Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111736

Revised: July 28, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 191 Days and 16.6 Hours

The electrocardiographic (ECG) presentation, with or without ST-segment eleva

To determine the prevalence, predictors, and impact of total occlusion of the infarct-related coronary artery on short-term mortality.

We conducted a prospective, single-center cohort study that included consecutive patients treated for AMI with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at the University Hospital Centre Sestre Milosrdnice in Zagreb, Croatia, between 2011 and 2018. Patients were divided into two groups based on the patency of the infarct-related artery: Those with an occluded coronary artery (OCA) and those with a patent coronary artery (PCA).

Among the 2483 patients (71.6% male) treated with PCI for AMI, 67.9% had an OCA, while 32.1% had a patent artery (PCA). Notably, 35.5% of NSTEMI patients had an OCA. Patients with OCA were younger, had fewer chronic comorbidities, and presented with more severe clinical symptoms. In contrast, patients with PCA were older and exhibited more extensive chronic atherosclerotic disease. Thirty-day mortality was significantly higher in the OCA group (7.29%) compared to the PCA group (3.52%, P < 0.001). OCA was identified as an independent predictor of mortality [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.0367, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.4543-6.3411]. Other independent predictors included age (HR = 1.0626; 95%CI: 1.0341-1.0919), Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events score (HR = 1.0065; 95%CI: 1.0011-1.0120), and ventricular tachycardia before or during PCI (HR = 3.8458; 95%CI: 1.4600-10.1299). ECG presentation (STEMI vs NSTEMI) was not an independent prognostic factor (HR = 1.0404; 95%CI: 0.5659-1.9128). Chronic statin therapy prior to AMI [odds ratios (OR) = 0.0168, 95%CI: 0.3674-0.9057], older age

Culprit-artery occlusion is a strong, independent determinant of short-term mortality. An occlusion-aware perspective refines risk stratification beyond ECG presentation and supports earlier invasive evaluation in NSTEMI patients with clinical/ECG signs of possible occlusion.

Core Tip: This large prospective study found that culprit coronary artery occlusion worsens the prognosis at 30 days, regardless of the electrocardiographic presentation. Patients with occluded arteries are younger and exhibited more severe clinical features, while those with patent arteries were older and had more chronic issues. The presence of occlusion increased the risk of short-term mortality threefold. Chronic statin use prior to the acute myocardial infarction was associated with a lower likelihood of artery occlusion. These findings suggest that angiographic assessment of culprit artery patency should be integrated into stratification of acute myocardial infarction beyond traditional ST-elevation/non-ST-segment patterns.

- Citation: Kos N, Zeljković I, Golubic K, Radeljic V, Erceg M, Delic-Brkljacic D, Cigrovski Berkovic M, Bulj N. Impact of total occlusion of the infarct-related coronary artery on mortality of 2483 patients with acute myocardial infarction. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 111736

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/111736.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111736

The electrocardiographic (ECG) remains one of the essential diagnostic tools for assessing patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The presence of ST-segment elevation indicates ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while its absence indicates non-STEMI (NSTEMI). This distinction is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment approach[1,2]. However, it’s important to note that up to 20% of patients with NSTEMI may have a completely occluded infarct-related artery (IRA), which is often linked to transmural ischemia. To date, most studies have classified patients based on their ECG presentation (STEMI vs NSTEMI) when assessing outcomes. However, there is ongoing debate about whether the patency of the IRA might be a stronger prognostic indicator than ECG findings alone. Emerging evidence suggests that NSTEMI patients with an occluded IRA may experience worse outcomes. This has led to a renewed examination of the ECG as the sole predictor of prognosis in cases of myocardial infarction[3]. Clinical and demographic factors that predispose to complete IRA occlusion vs preserved patency, regardless of ECG presentation, remain poorly defined. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prognostic impact of IRA patency (occluded vs patent IRA) in AMI patients on short-term (30-day) all-cause mortality and to identify clinical predictors of IRA occlusion.

We conducted a prospective, single-center cohort study based on a clinical registry that included consecutive patients treated for AMI with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at the University Hospital Centre Sestre milosrdnice, Zagreb, Croatia, between 2011 and 2018. All patients received treatment following the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines at the time. Revascularization was performed by five experienced interventional cardiologists, each with over five years of experience and performing more than 150 PCI procedures annually. The identification of the culprit coronary artery lesion was left to the discretion of the operator. In cases of multivessel coronary disease, operators determined the culprit lesion based on changes in the electrocardiogram, the location of ischemic changes observed on echocardiography, the angiographic significance of the stenosis, regression of chest pain, and/or changes in the electrocardiogram following the intervention. Given the period during which patients were enrolled in our study, the routine use of advanced hemodynamic and imaging assessment methods was not available, in accordance with national health insurance regulations. Patients were excluded if they were treated without PCI, diagnosed with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries, or underwent surgical revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting).

