Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.112466

Revised: October 5, 2025

Accepted: November 20, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 171 Days and 7 Hours

Long coronavirus disease (LC) is a condition characterized by a persistent state, with recurrent/remitting or progressive episodes, that may affect one or multiple organ systems following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in

Core Tip: Long coronavirus disease (LC) is often accompanied by continuing cardiovascular complications, yet objective tools for diagnosis, risk stratification, and therapeutic monitoring remain limited. This review explores unresolved mechanisms and critically examines the role of conventional and emerging biomarkers in the cardiovascular sequelae of LC. We provide a critical appraisal of evidence strength and highlight gaps in clinical translation, including assay standardization, accessibility, and validation. Finally, we propose multimarker strategies and omics-based approaches as promising tools to support personalized interventions and improve long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with LC within clinical practice.

- Citation: Aguiar CEO, Costa JMC, Oliveira MMGL, Lopes CF, Lima PHM, Dietrich VC, Grenfell RFQ, de Melo FF. Cardiovascular burden of long coronavirus disease: Clinical challenges and emerging biomarkers. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 112466

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/112466.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.112466

The long-term sequelae of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continue to challenge healthcare systems globally[1]. Long COVID (LC) is defined by the World Health Organization as a range of symptoms that usually start within 3 months of the initial COVID-19 illness and last at least 2 months, often without an alternative diagnosis[2]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, on the other hand, considers conditions that persist or appear four weeks or more after the initial infection, a definition adopted by several countries worldwide[3]. These differing case definitions of LC create considerable challenges in estimating the extent of the problem due to variations in the criteria used to identify and classify such cases. Terms like “long-haul COVID”, “chronic COVID”, “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19” (PASC), and “post-COVID syndrome” are also used[4].

Studies on the global prevalence of LC vary in the percentage of the population affected, depending on the country and cohort evaluated. The World Health Organization estimates that 10%-20% of patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) develop LC[5]. According to the meta-analysis by Muthuka et al[6], the prevalence of LC varies widely, with an estimated average of 42.5%, ranging from 1.6% to 82% across different populations and studies. Moreover, patients with pre-existing disabilities present an even higher prevalence compared to the general population (40.6% vs 18.9%)[7]. Cardiovascular symptoms are frequent, studies with 3-12 months of follow-up estimate a prevalence of 22% for chest pain, 18% for palpitations, and 19% for new-onset hypertension[8]. Other reported signs include chronic dyspnea (affecting approximately 21%-37%) and severe fatigue (reported in 27%-57%)[9].

These post-infectious manifestations are multisystemic and may affect almost any organ, including the heart and vasculature, lungs, nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine system, with particularly notable cardiovascular involvement[9,10]. Notably, while individuals who experienced severe acute COVID-19 are at greater risk of acute cardiovascular sequelae, those with mild cases may also present with persistent cardiovascular symptoms in the long term. This observation suggests that initial disease severity is not the sole determinant of long-term cardiovascular outcomes[11]. However, many studies lack comprehensive information regarding patients’ pre-existing conditions, comorbidities, and the severity of the acute infection, limiting the ability to determine the extent to which persistent symptoms are exclusively attributable to SARS-CoV-2 sequelae or influenced by predisposing factors. Additionally, diverse forms of cardiovascular involvement, including functional, inflammatory, hemodynamic, and structural abnormalities, have been widely documented in individuals with LC[12].

The lack of specific diagnostic tools and the variety of cardiovascular manifestations complicate diagnosis[13], there is a growing need for more precise diagnostic tools. Conventional diagnostic methods may fail to detect subtle or diffuse impairments that do not initially result in evident structural damage[10]. In this scenario, biomarkers, such as myocardial injury, cardiac stress, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy, may provide an objective measurement of pathophysio

We conducted a narrative review of the literature on cardiovascular biomarkers in LC, searching PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library up to July 15, 2025. The following search string was applied: (“Long COVID” OR “post-acute sequelae of COVID-19” OR “post-COVID condition” OR “PASC” OR “chronic COVID”) AND (“biomarker” OR “biomarkers” OR “cardiac biomarkers” OR “inflammatory biomarkers” OR “molecular markers” OR “microRNA” OR “miRNA” OR “galectin-3” OR “troponin” OR “NT-proBNP” OR “IL-6” OR “D-dimer”) AND (“cardiovascular” OR “cardiac” OR “heart” OR “myocarditis” OR “arrhythmia” OR “heart failure” OR “endothelial dysfunction”). We included original studies and relevant reviews, without initial language restrictions, but prioritized articles published in English. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, populations, and outcomes, no meta-analysis was performed. Instead, we conducted a qualitative synthesis of the findings, highlighting consistent patterns, methodological limitations, and knowledge gaps.

It is well established that SARS-CoV-2 enters human cells through binding of its spike protein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, followed by spike protein priming via cleavage by the transmembrane serine protease 2[15,16]. When linking specific infection mechanisms to the emergence of cardiovascular symptoms in LC, it is noteworthy that these receptors are expressed by endothelial cells, pericytes, and cardiomyocytes[17-19]. However, the potential for direct viral invasion of heart tissue remains a subject of ongoing debate.

