Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114336

Revised: October 27, 2025

Accepted: November 20, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 126 Days and 22.9 Hours

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical emergency, and appendectomy is essen

To investigate clinical outcomes of laparoscopic appendectomy performed during weekday daytime, weekday evening, and weekends or holidays.

The data of 977 patients who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy in a high-volume tertiary hospital between January 1, 2024, and December 31, 2024, were recruited. Patients were divided into three groups including surgeries during regular weekday in-hours (group 1), during weekday after-hours (group 2) and during weekends or extended holiday periods (group 3). Demographic, peri-, and postoperative data were compared.

There were no significant differences in operative time, conversion to open surgery, or complication rates between all groups. However, patients in the weekend/holiday group had significantly shorter time to surgery (median: 584 minutes vs 589 minutes vs 535 minutes, P = 0.002), and patients in the weekday in-hours group had significantly longer hospital stays than the other groups (median: 2 days vs 1 day vs 1 day, P < 0.001). No mortality occurred in any group.

In a well-staffed center, laparoscopic appendectomy during weekends or holidays is safe and may offer faster surgical access. Delay to surgery, not the working hour, is the main factor affecting outcomes.

Core Tip: The timing of laparoscopic appendectomy-whether during in-hours, after-hours, or weekends-does not negatively influence outcomes in well-organized tertiary centers. When performed in adequately staffed settings, weekend or holiday procedures are safe and may even allow faster surgical access. The principal factor affecting patient outcomes is surgical delay rather than the specific working hour.

- Citation: Demir M, Ekci B, Peker S, Bekraki A, Isik AL, Kilavuz H, Kurtulus I. Timing of laparoscopic appendectomy and impacts on outcomes: A retrospective study of patients across in-hours, after-hours and holidays. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 114336

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/114336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114336

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common causes of emergency abdominal surgery worldwide. It occurs in about 200 cases per 100000 people, with a lifetime risk of roughly 9% in males and 7% in females[1,2]. In the United States, the lifetime risk ranges from 7% to 8%, while in South Korea it reaches 16%[3,4]. Early diagnosis and prompt surgery are essential to prevent complications like perforation, abscess, or peritonitis. Although appendectomy is a standard procedure, outcomes can be influenced by factors such as the timing of surgery, hospital staffing, and available resources[5,6]. Some research suggests delaying surgery in uncomplicated cases doesn’t increase risks, but other studies show postponing can raise the chances of perforation and other issues[7-10]. Therefore, the timing of surgical intervention is crucial[11,12].

Previous research indicates that surgeries conducted outside regular hours may lead to higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs. These negative outcomes are often linked to lower staffing levels, healthcare worker fatigue, and limited access to diagnostic and support services during off-hours[10,13,14]. Nonetheless, the literature remains mixed, with some studies finding no significant difference in patient outcomes based on surgical timing. Many hospitals operate on shift systems during off-duty periods, resulting in variations in staffing, work hours, and hospital operations compared to regular hours[15]. Long shifts, fatigue, sleep deprivation, and reduced focus can impair clinical performance, potentially affecting outcomes for patients requiring emergency surgery[16,17].

This study aimed to assess how the timing of surgery influences clinical outcomes in patients undergoing ap

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Cam and Sakura City Hospital (Approval Code: 2025/151, Approval Date: 07 May 2025). It was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed about the surgical procedures prior to surgery and provided written informed consent.

This retrospective observational study took place at a single tertiary care center, analyzing patient records from January 1, 2024, to December 31, 2024. Eligible participants were patients aged 18 years or older who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy during this period. Exclusion criteria included patients under 18, those who had undergone an open appendectomy, and cases with missing data. General surgery specialists performed all surgeries.

Patients were categorized into three groups according to when their surgery took place.

Group 1 consisted of patients who had surgery during regular weekday in-hours (08:00 to 16:30) (n = 243).

Group 2 comprised patients who underwent surgery during weekday after-hours (16:30 to 08:00) (n = 332).

Group 3 consisted of patients who underwent appendectomy procedures during weekends or extended holiday periods (n = 402).

This classification sought to assess how the timing of surgery-especially during off-hours or holidays-affected clinical outcomes. It aimed to compare the results of laparoscopic appendectomies performed during regular weekday daytime hours with those done during nighttime shifts and extended public holidays.

