Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.111468

Revised: July 21, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 9.3 Hours

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary and peripheral stenoses has advanced rapidly over the past three decades, driven by a series of innovative techniques since the introduction of the first balloon angioplasty. Significant progress in stent technology, beginning with bare-metal stents and followed by drug-eluting stents, has expanded the scope for successful revascularisation in complex lesions. However, challenges such as late stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis (ISR) persist. Thus, further improvement in PCI techniques and devices is essential to achieve better patient outcomes. In recent years, drug-coated ball

Core Tip: Percutaneous coronary intervention has advanced rapidly over the past four decades. Despite significant progress in stent technology, there is still risk of late stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis in long-term. Further improvement in percutaneous coronary intervention techniques/devices is imperative to achieve better outcomes. In recent years, drug-coated balloons have emerged as a viable alternative designed to overcome the limitations associated with drug-eluting stents. Drug-coated balloon leaves no residual metal inside coronary arteries and consequently suitable for an abridged antiplatelet regimen. They have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of in-stent restenosis and can be useful in as small-vessel disease and diffuse lesions.

- Citation: Bhandari M, Pradhan A, Behera S, Singh AK. Coronary drug-coated balloons: Current evidence and emerging trends. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 111468

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/111468.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.111468

The incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) has increased markedly over the years, with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) becoming the primary therapeutic approach, particularly for patients with acute coronary syndrome and symptomatic stable CAD. The field of interventional cardiology has evolved significantly since the first percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty was performed 40 years ago[1]. This evolution began with the invention of a balloon catheter mounted on a fixed wire to dilate coronary stenoses. It subsequently progressed through bare-metal stents (BMSs), first-generation drug-eluting stents (DESs), and second- and third-generation biodegradable polymer-based DESs, culminating in the development of bioabsorbable stents, which are still under refinement. Each technological advance improved outcomes but introduced new challenges. Plain balloon angioplasty was associated with early vessel re-occlusion. This was mitigated by BMSs, although they brought the risk of in-stent restenosis (ISR). DESs helped reduce ISR but were associated with stent thrombosis due to metallic scaffolds, polymer coatings, and the non-selective cytostatic and cytotoxic agents used. Despite substantial progress in stent technology, optimizing the balance between decreased target lesion revascularisation, stent thrombosis, and bleeding remains a clinical challenge. Bioabsorbable stents were developed to eliminate permanent metallic implants; however, they were linked to a high incidence of stent thrombosis due to their thick struts and are currently suitable only for simple lesions. Further technological advancement is needed to overcome these limitations[2]. The most recent innovation is the drug-coated balloon (DCB), which can treat a variety of coronary lesions while avoiding permanent metallic implantation. This review outlines the development, applications, and clinical efficacy of DCBs in coronary intervention.

The first percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) was performed in September 1977 by Andreas Grüntzig, a Swiss radiologist, in Zurich[3]. It was a plain balloon angioplasty (POBA) successfully conducted on a left coronary artery lesion in a 38-year-old patient, Adolph Bachman. PTCA opens the artery primarily through plaque compression; however, the main alteration in lumen geometry is caused by fracturing and fissuring of the atheroma, which extends into the vessel wall to varying depths and lengths. This vessel injury led to two major limitations of PTCA: Acute vessel closure and restenosis[3]. To address these limitations, stents were introduced. Jacques Puel was the first to perform angioplasty using a BMS in March 1986 in France. PCI with BMS implantation (Palmaz-Schatz model, stainless steel platform) demonstrated superiority over POBA in two major clinical trials[4,5]. Although BMS reduced the incidence of acute vessel closure by preventing arterial recoil and stabilizing arterial dissection compared with balloon angioplasty, ISR still developed in 20%-30% of lesions. This was attributed to exuberant neointimal proliferation over denuded endothelium, driven by inflammation[6].

The first DES to receive the CE mark in 2002 and the United States Food and Drug Administration approval in 2003 was the Cypher stent (Cordis, Santa Clara, CA, United States), which consisted of a sirolimus-eluting formulation on a stainless steel platform with a strut thickness of 132 µm. DESs were developed to address the problem of ISR associated with BMSs, and they demonstrated clear superiority over BMSs in reducing both ISR and target lesion revascularisation (TLR) in major randomised controlled trials (RCTs)[7,8]. The Taxus DES (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, United States), a paclitaxel-eluting stent with a stainless steel platform and strut thickness of 140 µm, received United States Food and Drug Administration approval in 2004. It also outperformed BMSs for de novo lesions in the Taxus I trial with respect to ISR and TLR[9,10]. These two first-generation DESs were broadly comparable in terms of reducing ISR.

Subsequently, refinements were made to stent design and polymer coatings, with the introduction of biocompatible agents such as everolimus and zotarolimus, to enhance flexibility and deliverability. However, first-generation stents were associated with a higher incidence of late and very late stent thrombosis due to their relatively thick struts[11]. Second-generation stents, constructed from cobalt-chromium or platinum-chromium alloys, were more durable and fracture-resistant, enabling thinner struts. This led to improved angiographic and clinical outcomes and permitted a shorter duration of antiplatelet therapy[12,13]. Nevertheless, despite the reduction in ISR, late stent loss and thrombosis remained concerns, often attributed to hypersensitivity to the polymer. In response, newer designs featuring bio

Although the evidence-based use of newer-generation DESs has led to excellent clinical outcomes, their widespread use has resulted in increasing amounts of permanent metal being implanted in the coronary arteries. Moreover, the mandatory requirement for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) following DES implantation may be prohibitive for certain patient cohorts. Importantly, some clinical scenarios may not be suitable for the use of metallic stents at all.

Bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds (BVSs) were developed as the fourth major advancement in interventional cardiology. The underlying concept was that stent scaffolds are required only temporarily after implantation to prevent acute recoil and maintain vessel integrity. Once the initial support is no longer needed, degradation of the scaffold would allow restoration of vasomotor and endothelial function, thereby reducing neoatherosclerosis and promoting favourable vascular remodelling. Additionally, the absence of permanent metallic components reduces the risk of stent thrombosis, permits a shorter duration of DAPT, and preserves the option for coronary artery bypass grafting if required[14,15].

