Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.111928

Revised: August 6, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 192 Days and 12.6 Hours

Septic shock disrupts systemic and organ-specific microcirculation, leading to poor tissue perfusion and impaired healing. While mesenteric hemodynamics have been studied, the impact of sepsis on intestinal microcirculation and ana

To assess the short-term effects of septic shock on microcirculation in the small intestine and colon, with a focus on hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses, using laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI).

Ten pigs underwent midline laparotomy with the creation of four anastomoses: One hand-sewn and one stapled anastomosis in both the small intestine and colon. LSCI measurements were taken before anastomosis formation (TB), imme

Septic shock significantly reduced microcirculation in both untouched intestine and anastomoses. Hand-sewn anastomoses consistently exhibited higher perfusion than stapled anastomoses. At T150, perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses remained significantly higher than in stapled anastomoses (51% vs 34% of TB, P = 0.002).

This study shows that septic shock significantly impairs intestinal microcirculation indicating a risk of intestinal ischemia if bacteriaemia and subsequent septic shock is untreated. Due to diminish blood flow following septic shock, the anastomotic healing may be compromised leading to increased risk of anastomotic leakage. Conclu

Core Tip: Septic shock profoundly affects intestinal blood flow, yet its impact on surgical anastomoses remains unclear. In this study, we used laser speckle contrast imaging in a porcine model to assess microcirculation in the small intestine and colon during induced septic shock. We demonstrate a significant reduction in microcirculation, especially at anastomotic sites, with hand-sewn anastomoses maintaining higher perfusion than stapled ones. These findings highlight the potential risk of impaired anastomotic healing during sepsis and emphasize the importance of optimizing surgical strategies in septic patients.

- Citation: Paramasivam R, Jaensch C, Kristensen NM, Paramasivam SS, Woldeselassie H, Jensen LK, Madsen AH, Ørntoft MBW. Septic shock reduces intestinal microcirculation and anastomotic perfusion: A porcine laser speckle contrast imaging study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 111928

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/111928.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.111928

Sepsis is a complex and life-threatening condition that disrupts multiple organ systems, including the microcirculation[1]. The effects of sepsis on mesenteric blood flow and its underlying pathophysiology have been extensively studied[2-4]. Sepsis, characterized by systemic inflammation and the release of toxins, can cause profound alterations in the splanchnic circulation, including reduced mesenteric perfusion and intestinal ischemia[5-8]. Nevertheless, our understanding of how intestinal microcirculation and healing is affected during sepsis remains limited[9]. Some studies have demonstrated higher rates of complications, such as anastomotic leakage (AL) and delayed wound healing, likely due to compromised tissue perfusion[10,11]. However, other studies have suggested that performing an anastomosis in emergency colorectal surgery is safe, with no increased overall risk of AL[12]. Nonetheless, these studies also report a significantly higher risk of AL if the patient remains septic and requires vasopressor therapy during secondary anastomoses. Subsequently, the management of patients with sepsis, whether preexisting or developing postoperatively, remains without clear evidence-based guidelines.

Experimental studies using advanced imaging techniques, such as Sidestream Dark Field (SDF) imaging[13] and Laser Doppler Flowmetry (LDF)[14,15], have demonstrated significant reductions in intestinal microcirculation during sepsis. These findings strongly support the hypothesis that ischemic injury to the gut plays a pivotal role in sepsis-related surgical complications. However, these studies also have notable limitations. In the LDF study[14], the sepsis model was based on fecal peritonitis, which itself is a known risk factor for postoperative complications, potentially confounding the results and limiting the applicability of the findings in other sepsis etiologies. Similarly, the SDF study[13] measured intraluminal microcirculation in the small intestine via a stoma and in the colon only through the rectum. This restricted sampling approach may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the microvascular changes throughout the entire intestinal tract. Thus, critical questions are still unanswered about the safety and outcomes of surgical interventions in septic patients.