Demographic and clinical data were retrospectively collected from hospital records. The data analyzed included age, sex, time from admission to surgery, duration of the procedure, intraoperative findings (perforated vs non-perforated appendix), presence of surgical drains, and conversion rates to open surgery. Additionally, radiological findings, histopathological results, intraoperative and postoperative complications, morbidity, mortality, and length of hospital stay were documented.

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized to evaluate the normality of continuous variables. Data exhibiting a normal distribution were reported as mean ± SD, whereas non-normally distributed data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Inter-group comparisons were conducted using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, as applicable. Bonferroni correction was implemented for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the potential influence of age, sex, timing group, perforation status, operative time, and time-to-surgery on postoperative complications. A P value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were executed utilizing SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

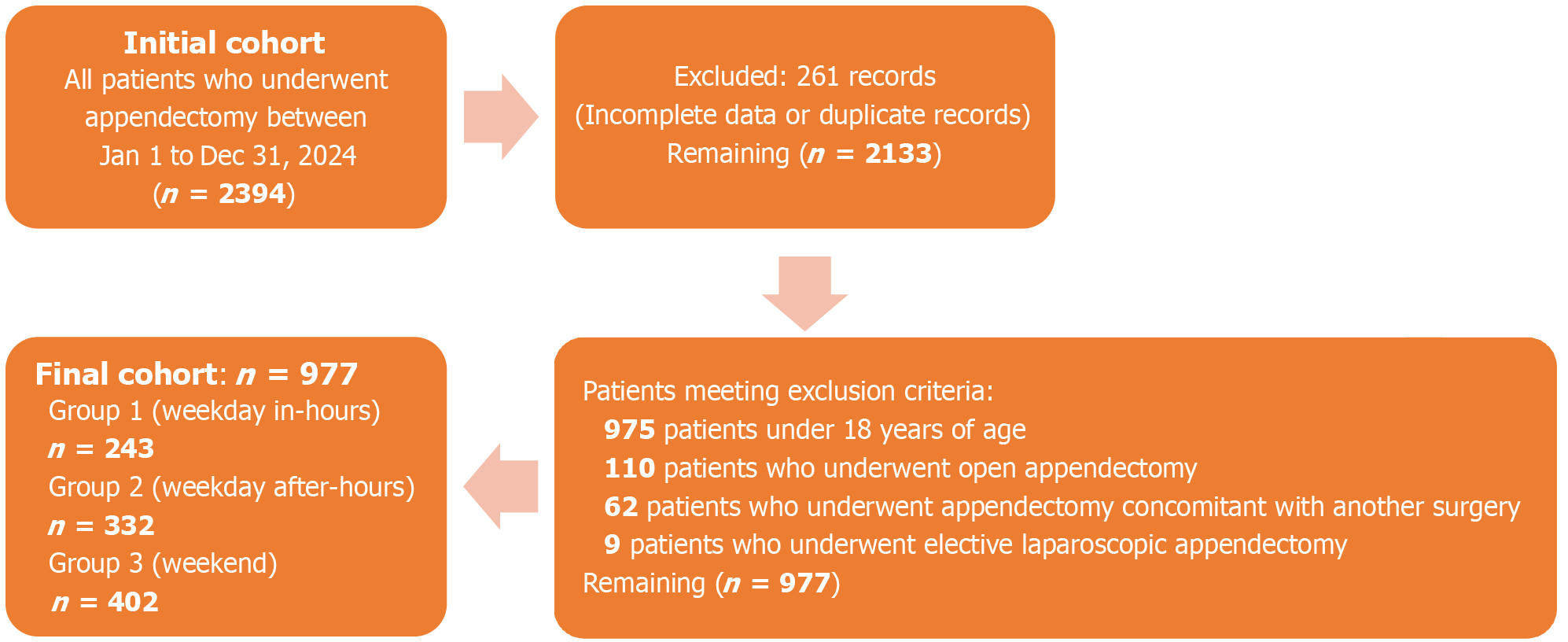

A total of 977 patients were enrolled in the study. A flowchart of the patient selection and sampling process according to the STROBE guidelines is shown in Figure 1. The distribution of demographic and perioperative variables is summarized in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in sex distribution among the groups (P = 0.297). The median age was 36 years (range: 18-91) in Group 1, 30 years (range: 18-78) in Group 2, and 32 years (range: 18-79) in Group 3.

| Group 1 (n = 243) | Group 2 (n = 332) | Group 3 (n = 402) | P value | ||||

| n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | ||

| Sex | 0.297 | ||||||

| Male | 151 (62.1) | (55.9-68) | 196 (59) | (53.7-64.2) | 225 (56) | (51.1-60.7) | |

| Female | 92 (37.9) | (32-44.1) | 136 (41) | (35.8-46.3) | 177 (44) | (39.3-48.9) | |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3 (1.2) | (0.4-3.6) | 6 (1.8) | (0.8-3.9) | 13 (3.2) | (1.9-5.5) | 0.202 |

| Presence of surgical drains | 235 (96.7) | (93.6-98.3) | 328 (98.8) | (96.9-99.5) | 392 (97.5) | (95.5-98.6) | 0.229 |

| Intraoperative findings | 0.619 | ||||||

| Perforated | 13 (5.3) | (3.2-8.9) | 15 (4.5) | (2.8-7.3) | 15 (3.7) | (2.3-6.1) | |

| Non- perforated | 230 (94.7) | (91.1-96.9) | 317 (95.5) | (92.7-97.2) | 387 (96.3) | (93.9-97.7) | |

| Med (IQR) | Med (IQR) | Med (IQR) | |||||

| Age1 | 36 (18-91) | 32-38 | 30 (18-78) | 29-33 | 32 (18-79) | 30-34 | 0.240 |

| Operative time (min)1 | 45 (35-65) | 45-50 | 45 (31.25-60) | 40-50 | 45 (35-65) | 45-50 | 0.211 |

Conversion to open surgery was necessary in 3 patients (1.2%) in Group 1, 6 patients (1.8%) in Group 2, and 13 patients (3.2%) in Group 3. This variation was not statistically significant (P = 0.202). The median operative time was consistent across all groups at 45 minutes, with IQR of 35-65 minutes for Group 1, 31.25-60 minutes for Group 2, and 35-65 minutes for Group 3 (P = 0.211). Surgical drains were utilized in 96.7%, 98.8%, and 97.5% of patients in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P = 0.229). Intraoperative observations indicated similar incidences of perforated and non-perforated appendicitis across all groups, with no statistically significant differences observed (P = 0.623) (Table 1).

The median time from admission to surgical intervention was significantly shorter in Group 3 than in Groups 1 and 2 (P < 0.05). Conversely, no statistically significant difference was identified between Groups 1 and 2 (P = 1.00) (Table 2).

| Group 1 (n = 243) | Group 2 (n = 332) | Group 3 (n = 402) | P value | ||||

| n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | n (%) | 95%CI | ||

| Intraoperative complication rate | 0 (0) | 0-1.6 | 0 (0) | 0-1.1 | 1 (0.2) | 0-1.4 | 0.489 |

| Post-op complication | 5 (2.1) | 0.8-4.7 | 8 (2.4) | 1.2-4.7 | 4 (1.0) | 0.4-2.5 | 0.314 |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 0-1.6 | 0 (0) | 0-1.1 | 0 (0) | 0-0.1 | 1.00 |

| Med (IQR) | Med (IQR) | Med (IQR) | |||||

| Time from the admission to surgery (minutes)1 | 584 (443-752) | 557-628 | 589 (415.5-777.75) | 558.5-629 | 535 (373-719.25) | 502-564.5 | 0.002 |

| (1 vs 3:0.010) | |||||||

| (2 vs 3:0.008) | |||||||

| (1 vs 2: 1.00) | |||||||

| Length of hospital stay (day)1 | 2 (1-3) | 1.0-2.0 | 1 (1-2) | 1.0-1.0 | 1 (1-2) | 1.0-1.0 | < 0.001 |

| 1 vs 2: < 0.001) | |||||||

| (1 vs 3: < 0.001) | |||||||

| (2 vs 3: 1.00) | |||||||

Intraoperative complications were infrequent, with only one case (0.2%) reported in Group 3. No complications were observed in Groups 1 or 2 (P = 0.489) (Table 2).

Postoperative complications occurred in 5 patients (2.1%) in Group 1, 8 patients (2.4%) in Group 2, and 4 patients (1.0%) in Group 3, with no significant difference (P = 0.314).

The duration of hospitalization exhibited significant variation among the groups (P < 0.001). The median length of stay was 2 days (IQR: 1-3) in Group 1, while it was 1 day (IQR: 1-2) in both Groups 2 and 3. Pairwise comparisons indicated that Group 1 experienced notably longer hospital stays compared to Groups 2 and 3 (P < 0.001), whereas no statistically significant difference was identified between Groups 2 and 3 (P = 1.00). Additionally, no cases of in-hospital mortality were observed across any of the groups (Table 2).

Table 3 presents the distribution of postoperative complications. A total of 17 patients experienced postoperative issues, with the most common being intra-abdominal abscess, abdominal hemorrhage, post-operative ileus, and surgical site infections (SSI). The overall complication rates were 2% in group 1, 0.24% in group 2, and 0.08% in group 3. No significant differences were found in the distribution of complications across the groups.

| Group 1 (n = 243) | Group 2 (n = 332) | Group 3 (n = 402) | P value | |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 3 (1.2) | 6 (0.18) | 1 (0.02) | |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (0.04) | 0 | 1 (0.02) | |

| Post-op ileus | 1 (0.04) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.02) | |

| SSI (subcutaneous) | 0 | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.02) | |

| Total | 5 (2) | 8 (0.24) | 4 (0.08) | 0.314 |

In addition to the univariate analyses, a multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of postoperative complications. The model included variables such as timing group, age, gender, time from admission to surgery, operative time, and intraoperative findings (presence of perforated or non-perforated acute appendicitis). Of these factors, only perforation status proved statistically significant (P = 0.009). Specifically, perforated appendicitis was associated with a sixfold increased risk of postoperative complications compared to non-perforated cases (Table 4).

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Group (ref: Group 1) | ||

| Group 2 | 1.209 (0.379-3.858) | 0.748 |

| Group 3 | 0.516 (0.133-2.009) | 0.340 |

| Age | 0.970 (0.931-1.010) | 0.137 |

| Gender (ref: Male) | ||

| Female | 0.860 (0.299-2.476) | 0.780 |

| Time from the admission to surgery (min) | 1.000 (0.999-1.001) | 0.502 |

| Operative time | 1.010 (0.993-1.028) | 0.253 |

| Intraoperative findings (ref: Non-perforated) | ||

| Perforated | 6.022 (1.566-23.155) | 0.009 |

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical emergency that can be either simple or complicated, such as phlegmon or appendiceal abscess. Surgery is the gold standard for treatment, but the best timing for appendectomy remains uncertain. Several studies have shown that hospital operations often vary between regular working hours and outside those hours, including evenings, weekends, and public holidays[18,19]. During these times, hospitals typically operate with fewer staff and resources due to shift systems[15]. Healthcare workers are more likely to experience long hours, fatigue, and sleep deprivation during these periods, which can negatively affect their clinical performance[16]. These issues can impact diagnostic accuracy, decision-making, and surgical outcomes, especially in emergencies[12,17]. A time-dependent increase in complication or perforation rates has been observed with in-hospital delays of 6 to 48 hours[9,13,14,20]. In countries with frequent and long public holidays, the effect of out-of-hours hospital operations might be even more significant. Holidays often disrupt everyday hospital workflows, prompting questions about whether they also affect emergency department activities. Such changes are believed to cause delays in diagnosis or surgery and decrease the quality of operative care. Few studies have directly examined how holiday-related delays influence surgical outcomes during extended holiday periods in these healthcare systems[11,19].

This study aimed to assess whether the timing of surgery affects clinical outcomes in patients undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy during weekday in-hours, weekday after-hours, and weekends or long public holidays. By examining perioperative and postoperative variables across these groups, we sought to determine whether operative timing is associated with differences in complication rates, length of hospital stay, or overall patient outcomes. These results will help establish staffing policies and workflow planning in emergency surgical care.

Several studies have examined how the timing of surgery affects the outcomes of laparoscopic appendectomy. Kim and Kang[21] reported no significant differences in operative time, complications, or recovery between surgeries performed during or after hours. The day of discharge was not associated with higher readmission rates[22]. Consistent with this, Shen et al[18] and Mönttinen et al[23] found that outcomes did not significantly differ between daytime and nighttime procedures. Lane et al[24] also observed no significant differences between weekday and weekend cases, except for a slightly higher rate of SSI in weekday patients. A similar finding was noted in a study that grouped surgeries by time of day, which showed no difference unless the operation was delayed by more than 24 hours[10].