Although the concept of BVS generated considerable global enthusiasm, its clinical application encountered several challenges, ultimately leading to market withdrawal. The ABSORB III trial reported higher rates of target lesion failure compared with newer-generation DESs, primarily due to an increased incidence of target lesion-related myocardial infarction and elevated rates of stent thrombosis[16,17]. Contributing factors included suboptimal lesion preparation, inappropriate lesion selection (particularly in vessels with a reference diameter ≥ 2.50 mm), thick strut profiles, and the use of poly-L-lactide, a scaffold material shown in porcine models to promote thrombogenicity, inflammatory cell adhesion, and delayed endothelialisation. Despite these setbacks, BVS development programmes continue, with ongoing efforts aimed at addressing these limitations and improving device performance.

The DCB is a novel device used in PTCA. Its core principle is the rapid healing of the vessel wall enabled by the swift release of an antiproliferative drug. DCBs are thought to yield satisfactory outcomes in selected coronary lesions. Although dissection leading to acute vessel closure was a primary concern with POBA, a study by Nishida et al[18] in 2002 demonstrated that non-flow-limiting dissections identified on intravascular ultrasound achieved better outcomes than BMS. These findings suggest that POBA is not entirely unfavourable, thus supporting the rationale for using DCBs in coronary interventions.

Although the use of DESs reduces the risk of ISR, there remains a risk of late and very late stent thrombosis. Consequently, patients are typically prescribed prolonged DAPT for up to 12 months to allow complete endothelialisation of the stent. While advances in stent platforms and the adoption of biocompatible or biodegradable polymers have made shorter DAPT durations feasible in select cases, a minimum of 6 months of therapy is still generally preferred. However, DAPT is associated with an increased risk of haemorrhagic complications, which can contribute to higher mortality, particularly among older patients, individuals with a history of bleeding, or those with bleeding diatheses. Patients on long-term anticoagulation are also at increased risk of major bleeding when DAPT is added. Furthermore, for patients requiring major surgery, withholding DAPT poses a significant risk of stent thrombosis and its potentially severe consequences[19].

Another limitation of DESs is the permanent presence of metallic components and, in many cases, durable polymers within the artery. Both elements can provoke vascular inflammation, contribute to neoatherosclerosis, and increase the risk of restenosis or very late stent thrombosis[20]. Metallic stents may also impair physiological vasomotor function and inhibit late luminal enlargement. When implanted in distal coronary segments, they may preclude future bypass grafting at that site. As vessel size is a strong predictor of restenosis, stent implantation in small vessels carries an elevated risk of ISR and should be avoided whenever possible[21]. Despite technological improvements, coronary bifurcation lesions continue to present challenges in PCI due to suboptimal clinical outcomes, especially in the side branch (SB). While DESs have significantly reduced ISR rates in the main branch (MB) (from as high as 40%-60% to approximately 2.5%), restenosis at the SB ostium remains problematic and often necessitates repeat revascularisation. Stent thrombosis occurs in up to 4.4% of patients following PCI for bifurcation lesions compared with approximately 1.4% in those with non-bifurcation lesions. The risk of subacute stent thrombosis is particularly elevated with two-stent techniques, as demonstrated in multiple trials[21]. Similarly, diffuse coronary lesions remain challenging because the use of longer stents increases the likelihood of stent thrombosis.

The DCB is an innovative treatment strategy for CAD based on the rapid, homogeneous transfer of antiproliferative drugs into the vessel wall through a single balloon inflation. The fundamental principle of DCB therapy is the accelerated healing of the vessel wall achieved via rapid drug release. As the drug is delivered in full to the smooth muscle cells over a short duration, a sustained antiproliferative effect is maintained during the critical early hours to days following angioplasty. A DCB is a semi-compliant angioplasty balloon coated with an antiproliferative agent. Unlike the prolonged drug release associated with DESs, a DCB releases its drug payload transiently, typically within 30-60 seconds[22]. While DESs were originally introduced to reduce ISR through controlled, sustained drug release, the late development of neoatherosclerosis and stent thrombosis remains a concern, even with second-generation devices. Consequently, DCBs have become an appealing alternative, aligning with the concept of “leaving nothing behind” and avoiding the elevated thrombotic risk associated with even temporary implants such as BVS[23].

Initial experimental studies have shown that rapid drug uptake by the vessel wall, along with drug persistence to compensate for the short contact time, is a key requirement for non-stent-based local drug delivery approaches. A variety of coatings were tested on balloon catheters, but attention eventually focused on taxane compounds, including protaxel and paclitaxel. Later, a combination of a highly lipophilic drug and a specific coating matrix was evaluated in a small first-in-human trial for coronary ISR, which demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of restenosis[24]. One important feature of local paclitaxel therapy is the phenomenon of positive remodelling, which results in late luminal enlargement following DCB treatment.

More recently, sirolimus and its derivatives have also been explored for use in DCBs. However, ‘limus’ compounds face limitations, including lower tissue transfer rates compared with paclitaxel and reversible binding to the rapamycin receptor. Several strategies have been developed to address these challenges in sirolimus drug delivery systems[23,25]. One such approach involves a liquid formulation delivered via a porous balloon. The SABRE (signal amplification by reversible exchange) trial was the first clinical study to evaluate this method for coronary ISR[26]. Another approach uses a crystalline sirolimus coating with butylated hydroxytoluene as an excipient, resulting in vessel concentrations of up to 50% of the initial dose at 1 month. A randomised clinical trial using this formulation in DES ISR found comparable in-segment late lumen loss (LLL) after 6 months between paclitaxel- and sirolimus-coated balloon groups. Additionally, no difference in clinical outcomes was observed between the groups up to 12 months of follow-up[25,27].

Several types of DCBs are commercially available for coronary use. Paclitaxel remains the drug of choice, typically used at a dose ranging between 2 mg/mm2 and 3.5 mg/mm2 on the balloon surface. This preference is largely due to the critical interplay among drug dose, formulation, release kinetics, and lesion characteristics, all of which affect the vascular response to DCB therapy. However, as no clear “class effect” has been observed across different platforms, current guidelines recommend the use of both paclitaxel- and sirolimus-based DCBs[28].

