Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.114575

Revised: October 8, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 91 Days and 15.8 Hours

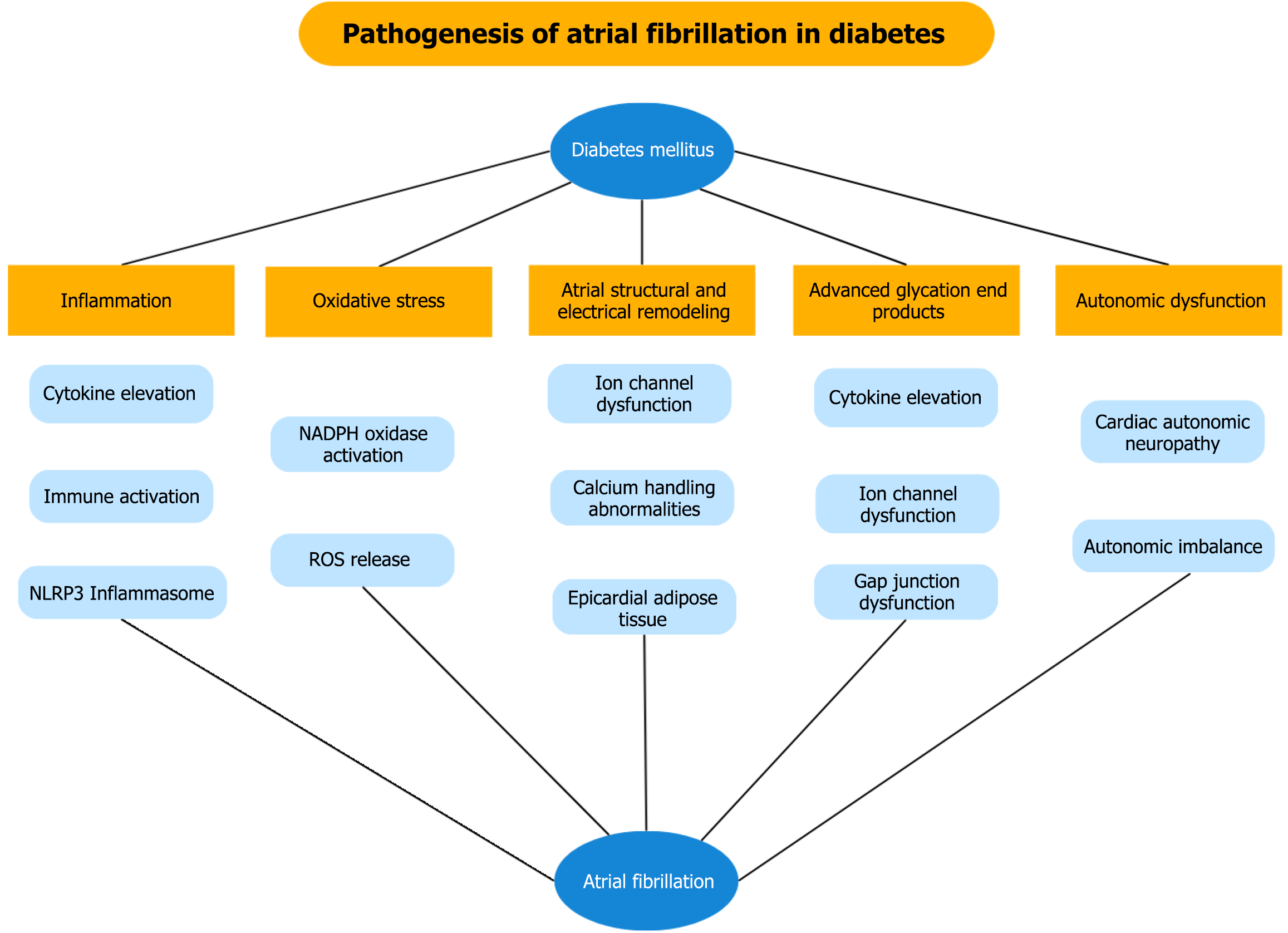

Diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation (AF) are two global epidemics that frequently coexist, with diabetes mellitus contributing to both an increased risk of new-onset AF and a worse prognosis. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this relationship include chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, atrial remodeling, autonomic dysfunction, advanced glycation end-products and epicardial adipo

Core Tip: Diabetes and atrial fibrillation are closely related conditions that increase cardiovascular risk through shared mechanisms of metabolic dysfunction, inflammation and atrial remodeling. Their coexistence complicates treatment decisions, yet novel strategies are reshaping care. Beyond optimized anticoagulation and rhythm control, emerging antidiabetic agents show promise in improving outcomes. This comprehensive review highlights current evidence, evolving therapies and the need for individualized management to reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality in this population.

- Citation: Karanikola AE, Tsiachris D, Argyriou N, Botis M, Pamporis K, Xydis P, Fragoulis C, Kordalis A, Tsioufis K. Complex interrelationship and therapeutic advances in diabetic patients with atrial fibrillation. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 114575

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/114575.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.114575

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most prevalent metabolic conditions, with type 2 DM affecting approximately 8.9% of the United States population and up to 14% of the global population, with continued increases especially in low- and middle-income countries[1,2]. In 2021, more than 500 million people globally were living with type 2 DM and this number is projected to rise substantially by 2050, driven by population growth, aging, obesity, hyperglycemia and environmental factors such as pollution[3]. DM is a major cardiovascular risk factor, closely linked to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and heart failure and is additionally associated with higher rates of cardiovascular events and mortality[4].

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in adults, with prevalence rising steadily over recent decades[5]. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving atrial structural and electrical remodeling, inflammation, oxidative stress and autonomic imbalance[6-8]. DM is associated not only with an increased risk of new-onset AF but also contributes to suboptimal arrhythmia control and poor prognosis in patients with AF[9]. Although the precise me

Literature for this narrative review was identified through PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science using Boolean operators and combinations of terms such as “diabetes”, “atrial fibrillation”, “pathophysiology”, “prognosis”, “antiarrhythmic drugs”, “antidiabetic medications”, “catheter ablation”, and “stroke risk.” Articles published in English between 2015 and 2025 were primarily considered, with older landmark studies included when relevant. Both original research and review articles were incorporated to provide a comprehensive overview. Titles and abstracts were screened, and citation tracking (snowballing) was used to identify additional relevant studies, with all references managed in a reference manager. The review focuses on studies most relevant to the clinical, mechanistic and therapeutic aspects of AF in patients with DM.

Given the high prevalence of both AF and DM in the general population, their frequent coexistence is expected. Approximately one in five patients with AF has DM and DM confers roughly a threefold higher risk of AF in a large population study[12,13]. One of the first epidemiological studies linking DM to an increased risk of AF was the Framingham Heart Study, with later studies demonstrating similar results[14,15]. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, which included 15792 middle-aged white and African American participants from the United States, showed that DM was independently associated with a 35% higher risk of AF after adjustment for multiple risk factors[16]. A pooled analysis showed that DM was associated with a markedly elevated risk of AF, about 50% higher than in individuals without DM, which decreased to roughly 23% after adjusting for hypertension, obesity and structural heart disease; this increased risk was consistent across DM subtypes, more pronounced in women than men and has risen progressively over time[17]. In the ACCORD trial, new-onset AF occurred among 10251 individuals with DM at a rate of 5.9-6.37 per 1000 patient-years, depending on the intensity of glycemic control and was independently predicted by older age, higher weight, lower diastolic blood pressure, lower heart rate and prior heart failure, while being associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes[18].