Data were collected from the hospital electronic medical records and patient charts. Mortality data were obtained from the Croatian National Institute of Public Health’s cause-of-death registry. Collected variables included baseline demographic data, medical history, chronic pre-admission pharmacotherapy, in-hospital course, complications, and procedural characteristics. All angiograms were blinded for outcomes and re-evaluated independently by two experienced interventional cardiologists. Chronic pharmacotherapy was considered relevant if the patient had been taking medication for at least four weeks before the index event. Significant carotid artery stenosis was defined as a luminal narrowing of more than 50%. Data that were incomplete or unavailable for the majority of patients - particularly those transferred from or to regional hospital centers - such as left ventricular ejection fraction, chronic therapy at discharge, and in-hospital mortality, were not included in the study.

Patients were divided into two groups based on the patency of IRA: Those with an occluded coronary artery (OCA) group and those with a patent coronary artery (PCA) group. A patent artery was defined as having visible antegrade flow of at least thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade I distal to the culprit lesion. Occlusion was defined as the complete absence of antegrade flow beyond the site of the lesion (TIMI 0), with no visible antegrade or retrograde collateral circulation. All patients were pretreated with 300 mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 600 mg of clopidogrel or 180 mg of ticagrelor, depending on current guidelines. All patients were followed until the primary endpoint was reached or for 30 days from the index hospitalization. The primary clinical endpoint was all-cause mortality during the follow-up period.

Statistical analysis was performed using appropriate methods depending on data distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges or as means with standard deviations, as appropriate. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. To assess statistical significance between groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables, and the χ2 test for discrete variables. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to multiple comparisons, adjustment by Benjamini-Hochberg was used. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated using Schoenfeld residuals.

Evaluation of survival over the 30-day follow-up period was performed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival rate between groups. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify independent predictors of 30-day mortality. To assess independent predictors of OCA, logistic regression analysis was employed. Multicollinearity among variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance statistics. A VIF > 5 and a tolerance < 0.2 were considered indicative of significant multicollinearity. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics, NY, United States).

A total of 2483 patients were included in the study, of whom 71.6% were male. The mean age of the cohort was 63.2 years. Among these patients, 1687 (67.94%) presented with an OCA, while 796 (32.05%) had a PCA. Notably, 18.4% of patients with an occluded artery presented with NSTEMI, whereas 23.1% of patients with a patent artery presented with STEMI. Out of the total number of patients with NSTEMI (949 patients), 337 patients (35.5%) presented with an OCA. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Statistically significant differences between the groups were observed. Patients in the PCA group were significantly older and had a higher burden of comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation (8.2% vs 5.7%), arterial hypertension (78.4% vs 71.1%), and diabetes mellitus (29.6% vs 20.9%). They also had more frequent manifestations of atherosclerosis at other vascular sites, including prior myocardial infarction (14.7% vs 10%), peripheral arterial disease (8.3% vs 5.4%), and carotid artery stenosis (6.8% vs 3.6%).

| Variable | Occluded artery (n = 1687, 67.9%) | Patent artery (n = 796, 32.1%) | P value |

| Age (years) | 63 (55-73) | 66.3 (58-75) | < 0.0001 |

| Male sex | 1206 (72.9) | 572 (71.87) | 0.584 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 95 (5.7) | 65 (8.2) | 0.018 |

| Arterial hypertension | 1176 (71.1) | 624 (78.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 346 (20.9) | 236 (29.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Family history of CV diseases | 545 (33.0) | 280 (35.2) | 0.649 |

| Smoking | 676 (40.6) | 278 (34.9) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 (25.3-30.9) | 27.8 (25.0-30.5) | 0.388 |

| Extent of atherosclerotic disease | |||

| Carotid stenosis | 60 (3.6) | 54 (6.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 89 (5.4) | 66 (8.3) | < 0.005 |

| Previous CABG | 26 (1.6) | 14 (1.8) | 0.735 |

| Previous PCI | 140 (8.5) | 89 (11.2) | 0.030 |

| Previous MI | 166 (10.0) | 117 (14.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous stroke | 83 (5.0) | 46 (5.8) | 0.427 |

| Chronic therapy (> 4 weeks before AMI) | |||

| ASA | 269 (16.3) | 178 (22.4) | < 0.0001 |

| ACEi/ARB | 618 (37.4) | 335 (22.1) | 0.005 |

| Beta-blockers | 372 (22.5) | 225 (28.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Statins | 255 (15.4) | 174 (21.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Variable | Occluded artery (n = 1687, 67.9%) | Patent artery (n = 796, 32.1%) | P value |

| STEMI | 1350 (81.6) | 184 (23.1) | < 0.0001 |

| VT before/during PCI | 48 (2.9) | 17 (2.1) | 0.278 |

| Systolic BP on admission (mmHg) | 130 (115-150) | 140 (120-155) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 107 (6.5) | 19 (2.49) | < 0.0001 |

| Out-of-hospital arrest | 62 (3.7) | 12 (1.5) | 0.003 |

| GRACE score | 141.5 (96-175) | 144 (75-106) | 0.300 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 143 (131-153) | 141 (129-150) | 0.003 |

| eGFR (mL/minutes/1.73 m2) | 73 (59-88) | 73 (58-87) | 0.539 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.5 (2.7-4.2) | 3.1 (2.3-3.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Creatine kinase - peak (U/L) | 1629 (716-3406) | 354 (163-812) | < 0.0001 |

| Troponin I - peak (ng/L) | 20315 (16289-22154) | 55000 (1461-3525) | < 0.0001 |

| PCI-related findings | |||

| SYNTAX score | 21 (17-26) | 23 (18-27) | < 0.0001 |

| TIMI 3 as the final angiogram | 1284 (77.6) | 685 (86.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Stenosis of the LMCA | 60 (3.6) | 80 (29.3) | < 0.0001 |

