Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114810

Revised: October 25, 2025

Accepted: November 19, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 115 Days and 1.9 Hours

Hepatolithiasis is a common disease whose key treatment modality is hepatec

To determine the prognostic value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), albumin/alkaline phosphatase ratio (ALB/ALP), and total bilirubin (TBIL) levels in hepatolithiasis hepatectomy.

We retrospectively studied 135 patients with hepatolithiasis who underwent hepatectomy between March 2021 and August 2023. The patients were stratified into good and poor prognosis groups. We compared the general data and peri

Of 135 patients, 41 had poor prognosis. Comparative analysis revealed this group had significantly higher proportions of patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score ≥ grade II, intraoperative blood transfusion, and a history of hepatobiliary surgery. These patients also had a lower anatomical hepatectomy rate and significantly greater intraoperative blood loss (P < 0.05). Biochemically, the poor prognosis group exhibited an elevated NLR and TBIL levels, along with a significantly reduced ALB/ALP (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis confirmed ASA ≥ II, ana

The independent risk factors for poor post-hepatectomy prognosis were identified as ASA ≥ II, non-anatomical resection, high blood loss, transfusion, and prior surgery; NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL also held predictive value.

Core Tip: This study primarily compared the clinical data of patients with hepatolithiasis with good and poor prognoses following hepatectomy, analyzed the factors influencing poor prognosis, and identified scientific and reasonable indicators of poor prognosis. The novelty of this study lies in evaluating the peripheral blood levels of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), albumin/alkaline phosphatase ratio (ALB/ALP), and total bilirubin (TBIL) levels after hepatectomy and analyzing their individual and combined predictive values for poor prognosis. Notably, the NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL levels demonstrated predictive value for poor prognosis following hepatectomy, with high combined predictive efficiency.

- Citation: Yang J, Yang YX, Du QJ, Gao HW, Bai YN. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, albumin-alkaline phosphatase ratio, and bilirubin predict outcomes in hepatectomy hepatolithiasis patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 114810

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/114810.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114810

Intrahepatic bile duct stones are highly prevalent biliary diseases in East Asia, particularly in China, Japan, and South Korea. Their occurrence is related to multiple factors, including environmental factors, dietary habits, and genetic background[1]. The main feature of this disease is the formation of stones in the intrahepatic bile ducts caused by abnormal bile components (e.g., cholesterol supersaturation and calcium bilirubin precipitation), biliary tract infection, bile stasis, and abnormal biliary anatomy. These lead to changes in the physical and chemical properties of bile and eventually contribute to the formation of stones. Stones can cause biliary obstruction, secondary cholangitis, liver abscess, biliary cirrhosis, and even serious complications, such as cholangiocarcinoma[2]. The resection of a diseased bile duct can significantly reduce the possibility of stone recurrence, prevent bile duct stenosis and infection, and reduce the risk of bile duct carcinogenesis. However, post-hepatectomy complications, including bile leakage, bleeding, and infection, must be closely monitored and treated in a timely manner[3]. Timely intervention and treatment can improve the patient’s prog

We retrospectively analyzed data from 135 patients with hepatolithiasis who underwent hepatectomy between March 2021 and August 2023. Patients were classified into good and poor prognosis groups according to their postoperative prognosis. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for intrahepatic bile duct stones[6]; (2) Successful completion of open hepatectomy; (3) Absence of preoperative infectious diseases; and (4) Availability of complete clinical data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Presence of other malignant tumors, such as cholangiocarcinoma; (2) Preoperative infectious diseases or abnormal coagulation function; (3) Mental disorders or com

The clinical data of all patients were collected, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), disease course, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, hepatectomy status, hepatectomy location, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, history of hepatobiliary surgery, and complications. Fasting venous blood (5 mL) was collected within 24 hours of surgery and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes, from which the supernatant was collected. Biochemical parameters including serum albumin (ALB), ALP, TBIL, IBIL, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were analyzed using an automatic biochemical analyzer. The absolute values of neutrophils and lymphocytes were determined using a Mindray BC-5390 fully automatic blood analyzer, and the NLR was calculated.