In addition, evidence suggests that DM duration and poor glycemic control seem to affect the risk of AF. In a population-based case-control study of 311 diabetic patients, longer duration of DM was linked to a steadily increasing risk of AF, with each additional year raising the risk by approximately 3%. Importantly, poor glycemic control [glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels > 9] appeared to nearly double the risk[19]. Similarly, in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, each 1% increase in HbA1c levels was associated with a 13% higher risk of AF, highlighting the pivotal role of glycemic control in AF outcomes[16].

DM is not only a risk factor for the development of AF but is also associated with worse outcomes and more rapid AF progression. Large registries and cohort studies consistently show that patients with DM experience poorer outcomes in AF. In the ORBIT-AF registry, DM independently predicted higher risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, hospitalizations, AF-related symptoms, and incident heart failure, despite similar stroke rates, likely reflecting widespread anticoagulation use[9]. Likewise, the EORP-AF registry reported that diabetic patients with AF experienced more thromboembolic and coronary events, as well as greater all-cause mortality at 12-month follow-up, compared with non-diabetic patients[20]. The ADVANCE study further demonstrated that, among patients with DM, AF conferred a nearly 1.8-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality and a 1.7-fold higher risk of heart failure[21]. Evidence from a large South Korean cohort of 65760 patients with DM showed that those with AF had a greater burden of macrovascular complications, an approximately 25% higher risk of diabetic nephropathy, and a modestly higher incidence of diabetic foot compared with those without AF[22]. Similarly, Taiwanese data in 3600 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease revealed increased risks of cerebrovascular events, heart failure and mortality in the presence of AF[23]. Silent AF is also prevalent in this population; in the SWISS-AF study, DM was linked to less symptomatic AF but worse quality of life and higher prevalence of cardiac and neurological comorbidities, while the NOMED-AF study showed significantly higher rates of subclinical AF among diabetic individuals, who also more frequently had persistent or permanent AF (12.2% vs 6.9% in non-diabetic patients)[24,25]. Furthermore, AF appears to progress more rapidly in patients with DM, with a meta-analysis of 20 studies showing both a higher likelihood of non-paroxysmal AF [pooled odds ratio = 1.31, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.13-1.51; I2 = 82.6%] and an increased risk of progression from paroxysmal to non-paroxysmal AF (pooled odds ratio = 1.32, 95%CI: 1.07-1.62; I2 = 0%), compared with non-diabetic individuals[26]. Given the high prevalence of AF among patients with DM and the associated excess morbidity and mortality, the 2023 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines strongly recommend opportunistic AF screening, via pulse checks and serial electrocardiogram recordings, even in younger patients under 65 years of age[27].

Several mechanisms of AF initiation and progression in diabetic patients have been described, including inflammation and epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) formation, cardiac fibrosis, cardiac autonomic neuropathy, abnormal calcium handling and changes in voltage-gated channels, as a result of insulin resistance-associated metabolic abnormality[28]. A schematic representation of these mechanisms is shown in Figure 1.

In DM, both systemic and local inflammation promote AF by elevating cytokines, chemokines, and innate immune activation, as shown by increased monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β and macrophage infiltration in atrial tissue[29,30]. Experimental studies have also indicated that activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells pathway and the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing the 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome further contributes to adverse structural remodeling, Ca2+-handling abnormalities, and increased AF vulnerability in diabetic hearts[31-33].

Oxidative stress is a key contributor to AF pathogenesis, as mitochondrial reactive oxygen species release in the atria activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and promotes Ca2+-handling abnormalities, electrical remodeling and increased arrhythmogenicity[34,35]. In a rabbit model of DM, NADPH oxidase activation was linked to increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, structural and electrical atrial remodeling through atrial enlargement and a reduction in atrial mean conduction velocity, effects that increase AF induction[36]. Inhibition of oxidative stress molecules, including NADPH oxidase and xanthine oxidase, have been associated with reduced arrhythmogenicity in patients with DM[37,38].

DM promotes atrial electrical remodeling by altering sodium, calcium, potassium and other ion channel functions, leading to abnormal action potentials, conduction slowing, prolonged refractoriness and increased susceptibility to AF[39]. Evidence derives mostly from experimental animal studies. Bohne et al[40] demonstrated that mice with type 2 DM exhibited prolonged P-wave duration times, biatrial action potential duration prolongation and reduced outward IK current during sinus rhythm, leading to increased AF inducibility and duration after burst pacing. Similar results were reported by Polina et al[41], who indicated that mice with type 1 DM had reduced INa and peak IK currents along with decreased SCN5a expression, promoting AF susceptibility, while chronic insulin therapy partially restored those effects.

Abnormal calcium handling has been recognized as a mediator of cardiac structural remodeling, leading to proarrhythmic effects through regulation of ion channels[42]. Calpain is a Ca2+-activated protease that regulates calcium metabolism and has been shown to increase AF susceptibility[43]. Animal studies have shown that calpain is overexpressed in diabetic atria, leading to abnormal calcium induced-calcium release and increased arrhythmogenicity[44].

Autonomic dysfunction, particularly cardiac autonomic neuropathy, is a common and well-recognized complication of DM. The prevalence of cardiac autonomic neuropathy varies and has been reported up to 66% in type 1 DM, whereas in type 2 DM it can reach as high as 73% and is increasing with advancing age and DM duration[45]. It has long been established that sympathetic and parasympathetic activation, along with autonomic remodeling, play a critical role in regulating atrial cellular electrophysiology, thus initiating and sustaining AF through enhanced automaticity, early afterdepolarizations and triggered activity[46]. Autonomic imbalance, measured by heart rate variability parameters, has been significantly associated with a higher incidence of subclinical AF episodes in patients with type 2 DM[47]. Additionally, experimental studies have demonstrated that DM may lead to autonomic dysregulation of the heart through structural remodeling and reduction in the size of cardiac ganglia, including those located in the pulmonary veins[48,49].

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are molecules formed by non-enzymatic reactions between sugars and proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids. Chronic accumulation in blood and tissues may contribute to the development of diabetic complications by triggering inflammatory signals and oxidative stress[50]. In experimental models, AGEs promote fibroblast-driven inflammation via interleukin-6, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 through the receptor of AGE (RAGE)-mitogen-activated protein kinase-nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells pathways[51]. AGE-mediated remodeling has also been associated with atrial fibrosis and dilation in AF patients[52]. In addition, reduced levels of soluble RAGE (sRAGE), a molecule found in plasma that can act as a RAGE inhibitor, have been linked with higher baseline inflammation in diabetic patients[53].

Apart from inducing inflammation, AGEs seem to interfere with atrial electrophysiology as well. AGEs activate the RAGE pathway in diabetic atrial tissue, leading to reduced ICa, L and IKur currents via the p16/Rb signaling pathway, while inhibition of AGEs/RAGE and its downstream p16/Rb signaling mitigates atrial electrophysiological remodeling and decreases AF inducibility in diabetic mice[54]. Increased AGEs in diabetic rats also downregulate atrial connexin 43 and connexin 40, leading to impaired gap junction function, which has been associated with AF induction, while AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation can restore their expression and electrical coupling[55]. Evidence from human studies also suggested that in diabetic patients, upregulation of RAGE increases late sodium current (INaL), leading to prolonged action potential duration, while RAGE silencing reverses these changes, suggesting a key role of RAGE-mediated electrical remodeling in AF development[56].