These patients also demonstrated more extensive coronary atherosclerosis, as reflected by a higher SYNergy between PCI with TAXus and Cardiac Surgery score [median 23 (interquartile range: 18-27) vs 21 (interquartile range: 17-26)], higher prevalence of left main coronary artery stenosis (29.3% vs 3.6%), and more frequent chronic use of medications known to improve outcomes in atherosclerotic disease, such as acetylsalicylic acid (22.4% vs 16.3%) and statins (21.9% vs 15.4%). Conversely, patients with OCA more frequently presented with severe clinical findings: Lower systolic blood pressure on admission [130 (115-150) mmHg vs 140 (120-155) mmHg], higher incidence of cardiogenic shock (6.5% vs 2.5%), and more frequent out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (3.7% vs 1.5%). They also had significantly higher peak levels of cardiac biomarkers, including troponin I [20315 (16289-22154) ng/L vs 5500 (1461-3525) ng/L] and creatine kinase [1629 (716-3406) U/L vs 354 (163-812) U/L], and achieved TIMI 3 flow less frequently at the end of the procedure (77.6% vs 86.1%).

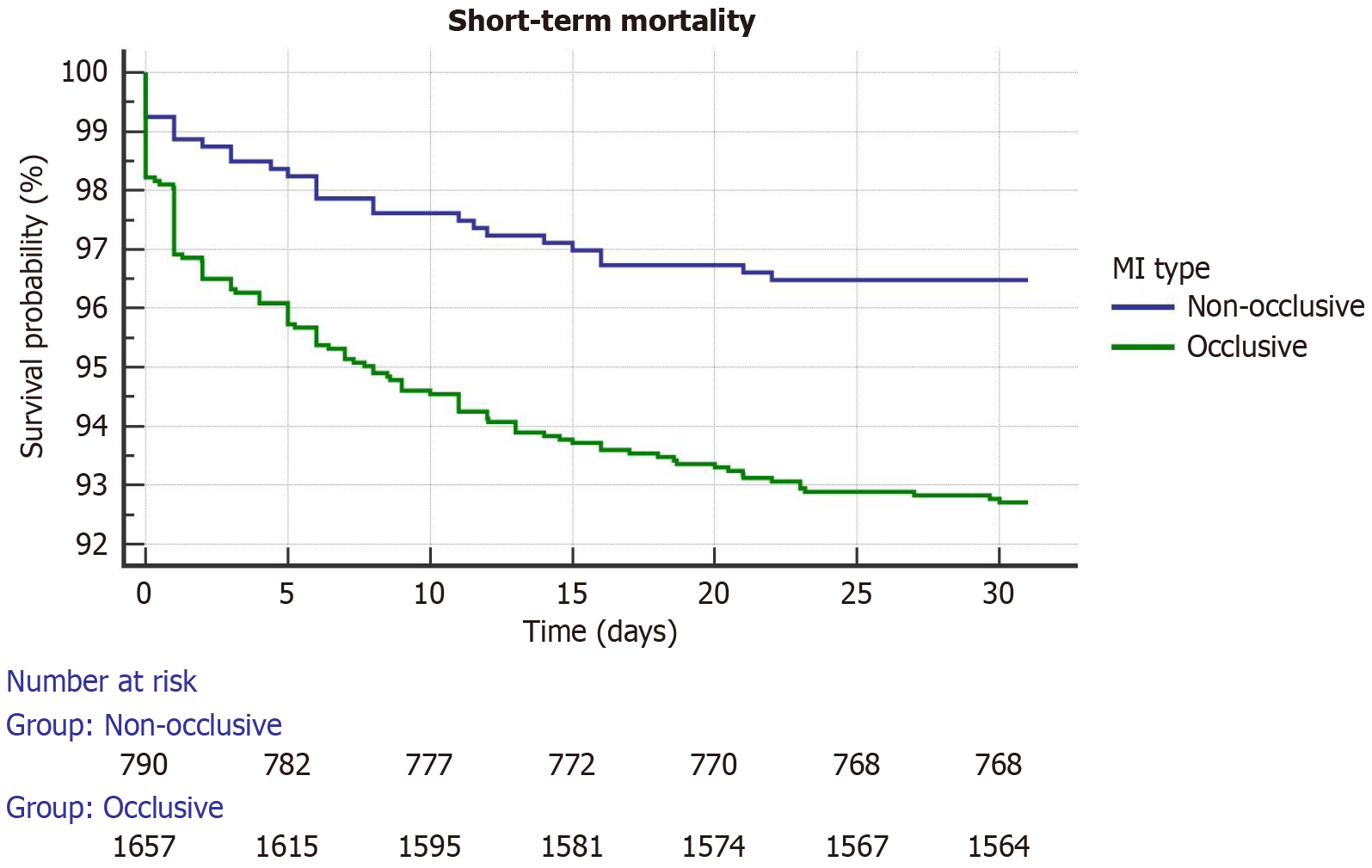

Within 30 days, all-cause mortality occurred in 123 patients (7.29%) in the OCA group and in 28 patients (3.52%) in the PCA group (P < 0.001). No significant interoperator mortality difference was observed. Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 1) and log-rank test demonstrated a significantly lower probability of survival in patients who presented with an OCA during the follow-up period (χ2 = 13.4527; df = 1; P < 0.0002).