Combined intravenous and inhalational anesthesia was administered. The patients were placed in the supine position, disinfected, and draped. A reverse L-shaped incision was made in the right upper abdomen to explore the adhesions between the liver and the diaphragm. Under ultrasonic guidance, a precut line was drawn using an electric knife. The perihepatic tough band was separated using the clamp method, the liver parenchyma was cut off, and the catheter was clamped. The bile duct stones were removed using forceps. The bile duct was examined by choledochoscopy, sutured, and closed. The common bile duct was exposed, the sphincter of Oddi was explored, and the common bile duct was sutured. A drainage tube was placed and the abdomen was closed.

The curative effect was evaluated as follows[7]: The outcomes were considered markedly effective if clinical symptoms disappeared and imaging confirmed that most of the calculi were removed, effective if the clinical symptoms improved and imaging showed a reduction in calculi, and ineffective if no significant changes were observed in the clinical symptoms or imaging findings. Patients with markedly effective or effective outcomes were classified into the good treatment group (n = 94), whereas those with ineffective outcomes were classified into the poor treatment group (n = 41).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.20.0. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD and compared using t-tests, whereas categorical data were presented as n (%) and analyzed using the χ2 test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify predictors of poor prognosis after hepatectomy, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the predictive value of the preoperative NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL levels. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

A summary of the data in each group is provided in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in terms of sex, age, BMI, disease duration, proportion of partial liver resection, liver resection site, or comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes) between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared to the good prognosis group, the poor prognosis group had a higher proportion of patients with an ASA score ≥ grade II, intraoperative blood transfusion, and a history of hepatobiliary surgery, as well as a lower proportion of patients with anatomical hepatectomy. The amount of bleeding was significantly greater in the poor prognosis group than in the good prognosis group (P < 0.001).

| Items | Good prognosis group (n = 94) | Poor prognosis group (n = 41) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Sex | 0.027 | 0.870 | ||

| Male | 45 (47.87) | 19 (46.34) | ||

| Female | 49 (52.13) | 22 (53.66) | ||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 44.53 ± 5.27 | 44.83 ± 5.45 | 0.298 | 0.766 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 21.46 ± 2.22 | 21.74 ± 2.16 | 0.678 | 0.499 |

| Course of disease (years), mean ± SD | 2.45 ± 0.50 | 2.39 ± 0.49 | 0.607 | 0.545 |

| ASA score grade II | 4 (4.26) | 7 (17.07) | 6.267 | 0.012 |

| Partial hepatectomy | 48 (51.06) | 20 (48.78) | 0.060 | 0.807 |

| Anatomical hepatectomy | 56 (59.57) | 17 (41.46) | 3.771 | 0.005 |

| Location of hepatectomy | 0.279 | 0.870 | ||

| Bilateral hepatic lobectomy | 29 (30.85) | 13 (31.71) | ||

| Left hepatic lobectomy | 31 (32.98) | 15 (36.59) | ||

| Right hepatic lobectomy | 34 (36.17) | 13 (31.71) | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL), mean ± SD | 297.66 ± 26.74 | 386.93 ± 38.72 | 15.467 | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative blood infusion | 10 (10.64) | 13 (31.71) | 8.966 | 0.003 |

| Hepatobiliary surgery history | 4.844 | 0.028 | ||

| Yes | 38 (40.43) | 25 (60.98) | ||

| No | 56 (59.57) | 16 (39.02) | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 18 (19.15) | 9 (21.95) | 0.140 | 0.708 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 15 (15.96) | 7 (17.07) | 0.026 | 0.872 |

| Diabetes | 13 (13.83) | 6 (14.63) | 0.015 | 0.902 |

The unconditional logistic regression analysis of the factors influencing poor prognosis is summarized in Table 2. Multivariate unconditional logistic regression analysis was conducted using the incidence of poor prognosis after hepatectomy as the dependent variable and ASA score ≥ grade II, anatomical hepatectomy, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, and history of hepatobiliary surgery as independent variables. Notably, an ASA score ≥ grade II, anatomical hepatectomy, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, and history of hepatobiliary surgery were all identified as factors influencing poor prognosis following hepatectomy.