EAT increases with obesity and DM, where it contributes to insulin resistance, ion channel dysfunction and inflammasome activation, leading to cardiac remodeling and fibrosis[57-59]. Increased EAT mass and volume are independent predictors of AF[60,61]. A recent study using bioinformatics has shed light on EAT-related molecular pathways, identifying more than 100 genes involved in immune regulation and energy metabolism as key mediators linking type 2 DM and AF[62].

The 2024 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the management of AF introduced the updated AF-CARE, a comprehensive and universal approach to AF treatment[63]. In the case of DM, the AF-CARE pathway emphasizes proper glycemic control, stroke and thromboembolism prophylaxis, tailored rate and rhythm control strategies and continued evaluation of disease progression.

Stroke prevention: DM is a well-recognized predisposing factor for systemic thromboembolism and stroke, a risk reflected in its inclusion in widely used clinical risk scores such as CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VA[63,64]. Current society guidelines provide a class I recommendation for the use of anticoagulation in patients with DM and non-valvular AF. Importantly, even in patients with DM but without additional stroke risk factors, anticoagulation carries a class IIa recommendation, reflecting the recognition of DM itself as a strong contributor to thromboembolic risk[27]. The type of DM may also be relevant, as data from a Danish cohort suggested that younger patients with type 2 DM are at higher risk of thromboembolism compared with patients under 65 years of age with type 1 DM[65].

The presence of DM generally does not affect the choice of anticoagulant, with non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) being the preferred option, similar to the general population. In subanalyses of the ROCKET-AF and the ARISTOTLE trials, rivaroxaban and apixaban, respectively, consistently reduced stroke, systemic embolism, mortality and bleeding events compared with warfarin in patients with and without DM[66,67]. A meta-analysis of the four pivotal trials on NOACs (RE-LY-dabigatran, ROCKET-AF-rivaroxaban, ARISTOTLE-apixaban, and ENGAGE AF-edoxaban) demonstrated that NOACs protected against thromboembolic and bleeding events regardless of DM status, with a greater absolute reduction in vascular death observed among those with DM[68]. This added benefit of anticoagulation on diabetic patients has been investigated in other studies as well. In the case of rivaroxaban, Baker et al[69] reported a 63% reduction in major adverse limb events in patients with DM and peripheral arterial disease without an increase in major bleeding events. In a large United States cohort of patients with non-valvular AF and DM, rivaroxaban was associated with a significant reduction in both acute and stage 5 chronic kidney injury or need for hemodialysis compared with warfarin, possibly through anti-inflammatory effects of Factor Xa inhibition on renal vasculature[70].

Given the multiple interactions of anticoagulants with cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) function, caution should be taken when administering specific glucose-lowering medications or antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) in this subpopulation of patients with DM and AF. Initial reports suggested that treatment with metformin, sulfonylureas or insulin in patients receiving vitamin-K antagonists led to a significant reduction in international normalized ratio values, likely due to increased CYP2C9 expression from lower blood glucose levels and improved hepatic inflammation control[71]. By contrast, sitagliptin and polyethylene glycol loxenatide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, appear to have no impact on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of warfarin[72,73]. Concerns have also been raised regarding concomitant use of NOACs with pioglitazone and repaglinide, while canagliflozine may interact with dabigatran etexilate, a P-gp substrate[74]. However, a meta-analysis by Grymonprez et al[75], which included 20889 participants with AF receiving P-gp/CYP3A4 inhibitors, demonstrated that NOACs provided comparable efficacy to vitamin-K antagonists; notably, in patients receiving amiodarone for rhythm control, the protective effect of NOACs against stroke and systemic embolism was preserved, with additional benefit in reducing intracranial bleeding, albeit at the cost of an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. In addition, as DM itself has been hypothesized to interfere with CYP450 enzymes and P-gp function, other studies sought to investigate the possibility of altering the metabolism and bioavailability of oral anticoagulants, without significant associations[76].

Finally, percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion is considered an option for high bleeding risk patients in need of thromboembolism prophylaxis[77]. In patients with DM and AF, left atrial appendage occlusion appears to be as safe and effective as in patients without DM, both periprocedurally and in a follow-up of 6-12 months[78,79]. However, in some studies, DM was associated with increased readmission rates post-left atrial appendage closure, owing to increased bleeding risk[80,81].

DM management: DM is a major comorbidity in AF management and optimal glycemic control plays a pivotal role in improving outcomes. Higher HbA1c levels have been associated with adverse events in patients with AF and DM, including increased risks of stroke, AF-related hospitalizations and mortality[82,83]. Poor glycemic control has also been linked to reduced arrhythmia-free survival after catheter ablation. In a cohort of 298 patients, tighter glycemic control during the 12 months before the procedure was associated with a significantly lower risk of AF recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), with recurrence rates more than twice as high in patients with HbA1c > 9% compared with HbA1c < 7% (68.75% vs 32.4%; P < 0.0001)[84].

Cardiovascular risk factor management: DM is frequently accompanied by cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, heart failure, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea, all of which have been shown to promote AF and worsen clinical outcomes[27,85]. In a cohort of 7169 diabetic patients, a body mass index (BMI) of 25-30 kg/m2 and > 30 kg/m2 was associated with a 1.9-fold and 2.9-fold higher risk of AF, respectively, compared with a normal BMI[86]. Moreover, DM is a key component of the metabolic syndrome, which has been linked to an increased risk of incident AF and reduced long-term arrhythmia-free survival after ablation[87,88]. Lifestyle and dietary changes, optimal blood pressure control, weight reduction and continuous positive airway pressure treatment may mitigate the risk of incident AF and delay AF progression[89-91].

Rate vs rhythm control: Patients with DM frequently present in a more advanced AF stage and face various challenges in rhythm control management. Data from the ORBIT-AF registry demonstrated that diabetic patients were more likely to have persistent or permanent AF and were predominantly managed with rate-control therapies, particularly beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, and digoxin, while being less frequently treated with rhythm-control interventions, such as cardioversion, catheter ablation or flecainide use[9]. Similarly, the EORP-AF registry highlighted significant disparities in rhythm-control strategies, showing that although pharmacological cardioversion rates were comparable between diabetic and non-diabetic patients, the former were significantly less likely to undergo electrical cardioversion (16.2% vs 24.6%, P < 0.0001) or catheter ablation (3.3% vs 8.6%, P value < 0.0001)[20].

Regarding the use of AADs, preclinical data have raised concerns about reduced efficacy in DM, as exemplified by reduced flecainide and verapamil efficacy in diabetic rats[92]. Furthermore, it has also been hypothesized that diabetic patients may theoretically face a higher risk of adverse effects, given the frequent coexistence of asymptomatic coronary artery disease, heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Additionally, the frequent occurrence of corrected QT interval prolongation in this population, particularly among those treated with insulin, may further increase proarrhythmic risk[93,94].

However, recent clinical evidence from the EAST-AFNET 4 trial demonstrated that early rhythm control is both effective and safe in patients with DM, who are often asymptomatic, thereby challenging previous anticipated risks. Notably, although 86% of diabetic patients received AADs, the incidence of adverse events was comparable to that in non-diabetic patients, supporting the feasibility of a pharmacological approach in this population[95]. In line with these findings, a sub-analysis of the ATHENA and EURIDIS/ADONIS trials showed that dronedarone reduced AF recurrence and cardiovascular hospitalizations in diabetic patients with AF, while maintaining a favorable safety profile compared to placebo[96].