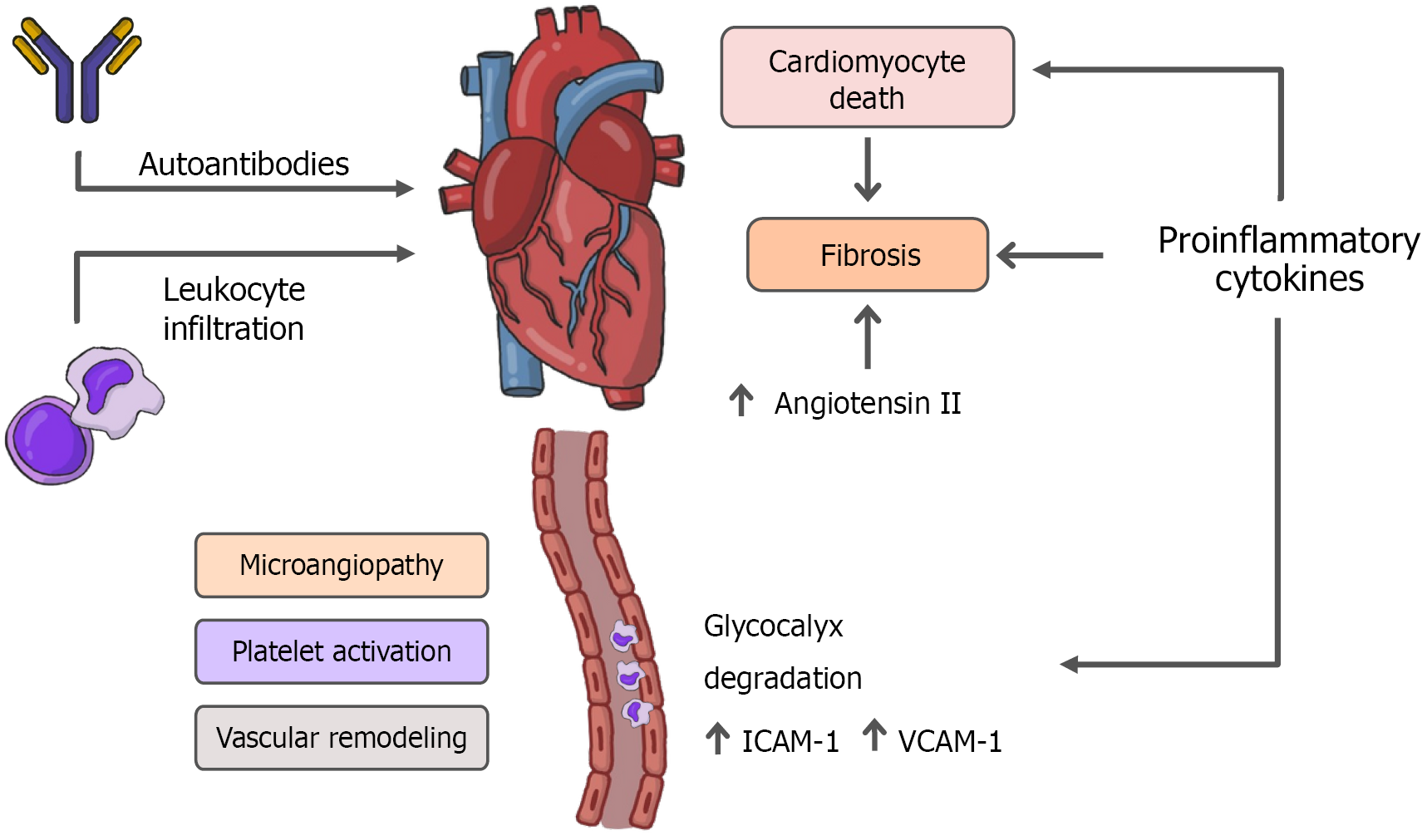

The proposed pathophysiological mechanisms include persistent damage from direct viral invasion of cardiomyocytes and subsequent cell death, endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis, transcriptional alterations in various cardiac cell types, complement activation, complement-mediated coagulopathy and microangiopathy, ACE2 downregulation with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) dysregulation, autonomic dysfunction, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/small mother against decapentaplegic (Smad) signaling pathway activation leading to myocardial fibrosis and tissue remodeling[20-24]. Furthermore, persistent immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, and viral persistence in immune-privileged sites are also suggested as potential contributors to extrapulmonary LC, including cardiovascular involvement[20,21]. Figure 1 summarizes the main pathophysiological mechanisms proposed in LC, which collectively contribute to clinical manifestations such as chest pain, arrhythmias, exercise intolerance, and autonomic symptoms.

In LC, persistent inflammation is widely recognized as one of the main mechanisms underlying prolonged cardiovascular manifestations, such as chest pain, palpitations, diastolic dysfunction, and subclinical myocarditis. SARS-CoV-2 infection can activate a dysregulated immune response, in which inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) play crucial roles. IL-6 promotes endothelial activation, stimulates the production of acute phase proteins, and contributes to cardiac remodeling, while TNF-α has direct cardiotoxic effects, such as mitochondrial dysfunction and induction of cardiomyocyte apoptosis[25,26].

Therefore, the persistence of these inflammatory mediators after the acute phase may lead to the maintenance of a chronic pro-inflammatory state, even in previously healthy individuals and/or those without comorbidities. Addi

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging evidence in COVID-19 survivors revealed persistent signs of myocardial inflammation, with lymphocytic infiltration and interstitial fibrosis weeks to months after acute infection, even in mild or asymptomatic cases[29]. This cellular infiltration, predominantly of T cells and macrophages, compromises the structural and functional integrity of the myocardium, favoring electrophysiological changes and reduced contractile function.

SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with the induction of a dysregulated systemic inflammatory response, whose intensity and persistence play a central role in the endothelial damage observed in acute COVID-19 and LC. The activation of the inflammasome, in response to viral detection, promotes the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18, in addition to favoring inflammatory cell death mechanisms, such as pyroptosis, resulting in direct impairment of endothelial integrity[30-32].

This damage is amplified by the degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx, a network of proteoglycans and glyco

Consequently, there is an increase in the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, which promote leukocyte adhesion to the vascular wall and facilitate their transmigration into tissues, amplifying the local inflammatory infiltrate[36]. These changes sustain low-grade chronic inflammation and promote a dysfunctional endothelial environment, conducive to platelet activation, micro

The initial incident that activates the fibrogenic signaling pathway is usually myocardial cell death. However, SARS-CoV-2 can also induce myocardial fibrosis through pathways that are not dependent on cardiomyocyte death, such as dangerous stimulating factors and myocardial inflammation[38]. Through these pathways, the virus triggers cardiac fibrosis, characterized by the activation of cardiac fibroblasts[39] and collagen deposition[40] by multiple mechanisms.

An essential mechanism for fibroblast activation is the dysregulation of the RAAS, a hormonal system that regulates cardiovascular functions through enzymes and bioactive peptides[41]. Renin converts angiotensinogen into angiotensin I, which is transformed by ACE into angiotensin II (Ang II), the main effector of the system. Ang II acts mainly on Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and Ang II type 2 receptor, with relevant effects on homeostasis and cardiovascular pathology[42,43].

By binding to AT1R, Ang II activates the intracellular mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways. This activation results in the phosphorylation of Smad2/3 and the formation of a complex with Smad4, which translocates to the nucleus and induces the expression of fibrogenic genes, such as TGF-β, fibronectin, and procollagen I. Consequently, fibroblasts are activated and extracellular matrix accumulates, promoting cardiac fibrosis[44-47].

SARS-CoV-2 infection reduces the expression of ACE2, which normally degrades Ang II. This downregulation leads to the accumulation of circulating Ang II, intensifying the activation of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis[48]. Even without an increase in renin, this imbalance promotes inflammation, fibrosis, and cardiovascular dysfunction, factors observed in diseases such as myocarditis and heart failure.

Taken together, these mechanisms are interconnected processes that sustain the cardiovascular manifestations of LC. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α not only drive direct myocardial injury but also prime the vascular endothelium for dysfunction. Endothelial activation, glycocalyx degradation, and microthrombosis perpetuate hypoxia and amplify local inflammatory responses, thereby reinforcing immune dysregulation. In this pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic milieu, fibroblast activation is maintained by RAAS imbalance and TGF-β/Smad signaling, leading to progressive extracellular matrix deposition and cardiac remodeling. These mechanisms do not act in isolation but rather form a self-reinforcing cycle of injury and repair that explains the chronicity of cardiovascular symptoms in LC, even after viral clearance.

Patients with LC exhibited a range of cardiovascular manifestations, including dyspnea[49,50], chest discomfort[50], palpitations[51], dizziness[52], and tachycardia[53]. Cardiovascular complications can manifest several weeks after acute infection and most frequently include coronary artery disease, tachycardia, systemic arterial hypertension, acute heart failure, and myocardial damage. Cases of fulminant myocarditis, pericarditis, and cor pulmonale have also been reported. The most commonly presented symptoms are palpitations, dyspnea, chest pain, dizziness, pre-syncope, or syncope, which may be triggered by physical exertion and emotional stress[4,54].

Fatigue ranks among the most frequently reported symptoms in post-COVID cases, with prevalence rates ranging from approximately 17.5% to 72% of patients[55,56]. In this context, Liang et al[57] found a higher rate of fatigue (60%) for patients who were hospitalized due to COVID-19 infection in wards or in intensive care units three months after dis

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examined nearly 10 million patients, from 8 cohort studies, four weeks or more after COVID-19 infection, and found an increased risk of new-onset cardiovascular diseases. The study demon

Acute SARS-CoV-2 infections can cause myocarditis and pericarditis[63-65]. Notably, the persistence of inflammation in these tissues is evident in a significant proportion of patients who have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection[29]. A study using cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) to follow patients who recovered from COVID-19 revealed myocardial injury in 30% of the study group, with some follow-ups reflecting fibrosis and tissue necrosis[66]. Another study with athletes without obvious risk of cardiovascular disease but who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 showed that 15% had myocardial damage suggestive of myocarditis[67].