| Items | β | SE | Wald | Sig | Exp (β) |

| ASA score grade II | 1.585 | 0.740 | 4.580 | 0.032 | 4.877 (1.143-20.816) |

| Anatomical hepatectomy | 1.295 | 0.459 | 7.967 | 0.005 | 3.651 (1.486-8.974) |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 0.095 | 0.019 | 24.067 | < 0.001 | 1.099 (1.158-1.142) |

| Intraoperative blood infusion | 2.135 | 0.588 | 13.189 | < 0.001 | 8.458 (2.672-26.774) |

| Hepatobiliary surgery history | 1.313 | 0.458 | 8.227 | 0.004 | 3.717 (1.515-9.115) |

A comparison of the biochemical indices of the hepatobiliary function is provided in Table 3. The NLR and TBIL levels were significantly higher in the poor prognosis group than those in the good prognosis group, whereas ALB/ALP was significantly lower (P < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in the serum IBIL, AST, or ALT levels between the two groups (P > 0.05).

| Groups | NLR | ALB/ALP | TBIL (μmol/L) | IBIL (μmol/L) | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) |

| Good prognosis group (n = 94) | 3.45 ± 0.83 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 10.25 ± 2.33 | 19.84 ± 5.49 | 10.37 ± 2.46 | 21.65 ± 5.82 |

| Poor prognosis group (n = 41) | 4.65 ± 0.94 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 12.85 ± 2.77 | 19.33 ± 5.30 | 9.64 ± 3.27 | 20.86 ± 5.52 |

| t | 7.412 | 7.504 | 5.623 | 0.501 | 1.428 | 0.736 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.617 | 0.156 | 0.463 |