To maximise the therapeutic benefit of a DCB, proper lesion preparation is essential. For uncomplicated lesions, pre-dilatation using a semi-compliant or non-compliant balloon with a 1:1 balloon-to-artery ratio is usually sufficient. In cases where balloon advancement is difficult or the vessel is underfilled or undersized, serial dilatation should be initiated with a smaller balloon, followed by reassessment after administering vasodilators. If the lesion does not yield to a standard semi-compliant or non-compliant balloon, high-pressure non-compliant balloons or specialised devices such as scoring or cutting balloons should be employed, particularly in patients with ISR. In selected cases, adjunctive therapies such as rotational atherectomy, orbital atherectomy, laser atherectomy, or intravascular lithotripsy may be used to facilitate adequate lesion preparation. An optimally prepared lesion is confirmed by: (1) Complete inflation of the correctly sized balloon; (2) Residual stenosis ≤ 30%; and (3) Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3 and 4. Absence of flow-limiting dissection (types A and B are acceptable). For successful DCB delivery, a well-engaged guide catheter with sufficient support is critical to ensure the device reaches the target lesion on the first attempt. The DCB should be appropriately sized and inflated for a prolonged duration. Extreme care must be taken during handling because some DCB brands may shed the drug coating upon contact with liquid. The key procedural tips for DCB implantation are listed in Table 1[24].

| Guide catheter support: Proper guide catheter support or use of guide catheter extension to ensure DCB delivery in one attempt |

| Optimal lesion preparation: Non-compliant/scoring balloon/debulking with rota-ablation if needed |

| Device delivery: Quick and smooth delivery of DCB to the target site |

| Deployment: Prolonged inflation of a fully inflated balloon of the correct size |

| End results: < 30% residual stenosis; TIMI flow > 3; absence of flow limiting dissections |

The interventional treatment of coronary small-vessel disease, defined as lesions in vessels ≤ 2.5 mm in diameter, accounts for approximately 30%-50% of all coronary procedures. The clinical feasibility of DCBs was initially evaluated in several non-randomised trials, followed by RCTs. The peptide coassembly design (PEPCAD) I study was the first RCT to assess the performance of a DCB (SeQuent Please) in small vessels. This study included 114 patients with lesions < 2.8 mm in diameter[29]. At 6 months, in-segment LLL with a BMS was 0.62 ± 0.73 mm, whereas in patients treated with DCB alone, LLL was significantly lower at 0.16 ± 0.38 mm. At 12 months, the rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was 6.1% in the DCB group compared with 37.5% in the BMS group, mainly due to differences in TLR. Excellent clinical outcomes were maintained at 36 months of follow-up in the DCB-only group[30]. The BELLO trial was the first RCT involving 182 patients with lesions < 2.8 mm, randomised to receive either an InPact Falcon balloon or the Taxus (paclitaxel eluting) DES. After 6 months, LLL was significantly lower in the DCB arm than in the DES arm (0.08 ± 0.38 mm vs 0.29 ± 0.44 mm; P = 0.001), translating into a reduction in MACEs at 3 years of follow-up[31,32]. Similarly, the SeQuent SVD Registry, which enrolled 479 patients with de novo lesions in small reference vessels ( ≥ 2.0 mm, ≤ 2.75 mm), reported lower TLR and MACE rates at 9 months with DCB (4.7% and 3.6%, respectively), suggesting that DCB is a suitable alternative to DES in small-vessel disease[33]. In the drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease trial, DCB was also shown to be non-inferior to DES for the treatment of native small coronary vessel disease, with comparable event rates at 12 months[34]. The various other trials of DCBs in small coronary vessels are described in Table 2.

| Trial | Setting | Numbers of patients | Design | Primary end points | Secondary endpoints | |||

| PACCOCATH ISR, Scheller et al[24], 2006 | ISR | 52 | DCB vs POBA in BMS ISR | LLL: 0.003 ± 0.48 mm vs 0.74 ± 0.86 mm in 6 months | Binary stenosis: 5% vs 43% in 6 months | TLR: 0% vs 23% | ST: 0% vs 0% | |

| PEPCAD II ISR, Unverdorben et al[36], 2009 | ISR | 131 | DCB vs PES in BMS ISR | LLL: 0.17 ± 0.42 mm vs 0.38 ± 0.61 mm in 6 months | Binary stenosis: 7% vs 20% in 36 months | TLR: 6.3% vs 15.4% in 36 months | ST: 0% vs 0% | |

| PATENE-C, Scheller et al[49], 2016 | ISR | 61 | PCSB vs USB in BMS ISR | LLL: 0.17 ± 0.40 mm vs 0.48 ± 0.51 mm in 6 months | Binary stenosis: 7% vs 41% in 12 months | TLR: 3% vs 32% in 36 months | ST: 0% vs 0% | |

| PEPCAD DES, Rittger et al[50], 2012; Rittger et al[51], 2012 | ISR | 110 | DCB vs POBA | LLL: 0.43 ± 0.61 mm vs 1.03 ± 0.77 mm in 6 months | Binary stenosis: 17.2% vs 58.1% in 36 months | TLR: 19.4% vs 36.8% in 36 months | ST: 1% vs 4% | |

| ISAR DESIRE-3, Byrne et al[37], 2013; Giacoppo et al[38], 2013 | ISR | 402 | DCB vs PES vs POBA | DS %: 38% in DCB vs 37.4% in PES vs 54.1% in POBA in 6-8 months | NA | TLR: 22.1% in DCB vs 13.5% in PES; 43.5% in POBA vs 33.3% in DCB; 24.2% in PES vs 50.8% POBA | ST: 1% vs 1% vs 0% (12 months); 1% vs 2% vs 0% (36 months) | |

| ISAR DESIRE 4, Kufner et al[52], 2017 | ISR | 252 | DCB vs SB-DCB | DS %: 40.4 ± 21.4% vs 35 ± 16.8 in 6-8 months | Binary stenosis: 32.0% vs 18.5% | TLR: 21.8% vs 16.2% in 12 months | ST: 0% vs 0% in 12 months | |

| PICCOLETO, Cortese et al[53], 2010 | Small vessel disease | 57 | PCB vs DES in small vessel disease | DS %: 43.6% vs 24.3% | MACE: 35.7% vs 13.8% in 6-9 months | |||

| SeQuent SVD registry, Cortese et al[54], 2012 | Small vessel disease | 420 vs 27 | PCB | TLR: 3.6% vs 4% | MACE: 4.7% vs 4.0% in 9 months | |||

| BELLO, Latib et al[31], 2012 | Small vessel disease | 182 | PEB vs PES | LLL: 0.08 ± 0.38 mm vs 0.29 ± 0.44 mm in 6-36 months | MACE: 10% vs 16%; 14.4% vs 30.4% | Restenosis rate: 10% vs 14.6% | TLR: 4.4% vs 7.6% | |

