Published online Oct 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i10.352

Revised: September 11, 2010

Accepted: September 18, 2010

Published online: October 27, 2010

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) of the pancreas include a spectrum of dysplasia ranging from minimal mucinous hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma and are extensive tumors that often spread along the ductal tree. Several studies have demonstrated that preoperative imaging is not accurate enough to adapt the extent of pancreatectomy and have suggested routinely using frozen sectioning (FS) to evaluate the completeness of resection and also to check if ductal dilatation is active or passive, in order to avoid an excessive pancreatic resection. Separate main duct and branch duct analysis is needed due to the difference in the natural history of the disease. FS accuracy averages 95%. Eroded epithelium on the main duct, severe ductal inflammation mimicking dysplasia and reactive epithelial changes secondary to obstruction can lead to inappropriate FS results. FS results change the planned extent of resection in up to 30% of cases. The optimal cut-off leading to extend pancreatectomy is not consensual and our standard option is to extend pancreatectomy if FS reveals: (1) at least IPMN adenoma on the main duct; or (2) at least borderline IPMN on branch ducts; or (3) invasive carcinoma. However, the decision to extend resection must be taken after a multidisciplinary discussion since it does not exclusively depend on the FS result but also on age, general condition and expected prognosis after resection. The main limitation of using FS is the existence of discontinuous (“skip”) lesions which account for approximately 10% of IPMN in surgical series and can lead to reoperation in up to 8% of cases.

- Citation: Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Belghiti J. Role of frozen section assessment for intraductal papillary and mucinous tumor of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(10): 352-358

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i10/352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i10.352

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) include a spectrum of dysplasia ranging from minimal mucinous hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma and are extensive tumors that often spread along the ductal tree[1-3].

Several studies have demonstrated that preoperative morphological assessment is not accurate enough to adapt the extent of pancreatectomy and have suggested routine use of frozen sectioning (FS) for this purpose[4-8]. This review is based on the pertinent literature and on the surgical and pathological experience of a single institution. We will first discuss the technical aspects of FS in surgery for IPMN. Since the surgical management of IPMN includes several procedures ranging from enucleation to total pancreatectomy, we will discuss successively the role and value of FS in each surgical technique. Finally, we expose the limitations and pitfalls of FS in this indication.

The most frequent type of surgery is partial pancreatectomy, usually pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) which accounts for about 60% of cases in surgical series[6,8,9].

Since diagnosis of IPMN is given by preoperative imaging in almost all cases, the need for FS and its implication in surgical strategy is known before surgery.

FS is performed either on the resected specimen or on a fresh slice of pancreatic cut surface harvested immediately after neck transection. In the latter setting, FS results can be obtained more rapidly during the procedure, thus allowing additional partial pancreatic resections and additional FS if needed. This may greatly reduce the length of surgery. In this setting, the surgeon must orientate the margin by guide mark stitches and identify the main duct if some branch ducts appear dilated.

All pancreatic transections for FS should be performed with a scalpel instead of electrocautery. The presence of either mucus or main duct dilatation at the level of transaction is not sufficient to indicate an additional pancreatic resection before the pathological results of FS[4]. In our opinion, it is not sufficient to only harvest one rim of main duct for FS since grading of dysplasia must be also performed in branch ducts[8].

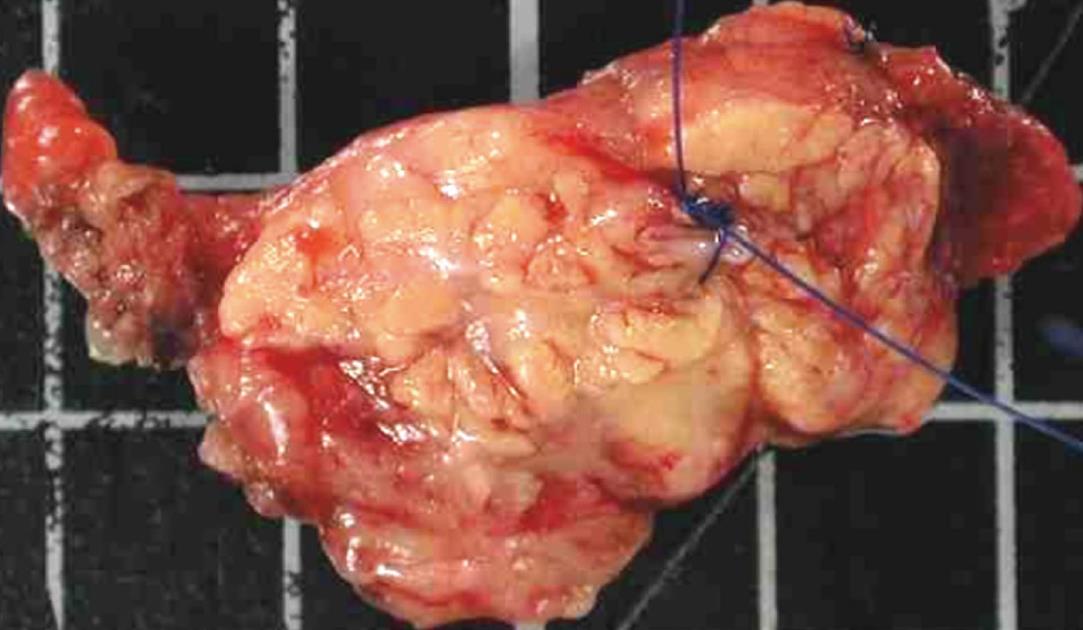

The pathologist must be aware of the suspected diagnosis of IPMN because the management of the sample is specific. The main duct must be identified macroscopically either in the PD specimen by catheterization or on a separate pancreatic slice by guide marks put by the surgeon (Figure 1). In addition, when the pancreatic slice is given separately, the side to be analyzed must have been indicated by the surgeon. The pathologist can ink the main duct to allow its definitive identification on histology because main duct lesions do not have the same clinical implication as branch duct lesions.

If the whole specimen has been also sent by the surgeon, it can be interesting to analyze its gross aspect and, if an area of possible malignant transformation which was not suspected by preoperative work-up is identified, it can be analyzed by FS, thus helping in the decision to perform an additional resection.

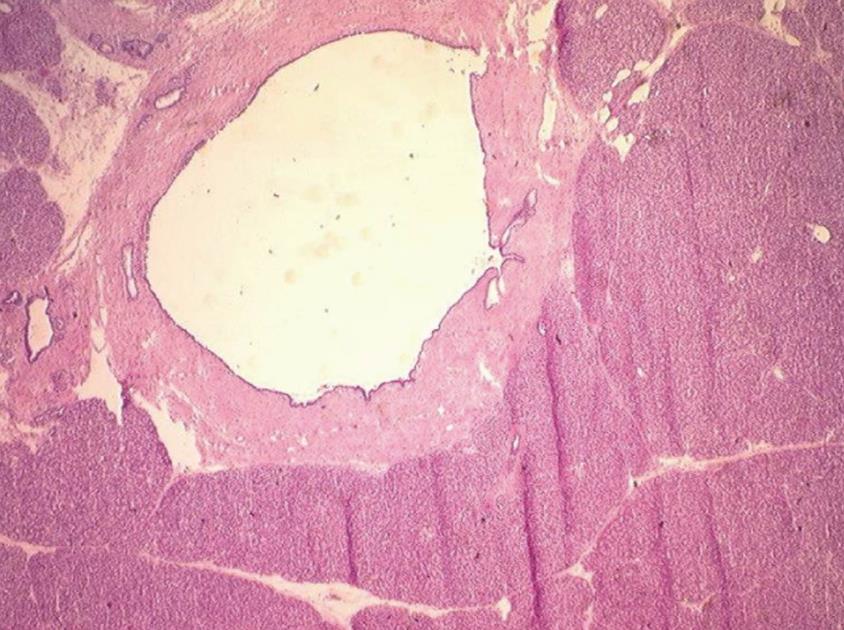

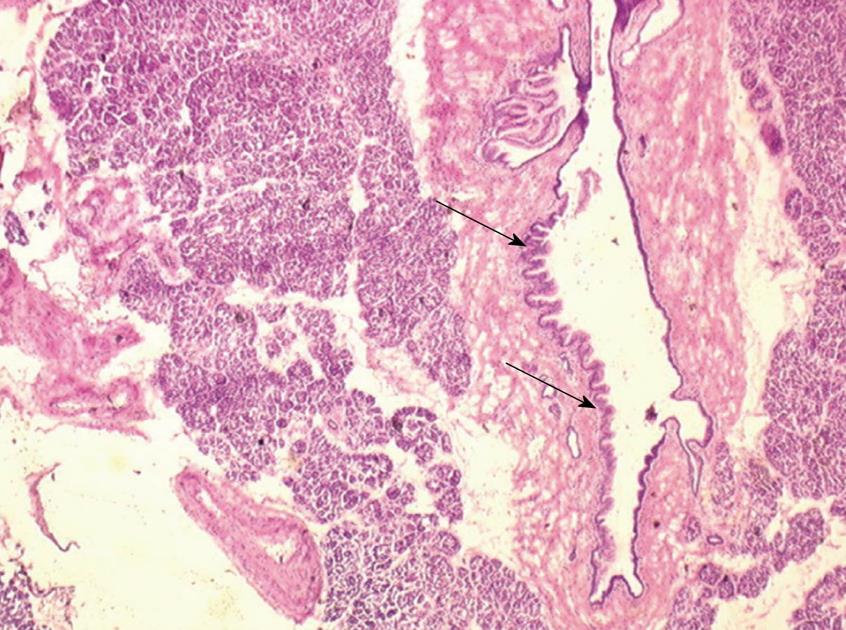

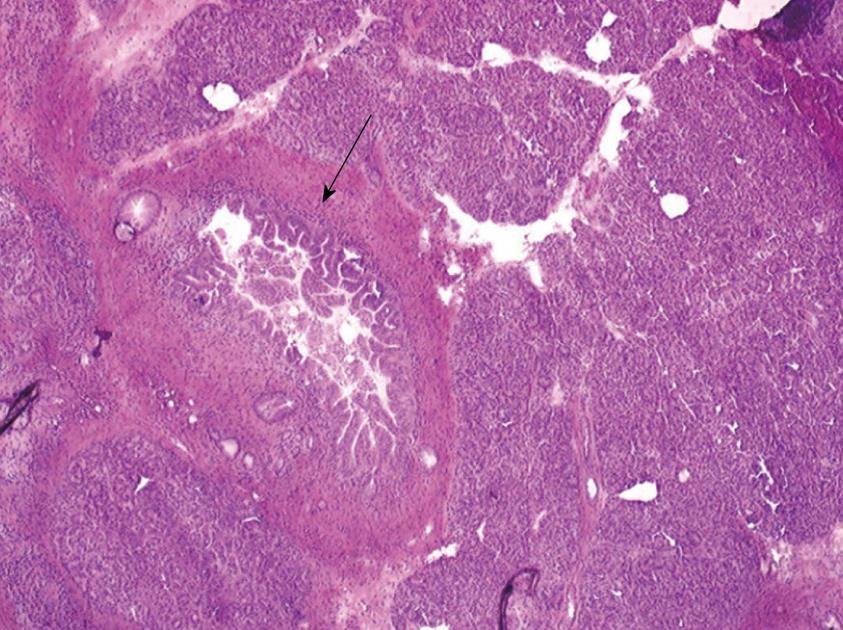

One 5 μm section is cut in a cryostat at -20°C, dried and colored by hematoxylin-eosin, mounted and analyzed under light microscopy. In case of eroded epithelium, several seriated sections are analyzed. The FS result includes description of both main duct and branch-ducts epithelium which can be normal or can include dysplastic changes ranging from low grade to high-grade dysplasia (Figures 2, 3, 4). Moreover, foci of invasive carcinoma are noted. In most cases, when the largest diameter of the sample is greater than 2 cm, it should be divided in two pieces after precise identification of the main duct in order to preserve the integrity of its wall. Histological diagnosis of dysplasia can be challenging, particularly in case of associated inflammation or pancreatitis. This diagnosis necessitates optimization of technical conditions, especially when the specimen is large and/or when fatty infiltration is present; for this purpose it may be useful to perform at least two or three seriated 5 μm sections.

Because of the frequent coexistence of various degrees of epithelial atypia, lesions are categorized in each type of duct (i.e. main duct and branch ducts) according to the most severe degree of dysplasia observed[8].The frozen-sectioned fragment is systematically fixed in formalin 10%, embedded in paraffin and analyzed for definitive histology.

The FS result must be transmitted by phone to the senior surgeon and written in both the pathological and the operative reports. Indeed, transmission of the FS result, if inaccurate, can be a source of inappropriate extent of pancreatic resection[8]. The decision not to extend resection or to perform an additional partial pancreatic resection must be consensual. If an additional pancreatic resection is needed, a subsequent FS is performed on the orientated additional specimen with the same protocol.

The main reasons for performing FS examination are to evaluate the completeness of resection and also to check if ductal dilatation is active or passive, in order to avoid an excessive pancreatic resection.

In this paragraph, we will firstly discuss the value of FS according to the degree of dysplasia and the location of IPMN lesions in branch and/or main ducts. Then we will give the specificities according to the type of resection (i.e. PD, distal pancreatectomy, medial pancreatectomy, enucleation and total pancreatectomy).

These guidelines apply mainly to non invasive IPMN. Indeed, for IPMN with obvious malignant transformation, an hemi-pancreatectomy with lymphadenectomy is indicated, thus limiting discussion about the extent of pancreatic resection.

There is no consensual agreement about the management of the residual pancreas according the pathological analysis of the pancreatic margin at FS. It well known that, in surgical series, the rate of invasive carcinoma in patients with IPMN involving the main duct is high, ranging from 45% to 57% vs 6% to 37% for branch-ducts IPMN[9-15]. Furthermore, the risk of malignant transformation also greatly depends on the topography (i.e. branch ducts versus main duct) of the lesions: indeed, the 5-year risk of malignant transformation is 63% and 15% in main duct and branch ducts lesions respectively[16]. As a matter of fact, branch-duct IPMN lesions are presently managed nonoperatively if asymptomatic and without morphological signs suggestive of malignant transformation[16-21]. Then, according to the above data, in our center we analyze separately the lesions in main-duct and branch ducts[8]. We treat even a minimal lesion involving the main duct by additional resection[8]. Conversely, we tolerate residual mild dysplasia limited to branch ducts since it can be hypothesized that branch-duct IPMN-adenoma which is left in place carries a very delayed risk of recurrent evolutive disease[16-19]. So, our standard option is to extend the pancreatectomy if FS reveals: (1) at least IPMN adenoma on the main duct; or (2) at least borderline IPMN on branch ducts; or (3) invasive carcinoma.

However, the decision to extend or not pancreatectomy does not exclusively depend on the FS result but also on age, general condition and presumed stage of the disease (malignant or benign). As a first example, the value of total pancreatectomy for invasive IPMN when the transection margin is involved by dysplasia is debated: some authors advocate extending pancreatectomy until a disease-free margin on the main pancreatic duct is obtained[22] but most others, considering that long-term prognosis is affected mainly by the invasive component, do not recommend extending the pancreatectomy in this setting provided there is no invasive disease on the margin[10,23-25]. As a second example, leaving IPMN adenoma in main duct may be acceptable in a high-risk patient while presence of high-grade dysplasia should in most cases lead to accept an additional resection.

Technical possibilities of extending the pancreatic resection greatly vary according to the different types of resection. Furthermore, consequences of pancreatic resections also vary between the different procedures and according to the size of the residual pancreas.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy: After PD, the risk of de novo diabetes after PD is low, ranging from 0 to 7%[26-28]. Some patients keep a normal endocrine function with a 5 to 6 cm pancreatic remnant limited to the tail. Lastly, since IPMN usually predominates in the right pancreas or is limited to this side[6,8,9], it is possible in most cases to perform a complete resection.

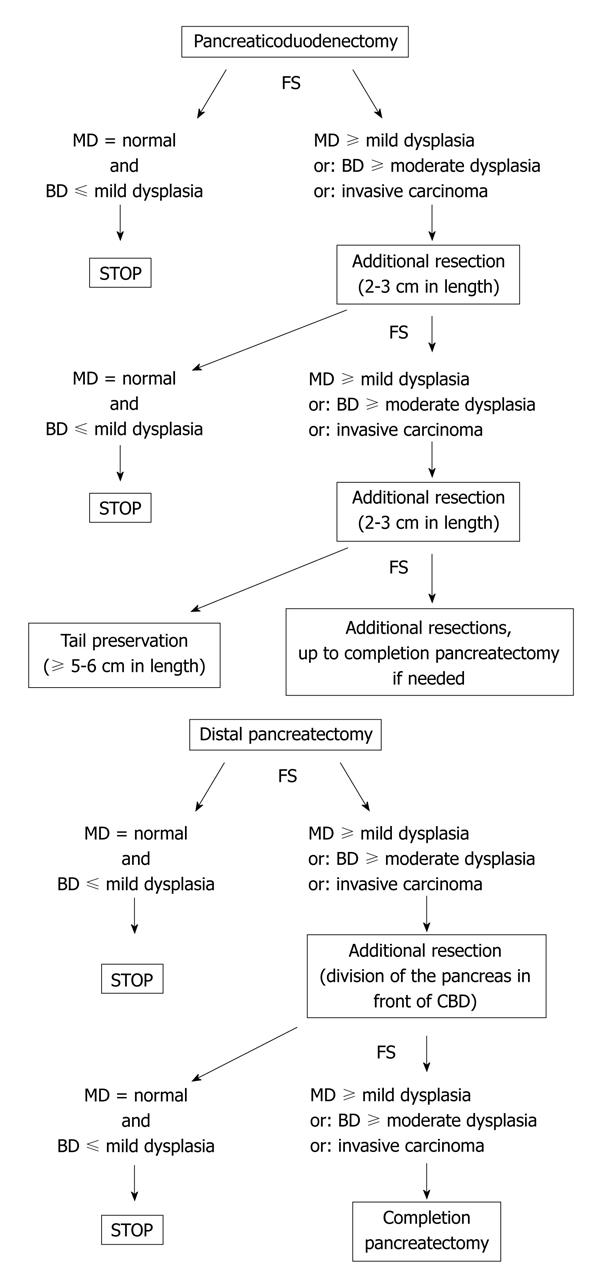

According to these data, when the FS result on the pancreatic neck indicates to extend the resection, we recommend to remove a 2 to 3 cm additional pancreatic segment (progressively separated from the splenic vessels with ligature of their collaterals) and to check to the new transection margin by additional FS; if needed, a third or even fourth additional pancreatic resection can be performed (Figure 5). The pancreatic tail can be preserved and anastomosed to the digestive track if its length is at least 5 to 6 cm to ensure a significant endocrine function[29,30]. If the residual is less than 5 cm, three options are possible: (1) to try to perform an anastomosis which can be technically difficult with an uncertain long-term benefit; (2) to suture the margin and leave in place the remnant tail which can lead to a prolonged pancreatic fistula; and (3) to remove it, thus avoiding postoperative pancreatic complications but leading to a pancreatoprive diabetes. The former option can be chosen if the patient is young and there is no suspicion of residual disease.

It must be underlined that the attitude of successive resections with iterative FS during PD can limit the risk of surgically induced diabetes and, at the most, the risk of total pancreatectomy while suppressing all “risky” epithelium. As a matter of fact, in our previous series of 90 PD with FS, at least two margins (from 2 to 4) were examined by FS in 37% of procedures. Also, of the 127 patients in whom a partial pancreatectomy with FS was planned, only 9 (7%) ultimately underwent total pancreatectomy[8].

Distal pancreatectomy: In selected cases, a very short resection (limited to the tail) can be performed. In this case, it is easy to extend the resection if indicated by the FS result. In contrast, if the whole distal pancreas has been removed with division of the neck, the possibilities of extending the pancreatectomy are limited. The head-neck junction can be resected with division of the pancreas at the anterior edge of the common bile duct (or slightly on its left) provided the gastroduodenal artery has been mobilized with division of its pancreatic collaterals or even resected. This creates a wider transsection margin with a likely higher risk of fistula but with another possibility of FS (Figure 5). If this latter margin is involved by IPMN lesions indicating an additional resection, this usually leads to complete the pancreatectomy by means of a PD provided the operative risk is low. Taking into account that IPMN lesions rarely predominate on the distal pancreas[6,8,9], the risk of completing pancreatectomy during distal pancreatectomy is low but may exist. For this reason, the patient should be aware of this possibility.

Medial pancreatectomy: The management of both margins analysis during medial pancreatectomy associates the analysis of each margin as performed for PD and DP[8,30]. However, especially if there is some suspicion of segmental involvement of the main duct, FS results on both margins should be known before any additional resection is started. As an example, finding mild dysplasia on the main duct of the left margin should not indicate necessarily to extend resection to the left if high-grade dysplasia is present on the right-margin which should imply to resect the pancreatic head.

Enucleation: In this indication, FS is performed in order to: (1) to check, as for other procedures, if the resection is complete. For this purpose, the communicating duct is analyzed and is considered as a branch-duct with a cut-off tolerating only mild dysplasia as described above. Since the communicating dust is usually small in diameter (less than 1 mm), the surgeon must mark it with a stitch or give it separately; and (2) to exclude invasive malignancy which requires an oncological resection[31]. For this purpose, the cyst is opened by the pathologist who select a suspect area if present i.e. papillae, mural nodule or wall thickening. Since there is no strict correlation between gross aspect and histology in case of microinfiltrative adenocarcinoma, we recommend to routinely perform this analysis. Moreover, the histological grading of dysplasia in the cyst can help to analyze the communicating duct which is always limited in size.

Total pancreatectomy: In some patients, a total pancreatectomy is planned. However, it can be interesting to perform it as a two-step procedure event if it is more complicated. Indeed, passive dilatation associated with IPMN can mimic diffuse main duct involvement. Passive dilatation can be located upstream from a stenosis (usually due to invasive carcinoma) but also downstream from a mucin-producing lesion resulting in ductal dilatation towards the papilla.

There are very few series that report the value of FS during pancreatectomy for IPMN. In the series published by Falconi et al[6] in 2001, the margin was analyzed by frozen section without precision on the subtype of duct involved (i.e. main or branch duct); they considered as positive the margins harbouring high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma. Fifty-one patients were included and definitive examination confirmed the result of FS in 100% of cases. Interestingly, they showed that the 4 patients who subsequently underwent reoperation for recurrence had deepithelialized duct at the margin of the first operation. Another experience published in 2007 and including 27 FS of pancreatic margins reported a predictive positive and negative value of 88% and 47% respectively[7].

In our series of 127 consecutive patients who underwent pancreatic resection for IPMN at our institution, the accuracy of FS for detection of “significant” lesions as defined above was 94% and the routine use of FS led to modify the planned resection in 30% of the patients[8]. This rate is comparable to the 23% rate of modification of the planned operation reported by Gigot et al[5]. Of our patients who had additional resection because of significant lesions at the first FS, 95% had IPMN lesions on the second resection specimen which demonstrated that the analysis of the margin is efficient to guide the extent of pancreatectomy in this disease.

Moreover, we highlighted in our study that the rate of “significant” lesions was greater in cases of IPMN involving the main duct (39% vs 15% in case of branch-duct IPMN, P < 0.01). The rate of significant lesions on the first analyzed FS was almost the same as if it was a PD or a left pancreatectomy (28%) but rose to 50% in case of planned medial pancreatectomy[8]. As reported by Wada et al[23], we found an eroded main-duct epithelium in 8% of cases. We then suggest this finding should routinely lead to an additional resection since it seems to be associated with recurrence in the pancreatic remnant.

During enucleation of branch-duct IPMN, accuracy of FS on the dilated duct and the communicating seems equivalent to that observed with analysis of a full pancreatic margin in our experience[31].

In addition to eroded epithelium on the main duct that we discussed above, the presence of severe inflammation may wrongly mimic dysplasia by increasing cellular atypias. In contrast, duct dilatation harboring hyperplastic reactive epithelial changes secondary to obstruction or chronic pancreatitis may be wrongly interpreted as IPMN[2,24,32]. Recognition of these ductal lesions may avoid pancreatectomies with excessive extent.

The main limit of using FS to adapt extent of resection is the existence of discontinuous (“skip”) lesions. Rate of discontinuous lesions ranges from 6% to 19% in surgical series[25,33,34]. However, it is well known that the degrees of dysplasia can vary in the same patient and it is likely that some tumors were classified as discontinuous even in case of areas of mild dysplasia separating areas with more severe lesions.

The main clinical consequence of skip lesions is the possibility of recurrence after partial pancreatectomy with normal transection margin[9,11,24]. Recurrence after resection for invasive IPMN is mainly due to the invasive component. Conversely, the rate of recurrence after partial pancreatectomy for non invasive IPMN is low, not exceeding 8% of cases[7,9,11,24]. In this setting, the rate of local recurrence seems higher when the margin is involved by IPMN lesions than when disease-free; in the study of White et al[7] this rate was 17% (4/23) and 3% (1/32) respectively.

To detect “skip” lesions, the only reported techniques are cytology of pancreatic juice harvested in the remnant in addition to FS and intraoperative wirsungoscopy with staged biopsies. In the study of Eguchi et al[34], 8 discontinuous IPMN were proven after analysis of the entire segments of resected pancreas at definitive histology. Among these eight, 5/8 (i.e. 5/43 = 12% of the whole series) had been detected by the only result of intraoperative cytology. Intraoperative wirsungoscopy with staged biopsies has only been reported by a few groups[5,35]; probably because this technique is only suitable for detection of main duct lesions provided the main duct is dilated.

In conclusion, FS is a necessary tool for the surgical management of IPMN and should be used routinely. Although the optimal cut-off leading to extend pancreatectomy is not consensual, FS is helpful to evaluate the completeness of resection and also to check if ductal dilatation is active or passive, in order to avoid an excessive pancreatic resection. Separate main duct and branch duct analysis seems convenient, due to the difference in natural history of the disease. To be accurate, FS needs an optimal technique from the surgeon and the pathologist. The decision not to extend resection or to perform an additional partial pancreatic resection must be taken after a multidisciplinary discussion since it does not exclusively depend on the FS result but also on age, general condition and the expected prognosis after resection.

| 1. | Longnecker DS, Adler G, Hruban RH, Klöppel G. Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. WHO classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 237–240. |

| 2. | Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Compton C, Fukushima N, Furukawa T. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:977-987. |

| 3. | Adsay NV, Merati K, Basturk O, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Levi E, Cheng JD, Sarkar FH, Hruban RH, Klimstra DS. Pathologically and biologically distinct types of epithelium in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: delineation of an "intestinal" pathway of carcinogenesis in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:839-848. |

| 4. | Paye F, Sauvanet A, Terris B, Ponsot P, Vilgrain V, Hammel P, Bernades P, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: pancreatic resections guided by preoperative morphological assessment and intraoperative frozen section examination. Surgery. 2000;127:536-544. |

| 5. | Gigot JF, Deprez P, Sempoux C, Descamps C, Metairie S, Glineur D, Gianello P. Surgical management of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: the role of routine frozen section of the surgical margin, intraoperative endoscopic staged biopsies of the Wirsung duct, and pancreaticogastric anastomosis. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1256-1262. |

| 6. | Falconi M, Salvia R, Bassi C, Zamboni G, Talamini G, Pederzoli P. Clinicopathological features and treatment of intraductal papillary mucinous tumour of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2001;88:376-381. |

| 7. | White R, D'Angelica M, Katabi N, Tang L, Klimstra D, Fong Y, Brennan M, Allen P. Fate of the remnant pancreas after resection of noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:987-993; discussion 993-995. |

| 8. | Couvelard A, Sauvanet A, Kianmanesh R, Hammel P, Colnot N, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, Bedossa P, Belghiti J. Frozen sectioning of the pancreatic cut surface during resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas is useful and reliable: a prospective evaluation. Ann Surg. 2005;242:774-778, discussion 778-780. |

| 9. | Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Hruban RH, Fukushima N, Campbell KA, Lillemoe KD. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. Ann Surg. 2004;239:788-797; discussion 797-799. |

| 10. | Sugiyama M, Izumisato Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Predictive factors for malignancy in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumours of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1244-1249. |

| 11. | Salvia R, Fernández-del Castillo C, Bassi C, Thayer SP, Falconi M, Mantovani W, Pederzoli P, Warshaw AL. Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of malignancy and long-term survival following resection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:678-685; discussion 685-687. |

| 12. | Bernard P, Scoazec JY, Joubert M, Kahn X, Le Borgne J, Berger F, Partensky C. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: predictive criteria of malignancy according to pathological examination of 53 cases. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1274-1278. |

| 13. | Sugiyama M, Abe N, Tokuhara M, Masaki T, Mori T, Takahara T, Hachiya J, Atomi Y. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for postoperative follow-up of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 2003;185:251-255. |

| 14. | Imaizumi T, Hatori T, Harada N, Fukuda A, Takasaki K, Hanyu F. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas; resection and cancer prevention. Am J Surg. 2007;194:S95-S99. |

| 15. | Nagai K, Doi R, Kida A, Kami K, Kawaguchi Y, Ito T, Sakurai T, Uemoto S. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term follow-up after resection. World J Surg. 2008;32:271-278; discussion 279-280. |

| 16. | Lévy P, Jouannaud V, O'Toole D, Couvelard A, Vullierme MP, Palazzo L, Aubert A, Ponsot P, Sauvanet A, Maire F. Natural history of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: actuarial risk of malignancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:460-468. |

| 17. | Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, Matsuno S. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32. |

| 18. | Rautou PE, Lévy P, Vullierme MP, O'Toole D, Couvelard A, Cazals-Hatem D, Palazzo L, Aubert A, Sauvanet A, Hammel P. Morphologic changes in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a midterm follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:807-814. |

| 19. | Pelaez-Luna M, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Takahashi N, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Vege SS. Do consensus indications for resection in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm predict malignancy? A study of 147 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1759-1764. |

| 20. | Schmidt CM, White PB, Waters JA, Yiannoutsos CT, Cummings OW, Baker M, Howard TJ, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, DeWitt JM. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: predictors of malignant and invasive pathology. Ann Surg. 2007;246:644-651; discussion 651-654. |

| 21. | Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Itoh A, Ishigami M, Katano Y, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, Goto H. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: differentiation of malignant and benign tumors by endoscopic ultrasound findings of mural nodules. Ann Surg. 2009;249:628-634. |

| 22. | Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Oda K, Nishio H, Ebata T, Abe T, Igami T, Nimura Y. Clinicopathologic features of re-resected cases of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). Surgery. 2007;142:136-142. |

| 23. | Wada K, Kozarek RA, Traverso LW. Outcomes following resection of invasive and noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 2005;189:632-636; discussion 637. |

| 24. | Chari ST, Yadav D, Smyrk TC, DiMagno EP, Miller LJ, Raimondo M, Clain JE, Norton IA, Pearson RK, Petersen BT. Study of recurrence after surgical resection of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1500-1507. |

| 25. | Raut CP, Cleary KR, Staerkel GA, Abbruzzese JL, Wolff RA, Lee JH, Vauthey JN, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: effect of invasion and pancreatic margin status on recurrence and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:582-594. |

| 26. | Lemaire E, O'Toole D, Sauvanet A, Hammel P, Belghiti J, Ruszniewski P. Functional and morphological changes in the pancreatic remnant following pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastric anastomosis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:434-438. |

| 27. | Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, Chijiiwa K, Nagakawa T, Imamura M, Takada T. Early and late complications of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in Japan 1998. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:303-311. |

| 28. | Ishikawa O, Ohigashi H, Eguchi H, Yokoyama S, Yamada T, Takachi K, Miyashiro I, Murata K, Doki Y, Sasaki Y. Long-term follow-up of glucose tolerance function after pancreaticoduodenectomy: comparison between pancreaticogastrostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy. Surgery. 2004;136:617-623. |

| 29. | Ihse I, Anderson H, Andrén-Sandberg . Total pancreatectomy for cancer of the pancreas: is it appropriate? World J Surg. 1996;20:288-293; discussion 294. |

| 30. | Adham M, Giunippero A, Hervieu V, Courbière M, Partensky C. Central pancreatectomy: single-center experience of 50 cases. Arch Surg. 2008;143:175-180; discussion 180-181. |

| 31. | Blanc B, Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Pessaux P, Dokmak S, Vullierme MP, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J. [Limited pancreatic resections for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm]. J Chir (Paris). 2008;145:568-578. |

| 32. | Tanaka M. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: diagnosis and treatment. Pancreas. 2004;28:282-288. |

| 33. | D'Angelica M, Brennan MF, Suriawinata AA, Klimstra D, Conlon KC. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of clinicopathologic features and outcome. Ann Surg. 2004;239:400-408. |

| 34. | Eguchi H, Ishikawa O, Ohigashi H, Sasaki Y, Yamada T, Nakaizumi A, Uehara H, Takenaka A, Kasugai T, Imaoka S. Role of intraoperative cytology combined with histology in detecting continuous and skip type intraductal cancer existence for intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer. 2006;107:2567-2575. |

Peer reviewer: Gregory Peter Sergeant, MD, Department of General Surgery, University Hospital Leuven, Herestraat 49, Leuven B-3000, Belgium

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yang C