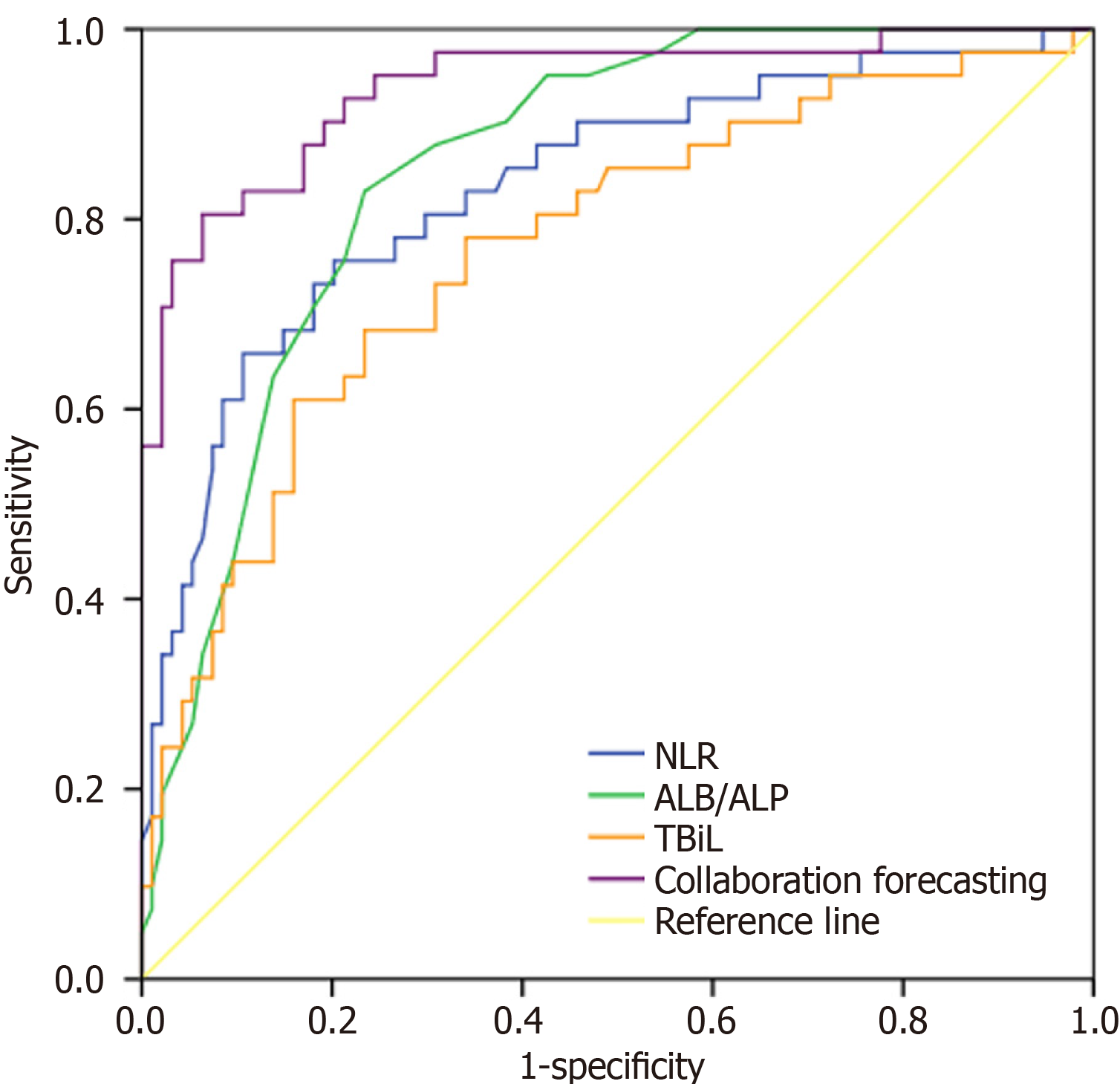

The ROC curve analysis results are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 1. The area under the curve (AUC) values for NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL levels in predicting poor prognosis of patients following hepatectomy were 0.834, 0.855, and 0.769, respectively. The combined diagnostic AUC value of the three variables was 0.939, with a sensitivity of 80.54% and a specificity of 93.58%.

| Indicator | Cut-off value | AUC | 95%CI | P value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| NLR | 4.10 | 0.834 | 0.756-0.912 | < 0.001 | 75.62 | 79.81 |

| ALB/ALP | 0.31 | 0.855 | 0.792-0.918 | < 0.001 | 82.86 | 76.59 |

| TBIL | 12.33 | 0.769 | 0.680-0.858 | < 0.001 | 61.00 | 84.00 |

| Combined detection | - | 0.939 | 0.893-0.985 | < 0.001 | 80.54 | 93.58 |

Hepatolithiasis is a common condition that occurs after hepatobiliary surgery and is characterized by the formation of stones in the intrahepatic bile ducts. Its incidence is affected by several factors[8]. Hepatolithiasis is primarily managed using non-resection approaches; however, these methods often fail to achieve complete stone removal, resulting in high recurrence rates[9,10]. Hepatectomy enables the complete removal of stones by excising the affected liver segments or lobes, as well as the diseased bile duct tissue. However, hepatectomy is a relatively major surgical procedure with certain risks, including considerable trauma, slow postoperative recovery, and a higher risk of postoperative complications, all of which may contribute to poor prognosis and affect therapeutic outcomes[11,12]. Among the 135 patients with hepatolithiasis in this study, 41 (30.37%) had poor postoperative prognosis, indicating a substantial risk. Therefore, early risk assessment following hepatectomy and corresponding intervention measures are essential.