Independent predictors of OCA (Table 3) included age [odds ratios (OR) = 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.950-0.989], peak troponin I value (OR = 1.000, 95%CI: 1.0000-1.0001), and prior statin therapy (OR = 0.5867, 95%CI: 0.3622-0.9503). Independent predictors of 30-day all-cause mortality (Table 4) were: Age [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.0626, 95%CI: 1.0341-1.0919], myocardial infarction with an OCA (HR = 3.0367, 95%CI: 1.4543-6.3411), Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score (HR = 1.0065, 95%CI: 1.0011–1.0120), and presence of ventricular tachycardia before or during PCI (HR = 3.7458, 95%CI: 1.4600-10.1299). All variables included in the multivariable model had VIF values < 2 and tolerance > 0.5, indicating no significant multicollinearity.

| Covariate | P value | Odd ratio | 95%CI |

| Age | 0.0023 | 0.9722 | 0.9547-0.9900 |

| Sex (female) | 0.2756 | 1.3301 | 0.7965-2.2212 |

| Troponin I (max value) | < 0.0001 | 1.0000 | 1.0000-1.0001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0.8778 | 0.9400 | 0.4271-2.0688 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.1362 | 0.6968 | 0.4333-1.1206 |

| Body mass index | 0.3799 | 1.0212 | 0.9744-1.0703 |

| eGFR | 0.0794 | 0.9918 | 0.9827-1.0010 |

| Statin therapy before AMI | 0.0168 | 0.5768 | 0.3674-0.9057 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.3112 | 0.7415 | 0.6784-1.2154 |

| Covariate | P value | Hazard ratio | 95%CI |

| Age | < 0.0001 | 1.0626 | 1.0341-1.0919 |

| Sex (female) | 0.0974 | 1.5527 | 0.9229-2.6123 |

| ECG presentation (NSTEMI) | 0.8986 | 1.0404 | 0.5659-1.9128 |

| Occluded culprit coronary artery | 0.0031 | 3.0367 | 1.4543-6.3411 |

| Ventricular tachycardia before or during PCI | 0.0064 | 3.8458 | 1.4600-10.1299 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0.1227 | 1.8168 | 0.8513-3.8774 |

| Statin therapy before myocardial infarction | 0.3300 | 1.3523 | 0.7368-2.4820 |

| BMI | 0.2116 | 1.0357 | 0.9802-1.0943 |

| GRACE | 0.0188 | 1.0065 | 1.0011-1.0120 |

| LDL - cholesterol | 0.2744 | 0.8894 | 0.7208-1.0974 |

| SYNTAX | 0.8050 | 1.0050 | 0.9659-1.0458 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.2122 | 1.2121 | 0.5257-1.3124 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.9878 | 1.4245 | 0.7854-1.3154 |

Patients who presented with OCA had a lower probability of 30-day survival (short-term outcome). After adjustment for other factors, coronary artery occlusion emerged as an independent predictor of short-term survival, regardless of ECG presentation (which was not a statistically significant predictor). Factors associated with a lower probability of developing an OCA included older age, lower troponin levels, and chronic statin therapy for at least 4 weeks prior to the AMI. When examining mortality in patients with myocardial infarction, the dominant comparison groups have traditionally been STEMI and NSTEMI (with reported 30-day mortality rates of approximately 5%-7% for STEMI and about 3% for NSTEMI), while occlusion as a predictor of mortality has almost exclusively been assessed within the NSTEMI patient group, mostly investigating 1-year mortality. Our findings demonstrate that patients with OCA had worse 30-day survival, as evidenced by mortality rates at the end of the follow-up period and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. After adjusting for other clinical risk factors, coronary artery occlusion remained an independent predictor of mortality (HR = 3.04; 95%CI: 1.45-6.34; P = 0.0031). Results from registries with similar characteristics and patient populations to our study showed that one-month mortality in occlusive NSTEMI was approximately 5.5%, compared to 3.5% in non-occlusive NSTEMI (P = 0.017)[4]. By including all AIM patients in the analysis, our study found that this difference further increased, with a one-month mortality of 7.3% for occlusive infarctions and 3.5% for non-occlusive infarctions. Available data show that angiographic type on AMI (OCA vs PCA) is relevant in short-term follow-up, while some reports suggest that such a difference diminishes over long (1 year) and very long-term (> 5 years) follow-up[4,5]. Patients with occlusive NSTEMI had a significantly worse one-year prognosis compared to both STEMI and nonocclusive NSTEMI[3]. Previous studies have shown that the time to revascularization did not differ significantly between occlusive and non-occlusive NSTEMI (> 10 hours in both groups), yet it remained considerably longer than in patients with STEMI (< 2 hours). Currently, there are no available data to determine whether an accurate angiographic diagnosis of occlusive infarction, followed by prompt revascularization - known to improve clinical outcomes - would significantly impact prognosis because it would be difficult to evaluate considering current clinical guidelines. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to assume that the observed difference in mortality between occlusive and non-occlusive infarctions can be attenuated through more precise diagnosis and timely revascularization of all occlusive infarctions[4,6].

