Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111254

Revised: July 25, 2025

Accepted: December 4, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 203 Days and 14.8 Hours

Blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI) is a life-threatening injury, commonly asso

To review higher-grade injuries. NOM can be favored for selected patients with grade III injuries.

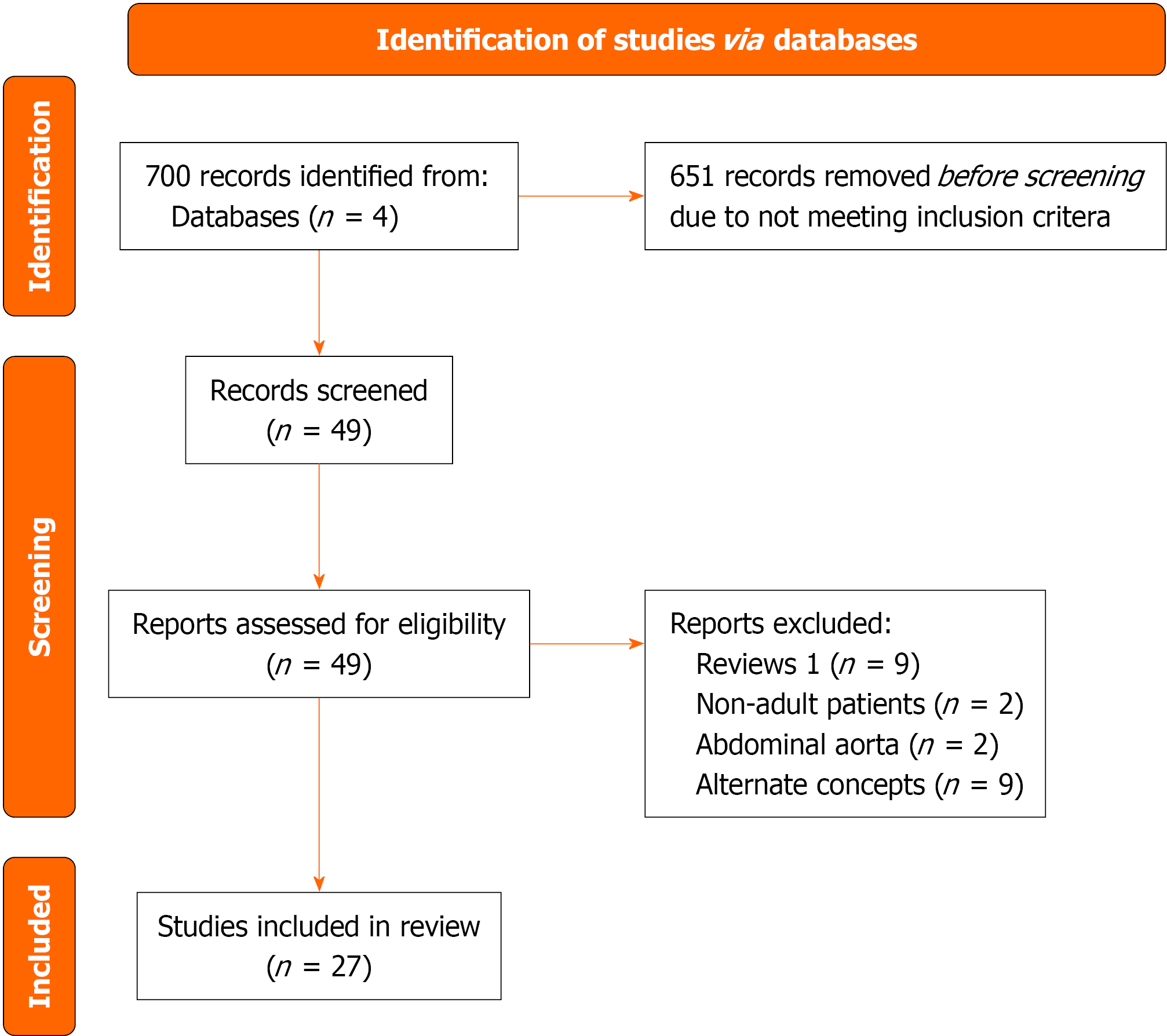

A retrospective review of literature to assess NOM in BTAI, using the PubMed, CINHAL, EBSCO, and Google Scholar databases, included articles published in the last 20 years between January 2003 and December 2023. Studies included Cohort studies, case-control studies, and observational studies. Two authors in

We identified 27 studies in our review that met the selection criteria. Most of the studies were based on retrospective analysis of institutional data, and only 16 papers reported BTAI in accordance with SVS reporting standards. A trend of increasing mortality across the BTAI grade was observed. There were heterogeneous results regarding outcomes after non-operative compared with endovascular and surgical repair. For grade I and II BTAI, NOM was associated with lower mortality, reduced rates of unplanned intervention, and resolution of pathology on follow-up. There were reports of NOM of grade III BTAI with reasonable outcomes and a high rate of resolution on follow-up, but data were limited due to very few studies focusing on this subgroup.

This review article provides the most up-to-date literature. Currently literature supporting the NOM for low-grade BTAI (grades I and II) treatment. Current SVS guidelines recommend endovascular repair for grade III BTAI patients; however, a few studies showed that grade III BTAI can be managed non-operatively with active surveillance in a selected group of patients. Literature requires further studies to compare NOM vs TEVAR in higher-grade BTAI population.

Core Tip: The non-operative management of blunt traumatic grade I aortic injury is a relatively common practice. The management of grade II aortic injury varies; some providers prefer an endovascular approach, while others prefer non-operative management. Successful non-operative management is associated with lower mortality and resolution of the primary pathology. However, non-operative management if not routinely applied for higher grade aortic injuries and the majority prefer an endovascular approach for higher grade, III or more, injury.