In this study, the poor prognosis group exhibited a higher proportion of patients with an ASA score ≥ grade II. The ASA score is used to evaluate the general condition of patients before anesthesia, predict the risk of surgery, and guide anesthesia management. A score of ASA ≥ grade II indicates systemic disease. Surgery and anesthesia may also affect patient health. An ASA score ≥ grade II was identified as a risk factor for poor prognosis following hepatectomy in our study. However, some studies have suggested that the ASA score is not absolute, and patient conditions may improve with treatment and time[13]. Patients with a history of hepatobiliary surgery were overrepresented in the poor prognosis group, suggesting that this factor increases the risk of adverse outcomes. This may be because abdominal adhesions are more likely to occur after hepatobiliary surgery, resulting in increased anatomical difficulty during reoperation. Distinguishing the normal anatomical layers during reoperation is difficult, increasing the risk of injury to the surrounding organs and blood vessels. Patients with a history of hepatobiliary surgery are more likely to present with multiple complex stones[14]. In this study, patients in the poor prognosis group experienced significantly greater intraoperative blood loss and had a higher rate of intraoperative blood transfusion, indicating that substantial bleeding not only compromises intraoperative hemodynamic stability, but may also contribute to postoperative anemia, delayed recovery, and increased risk of poor prognosis. Furthermore, the proportion of patients who underwent anatomical hepatectomy was lower in the poor prognosis group, indicating that anatomical hepatectomy may be a protective factor against poor prognosis. Resection following the anatomical structure of the liver allows for a more precise removal of diseased tissue while preserving normal liver tissue, reducing intraoperative bleeding, and minimizing surgical risk[15,16].

Neutrophils are primary phagocytes in the immune system. An elevated NLR typically indicates a relative increase in neutrophils and a relative decrease in lymphocytes, potentially due to an enhanced inflammatory response or immunosuppressive state[17]. In tumors and cardiovascular diseases, an elevated NLR is associated with intensified inflammation and closely linked to poor prognosis[18]. Simultaneously, a decrease in lymphocyte levels may indicate impaired immune system function, which reduces the body’s ability to control inflammation and tumor progression. Therefore, a high NLR may indicate an increased risk of disease progression, specifically in patients with cancer, and high NLR values may be associated with poor survival and disease progression[19]. In this study, peripheral blood NLR was significantly higher in the poor prognosis group than in the good prognosis group, which is consistent with the results of previous studies. This implied a more pronounced inflammatory response and an elevated risk of complications in the poor prognosis group.

ALB is the most abundant plasma protein synthesized by the liver, which maintains plasma osmotic pressure and transports various substances, including hormones, drugs, and nutrients. Reduced serum ALB levels typically indicate impaired liver synthesis, likely due to liver or other systemic diseases[20].

ALP is expressed in the liver, bone, intestine, and other tissues, and plays a role in phosphate metabolism, particularly in the biliary system. In conditions such as gallstones or other biliary obstructive diseases, the ALP levels are typically elevated owing to impaired bile excretion, resulting in increased enzyme activity[21]. ALB/ALP is commonly used to assess liver function and disease status. In this study, a lower ALB/ALP was observed in patients with poor prognosis, likely due to decreased ALB levels and increased ALP levels, indicating impaired liver synthesis and biliary obstruction. In this study, no significant difference was observed in the classic enzymatic indicators, ALT and AST, which reflect hepatocyte injury, between the two groups. This suggests that in patients with intrahepatic bile duct stones, the degree of hepatocyte injury alone is not the key to differentiating the postoperative prognosis. In contrast, the NLR serves as a marker of systemic inflammatory responses. ALB/ALP comprehensively reflects the liver’s synthetic function and the state of biliary obstruction, whereas TBIL directly reflects the liver’s excretory and metabolic capabilities. These three indicators comprehensively capture the complex pathophysiological states that affect postoperative recovery, including systemic inflammation, nutritional status, biliary pressure, and liver function reserves. Therefore, they showed a stronger prognostic predictive value than traditional liver enzymes.