Role of ablation: When an interventional rhythm control approach is considered, data remain limited regarding the optimal ablation strategy in diabetic patients. Grieco et al[97] investigated PVI alone vs PVI plus complex fractionated atrial electrogram ablation in patients with paroxysmal AF and type 1 DM, a group often characterized by more pathological atrial substrate. Their findings suggest that in those with long-standing DM, frequent AF episodes and poor glycemic control (HbA1c > 7.5%), the addition of complex fractionated atrial electrogram ablation may improve rhythm outcomes without increasing procedural risk, highlighting the potential role of substrate modification in this subpopulation[97].

However, overall success rates of catheter ablation appear to be lower in patients with DM. From a pathophysiological perspective, the adverse atrial remodeling and abnormal substrate in DM may promote the formation of low-voltage areas (LVAs). LVAs are defined as sites within the atrial myocardium with < 0.5 mV of bipolar voltage on electroanatomical mapping and have been linked with worse rhythm outcomes after catheter ablation in both paroxysmal and persistent AF[98,99]. In a cohort of 912 patients, LVA presence was higher among DM patients and poor glycemic control was related to a further increase in LVAs in a linear manner[100]. From a clinical standpoint, observational studies have reported a significantly higher risk of AF recurrence following ablation in diabetic patients, even after adjustment for confounders, with a trend toward worse outcomes in those with higher HbA1c levels[101]. Similarly, the European Observational Multicentre Study identified DM as an independent predictor of AF relapse within 12 months post-ablation, especially among patients with persistent AF. Additional factors such as elevated BMI, longer AF duration, and increased left atrial volume were also independently associated with recurrence[102]. Importantly, both studies noted that the rate of periprocedural complications was similar between diabetic and non-diabetic groups, reinforcing the procedural safety of AF ablation in this population[101,102].

Glucose-lowering medications may influence AF risk and recurrence not only through glycemic control but also via pleiotropic effects on cardiac structure, electrophysiology and systemic inflammation. A summary of the effects of various antidiabetic agents on AF is shown in Table 1.

| Drug class | Effect on AF | Pathogenetic mechanisms | Type of study | Ref. |

| Metformin | Mostly positive | Anti-inflammatory (activation of AMPK), anti-oxidant, inhibition of RAGE, improved mitochondrial function and calcium homeostasis | Non-RCTs, animal studies | [102,104-108] |

| Thiazolidinediones | Mostly positive | Anti-inflammatory (PPAR-γ and angiotensin II), anti-fibrotic | Non-RCTs, meta-analysis, RCT | [109,112,113] |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | Mostly neutral | Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, improved calcium regulation | RCTs, non-RCTs, meta-analysis | [114,116-119] |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | Positive | Weight loss, anti-inflammatory, reduced epicardial adiposity | RCTs, non-RCTs, meta-analyses | [122-127] |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Positive | Anti-inflammatory (AMPK phosphorylation), improved mitochondrial function, anti-oxidant, reduced EAT volume and thickness | RCTs, non-RCTs, meta-analyses, animal studies | [128-138] |

| Insulin | Negative | Vascular inflammation, smooth muscle proliferation, endothelial dysfunction, hypoglycemia induced-autonomic nervous system activation | Non-RCT, meta-analysis | [114,139] |

Metformin: Metformin, a first-line antidiabetic agent, has demonstrated significant cardiometabolic effects, though anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms. Its multiple cardioprotective effects are mainly mediated through activation of AMPK and include attenuation of inflammation and oxidative stress, inhibition of the RAGE pathway, preservation of mitochondrial function and ATP levels, promotion of calcium homeostasis and fatty acid oxidation, reversal of atrial structural and electrical remodeling and restoration of connexin expression and action potential stability[103,104]. Several studies have shown a beneficial effect on new-onset AF reduction from metformin combination therapy or monotherapy in comparison to other antidiabetic drugs, such as sulfonylureas, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and thiazolidinediones (TZD)[105-107]. However, a cohort of 5564 patients did not demonstrate any protective effect from metformin monotherapy on new-onset AF through a 10-year follow-up, after adjusting for age, sex and other comorbidities[108]. Metformin use could also improve arrhythmia-free survival after catheter ablation, as Deshmukh et al[109] showed a 34% lower risk of recurrent AF in their cohort of 271 patients.

TZD: TZD, such as pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, are potent oral glucose-lowering medications that have exhibited beneficial effects on cardiac arrhythmias through their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Their main mechanism of action is activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, a pleiotropic receptor frequently expressed in adipose tissue and macrophages[110]. Results from animal studies suggest that pioglitazone reduces the risk of AF by modulating electrophysiological and structural remodeling through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated pathways, including attenuation of angiotensin II-induced ion channel remodeling, suppression of pro-fibrotic signaling and normalization of atrial conduction, effects largely independent of its metabolic action[111]. According to a meta-analysis of 130854 diabetic patients, use of pioglitazone but not rosiglitazone was associated with an almost 30% AF risk reduction, both for new-onset and recurrent AF[112]. In addition, pioglitazone has been hypothesized to delay the progression of AF from persistent to permanent[113].