- Citation: Embel V, Hafeez MS, Russo L, Ahmed N. Non-operative management of blunt traumatic aortic injuries. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 111254

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/111254.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111254

Blunt traumatic aortic injury (BTAI) is a life-threatening condition caused by rapid deceleration forces, commonly associated with high-speed motor vehicle collisions, falls from significant heights, and other blunt trauma mechanisms. Despite improvement in diagnosis and treatment, thoracic aortic injuries remain highly fatal[1-3]. Aortic injuries can occur anywhere from the ascending aorta to the iliac bifurcation. The aortic isthmus is the most frequently affected site due to its anatomical fixation between the mobile aortic arch and the descending thoracic aorta[4]. The spectrum of BTAI ranges from minor intimal tears to complete aortic rupture, with the latter often being fatal before hospital arrival[2]. Historically, open surgical repair was the standard treatment for BTAI, but it was associated with significant morbidity and perioperative mortality[1,3,5,6]. With the advancement of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), management strategies have shifted to minimally invasive treatment, demonstrating improved survival rates and reduced complications compared to open repair. More recently, non-operative management (NOM) has emerged as an alternative stra

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) classifies BTAI into four grades: Grade I (intimal tear), grade II (intramural hematoma), grade III (pseudoaneurysm), and grade IV (rupture)[8-10]. While TEVAR is generally recommended for grades II-IV, emerging evidence suggests that some grade II and even select grade III injuries may be managed conservatively with strict blood pressure control and serial imaging[4,7]. Recent studies have demonstrated promising outcomes for NOM in higher-grade injuries when carefully selected, challenging the traditional approach of immediate TEVAR[3,11,12]. This review evaluates the NOM of higher-grade BTAI, examining patient selection criteria, clinical outcomes, and long-term safety. By synthesizing current evidence, we seek to clarify the role of NOM in the high-grade BTAI patient population and provide insight into best practices for its implementation.

We performed a review of the literature to assess the current evidence regarding NOM of BTAI. We included studies that met the following eligibility criteria: (1) Study design: Cohort studies, case-control studies, randomized-controlled trials and observational studies; (2) Population: Adult patients (≥ 18 years old) diagnosed with BTAI; (3) Intervention: NOM (consisting of observation, medical management andserial imaging), open surgical repair and endovascular techniques; and (4) Outcomes: Primary outcomes - mortality rates, aortic rupture, and need for surgical intervention; secondary outcomes - complications (e.g., infection, end-organ failure), long-term morbidity, and survival rates.

Studies published in English.

We excluded studies that focused on traumatic injuries not involving the aorta, studies with pediatric populations, and those without clear outcome reporting.

Information sources: We conducted a comprehensive search for relevant studies using the following electronic databases: PubMed, CINHAL, EBSCO, and Google Scholar. We also reviewed the references of included studies to identify addi

Study selection: Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies for potential eligibility. Full-text articles of selected studies were obtained and assessed for inclusion.

Data extraction: Data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a pre-defined data extraction form. The following information was collected from each included study: (1) Study design and year of publication; (2) Patient demographics (e.g., age, sex); (3) Details of the BTAI (e.g., injury grade); and (4) Primary and secondary outcomes (mortality, complications, need for surgery, long-term outcomes). We tabulated data on short-term mortality, aortic-related mortality (ARM), and the rate of intervention following initial NOM. Where available, we also noted progression or resolution of aortic pathology on imaging follow-up.

We assessed the strength of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation system considers factors such as study limitations, consistency of results, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and the risk of publication bias. This process was used to evaluate the overall quality of evidence for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Our search identified approximately 700 studies, of which 49 were selected for review of the article, and 27 were chosen for inclusion (Figure 1). Data from these studies were included in Table 1. Twenty-five studies were retrospective in nature, with only two studies that were prospective. Twenty studies collected data from a single institute, while three collected patient data from multiple institutions. Four studies utilized large databases such as the National Trauma Data Bank, the Aortic Trauma Foundation, and the Vascular Quality Initiative. The majority of the studies were based in the United States (17 of 27, 62.9%), Canada (2 of 27, 7.4%)[5,6], and Spain (2 of 27, 7.4%)[13,14] along with single studies from Austria[15], China[16], Japan[17], Qatar[18], South Korea[11] and one international study[19]. There was significant variation in the number of patients reported in each study. The studies with the seven largest sample sizes were either based on registry data or from multiple participating hospitals[3,12,19-23]. The only study by McCurdy et al[24] from Indiana University included more than 200 patients. All studies except two reported both NOM as well as intervention; Ott et al[6] reported BTAIs managed with stent and open operation, and Yadavalli et al[22] analyzed the Vascular Quality Initiative, which accumulates data from operative patients only[22,23].

| Ref. | Design | Demographics | Details of BTAI | Management strategies | Primary and secondary outcomes |

| Kepros et al[29], 2002 | Retrospective, institutional | N = 5, mean age 365 years; 40% male | Aortic intimal tear (no further detail or grading) | Non-operatively | No mortality observed; 0% |

| Ott et al[6], 2004 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 18; n = 12 open vs n = 6 endo; median 43.5 endo vs 31.5 open, P = 0.18; 58.3% male open vs 66.7% male endo | Not mentioned | Endovascular vs open | In-hospital mortality: 0% endo vs 16.7% open, P = 0.53; paraplegia: 0% endo vs 16.7% open, P = 0.53; RLN injury: 0% endo vs 8.3% open, P = 1.00; ARDS: 0.0% vs 8.3%, P = 1.00; sepsis: 0.0% vs 41.67%, P = 0.11; MI: 0.0% vs 16.67%, P = 0.53; tracheostomy: 16.67% vs 33.33%, P = 1.00; arrhythmia: 33.33% vs 16.67%, P = 0.57; PE: 16.67% vs 8.33%, P = 1.00 |

| Hirose et al[1], 2005 | Retrospective, institutional data | N = 7; age 48.7 ± 22.7 years; 42.9% male | 3/7 intimal flap; 4/7 pseudoaneurysm | Non-operative | In-hospital mortality 14.2%; five-year survival 71.4%; of those that survive, 50% had stable disease, 50% had resolution |

| Stampfl et al[15], 2006 | Retrospective, institutional | n = 12; conservative (ages 41 and 76); surgery [age 30 (20-58)]; stent [age 47 (20-74)] | Local dissection, n = 8; contained rupture, n = 4 | Conservative (n = 2); surgery n = 5 (4 for rupture, 1 for dissection; stent n = 5 | No mortality in any group; surgery group: One return to OR; EVAR: One endoleak at 2 days, stented; no aortic reintervention in other patients or groups; no endoleaks in follow-up, mean follow-up 63 months (5-108) |