The liver is the main metabolic and detoxification organ of the body. Elevated TBIL levels are an important clinical indicator of hepatolithiasis and reflect the decreased ability of the liver to process bilirubin. Elevated TBIL levels in the peripheral blood of patients with hepatolithiasis indicate impaired liver function, decreased metabolic and detoxification functions, and inhibition of protein synthesis, including coagulation factors and other important plasma proteins, leading to postoperative coagulation dysfunction and an increased risk of intraoperative bleeding and thrombosis[22]. Systemic inflammatory responses and bile duct infection following hepatectomy in patients with hepatolithiasis increase the risk of postoperative infection, including surgical site and systemic infections. A sustained inflammatory state may lead to postoperative liver failure and affect other organ systems, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal systems, thereby increasing the overall risk of postoperative complications[23,24]. In our study, the TBIL levels were significantly higher in the poor prognosis group than in the good prognosis group, indicating that elevated TBIL levels are a contributing factor to poor outcomes following hepatectomy. Moreover, the liver and metabolic functions of patients are seriously affected after hepatectomy. ROC analysis showed that the peripheral blood levels of NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL exhibited a certain predictive value for poor prognosis, with a higher combined prediction efficiency. Despite being a single-center retrospective study with a limited sample size, these findings suggest that the postoperative measurement of peripheral blood NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL levels may be useful for predicting poor prognosis in patients with hepatolithiasis following hepatectomy. In particular, the number of cases in the poor prognosis group was relatively small, which may have affected the stability of the multivariate analysis and prediction model. In the future, multicenter prospective studies with larger sample sizes are needed to verify these findings.

Taken together, ASA ≥ II, anatomical hepatectomy, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion, and history of hepatobiliary surgery were identified as factors associated with poor prognosis following hepatectomy. Furthermore, peripheral blood NLR, ALB/ALP, and TBIL levels demonstrated a predictive value for poor prognosis following hepatectomy. Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. The relatively small sample size may have introduced a statistical bias, and the findings may not be directly generalizable to clinical practice. Moreover, we did not analyze patients with different pathological types or surgical procedures, limiting our ability to assess the factors influencing postoperative infections across these subgroups.

