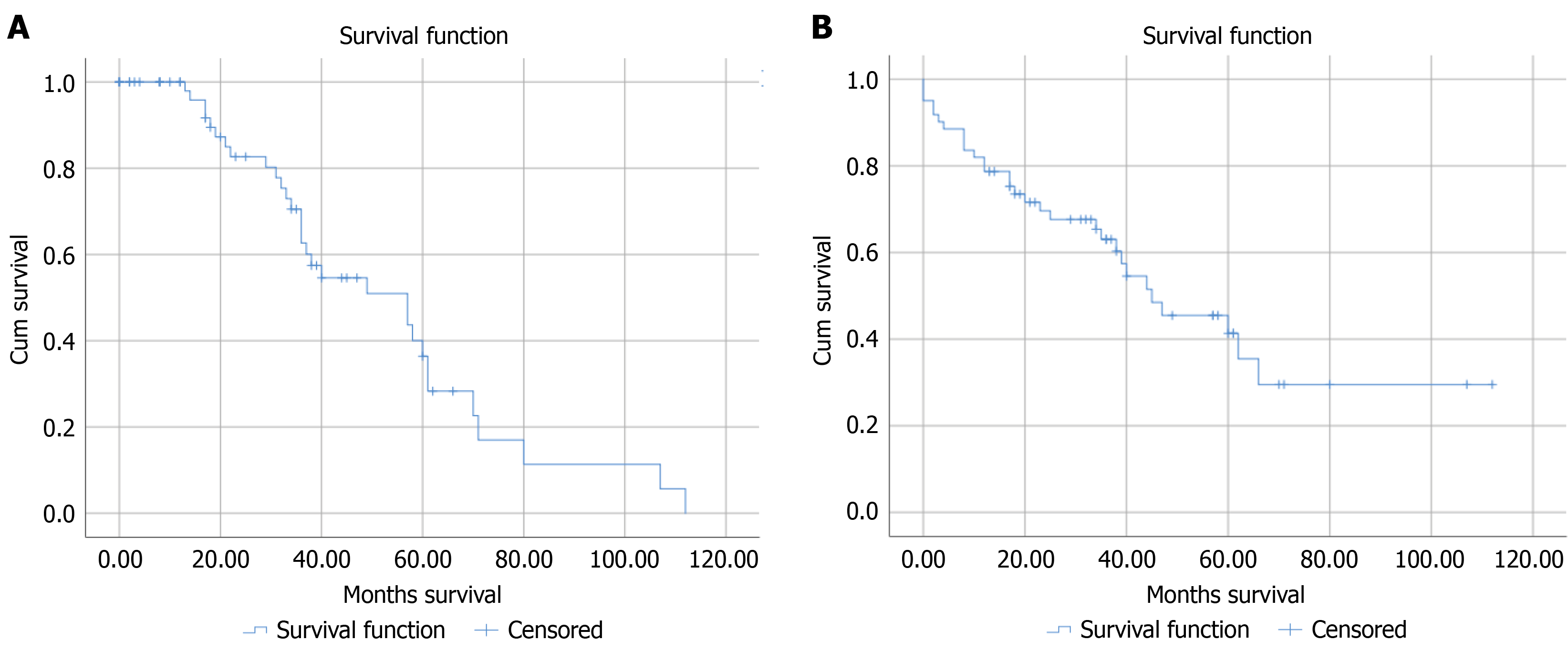

The estimated survival probabilities at 1 year and 3 years after TAVI were 0.82 and 0.63, respectively (Table 4 and Figure 1A suggesting a relatively high likelihood of survival. The Kaplan-Meier analysis after TAVI indicated a mean survival time of 55.47 months (95%CI: 42.62-68.34) with a standard error of 6.56. The median survival time was 44.00 months (95%CI: 25.50-64.50) with a standard error of 9.94 (Figure 1B).

| Interval start time in months | Number entering | Number withdrawing | Number exposed to risk | Number of terminal events | Proportion terminating | Proportion surviving | Cumulative proportion surviving |

| 0 | 61 | 0 | 61 | 11 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| 12 | 50 | 8 | 46 | 7 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.69 |

| 24 | 35 | 5 | 32.5 | 3 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.63 |

| 36 | 27 | 18 | 18 | 10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.32 |