| Arthurs et al[3], 2009 | Retrospective, NTDB | N = 2402; age 41 ± 20 years; 42% male; NOM: n = 1642; age 42 ± 21 years; OAR: n = 665; age 39 ± 18 years; TEVAR: n = 95; age 41 ± 21 years | Data not available | 68% non-operative; 28% open; 4% endovascular | 30-day Mortality: 6.5% non-op vs 19% open vs 18% endovascular, P < 0.05; paraplegia: 0.3% vs 2% vs 1.6%; ARDS: 4% vs 7% vs 2%, P < 0.05; PNA 9% vs 18% vs 12%, P < 0.05; myocardial infarction: 22% vs 25% vs 4%, P < 0.05; acute renal failure: 3% vs 6% vs 10%, P < 0.05; stroke 02% vs 0.6% vs 1.6%, P = NS; ICU LOS: 11.5 ± 13 days vs 12 ± 12 days vs 13 ± 11 days, P = NS; hospital LOS: 12 ± 19 days vs 19 ± 20 days vs 23 ± 23 days, P < 0.05 |

| Caffarelli et al[30], 2010 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 53; Non-operative: n = 29; age 45 ± 15 years; 69.0% male; operative: n = 24; age 46 ± 20 years; 75% male | Non-op: 6 intimal injury; 2 IMH; 19 PSA | All non-op | 93% survival; no aortic deaths; 1 failed non-op; 2 had delayed repair at OSH after discharge; follow-up mean 107 days; median 31 days; 21 (78%) stable injuries; 5 (18%) complete resolution; 1 (4%) PSA progression |

| Mosquera et al[13], 2011 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 37 (conservative; age 44.2 ± 19.3) vs 22 surgical (age 30.8 ± 9.8) vs 7 endo (age 44.9 ± 13.8) | Transection: 24.3% conservative vs 86.4% surgical vs 85.8% endovascular; conservative: 40.5% IMH; 27.1% partial intimal tear; 8.1% PSA | In-hospital mortality: 21.6% conservative vs 22.7% surgical vs 14.3% endovascular (P = 0.57); aortic-related complications: 100% vs 0% vs 0%, P < 0.001; 1-year survival: 75.6% vs 77.2% vs 85.7%; 5-year survival: 72.3% vs 77.2% vs 85.7%, P = 0.59; no 10-year survival in endo group (suggests that long-term durability not known) | |

| Paul et al[28], 2011 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 47; (n = 15; 41.5 ± 13.9; 66.6% male non-op) vs operative (n = 19, open, 44.5 ± 23.7, 62% male; n = 13, endo, 45.2 ± 20; 79% male) | Operative repair; non-op; 2 false on angion; 2 PSA and 11 intimal tear | Non-op; 2 false; 5 resolved; 8 stable | Mortality: 10.6%; 5/32 in operative vs 0% in non-operative; follow-up imaging: Non-operative; 2 aortogram (-); 5 resolved; 8 stable |

| Mosquera et al[14], 2012 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 52; 9 patients MAI; 43 SAI | No formal grading; intimal tear < 10 mm MAI; rest SAI; PSA in SAI | 9 MAI; 100% conservative; 43 SAI (26 conservative; 9 open; 8 TEVAR) | In-hospital mortality: 22.2% MAI vs 30.2% SAI, P = 0.94; ICU LOS: 17.2 ± 16 days MAI vs 18.5 ± 14.2 days SAI, P = 0.81; one-year mortality 77.8% vs 69.6%, P = 0.46; five-year mortality: 77.8% vs 63.6%, P = 0.46; MAI: 6/7 resolution; 1 developed PSA |

| Kidane et al[5], 2013 | Retrospective, institutional | N = 59; non-op 43.4 (14.5) vs TEVAR 43.2 (21.8); non-op 53.6% male vs TEVAR 80.0% | Grades 1: 14 (27.0%); grade 2: 1 (1.9%); grade 3: 35 (67.3%); grade 4: 2 (3.8%) | Non-operative vs TEVAR; grade I: 13 NOM, I TEVAR; grade II: 1 NOM; grade III: 12 NOM, 23 TEVAR; grade IV: 2 TEVAR | Mortality: Non-operative 428% vs TEVAR 20.7% (not stratified by treatment type in each grade); grade I: 21.4% mortality; grade II: 0% mortality; grade III: 37.1% mortality; grade IV: 50% mortality |

| Rabin et al[27], 2014 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 97; 31 grade I; 35 grade II; 24 grade III; 7 grade IV | Grade I: 28/31 MM; 3 TEVAR; grade II: 13 MM; 11 TEVAR; grade III: 4 MM; 18 TEVAR; 2 open; grade IV: 5 open; 2 TEVAR | Grade I mortality: 10%; grade II: 20%; grade III: 21%; grade IV 29%; grade I: MM: 14.2% mortality vs 0% TEVAR; grade II: MM 46.2% mortality vs TEVAR 4.5% mortality; grade III: 5.6% TEVAR vs 0% OAR; grade IV: 50% TEVAR vs 80% OAR; follow-up: Grade I: 11 resolved; 5 unchanged; 2 small increases in injuries but no intervention (no aortic-related deaths, ruptures, complications); Grade II: 5 unchanged; 1 subsequent elective repair | |