Inflammation of cardiac tissue in COVID-19 cases is classified as a chronic lesion, therefore examinations, such as CMR and endocardial biopsy, are the main methods of diagnostic evaluation[68,69]. The Lake Louise criteria are employed to diagnose myocarditis via CMR and require at least one T1-based criterion (indicating fibrosis or damage) and one T2-based criterion (indicating edema or inflammation)[68,70]. In post-COVID myocarditis, T1-based criteria are especially prevalent[71].

Despite the documentation of various pathological rhythms, such as ventricular tachycardia, atrioventricular block, and atrial fibrillation, in patients with acute conditions[72], few studies have been conducted on arrhythmias in LC. However, given the knowledge about the rhythmic consequences of myocardial damage, it is necessary to monitor the rhythmic evolution of patients, especially those identified with cardiovascular sequelae[73]. The documentation of tachycardia, palpitations, and arrhythmias as manifestations of prolonged symptoms in patients recovered from COVID-19[74] may be associated with the mechanism of dysautonomia generated by the infection[75-77], since neurotropism and involve

Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in severe pneumonia cases, is associated with ventricular dysfunction and remodeling, with the right ventricle usually being the most affected[79]. These abnormalities are associated with a poorer prognosis and higher mortality rate[79-81]. However, this dysfunction does not seem to be related only to the acute phase, since a study conducted with a group of patients 3 months after hospitalization for COVID-19 reported slightly reduced right ventricular function and diastolic dysfunction twice as frequent as in the control group[82]. Another cross-sectional study conducted one year after hospital discharge found that 11 patients (2.0%) had onset of heart failure and another seven, already diagnosed with chronic heart failure, had to intensify treatment after infection[83].

In order to determine whether ventricular remodeling resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection is transient or permanent, a longitudinal study was conducted with a 3-month follow-up after hospitalization, which showed the persistence of remodeling in almost one-third of the study population[84]. Many patients continue to exhibit changes in myocardial function due to a reduction in global longitudinal strain of the left ventricle, but with subclinical findings, i.e., without clinical cardiac findings[85].

Patients with COVID-19, especially those admitted to intensive care units, are more likely to develop arterial or venous thromboembolism[86]. A prospective, multicenter, 12-month follow-up cohort study comparing patients discharged from hospital due to COVID-19 with a group discharged for other causes found thrombotic events to be one of the most significant long-term sequelae[87]. Additionally, a cross-sectional study showed deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism were among the most prevalent complications one year after acute infection[83].

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein directly interacts with platelets and fibrinogen, promoting the formation of amyloid fibrin microclots resistant to fibrinolysis. These microclots, along with hyperactivated platelets, trap pro-inflammatory mole

Among the main autonomic dysfunctions described in LC are: Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), inappropriate sinus tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, vasovagal syncope and chronotropic incompetence[89]. Notably, POTS, a multisystemic autonomic dysregulation that occurs upon standing, emerges as one of the autonomic dysfunctions with the most prevalent symptoms in LC[58,90] and has several possible causes, such as hypovolemia, neuropathy, autoimmunity, and neuroendocrine dysfunction[91]. SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be closely associated with autoimmune phenomena, through molecular mimicry with components of the nervous system, and direct cellular toxicity[92]. Endothelial dysfunction also contributes to dysautonomia, since reduced production of vasoactive (endothelin) and vasodilator (nitric oxide) substances compromises fine adjustment of blood pressure and heart rate by desensitizing baroreceptors, for example[93,94].

As the clinical manifestations of LC become better understood and more extensively studied, a significant similarity has been observed with other syndromes that also present cardiovascular symptoms, particularly those associated with chronic conditions following viral infections, also known as post-viral syndromes[95], such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)[96-98] and dysautonomia, including POTS[58].

Following this context, the present findings on LC can be better understood when placed in the context of other post-viral syndromes. Data reports suggest that survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) frequently experienced persistent fatigue, diffuse myalgia, weakness, depression, and non-restorative sleep, with substantial overlap with the clinical features of ME/CFS and fibromyalgia[96], highlighting the fact that LC may be a part of a spectrum of post-viral conditions.

Moreover, overlaps are further supported by evidence from LC cohorts, which consistently describe core symptoms such as profound fatigue, PEM, non-restorative sleep, and cognitive dysfunction, strongly paralleling the clinical picture of ME/CFS[58]. As in fibromyalgia, patients also report diffuse musculoskeletal pain, although in LC this tends to be less prominent than fatigue and neurocognitive complaints, resembling the profile observed in post-SARS syndrome[96]. Finally, non-restorative sleep was also a key complaint in both SARS survivors and LC patients, supporting the notion that sleep disturbance is a recurrent feature across post-viral syndromes[58,96].

A 2023 study investigated long-term symptoms and biomarkers in patients with LC, particularly those who developed ME/CFS. Key findings revealed that patients meeting the Canadian Consensus Criteria for ME/CFS experienced persistently severe symptoms, including fatigue, PEM, and autonomic dysfunction, even 20 months post-infection, with biomarkers such as reduced hand grip strength showing significant correlation with worse long-term outcomes, thereby suggesting its potential role as a prognostic tool[99].

Taken together, these findings indicate that while LC shares central features with other post-viral syndromes, its frequent association with both exertional intolerance and cognitive dysfunction suggests a broader clinical profile[58]. The variability of manifestations emphasizes the uniqueness of LC and illustrates why establishing standardized diagnostic criteria remains particularly challenging. Table 1 shows major cardiovascular biomarkers in LC, the type of dysfunction they reflect, how often they are altered, and what they may indicate for patient care.

| Ref. | Biomarker | Category | Alteration in long coronavirus disease | Potential clinical utility |

| [29,106,107] | Troponins | Myocardial injury | Persistent elevated levels for up to 6 months in 15%-30% of patients, even without clinical heart failure symptoms | Indication of subclinical myocardial injury; associated with MACE and poorer prognosis |

| [112,118,119] | NT-proBNP/BNP | Hemodynamic stress | Elevated in approximately 11% of LC cases; levels around 1000 pg/mL predictive of mortality | Predictor of MACE and mortality |

| [112,124,125] | D-dimer | Coagulation activation | Elevated in approximately 20% of LC cases | Indicates thromboembolic risk and ongoing vascular inflammation |

| [132-134] | IL-6 | Systemic inflammation | Elevated in approximately 48% of recovered patients; association with cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction | Marker of sustained inflammation |

| [136] | CRP | Chronic inflammation | Frequently elevated in symptomatic patients; paradoxically, low levels (≤ 3 mg/L) associated with CMR abnormalities | Assessment of cardiovascular risk and chronic inflammation |

| [139] | Ferritin | Inflammation; iron storage | Elevated up to 12 months in LC patients | Assessment of cardiovascular risk and persistent inflammation |

| [145,146] | vWF (Ag)/ADAMTS13 | Endothelial dysfunction; thrombosis | Ratio ≥ 1.5 in approximately 33% of patients; correlated with desaturation and exercise intolerance | Indicates prothrombotic state and endothelial injury |

| [134,147] | ET-1 | Vascular dysfunction | Elevated up to 3 months post-infection; persists in symptomatic individuals | Suggests microvascular dysfunction |

Cardiac troponins I and T are intracellular proteins involved in cardiomyocyte contraction. Their presence in the blood circulation indicates myocardial lesion[100], commonly associated with myocardial infarction. Serological troponin levels start to increase within 3-6 hours of heart injury, peak by 12-24 hours, and remain elevated for 7-14 days[101]. High-sensitivity troponin assays can detect concentrations as low as 5 ng/L, with the diagnostic cutoff typically around 14 ng/L, though this varies by assay manufacturer[102]; thus, levels above this threshold in a clinical context of ischemia confirm myocardial infarction[101]. Elevated troponins are also used for stratifying cardiovascular risk and predicting future cardiovascular events[100,103], even for patients with no conventional risk factors[104,105].