Other research emphasizes the risks associated with delayed surgery. Al-Qurayshi et al[9] found that delays and weekend admissions were associated with longer hospital stays and increased complications. A large-scale analysis of over 855000 cases indicated that delaying surgery beyond 12 hours in complex cases and 24 hours in simpler cases significantly increased the risk of adverse outcomes[7]. Hospital resources and staffing levels also play a critical role. Ozdemir et al[15] observed higher weekend mortality rates in hospitals with fewer staff. Our results support the view that surgery delays, rather than the timing within the day or week, primarily influence outcomes. While perforation rates showed no significant difference, earlier surgeries demonstrated a positive trend, consistent with Drake et al[25], who reported that performing surgery within 8.6 hours helps prevent perforation.

Our study, conducted at a busy tertiary hospital with 977 patients, categorized patients by the timing of their surgery: Weekday in-hours (Group 1), weekday after-hours (Group 2), or weekend or holiday (Group 3). We observed that Group 3 patients had a significantly shorter interval from admission to surgery than the other groups. However, there was no significant difference in overall complication rates among the groups, and no mortalities occurred in any group. Ope

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single, well-equipped tertiary hospital. Consequently, these findings may not be generalizable to smaller or resource-limited centers. Second, the retrospective nature of the study design limits our ability to establish causal relationships and account for all confounding variables, such as comorbidities or reasons for delays. Third, the surgical teams were not standardized; although all surgeons had specialized training, variations in experience and decision-making could influence outcomes.

At a well-equipped center, laparoscopic appendectomies performed on weekends and holidays proved to be safe and effective. Patients experienced shorter intervals from admission to surgery and shorter hospital stays than those operated on weekdays during working hours. Our findings challenge the assumption that weekend surgeries carry higher risks. Instead, they highlight a more crucial point: The timing of the surgery-specifically, how long the appendix remains untreated-is more important than the day of the week.

| 1. | Guan L, Liu Z, Pan G, Zhang B, Wu Y, Gan T, Ouyang G. The global, regional, and national burden of appendicitis in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coward S, Kareemi H, Clement F, Zimmer S, Dixon E, Ball CG, Heitman SJ, Swain M, Ghosh S, Kaplan GG. Incidence of Appendicitis over Time: A Comparative Analysis of an Administrative Healthcare Database and a Pathology-Proven Appendicitis Registry. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1307] [Cited by in RCA: 1337] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee JH, Park YS, Choi JS. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in South Korea: national registry data. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bonomo RA, Tamma PD, Abrahamian FM, Bessesen M, Chow AW, Dellinger EP, Edwards MS, Goldstein E, Hayden MK, Humphries R, Kaye KS, Potoski BA, Rodríguez-Baño J, Sawyer R, Skalweit M, Snydman DR, Donnelly K, Loveless J. 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America on Complicated Intra-abdominal Infections: Diagnostic Imaging of Suspected Acute Appendicitis in Adults, Children, and Pregnant People. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;79:S94-S103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alvarez-Lozada LA, Fernandez-Reyes BA, Arrambide-Garza FJ, García-Leal M, Alvarez-Villalobos NA, Martínez-Garza JH, Fernández-Rodarte B, Elizondo-Omaña RE, Quiroga-Garza A. Clinical scores for acute appendicitis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Am J Surg. 2025;240:116123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uttinger K, Baum P, Diers J, Seehofer D, Germer CT, Wiegering A. The impact of surgical timing on outcome in acute appendicitis in adults: a retrospective observational population-based cohort study. Int J Surg. 2024;110:4850-4858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Dijk ST, van Dijk AH, Dijkgraaf MG, Boermeester MA. Meta-analysis of in-hospital delay before surgery as a risk factor for complications in patients with acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2018;105:933-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Qurayshi Z, Kadi A, Srivastav S, Kandil E. Risk and outcomes of 24-h delayed and weekend appendectomies. J Surg Res. 2016;203:246-252.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Canal C, Lempert M, Birrer DL, Neuhaus V, Turina M. Short-term outcome after appendectomy is related to preoperative delay but not to the time of day of the procedure: A nationwide retrospective cohort study of 9224 patients. Int J Surg. 2020;76:16-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Skjold-Ødegaard B, Braut GS, Ersdal HL, Søreide K. Claims filed after perceived malpractice in management of acute appendicitis: An observational nationwide cohort study. Scand J Surg. 2025;14574969251363823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Estefany VA, Karen MM, Citlali AG, Ailema GO, Jose Francisco GZ. Surgical delay in appendicitis among children: the role of social vulnerability. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1591200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ashkenazi I, Zeina AR, Olsha O. In-hospital delay of surgery increases the rate of complicated appendicitis in patients presenting with short duration of symptoms: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:3879-3886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jiang L, Liu Z, Tong X, Deng Y, Liu J, Yang X, Chan FSY, Fan JKM. Does the time from symptom onset to surgery affect the outcomes of patients with acute appendicitis? A prospective cohort study of 255 patients. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2021;14:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ozdemir BA, Sinha S, Karthikesalingam A, Poloniecki JD, Pearse RM, Grocott MP, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Mortality of emergency general surgical patients and associations with hospital structures and processes. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:54-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sturm L, Dawson D, Vaughan R, Hewett P, Hill AG, Graham JC, Maddern GJ. Effects of fatigue on surgeon performance and surgical outcomes: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:502-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cortegiani A, Ippolito M, Misseri G, Helviz Y, Ingoglia G, Bonanno G, Giarratano A, Rochwerg B, Einav S. Association between night/after-hours surgery and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:623-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shen L, Zhang L, Shi H. Outcomes of Daytime and Night-Time Appendectomies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2024;34:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cook SJ, O'Driscoll KM, Al Maksoud A, Evoy D, McCartan D, Heneghan HM, Prichard RS. Time to surgery for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in an adult university teaching hospital. Surgeon. 2025;23:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fair BA, Kubasiak JC, Janssen I, Myers JA, Millikan KW, Deziel DJ, Luu MB. The impact of operative timing on outcomes of appendicitis: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Project analysis. Am J Surg. 2015;209:498-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim H, Kang BM. Out-of-Hours Laparoscopic Appendectomy: A Risk Factor for Postoperative Complications in Acute Appendicitis? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2025;35:103-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Albabtain IT, Alhassan NF, Alsuhaibani RS, Almalki SA, Arishi HA, Alhaqbani AS, Alyami RA. Outcomes of emergency appendectomies and cholecystectomies performed at weekends. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:4005-4010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mönttinen T, Kangaspunta H, Laukkarinen J, Ukkonen M. Nighttime Appendectomy is Safe and has Similar Outcomes as Daytime Appendectomy: A Study of 1198 Appendectomies. Scand J Surg. 2021;110:227-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lane RS, Tashiro J, Burroway BW, Perez EA, Sola JE. Weekend vs. weekday appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, effects on outcomes and operative approach. Pediatr Surg Int. 2018;34:621-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Drake FT, Mottey NE, Farrokhi ET, Florence MG, Johnson MG, Mock C, Steele SR, Thirlby RC, Flum DR. Time to appendectomy and risk of perforation in acute appendicitis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:837-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Smith SA, Yamamoto JM, Roberts DJ, Tang KL, Ronksley PE, Dixon E, Buie WD, James MT. Weekend Surgical Care and Postoperative Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Med Care. 2018;56:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Matoba M, Suzuki T, Ochiai H, Shirasawa T, Yoshimoto T, Minoura A, Sano H, Ishii M, Kokaze A, Otake H, Kasama T, Kamijo Y. Seven-day services in surgery and the "weekend effect" at a Japanese teaching hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Van Essen D, Vergouwen M, Sayre EC, White NJ. Orthopaedic trauma on the weekend: Longer surgical wait times, and increased after-hours surgery. Injury. 2022;53:1999-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Takagi H, Ando T, Umemoto T; ALICE (All-Literature Investigation of Cardiovascular Evidence) group. A meta-analysis of weekend admission and surgery for aortic rupture and dissection. Vasc Med. 2017;22:398-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ranganathan S, Riveros C, Tsugawa Y, Geng M, Mundra V, Melchiode Z, Ravi B, Coburn N, Jerath A, Detsky AS, Wallis CJD, Satkunasivam R. Postoperative Outcomes Following Preweekend Surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2458794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Redelmeier DA, Bell CM. Weekend worriers. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1164-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/