Our study demonstrated that reperfusion success, as measured by post-procedural TIMI 3 flow, was lower in patients with coronary artery occlusion. It is well known that patients with coronary artery occlusion have a lower likelihood of achieving post-procedural TIMI 3 flow. This finding is highly dependent on the timing of revascularization, as shown by several studies demonstrating that patients with coronary artery occlusion but without ST-segment elevation on ECG underwent delayed revascularization and exhibited a lower incidence of TIMI III flow compared to occluded patients who were revascularized immediately. Abusharekh et al[7] reported that the incidence of the no-reflow phenomenon is similar across all OCA, regardless of ECG presentation, and is significantly higher than in PCA[3,7,8]. These observations further emphasize that timely intervention and revascularization in patients with OCA are crucial for achieving adequate flow restoration.

In our study, ECG presentation (STEMI vs NSTEMI) was not an independent predictor of mortality (P = 0.8986), and the results showed that patients with coronary occlusion were at significantly higher risk of adverse outcomes regardless of ECG findings. Although electrocardiography remains the cornerstone of diagnosis and prognosis, there is growing evidence suggesting that it is not an independent predictor of outcomes. In addition to the well-known pitfalls in the interpretation of “ischemic” ECGs - such as distal LCx occlusion, occlusion of aortocoronary bypass grafts, or significant left main coronary artery stenosis - smaller myocardial infarction areas that impact clinical outcomes are also frequently overlooked on ECG, as confirmed by perfusion studies. In the Welch’s study, it was shown that patients presenting with a “normal” ECG experienced in-hospital complications in 19% of cases, compared with 27.5% for those with non-specific ECG changes and 34% for those with ischemic ECG patterns, indicating that the absolute risk remains clinically significant[9,10]. Patients with occluded IRA presented more frequently with more severe clinical features - cardiogenic shock, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, significantly lower systolic blood pressure, and higher high-sensitivity troponin levels. These findings reinforce the need for urgent revascularization, especially given the well-established benefit of early revascularization in hemodynamically unstable patients[11-15].

Higher levels of cardiac biomarkers in the OCA group likely reflect larger infarct size and may represent a potential confounder in the association with short-term mortality. However, the strong prognostic impact of total occlusion remained significant even after adjustment for peak biomarker levels. This suggests that total occlusion may carry prognostic value beyond infarct size alone. In contrast, patients with PCA had a significantly higher burden of chronic comorbidities, and consequently, a higher cardiovascular risk - atrial fibrillation, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, carotid artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, previous PCI, and prior myocardial infarction. These patients were significantly older and more frequently received outcomes-modulating medications. These findings are similar to other registry-based studies and in accordance with the classic atherosclerotic concept - occlusion is thought to result from thrombus superimposition on a ruptured, angiographically non-significant atherosclerotic plaque with a thin fibrous cap and a non-calcified necrotic core. This phenotype is more frequently observed in younger patients, smokers, and those with fewer comorbidities. In contrast, PCAs are more commonly found in older patients with multiple comorbidities - particularly diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease - and are associated with widespread atherosclerotic disease, thicker fibrous caps, and heavily calcified cores[4,16-18]. Perhaps direct infarct-size imaging (e.g., cardiac magnetic resonance imaging) and sizing could be a better outcome marker than troponin levels.

Post-NSTEMI chronic coronary syndrome patients have been shown to have a less favorable risk profile, poorer self-reported health, and worse long-term outcomes than post-STEMI patients, who have worse short-term outcomes[6,19-23]. In a meta-analysis, among NSTEMI patients, the incidence of acute complications (particularly cardiogenic shock) and mortality is higher when they present with an occluded coronary artery[24,25]. Our study demonstrated that the mentioned observation can be applied to all patients with OCA, independent of ECG presentation. The GRACE score, a well-known indicator of the acute severity of patients with myocardial infarction, according to our model, was an independent predictor of short-term outcomes. An increase in GRACE score by 10 points was associated with a 6.5% increase in the mortality risk. In our study, as well as in some similar studies, the GRACE score did not differ based on the patency of the coronary artery. Our study supports the usefulness of the GRACE score for short-term outcome stratification, but it does not appear to be helpful as a diagnostic tool for distinguishing between OCA and PCA[4,26-30].

Ventricular tachycardia before or during PCI occurred with equal frequency across both angiographic subgroups and was independently associated with worse short-term outcomes. Ventricular tachycardia was linked to a nearly fourfold increased risk of death (HR = 3.8458; P = 0.0064), underscoring its known role as a marker of extensive ischemia or prior myocardial injury and its association with a higher risk of sudden cardiac death[31,32]. Age proved to be a strong and expected predictor of mortality, with each additional year of life increasing the risk of death by more than 6%. This is consistent with previous studies showing that older patients have a higher prevalence of comorbidities, reduced response to reperfusion therapy, and increased vulnerability to hemodynamic instability after infarction. Despite being a higher-risk group, elderly patients are less likely to receive evidence-based therapies and tend to have worse outcomes[29,33,34].