In patients who survived hospitalization for COVID-19, elevated troponin levels have been identified as a biomarker associated with increased all-cause death during follow-up, as well as a higher likelihood of presenting cardiovascular symptoms, such as fatigue and dyspnea (57.7% and 62.8%, respectively)[106]. Additionally, Fiedler et al[107] demon

Puntmann et al[29] reported that 15% to 30% of former severe COVID-19 patients from the University Hospital Frankfurt exhibited mildly elevated troponin I levels (0.04-0.15 ng/mL) for up to three to six months post-discharge, even in the absence of clinical signs of heart failure. These authors also observed a correlation between elevated troponin T levels and late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, even in patients with mild symptoms, suggesting persistent myocardial damage, which may predispose these individuals to long-term cardiovascular complications[29]. Thus, elevated troponin levels may aid in cardiovascular risk stratification as well as in guiding further cardiac imaging investigations (e.g., CMR). Additionally, these findings reinforce the prognostic value of troponin; however, studies are heterogeneous in terms of population, timing, and assays. The prognostic significance of small chronic elevations remains uncertain. Longitudinal studies that correlate persistent troponin levels with clinical outcomes are needed to strengthen its clinical utility.

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and its inactive cleavage product N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) are secreted by ventricular myocytes in response to mechanical stretch caused by volume or pressure overload, reflecting hemodynamic stress[109]. Serological BNP > 100 pg/mL or NT-proBNP > 300 pg/mL values are used to support heart failure diagnosis and differentiate it from pulmonary causes of dyspnea[110]. Although significantly useful and utilized, specificity may be limited, especially considering factors such as age and renal function[111], highlighting the importance of a careful analysis paired with other clinical parameters, in order to better correlate the results with heart failure severity, guide therapy strategies, monitor treatment response and decompensation[110].

NT-proBNP is elevated in approximately 11% of LC cases[112]. It is well established that elevated NT-proBNP levels are associated with an increased risk of MACE in patients with COVID-19[113-117]. According to Sabanoglu et al[118], NT-proBNP levels close to 1000 pg/mL demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity for predicting mortality, both during hospitalization and in one-year long-term follow-up. Furthermore, evidence suggests that NT-proBNP, when assessed alongside hs-TnI, serves as a significant clinical parameter for identifying patients at higher cardiovascular risk and with poorer prognosis during and after COVID-19 infection. This combination aids in clinical decision-making, enabling early and individualized management of these patients[118].

According to Sarıçam et al[119], elevated pro-BNP levels combined with reduced nitric oxide levels were associated with symptomatic post-COVID patients compared to asymptomatic individuals. Such patients presented symptoms including palpitations, effort-related fatigue, and, in electrocardiographic evaluations, resting sinus tachycardia or atrial tachycardia recorded on 24-hour Holter monitoring[119].

In this context, NT-proBNP has prognostic value for identifying hemodynamic overload or increased risk of cardiac events. However, reported prevalences in LC are moderate, and optimal cutoffs are not yet well established, as its specificity is limited by factors such as age and renal function. This highlights the need for prospective studies validating age- and renal function-adjusted thresholds. Moreover, evidence suggests improved clinical performance when NT-proBNP is combined with other biomarkers, such as troponin.

D-dimer is a fibrin degradation product that indicates active coagulation and fibrinolysis. Since it is highly sensitive but poorly specific for venous thromboembolism, a low result is useful for excluding the diagnosis, but a high result does not confirm it[120]. Elevated D-dimer has also been linked to an increase in-hospital and long-term cardiovascular complications for patients with acute coronary syndrome[121]. While the conventional threshold for D-dimer is < 500 ng/mL, it is usually age-adjusted for patients over 50 years old, according to the formula “age × 10 ng/mL”[122]. When used in assessment of cardiac risk, there is no universally accepted value, ranging from 210 to 1000 ng/mL[122,123].

This biomarker is elevated in approximately 20% of LC cases[112]. A meta-analysis conducted by Yong et al[124] demonstrated that D-dimer levels are significantly higher in COVID-19 survivors with LC compared to those without the syndrome, with a small to moderate effect size (standardized mean difference = 0.27; 95% confidence interval: 0.09-0.46; P < 0.01), indicating prolonged involvement of coagulation activation in LC pathophysiology. Additional evidence suggests that thrombo-inflammation, mediated by endothelial activation [with elevated von Willebrand factor (vWF)], platelet activation, and neutrophil extracellular trap formation, leads to a hypercoagulable state characterized by increased D-dimer levels, contributing to vascular complications observed in LC[125].

Although nonspecific, D-dimer indicates fibrinolytic activation, and its values are influenced by factors such as age and comorbidities, warranting caution in interpretation. Persistently elevated levels in LC suggest chronic thrombo-inflammation, which should prompt targeted evaluation for active thrombosis and vigilance for vascular complications. However, these findings do not define when treatment should be initiated, making it crucial to correlate D-dimer levels with clinical and imaging findings.

IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that promotes hepatic synthesis of C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute-inflammation marker. Both IL-6 and high-sensitivity CRP baseline levels have been linked to atherosclerosis and MACE, reflecting systemic inflammation linked to plaque instability[126,127], and CRP > 3 mg/L shows correlation with high cardiova

Several studies have shown that, during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, elevated IL-6 and IL-10 levels are strongly associated with severe disease progression, demonstrating significant predictive value[131]. In the context of LC, multiple research groups have reported persistently elevated IL-6 levels among patients with ongoing symptoms[132]. Notably, Jatiya et al[133] found that elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers, including IL-6 and CRP, measured three months post-infection, were significantly associated with the presence and severity of cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction. Furthermore, Willems et al[134] observed that patients recovered from acute COVID-19 continued to exhibit elevated and persistent levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-18 (73.9%), IL-6 (47.7%), and IL-1RA (48.9%), three months post-infection, indicating sustained vascular inflammation.

CRP levels frequently remain elevated in LC patients, particularly in those with cardiovascular symptoms, which has been linked to endothelial activation and a persistent thrombo-inflammatory state[135]. However, in a study by Roca-Fernandez et al[136], lower CRP levels (≤ 3 mg/L) measured six months after COVID-19 were unexpectedly identified as significant predictors of CMR abnormalities at 12 months post-infection. IL-6 and CRP have shown associations with an increased risk of adverse outcomes, but their interpretation is complicated by phenotypic heterogeneity and paradoxical findings. In this context, standardization of sampling timing and studies testing biomarker-guided anti-inflammatory interventions are needed to evaluate their impact on clinical outcomes.

During the acute phase of COVID-19, elevated ferritin levels have been correlated with poor prognosis and are considered predictive of clinical deterioration[137,138]. In LC, Poyatos et al[139] reported that patients with LC exhibited persistently elevated levels of troponin, NT-proBNP, and ferritin, biomarkers associated with cardiovascular risk and systemic inflammation, for up to 12 months post-infection. Additionally, ferritin levels showed an inverse correlation with the mobilization of endothelial colony-forming cells, indicating that chronic inflammation may impair vascular repair mechanisms[139].

Both atherosclerosis and thrombosis are strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction, which can lead to the liberation of important mediators. For example, serological vWF, a glycoprotein involved in platelet adhesion, is linked to increased cardiovascular risk[140] and could be useful in the evaluation of heart valve disease[141], although its clinical impact might still be low[142]. Another important endothelial factor is endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent vasoconstrictor peptide that is elevated in heart failure and hypertension. Higher ET-1 may be useful in predicting hospitalization and mortality, but due to assay variability, it is not routinely used[143]. The adhesive activity of vWF multimers is regulated by a specific metalloprotease, ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motifs, member 13). There is growing evidence that interactions between neutrophil extracellular traps and vWF contribute to arterial and venous thrombosis, as well as inflammation[144].