| DuBose et al[20], 2015 | Retrospective; multi-institutional | N = 382; NOM, n = 123; age 447 ± 18.0 years; 32.5% male; operative, n = 259; age 404 ± 17.6 years; 24.7% male | Grade 1, 94; grade 2, 68; grade 3, 192; grade 4, 28 | Grade I: 76.6% NOM vs 5.3% OAR vs 18.1% TEVAR; grade II: 27.9% NOM vs 7.4% OAR vs 64.7% TEVAR; grade III: 12.5% NOM vs 21.9% OAR vs 65.1% TEVAR; grade IV: 25.0% NOM vs 32.1% OAR vs 42.9% TEVAR | NOM: 32%, 2 failures(1 grade I, 1 grade III); open repair in 61 patients (16%); TEVAR was done in 198 patients (52%). 6 patients of TEVAR failed, required 2 rpt TEVAR and 4 open repairs; overall in-hospital mortality 18.8% (NOM: 9.8%, OR: 13.1%, TEVAR: 2.5%); TEVAR was protective (P = 0.03); Aortic-related mortality 6.5%; 9.8% in NOM vs 5.0% P = 0.12; managed NOM grade I: 76.6%, grade II: 27.9%, grade III: 12.5%, grade IV: 25%. Failure rates: Grade I: 1.4%, grade II: 0%, grade III: 4.2%, grade IV: 0%; Managed w/TEVAR: Grade I: 18.1%, grade II: 64.7%, grade III: 65.1%, grade IV: 42.9%; failure rates: Grade I: 0%, grade II: 2.3%, grade III: 2.4%, grade IV: 16.7% |

| Gandhi et al[7], 2016 | Retrospective, institutional | N = 35 (17 TEVAR vs 18 NOM); 44 (23) TEVAR vs 47 (20) NOM; 64.7% male TEVAR vs 55.6% male non-op | Grade 3 | TEVAR vs non-operative | In-hospital mortality: 11.8% TEVAR vs 27.8% non-op, P = 0.402; aortic-related death 0% vs 6%, P = 1.00; any complications: 64.7% vs 50.0%, P = 0.728; AKI: 23.5% vs 22.2%, P = 1.00; PNA: 29.4% vs 22.2%, P = 0.711; respiratory failure: 17.6% vs 5.6%, P = 0.338; UTI: 17.6% vs 5.6%, P = 0.338; aortic injury; resolved/improved: 92.9% vs 87.5%, P = 0.674; worsened: 7.1% vs 12.5% |

| Tanizaki et al[17], 2016 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 18; age 58.2 years (24-88); 66.7% male | Grade III: 18 (100%) | Initial NOM for all | 22% mortality; 0% ARM; 14 patients followed non-operatively up for an average of 40.9 months; six grade III injuries were resolved; six grade III injuries were unchanged but did not require intervention; two patients in grade III had progression of pseudoaneurysm; 2/18 NOM required repair |

| Shackford et al[21], 2017 | Retrospective; multi-institutional | 255 patients total, TEVAR n = 176 (68%), age 46 years (28-60), 71% male; open n = 28 (10.8%), age 29 years (19-51); 71.4% male; NOM n = 51 (19.7%); age 42 (28-54); 64.7% male | No grading described | The overall In-hospital mortality was 5.9% (TEVAR 5.7%, Open 10.7%, NOM 3.9%. P = 0.535); 1 ARM in the TEVAR group; regarding the primary outcome of mortality, including In-hospital and post-discharge deaths, there was no significant difference between the three groups (TEVAR n = 12, 6.8%, Open n = 3, 10.7%, NOM n = 2, 3.9%, P = 0.485) | |

| Spencer et al[26], 2017 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 30; TEVAR 14; age 52 years (32-65); 79% male; NOM 16; 43 (37-66); 50% male | Grade I: 16; grade II: 14 | Grade I: 50%TEVAR; 50% NOM; grade II: 8 NOM; 6 TEVAR | TEVAR 14% mortality vs NOM 6%, P = NS; failure rate for grade 1-2 patients were 0%; all patients in the TEVAR group showed stable stents with no leak; 2 patients in the NOM group had progression(One from grade 1 to grade 2, one from grade 2 to grade 3), resolution in 3 grade 1 patients, and the remainder of 11 patients were stable |

| Sandhu et al[31], 2018 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 48; NOM; age 37.5 ± 15.1 years; 70.8% male; TEVAR grade II: 23; age 40.2 ± 14.3; 82.6% male | Grade I: 26; grade II:45 | Grade 1 26 NOM; grade II: 48.9% NOM vs 51.1% TEVAR | NOM: Overall 42% mortality (3.9% grade I; 4.6% grade II; 0% ARM); 71% had follow-up data; 84% resolved; 16% persistent injury; median injury resolution time was 39 days for grade 1 and 62 days for grade 2; TEVAR: 0% 30-day mortality |

| Gaffey et al[4], 2019 | Retrospective, institutional | N = 15; age 45 ± 20.6 years; 60% male | Grade II | Non-operative | 30-day mortality: 1/15; Five-year mortality: 2/15; follow-up CT 69 months (7-138); no repair performed; resolution: 73.3%; no change 26.7% |

| Dubose et al[19], 2021 | Prospectively collected; multi-institutional; registry | N = 296; age 44.5 ± 18 years; 76% male; NOM: n = 83 (28.0%); OAR n = 6 (2.0%); TEVAR n = 173 (58.4%) | Grade I n = 67 (22.6%), grade II n = 52 (17.6%), grade III n = 140 (47.3), grade IV n = 37 (12.5%) | Most of the patients underwent TEVAR (58.4%), Medical Management (28.0%), and open repair only 2%; I: 91% MM; 9% TEVAR; II: 61.5% MM; 38.5% TEVAR; III: 11.4% MM; 1.4% open; 86.4% TEVAR; IV: 2.7% MM; 10.8% open; 70.3% TEVAR | Overall mortality was 14.2% (42/296) (Table 1), with ARM at 4.7% (14/296) |

| For grade 1 and 2 patients, 59.7% managed medically, and 40.3% underwent TEVAR. No significant difference in aortic-related mortality for grade 1 and 2 injuries; I: 7.5% overall mortality; 1.5% ARM; II: 17.3% mortality; 1.9% ARM; III: 10% mortality; 1.4% ARM; IV: 37.8% mortality; 27.0% ARM | |||||

| McCurdy et al[24], 2020 | Single center; retrospective | N = 229; age 45.8 ± 19.7 years; 70.3% male; TEVAR: n = 61; 45.4 ± 15.7; 68.9% male; OAR: n = 66; 40.6 ± 20.0; 75.8% male; NOM: n = 102; 49.5 ± 19.7; 67.7% male | I: 69 (30.1%); II: 19 (8.3%); III: 69 (30.1%); IV: 72 (31.4%) | TEVAR vs OAR vs NOM; I: 5 vs 12 vs 52; II: 5 vs 1 vs 13; III: 29 vs 19 vs 21; IV: 22 vs 34 vs 16; overall: 44% NOM, 27%; TEVAR, and 29% OAR | Overall, 30-day mortality was 22%; NOM 30-day mortality: 8% for grade 1, 15% for grade 2, 48% for grade 3, and 94% for grade 4; TEVAR: 16% for grade I/II and 0% for grade III/IV; NOM 30%, 8.2% for the TEVAR group, and 21% for open surgery group |

| Madigan et al[25], 2022 | Retrospective; institutional | N = 176; NOM: n = 64; age 39 years (26-58); 28.1% female; TEVAR; n = 112; age 39 (26-58) years; 24.1% female | Grade I n = 36; grade II n = 24; grade III n = 115; grade IV n = 1 | 63.6% selected for TEVAR; grade I: 1/36; grade II 9/24; grade III 101/115; grade IV 1/1 | 30-day morbidity: 44.6% NOM vs 48.7% TEVAR, P = 0.64; 1-year mortality: 1.8% NOM vs 3.1% TEVAR, none of the NOM patients had progression; 44% resolution at follow-up; complete resolution of the aortic injury was seen in 28.6% of the grade 1 injuries and 20% of the grade 2 injuries at 30 days; remainder were stable; no progression 14 of grade 3 patients were treated NOM, most common reason to manage NOM was smaller size of PSA < 8 m without presence of peri-aortic hematoma, without proximal zone (Zone 0-1) lesion, and injuries in patients at extremes of age (< 18 or > 80). None of these lesions had progressed during follow-up, and one of the lesions resolved at 2-year follow-up |

| Sun et al[16], 2022 | Single-center 10-year retrospective study between 2013 and 2022 | N = 72 | Grade 1 = 1 (1.4%); grade 2 = 17 (23.6%); grade 3 = 52 (72.2%); grade 4 = 2 (2.8%) | Total 72 patients, 60 patients with/ TEVAR, 8 NOM, 4 open surgery; total all-cause mortality was 12.5%, aortic-related mortality was 4.2%; TEVAR patients were grade 2 ( n = 15) and 3 (n = 45), grade 3 patients had a higher rate of ICU admission (0% vs 13.3%) and similar in-hospital mortality (1.7% vs 5%) | |

| Al-Thani et al[18], 2022 | Retrospective observational study between 2000-2020; single center | N = 87; NOM: Age 40.6 ± 16.4 years; 97.1% male; OAR: Age 37.1 ± 10.9 years; 47.4% male; TEVAR: 34.1 ± 13.8; 84.8% male | Grade 1 10 (11.5%); grade 2 12 (13.8%); grade 3 36 (41.4%); Grade 4 29 (33.3%) | 40% NOM n = 35; 60% treated operatively n = 52; TEVAR 33 patients (63.5%); open surgery 19 patients (36.5%); grade I: 10 NOM; grade II: 12 NOM; grade III: 4 NOM vs 10 OAR vs 22 stent; grade IV: 9 NOM vs 9 OAR vs 11 stent | Overall, in-hospital mortality was 25.3%; significantly higher in-hospital mortality in the conservative group (40%), compared to open surgery (31.6%) and TEVAR (6.1%); TEVAR patients n = 33; grade I: 0% mortality; grade II: NOM 25% mortality; grade III: 50% NOM vs 20% OA vs 45% stent; grade IV: 100% NOM vs 44.4% OAR vs 9.1% stent |

| Arbabi et al[12], 2022 | Prospective, multi-institutional; aortic trauma foundation | N = 432; NOM: n = 114; 38.5 (29); 69.3% male; intervention; n = 318, age 45 years (IQR 29); 78.3% male | Grade I 102; grade II 62; grade III 221; grade IV 47 | 114 patients underwent MM; 68 (59.6%) grade 1, 27 (23.7%) grade II, 18 (15.8%) grade III and 1(0.9%) grade IV; intervention: Grade I 34 (10.7%), grade II 35 (11.0%), grade III 203 (60.8%), grade IV 46 (14.5%) | 12/114 required intervention; with 11 undergoing TEVAR and 1 open; grade I 1.5% failure rate; grade II 0% failure rate; grade III 55.5% failure rate; grade IV 100% failure rate; 30-day mortality rate of 1.7%; in-hospital mortality rate of 7.9%; no aortic-related mortality |

| Ye et al[11], 2022 | Retrospective, institutional | N = 12, age 60 (16.1) years, 50% male | Grade 2 n = 2; grade 3 n = 10 | NOM: n = 7; TEVAR n = 5; median 2 days | Mortality: 0% vs 40%, P = 0.182; LOS: 41.5 (17.5-69.0) vs 3.0 (1.5-38.5), P = 0.177 |

| Yadavalli et al[22], 2023 | Retrospective cohort, collected data from VQI, between 2013 to 2022 | N = 1311 | Grade 1 = 106 (8%); grade 2 = 244 (19%); grade 3 = 741 (57%); grade 4 = 220 (17 %) | All patients underwent TEVAR | Primary outcomes were peri-op (within 30 days) and 5-year mortality; higher grades with higher mortality overall (grade 1: 6.6%, grade 2: 4.9 %, grade 3: 7.2%, grade 4 14%); 5-year mortality rates were higher with grade 4 as well. (grade 1 11%, grade 2: 10%, grade 3 11%, and grade 4: 19%) |

| Golestani et al[23], 2024 | Retrospective analysis of Aortic Trauma Foundation (Multicenter Registry) | N = 269 | Grade 1 186; grade 2 83 | 218 patients Non-operative; 51 TEVAR | There was a significant difference in mortality between NOM alone and TEVAR (8% vs 18% P = 0.009); patients with/TEVAR increased incidence of DVT( 12% vs 1%, P = 0.002); hospital and ICU length of stay were not different |

Basic demographics, such as age and sex of participating patients, were included in almost all studies and are included in Table 1 where available. Only sixteen studies adhered to SVS reporting standards for classification of BTAI. Three studies did not provide any description of the BTAIs reported[3,6,21]. Of the sixteen studies that adhered to SVS standards, nine studies included patients with all BTAI grades[5,12,16,18-20,22,24,25]. Three studies included patients with grade I and II BTAI only, while one study focused on grade II and III BTAI[11,21,23,26]. Gandhi et al[7] and Tanizaki et al[17] included only grade III BTAI, while Gaffey et al[4] included only grade II BTAI. Eight studies utilized non-standardized reporting standards for describing BTAIs[1,13-15,27-30]. Kepros et al[29] described their sample as patients with aortic intimal tear, while Stampfl et al[15] classified them as local dissections and contained rupture. Rabin et al[27] utilized a non-standardized grading system for classifying BTAI. Other authors classified BTAI using broad categories such as intimal tear, intramural hematoma, length of intimal disruption, and pseudoaneurysm[1,13-15,28-30].

A total of 2792 patients were managed non-operatively, and 3698 patients received intervention as the initial management. Mortality was the most frequently reported outcome across the studies included. Amongst authors that did not provide any distinct BTAI classification, Ott et al[6] reported a higher mortality in patients undergoing open repair compared with endovascular repair (16.7% open vs 0.0% endovascular, P = 0.53), consistent with Arthurs, who also noted significantly lower mortality in the NOM group (6.5% NOM vs 19% open vs 18% endovascular, P < 0.05)[3,6]. Conversely, Shackford et al did not note any difference in mortality across these groups (3.9% NOM vs 5.7% TEVAR vs 10.7% open aortic repair, P = 0.535)[21].

Stampfl et al[15] and Kepros et al[29] did not report any mortality across their study samples of BTAI patients. Hirose et al[1] did reported a 14.2% in-hospital mortality rate in their study. All deaths occurring in Caffarelli et al’s analysis were prior to the decision to intervene vs manage conservatively[30]. Mosquera et al[13] found a trend towards a higher rate of mortality in the significant aortic injury patients compared with minimal aortic injury (30.2% vs 22.2%, P = 0.94), however, in their second analysis, did not find any differences across different treatment modalities (21.6% NOM vs 22.7% open vs 14.3% endovascular, P = 0.53)[13,14]. Rabin et al[27] did find increasing mortality with higher grade of injury, and in the data on grade II BTAI, they reported 46.2% mortality with NOM compared with 4.5% mortality in the TEVAR group. There were no patients undergoing NOM in the grade III or grade IV group.

Although some studies followed SVS standards for BTAI grade classification, their reported outcomes were not stratified by both grade and treatment type. These studies did demonstrate a trend of increasing mortality with increasing grade[5,19,20,25]. Of note, in all of these studies, the ARM was minimal, with most deaths being attributed to other traumatic causes. Only DuBose et al[19] reported ARM by BTAI grade, and showed a very high proportion of ARM in grade IV injury (27.0% in grade IV compared with 1.4%-1.9% in grades I to III). Yadavalli et al[22] found a higher mortality rate with increasing BTAI grade in their Vascular Quality Initiative analysis of post-stent patients (Grade I 6.6% vs grade II 4.9% vs grade III 7.2% vs grade IV 14.0%, P = 0.003). Authors who analyzed only low-grade BTAI (I and II) found mortality rates of 4.2% to 8.0% in the non-operative arm and 14%-18% in the endovascular arm[4,23,26,31]. For grade III BTAI, in-hospital mortality ranged from 22% to 28% in the non-operative group and was 12% in the TEVAR group[7,17].

Some studies also reported rates of unplanned intervention for BTAI patients after failure of medical management. Both endovascular and surgical repair techniques were employed after the initial trial of NOM. Arbabi et al[12] did not define their criteria for repair, but Tanizaki et al[17] and DuBose et al[20] selected NOM patients who had progression on imaging for repair. DuBose et al[20] reported very low failure rates across all BTAI grades (grade 1: 1.4%, grade 2: 0%, grade 3: 4.2%, and grade 4: 0%), however Arbabi et al[12] found very high rates of intervention among high-grade BTAI patients (Grade I: 1.5%, grade II: 0%, grade III: 55.5%, and grade IV: 100%)[12,20]. Spencer et al[26] and Rabin et al[27] found very low intervention rates in their series of low-grade BTAI patients, 9.1% and 0% respectively. Per Tanizaki et al[17], 11% of grade III BTAI patients required repair after follow-up assessment.

Only 11 of the 27 studies had any imaging follow-up after the initial hospitalization. Most patients had stable or resolving disease on follow-up. Follow-up duration varied widely. Spencer et al[26] only followed patients till discharge, while other groups, such as Caffarelli et al[30] and Paul et al[28], had up to one year of imaging follow-up[1,26,28,30]. Few authors had an average follow-up in years[1,7,15,17,25]. Hirose et al[1] found that among survivors, 50% had stable BTAI while the rest had resolution of injury. Stampfl et al[15] did provide data on the lack of endoleaks on follow-up, but did not comment on BTAI grade. Among authors that did not adhere to SVS reporting standards, most patients had stable disease on follow-up, some had resolution of BTAI, and a small percentage experienced progression of disease, ranging from 0% to 14%[14,27,28,30]. In their studies pertaining to grade I and II BTAI, only Gaffey et al[4] found a 12.5% progression of disease, while Spencer et al[26] and Sandhu et al[31] did not find any progression. Resolution rates varied as well, with Gaffey et al[4] and Sandhu et al[31] reporting rates of 73% to 84% of resolution, while Spencer et al[26] reported only 18.8% resolution. Gandhi et al[7] and Tanizaki et al[17] found similar incidence of progression of pseudoaneurysm on imaging follow-up, 13% and 11% respectively.

Our review of the literature collected the published data over the past two decades in the management of BTAI. We evaluated multiple studies and included 7490 patients who were treated non-operatively or with endovascular or surgical techniques. Firstly, the data showed that low-grade BTAI could be managed non-operatively with lower mortality; however, higher-grade BTAI was associated with greater mortality. Secondly, even after NOM, the rates of delayed intervention were low for grade I and II BTAI, and variable for grade III BTAI. Lastly, limited data were available on imaging follow-up, but most low-grade I/II lesions did not progress, with a small percentage even undergoing resolution.