Our study found that chronic statin therapy for at least 4 weeks prior to AMI was associated with a lower likelihood of developing OCA (OR = 0.5768; 95%CI: 0.3674-0.9057; P = 0.0168). To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to link pre-event statin use with the angiographic type of AMI. Available studies showed that previous chronic statin therapy increases the proportion of patients presenting with angina pectoris/NSTEMI rather than STEMI[35-37]. The mechanisms likely involve pleiotropic effects - plaque stabilization, reduced systemic and local inflammation, improved endothelial function, and reduced hypercoagulability[38,39]. van Rosendael et al[40] demonstrated that statin therapy enhances the stability of the atherosclerotic cap by increasing the calcium content within the plaque. Moreover, it is well established that statins inhibit macrophage proliferation, leading to reduced production of matrix metalloproteinases, and exert anti-inflammatory effects by attenuating the activity of inflammatory cells, thereby decreasing the thrombogenicity of the plaque[40-42]. All of the aforementioned mechanisms may consequently lead to reduced formation of extensive thrombus and a higher likelihood of preventing complete coronary artery occlusion.

Patients who had previously been treated with statins more frequently had prior clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis at other sites (peripheral artery disease, carotid artery disease) and lower initial low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Previous studies have shown that polyvascular patients tend to have a more diffuse form of atherosclerotic coronary disease, which explains the statistically significantly higher SYNergy between PCI with TAXus and Cardiac Surgery score observed in patients who had been previously treated with statins[43]. Available data show that prior statin therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels at admission were not associated with short-term mortality, possibly due to the regular postprocedural administration of potent statins, which may offset the pre-existing benefits of chronic therapy, a finding also noticed in our study[38,44]. Although our PCA group had a higher proportion of patients with final TIMI 3 flow, it is plausible that higher statin usage contributed to this outcome, warranting further investigation[45].

This study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. There are a few factors that limit the generalizability of our results to all AMI patients: Firstly, a single-center study design and observational character of the study, exclusion of patients with AMI treated without PCI, and treatment algorithm changes during the study period. Additionally, data on left ventricular ejection fraction were missing for a significant proportion of patients who were transferred from regional hospitals within the primary PCI network, so these findings were not analyzed. Finally, data regarding patient adherence to the prescribed therapy were not available.

Our findings support growing evidence that the underlying pathophysiology of myocardial infarction plays a significant role in prognosis. Treatment decisions should consider multiple factors, with ECG findings being only one among them. These results emphasize the need for a revised risk stratification approach. Patients presenting with an AMI without clear ST-segment elevation should undergo a thorough evaluation during the initial assessment to identify potential indicators of coronary artery occlusion. These may include younger age, lower overall cardiovascular risk, more severe initial clinical presentation, ongoing chest pain, and detailed ECG analysis, including additional leads. This study also contri