| 1. | Fujita N, Yasuda I, Endo I, Isayama H, Iwashita T, Ueki T, Uemura K, Umezawa A, Katanuma A, Katayose Y, Suzuki Y, Shoda J, Tsuyuguchi T, Wakai T, Inui K, Unno M, Takeyama Y, Itoi T, Koike K, Mochida S. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis 2021. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:801-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li J, Lu J, Lv S, Sun S, Liu C, Xu F, Sun H, Yang J, Wang X, Zhong X, Lu J. Linoleic acid pathway disturbance contributing to potential cancerization of intrahepatic bile duct stones into intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ban T, Kubota Y, Takahama T. Digital single-operator cholangioscopy-guided electronic hydraulic lithotripsy through an intraductal covered self-expandable metallic stent for complicated hepatolithiasis. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:e38-e39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu X, Zeng N, Hu H, Pan M, Jia F, Wen S, Tian J, Yang J, Fang C. Preliminary Exploration on the Efficacy of Augmented Reality-Guided Hepatectomy for Hepatolithiasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235:677-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhao H, Lu B. Prediction of Multiple Serum Tumor Markers in Hepatolithiasis Complicated with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:249-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xia H, Zhang H, Xin X, Liang B, Yang T, Liu Y, Wang J, Meng X. Surgical Management of Recurrence of Primary Intrahepatic Bile Duct Stones. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;2023:5158580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sakamoto Y, Takeda Y, Yamashita T, Seki Y, Kawahara S, Hirai T, Suto N, Shimosaka T, Hamamoto W, Koda H, Onoyama T, Matsumoto K, Yashima K, Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N. Comparative Study of Endoscopic Treatment for Intrahepatic and Common Bile Duct Stones Using Peroral Cholangioscopy. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nagai Y, Takagi K, Kuise T, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, Yoshida K, Yasui K, Yagi T, Fujiwara T. Multiple Hepatolithiasis Following Hepaticojejunostomy Successfully Treated with Left Hemihepatectomy and Double Hepaticojejunostomy Reconstruction. Acta Med Okayama. 2021;75:735-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liang L, Zhuang D, Feng X, Zhang K, Zhi X. The postoperative choledochoscopy in the management of the residual hepatolithiasis involving the caudate lobe: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e26996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lai MC, Geng L, Zheng SS, Deng JF. Laparoscopic ultrasound-guided superselective portal vein injection combined with real-time indocyanine green fluorescence imaging and navigation for accurate resection of localized intrahepatic bile duct dilatation: a case report. BMC Surg. 2021;21:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu L, Huang Y, Ding Z, Xu B, Luo D, Xiong H, Liu H, Huang M. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic left hepatectomy for the treatment of hepatolithiasis in patients with previous abdominal surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2022;18:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | You N, Wu K, Li Y, Zheng L. Intrahepatic Glisson Intrathecal Dissection via a Hepatic Parenchymal Transection-First Approach for Laparoscopic Anatomical Hemihepatectomy in Patients with Left/Right Glisson Pedicle Involvement. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2024;34:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu ZH, Zhou DK, Xiang YC, Zeng C, Wang WL. Huge portal venous aneurysm incidentaloma caused by intrahepatic arterioportal fistula accompany with hepatobiliary stones and cholangitis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10:288-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ren XMMM, Shen L, Zhu M, Li G. New Fiberoptic Choledochoscopy-guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Choledochoscope Lithotomy Combined with Dual-frequency Laser Lithotripsy for the Treatment of Intractable Hepatolithiasis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024;AT10323. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Benzing C, Schmelzle M, Atik CF, Krenzien F, Mieg A, Haiden LM, Wolfsberger A, Schöning W, Fehrenbach U, Pratschke J. Factors associated with failure to rescue after major hepatectomy for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A 15-year single-center experience. Surgery. 2022;171:859-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li X, Zeng X, Zhu W, Tao H, Yang J. Laparoscopic Right Hemi-hepatectomy of the Bile Duct-Obstructed Area Guided by Real-Time Fluorescence Imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:7894-7895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nishioka Y, Chun YS, Overman MJ, Cao HST, Tzeng CD, Mason MC, Kopetz SW, Bauer TW, Vauthey JN, Newhook TE; MD Anderson Cancer Center INTERCEPT Program. Effect of Co-mutation of RAS and TP53 on Postoperative ctDNA Detection and Early Recurrence after Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234:474-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li L, Xu L, Zhou S, Wang P, Zhang M, Li B. Tumour site is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: a 1:2 propensity score matching analysis. BMC Surg. 2022;22:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bai S, Shi X, Dai Y, Wang H, Xia Y, Liu J, Wang K. The preoperative scoring system combining neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and CA19-9 predicts the long-term prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients undergoing curative liver resection. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sookaromdee P, Wiwanitkit V. Total Bilirubin Levels as a Predictor of Suboptimal Image Quality of the Hepatobiliary Phase of Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced MRI in Patients with Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer: Correspondence. Korean J Radiol. 2022;23:491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tang W, Kang X, Zhou C, Chen C. The Predictive Value of the Combination of Serum RBP4, ALP, IL-1β for Postoperative Recurrence of Intrahepatic Bile Duct Stones. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2025;21:1277-1285. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Lu RY, Zhu HK, Liu XY, Zhuang L, Wang ZY, Lei YL, Wang T, Zheng SS. A Non-Linear Relationship between Preoperative Total Bilirubin Level and Postoperative Delirium Incidence after Liver Transplantation. J Pers Med. 2022;12:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Böning G, Fehrenbach U, Auer TA, Neumann K, Jonczyk M, Pratschke J, Schöning W, Schmelzle M, Gebauer B. Liver Venous Deprivation (LVD) Versus Portal Vein Embolization (PVE) Alone Prior to Extended Hepatectomy: A Matched Pair Analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:950-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Munir MM, Endo Y, Lima HA, Alaimo L, Moazzam Z, Shaikh C, Poultsides GA, Guglielmi A, Aldrighetti L, Weiss M, Bauer TW, Alexandrescu S, Kitago M, Maithel SK, Marques HP, Martel G, Pulitano C, Shen F, Cauchy F, Koerkamp BG, Endo I, Pawlik TM. Albumin-Bilirubin Grade and Tumor Burden Score Predict Outcomes Among Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma After Hepatic Resection: a Multi-Institutional Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27:544-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/