Novel antidiabetic pharmacotherapy: Novel antidiabetic pharmacotherapy, including SGLT2 inhibitors and incretin-based therapies, such as GLP-1 RA and DPP-4 inhibitors, has shown superior results in preventing AF in comparison with traditional antidiabetic regimens, such as metformin, TZD and sulfonylureas[114]. (1) DPP-4 inhibitors. DPP-4 inhibitors perform their hypoglycemic effect by increasing serum levels of GLP-1, a peptide known to mediate insulin and inhibit glucagon secretion. It is hypothesized from animal studies that this drug class exhibits anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant actions, which, in combination with calcium regulation, could potentially lower arrhythmogenicity[115]. Results from a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan involving 90880 patients suggested that the use of sitagliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin or vildagliptin in combination with metformin could lower the incidence of new-onset AF by 35%[116]. However, the choice of DPP-4 inhibitors should be thoroughly examined in order to reduce other major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients. Results from the SAVOR-TIMI trial indicated an increased heart failure hospitalization rate with saxagliptin use; however, this was not confirmed for sitagliptin in the TECOS trial, alogliptin in the EXAMINE trial and linagliptin in the CARMELINA trial[117-120]. None of these large randomized clinical trials was designed to investigate AF outcomes with the use of DDP-4 inhibitors. However, when compared with SGLT2 inhibitors, the latter showed significantly improved outcomes regarding AF risk reduction and improved survival outcomes[121,122]; (2) GLP-1 RAs. GLP-1 RAs have shown even more promising results than DDP-4 inhibitors in preventing AF. In a propensity-matched cohort, the use of GLP-1RAs was associated with a significant reduction in incident AF by 18%, compared to DPP-4 inhibitors[123]. Even though some earlier analyses, such as the Harmony programme, showed an increased risk of AF onset with specific GLP-1 RAs compared to other treatments, novel evidence challenges this hypothesis and argues towards a protective effect of this drug class on atrial arrhythmias[124-126]. The Harmony outcomes randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigated major cardiovascular outcomes in 4717 patients receiving either albiglutide or placebo and concluded that albiglutide was associated with a lower incidence of AF or flutter compared to placebo, with a relative risk of 0.82 (95%CI: 0.64-1.06)[127]. Similarly, a post-hoc analysis of the REWIND trial suggested that subcutaneous dulaglutide did not increase atrial arrhythmias in type 2 DM patients during a follow-up of 5.4 years[128]. Finally, given the gathering evidence of GLP-1 RAs’ effects on obesity and other metabolic outcomes, several ongoing RCTs investigate the additive role of GLP-1 RAs in diabetic, obese patients who have undergone AF catheter ablation, as a weight loss medication and means of reducing AF recurrences (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06660134, NCT06184633); and (3) SGLT2 inhibitors. More recently, attention has shifted toward SGLT2 inhibitors, which have shown remarkable effects on reducing AF risk in patients with type 2 DM. The DECLARE TIMI 58 trial demonstrated a 19% reduction in AF risk, independent of sex, race, history of heart failure, or HbA1c levels over a 4-year follow-up period[129]. In a population-based cohort of 142447 patients, analyzing data from the United Kingdom Clinical Practice Research Datalink, new-onset AF risk was reduced by 15% in men and 40% in women after starting an SGLT2 inhibitor. The pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on a cellular and molecular level have been suggested in various studies. Results from animal studies on diabetic rats showed that empagliflozin exerts cardioprotective effects against atrial structural and electrical remodeling and fibrosis in type 2 DM by enhancing AMPK phosphorylation, which restores mitochondrial biogenesis, improves respiratory function, reduces oxidative stress, and modulates mitochondrial dynamics, thereby decreasing arrhythmogenicity and AF initiation[130,131]. SGLT2 inhibitors significantly decrease EAT volume and thickness in patients with type 2 DM, according to a recent meta-analysis, with consistent effects across different imaging methods, drug types, populations, and follow-up durations. These benefits are likely through reduced inflammatory signaling, restoration of adipokine balance, and enhanced lipid mobilization within EAT[132]. Another network meta-analysis by Bao et al[133] also suggested the protective effect of this drug class on EAT thickness compared to placebo and showed superior efficacy compared to GLP-1 receptor agonists and other traditional hypoglycemic therapies. Other potential mechanisms through which SGLT2 inhibitors reduce arrhythmia risk include improved cardiac hemodynamics and fluid status, neurohormonal modulation and better blood pressure and glycemic control[134]. Regarding AF outcomes, several studies have shown the beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Dapagliflozin has been linked to a decrease in clinical AF episodes and atrial high-rate episodes in patients with AF and cardiac implantable electronic devices, mediated by reduced oxidative stress and an increase in mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity percentage[135]. Çelik et al[136] demonstrated that the addition of an SGLT2 inhibitor to a patient’s antidiabetic regimen improves interatrial conduction, as measured by the pulmonary artery tissue Doppler imaging method on transthoracic echocardiography, and reduces atrial electromechanical delay, potentially lowering AF risk. SGLT2 inhibitor use was also associated with a 23%-42% relative risk reduction in AF and atrial arrhythmia recurrence after catheter ablation, as demonstrated by two independent retrospective cohorts, along with fewer adverse outcomes, including the need for cardioversion, new antiarrhythmic therapy, repeat ablation, heart failure decompensations, hospitalizations, and death[137,138]. Large ongoing RCTs focusing on the antiarrhythmic effects of empagliflozin (EMPA-AF, ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04583813) and dapagliflozin (DAPA-AF, ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05174052; and Dapagliflozin on Outcomes of Rhythm Control Strategy in Patients with AF, ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06759909) are expected to shed more light on this complex topic.

Role of insulin: In contrast to other treatments, insulin users seem to be at a higher risk of developing new-onset AF than oral antidiabetic medication users. In a nested case-control study by Liou et al[139], the incidence of AF was 1.19 times higher in patients receiving insulin treatment compared to those not on insulin. This phenomenon may reflect both poor glycemic control in this subgroup, an established risk factor for AF, the direct effects of hyperinsulinemia, including vascular inflammation, smooth muscle proliferation and endothelial dysfunction, as well as hypoglycemia-induced autonomic nervous system activation[115,139,140].

Overall, emerging evidence indicates that among currently available glucose-lowering agents, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists show the greatest promise in preventing AF and hindering disease progression, whereas insulin may be associated with a higher risk; however, large-scale randomized trials are still needed to clarify underlying mechanisms, confirm efficacy and safety and update future guideline recommendations.

Several molecular pathways have emerged as promising targets for reducing AF susceptibility in DM, although the majority of evidence remains preclinical. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation is one such strategy, with several commonly used medications currently being investigated as potential suppressors. For example, results from small human studies suggest that anti-inflammatory agents, such as colchicine, may attenuate NLRP3 inflammasome activity in other inflammatory conditions[141,142]. Similarly, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, a drug class widely prescribed in patients with DM and AF to treat other comorbidities, have demonstrated suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in rat cardiac fibroblasts[143]. In addition, atorvastatin has exhibited beneficial effects in the reduction of NLRP3 inflammasome levels, as results from a randomized, in vitro study suggest[144].

Targeting oxidative stress represents another therapeutic option. Allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, has been shown to reverse atrial electrical remodeling by downregulating the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II/sodium-calcium exchanger signaling pathway in diabetic rats[145]. Additionally, therapies aimed at restoring calcium homeostasis, such as calpain inhibition, have demonstrated favorable effects on both electrical and structural remodeling in preclinical studies[44].

Another promising target includes the AGE-RAGE axis. Increasing levels of sRAGE, the circulating form of RAGE, can inhibit the pathway by binding to the receptor and acting as a decoy[146]. Higher baseline levels of sRAGE have been associated with a reduced risk of AF recurrence after catheter ablation in diabetic patients[147]. Moreover, commonly used cardiovascular therapies such as statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and the antidiabetic drug rosiglitazone have been linked to increased sRAGE concentrations, further highlighting the therapeutic potential of this pathway[148-150]. Although these pathways may appear clinically relevant, most evidence derives from animal models, in vitro studies, or small observational human studies. Large-scale interventional studies are required to establish the exact mechanisms, evaluate therapeutic efficacy in humans, and determine the optimal timing and dosage of each intervention.

In conclusion, AF in diabetic patients represents a multifaceted clinical challenge, with closely related pathophysiological mechanisms. Optimal glycemic control and lifestyle modifications remain the cornerstone of therapeutic interventions in patients with DM. However, recent advances in therapeutic strategies, including tailored anticoagulation, rate and rhythm control and emerging pharmacological interventions, offer promising results to improve outcomes. Particularly novel antidiabetic medications may contribute significantly in the future to the reduction in AF susceptibility among diabetic patients. Ongoing large-scale RCTs, including the EMPA-AF and DAPA-AF trials, are anticipated to provide valuable insights into AF-specific outcomes associated with glucose-lowering therapies. A comprehensive, individualized approach that takes into consideration the unique metabolic and cardiovascular profile of this high-risk population is essential for effective management and reduction of morbidity and mortality.