| PEPCAD I, Unverdorben et al[29], 2015 | Small vessel disease | 118 | DCB | LLL: 0.16 ± 0.38 mm with DCB vs 0.62 0.73 mm in DCB + BMS 6 months | 6.1% (DCB) vs 37.5% in DCB + DCB | 6% in DCB vs 45% in DCB + BMS at 36 months | TLR: 4.9% vs 28.1% at 36 months | |

| BASKET-SMALL 2, Jeger et al[34], 2018 | Small vessel disease | 758 | DCB vs DES | MACE: 7.5% vs 7.3% at 12 months | MACE: 15% vs 15% at 36 months | |||

| PICCOLETO II Cortese et al[54], 2020 | Small vessel disease | 232 | DCB vs EES | LLL: 0.04% vs 0.17% in 6-12 months | MACE: 5.6 vs 7.5% | |||

| FALCON, Widder et al[55], 2015 | De novo lesions | 326 | DCB | TLR: -4.9% at 12 months | MACE: 8% at 12 months | |||

| DEBUT, Rissanen et al[45], 2017 | High bleeding risk | 208 | DCB vs BMS | MACE: 1% vs 14%, at 9 months | TVR: 0% vs 6% at 9 months | |||

| FALCON, Widder et al[55], 2019 | ISR | 405 | DCB | TLR: -7.5% at 12 months | MACE: -11.1% at 12 months | |||

| DEBIUT, Stella et al[41], 2012 | Bifurcation | 20 | PCB in SB and MB plus BMS in MB, BMS in MB, PES in MB | LLL in proximal MB, distal MB and SB were lowest in PES arm | Binary restenosis rates: -24.2%, 28.6%, and 15% | MACE rates: -20%, 29.7%, and 17.5% | ||

| PEPCAD V, Mathey et al[56], 2011 | Bifurcation | 28 | DCB in SB and MB followed by BMS in MB | Procedural success in 100% | LLL at 9 months -0.38 ± 0.46 mm MB and 0.21 ± 0.48 mm in SB; binary restenosis rates -3.8% in MB and 7.7% in SB | |||

| Herrador et al[40], 2012 | Bifurcation | 100 | DES in MB, PCB in SB vs DES in MB, POBA in SB | LLL in SB: 0.09 ± 0.4 mm vs 0.40 ± 0.5 mm at 12 months | MACE: 11% vs 24%; TLR: 12% vs 22% | |||

| BABILON, López Mínguez et al[42], 2014 | Bifurcation | 108 | BMS in MB, PCB in SB vs DES in MB | LLL in MB: 0.31 ± 0.48mm vs 0.16 ± 0.38 mm; LLL in SB: -0.03 ± 0.51 mm vs 0.04 ± 0.76 mm at 9 months | MACE: 17.3% vs 7.1%; TLR: 15.4% vs 7.6% | |||

| PEPCAD-BIF, Kleber et al[44], 2016 | Bifurcation | 64 | DCB vs POBA in SB | LLL in SB: 0.13 ± 0.51 mm | Re-stenosis rate: 6% vs 26% | |||

| DCB-BIF, Gao et al[57], 202 | Bifurcation | 784 | DES in MB, DCB vs NCB in SB | MACE: 7.2% vs 12.5%; P = 0.013 | MACE without periprocedural MI: -2.6% vs 5.1%; target vessel MI: 5.6% vs 10.9% | |||

The pathophysiology of restenosis following stent implantation differs from that observed after POBA. ISR after BMSs is primarily driven by neointimal hyperplasia, whereas ISR following DESs involves both neoatherosclerosis and hyperplasia. DCBs have demonstrated superiority over BMSs and DESs in treating ISR in multiple clinical trials (Table 2). Patients with DES-related ISR are a high-risk group because of the primary failure of drug delivery by the original stent[35]. PACCOCATH ISR was one of the initial studies with a paclitaxel DCB in 52 patients with DES ISR, pitching it against POBA[24]. At 6 months, the LLL was significantly lower with the DCB arm compared with balloon angioplasty (Table 2)[24,29,31,34,36-57]. Then the PEPCAD II ISR compared the paclitaxel DCB with a paclitaxel DES in 131 patients with DES ISR[36]. At 6 months, the LLL with DCB was significantly less than DES, and the benefits were sustained till 3 years. Then, the ISAR drug-eluting stent in-stent restenosis-3 evaluated the role of all 3-paclitaxel DES, paclitaxel DCB, and balloon angioplasty in 402 patients with DES restenosis[37]. At 8 months, paclitaxel DCB was non-inferior to paclitaxel DES for diameter stenosis. Both groups were superior to balloon angioplasty. Death, myocardial Infarction, and target lesion thrombosis were also similar in both groups. At 10-year follow-up, the primary composite end point of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, target lesion thrombosis, or target lesion revascularization was similar with paclitaxel DCB and DES, though there were signals of higher death with the DES arm compared to DCB at 5 years[38]. The relative efficacy of DCBs compared with DESs may vary depending on the underlying tissue substrate, namely, neointimal hyperplasia vs neoatherosclerosis. This distinction is supported by findings from large meta-analyses of RCTs, which show that DCBs are equivalent to DESs in reducing the need for revascularisation in BMS-related ISR but may be somewhat less effective in DES-related ISR. DCBs are particularly well-suited for patients with multiple prior stent layers, where preserving SBs is essential, and for those requiring shorter durations of DAPT due to high bleeding risk[39]. In light of these findings, current guidelines on myocardial revascularisation recommend the use of DCBs for the treatment of ISR (Class I, level of evidence: A)[28]. The various other trials of DCBs in ISR are described in Table 2.

The treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions remains challenging, primarily due to suboptimal angiographic and clinical outcomes, particularly in the SB. Even with the use of the latest-generation DESs, the risk of restenosis persists, especially when more complex techniques are employed. Consequently, a provisional bifurcation strategy involving stent implantation in the MB only has become the preferred approach, as supported by recent clinical trial data. However, treatment of the SB with a DCB may offer superior outcomes compared with POBA[40]. The DEBIUT study, a RCT involving 117 patients, compared three strategies: DCB pretreatment in both SB and MB, followed by BMS in MB; BMS in MB with an uncoated balloon in SB, and paclitaxel DES in MB with an uncoated balloon in SB[41]. Although favourable outcomes were observed in the DCB + BMS arm, it was not superior to BMS alone, largely due to the good results achieved with POBA-treated SBs in both the BMS and DES groups. In the multicentre BABILON RCT, both MACE and TLR rates were higher in the DCB group than in the DES group (17.3% vs 7.1%; P = 0.105 and 15.4% vs 3.6%; P = 0.045). These differences were attributed to greater, though nonsignificant, LLL in the MB with DCB pretreatment and BMS implantation compared with everolimus DES[42]. A DCB-only strategy has also been investigated in bifurcation lesions. The PEPCAD bifurcation trial, a multicentre RCT involving 64 patients, compared DCB-only treatment with POBA. The restenosis rate was significantly lower in the DCB group (6% vs 26%; P = 0.045). These results suggest that, with proper lesion preparation, a DCB-only strategy can be a viable treatment option for bifurcation lesions, achieving acceptable angiographic outcomes[43]. The details of various other DCB trials in bifurcation lesions are shown in Table 2.