Given the high-energy mechanisms associated with BTAI, other injuries are frequently present and may confound the mortality from the aortic pathology itself. It is well-reported that this disease process is the second most common cause of death associated with blunt trauma[8]. Given that lower mortality rates were observed with endovascular repair, there has been a shift from surgical repair to less invasive options over the past two decades as endovascular therapies are increasingly adopted into the practice pattern of vascular surgeons. In a similar trend, as the spectrum of disease has been more clearly defined into varying grades, medical management has also been shown to be successful for select patients. In our review, we noted that more dated papers did not utilize standardized terminology to describe the injuries, and classified patients into categories such as “minimal aortic injury” and “significant aortic injury”[14]. Other characteristics, such as intimal tear, intimal disruption, intramural hematoma, and localized dissection, have been used without any consistent definition[1,6,15,29]. While a large volume of data may have been published on the matter, our study showed that only sixteen of the twenty-seven studies included adhered to SVS reporting standards.

In our review, while mortality did increase with grade, lower rates of in-hospital mortality were observed in NOM compared with surgical or endovascular repair in low-grade BTAI. Earlier studies did note limited mortality with NOM; however did not stratify by grade[21]. Among analyses stratified by BTAI grade, higher mortality was observed in higher grade injury as expected across all treatment groups[20,22]. Several authors showed that for grades 1 and 2 BTAI, mortality rates were lower among the NOM group, ranging from 4.2% to 8.0%, compared with the endovascular group, with rates of 14% to 18%[4,23,26,31]. A few studies also explored NOM for grade III BTAI or pseudoaneurysm. Gandhi et al[7] showed an 11.8% in-hospital mortality in the TEVAR group compared with 27.8% in the NOM group; however, this did not meet significance. Tanizaki et al[17] only studies grade III injuries that were managed non-operatively and demonstrated an in-hospital mortality rate of 22%, but deaths were attributed to other non-aortic causes, suggesting that there is a role for endovascular management in this subgroup. Harris et al[32] in their review of traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm, found that factors such as the diameter ratio may be used to predict stability and safety of NOM.

NOM for BTAI is associated with intensive care unit stay, strict blood pressure monitoring and control, and follow-up imaging. Progression of aortic injury despite rigorous blood pressure control, onset of hemodynamic instability, or development of symptoms may lead the team to intervention. Some patients may require intervention after a short trial of medical management. Per DuBose et al[20] and their review of multi-center data, less than 5% of patients in any grade required delayed repair, while in contrast, Arbabi et al[12] showed a grade-dependent increase in failure rates. While all authors who had sufficient follow-up found low rates of repair needed in grade I and II BTAI after NOM, a wide range of intervention rates were reported for grade III BTAI from 11% up to 55%[12,17]. Further data is needed to understand the natural history of the traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm and factors that may influence growth or resolution.

Given the transient nature of the trauma population and several factors inhibiting follow-up, less than half of the reviewed studies included follow-up with CT imaging. Moreover, due to a lack of guidelines as well as limited understanding of the natural progression of non-operatively managed BTAI, there is significant variation in follow-up. Nonetheless, several studies demonstrated that there is a low rate of progression of BTAI that has been non-operatively managed. Even in older studies, such as those by Hirose et al[1] and Caffarelli et al[30], they reported 50% to 78% of patients had stable disease and 18% to 50% had resolution within the first year. Gandhi et al[7] showed a very low rate of worsening BTAI grade during treatment, with no difference by treatment arm (7.1% at 2.6 years follow-up in the TEVAR group vs 12.5% at 0.8 years in the NOM group, P = 0.674). In fact, both Madigan et al[25] and Sandhu et al[31] did not show any progression of low-grade BTAI on follow-up). Tanizaki et al[17] showed a very low rate of progression of grade III BTAI on follow-up, with only 2 of 14 available patients having worsening of the pathology. Overall, a percentage of patients exists who may experience worsening aortopathy after successful management, hence regular follow-up is necessary.

Our study is limited in that it is a retrospective review of published data, and hence, there are differences in the patient populations being compared. Given that the published data is not necessarily stratified by grade, there is limited granular data related to grade II BTAI, and minimal data has been published focusing on grade III BTAI, strong recommendations cannot be made without larger studies. Moreover, given that we have included studies both before and after the SVS reporting guidelines were published, there is variation in the language used to describe BTAI. Not all studies defined the reason behind the provider’s decision to abandon medical management for endovascular or open repair. Given that most follow-up is per provider discretion and patient factors, imaging data after discharge is sparse. Lastly, given the heterogeneity of the studies included, meta-analysis was not conducted, limiting the statistical robustness of our findings.

This review article provides the most up-to-date literature. Currently literature supporting the NOM for low-grade BTAI (grades I and II) treatment. Current SVS guidelines recommend endovascular repair for grade III BTAI patients; however, a few studies showed that grade III BTAI can be managed non-operatively with active surveillance in a selected group of patients. Literature requires further studies to compare NOM vs endovascular repair in higher-grade BTAI population

| 1. | Hirose H, Gill IS, Malangoni MA. Nonoperative management of traumatic aortic injury. J Trauma. 2006;60:597-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Harris DG, Rabin J, Starnes BW, Khoynezhad A, Conway RG, Taylor BS, Toursavadkohi S, Crawford RS. Evolution of lesion-specific management of blunt thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:500-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arthurs ZM, Starnes BW, Sohn VY, Singh N, Martin MJ, Andersen CA. Functional and survival outcomes in traumatic blunt thoracic aortic injuries: An analysis of the National Trauma Databank. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:988-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gaffey AC, Zhang J, Saka E, Quatromoni JG, Glaser J, Kim P, Szeto W, Kalapatapu V. Natural History of Nonoperative Management of Grade II Blunt Thoracic Aortic Injury. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kidane B, Parry NG, Forbes TL. Review of the management of blunt thoracic aortic injuries according to current treatment recommendations. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:1014-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ott MC, Stewart TC, Lawlor DK, Gray DK, Forbes TL. Management of blunt thoracic aortic injuries: endovascular stents versus open repair. J Trauma. 2004;56:565-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gandhi SS, Blas JV, Lee S, Eidt JF, Carsten CG 3rd. Nonoperative management of grade III blunt thoracic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64:1580-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee WA, Matsumura JS, Mitchell RS, Farber MA, Greenberg RK, Azizzadeh A, Murad MH, Fairman RM. Endovascular repair of traumatic thoracic aortic injury: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mouawad NJ, Paulisin J, Hofmeister S, Thomas MB. Blunt thoracic aortic injury - concepts and management. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lozano R, DiLosa K, Schneck M, Maximus S, Callcut R, Shatz D, Mell M. Comparison of treatment and outcomes in blunt thoracic aortic injury based on different vascular surgery guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2023;78:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ye JB, Lee JY, Lee JS, Kim SH, Choi H, Kim Y, Yoon SY, Sul YH, Choi JH. Observational management of Grade II or higher blunt traumatic thoracic aortic injury: 15 years of experience at a single suburban institution. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2022;12:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arbabi CN, Dubose J, Charlton-Ouw K, Starnes BW, Saqib N, Quiroga E, Miller C, Azizzadeh A. Outcomes and practice patterns of medical management of blunt thoracic aortic injury from the Aortic Trauma Foundation global registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63:e22-e23. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mosquera VX, Marini M, Lopez-Perez JM, Muñiz-Garcia J, Herrera JM, Cao I, Cuenca JJ. Role of conservative management in traumatic aortic injury: comparison of long-term results of conservative, surgical, and endovascular treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:614-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mosquera VX, Marini M, Gulías D, Cao I, Muñiz J, Herrera-Noreña JM, López-Pérez JM, Cuenca JJ. Minimal traumatic aortic injuries: meaning and natural history. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:773-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stampfl P, Greitbauer M, Zimpfer D, Fleck T, Schoder M, Lammer J, Wolner E, Grimm M, Vécsei V, Czerny M. Mid-term results of conservative, conventional and endovascular treatment for acute traumatic aortic lesions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sun J, Ren K, Zhang L, Xue C, Duan W, Liu J, Cong R. Traumatic blunt thoracic aortic injury: a 10-year single-center retrospective analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;17:335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tanizaki S, Maeda S, Matano H, Sera M, Nagai H, Nakanishi T, Ishida H. Blunt thoracic aortic injury with small pseudoaneurysm may be managed by nonoperative treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Al-Thani H, Hakim S, Asim M, Basharat K, El-Menyar A. Patterns, management options and outcome of blunt thoracic aortic injuries: a 20-year experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:4079-4091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | DuBose JJ, Charlton-Ouw K, Starnes B, Saqib N, Quiroga E, Morrison J, Gewertz B, Azizzadeh A; AAST/Aortic Trauma Foundation Study Group. Do patients with minimal blunt thoracic aortic injury require thoracic endovascular repair? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DuBose JJ, Leake SS, Brenner M, Pasley J, O'Callaghan T, Luo-Owen X, Trust MD, Mooney J, Zhao FZ, Azizzadeh A; Aortic Trauma Foundation. Contemporary management and outcomes of blunt thoracic aortic injury: a multicenter retrospective study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:360-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shackford SR, Dunne CE, Karmy-Jones R, Long W 3rd, Teso D, Schreiber MA, Watson J, Watson C, McIntyre RC Jr, Ferrigno L, Shapiro ML, Southerland K, Dunn JA, Reckard P, Scalea TM, Brenner M, Teeter WA. The evolution of care improves outcome in blunt thoracic aortic injury: A Western Trauma Association multicenter study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:1006-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yadavalli SD, Romijn AC, Rastogi V, Summers SP, Marcaccio CL, Zettervall SL, Eslami MH, Starnes BW, Verhagen HJM, Schermerhorn ML. Outcomes following thoracic endovascular aortic repair for blunt thoracic aortic injury stratified by Society for Vascular Surgery grade. J Vasc Surg. 2023;78:38-47.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Golestani S, Dubose JJ, Efird J, Teixeira PG, Cardenas TC, Trust MD, Ali S, Aydelotte J, Bradford J, Brown CV. Nonoperative Management for Low-Grade Blunt Thoracic Aortic Injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238:1099-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McCurdy CM, Faiza Z, Namburi N, Hartman TJ, Corvera JS, Jenkins P, Timsina LR, Lee LS. Eleven-Year Experience Treating Blunt Thoracic Aortic Injury at a Tertiary Referral Center. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Madigan MC, Lewis AJ, Liang NL, Handzel R, Hager E, Makaroun MS, Chaer RA, Eslami MH. Outcomes of operative and nonoperative management of blunt thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2022;76:239-247.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Spencer SM, Safcsak K, Smith CP, Cheatham ML, Bhullar IS. Nonoperative management rather than endovascular repair may be safe for grade II blunt traumatic aortic injuries: An 11-year retrospective analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rabin J, DuBose J, Sliker CW, O'Connor JV, Scalea TM, Griffith BP. Parameters for successful nonoperative management of traumatic aortic injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Paul JS, Neideen T, Tutton S, Milia D, Tolat P, Foley D, Brasel K. Minimal aortic injury after blunt trauma: selective nonoperative management is safe. J Trauma. 2011;71:1519-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kepros J, Angood P, Jaffe CC, Rabinovici R. Aortic intimal injuries from blunt trauma: resolution profile in nonoperative management. J Trauma. 2002;52:475-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Caffarelli AD, Mallidi HR, Maggio PM, Spain DA, Miller DC, Mitchell RS. Early outcomes of deliberate nonoperative management for blunt thoracic aortic injury in trauma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sandhu HK, Leonard SD, Perlick A, Saqib NU, Miller CC 3rd, Charlton-Ouw KM, Safi HJ, Azizzadeh A. Determinants and outcomes of nonoperative management for blunt traumatic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67:389-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Harris DG, Rabin J, Bhardwaj A, June AS, Oates CP, Garrido D, Toursavadkohi S, Khoynezhad A, Crawford RS. Nonoperative Management of Traumatic Aortic Pseudoaneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;35:75-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/