| 1. | NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet. 2024;404:2077-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 196.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report. May 15, 2024. [cited 3 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html. |

| 3. | Huang Q, Li Y, Yu M, Lv Z, Lu F, Xu N, Zhang Q, Shen J, Zhu J, Jiang H. Global burden and risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus from 1990 to 2021, with forecasts to 2050. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1538143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48:S207-S238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 109.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke. 2021;16:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1049] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 172.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2014;114:1453-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 657] [Cited by in RCA: 935] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ajoolabady A, Nattel S, Lip GYH, Ren J. Inflammasome Signaling in Atrial Fibrillation: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:2349-2366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramos-Mondragón R, Lozhkin A, Vendrov AE, Runge MS, Isom LL, Madamanchi NR. NADPH Oxidases and Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12:1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Shrader P, Thomas L, Gersh BJ, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Singer DE, Hylek EM, Go AS, Peterson ED, Piccini JP, Fonarow GC. Care Patterns and Outcomes in Atrial Fibrillation Patients With and Without Diabetes: ORBIT-AF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1325-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Packer M. Characterization, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Implications of Inflammation-Related Atrial Myopathy as an Important Cause of Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li W, Chen X, Xie X, Xu M, Xu L, Liu P, Luo B. Comparison of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors and Glucagon-like Peptide Receptor Agonists for Atrial Fibrillation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review With Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2022;79:281-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pallisgaard JL, Lindhardt TB, Olesen JB, Hansen ML, Carlson N, Gislason GH. Management and prognosis of atrial fibrillation in the diabetic patient. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:643-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Staszewsky L, Cortesi L, Baviera M, Tettamanti M, Marzona I, Nobili A, Fortino I, Bortolotti A, Merlino L, Disertori M, Latini R, Roncaglioni MC. Diabetes mellitus as risk factor for atrial fibrillation hospitalization: Incidence and outcomes over nine years in a region of Northern Italy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109:476-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1974] [Cited by in RCA: 2031] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Aksnes TA, Schmieder RE, Kjeldsen SE, Ghani S, Hua TA, Julius S. Impact of new-onset diabetes mellitus on development of atrial fibrillation and heart failure in high-risk hypertension (from the VALUE Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:634-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huxley RR, Alonso A, Lopez FL, Filion KB, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ, Pankow JS, Selvin E. Type 2 diabetes, glucose homeostasis and incident atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Heart. 2012;98:133-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xiong Z, Liu T, Tse G, Gong M, Gladding PA, Smaill BH, Stiles MK, Gillis AM, Zhao J. A Machine Learning Aided Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relative Risk of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. Front Physiol. 2018;9:835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fatemi O, Yuriditsky E, Tsioufis C, Tsachris D, Morgan T, Basile J, Bigger T, Cushman W, Goff D, Soliman EZ, Thomas A, Papademetriou V. Impact of intensive glycemic control on the incidence of atrial fibrillation and associated cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (from the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1217-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dublin S, Glazer NL, Smith NL, Psaty BM, Lumley T, Wiggins KL, Page RL, Heckbert SR. Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and risk of atrial fibrillation. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:853-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fumagalli S, Said SA, Laroche C, Gabbai D, Boni S, Marchionni N, Boriani G, Maggioni AP, Musialik-Lydka A, Sokal A, Petersen J, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH; EORP-AF General Pilot Registry Investigators. Management and prognosis of atrial fibrillation in diabetic patients: an EORP-AF General Pilot Registry report. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2018;4:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Du X, Ninomiya T, de Galan B, Abadir E, Chalmers J, Pillai A, Woodward M, Cooper M, Harrap S, Hamet P, Poulter N, Lip GY, Patel A; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Risks of cardiovascular events and effects of routine blood pressure lowering among patients with type 2 diabetes and atrial fibrillation: results of the ADVANCE study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1128-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kwon S, Lee SR, Choi EK, Ahn HJ, Lee SW, Jung JH, Han KD, Oh S, Lip GYH. Association Between Atrial Fibrillation and Diabetes-Related Complications: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:2240-2248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hu WS, Lin CL. Impact of atrial fibrillation on stroke, heart failure, and mortality in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35:107762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bano A, Rodondi N, Beer JH, Moschovitis G, Kobza R, Aeschbacher S, Baretella O, Muka T, Stettler C, Franco OH, Conte G, Sticherling C, Zuern CS, Conen D, Kühne M, Osswald S, Roten L, Reichlin T; of the Swiss‐Investigators. Association of Diabetes With Atrial Fibrillation Phenotype and Cardiac and Neurological Comorbidities: Insights From the Swiss-AF Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gumprecht J, Lip GYH, Sokal A, Średniawa B, Mitręga K, Stokwiszewski J, Wierucki Ł, Rajca A, Rutkowski M, Zdrojewski T, Grodzicki T, Kaźmierczak J, Opolski G, Kalarus Z. Relationship between diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation prevalence in the Polish population: a report from the Non-invasive Monitoring for Early Detection of Atrial Fibrillation (NOMED-AF) prospective cross-sectional observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alijla F, Buttia C, Reichlin T, Razvi S, Minder B, Wilhelm M, Muka T, Franco OH, Bano A. Association of diabetes with atrial fibrillation types: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Marx N, Federici M, Schütt K, Müller-Wieland D, Ajjan RA, Antunes MJ, Christodorescu RM, Crawford C, Di Angelantonio E, Eliasson B, Espinola-Klein C, Fauchier L, Halle M, Herrington WG, Kautzky-Willer A, Lambrinou E, Lesiak M, Lettino M, McGuire DK, Mullens W, Rocca B, Sattar N; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:4043-4140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 999] [Cited by in RCA: 884] [Article Influence: 294.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Giraldo-Gonzalez GC, Roman-Gonzalez A, Cañas F, Garcia A. Molecular Mechanisms of Type 2 Diabetes-Related Heart Disease and Therapeutic Insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:4548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ren W, Huang Y, Meng S, Cao Z, Qin N, Zhao J, Huang T, Guo X, Chen X, Zhou Z, Zhu Y, Yu L, Wang H. Salidroside treatment decreases the susceptibility of atrial fibrillation in diabetic mice by reducing mTOR-STAT3-MCP-1 signaling and atrial inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:113196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhou X, Liu H, Feng F, Kang GJ, Liu M, Guo Y, Dudley SC Jr. Macrophage IL-1β mediates atrial fibrillation risk in diabetic mice. JCI Insight. 2024;9:e171102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu X, Liu Y, Tu D, Liu X, Niu S, Suo Y, Liu T, Li G, Liu C. Role of NLRP3-Inflammasome/Caspase-1/Galectin-3 Pathway on Atrial Remodeling in Diabetic Rabbits. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2020;13:731-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meng S, Chen X, Zhao J, Huang X, Huang Y, Huang T, Zhou Z, Ren W, Hong T, Duan J, Yu L, Wang H. Reduced FNDC5-AMPK signaling in diabetic atrium increases the susceptibility of atrial fibrillation by impairing mitochondrial dynamics and activating NLRP3 inflammasome. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024;229:116476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shi T, Wang G, Peng J, Chen M. Loss of MD1 Promotes Inflammatory and Apoptotic Atrial Remodelling in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy by Activating the TLR4/NF-κB Signalling Pathway. Pharmacology. 2023;108:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wei ZX, Cai XX, Fei YD, Wang Q, Hu XL, Li C, Hou JW, Yang YL, Chen TZ, Xu XL, Wang YP, Li YG. Zbtb16 increases susceptibility of atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetic mice via Txnip-Trx2 signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kantharia BK, Tabary M, Wu L, Wang X, Narasimhan B, Linz D, Heijman J, Wehrens XHT. Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation: Insight From Basic to Translational Science Into the Mechanisms and Management. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2025;36:2755-2766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhou L, Liu Y, Wang Z, Liu D, Xie B, Zhang Y, Yuan M, Tse G, Li G, Xu G, Liu T. Activation of NADPH oxidase mediates mitochondrial oxidative stress and atrial remodeling in diabetic rabbits. Life Sci. 2021;272:119240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yang Y, Zhao J, Qiu J, Li J, Liang X, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Fu H, Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Tse G, Li G, Liu T. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor Allopurinol Prevents Oxidative Stress-Mediated Atrial Remodeling in Alloxan-Induced Diabetes Mellitus Rabbits. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Qiu J, Zhao J, Li J, Liang X, Yang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Fu H, Korantzopoulos P, Liu T, Li G. NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin prevents atrial remodeling in alloxan-induced diabetic rabbits. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Qian LL, Liu XY, Li XY, Yang F, Wang RX. Effects of Electrical Remodeling on Atrial Fibrillation in Diabetes Mellitus. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2023;24:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bohne LJ, Jansen HJ, Daniel I, Dorey TW, Moghtadaei M, Belke DD, Ezeani M, Rose RA. Electrical and structural remodeling contribute to atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:118-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Polina I, Jansen HJ, Li T, Moghtadaei M, Bohne LJ, Liu Y, Krishnaswamy P, Egom EE, Belke DD, Rafferty SA, Ezeani M, Gillis AM, Rose RA. Loss of insulin signaling may contribute to atrial fibrillation and atrial electrical remodeling in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:7990-8000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Heijman J, Voigt N, Nattel S, Dobrev D. Calcium handling and atrial fibrillation. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2012;162:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bukowska A, Lendeckel U, Bode-Böger SM, Goette A. Physiologic and pathophysiologic role of calpain: implications for the occurrence of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:e115-e127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wang Q, Yuan J, Shen H, Zhu Q, Chen B, Wang J, Zhu W, Yorek MA, Hall DD, Wang Z, Song LS. Calpain inhibition protects against atrial fibrillation by mitigating diabetes-associated atrial fibrosis and calcium handling dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mice. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21:1143-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Williams S, Raheim SA, Khan MI, Rubab U, Kanagala P, Zhao SS, Marshall A, Brown E, Alam U. Cardiac Autonomic Neuropathy in Type 1 and 2 Diabetes: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Management. Clin Ther. 2022;44:1394-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Chen PS, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Nattel S. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2014;114:1500-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rizzo MR, Sasso FC, Marfella R, Siniscalchi M, Paolisso P, Carbonara O, Capoluongo MC, Lascar N, Pace C, Sardu C, Passavanti B, Barbieri M, Mauro C, Paolisso G. Autonomic dysfunction is associated with brief episodes of atrial fibrillation in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lin M, Ai J, Harden SW, Huang C, Li L, Wurster RD, Cheng ZJ. Impairment of baroreflex control of heart rate and structural changes of cardiac ganglia in conscious streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice. Auton Neurosci. 2010;155:39-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bassil G, Chang M, Pauza A, Diaz Vera J, Tsalatsanis A, Lindsey BG, Noujaim SF. Pulmonary Vein Ganglia Are Remodeled in the Diabetic Heart. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Mengstie MA, Chekol Abebe E, Behaile Teklemariam A, Tilahun Mulu A, Agidew MM, Teshome Azezew M, Zewde EA, Agegnehu Teshome A. Endogenous advanced glycation end products in the pathogenesis of chronic diabetic complications. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:1002710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Liu Y, Liang C, Liu X, Liao B, Pan X, Ren Y, Fan M, Li M, He Z, Wu J, Wu Z. AGEs increased migration and inflammatory responses of adventitial fibroblasts via RAGE, MAPK and NF-kappaB pathways. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Raposeiras-Roubín S, Rodiño-Janeiro BK, Grigorian-Shamagian L, Seoane-Blanco A, Moure-González M, Varela-Román A, Álvarez E, González-Juanatey JR. Evidence for a role of advanced glycation end products in atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:397-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Al Rifai M, Schneider AL, Alonso A, Maruthur N, Parrinello CM, Astor BC, Hoogeveen RC, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, Ballantyne CM, Halushka MK, Selvin E. sRAGE, inflammation, and risk of atrial fibrillation: results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:180-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zheng DL, Wu QR, Zeng P, Li SM, Cai YJ, Chen SZ, Luo XS, Kuang SJ, Rao F, Lai YY, Zhou MY, Wu FL, Yang H, Deng CY. Advanced glycation end products induce senescence of atrial myocytes and increase susceptibility of atrial fibrillation in diabetic mice. Aging Cell. 2022;21:e13734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Yang F, Liu HH, Zhang L, Zhang XL, Zhang J, Li F, Zhao N, Zhang ZY, Kong Q, Liu XY, Wu Y, Yu ZM, Qian LL, Wang RX. Advanced Glycation End Products Downregulate Connexin 43 and Connexin 40 in Diabetic Atrial Myocytes via the AMPK Pathway. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:3045-3056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Luo Y, Ma W, Kang Q, Pan H, Shi L, Ma J, Song J, Gong D, Kang K, Jin X. Atrial APD prolongation caused by the upregulation of RAGE and subsequent I (NaL) increase in diabetic patients. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2025;57:1115-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zou R, Zhang M, Lv W, Ren J, Fan X. Role of epicardial adipose tissue in cardiac remodeling. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024;217:111878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ernault AC, Verkerk AO, Bayer JD, Aras K, Montañés-Agudo P, Mohan RA, Veldkamp M, Rivaud MR, de Winter R, Kawasaki M, van Amersfoorth SCM, Meulendijks ER, Driessen AHG, Efimov IR, de Groot JR, Coronel R. Secretome of atrial epicardial adipose tissue facilitates reentrant arrhythmias by myocardial remodeling. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:1461-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Couselo-Seijas M, Vázquez-Abuín X, Gómez-Lázaro M, Pereira L, Gómez AM, Caballero R, Delpón E, Bravo S, González-Juanatey JR, Eiras S. FABP4 Enhances Lipidic and Fibrotic Cardiac Structural and Ca(2+) Dynamic Changes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2024;17:e012683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gaeta M, Bandera F, Tassinari F, Capasso L, Cargnelutti M, Pelissero G, Malavazos AE, Ricci C. Is epicardial fat depot associated with atrial fibrillation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2017;19:747-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | van Rosendael AR, Dimitriu-Leen AC, van Rosendael PJ, Leung M, Smit JM, Saraste A, Knuuti J, van der Geest RJ, van der Arend BW, van Zwet EW, Scholte AJ, Delgado V, Bax JJ. Association Between Posterior Left Atrial Adipose Tissue Mass and Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10:e004614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Li TL, Zhu NN, Yin Z, Sun J, Guo JP, Yuan HT, Shi XM, Guo HY, Li SX, Shan ZL. Transcriptomic analysis of epicardial adipose tissue reveals the potential crosstalk genes and immune relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation. Gene. 2024;920:148528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, Crijns HJGM, De Potter TJR, Dwight J, Guasti L, Hanke T, Jaarsma T, Lettino M, Løchen ML, Lumbers RT, Maesen B, Mølgaard I, Rosano GMC, Sanders P, Schnabel RB, Suwalski P, Svennberg E, Tamargo J, Tica O, Traykov V, Tzeis S, Kotecha D; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3314-3414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 1369] [Article Influence: 684.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864-2870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3642] [Cited by in RCA: 3657] [Article Influence: 146.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Fangel MV, Nielsen PB, Larsen TB, Christensen B, Overvad TF, Lip GYH, Goldhaber SZ, Jensen MB. Type 1 versus type 2 diabetes and thromboembolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Bansilal S, Bloomgarden Z, Halperin JL, Hellkamp AS, Lokhnygina Y, Patel MR, Becker RC, Breithardt G, Hacke W, Hankey GJ, Nessel CC, Singer DE, Berkowitz SD, Piccini JP, Mahaffey KW, Fox KA; ROCKET AF Steering Committee and Investigators. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in patients with diabetes and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the Rivaroxaban Once-daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF Trial). Am Heart J. 2015;170:675-682.