Prasannan et al[145] demonstrated that an imbalance in the vWF antigen to ADAMTS13 ratio [vWF (Ag)/ADAMTS13], specifically an elevated ratio (≥ 1.5), is present in approximately one-third of patients with LC and is strongly associated with reduced physical capacity in these patients, evidenced by significant oxygen desaturation (≥ 3%) and/or increased lactate levels following exercise tests. Moreover, a persistently elevated vWF (Ag)/ADAMTS13 ratio is linked to a prothrombotic state and endothelial dysfunction, suggesting that microthrombi in capillaries of large muscles and possibly other vascular beds may cause functional limitation, exercise intolerance, and fatigue, common symptoms of LC that may reflect cardiovascular sequelae[145,146]. However, analytical variability and the lack of validated cut-off values limit the routine use of these biomarkers.

Willems et al[134] showed that ET-1 levels are significantly elevated not only during the acute phase of COVID-19 but also up to three months after recovery, indicating ongoing endothelial involvement, which may contribute to persistent cardiovascular manifestations[147]. Although direct clinical studies are still limited, the finding of elevated ET-1 suggests that vascular mechanisms potentially related to dysautonomia or microvascular ischemia are active in LC. In addition, Turgunova et al[148] reported that elevated ET-1 levels during acute COVID-19 were associated with increased 30-day mortality. However, this association did not persist at 12 months, indicating that ET-1 is a promising marker of early mortality, although data on the prediction of long-term outcomes remain inconsistent. Multicenter studies correlating endothelial biomarkers with clinical outcomes are warranted.

Growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) is a member of the TGF-β superfamily and is upregulated in response to oxidative stress, inflammation, and myocardial strain[149]. It has been shown to independently predict mortality by cardiovascular events, and hospitalization for heart failure[150], normal levels are typically < 1200 pg/mL, and elevated levels (> 1800 pg/mL) suggest worse prognosis[151]. Bu et al[152] showed that GDF-15 serves as a biomarker of COVID-19 severity, being useful to identify individuals at high risk of progression to severe disease. In this context, Ono et al[153] demonstrated that elevated GDF-15 levels during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly predict persistent symptoms, including fatigue, decreased concentration, and pain, three months post-infection in non-hospitalized patients. Furthermore, Ishak et al[154] reported that serum GDF-15 levels were significantly higher in pediatric COVID-19 patients compared to controls, and that those with cardiac manifestations exhibited significantly higher GDF-15 levels than those without such manifestations. This biomarker is promising due to its potential to identify, at an early stage, patients at higher risk of unfavorable outcomes and prolonged manifestations of COVID-19. However, its elevation may reflect different conditions, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, or cardiac overload, which limits its utility as a standalone clinical marker.

Galectin-3 is a β-galactoside-binding lectin secreted by activated macrophages, contributing to cardiac fibrosis and inflammation. Levels > 17.8 ng/mL are considered elevated and associated with increased mortality and re-hospitalization in heart failure patients[155]. Data suggest that galectin-3 could serve as a biomarker for risk stratification in children undergoing cardiac surgery, with heart failure or Kawasaki disease[156], and also used for detection of early stage cardiac pathologies in adults[157]. In the context of LC, galectin-3 may play an important predictive role, although its evaluation must be performed cautiously to avoid misinterpretation[158]. Portacci et al[159] demonstrated that galectin-3 shows a significant, albeit modest, association with the development of LC when assessed between 60 and 120 days after infection, indicating notable predictive value. However, due to its time-dependent nature and the limited performance of current statistical models, further studies are required to validate its routine clinical use[159]. Moreover, galectin-3 has been shown to correlate with clinical severity as assessed by the sequential organ failure assessment score: In patients with acute respiratory diseases, galectin-3 may serve not only as a marker of disease severity but also of heightened hypercoagulability, as evidenced by platelet activation markers and increased thrombogenicity markers[160].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs (approximately 22 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally[161], and have an emerging role as biomarkers for different clinical conditions. Circulating miRNAs such as miR-1, miR-208a, and miR-499 have shown high specificity for myocardial injury[162]. Although not yet used clinically due to lack of assay standardization and high cost[163], investigation of miRNAs as clinical indicators is on the rise. In this context, Gao et al[164] demonstrated that the 2’,5’-oligoadenylate synthetase gene family is significantly overexpressed in SARS-CoV-2-infected cardiomyocytes and in cardiac tissues with heart failure. These genes act as mediators in the progression of COVID-19 associated heart failure. Moreover, the authors identified differential expression of several miRNAs associated with these genes[164,165], suggesting their potential role as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in COVID-19-related cardiac injury. Thus, the high specificity of these biomarkers is promising, as they may offer greater precision in diagnosing subclinical cardiac dysfunction and in differentiating viral inflammation from structural damage. However, their limited cost-effectiveness and the requirement for advanced technology currently restrict their routine clinical application.

Despite promising associations, several gaps still limit the translation of biomarkers into clinical practice. First, there is no consensus on the standardization of assays or the reference ranges used in studies of candidate markers. In addition, evidence linking specific biomarker trajectories to clinically meaningful outcomes, such as MACE, arrhythmias, or heart failure, remains scarce, and no validated clinical models are currently available to guide practice. The clinical applicability of many biomarkers also remains uncertain, as it is not yet clear which management strategies should follow a positive result, whether therapeutic intensification, advanced imaging, or closer surveillance. These gaps hinder both the development of specific guidelines and the integration of biomarkers into routine care pathways.

Furthermore, issues of cost-effectiveness and accessibility across different levels of healthcare represent major challenges to the implementation of biomarkers in clinical practice. High-cost assays (omics panels, circulating miRNAs, and specialized endothelial markers) and advanced imaging (such as CMR) are feasible primarily in tertiary centers and high-income health systems, whereas primary care and resource-limited settings must often rely on inexpensive, widely available tests (e.g., troponin, D-dimer, CRP). Much remains to be understood regarding how these biomarkers behave, their relationship with persistent symptoms, and their potential role in predicting and monitoring the specific cardio

Thus, LC presents a new scenario for the application and study of biomarkers, which may contribute to a more targeted and personalized approach in patient management. These methodological and economic gaps help explain why, despite growing scientific interest, biomarkers are not yet routinely applied for screening, diagnosis, or monitoring of cardiovascular LC. Assay harmonization, prospective longitudinal cohorts with prespecified clinical endpoints, and cost-effectiveness analyses across diverse health systems are essential to move biomarkers from research into clinical practice.

The rising incidence of cardiovascular manifestations in LC highlights the urgent need for innovation in diagnosis and treatment. Among the most promising areas of research is the identification and validation of cardiovascular biomarkers. A specific set of candidate biomarkers should be prioritized for validation in well-defined prospective cohorts. These biomarkers are: Those indicating cardiac injury (such as high-sensitivity troponin), markers of hemodynamic stress (such as NT-proBNP), coagulation and endothelial dysfunction markers (such as D-dimer and the vWF/ADAMTS13 ratio), systemic inflammation markers (such as IL-6 and CRP), fibrosis-associated markers (such as galectin-3 and GDF-15), and certain circulating nucleic acids (such as miRNA panels and cell-free DNA) that capture immune response and myocardial remodeling signals.