All variables entered into the model were chosen a priori based on established clinical relevance and prior evidence from the literature on postoperative cardiac outcomes. Initially, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed for each potential predictor. Variables with a P value of ≤ 0.20 in univariate analysis or those deemed clinically important [i.e. age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, pulmonary hypertension] were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. A backward stepwise elimination approach was applied to reduce overfitting, retaining only variables that improved model fit based on the likelihood ratio test and Akaike Information Criterion. The final model was assessed for multicollinearity (variance inflation factor < 2) and goodness of fit using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Upon multivariate regression analysis, several factors were identified as increasing the mortality risk. The significant associations included higher BMI (OR: 3.13, 95%CI: 1.01-4.75, P = 0.042), pulmonary hypertension (OR: 9.14, 95%CI: 5.72-17.32, P = 0.021), and carotid artery disease (OR: 6.15, 95%CI: 2.43-9.31, P = 0.041). Male sex exhibited higher OR but was not statistically significant (OR: 6.38, 95%CI: 0.53-76.36, P = 0.144). Notably, diabetes and hypertension did have sig

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Male sex | 6.38 (0.53-76.36) | 0.144 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 3.13 (1.01-4.75) | 0.042 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.42 (0.08-2.20) | 0.301 |

| Hypertension | 0.71 (0.12-4.14) | 0.701 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4.20 (0.67-26.42) | 0.127 |

| Dementia | 0.16 (0.01-4.23) | 0.274 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 2.78 (1.01-4.57) | 0.876 |

| Cancer within 5 years | 0.83 (0.01-1.21) | 0.911 |

| Smoking | 2.59 (0.15-43.26) | 0.509 |

| ESRD | 1.23 (0.02-6.79) | 0.922 |

| Previous cardiac intervention | 0.98 (0.10-10.20) | 0.988 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 0.17 (0.01-4.10) | 0.277 |

| History of MI | 1.16 (0.19-7.01) | 0.873 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2.71 (0.31-23.30) | 0.365 |

| Numbers of vessels > 50% | 1.00 (0.91-1.11) | 0.942 |

| Heart failure | 0.27 (0.02-4.24) | 0.348 |

| NYHA classification > 4 | 1.05 (0.89-1.22) | 0.573 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1.11 (0.10-12.04) | 0.932 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.85 (0.06-12.87) | 0.907 |

| Sleep apnea | 0.42 (0.12-0.92) | 0.826 |

| Liver disease | 0.58 (0.20-0.91) | 0.887 |

| COPD | 1.96 (0.04-91.33) | 0.732 |

| Oxygen dependence | 3.55 (0.98-5.12) | 0.465 |

| Carotid artery disease | 6.15 (2.43-9.31) | 0.041 |

| Pacemaker insertion | 1.66 (0.15-2.43) | 0.912 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 9.14 (5.72-17.32) | 0.021 |

This study demonstrated that advanced age did not affect outcomes after TAVI when used to treat severe AS. Our cohort of 64 patients who were older than 85 years demonstrated a high survival rate and low complication rate 1 year and 3 years after undergoing TAVI. We found that a significant predictor of mortality was a BMI greater than 30.

Other studies investigating survival outcomes after the TAVI procedure had younger cohorts than in our study. Kapadia et al[7] and Makkar et al[8] recruited patients with mean ages of 83 years and 81.5 years, respectively. The mean age of our cohort was 88 years. The survival rates in both studies were comparable to our study. Kapadia et al[7] observed 1-year and 3-year survival rates of 68.7% and 45.1%, respectively. Makkar et al[8] measured survival rates at 2 years and 5 years of 83.3% and 54.0%, respectively. These survival outcomes were similar to our predicted survival rates of 82% (1-year) and 63% (3-year). Our analysis of our patients demonstrated a 1-year survival rate of 82% and a 3-year survival rate of 63% with a mean survival of 56 months.

We identified several factors that were predictive of survival in our cohort, most notably a BMI greater than 30, which was prevalent among the studied patients and therefore provided sufficient power for the analysis. Other factors, such as carotid artery disease and pulmonary hypertension, were also associated with increased mortality; however, their rarity within the cohort limited the strength and reliability of the associations. The small number of events for these predictors likely reduced statistical power and increased the risk of overestimating effect sizes.

There were some limitations in our study. The relatively small sample size (n = 64) inherently limits the statistical power of the study and may contribute to wide CIs, particularly in the multivariate regression analysis. Although several predictors of mortality remained significant, the limited cohort size restricts the stability and generalizability of these findings, especially for rare events like pulmonary hypertension and carotid disease. Moreover, the study spans a 14-year period (2010-2023), during which evolution occurred in TAVI technology, valve design, operator experience, and patient selection. This introduces a potential ‘era effect’, whereby early outcomes associated with less mature technology may dilute or obscure improvements achieved in more recent years. In addition, the retrospective and single-center design of the study inherently limits its generalizability. Future studies with larger, temporally stratified cohorts are warranted to validate these results and to better delineate the impact of technological advancement on long-term outcomes in elderly TAVI populations.

In an elderly population older than 85 years, TAVI was associated with high probability of survival after 1 year and 3 years. A BMI greater than 30 was linked to increased mortality, indicating that careful selection of advanced aged pa

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Fawaz Pullishery for his valuable contribution to the statistical analysis and interpretation of the study data.

| 1. | Thyregod HGH, Jørgensen TH, Ihlemann N, Steinbrüchel DA, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, De Backer O, Olsen PS, Søndergaard L. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation: 10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1116-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 117.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, Cortina J, David M, Faichney A, Gabrielle F, Gams E, Harjula A, Jones MT, Pintor PP, Salamon R, Thulin L. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:816-22; discussion 822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1147] [Cited by in RCA: 1152] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee G, Chikwe J, Milojevic M, Wijeysundera HC, Biondi-Zoccai G, Flather M, Gaudino MFL, Fremes SE, Tam DY. ESC/EACTS vs. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of severe aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:796-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | UK TAVI Trial Investigators; Toff WD, Hildick-Smith D, Kovac J, Mullen MJ, Wendler O, Mansouri A, Rombach I, Abrams KR, Conroy SP, Flather MD, Gray AM, MacCarthy P, Monaghan MJ, Prendergast B, Ray S, Young CP, Crossman DC, Cleland JGF, de Belder MA, Ludman PF, Jones S, Densem CG, Tsui S, Kuduvalli M, Mills JD, Banning AP, Sayeed R, Hasan R, Fraser DGW, Trivedi U, Davies SW, Duncan A, Curzen N, Ohri SK, Malkin CJ, Kaul P, Muir DF, Owens WA, Uren NG, Pessotto R, Kennon S, Awad WI, Khogali SS, Matuszewski M, Edwards RJ, Ramesh BC, Dalby M, Raja SG, Mariscalco G, Lloyd C, Cox ID, Redwood SR, Gunning MG, Ridley PD. Effect of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation vs Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Aortic Stenosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327:1875-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4547] [Cited by in RCA: 5048] [Article Influence: 336.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Douglas PS, Anderson WN, Blackstone EH, Kodali SK, Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Kapadia S, Bavaria J, Hahn RT, Thourani VH, Babaliaros V, Pichard A, Herrmann HC, Brown DL, Williams M, Akin J, Davidson MJ, Svensson LG; PARTNER 1 trial investigators. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2477-2484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1153] [Cited by in RCA: 1394] [Article Influence: 126.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Agarwal S, Kodali S, Fontana GP, Webb JG, Mack M, Thourani VH, Babaliaros VC, Herrmann HC, Szeto W, Pichard AD, Williams MR, Anderson WN, Akin JJ, Miller DC, Smith CR, Leon MB. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation. 2014;130:1483-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, Kodali SK, Kapadia S, Webb JG, Yoon SH, Trento A, Svensson LG, Herrmann HC, Szeto WY, Miller DC, Satler L, Cohen DJ, Dewey TM, Babaliaros V, Williams MR, Kereiakes DJ, Zajarias A, Greason KL, Whisenant BK, Hodson RW, Brown DL, Fearon WF, Russo MJ, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Jaber WA, Rogers E, Xu K, Wheeler J, Alu MC, Smith CR, Leon MB; PARTNER 2 Investigators. Five-Year Outcomes of Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:799-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 102.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/