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ezekowitz JA, Lewis BS, Lopes RD, Wojdyla DM, McMurray JJ, Hanna M, Atar D, Cecilia Bahit M, Keltai M, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Ruzyllo W, Wallentin L, Granger CB, Alexander JH. Clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes and atrial fibrillation treated with apixaban: results from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2015;1:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Patti G, Di Gioia G, Cavallari I, Nenna A. Safety and efficacy of nonvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in diabetic patients with atrial fibrillation: A study-level meta-analysis of phase III randomized trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Baker WL, Beyer-Westendorf J, Bunz TJ, Eriksson D, Meinecke AK, Sood NA, Coleman CI. Effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban and warfarin for prevention of major adverse cardiovascular or limb events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2107-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hernandez AV, Bradley G, Khan M, Fratoni A, Gasparini A, Roman YM, Bunz TJ, Eriksson D, Meinecke AK, Coleman CI. Rivaroxaban vs. warfarin and renal outcomes in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with diabetes. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Stage TB, Pottegård A, Henriksen DP, Christensen MM, Højlund K, Brøsen K, Damkier P. Initiation of glucose-lowering treatment decreases international normalized ratio levels among users of vitamin K antagonists: a self-controlled register study. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Wright DH, Herman GA, Maes A, Liu Q, Johnson-Levonas AO, Wagner JA. Multiple doses of sitagliptin, a selective DPP-4 inhibitor, do not meaningfully alter pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:1157-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 73. | Zhou H, Wu G, Lv D, Lin M, Shentu J. Warfarin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are not affected by concomitant administration of the long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist polyethylene glycol loxenatide. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2025;63:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Pomero F, Dentali F, Mumoli N, Salomone P, Tangianu F, Desideri G, Mastroiacovo D. The continuous challenge of antithrombotic strategies in diabetes: focus on direct oral anticoagulants. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:1247-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Grymonprez M, Vanspranghe K, Steurbaut S, De Backer TL, Lahousse L. Non-vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) Versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Using P-gp and/or CYP450-Interacting Drugs: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2023;37:781-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Samoš M, Bolek T, Stančiaková L, Škorňová I, Ivanková J, Kovář F, Galajda P, Kubisz P, Staško J, Mokáň M. Does type 2 diabetes affect the on-treatment levels of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;135:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Glikson M, Wolff R, Hindricks G, Mandrola J, Camm AJ, Lip GYH, Fauchier L, Betts TR, Lewalter T, Saw J, Tzikas A, Sternik L, Nietlispach F, Berti S, Sievert H, Bertog S, Meier B. EHRA/EAPCI expert consensus statement on catheter-based left atrial appendage occlusion - an update. EuroIntervention. 2020;15:1133-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Litwinowicz R, Bartus M, Ceranowicz P, Brzezinski M, Kapelak B, Lakkireddy D, Bartus K. Left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in diabetes mellitus patients with atrial fibrillation: Long-term results. J Diabetes. 2019;11:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Azizy O, Rammos C, Lehmann N, Rassaf T, Kälsch H. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2017;14:407-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Murthi M, Vardar U, Sana MK, Shaka H. Causes and predictors of immediate and short-term readmissions following percutaneous left atrial appendage closure procedure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022;33:2213-2216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Morita S, Malik AH, Kuno T, Ando T, Kaul R, Yandrapalli S, Briasoulis A. Analysis of outcome of 6-month readmissions after percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion. Heart. 2022;108:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Papazoglou AS, Kartas A, Moysidis DV, Tsagkaris C, Papadakos SP, Bekiaridou A, Samaras A, Karagiannidis E, Papadakis M, Giannakoulas G. Glycemic control and atrial fibrillation: an intricate relationship, yet under investigation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Kanellopoulou K, Matsoukis I, Athanasopoulou T, Ganotopoulou A, Zimpounoumi N, Triantafillopoulou C, Klonos D, Skorda L, Sianni A. The role of HbA1c on mortality in patients with medical history of ischemic stroke and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Atherosclerosis. 2018;275:e203. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Donnellan E, Aagaard P, Kanj M, Jaber W, Elshazly M, Hoosien M, Baranowski B, Hussein A, Saliba W, Wazni O. Association Between Pre-Ablation Glycemic Control and Outcomes Among Patients With Diabetes Undergoing Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2019;5:897-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Joseph JJ, Deedwania P, Acharya T, Aguilar D, Bhatt DL, Chyun DA, Di Palo KE, Golden SH, Sperling LS; American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Hypertension. Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145:e722-e759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 102.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Grundvold I, Bodegard J, Nilsson PM, Svennblad B, Johansson G, Östgren CJ, Sundström J. Body weight and risk of atrial fibrillation in 7,169 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes; an observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Xia Y, Li XF, Liu J, Yu M, Fang PH, Zhang S. The influence of metabolic syndrome on atrial fibrillation recurrence: five-year outcomes after a single cryoballoon ablation procedure. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2021;18:1019-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Zheng Y, Xie Z, Li J, Chen C, Cai W, Dong Y, Xue R, Liu C. Meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome and its individual components with risk of atrial fibrillation in different populations. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Yang L, Chung MK. Lifestyle changes in atrial fibrillation management and intervention. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:2163-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Santoro F, Di Biase L, Trivedi C, Burkhardt JD, Paoletti Perini A, Sanchez J, Horton R, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, Bai R, Santangeli P, Lakkireddy D, Reddy M, Elayi CS, Hongo R, Beheiry S, Hao S, Schweikert RA, Viles-Gonzalez J, Fassini G, Casella M, Dello Russo A, Tondo C, Natale A. Impact of Uncontrolled Hypertension on Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Outcome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:164-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Holmqvist F, Guan N, Zhu Z, Kowey PR, Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Hylek EM, Mahaffey KW, Freeman JV, Chang P, Holmes DN, Peterson ED, Piccini JP, Gersh BJ; ORBIT-AF Investigators. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy on outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation-Results from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF). Am Heart J. 2015;169:647-654.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ito I, Hayashi Y, Kawai Y, Iwasaki M, Takada K, Kamibayashi T, Yamatodani A, Mashimo T. Diabetes mellitus reduces the antiarrhythmic effect of ion channel blockers. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Aburisheh K, AlKheraiji MF, Alwalan SI, Isnani AC, Rafiullah M, Mujammami M, Alfadda AA. Prevalence of QT prolongation and its risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2023;23:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Gastaldelli A, Emdin M, Conforti F, Camastra S, Ferrannini E. Insulin prolongs the QTc interval in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R2022-R2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Metzner A, Willems S, Borof K, Breithardt G, Camm AJ, Crijns HJGM, Eckardt L, Fabritz L, Gessler N, Goette A, Reissmann B, Schnabel RB, Schotten U, Zapf A, Rillig A, Kirchhof P. Diabetes and Obesity and Treatment Effect of Early Rhythm Control vs Usual Care in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Secondary Analysis of the EAST-AFNET 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10:932-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Handelsman Y, Bunch TJ, Rodbard HW, Steinberg BA, Thind M, Bigot G, Konigsberg L, Wieloch M, Kowey PR. Impact of dronedarone on patients with atrial fibrillation and diabetes: A sub-analysis of the ATHENA and EURIDIS/ADONIS studies. J Diabetes Complications. 2022;36:108227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Grieco D, Palamà Z, Borrelli A, De Ruvo E, Sciarra L, Scarà A, Goanta E, Calabrese V, Pozzilli P, Di Sciascio G, Calò L. Diabetes mellitus and atrial remodelling in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Role of electroanatomical mapping and catheter ablation. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2018;15:185-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |