Published online Aug 26, 2021. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v13.i8.237

Peer-review started: April 15, 2021

First decision: May 13, 2021

Revised: May 27, 2021

Accepted: July 9, 2021

Article in press: July 9, 2021

Published online: August 26, 2021

Processing time: 130 Days and 5.3 Hours

During the last years two questions have been continuously asked in chronic coronary syndromes: (1) Do revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) really improve symptoms of angina? and (2) Do these techniques improve outcomes, i.e. do they prevent new myocardial infarction events and cardiovascular death? Therefore, there was a need for a large definitive trial. This study was the ISCHEMIA trial, a large, multicentric trial sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The main trial compared coronary revascularization and optimal medical treatment (OMT) vs OMT alone in 5179 patients enrolled after a stress test. During a median 3.2-year follow-up, 318 primary outcome events occurred; the adjusted hazard ratio for the invasive strategy as compared with the conservative strategy was 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.80-1.08, P = 0.34). The ISCHEMIA trial deeply disrupted many of our prior attitudes regarding management strategies for patients with stable coronary artery disease. The findings underscore the benefits of disease-modifying OMT for stable coronary artery disease patients. The main purposes of ischemia assessment before this trial were: Diagnostic purposes, assessment of outcome, and adding to decision-making processes. Obviously, this changed after the trial results. The results of ISCHEMIA might challenge the current diagnostic approach for stable angina patients recommended in the last European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary disease that were based on studies published before the ISCHEMIA trial. In this editorial we propose our approach based on the ISCHEMIA study and the pretest probability for a positive test in patients with chronic coronary syndromes.

Core Tip: During the last years two questions have been continuously asked in chronic coronary syndromes: Do revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) really improve symptoms of angina? Do these techniques improve outcomes, i.e. do they prevent new myocardial infarction events and cardiovascular death? The results of ISCHEMIA might challenge the current diagnostic approach for stable angina patients recommended in the last European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary disease that were based on studies published before the ISCHEMIA trial. In this editorial we propose our approach based on the ISCHEMIA study and the pretest probability for a positive test in patients with chronic coronary syndromes.

- Citation: Vidal-Perez R, Bouzas-Mosquera A, Peteiro J, Vazquez-Rodriguez JM. ISCHEMIA trial: How to apply the results to clinical practice. World J Cardiol 2021; 13(8): 237-242

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v13/i8/237.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v13.i8.237

Since the first definition of angina by the English physician William Heberden in 1772[1] many aspects have been discussed about this entity. Heberden described with a lot of detail a symptom, but he did not comprehend the disease. Later, in 1793, Edward Jenner detected thickened coronary arteries at an autopsy of his colleague John Hunter after sudden cardiac death due to an angina attack[2]. It took decades to get a first treatment (amyl nitrite)[3] for angina pectoris, and it was an even greater time for a valid understanding of the underlying disorder.

In 1967, Favaloro[4] used a saphenous vein and sewed it to the narrowing diseased coronary artery, making this the first coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Certainly, CABG showed a marked improvement of symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). In 1979, Andreas Grüntzig performed the first percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty[5]; later this technique has been known as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with the use of stents.

During the last years two questions have been continuously asked: (1) Do revascularization procedures (CABG or PCI) really improve symptoms of angina? and (2) Do these techniques improve outcomes, i.e. do they prevent new myocardial infarction events and cardiovascular death?

The initial enthusiasm for PCI was diminished after COURAGE trial[6], which showed no benefit of revascularization over optimal medical treatment (OMT). Nevertheless, the study was criticized due to a small proportion of the recruited patients treated in the participating centers and the use of bare metal stents. Then came the ORBITA trial[7] comparing OMT with PCI, this time using drug-eluting stents in a sham-controlled design, and the final result again was neutral. Once more, the same criticisms about small sample size were raised, and while symptoms and exercise tolerance only showed a tendency, regional wall motion was improved substantially in the stress echocardiograms[8].

Therefore, because of this uncertainly, there was a need for a large definitive trial. This study was the ISCHEMIA trial, which was presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in November 2019, and some months later it was published in the New England Journal of Medicine[9].

ISCHEMIA trial is a large, multicentric trial sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The main trial compared coronary revascularization and OMT vs OMT alone in 5179 patients enrolled after a stress test[9]. Related to this trial was the ISCHEMIA-CKD in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which had a similar design to the ISCHEMIA trial except that the use of a computed tomography (CT) scan was not necessary[10], and the CIAO-ISCHEMIA (Changes in Ischaemia and Angina over One year), which was a registry of patients excluded from the ISCHEMIA trial because of a negative CT scan. These latter patients represented around 14% of those initially considered for the ISCHEMIA trial and ultimately considered as ischemia with normal coronary arteries (INOCA)[11]. Moreover there was a quality of life study in the main ISCHEMIA trial, which included 4617 patients[12] that brought interesting results.