| 1. | Moholdt T, Ashby ER, Tømmerdal KH, Lemoine MCC, Holm RL, Sætrom P, Iversen AC, Ravi A, Simpson MR, Giskeødegård GF. Randomised controlled trial of exercise training during lactation on breast milk composition in breastfeeding people with overweight/obesity: a study protocol for the MILKSHAKE trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2023;9:e001751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Clay AS, Hainline BE. Hyperammonemia in the ICU. Chest. 2007;132:1368-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Herman R, Smith SW, Meyers HP, Bertolone DT, Leone A, Bermpeis K, Viscusi M, Martonak M, Bahyl J, Demolder A, Perl L, Wojakowski W, Bartunek J, Barbato E. Poor prognosis of total culprit artery occlusion in patients presenting with NSTEMI. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:ehad655.1536. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Karwowski J, Poloński L, Gierlotka M, Ciszewski A, Hawranek M, Bęćkowski M, Gąsior M, Kowalik I, Szwed H. Total coronary occlusion of infarct-related arteries in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary revascularisation. Kardiol Pol. 2017;75:108-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kos N, Zeljković I, Krčmar T, Golubić K, Šaler F, Erceg M, Delić-Brkljačić D, Bulj N. Acute Occlusion of the Infarct-Related Artery as a Predictor of Very Long-Term Mortality in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Cardiol Res Pract. 2021;2021:6647626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Krishnamurthy SN, Pocock S, Kaul P, Owen R, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Nicolau JC, Simon T, Westermann D, Yasuda S, Andersson K, Brandrup-Wognsen G, Hunt PR, Brieger DB, Cohen MG. Comparing the long-term outcomes in chronic coronary syndrome patients with prior ST-segment and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the TIGRIS registry. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e070237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abusharekh M, Kampf J, Dykun I, Souri K, Backmann V, Al-Rashid F, Jánosi RA, Totzeck M, Lawo T, Rassaf T, Mahabadi AA. Acute coronary occlusion with vs. without ST elevation: impact on procedural outcomes and long-term all-cause mortality. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2024;10:402-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Terlecki M, Wojciechowska W, Dudek D, Siudak Z, Plens K, Guzik TJ, Drożdż T, Pęksa J, Bartuś S, Wojakowski W, Grygier M, Rajzer M. Impact of acute total occlusion of the culprit artery on outcome in NSTEMI based on the results of a large national registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lloyd-Jones DM, Camargo CA Jr, Lapuerta P, Giugliano RP, O'Donnell CJ. Electrocardiographic and clinical predictors of acute myocardial infarction in patients with unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1182-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Welch RD, Zalenski RJ, Frederick PD, Malmgren JA, Compton S, Grzybowski M, Thomas S, Kowalenko T, Every NR; National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 and 3 Investigators. Prognostic value of a normal or nonspecific initial electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2001;286:1977-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, Fuernau G, de Waha S, Meyer-Saraei R, Nordbeck P, Geisler T, Landmesser U, Skurk C, Fach A, Lapp H, Piek JJ, Noc M, Goslar T, Felix SB, Maier LS, Stepinska J, Oldroyd K, Serpytis P, Montalescot G, Barthelemy O, Huber K, Windecker S, Savonitto S, Torremante P, Vrints C, Schneider S, Desch S, Zeymer U; CULPRIT-SHOCK Investigators. PCI Strategies in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2419-2432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 876] [Article Influence: 97.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Freund A, Desch S, Thiele H. Revascularization in cardiogenic shock. Herz. 2020;45:537-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Henry TD, Tomey MI, Tamis-Holland JE, Thiele H, Rao SV, Menon V, Klein DG, Naka Y, Piña IL, Kapur NK, Dangas GD; American Heart Association Interventional Cardiovascular Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Invasive Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e815-e829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Dzavik V, Buller CE, Aylward P, Col J, White HD; SHOCK Investigators. Early revascularization and long-term survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;295:2511-2515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baigent C, Collins R, Appleby P, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1998;316:1337-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dong L, Mintz GS, Witzenbichler B, Metzger DC, Rinaldi MJ, Duffy PL, Weisz G, Stuckey TD, Brodie BR, Yun KH, Xu K, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW, Maehara A. Comparison of plaque characteristics in narrowings with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI/unstable angina pectoris and stable coronary artery disease (from the ADAPT-DES IVUS Substudy). Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mori H, Torii S, Kutyna M, Sakamoto A, Finn AV, Virmani R. Coronary Artery Calcification and its Progression: What Does it Really Mean? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:127-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jin HY, Weir-McCall JR, Leipsic JA, Son JW, Sellers SL, Shao M, Blanke P, Ahmadi A, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ, Conte E, Andreini D, Pontone G, Budoff MJ, Gottlieb I, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Cademartiri F, Maffei E, Marques H, de Araujo Goncalves P, Shin S, Choi JH, Virmani R, Samady H, Stone PH, Berman DS, Narula J, Shaw LJ, Bax JJ, Chinnaiyan K, Raff G, Al-Mallah MH, Lin FY, Min JK, Sung JM, Lee SE, Chang HJ. The Relationship Between Coronary Calcification and the Natural History of Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14:233-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abbott JD, Ahmed HN, Vlachos HA, Selzer F, Williams DO. Comparison of outcome in patients with ST-elevation versus non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:190-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Polonski L, Gasior M, Gierlotka M, Osadnik T, Kalarus Z, Trusz-Gluza M, Zembala M, Wilczek K, Lekston A, Zdrojewski T, Tendera M; PL-ACS Registry Pilot Group. A comparison of ST elevation versus non-ST elevation myocardial infarction outcomes in a large registry database: are non-ST myocardial infarctions associated with worse long-term prognoses? Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:70-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Goldberg RJ, Currie K, White K, Brieger D, Steg PG, Goodman SG, Dabbous O, Fox KA, Gore JM. Six-month outcomes in a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome (the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:288-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Roston TM, Aghanya V, Savu A, Fordyce CB, Lawler PR, Jentzer J, Wong GC, Brunham LR, Senaratne J, van Diepen S, Kaul P. Premature Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With Invasive Revascularization: Comparing STEMI With NSTEMI in a Population-Based Study of Young Patients. Can J Cardiol. 