Bleeding following PCI is a significant cause of both mortality and ischaemic events, including non-fatal myocardial infarction[19]. DCBs may be preferred over stent implantation in patients at high risk of bleeding, such as frail older individuals, those receiving anticoagulation therapy, patients with chronic kidney disease, or those with a known bleeding diathesis. Although the latest-generation DESs have enabled shorter durations of DAPT post-PCI, antithrombotic therapy can be discontinued even earlier after DCB use in cases of severe, life-threatening bleeding. Expert opinion recommends a DAPT duration of 4 weeks following a DCB-only strategy in de novo coronary vessels, with favourable outcomes reported in recent clinical trials involving stable patients[44]. According to data from several RCTs and registry studies involving 1500 patients, no cases of acute or subacute thrombosis were observed after DCB-only treatment[45]. Some studies have reported an acute thrombosis risk as low as 0.2% following DCB-only PCI[46]. Therefore, in patients requiring PCI who are at high risk of bleeding, such as those with a history of life-threatening hemorrhage or those scheduled for major surgery, a DCB-only strategy may be preferable due to its low associated thrombotic risk.

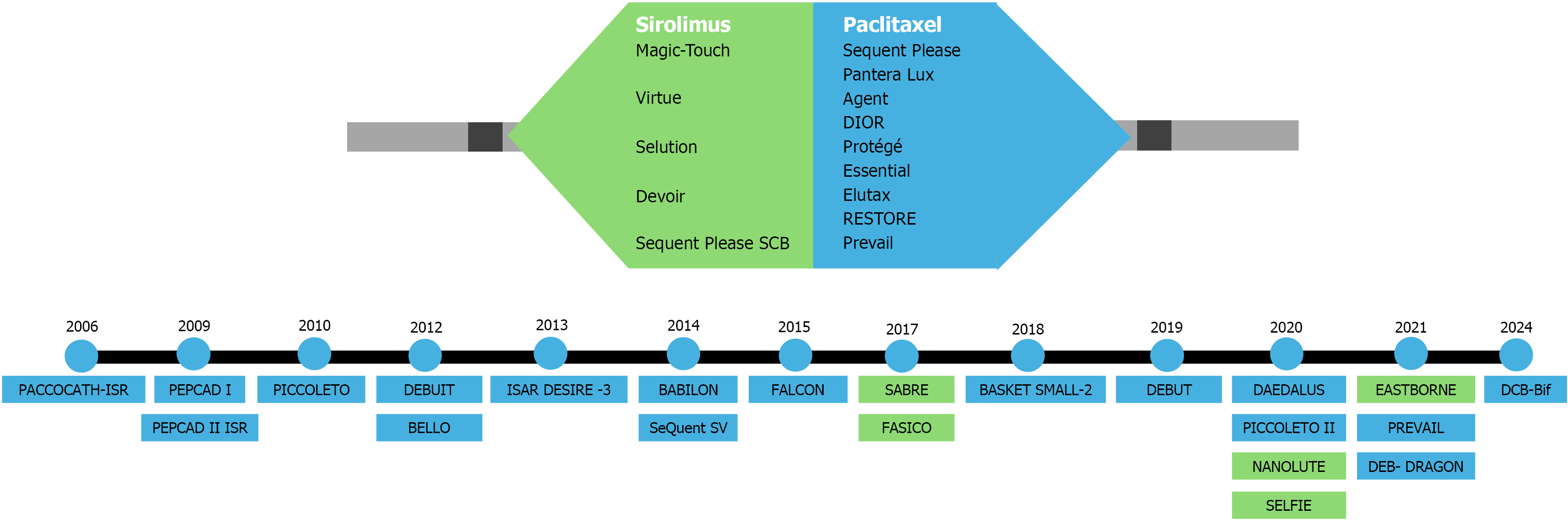

Stent length is an independent predictor of target lesion failure, manifesting as ISR and stent thrombosis[44]. PCI using overlapping DESs measuring ≥ 60 mm in total length has been associated with high TLR rates of up to 24%. In another study involving coronary lesions > 25 mm in length, outcomes with DCB therapy, using a DES only as a bailout, were comparable to those achieved with a DES-only approach. These findings suggest that DCB monotherapy, with selective DES use as a bailout strategy, is a viable and effective alternative for treating diffuse coronary disease while minimizing overall stent length[45]. The journey of various DCB trials in a variety of coronary lesions is depicted in Figure 1.

STENTLESS - Strategies of scheduled DCB vs conventional DES for the interventional therapy of de novo lesions in large coronary vessels trial (No. NCT06084000): This multicentre, open-label RCT is designed to compare the safety and efficacy of DCBs (paclitaxel-coated balloons) with conventional DESs for the treatment of de novo lesions in large coronary vessels (> 2.75 mm in diameter). The trial will enroll approximately 2700 participants and is expected to be completed by December 2025[58].

DCBNORWICH (No. NCT04482972): This is a retrospective cohort study comparing DES and DCB in an all-comer population. The primary endpoints include MACE, myocardial infarction and target vessel revascularization at 12 months.

OPEN-ISR study (Optimal treatment for coronary DES ISR) (No. NCT04862052): This open-label, randomized study aims to compare the safety and efficacy of DCB vs DES in the setting of DES-related ISR[59]. The study includes three treatment arms: Magic Touch - sirolimus-coated balloon, Emperor - paclitaxel- and dextran-coated balloon, and Xience- cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stent. All participants will undergo intravascular ultrasound-guided angioplasty.

LOVE DEB study (Large de Novo CAD Treated with sirolimus drug-eluting balloon) (No. NCT05915468): This post-market study investigates the Selution Sustained Limus Release sirolimus-eluting balloon for the treatment of de novo native CAD in large vessels (≥ 2.75 mm). Outcome measures include TLR, anginal symptoms, and all-cause mortality over a 1-year follow-up period[60].