The rationale of the trial was clearly stated by the authors in the study abstract, “among patients with stable coronary disease and moderate or severe ischemia, whether clinical outcomes are better in those who receive an invasive intervention plus medical therapy than in those who receive medical therapy alone is uncertain”[9].

One key element of the trial was the performance of a blinded coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) prior to enrolment to exclude the presence of left main CAD and the absence of obstructive CAD.

We could consider this trial as the largest comparative effectiveness trial of an invasive vs conservative strategy in patients with stable coronary disease. It is important to highlight a recent terminology change; these stable patients are now known as patients with chronic coronary syndromes due to a new definition of the European Society of Cardiology[13].

The ISCHEMIA study has tried to address the key limitations of previous trials, namely: Recruiting high-risk patients with at least moderate inducible ischemia at baseline, randomizing patients prior to the diagnostic coronary angiogram to reduce both selection and referral bias, incorporating the current state-of the-art revascularization techniques that include the fractional flow reserve-guided PCI and the last generation drug-eluting stents at high-volume interventional sites who were selected for their proficiency and skill in revascularization, and employing an algorithm-based OMT and guidance for intensifying therapies in both arms of the trial.

The primary outcome of the trial was a five-component composite endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), hospitalization for unstable angina, hospitalization for heart failure, and resuscitated cardiac arrest, whereas the major secondary endpoints were time to cardiovascular death or non-fatal MI, anginal symptoms, and quality of life.

During a median 3.2-year follow-up, 318 primary outcome events occurred; the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the invasive strategy as compared with the conservative strategy was 0.93 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.80-1.08, P = 0.34]. There was no heterogeneity of treatment effect based on a broad range of pre-specified subgroups, including the presence of diabetes mellitus, high rate of OMT attainment, new or more frequent angina, degree of baseline ischemia, CAD severity based on 50% stenosis (i.e. one, two, or three vessel disease) or the presence of proximal left anterior descending coronary stenosis > 50%

There was no significant difference in total death for the invasive strategy (n = 145) group vs the conservative strategy (n = 144) group (HR = 1.05, 95%CI: 0.83-1.32) or in cardiovascular death (HR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.66-1.15). There was also no significant difference in the rate of overall MI between the two treatment strategies (adjusted HR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.76-1.11), although there were more procedural infarctions in the invasive strategy arm in early follow-up and more spontaneous myocardial infarctions in the conservative strategy arm in the late follow-up period[9].

There were significant and lasting improvements in angina control and quality of life metrics with an invasive approach in those patients who had significant angina [consider as daily/weekly (20% of ISCHEMIA patients)], but more modest improve

In the companion ISCHEMIA trial study (ISCHEMIA-CKD) of patients with CKD (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/body surface area)[10], with the same entry criteria and randomized treatment strategies, there was similarly no significant difference in outcome results between invasive vs conservative arms for the primary or secondary endpoints, however the invasive arm was associated with a higher incidence of stroke than the conservative arm (HR = 3.76, 95%CI: 1.52-9.32, P = 0.004) and higher incidence of death or initiation of dialysis (HR = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.04-2.11, P =0.03). There were no significant or sustained benefits in relation with angina-related health status between the two arms.

The ISCHEMIA trial deeply disrupts many of our prior attitudes regarding management strategies for patients with stable CAD. The findings underscore the benefits of disease-modifying OMT for stable CAD patients, and this must be our most important focus. While revascularization will always have a crucial role in symptom relief and improving quality of life, our primary goal should be to reduce incident cardiovascular events by utilizing proven therapies that stabilize vulnerable coronary plaques and improve event-free survival.

The main purposes of ischemia assessment before this trial were: Diagnostic purposes, assessment of outcome, and adding to the decision-making processes. Obviously, this has changed after the trial results.

The results of this study cannot be applied to patients with a known higher risk, such as those with very severe symptoms, left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction < 35%), or left main disease, since these patients were excluded from the ISCHEMIA study. The authors of the study point out, however, that the selection was near to our daily practice patients; more than half of those included were patients with severe ischemia, and also almost half of them had multivessel disease and/or CAD that included the proximal left anterior descending artery, in whom before we went to invasive management without even considering another option.