In addition, secondary candidates that may be assessed alongside these include ET-1, oxidative stress markers, and autoantibody profiles. The selection of biomarkers should consider: (1) Biological plausibility linking the marker to cardiovascular mechanisms of LC; (2) Analytical reproducibility across different laboratories; and (3) Preliminary evidence of association with clinical or imaging outcomes. Whenever possible, assays chosen for multicenter studies should have validated performance characteristics, clearly defined pre-analytical protocols, and accessible reference ranges to facilitate pooled analyses and meta-analyses. Robust longitudinal studies involving well-matched patient cohorts and extended follow-up are essential to establish their clinical value and enable personalized interventions.

Simultaneously, the immunological mechanisms underlying LC cardiovascular complications require further clarifi

The main therapeutic approaches for LC, particularly in cases with cardiovascular involvement, require more careful evaluation. Anti-inflammatory strategies, such as IL-6 inhibitors or selective immunomodulators, should have potential for patients with persistent inflammation, but controlled trials with rigorous safety monitoring are essential. Antifibrotic approaches, including therapies targeting the TGF-β pathway or drugs repurposed from fibrotic diseases, may benefit patients with progressive fibrosis and elevated galectin-3/GDF-15 levels; however, they often require prolonged treatment and validation of cardiovascular safety. Adaptive trials using intermediate imaging endpoints can be valuable in this context. Antithrombotic strategies should be limited to patients with persistent coagulation activation and require biomarker-guided trials to balance efficacy against bleeding risk. Additionally, autonomic modulation, including rehabilitation, neuromodulation, or pharmacologic therapies, should be considered for patients with confirmed dysfunction, using objective functional and autonomic outcomes.

Finally, comprehensive clinical surveillance strategies must be established to monitor long-term cardiovascular changes, such as arrhythmias, ventricular remodeling, and autonomic dysfunction. Structured follow-up protocols that incorporate clinical, imaging, and biomarker data will be essential for the early detection of subclinical abnormalities, especially in high-risk populations. Personalized care, based on detailed risk stratification, and supported by advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, could enable more accurate predictions of disease progression and guide individualized treatment plans. This combined approach, linking systematic monitoring, precision medicine, and technological innovation, represents a critical step toward improving cardiovascular care in the context of LC.

In summary, due to the heterogeneity of LC manifestations, conventional diagnostics often fail to detect subtle or evolving impairments. Thus, the evaluation of well-established cardiac biomarkers and emerging indicators offers a promising approach for early detection, risk stratification, and individualized management of patients with this condition. However, the clinical application of these biomarkers remains incipient due to study heterogeneity, lack of assay standardization, and incomplete longitudinal validation. Therefore, there is an urgent need for future research to evaluate, in large cohorts with prolonged follow-up and matched control groups, clinical correlations between stan

| 1. | Zaidi AK, Dehgani-Mobaraki P. Long Covid. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2024;202:113-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102-e107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 1672] [Article Influence: 418.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | CDC. Long COVID Basics. Jul 24, 2025. [cited 27 Jul 2025]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/long-covid/about/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcovid%2Flong-term-effects%2Findex.html. |

| 4. | Dieter RS, Kempaiah P, Dieter EG, Alcazar A, Tafur A, Gerotziafas G, Gonzalez Ochoa A, Abdesselem S, Biller J, Kipshidze N, Vandreden P, Guerrini M, Dieter RA Jr, Durvasula R, Singh M, Fareed J. Cardiovascular Symposium on Perspectives in Long COVID. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2025;31:10760296251319963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Feb 26, 2025. [cited 20 Jun 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-covid-19-condition-(long-covid). |