DEBATE trial (Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty vs everolimus platinum chrome stent) (No. NCT05516446): This single-center, open-label, non-inferiority RCT compares DCB therapy with everolimus-eluting platinum-chromium stents in a Tunisian population undergoing PCI[61]. The primary outcome is LLL at 12 months.

DEBSCAN-IVL study (Drug-eluting balloon or DES to treat calcified nodules after intravascular lithotripsy) (No. NCT06657833): This international, investigator-driven, multicentre RCT evaluates the safety and efficacy of DCBs vs DES in patients with de novo lesions caused by calcified nodules[62]. The study plans to enroll 128 patients. Primary outcomes include LLL and net late lumen gain at 6 months, and safety endpoints include acute dissection, perforation, and abrupt vessel closure during PCI.

The DCB is a promising technology for coronary interventions. Its efficacy is particularly well supported in the treatment of ISR, especially in patients with multiple layers of stents, as well as in certain de novo coronary lesions. Although a substantial number of studies have explored various clinical applications of DCBs, there remains a lack of large RCTs and meta-analyses. To better establish the role of DCBs in routine clinical practice, large-scale trials with broad inclusion criteria are urgently needed.

| 1. | Murphy E, Rahimtoola SH. Transluminal dilatation for coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet. 1978;1:1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Canfield J, Totary-Jain H. 40 Years of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: History and Future Directions. J Pers Med. 2018;8:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Grech ED. ABC of interventional cardiology: percutaneous coronary intervention. I: history and development. BMJ. 2003;326:1080-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fischman DL, Leon MB, Baim DS, Schatz RA, Savage MP, Penn I, Detre K, Veltri L, Ricci D, Nobuyoshi M. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:496-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3153] [Cited by in RCA: 2985] [Article Influence: 93.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, Macaya C, Rutsch W, Heyndrickx G, Emanuelsson H, Marco J, Legrand V, Materne P. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3312] [Cited by in RCA: 3124] [Article Influence: 97.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | O' Brien ER, Ma X, Simard T, Pourdjabbar A, Hibbert B. Pathogenesis of neointima formation following vascular injury. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban Hayashi E, Perin M, Colombo A, Schuler G, Barragan P, Guagliumi G, Molnàr F, Falotico R; RAVEL Study Group. Randomized Study with the Sirolimus-Coated Bx Velocity Balloon-Expandable Stent in the Treatment of Patients with de Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3050] [Cited by in RCA: 2900] [Article Influence: 120.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O'Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE; SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3272] [Cited by in RCA: 3130] [Article Influence: 136.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cannon L, Mann JT, Greenberg JD, Spriggs D, O'Shaughnessy CD, DeMaio S, Hall P, Popma JJ, Koglin J, Russell ME; TAXUS V Investigators. Comparison of a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1215-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 577] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stone GW, Ellis SG, Colombo A, Grube E, Popma JJ, Uchida T, Bleuit JS, Dawkins KD, Russell ME. Long-term safety and efficacy of paclitaxel-eluting stents final 5-year analysis from the TAXUS Clinical Trial Program. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:530-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E, Cheneau E, Ong AT, Kinnaird T, Suddath WO, Weissman NJ, Torguson R, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Waksman R, Serruys PW. Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 2004;364:1519-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1065] [Cited by in RCA: 1011] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Onuma Y, Miquel-Hebert K, Serruys PW; SPIRIT II Investigators. Five-year long-term clinical follow-up of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting coronary stent system in the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery disease: the SPIRIT II trial. EuroIntervention. 2013;8:1047-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kelly CR, Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, Farah B, Dubois CL, Feldman RL, Dens J, Hagiwara N, Rabinowitz A, Carrié D, Pompili V, Bouchard A, Saito S, Allocco DJ, Dawkins KD, Stone GW. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Platinum Chromium Everolimus-Eluting Stents in Coronary Artery Disease: 5-Year Results From the PLATINUM Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:2392-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oberhauser JP, Hossainy S, Rapoza RJ. Design principles and performance of bioresorbable polymeric vascular scaffolds. EuroIntervention. 2009;5 Suppl F:F15-F22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gogas BD. Bioresorbable scaffolds for percutaneous coronary interventions. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014:409-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wykrzykowska JJ, Kraak RP, Hofma SH, van der Schaaf RJ, Arkenbout EK, IJsselmuiden AJ, Elias J, van Dongen IM, Tijssen RYG, Koch KT, Baan J Jr, Vis MM, de Winter RJ, Piek JJ, Tijssen JGP, Henriques JPS; AIDA Investigators. Bioresorbable Scaffolds versus Metallic Stents in Routine PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2319-2328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Metzger C, Caputo RP, Rizik DG, Teirstein PS, Litt MR, Kini A, Kabour A, Marx SO, Popma JJ, McGreevy R, Zhang Z, Simonton C, Stone GW; ABSORB III Investigators. 3-Year Clinical Outcomes With Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Coronary Scaffolds: The ABSORB III Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2852-2862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nishida T, Colombo A, Briguori C, Stankovic G, Albiero R, Corvaja N, Finci L, Di Mario C, Tobis JM. Outcome of nonobstructive residual dissections detected by intravascular ultrasound following percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1257-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sorrentino S, Sartori S, Baber U, Claessen BE, Giustino G, Chandrasekhar J, Chandiramani R, Cohen DJ, Henry TD, Guedeney P, Ariti C, Dangas G, Gibson CM, Krucoff MW, Moliterno DJ, Colombo A, Vogel B, Chieffo A, Kini AS, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Steg PG, Pocock S, Urban P, Mehran R. Bleeding Risk, Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Cessation, and Adverse Events After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The PARIS Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e008226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pelliccia F, Zimarino M, Niccoli G, Morrone D, De Luca G, Miraldi F, De Caterina R. In-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention: emerging knowledge on biological pathways. Eur Heart J Open. 2023;3:oead083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 21. | Narbute I, Jegere S, Kumsārs I, Juhnēviča D, Knipse A, Erglis A. Real-life Bifurcation - Challenges and Potential Complications. Interv Cardiol. 2011;7:283. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gao L, Chen YD. Application of drug-coated balloon in coronary artery intervention: challenges and opportunities. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:906-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, Ge J, Poerner TC, Shin ES, Alfonso F, Latib A, Ong PJ, Rissanen TT, Saucedo J, Scheller B, Kleber FX; International DCB Consensus Group. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease: Third Report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W, Rutsch W, Haghi D, Dietz U, Böhm M, Speck U. Treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2113-2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Lemos PA, Farooq V, Takimura CK, Gutierrez PS, Virmani R, Kolodgie F, Christians U, Kharlamov A, Doshi M, Sojitra P, van Beusekom HM, Serruys PW. Emerging technologies: polymer-free phospholipid encapsulated sirolimus nanocarriers for the controlled release of drug from a stent-plus-balloon or a stand-alone balloon catheter. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Verheye S, Vrolix M, Kumsars I, Erglis A, Sondore D, Agostoni P, Cornelis K, Janssens L, Maeng M, Slagboom T, Amoroso G, Jensen LO, Granada JF, Stella P. The SABRE Trial (Sirolimus Angioplasty Balloon for Coronary In-Stent Restenosis): Angiographic Results and 1-Year Clinical Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:2029-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ali RM, Abdul Kader MASK, Wan Ahmad WA, Ong TK, Liew HB, Omar AF, Mahmood Zuhdi AS, Nuruddin AA, Schnorr B, Scheller B. Treatment of Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis by a Sirolimus- or Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Falk V, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ, Seferovic PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2722] [Cited by in RCA: 4795] [Article Influence: 799.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Unverdorben M, Kleber FX, Heuer H, Figulla HR, Vallbracht C, Leschke M, Cremers B, Hardt S, Buerke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Degenhardt R, Scheller B. Treatment of small coronary arteries with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Unverdorben M, Kleber FX, Heuer H, Figulla HR, Vallbracht C, Leschke M, Cremers B, Hardt S, Buerke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Degenhardt R, Scheller B. Treatment of small coronary arteries with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter in the PEPCAD I study: are lesions clinically stable from 12 to 36 months? EuroIntervention. 2013;9:620-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Latib A, Colombo A, Castriota F, Micari A, Cremonesi A, De Felice F, Marchese A, Tespili M, Presbitero P, Sgueglia GA, Buffoli F, Tamburino C, Varbella F, Menozzi A. A randomized multicenter study comparing a paclitaxel drug-eluting balloon with a paclitaxel-eluting stent in small coronary vessels: the BELLO (Balloon Elution and Late Loss Optimization) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2473-2480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Latib A, Ruparelia N, Menozzi A, Castriota F, Micari A, Cremonesi A, De Felice F, Marchese A, Tespili M, Presbitero P, Sgueglia GA, Buffoli F, Tamburino C, Varbella F, Colombo A. 3-Year Follow-Up of the Balloon Elution and Late Loss Optimization Study (BELLO). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1132-1134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zeymer U, Waliszewski M, Spiecker M, Gastmann O, Faurie B, Ferrari M, Alidoosti M, Palmieri C, Heang TN, Ong PJ, Dietz U. Prospective 'real world' registry for the use of the 'PCB only' strategy in small vessel de novo lesions. Heart. 2014;100:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, Mangner N, Möbius-Winkler S, Leibundgut G, Weilenmann D, Wöhrle J, Richter S, Schreiber M, Mahfoud F, Linke A, Stephan FP, Mueller C, Rickenbacher P, Coslovsky M, Gilgen N, Osswald S, Kaiser C, Scheller B; BASKET-SMALL 2 Investigators. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392:849-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Byrne RA, Cassese S, Windisch T, King LA, Joner M, Tada T, Mehilli J, Pache J, Kastrati A. Differential relative efficacy between drug-eluting stents in patients with bare metal and drug-eluting stent restenosis; evidence in support of drug resistance: insights from the ISAR-DESIRE and ISAR-DESIRE 2 trials. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:797-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, Cremers B, Heuer H, Hengstenberg C, Maikowski C, Werner GS, Antoni D, Kleber FX, Bocksch W, Leschke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Speck U, Degenhardt R, Scheller B. Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel-coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: the three-year results of the PEPCAD II ISR study. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:926-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, Pinieck S, Wolff B, Tiroch K, Schulz S, Fusaro M, Ott I, Ibrahim T, Hausleiter J, Valina C, Pache J, Laugwitz KL, Massberg S, Kastrati A; ISAR-DESIRE 3 investigators. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2013;381:461-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Giacoppo D, Alvarez-Covarrubias HA, Koch T, Cassese S, Xhepa E, Kessler T, Wiebe J, Joner M, Hochholzer W, Laugwitz KL, Schunkert H, Kastrati A, Kufner S. Coronary artery restenosis treatment with plain balloon, drug-coated balloon, or drug-eluting stent: 10-year outcomes of the ISAR-DESIRE 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:1343-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Alfonso F, Byrne RA, Rivero F, Kastrati A. Current treatment of in-stent restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2659-2673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Herrador JA, Fernandez JC, Guzman M, Aragon V. Drug-eluting vs. conventional balloon for side branch dilation in coronary bifurcations treated by provisional T stenting. J Interv Cardiol. 2013;26:454-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Stella PR, Belkacemi A, Dubois C, Nathoe H, Dens J, Naber C, Adriaenssens T, van Belle E, Doevendans P, Agostoni P. A multicenter randomized comparison of drug-eluting balloon plus bare-metal stent versus bare-metal stent versus drug-eluting stent in bifurcation lesions treated with a single-stenting technique: six-month angiographic and 12-month clinical results of the drug-eluting balloon in bifurcations trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:1138-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | López Mínguez JR, Nogales Asensio JM, Doncel Vecino LJ, Sandoval J, Romany S, Martínez Romero P, Fernández Díaz JA, Fernández Portales J, González Fernández R, Martínez Cáceres G, Merchán Herrera A, Alfonso Manterola F; BABILON Investigators. A prospective randomised study of the paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter in bifurcated coronary lesions (BABILON trial): 24-month clinical and angiographic results. EuroIntervention. 2014;10:50-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kleber FX, Rittger H, Ludwig J, Schulz A, Mathey DG, Boxberger M, Degenhardt R, Scheller B, Strasser RH. Drug eluting balloons as stand alone procedure for coronary bifurcational lesions: results of the randomized multicenter PEPCAD-BIF trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105:613-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kleber F, Scheller B, Ong P, Rissanen T, Zeymer U, Wöhrle J, Komatsu T, Simon Eccleshall, Köln P, Colombo A, Kornowski R. TCT-776 Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-coated balloon implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:B309-B310. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rissanen TT, Uskela S, Eränen J, Mäntylä P, Olli A, Romppanen H, Siljander A, Pietilä M, Minkkinen MJ, Tervo J, Kärkkäinen JM; DEBUT trial investigators. Drug-coated balloon for treatment of de-novo coronary artery lesions in patients with high bleeding risk (DEBUT): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394:230-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Uskela S, Kärkkäinen JM, Eränen J, Siljander A, Mäntylä P, Mustonen J, Rissanen TT. Percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-coated balloon-only strategy in stable coronary artery disease and in acute coronary syndromes: An all-comers registry study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | D'Ascenzo F, Bollati M, Clementi F, Castagno D, Lagerqvist B, de la Torre Hernandez JM, ten Berg JM, Brodie BR, Urban P, Jensen LO, Sardi G, Waksman R, Lasala JM, Schulz S, Stone GW, Airoldi F, Colombo A, Lemesle G, Applegate RJ, Buonamici P, Kirtane AJ, Undas A, Sheiban I, Gaita F, Sangiorgi G, Modena MG, Frati G, Biondi-Zoccai G. Incidence and predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: evidence from an international collaborative meta-analysis including 30 studies, 221,066 patients, and 4276 thromboses. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:575-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Venetsanos D, Lawesson SS, Panayi G, Tödt T, Berglund U, Swahn E, Alfredsson J. Long-term efficacy of drug coated balloons compared with new generation drug-eluting stents for the treatment of de novo coronary artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:E317-E326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Scheller B, Fontaine T, Mangner N, Hoffmann S, Bonaventura K, Clever YP, Chamie D, Costa R, Gershony G, Kelsch B, Kutschera M, Généreux P, Cremers B, Böhm M, Speck U, Abizaid A. A novel drug-coated scoring balloon for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: Results from the multi-center randomized controlled PATENT-C first in human trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Rittger H, Brachmann J, Sinha AM, Waliszewski M, Ohlow M, Brugger A, Thiele H, Birkemeyer R, Kurowski V, Breithardt OA, Schmidt M, Zimmermann S, Lonke S, von Cranach M, Nguyen TV, Daniel WG, Wöhrle J. A randomized, multicenter, single-blinded trial comparing paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty with plain balloon angioplasty in drug-eluting stent restenosis: the PEPCAD-DES study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1377-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Rittger H, Waliszewski M, Brachmann J, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Ohlow M, Brugger A, Thiele H, Birkemeyer R, Kurowski V, Schlundt C, Zimmermann S, Lonke S, von Cranach M, Markovic S, Daniel WG, Achenbach S, Wöhrle J. Long-Term Outcomes After Treatment With a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Versus Balloon Angioplasty: Insights From the PEPCAD-DES Study (Treatment of Drug-eluting Stent [DES] In-Stent Restenosis With SeQuent Please Paclitaxel-Coated Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty [PTCA] Catheter). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1695-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kufner S, Joner M, Schneider S, Tölg R, Zrenner B, Repp J, Starkmann A, Xhepa E, Ibrahim T, Cassese S, Fusaro M, Ott I, Hengstenberg C, Schunkert H, Abdel-Wahab M, Laugwitz KL, Kastrati A, Byrne RA; ISAR-DESIRE 4 Investigators. Neointimal Modification With Scoring Balloon and Efficacy of Drug-Coated Balloon Therapy in Patients With Restenosis in Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1332-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Cortese B, Micheli A, Picchi A, Coppolaro A, Bandinelli L, Severi S, Limbruno U. Paclitaxel-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent during PCI of small coronary vessels, a prospective randomised clinical trial. The PICCOLETO study. Heart. 2010;96:1291-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cortese B, Di Palma G, Guimaraes MG, Piraino D, Orrego PS, Buccheri D, Rivero F, Perotto A, Zambelli G, Alfonso F. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small Coronary Vessel Disease: PICCOLETO II Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2840-2849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Widder JD, Cortese B, Levesque S, Berliner D, Eccleshall S, Graf K, Doutrelant L, Ahmed J, Bressollette E, Zavalloni D, Piraino D, Roguin A, Scheller B, Stella PR, Bauersachs J. Coronary artery treatment with a urea-based paclitaxel-coated balloon: the European-wide FALCON all-comers DCB Registry (FALCON Registry). EuroIntervention. 2019;15:e382-e388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mathey DG, Wendig I, Boxberger M, Bonaventura K, Kleber FX. Treatment of bifurcation lesions with a drug-eluting balloon: the PEPCAD V (Paclitaxel Eluting PTCA Balloon in Coronary Artery Disease) trial. EuroIntervention. 2011;7 Suppl K:K61-K65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gao X, Tian N, Kan J, Li P, Wang M, Sheiban I, Figini F, Deng J, Chen X, Santoso T, Shin ES, Munawar M, Wen S, Wang Z, Nie S, Li Y, Xu T, Wang B, Ye F, Zhang J, Shou X, Chen SL. Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty of the Side Branch During Provisional Stenting: The Multicenter Randomized DCB-BIF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | China National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases. STrategies of Scheduled Drug-coated Balloons (DCB) Versus Conventional DES for the interveNTional Therapy of de Novo Lesions in Large Coronary vESSels (STENTLESS) Trial (STENTLESS). [accessed 2025 Oct 24]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available online from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06084000. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06084000. |

| 59. | Kulyassa PM, Németh BT, Hizoh I, Jankó LK, Ruzsa Z, Jambrik Z, Balázs BB, Becker D, Merkely B, Édes IF. The Design and Feasibility of Optimal Treatment for Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent In-Stent Restenosis (OPEN-ISR)-A Prospective, Randomised, Multicentre Clinical Trial. J Pers Med. 2025;15:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust. Large De-NOVo Coronary artEry Disease Treated With Sirolimus Drug Eluting Balloon (LOVE DEB). [accessed 2025 Oct 24]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05915468 ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05915468. |

| 61. | General Administration of Military Health, Tunisia. Drug Eluting Balloon Angioplasty Versus Everolimus Platinum Chrome Stent (DEBATE). [accessed 2025 Oct 24]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05516446 ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05516446. |

| 62. | Fundación EPIC. Drug Eluting Balloon or Drug Eluting Stent to Treat CAlcified Nodules After IntraVascular Lithotripsy. (DEBSCAN-IVL). [accessed 2025 Oct 24]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06657833 ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06657833. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/