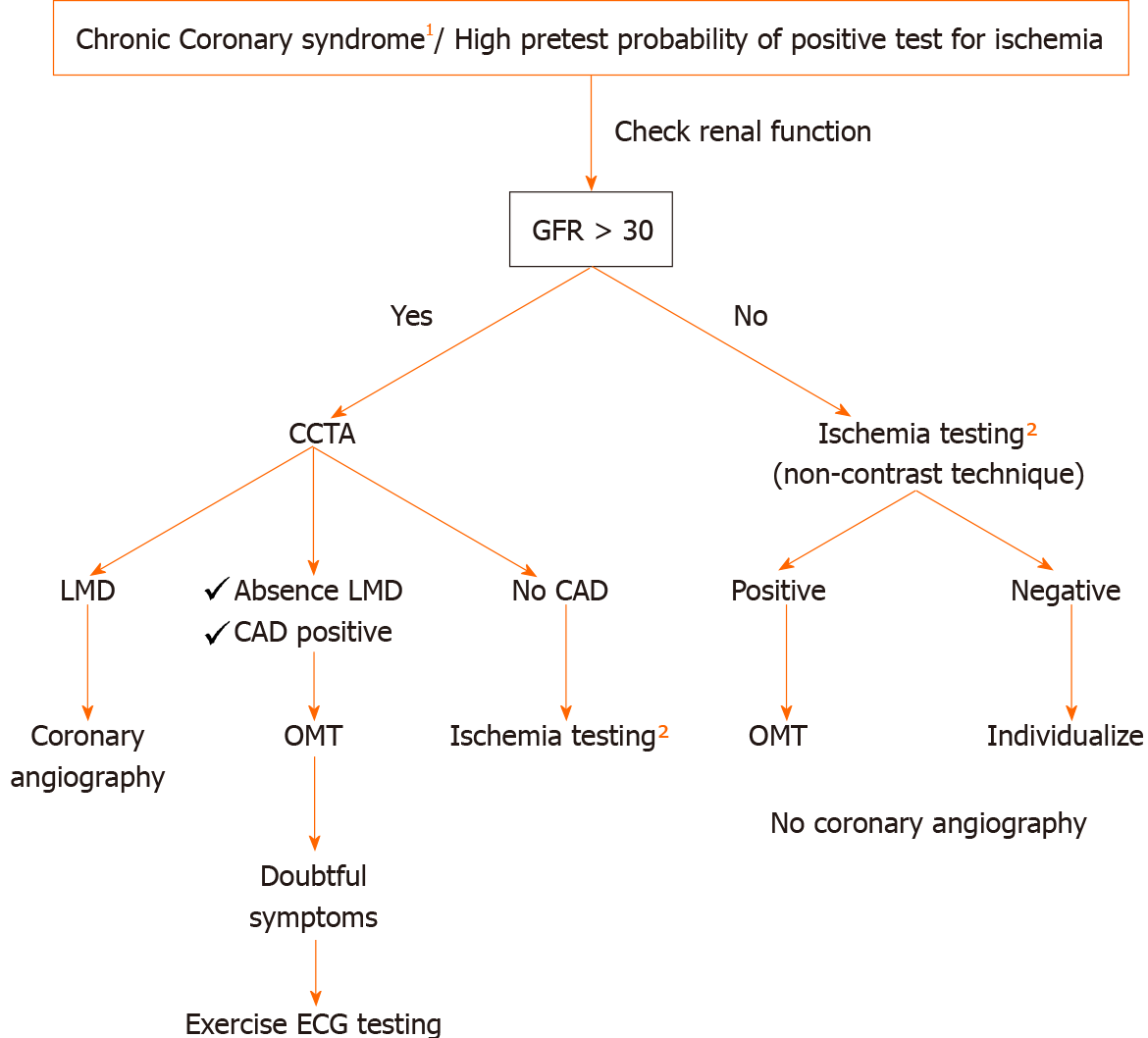

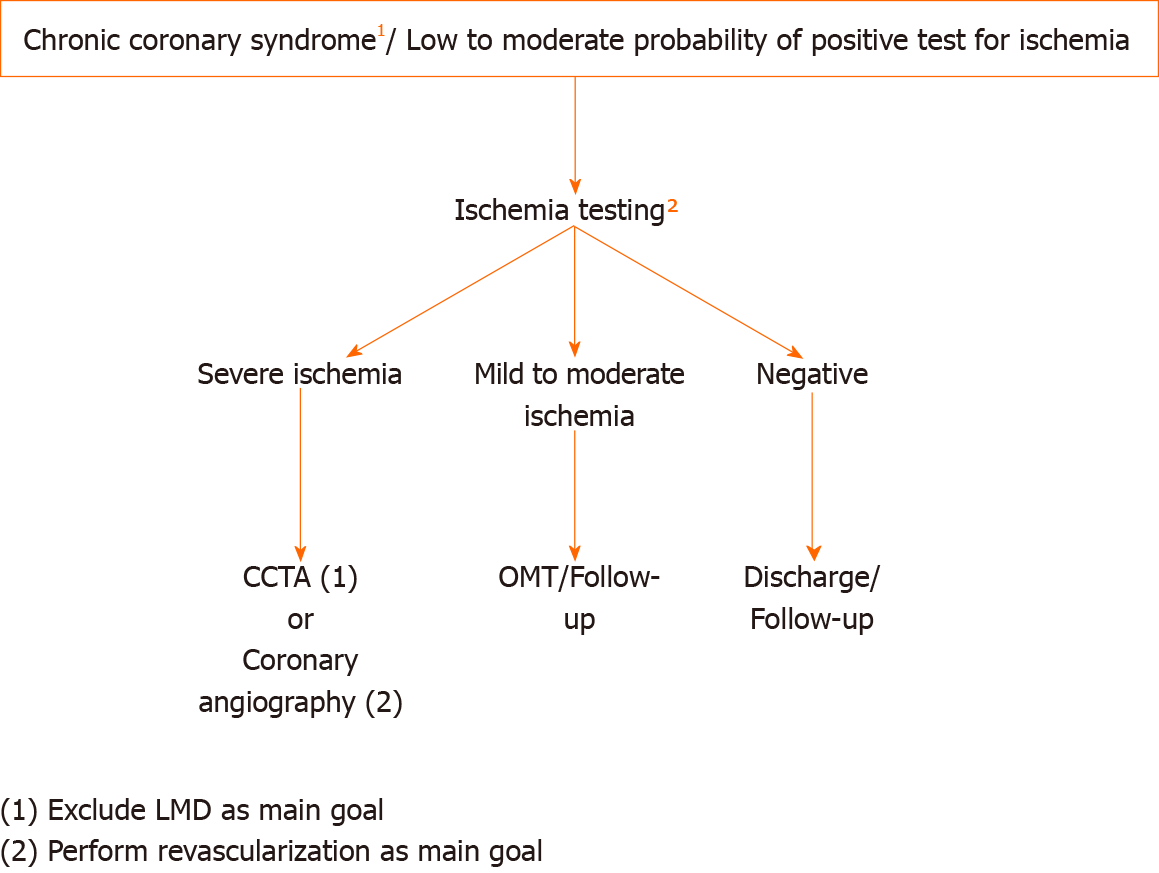

The results of ISCHEMIA and ISCHEMIA CKD might challenge the current diagnostic approach for stable angina patients recommended in the last European Society of Cardiology guidelines on chronic coronary disease[13] that were based on studies published before the ISCHEMIA trial. In the next two figures we propose our approach based on the ISCHEMIA study and the pretest probability for a positive test in patients with chronic coronary syndromes. Figure 1 shows our approach for high pretest probability patients where renal function needs to be known in advance, and Figure 2 can be applied for the low to moderate pretest probability patients. It should be pointed out that starting the work-out diagnosis by CCTA in every patient would miss a considerable number of patients with INOCA according to the combined ISCHEMIA and CIAO results (data not yet published)[11]. In addition, an initial CCTA approach would significantly increase the number of further functional tests due to unconclusive/positive CCTAs and spurious revascularizations[14]. Another important remark for a better comprehension of our approach is that according to the ISCHEMIA-CKD results, starting ischemia testing and trying to avoid coronary intervention seems desirable for patients with kidney dysfunction.

To summarize our view on stable coronary disease patients after the ISCHEMIA trial, the assessment of ischemia loses priority in this scenario, symptoms evaluation gains importance, and ischemia (and not anatomy) should be the focus in certain entities like CKD or INOCA[15].

| 1. | Heberden W. Some account of a disorder of the breast. Med Trans R Coll Phys Lond. 1772;2:59-67. |

| 2. | Osler W. Lectures on Angina Pectoris and Allied States: New York: D. Appleton; 1897. |

| 4. | Favaloro RG. Landmarks in the development of coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 1998;98:466-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meier B, Bachmann D, Lüscher T. 25 years of coronary angioplasty: almost a fairy tale. Lancet. 2003;361:527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GB, Weintraub WS; COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3259] [Cited by in RCA: 3264] [Article Influence: 171.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi HM, Sen S, Tang K, Davies J, Keeble T, Mielewczik M, Kaprielian R, Malik IS, Nijjer SS, Petraco R, Cook C, Ahmad Y, Howard J, Baker C, Sharp A, Gerber R, Talwar S, Assomull R, Mayet J, Wensel R, Collier D, Shun-Shin M, Thom SA, Davies JE, Francis DP; ORBITA investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 753] [Article Influence: 94.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Lamee RK, Shun-Shin MJ, Howard JP, Nowbar AN, Rajkumar C, Thompson D, Sen S, Nijjer S, Petraco R, Davies J, Keeble T, Tang K, Malik I, Bual N, Cook C, Ahmad Y, Seligman H, Sharp ASP, Gerber R, Talwar S, Assomull R, Cole G, Keenan NG, Kanaganayagam G, Sehmi J, Wensel R, Harrell FE Jr, Mayet J, Thom S, Davies JE, Francis DP. Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography Ischemia as a Predictor of the Placebo-Controlled Efficacy of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The Stress Echocardiography-Stratified Analysis of ORBITA. Circulation. 2019;140:1971-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, O'Brien SM, Boden WE, Chaitman BR, Senior R, López-Sendón J, Alexander KP, Lopes RD, Shaw LJ, Berger JS, Newman JD, Sidhu MS, Goodman SG, Ruzyllo W, Gosselin G, Maggioni AP, White HD, Bhargava B, Min JK, Mancini GBJ, Berman DS, Picard MH, Kwong RY, Ali ZA, Mark DB, Spertus JA, Krishnan MN, Elghamaz A, Moorthy N, Hueb WA, Demkow M, Mavromatis K, Bockeria O, Peteiro J, Miller TD, Szwed H, Doerr R, Keltai M, Selvanayagam JB, Steg PG, Held C, Kohsaka S, Mavromichalis S, Kirby R, Jeffries NO, Harrell FE Jr, Rockhold FW, Broderick S, Ferguson TB Jr, Williams DO, Harrington RA, Stone GW, Rosenberg Y; ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1110] [Cited by in RCA: 1891] [Article Influence: 315.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O'Brien SM, Fleg JL, Kretov EI, Briguori C, Kaul U, Reynolds HR, Mazurek T, Sidhu MS, Berger JS, Mathew RO, Bockeria O, Broderick S, Pracon R, Herzog CA, Huang Z, Stone GW, Boden WE, Newman JD, Ali ZA, Mark DB, Spertus JA, Alexander KP, Chaitman BR, Chertow GM, Hochman JS; ISCHEMIA-CKD Research Group. Management of Coronary Disease in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1608-1618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reynolds HR, Picard MH, Spertus JA, Peteiro J, Lopez-Sendon JL, Senior R, El-Hajjar MC, Celutkiene J, Shapiro MD, Pellikka PA, Kunichoff DF, Anthopolos R, Alfakih K, Abdul-Nour K, Khouri M, Bershtein L, De Belder M, Poh KK, Beltrame JF, Min JK, Fleg JL, Li Y, Maron DJ, Hochman JS. Natural History of Patients with Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: The CIAO-ISCHEMIA Study. Circulation. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, O'Brien SM, Reynolds HR, Rosenberg Y, Stone GW, Harrell FE Jr, Boden WE, Weintraub WS, Baloch K, Mavromatis K, Diaz A, Gosselin G, Newman JD, Mavromichalis S, Alexander KP, Cohen DJ, Bangalore S, Hochman JS, Mark DB; ISCHEMIA Research Group. Health-Status Outcomes with Invasive or Conservative Care in Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1408-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, Prescott E, Storey RF, Deaton C, Cuisset T, Agewall S, Dickstein K, Edvardsen T, Escaned J, Gersh BJ, Svitil P, Gilard M, Hasdai D, Hatala R, Mahfoud F, Masip J, Muneretto C, Valgimigli M, Achenbach S, Bax JJ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2791] [Cited by in RCA: 4807] [Article Influence: 801.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goyal A, Pagidipati N, Hill CL, Alhanti B, Udelson JE, Picard MH, Pellikka PA, Hoffmann U, Mark DB, Douglas PS. Clinical and Economic Implications of Inconclusive Noninvasive Test Results in Stable Patients With Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: Insights From the PROMISE Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:e009986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, Berry C, Escaned J, Maas AHEM, Prescott E, Karam N, Appelman Y, Fraccaro C, Louise Buchanan G, Manzo-Silberman S, Al-Lamee R, Regar E, Lansky A, Abbott JD, Badimon L, Duncker DJ, Mehran R, Capodanno D, Baumbach A. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-3520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 94.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kharlamov AN, Ueda H S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li X