2024;40:2079-2088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takeji Y, Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Yamamoto K, Matsumura-Nakano Y, Nagao K, Taniguchi R, Yamaji K, Tada T, Kato ET, Yoshikawa Y, Obayashi Y, Suwa S, Inoko M, Ehara N, Tamura T, Onodera T, Watanabe H, Toyofuku M, Nakatsuma K, Sakamoto H, Ando K, Furukawa Y, Sato Y, Nakagawa Y, Kadota K, Kimura T; CREDO-Kyoto AMI Registry Wave-2 Investigators. Differences in mortality and causes of death between STEMI and NSTEMI in the early and late phases after acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lange SA, Engelbertz CM, Feld J, Makowski L, Karanatsios G, Fischer AJ, Guenster C, Droege P, Ruhnke T, Gerss J, Reinecke H, Koeppe J. Differences in treatment and outcome of patients with ST- Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) and Non-STEMI in Germany. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:ehae666.3573. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Hung CS, Chen YH, Huang CC, Lin MS, Yeh CF, Li HY, Kao HL. Prevalence and outcome of patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with occluded "culprit" artery - a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2018;22:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bahrmann P, Rach J, Desch S, Schuler GC, Thiele H. Incidence and distribution of occluded culprit arteries and impact of coronary collaterals on outcome in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and early invasive treatment strategy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:457-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kumar D, Ashok A, Saghir T, Khan N, Solangi BA, Ahmed T, Karim M, Abid K, Bai R, Kumari R, Kumar H. Prognostic value of GRACE score for in-hospital and 6 months outcomes after non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Egypt Heart J. 2021;73:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang XF, Zhao M, Liu F, Sun GR. Value of GRACE and SYNTAX scores for predicting the prognosis of patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:10143-10150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yin G, Abdu FA, Liu L, Xu S, Xu B, Luo Y, Lv X, Fan R, Che W. Prognostic Value of GRACE Risk Scores in Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Non-obstructive Coronary Arteries. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:582246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Guo T, Xi Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Zheng J, Dou K, Xu B, Qiao S, Yang W, Gao R. Prognostic value of GRACE and CHA2DS2-VASc score among patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Ann Med. 2021;53:2215-2224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mont L, Cinca J, Blanch P, Blanco J, Figueras J, Brotons C, Soler-Soler J. Predisposing factors and prognostic value of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1670-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hanada K, Kinjo T, Yokoyama H, Tsushima M, Senoo M, Ichikawa H, Nishizaki F, Shibutani S, Yokota T, Okumura K, Tomita H. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcome Associated With Ventricular Tachycardia or Fibrillation in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ J. 2024;88:1254-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Acharya D. Predictors of Outcomes in Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. Cardiol Rev. 2018;26:255-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ahmed E, Alhabib KF, El-Menyar A, Asaad N, Sulaiman K, Hersi A, Almahmeed W, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Amin H, Al-Motarreb A, Al Saif S, Singh R, Al-Lawati J, Al Suwaidi J. Age and clinical outcomes in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Weidmann L, Obeid S, Mach F, Shahin M, Yousif N, Denegri A, Muller O, Räber L, Matter CM, Lüscher TF. Pre-existing treatment with aspirin or statins influences clinical presentation, infarct size and inflammation in patients with de novo acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2019;275:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ndrepepa G, Fusaro M, King L, Cassese S, Tada T, Schömig A, Kastrati A. Statin pretreatment and presentation patterns in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiol J. 2013;20:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Trivi M, Henquin R, Costabel J, Conde D. Statin pretreatment and presentation patterns in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Xiangya Med. 2017;2:65. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Fuernau G, Eitel I, Wöhrle J, Kerber S, Lauer B, Pauschinger M, Schwab J, Birkemeyer R, Pfeiffer S, Mende M, Brosteanu O, Neuhaus P, Desch S, de Waha S, Gutberlet M, Schuler G, Thiele H. Impact of long-term statin pretreatment on myocardial damage in ST elevation myocardial infarction (from the AIDA STEMI CMR Substudy). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Oesterle A, Liao JK. The Pleiotropic Effects of Statins - From Coronary Artery Disease and Stroke to Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2019;17:222-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | van Rosendael AR, van den Hoogen IJ, Gianni U, Ma X, Tantawy SW, Bax AM, Lu Y, Andreini D, Al-Mallah MH, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Chinnaiyan K, Choi JH, Conte E, Marques H, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Gottlieb I, Hadamitzky M, Leipsic JA, Maffei E, Pontone G, Shin S, Kim YJ, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Sung JM, Lee SE, Virmani R, Samady H, Sato Y, Stone PH, Berman DS, Narula J, Blankstein R, Min JK, Lin FY, Shaw LJ, Bax JJ, Chang HJ. Association of Statin Treatment With Progression of Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque Composition. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Luan Z, Chase AJ, Newby AC. Statins inhibit secretion of metalloproteinases-1, -2, -3, and -9 from vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:769-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Chamani S, Kooshkaki O, Moossavi M, Rastegar M, Soflaei SS, McCloskey AP, Banach M, Sahebkar A. The effects of statins on the function and differentiation of blood cells. Arch Med Sci. 2023;19:1314-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bay B, Sharma R, Roumeliotis A, Power D, Sartori S, Murphy J, Vogel B, Smith KF, Oliva A, Hooda A, Sweeny J, Dangas G, Kini A, Krishnan P, Sharma SK, Mehran R. Impact of Polyvascular Disease in Patients Undergoing Unprotected Left Main Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2024;222:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lanza O, Cosentino N, Lucci C, Resta M, Rubino M, Milazzo V, De Metrio M, Trombara F, Campodonico J, Werba JP, Bonomi A, Marenzi G. Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Clin Med. 2022;11:5298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | de Carvalho Cantarelli MJ, Gioppato S, Castello HJ, Gonçalves R, Ribeiro EKP, de Freitas Guimarães JB, Navarro EC, Maksud D, Vardi JCF. Impact of prior statin use on percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in acute coronary syndrome. Revista Brasileira de Cardiologia Invasiva (English Edition). 2015;23:108-113. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/