| 6. | Muthuka JK, Nzioki JM, Kelly JO, Musangi EN, Chebungei LC, Nabaweesi R, Kiptoo MK. Prevalence and Predictors of Long COVID-19 and the Average Time to Diagnosis in the General Population: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. COVID. 2024;4:968-981. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Hall JP, Kurth NK, McCorkell L, Goddard KS. Long COVID Among People With Preexisting Disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2024;114:1261-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kusumawardhani NY, Putra ICS, Kamarullah W, Afrianti R, Pramudyo M, Iqbal M, Prameswari HS, Achmad C, Tiksnadi BB, Akbar MR. Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology and Diagnosis Approach. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2023;24:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang LW, Li HM, He B, Wang XB, Zhang QZ, Peng WX. Prevalence of cardiovascular symptoms in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2025;23:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parotto M, Gyöngyösi M, Howe K, Myatra SN, Ranzani O, Shankar-Hari M, Herridge MS. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: understanding and addressing the burden of multisystem manifestations. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:739-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singh TK, Zidar DA, McCrae K, Highland KB, Englund K, Cameron SJ, Chung MK. A Post-Pandemic Enigma: The Cardiovascular Impact of Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. Circ Res. 2023;132:1358-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mukkawar RV, Reddy H, Rathod N, Kumar S, Acharya S. The Long-Term Cardiovascular Impact of COVID-19: Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Management. Cureus. 2024;16:e66554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Erlandson KM, Geng LN, Selvaggi CA, Thaweethai T, Chen P, Erdmann NB, Goldman JD, Henrich TJ, Hornig M, Karlson EW, Katz SD, Kim C, Cribbs SK, Laiyemo AO, Letts R, Lin JY, Marathe J, Parthasarathy S, Patterson TF, Taylor BD, Duffy ER, Haack M, Julg B, Maranga G, Hernandez C, Singer NG, Han J, Pemu P, Brim H, Ashktorab H, Charney AW, Wisnivesky J, Lin JJ, Chu HY, Go M, Singh U, Levitan EB, Goepfert PA, Nikolich JŽ, Hsu H, Peluso MJ, Kelly JD, Okumura MJ, Flaherman VJ, Quigley JG, Krishnan JA, Scholand MB, Hess R, Metz TD, Costantine MM, Rouse DJ, Taylor BS, Goldberg MP, Marshall GD, Wood J, Warren D, Horwitz L, Foulkes AS, McComsey GA; RECOVER-Adult Cohort. Differentiation of Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Postacute Sequelae by Standard Clinical Laboratory Measurements in the RECOVER Cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177:1209-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parums DV. Long COVID or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC) and the Urgent Need to Identify Diagnostic Biomarkers and Risk Factors. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e946512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bakhshandeh B, Sorboni SG, Javanmard AR, Mottaghi SS, Mehrabi MR, Sorouri F, Abbasi A, Jahanafrooz Z. Variants in ACE2; potential influences on virus infection and COVID-19 severity. Infect Genet Evol. 2021;90:104773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Möhlendick B, Schönfelder K, Breuckmann K, Elsner C, Babel N, Balfanz P, Dahl E, Dreher M, Fistera D, Herbstreit F, Hölzer B, Koch M, Kohnle M, Marx N, Risse J, Schmidt K, Skrzypczyk S, Sutharsan S, Taube C, Westhoff TH, Jöckel KH, Dittmer U, Siffert W, Kribben A. ACE2 polymorphism and susceptibility for SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of COVID-19. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2021;31:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gallagher TM, Buchmeier MJ. Coronavirus spike proteins in viral entry and pathogenesis. Virology. 2001;279:371-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guney C, Akar F. Epithelial and Endothelial Expressions of ACE2: SARS-CoV-2 Entry Routes. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2021;24:84-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vukusic K, Thorsell A, Muslimovic A, Jonsson M, Dellgren G, Lindahl A, Sandstedt J, Hammarsten O. Overexpression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in cardiomyocytes of failing hearts. Sci Rep. 2022;12:965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chung MK, Zidar DA, Bristow MR, Cameron SJ, Chan T, Harding CV 3rd, Kwon DH, Singh T, Tilton JC, Tsai EJ, Tucker NR, Barnard J, Loscalzo J. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Disease: From Bench to Bedside. Circ Res. 2021;128:1214-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:543-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 917] [Article Influence: 152.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Delorey TM, Ziegler CGK, Heimberg G, Normand R, Yang Y, Segerstolpe Å, Abbondanza D, Fleming SJ, Subramanian A, Montoro DT, Jagadeesh KA, Dey KK, Sen P, Slyper M, Pita-Juárez YH, Phillips D, Biermann J, Bloom-Ackermann Z, Barkas N, Ganna A, Gomez J, Melms JC, Katsyv I, Normandin E, Naderi P, Popov YV, Raju SS, Niezen S, Tsai LT, Siddle KJ, Sud M, Tran VM, Vellarikkal SK, Wang Y, Amir-Zilberstein L, Atri DS, Beechem J, Brook OR, Chen J, Divakar P, Dorceus P, Engreitz JM, Essene A, Fitzgerald DM, Fropf R, Gazal S, Gould J, Grzyb J, Harvey T, Hecht J, Hether T, Jané-Valbuena J, Leney-Greene M, Ma H, McCabe C, McLoughlin DE, Miller EM, Muus C, Niemi M, Padera R, Pan L, Pant D, Pe'er C, Pfiffner-Borges J, Pinto CJ, Plaisted J, Reeves J, Ross M, Rudy M, Rueckert EH, Siciliano M, Sturm A, Todres E, Waghray A, Warren S, Zhang S, Zollinger DR, Cosimi L, Gupta RM, Hacohen N, Hibshoosh H, Hide W, Price AL, Rajagopal J, Tata PR, Riedel S, Szabo G, Tickle TL, Ellinor PT, Hung D, Sabeti PC, Novak R, Rogers R, Ingber DE, Jiang ZG, Juric D, Babadi M, Farhi SL, Izar B, Stone JR, Vlachos IS, Solomon IH, Ashenberg O, Porter CBM, Li B, Shalek AK, Villani AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature. 2021;595:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 590] [Cited by in RCA: 609] [Article Influence: 121.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Song WC, FitzGerald GA. COVID-19, microangiopathy, hemostatic activation, and complement. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3950-3953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, Mehra MR, Schuepbach RA, Ruschitzka F, Moch H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4227] [Cited by in RCA: 4661] [Article Influence: 776.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Gheorghita R, Soldanescu I, Lobiuc A, Caliman Sturdza OA, Filip R, Constantinescu-Bercu A, Dimian M, Mangul S, Covasa M. The knowns and unknowns of long COVID-19: from mechanisms to therapeutical approaches. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1344086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pellicori P, Doolub G, Wong CM, Lee KS, Mangion K, Ahmad M, Berry C, Squire I, Lambiase PD, Lyon A, McConnachie A, Taylor RS, Cleland JG. COVID-19 and its cardiovascular effects: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3:CD013879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | El-Rhermoul FZ, Fedorowski A, Eardley P, Taraborrelli P, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R, Lim PB, Dani M. Autoimmunity in Long Covid and POTS. Oxf Open Immunol. 2023;4:iqad002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cruz T, Albacar N, Ruiz E, Lledo GM, Perea L, Puebla A, Torvisco A, Mendoza N, Marrades P, Sellares J, Agustí A, Viñas O, Sibila O, Faner R. Persistence of dysfunctional immune response 12 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and their relationship with pulmonary sequelae and long COVID. Respir Res. 2025;26:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, Shchendrygina A, Escher F, Vasa-Nicotera M, Zeiher AM, Vehreschild M, Nagel E. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1265-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1240] [Cited by in RCA: 1511] [Article Influence: 251.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 30. | Frisoni P, Neri M, D'Errico S, Alfieri L, Bonuccelli D, Cingolani M, Di Paolo M, Gaudio RM, Lestani M, Marti M, Martelloni M, Moreschi C, Santurro A, Scopetti M, Turriziani O, Zanon M, Scendoni R, Frati P, Fineschi V. Cytokine storm and histopathological findings in 60 cases of COVID-19-related death: from viral load research to immunohistochemical quantification of major players IL-1β, IL-6, IL-15 and TNF-α. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2022;18:4-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li S, Jiang L, Li X, Lin F, Wang Y, Li B, Jiang T, An W, Liu S, Liu H, Xu P, Zhao L, Zhang L, Mu J, Wang H, Kang J, Li Y, Huang L, Zhu C, Zhao S, Lu J, Ji J, Zhao J. Clinical and pathological investigation of patients with severe COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e138070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine Storm. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2255-2273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1324] [Cited by in RCA: 2298] [Article Influence: 383.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Potje SR, Costa TJ, Fraga-Silva TFC, Martins RB, Benatti MN, Almado CEL, de Sá KSG, Bonato VLD, Arruda E, Louzada-Junior P, Oliveira RDR, Zamboni DS, Becari C, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Tostes RC. Heparin prevents in vitro glycocalyx shedding induced by plasma from COVID-19 patients. Life Sci. 2021;276:119376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Targosz-Korecka M, Kubisiak A, Kloska D, Kopacz A, Grochot-Przeczek A, Szymonski M. Endothelial glycocalyx shields the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with ACE2 receptors. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Stahl K, Gronski PA, Kiyan Y, Seeliger B, Bertram A, Pape T, Welte T, Hoeper MM, Haller H, David S. Injury to the Endothelial Glycocalyx in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1178-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tong M, Jiang Y, Xia D, Xiong Y, Zheng Q, Chen F, Zou L, Xiao W, Zhu Y. Elevated Expression of Serum Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules in COVID-19 Patients. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:894-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ebihara T, Matsumoto H, Matsubara T, Togami Y, Nakao S, Matsuura H, Onishi S, Kojima T, Sugihara F, Okuzaki D, Hirata H, Yamamura H, Ogura H. Resistin Associated With Cytokines and Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules Is Related to Worse Outcome in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022;13:830061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:549-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1120] [Cited by in RCA: 1289] [Article Influence: 107.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 39. | Travers JG, Kamal FA, Robbins J, Yutzey KE, Blaxall BC. Cardiac Fibrosis: The Fibroblast Awakens. Circ Res. 2016;118:1021-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 990] [Cited by in RCA: 1285] [Article Influence: 128.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ricard-Blum S, Baffet G, Théret N. Molecular and tissue alterations of collagens in fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2018;68-69:122-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Patel S, Rauf A, Khan H, Abu-Izneid T. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS): The ubiquitous system for homeostasis and pathologies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:317-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82-C97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1315] [Cited by in RCA: 1480] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Xu L, Tan B, Huang D, Yuan M, Li T, Wu M, Ye C. Remdesivir Inhibits Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis in Obstructed Kidneys. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:626510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tian X, Sun C, Wang X, Ma K, Chang Y, Guo Z, Si J. ANO1 regulates cardiac fibrosis via ATI-mediated MAPK pathway. Cell Calcium. 2020;92:102306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Martin ED, Bassi R, Marber MS. p38 MAPK in cardioprotection - are we there yet? Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:2101-2113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wong CKS, Falkenham A, Myers T, Légaré JF. Connective tissue growth factor expression after angiotensin II exposure is dependent on transforming growth factor-β signaling via the canonical Smad-dependent pathway in hypertensive induced myocardial fibrosis. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2018;19:1470320318759358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Khazaal S, Harb J, Rima M, Annweiler C, Wu Y, Cao Z, Abi Khattar Z, Legros C, Kovacic H, Fajloun Z, Sabatier JM. The Pathophysiology of Long COVID throughout the Renin-Angiotensin System. Molecules. 2022;27:2903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S, Flament T, Ferreira-Maldent N, Bruyère F, Stefic K, Gaudy-Graffin C, Grammatico-Guillon L, Bernard L. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:258-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ramadan MS, Bertolino L, Zampino R, Durante-Mangoni E; Monaldi Hospital Cardiovascular Infection Study Group. Cardiac sequelae after coronavirus disease 2019 recovery: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1250-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Romero-Duarte Á, Rivera-Izquierdo M, Guerrero-Fernández de Alba I, Pérez-Contreras M, Fernández-Martínez NF, Ruiz-Montero R, Serrano-Ortiz Á, González-Serna RO, Salcedo-Leal I, Jiménez-Mejías E, Cárdenas-Cruz A. Sequelae, persistent symptomatology and outcomes after COVID-19 hospitalization: the ANCOHVID multicentre 6-month follow-up study. BMC Med. 2021;19:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 52. | Khetpal V, Berkowitz J, Vijayakumar S, Choudhary G, Mukand JA, Rudolph JL, Wu WC, Erqou S. Long-term Cardiovascular Manifestations and Complications of COVID-19: Spectrum and Approach to Diagnosis and Management. R I Med J (2013). 2022;105:16-22. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Dixit NM, Churchill A, Nsair A, Hsu JJ. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome and the cardiovascular system: What is known? Am Heart J Plus. 2021;5:100025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zhang T, Li Z, Mei Q, Walline JH, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Zhu H, Du B. Cardiovascular outcomes in long COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025;12:1450470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID Syndrome: Incidence, Clinical Spectrum, and Challenges for Primary Healthcare Professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021;52:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Simani L, Ramezani M, Darazam IA, Sagharichi M, Aalipour MA, Ghorbani F, Pakdaman H. Prevalence and correlates of chronic fatigue syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder after the outbreak of the COVID-19. J Neurovirol. 2021;27:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Liang L, Yang B, Jiang N, Fu W, He X, Zhou Y, Ma WL, Wang X. Three-month Follow-up Study of Survivors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 after Discharge. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, Redfield S, Austin JP, Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1746] [Article Influence: 349.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Salmon-Ceron D, Slama D, De Broucker T, Karmochkine M, Pavie J, Sorbets E, Etienne N, Batisse D, Spiridon G, Baut VL, Meritet JF, Pichard E, Canouï-Poitrine F; APHP COVID-19 research collaboration. Clinical, virological and imaging profile in patients with prolonged forms of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. J Infect. 2021;82:e1-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Le Bot A, Hamon A, Gouze H, Doucet L, Berkani S, Oliosi E, Mallart E, Corre F, Zarrouk V, Moyer JD, Galy A, Honsel V, Fantin B, Nguyen Y. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e4-e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 113.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Bozkurt B, Das SR, Addison D, Gupta A, Jneid H, Khan SS, Koromia GA, Kulkarni PA, LaPoint K, Lewis EF, Michos ED, Peterson PN, Turagam MK, Wang TY, Yancy CW. 2022 AHA/ACC Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular and Noncardiovascular Complications of COVID-19: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15:e000111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Chippa V, Aleem A, Anjum F. Postacute Coronavirus (COVID-19) Syndrome. 2024 Mar 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Irabien-Ortiz Á, Carreras-Mora J, Sionis A, Pàmies J, Montiel J, Tauron M. Fulminant myocarditis due to COVID-19. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020;73:503-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Hua A, O'Gallagher K, Sado D, Byrne J. Life-threatening cardiac tamponade complicating myo-pericarditis in COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis treated with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 94.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wang H, Li R, Zhou Z, Jiang H, Yan Z, Tao X, Li H, Xu L. Cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients: mid-term follow up by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2021;23:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Rajpal S, Tong MS, Borchers J, Zareba KM, Obarski TP, Simonetti OP, Daniels CJ. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Findings in Competitive Athletes Recovering From COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:116-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Kramer CM, Carbone I, Sechtem U, Kindermann I, Gutberlet M, Cooper LT, Liu P, Friedrich MG. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Nonischemic Myocardial Inflammation: Expert Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3158-3176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 762] [Cited by in RCA: 1448] [Article Influence: 206.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Blagova O, Ainetdinova DH, Lutokhina YUA, Novosadov VM, Rud' RS, Zaitsev AYU, Kukleva AD, Alexandrova SA, Kogan EA. Post-COVID myocarditis diagnosed by endomyocardial biopsy and/or magnetic resonance imaging 2–9 months after acute COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:ehab724.1751. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Luetkens JA, Faron A, Isaak A, Dabir D, Kuetting D, Feisst A, Schmeel FC, Sprinkart AM, Thomas D. Comparison of Original and 2018 Lake Louise Criteria for Diagnosis of Acute Myocarditis: Results of a Validation Cohort. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2019;1:e190010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Sayegh MN, Goins AE, Hall MAK, Shin YM. Presentations, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Post-COVID Viral Myocarditis in the Inpatient Setting: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e39338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:811-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2516] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 478.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Fiorina L, Younsi S, Horvilleur J, Manenti V, Lacotte J, Raimondo C, Chemaly P, Salerno F, Ait Said M. [COVID-19 and arrhythmias]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2020;69:376-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, Pujol JC, Klaser K, Antonelli M, Canas LS, Molteni E, Modat M, Jorge Cardoso M, May A, Ganesh S, Davies R, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Astley CM, Joshi AD, Merino J, Tsereteli N, Fall T, Gomez MF, Duncan EL, Menni C, Williams FMK, Franks PW, Chan AT, Wolf J, Ourselin S, Spector T, Steves CJ. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 731] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 324.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Blitshteyn S, Whitelaw S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients. Immunol Res. 2021;69:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Goldstein DS. The possible association between COVID-19 and postural tachycardia syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:508-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Barizien N, Le Guen M, Russel S, Touche P, Huang F, Vallée A. Clinical characterization of dysautonomia in long COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:995-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1435] [Cited by in RCA: 1424] [Article Influence: 237.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Moody WE, Mahmoud-Elsayed HM, Senior J, Gul U, Khan-Kheil AM, Horne S, Banerjee A, Bradlow WM, Huggett R, Hothi SS, Shahid M, Steeds RP. Impact of Right Ventricular Dysfunction on Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19, According to Race. CJC Open. 2021;3:91-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Kim J, Volodarskiy A, Sultana R, Pollie MP, Yum B, Nambiar L, Tafreshi R, Mitlak HW, RoyChoudhury A, Horn EM, Hriljac I, Narula N, Kim S, Ndhlovu L, Goyal P, Safford MM, Shaw L, Devereux RB, Weinsaft JW. Prognostic Utility of Right Ventricular Remodeling Over Conventional Risk Stratification in Patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1965-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Li Y, Li H, Zhu S, Xie Y, Wang B, He L, Zhang D, Zhang Y, Yuan H, Wu C, Sun W, Zhang Y, Li M, Cui L, Cai Y, Wang J, Yang Y, Lv Q, Zhang L, Xie M. Prognostic Value of Right Ventricular Longitudinal Strain in Patients With COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2287-2299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ingul CB, Grimsmo J, Mecinaj A, Trebinjac D, Berger Nossen M, Andrup S, Grenne B, Dalen H, Einvik G, Stavem K, Follestad T, Josefsen T, Omland T, Jensen T. Cardiac Dysfunction and Arrhythmias 3 Months After Hospitalization for COVID-19. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Maestre-Muñiz MM, Arias Á, Mata-Vázquez E, Martín-Toledano M, López-Larramona G, Ruiz-Chicote AM, Nieto-Sandoval B, Lucendo AJ. Long-Term Outcomes of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 at One Year after Hospital Discharge. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |