Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.115444

Revised: November 5, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 97 Days and 2.2 Hours

Interleukin-8 (IL-8), a pro-inflammatory chemokine, is implicated in angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. However, its diagnostic and prognostic signifi

To evaluate the diagnostic utility of serum IL-8 in patients with newly diagnosed colon adenocarcinoma.

In this prospective case-control study, 44 treatment-naïve patients with colon adenocarcinoma and 44 age-matched healthy controls were enrolled. Preoperative serum IL-8 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Statistical analyses included univariate and multivariate models, odds ratios, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Serum IL-8 levels were significantly higher in patients than in controls (P = 0.005). ROC curve analysis yielded an area under the curve of 0.68, with both sensitivity and specificity of 63.6% at a cut-off value of 42.3 ng/L. Multivariate analysis confirmed IL-8 as an independent predictor (odds ratio = 1.050), with each 1 ng/L increase conferring a 5% higher risk. No significant associations were observed with tumor stage, location, or histopathological features.

IL-8 may serve as a diagnostic biomarker in colon adenocarcinoma, and its potential prognostic role warrants validation in larger, multicenter cohorts.

Core Tip: This prospective study demonstrates that serum interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels were significantly elevated in colon adenocarcinoma patients. Although diagnostic accuracy was moderate (area under the curve = 0.68), IL-8 remained an independent predictor. Prior evidence links IL-8 to survival and treatment response, suggesting diagnostic and prognostic utility. Larger multicenter studies are warranted to confirm and explore therapeutic implications.

- Citation: Güneş G, Fırat Oğuz E, Kayılıoğlu I, Dinç T. Diagnostic value of interleukin-8 in colon cancer: Prospective, case-control study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 115444

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/115444.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.115444

Colon cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, ranking third among all malignancies in both incidence and mortality[1]. Its high mortality rate is largely attributed to late-stage diagnosis when curative treatment options are limited. Early detection plays an important role in improving survival rates, emphasizing the need for reliable biomarkers that can aid in both early diagnosis and monitoring disease progression[2]. In recent years, there has been growing interest in the role of inflammation in cancer, with circulating inflammatory cytokines being recognized as promising prognostic biomarkers. These cytokines may provide valuable insights into tumor biology and patient outcomes, making them key targets in cancer research[2].

Interleukin-8 (IL-8), also known as CXCL-8, is a member of the CXC chemokine family and plays a pivotal role in immune response regulation by mediating the recruitment and activation of neutrophils and other immune cells[3]. Apart from its role in inflammation, IL-8 is also involved in cancer development, participating in processes such as angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and metastasis[4,5]. Elevated levels of IL-8 have been found in various cancers, including gastric, breast, and lung cancers, where its overexpression is associated with poor prognosis and increased metastatic potential[4,5]. In gastrointestinal malignancies, IL-8 has emerged as a key mediator of the tumor microenvironment, promoting angiogenesis, immune evasion, and metastatic spread[6,7]. In colorectal cancer specifically, IL-8 has been implicated in tumor progression and metastasis, but its diagnostic utility as a non-invasive serum biomarker remains unclear, with conflicting findings across different populations[8,9]. This gap in knowledge underscores the need for prospective studies evaluating IL-8’s potential in early detection and risk stratification.

We hypothesized that serum IL-8 levels are significantly higher in patients with colon adenocarcinoma than in healthy controls, and that IL-8 may serve as a potential biomarker for early detection.

We conducted a prospective, single-center, case-control study including patients newly diagnosed with colon adenocarcinoma who presented to the General Surgery and Emergency Surgery Departments of our tertiary institution between September and December 2021. The study protocol was designed in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of University of Health Sciences (No. E1-21-1845). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

The primary endpoint of the study was to compare preoperative serum IL-8 levels between patients with colon adenocarcinoma and age-matched healthy controls. Secondary endpoints included: (1) To assess the diagnostic accuracy of IL-8 levels using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis; (2) To calculate the odds ratio for colon adenocarcinoma per unit increase in IL-8 concentration; and (3) To examine the relationship between IL-8 levels and clinicopathological features such as tumor location, stage, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion.

Adult patients aged 18-85 years with newly diagnosed, treatment-naive colon adenocarcinoma who presented to the General Surgery and Emergency Surgery Departments of our tertiary institution between September 2021 and December 2021 were consecutively enrolled. Based on an a priori power analysis (effect size = 0.6, α = 0.05, power = 0.80), a minimum of 44 patients in both the study and control groups was targeted, as this sample size was determined to be sufficient to detect a statistically significant difference in serum IL-8 levels between groups. Patients were excluded if they had rectal cancer, recurrent disease, prior neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, histopathological findings other than adenocarcinoma, or severe comorbid conditions that would preclude participation. The control group consisted of adult volunteers without a history of malignancy who were admitted for benign, elective surgical procedures and were matched with the study group by age. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

For all participants, demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded, including age, sex, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, thyroid disorders, and kidney disease), clinical presentation (elective vs emergency admission), and routine laboratory data [complete blood count, biochemistry, liver enzymes, creatinine, C-reactive protein (CRP), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)]. In the study group, tumor-related variables such as tumor location (right colon, left colon, or synchronous), tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control classification[10], lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and microsatellite instability status were documented.

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected preoperatively from all patients specifically for IL-8 measurement. All data were entered into a dedicated database and checked for accuracy by two independent investigators.

The biochemical analysis of the study was conducted at the Central Biochemistry Laboratory of our institution. Venous blood samples were collected in serum tubes with gel and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma tubes. After collection, the serum samples were allowed to clot for 20 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 1300 g for 10 minutes. The serum samples were then divided into aliquots and stored at -80 °C until further analysis. IL-8 levels were measured using a commercially available human IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (USCN, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) with a detection range of 15.6-1000 ng/L, sensitivity of 5.9 ng/L, and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of < 8% and < 10%, respectively. Complete blood counts were performed using an ADVIA 2120 Hematology Analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Germany), and CEA levels were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay technique with the Atellica Solutions (Siemens Healthineers, Germany) autoanalyzer.

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0. All statistical methods were reviewed by a biomedical statistician. The normality of numerical data was assessed through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables were presented as n (%), while continuous variables were expressed as means with SDs. Depending on the distribution, either the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for univariate analysis, while the χ2 test was used for comparing categorical variables. Variables with a P value < 0.20 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Additionally, a ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of IL-8 as a biomarker. Statistical significance was determined at a 95% confidence level, and P values below 0.05 were considered significant.

A total of 44 patients with newly diagnosed, untreated colon adenocarcinoma formed the study group, while the control group included 44 volunteers without a malignancy history. All participants were recruited consecutively between September 2021 and December 2021, and enrollment was closed once the predetermined sample size was reached. All elective patients were diagnosed via colonoscopy, whereas emergency cases presenting with tumor ileus or perforation were diagnosed using radiological imaging. The mean age of the study group was 62.98 (± 14.58) years, while the control group had a mean age of 63.89 (± 13.71) years. The proportion of males in the study group was 56.8% (n = 25), compared to 45.5% (n = 20) in the control group (P = 0.286). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, gender, or comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases, thyroid disorders, or kidney diseases.

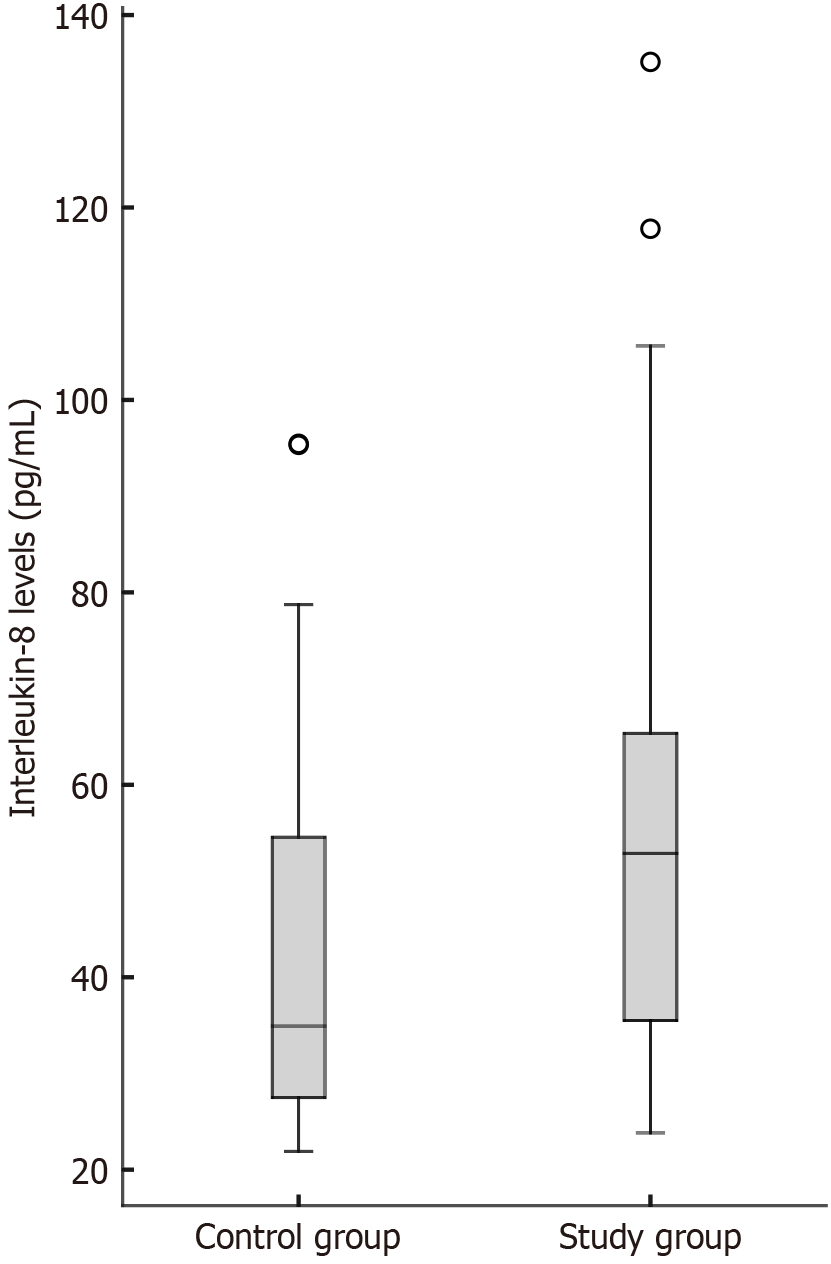

Serum IL-8 levels, the primary outcome of the study, were significantly higher in the colon adenocarcinoma group compared with healthy controls (P = 0.005). Comparison of comorbidities and laboratory results between groups in univariate analysis is shown in Table 1, and the distribution of IL-8 levels within the groups is presented in Figure 1.

| Study group | Control group | P value | |

| CEA (μg/L), median (IQR) | 1.80 (1.00-5.05) | 1.05 (0.65-1.44) | < 0.0011 |

| IL-8 (ng/L), median (IQR) | 53.88 (35.25-65.53) | 34.93 (27.33-54.81) | 0.0051 |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 0.1 (0.10-0.50) | 0.2 (0.20-0.60) | 0.1391 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.35 ± 2.37 | 12.41 ± 2.14 | 0.903 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 9.49 ± 3.85 | 9.72 ± 4.01 | 0.838 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 317.45 ± 106.53 | 270.86 ± 77.24 | 0.0211 |

| AST (IU/L), median (IQR) | 20 (19-29) | 20 (16-31) | 0.613 |

| ALT (IU/L), median (IQR) | 18 (14-29) | 24 (18-34) | 0.0191 |

| Albumin (g/L), median (IQR) | 41.0 (34.5-44.0) | 40.0 (33.5-45.0) | 0.930 |

| Urea (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 33 (25-48) | 34 (26-45) | 0.776 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.88 (0.73-1.08) | 0.76 (0.63-0.96) | 0.0321 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.02 ± 0.51 | 4.09 ± 0.49 | 0.536 |

| Hypertension (%) | 22.7 | 43.2 | 0.0411 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 11.4 | 22.7 | 0.1561 |

| COPD (%) | 9.1 | 2.3 | 0.360 |

ROC curve analysis demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.68 (95% confidence interval: 0.56-0.79). A cutoff value of 42.3 ng/L resulted in both sensitivity and specificity of 63.6%. The odds ratio for IL-8 was 1.050, indicating a 5% increase in the odds of colon adenocarcinoma for each 1 ng/L increment in IL-8. Results of the multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 2, which identified IL-8, CEA, and platelet count as independent predictors of colon adenocarcinoma.

Regarding tumor location, 10 patients (22.7%) had tumors in the right colon, 32 patients (72.7%) in the left colon, and two patients had synchronous tumors, one in each location. No significant differences in IL-8 levels were observed according to tumor location. Similarly, IL-8 levels did not differ significantly between patients presenting electively and those presenting as emergencies.

Further analysis revealed no significant associations between IL-8 levels and T stage, N stage, overall disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, or microsatellite instability (Table 3). There were no adverse events associated with blood sampling or biochemical analyses.

| Variable | Category | Number | IL-8 (pg/mL) | P value1 |

| Tumor location, median (IQR) | Right colon | 10 | 53.20 (37.38-66.63) | |

| Left colon | 31 | 44.61 (35.59-60.83) | ||

| Synchronous | 3 | 77.65 (41.10-91.40) | 0.2223 | |

| T stage, median (IQR) | T2 | 3 | 44.61 (43.62-60.79) | |

| T3 | 27 | 52.66 (35.91-60.06) | ||

| T4 | 14 | 56.56 (30.80-66.45) | 0.9124 | |

| N stage, median (IQR) | N0 | 24 | 45.61 (35.66-68.13) | |

| N1 | 15 | 53.29 (35.91-63.14) | ||

| N2 | 5 | 56.85 (34.76-59.72) | 0.9988 | |

| Overall stage, median (IQR) | Stage 1 | 4 | 46.60 (38.68-79.07) | |

| Stage 2 | 21 | 53.10 (33.62-62.79) | ||

| Stage 3 | 13 | 46.60 (36.72-76.97) | ||

| Stage 4 | 6 | 53.10 (34.12-62.45) | 0.9585 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion, median (IQR) | Absent | 13 | 46.60 (38.68-79.07) | |

| Present | 31 | 53.10 (33.62-62.79) | 0.6433 | |

| Perineural invasion, median (IQR) | Absent | 21 | 46.60 (36.72-76.97) | |

| Present | 23 | 53.10 (34.12-62.45) | 0.7870 | |

| Microsatellite instability, median (IQR) | MSS/MSI-L | 40 | 53.20 (35.50-66.12) | |

| MSI-H | 4 | 44.28 (39.48-47.58) | 0.3373 | |

| Mode of presentation, median (IQR) | Elective | 29 | 53.10 (36.72-65.87) | |

| Emergency | 14 | 50.38 (31.69-63.10) | 0.5685 |

The role of inflammatory cytokines in tumorigenesis has received growing attention in recent years, reflecting a broader trend toward identifying circulating biomarkers that may assist in the early detection and prognostic assessment of gastrointestinal malignancies[2,4]. Among these, IL-8 is a chemokine involved in tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastatic spread[5,7]. Previous studies have reported elevated IL-8 levels in gastric, breast, and lung cancers, linking its overexpression to more aggressive disease biology and poorer survival outcomes[4,7]. In colorectal cancer, however, the diagnostic utility of IL-8 remains less clearly defined, with findings varying across different populations and study designs.

Our findings demonstrate that serum IL-8 can distinguish colon adenocarcinoma patients from healthy controls with moderate diagnostic accuracy. While the observed AUC of 0.68 falls short of the threshold typically required for stand-alone screening biomarkers (AUC ≥ 0.80), it is important to contextualize this performance within the broader landscape of colorectal cancer biomarkers. For comparison, CEA, the most widely used biomarker in clinical practice, exhibits similar limitations in early-stage disease detection, with reported sensitivities ranging from 30% to 50% for localized tumors[11]. The moderate discriminatory capacity of IL-8 observed in our study suggests that, rather than serving as a replacement for existing markers, IL-8 may provide complementary diagnostic value when integrated into multi-marker panels[12].

The independent predictive value of IL-8 in multivariate analysis, even after adjusting for CEA and other confounders, underscores its potential biological relevance. The odds ratio of 1.050 per ng/L increment, while modest, indicates a dose-response relationship that may reflect the underlying inflammatory and angiogenic processes driving tumor development[4,7]. This incremental risk assessment could be particularly valuable in risk stratification models, where combining multiple biomarkers with modest individual performance can yield clinically meaningful improvements in diagnostic accuracy[12]. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that IL-8, when combined with CEA and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), significantly enhances diagnostic performance compared to any single marker alone, achieving AUC values exceeding 0.85 in some cohorts[12,13].

The diagnostic performance of IL-8 observed in our study is notably lower than that reported in several prior investigations. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Xia et al[8], which pooled data from multiple studies, reported substantially higher diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.92, sensitivity = 70%, specificity = 91%). Several methodological and population related factors may account for this discrepancy. First, the meta-analysis included studies with heterogeneous patient populations, some of which comprised advanced stage or metastatic disease, where IL-8 levels are typically more markedly elevated due to greater tumor burden and systemic inflammation[8,9]. In contrast, our cohort consisted predominantly of early to intermediate stage disease (stage I-III: 86.4%), which may explain the more modest elevation in IL-8 levels and the correspondingly lower diagnostic accuracy.

Second, variations in ELISA methodology, including differences in antibody specificity, sample handling protocols, and detection thresholds, can significantly influence measured IL-8 concentrations and contribute to inter-study variability[8]. Third, ethnic and geographic differences in baseline inflammatory profiles may affect the discriminatory capacity of IL-8. Our cohort, derived from a Turkish population, may exhibit distinct inflammatory characteristics compared to the predominantly Asian and European cohorts included in prior meta-analyses[8].

Despite these differences, our findings align with several individual studies reporting diagnostic performance for IL-8. The meta-analysis by Jin et al[14] demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of IL-8 levels was comparable to CEA. Similarly, Björkman et al[15] found that IL-8 alone had modest diagnostic utility but significantly improved prognostic stratification when combined with CEA in a multi-marker model[15]. These observations reinforce the notion that IL-8 is best utilized as part of a comprehensive biomarker panel rather than as a standalone diagnostic tool[12,13].

Our subgroup analyses, detailed in Table 3, revealed no statistically significant associations between serum IL-8 levels and key clinicopathological features, including tumor location, TNM stage, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, or microsatellite instability status. Although IL-8 levels showed a trend toward higher values in patients with synchronous tumors compared to those with right-sided or left-sided tumors, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, no significant differences were observed across T stages, N stages, or overall disease stages. These negative findings contrast with several reports that linked elevated IL-8 expression to advanced tumor stages and metastatic disease. For instance, Rubie et al[9] showed that increased IL-8 expression correlated with distant metastases, while Ueda et al[16] and Pączek et al[17] suggested that higher circulating IL-8 levels might reflect tumor aggressiveness and worse prognosis in colorectal cancer. Several factors may explain the absence of such associations in our cohort. To begin with, the relatively small sample size, particularly in certain subgroups (e.g., synchronous tumors, n = 3; stage I,

From a clinical perspective, IL-8 offers several potential advantages over traditional tumor markers such as CEA and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, particularly in the context of early detection and risk stratification. First, IL-8 reflects active inflammatory and angiogenic processes within the tumor microenvironment[4,7], providing complementary biological information that is distinct from the epithelial cell turnover measured by CEA. This mechanistic difference suggests that IL-8 may be particularly useful in detecting tumors that are CEA-negative or exhibit low CEA expression, which occurs in approximately 30%-40% of colorectal cancers[11]. Second, IL-8 can be measured using standard ELISA techniques with high reproducibility and relatively low cost, making it feasible for implementation in routine clinical practice[8]. Third, unlike imaging-based screening modalities such as colonoscopy, IL-8 measurement is non-invasive and can be performed on peripheral blood samples, facilitating serial monitoring and longitudinal risk assessment[8].

The integration of IL-8 into multi-marker diagnostic panels represents a promising strategy for improving early detection rates. Several studies have demonstrated that combining IL-8 with CEA, VEGF, and other biomarkers significantly enhances diagnostic accuracy compared to any single marker alone. For example, Bünger et al[13] reported that a panel comprising IL-8, CEA, and VEGF achieved an AUC of 0.87 for detecting pancreatic cancer, substantially higher than CEA alone (AUC = 0.65)[13]. Similarly, Mahboob et al[12] developed a multiplexed immunoassay incor

Beyond diagnosis, IL-8 holds significant promise as both a prognostic and predictive biomarker in colorectal cancer. From a prognostic perspective, accumulating evidence demonstrates that elevated IL-8 levels are associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Czajka-Francuz et al[18] showed that preoperative serum IL-8 levels correlated with shorter overall survival and disease-free survival in colorectal cancer patients, suggesting that IL-8 reflects aggressive disease biology beyond mere tumor presence. Similarly, Park et al[19] reported that higher systemic IL-8 concentrations were indepen

Looking forward, IL-8 may also represent a therapeutic target in its own right. Several IL-8 or CXCR2-targeted agents are currently in preclinical and early clinical development, with the goal of disrupting the pro-tumorigenic signaling mediated by the IL-8/CXCR2 axis[23]. By blocking IL-8 signaling, these agents aim to inhibit angiogenesis, reduce immunosuppression, and enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. While these approaches remain investigational, they underscore the multifaceted clinical relevance of IL-8 in colorectal cancer management[23].

Our study possesses several methodological strengths that enhance the validity and clinical relevance of our findings. Initially, the prospective design minimizes selection bias and ensures that IL-8 measurements were obtained prior to any therapeutic intervention, providing an unbiased assessment of its diagnostic potential in treatment-naive patients. This is particularly important given that chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical stress can all influence circulating cytokine levels, potentially confounding retrospective analyses[2,4]. Additionally, the careful demographic matching between the patient and control groups, particularly with respect to age, reduces the likelihood that observed differences in IL-8 levels are attributable to age related inflammatory changes rather than tumor specific processes[2]. Moreover, the inclusion of comprehensive clinicopathological data, including TNM staging, histopathological features, and microsatellite instability status, enabled detailed subgroup analyses that provide insights into the biological heterogeneity of IL-8 expression. Lastly, the concurrent measurement of established biomarkers such as CEA and CRP allowed for direct comparison and assessment of IL-8’s incremental diagnostic value, contextualizing its performance within the existing diagnostic landscape[8,12,13].

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size may have reduced statistical power, particularly in subgroup analyses such as tumor location, where only three patients had synchronous tumors. This limitation might also explain the absence of significant associations between IL-8 levels and clinicopathological factors such as TNM stage or lymphovascular invasion, which have been reported in larger cohorts[9,15,16]. Larger, multi-center studies are needed to validate these findings and assess interactions between IL-8 and clinical variables.

Second, the single center design limits generalizability, as geographic, ethnic, and dietary factors can influence inflammatory profiles and diagnostic thresholds[8]. Multi-center studies across diverse populations are warranted to confirm the diagnostic performance of IL-8.

Third, the lack of long-term follow-up precluded assessment of the prognostic value of IL-8 for recurrence, metastasis, or survival. As discussed earlier, prior research has demonstrated the prognostic significance of IL-8 in colorectal cancer[18-20]. Future studies with longitudinal data are needed to determine whether IL-8 dynamics predict outcomes.

Lastly, although groups were age-matched, residual confounding due to comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes cannot be entirely excluded[2]. The absence of an external validation cohort further limits robustness; validation in independent datasets is essential to confirm clinical applicability[8].

In conclusion, our prospective study demonstrates that serum IL-8 levels are significantly elevated in patients with colon adenocarcinoma and can distinguish cancer patients from healthy controls with moderate diagnostic accuracy. While IL-8 alone does not achieve the diagnostic performance required for standalone screening, its independent predictive value and distinct biological relevance suggest that it may provide complementary information when integrated into multi-marker panels[8,12,13]. The absence of significant associations with clinicopathological features in our cohort likely reflects limited statistical power and highlights the need for larger, multi-center validation studies. From a translational perspective, IL-8 represents a promising biomarker for risk stratification, treatment response monitoring, and therapeutic targeting in colorectal cancer[21,23]. Future research should focus on validating IL-8’s diagnostic and prognostic utility in larger, ethnically diverse cohorts, exploring its integration into multi-marker algorithms, and investigating its potential as a predictive biomarker for targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Additionally, mechanistic studies elucidating the role of IL-8 in the colorectal tumor microenvironment may identify novel therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting IL-8-mediated pro-tumorigenic signaling. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of IL-8’s multifaceted role in colorectal cancer may pave the way for more personalized and effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12667] [Cited by in RCA: 15544] [Article Influence: 2590.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8581] [Cited by in RCA: 8568] [Article Influence: 476.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Harada A, Sekido N, Akahoshi T, Wada T, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Essential involvement of interleukin-8 (IL-8) in acute inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 786] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (32)] |

| 4. | David JM, Dominguez C, Hamilton DH, Palena C. The IL-8/IL-8R Axis: A Double Agent in Tumor Immune Resistance. Vaccines (Basel). 2016;4:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Qazi BS, Tang K, Qazi A. Recent advances in underlying pathologies provide insight into interleukin-8 expression-mediated inflammation and angiogenesis. Int J Inflam. 2011;2011:908468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee YS, Choi I, Ning Y, Kim NY, Khatchadourian V, Yang D, Chung HK, Choi D, LaBonte MJ, Ladner RD, Nagulapalli Venkata KC, Rosenberg DO, Petasis NA, Lenz HJ, Hong YK. Interleukin-8 and its receptor CXCR2 in the tumour microenvironment promote colon cancer growth, progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1833-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Waugh DJ, Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735-6741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1408] [Cited by in RCA: 1665] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xia W, Chen W, Zhang Z, Wu D, Wu P, Chen Z, Li C, Huang J. Prognostic value, clinicopathologic features and diagnostic accuracy of interleukin-8 in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rubie C, Frick VO, Pfeil S, Wagner M, Kollmar O, Kopp B, Graber S, Rau BM, Schilling MK. Correlation of IL-8 with induction, progression and metastatic potential of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4996-5002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR, Brookland RK, Washington MK, Gershenwald JE, Compton CC, Hess KR, Sullivan DC, Jessup JM, Brierley JD, Gaspar LE, Schilsky RL, Balch CM, Winchester DP, Asare EA, Madera M, Gress DM, Meyer LR editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer, 2017. |

| 11. | Locker GY, Hamilton S, Harris J, Jessup JM, Kemeny N, Macdonald JS, Somerfield MR, Hayes DF, Bast RC Jr; ASCO. ASCO 2006 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in gastrointestinal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5313-5327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1057] [Cited by in RCA: 1135] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mahboob S, Ahn SB, Cheruku HR, Cantor D, Rennel E, Fredriksson S, Edfeldt G, Breen EJ, Khan A, Mohamedali A, Muktadir MG, Ranganathan S, Tan SH, Nice E, Baker MS. A novel multiplexed immunoassay identifies CEA, IL-8 and prolactin as prospective markers for Dukes' stages A-D colorectal cancers. Clin Proteomics. 2015;12:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bünger S, Laubert T, Roblick UJ, Habermann JK. Serum biomarkers for improved diagnostic of pancreatic cancer: a current overview. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:375-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jin WJ, Xu JM, Xu WL, Gu DH, Li PW. Diagnostic value of interleukin-8 in colorectal cancer: a case-control study and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16334-16342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Björkman K, Jalkanen S, Salmi M, Mustonen H, Kaprio T, Kekki H, Pettersson K, Böckelman C, Haglund C. A prognostic model for colorectal cancer based on CEA and a 48-multiplex serum biomarker panel. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ueda T, Shimada E, Urakawa T. Serum levels of cytokines in patients with colorectal cancer: possible involvement of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in hematogenous metastasis. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pączek S, Łukaszewicz-Zając M, Gryko M, Mroczko P, Kulczyńska-Przybik A, Mroczko B. CXCL-8 in Preoperative Colorectal Cancer Patients: Significance for Diagnosis and Cancer Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Czajka-Francuz P, Francuz T, Cisoń-Jurek S, Czajka A, Fajkis M, Szymczak B, Kozaczka M, Malinowski KP, Zasada W, Wojnar J, Chudek J. Serum cytokine profile as a potential prognostic tool in colorectal cancer patients - one center study. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020;25:867-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park JW, Chang HJ, Yeo HY, Han N, Kim BC, Kong SY, Kim J, Oh JH. The relationships between systemic cytokine profiles and inflammatory markers in colorectal cancer and the prognostic significance of these parameters. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:610-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lurje G, Zhang W, Schultheis AM, Yang D, Groshen S, Hendifar AE, Husain H, Gordon MA, Nagashima F, Chang HM, Lenz HJ. Polymorphisms in VEGF and IL-8 predict tumor recurrence in stage III colon cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1734-1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Suenaga M, Mashima T, Kawata N, Wakatsuki T, Dan S, Seimiya H, Yamaguchi K. Serum IL-8 level as a candidate prognostic marker of response to anti-angiogenic therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sanmamed MF, Perez-Gracia JL, Schalper KA, Fusco JP, Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Oñate C, Perez G, Alfaro C, Martín-Algarra S, Andueza MP, Gurpide A, Morgado M, Wang J, Bacchiocchi A, Halaban R, Kluger H, Chen L, Sznol M, Melero I. Changes in serum interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels reflect and predict response to anti-PD-1 treatment in melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1988-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 45.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ning Y, Lenz HJ. Targeting IL-8 in colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/