To date, no studies have directly evaluated the effects of sepsis on intestinal anastomoses or their healing potential. This study aims to bridge this gap by using laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) to investigate the direct effects of septic shock on the microcirculation of both the colon and small intestine, as well as the impact on hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses. As a novel imaging modality, LSCI offers significant advantages by enabling repeated, quantitative measurements of microcirculation under dynamic conditions, providing a robust and detailed assessment that may help inform clinical decision-making[16-18]. By exploring how sepsis influences intestinal microcirculation, this study seeks to provide insights that could inform clinical practice; especially concerning acute intestinal surgery.

The impact of septic shock on the microcirculation of the small intestine and colon, as well as hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses in both small intestine and the colon, was assessed using an experimental setup in a porcine model.

The anesthesia protocol for the porcine model has been described in detail previously[18]. Briefly, ten female Danish Landrace/Yorkshire/Duroc pigs, weighing an average of 43.35 ± 2.5 kg and aged 14-16 weeks, were sedated, and anesthetized. Propofol and fentanyl infusions-maintained anesthesia throughout the experiment. The animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated, receiving Lactated Ringer's solution at a rate of 5 mL/kg/hour. The septic response was defined by characteristic alterations in systemic physiology, including a progressive decline in hemo

The Escherichia coli (E. coli) sepsis model used in this study has been described previously[19]. In summary, cultures of E. coli (strain ATCC 25922, Department of Medical Microbiology, Aarhus University Hospital) were grown on 5% sheep blood agar plates (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 24 hours at 37 °C. During the log phase of growth, colonies were harvested from the agar surface, suspended in normal saline and then adjusted to OD620 = 1.2 (approximately 1 × 109 CFU/mL). The following day, the bacterial suspension was serially diluted in triplicates and plated on to sheep blood agar plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C followed by CFU enumeration on the agar plates, to verify the concentration and ensure accuracy. Prior to administration, the suspension was stored at 4 °C to prevent bacterial replication under low-oxygen conditions of the infusate.

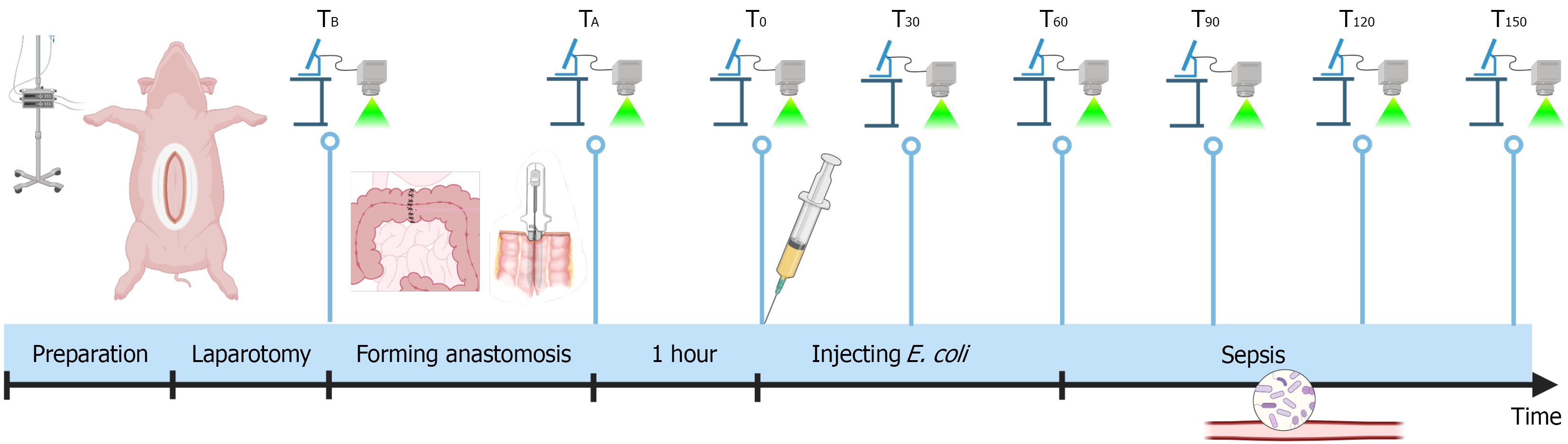

Following induction of general anesthesia, a midline laparotomy was performed to expose the small intestine and colon. In each pig, two types of anastomoses were created: A single-layer, hand-sewn seromuscular end-to-end anastomosis[20] and a stapled anti-mesenteric side-to-side anastomosis[21] on both the small intestine and colon, resulting in a total of four anastomoses per pig. LSCI measurements were systematically performed on all four anastomoses, as well as on predefined untouched segments of the small intestine and colon, following a standardized protocol (Figure 1). Baseline measurements (TB) were made prior to anastomosis formation, with additional measurements immediately after the anastomoses were completed (TA). The intestines were then allowed to rest for one hour without further surgical manipulation, after which the T0 measurements were obtained. Sepsis was induced by intravenously injection of live E. coli (ATCC 25922). The initial infusion rate was set at 16 mL/hour, and the rate was doubled every 10 minutes until approximately 240 mL of the E. coli solution had been administered. LSCI measurements and arterial blood gas analyses were performed at 30-minute intervals, starting at T30. This continued until T150, after which the pigs were euthanized.

Microcirculation was evaluated using LSCI at a wavelength of 785 nm (MoorFLPI-2, Moor Instruments, Axminster, United Kingdom). This method enabled assessment of microcirculation to a depth of approximately 1 mm. The LSCI device was positioned 25 cm above the intestinal surface, ensuring coverage of at least 5 cm on either side of the region of interest (ROI). Measurements were captured over a 30-second period with a sampling rate of 25 frames per second[22]. Results were presented both as a picture heatmap and in arbitrary Laser Speckle Perfusion Units (LSPU).

Tissue samples from the small intestine and colon were collected at baseline and at the end of the experiment. These samples were sent for histological analysis to evaluate any changes associated with E. coli sepsis. Briefly, the biopsies were fixated in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed through graded concentrations of alcohol and embedded in paraffin wax. Tissue sections were cut (4 µm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). HE stained sections were evaluated patho-morphologically with special focus on identifying (yes/no) an acute inflammatory response. The following parameters were evaluated in mucosa and submucosae, respectively; epithelial damage, hemorrhage, hyperemia, edema, neutrophil infiltration, and necrosis.

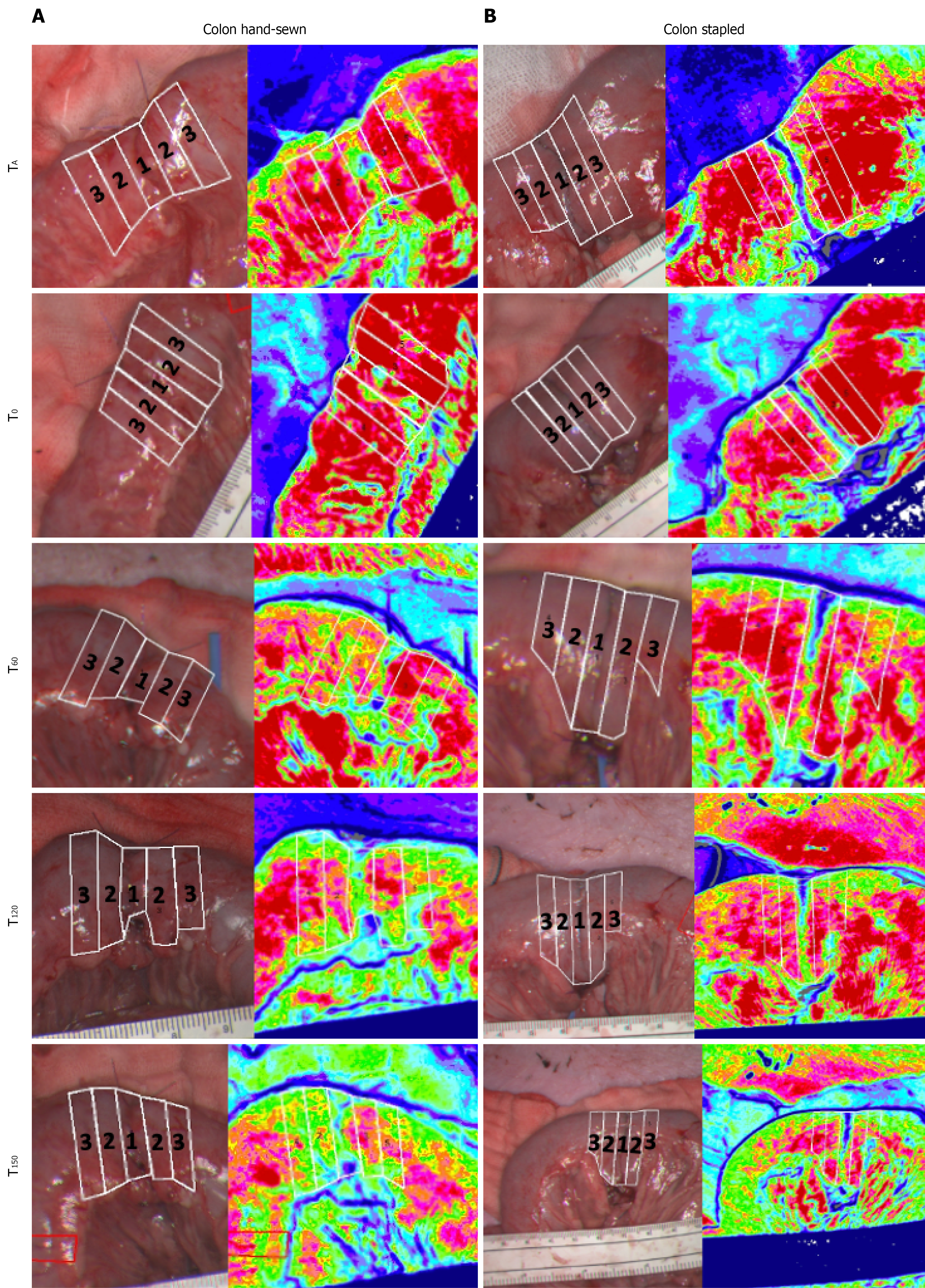

Four ROIs were selected for analysis (Figure 2) for each anastomosis. ROI 1 was centered directly on the anastomosis, ROI 2 was positioned 5 mm away from the anastomosis on either side, ROI 3 was located 10 mm from the anastomosis on either side, and the final ROI was placed on a predefined untouched segment of the small intestine/colon. Each ROI measured 5 mm in width and spanned the entire intestinal diameter, with ROI 1-3 arranged adjacently. Median microcirculatory values in LSPU were calculated for each ROI. Data were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models with repeated measures to account for within-subject variability. Model residuals were visually assessed for normality and further evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Results were presented as LSPU changes relative to baseline, which was defined as the average LSPU across all ten animals in the study at TB. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, United States), while microcirculation flux data were processed using MoorFLPI2 Research software v2.x (Moor Instruments, Axminster, United Kingdom).

All ten pigs underwent surgery without complications or adverse events. To induce septic shock, an average of 235.5 mL of E. coli suspension was administered (range: 210-240 mL), with a mean bacterial concentration of 1.11 × 109 CFU/mL (range: 8 × 108 CFU/mL to 1.4 × 109 CFU/mL).

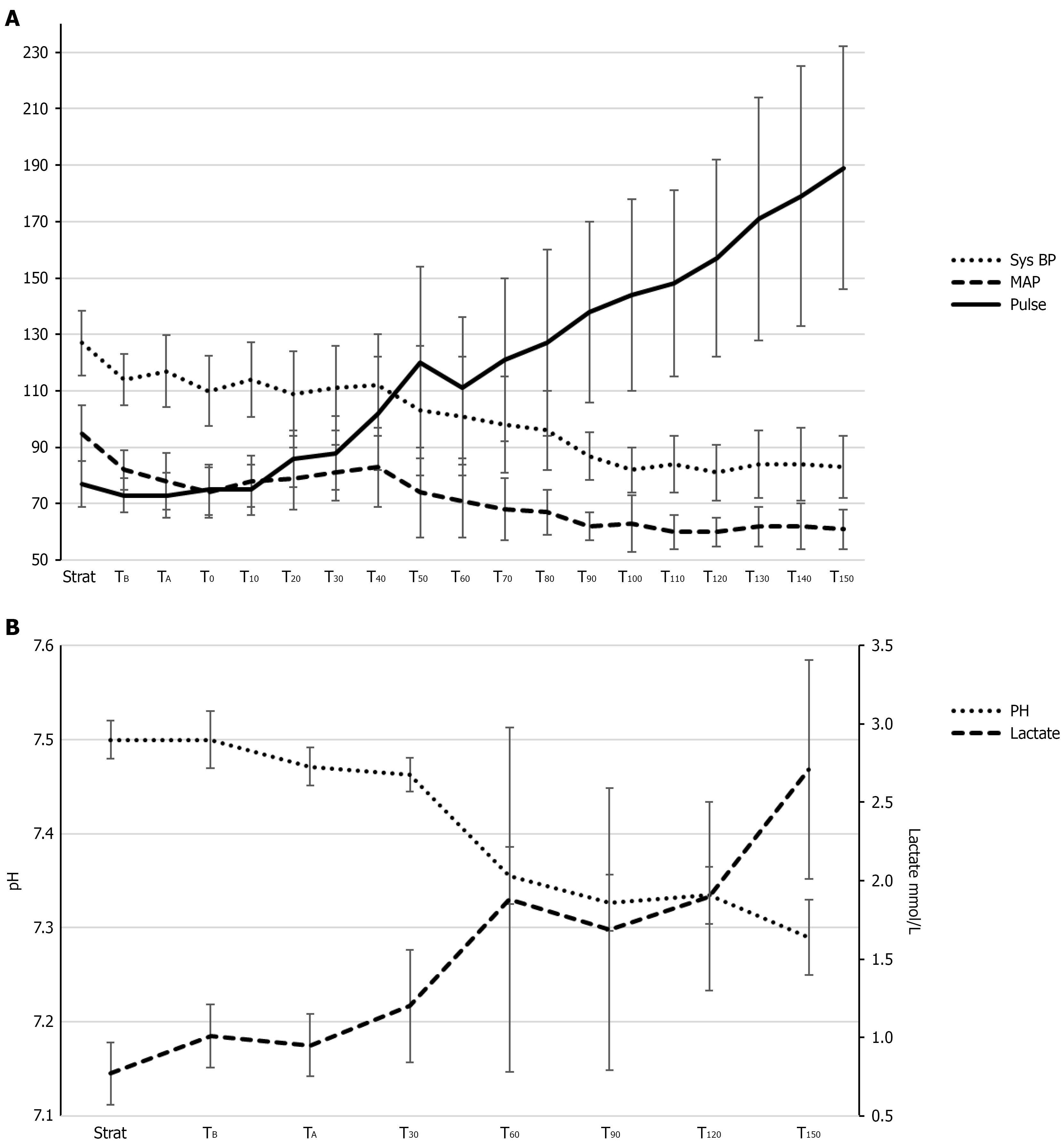

The hemodynamic data (Figure 3) during sepsis show a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure (P < 0.001) and MAP (P < 0.001), accompanied by a significant increase in pulse (P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant reduction in pH levels (P < 0.001) and a significant increase in lactate levels (P < 0.001).

LSCI measurements were successfully performed at all predefined time points in all pigs. Representative LSCI images illustrating microcirculation around the anastomoses are shown in Figure 2 (colon) and Supplementary Figure 1 (small intestine).

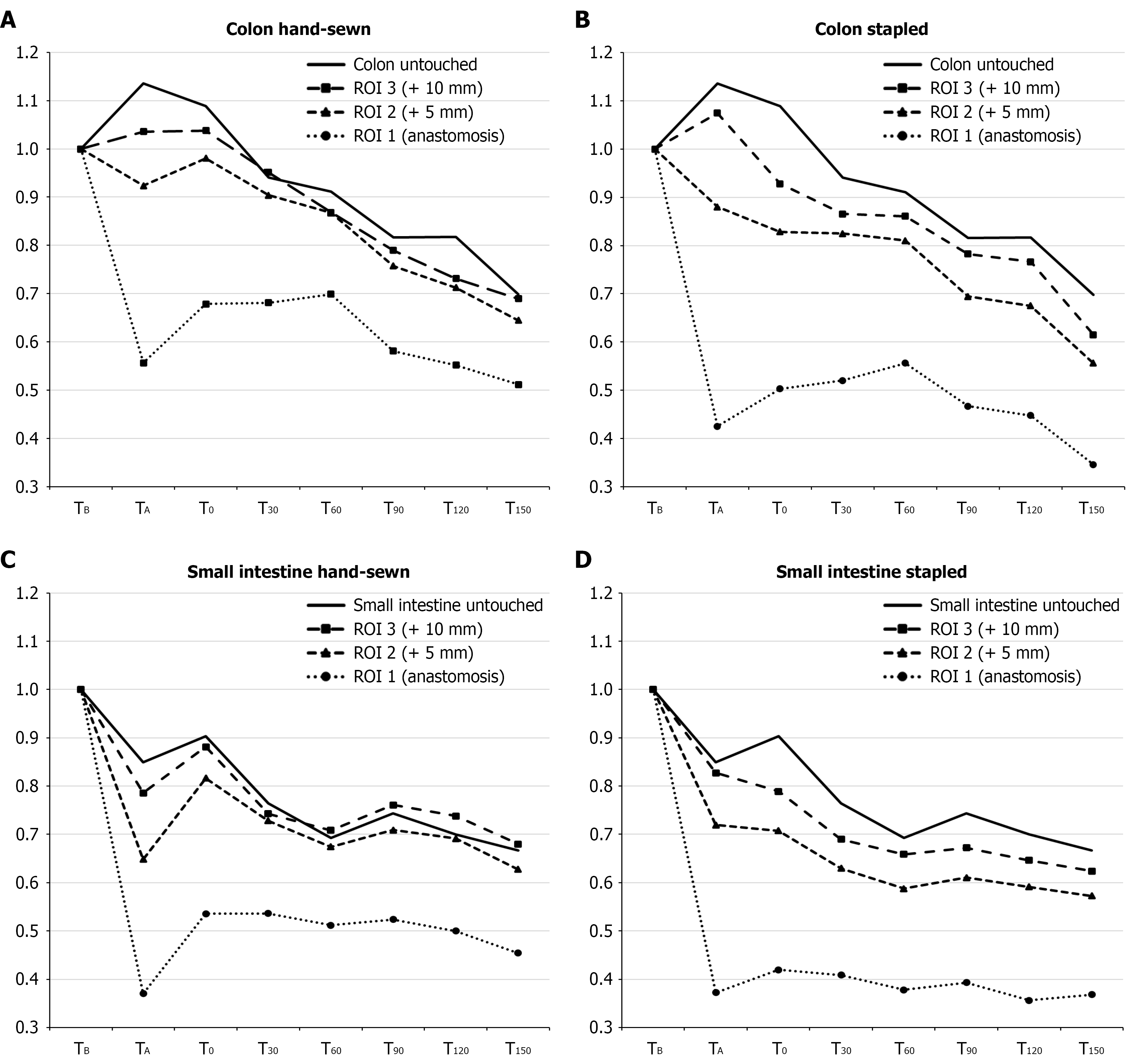

Relative changes in LSPU compared to baseline are presented in Figure 4, while absolute LSPU values are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

In the untouched colon, no statistically significant difference in microcirculation was seen during anastomosis formation or after 1 hour of rest. After E. coli infusion, a decline was seen: Perfusion continued to drop over time, reaching statistically significant reductions at T60 (91%, 95%CI: 80%-99%); T90 (81%, 95%CI: 80%-86%); and T150 (69%, 95%CI: 60%-78%). In the untouched small intestine, a significant reduction in perfusion was observed already during anastomose formation, with a drop to 84% (95%CI: 80%-88%). After one hour of rest, perfusion increased slightly to 90% (95%CI: 85%-95%), though still significantly lower than baseline. After E. coli infusion, perfusion declined further to 76% of baseline (95%CI: 70%-82%) at T30; 69% (95%CI: 60%-74%) at T60; and 66% (95%CI: 60%-71%) at T150 (Figure 4). All measurements following E. coli infusion were statistical significant lower compared to baseline.

ROI 1, anastomosis: The perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses at TA was 55% of baseline (95%CI: 43%-67%), which was significantly higher than the perfusion observed in stapled anastomoses of 42% (95%CI: 35-49) (P = 0.011). This finding persisted throughout the study: After 1 hour rest (T0), perfusion increased in both groups and was significantly higher in hand-sewn anastomoses; After E. coli infusion, the perfusion levels decreased and at T150, perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses dropped to 51% of baseline (95%CI: 40%-63%), whereas the stapled anastomoses’ perfusion dropped to 34% (95%CI: 30%-43%) which was significantly lower than the hand-sewn anastomoses (P = 0.002).

ROI 2, ± 5 mm adjacent to the anastomosis: Perfusion within 5 mm of the anastomosis was higher than at ROI 1 for hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses after the anastomosis formation (92% vs 88%). This finding persisted at T0 through to T150, where perfusion adjacent to hand-sewn anastomoses decreased to 64% (95%CI: 50%-75%) compared to 55% (95%CI: 50%-65%) in stapled anastomoses.

ROI 3, ± 10 mm adjacent to the anastomosis: At ± 10 mm from the anastomosis, no significant differences were observed between hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses across all time points compared to baseline. After E. coli infusion, the impact on perfusion was similar to that seen in untouched intestine, with microcirculation at T150 reduced to 68% of baseline (95%CI: 60%-80%) for hand-sewn anastomoses and 61% of baseline (95%CI: 50%-69%) for stapled anastomoses.

In summary, microcirculation across all ROIs during sepsis was significantly reduced compared to baseline. Hand-sewn anastomoses consistently demonstrated higher perfusion than stapled anastomoses at all time points, with statistically significant differences observed at the anastomotic site itself. In contrast, differences between hand-sewn and stapled techniques were less pronounced at ± 5 mm and ± 10 mm from the anastomosis, where a more gradual decline in perfusion was observed - mirroring the pattern seen in the untouched colon.

ROI 1, anastomosis region: In the anastomosis region, perfusion after anastomosis formation was similar between hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses, with values of 37% (95%CI: 30%-43%) and 37% (95%CI: 32%-42%) of baseline, respectively (P = 0.952). However, significant differences emerged during subsequent time points. At T0, perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses increased to 53% (95%CI: 49%-57%), compared to 41% (95%CI: 36%-47%) in stapled anastomoses (P = 0.010). During sepsis, perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses continued to decrease significantly less relative to stapled anastomoses; at T150, the perfusion in hand-sewn anastomoses was 45% (95%CI: 40%-54%), and in stapled anastomoses 36% of baseline (95%CI: 30%-42%, P = 0.014), respectively.

ROI 2, ± 5 mm adjacent to the anastomosis: At ROI 2, microcirculation was generally higher than at the anastomosis site. At TA no significant difference was found in stapled anastomoses (71%, 95%CI: 67%-76%) compared to hand-sewn anastomoses (64%, 95%CI: 59%-69%, P = 0.071). At T0, perfusion was significantly higher in hand-sewn anastomoses (81%) compared to stapled anastomoses (70%, P = 0.004). Similar findings were observed at T30, T90, and T150, where perfusion decreased to 62% (95%CI: 60%-68%) for hand-sewn anastomoses and 57% (95%CI: 50%-62%) for stapled anastomoses (P = 0.005).

ROI 3, ± 10 mm adjacent to the anastomosis: At ± 10 mm from the anastomosis, perfusion was similar between hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses after anastomosis formation (78% vs 82%, P = 0.303). At T0, hand-sewn anastomoses had significantly higher perfusion (88%, 95%CI: 83%-92%) than stapled anastomoses (78%, 95%CI: 74%-82%, P = 0.031). Similar differences were found at T90, T120, and T150, where perfusion declined to 67% (95%CI: 60%-74%) in hand-sewn anastomoses and 62% (95%CI: 60%-68%) in stapled anastomoses (P = 0.026).

Recapitulating, hand-sewn anastomoses had consistently higher perfusion compared to stapled anastomoses, particularly within the anastomosis region and at ± 5 mm from the site. Differences at ± 10 mm were less pronounced, but still statistically significant one hour after E. coli sepsis was induced.

Histological results are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and revealed no significant abnormalities in the small intestine or colon. The most common observation was post-operative hyperemia in the colon, characterized by an increased presence of red blood cells within the vessels compared to baseline. In a few samples, an elevated number of neutrophils were noted on the epithelial surface, particularly between villi and within crypts. However, no infiltration was observed in the mucosal or submucosal layers.

This study provides novel insights into the effects of septic shock on intestinal microcirculation, comparing untouched segments of the small intestines and colon to hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses: We demonstrated a significant and progressive decline in microcirculation in both untouched bowel and especially anastomotic regions during septic shock. This may indicate that septic shock impairs intestinal perfusion in general and especially around surgical resection sites, which we hypothesize could impair intestinal healing and increase e.g., anastomotic leak rates. Thus, our findings contribute to our understanding of microcirculatory changes during sepsis and raise important considerations for surgical decision-making in septic patients.

Our sepsis model effectively induced a state of septic shock, as demonstrated by significant reductions in systemic parameters, including MAP and pH, alongside elevated lactate levels. These findings are consistent with established septic shock models. Unlike other studies, such as Krejci et al[14], who utilized fecal peritonitis as the sepsis model, our approach avoided localized peritoneal contamination. Despite this, the intestines still exhibited pronounced microcirculatory impairments, emphasizing the systemic effects of sepsis on intestinal perfusion, independent of localized contamination.

Furthermore, unlike the SDF study[13], which assessed intraluminal microcirculation, our use of LSCI allowed for direct, repeated measurements on both the small and large intestine, including anastomoses. This comprehensive approach provides a more detailed and accurate representation of intestinal microcirculation under septic conditions, enhancing the translational relevance of our findings.

First, our results demonstrate a consistent and significant decline in microcirculation in both the untouched colon and small intestine during septic shock. A notable finding was the difference in microcirculatory responses between the untouched small intestine and colon; The small intestine exhibited a higher baseline perfusion, which may explain the more pronounced reduction observed during sepsis. In contrast, the colon demonstrated a more gradual decline in perfusion. The general decline in both colonic and small intestinal perfusion aligns with the existing understanding of the splanchnic circulatory response to sepsis, where mesenteric blood flow is redistributed to other critical organs (lung, heart, kidney) at the expense of the bowel[15]. The observed decrease in perfusion could predispose intestinal tissue to ischemia, which raises concerns in cases with both sepsis and surgical treatment including anastomosis formation. To evaluate the effect of surgery on anastomoses and whether normal pathological processes were disturbed during sepsis, tissue was sampled for histological analysis. However, these revealed no significant pathological changes: The primary histological finding was pronounced hyperemia and vascular stasis, consistent with the early vascular phase of the acute inflammatory response[23]. It is important to note that cellular signs of inflammation, such as neutrophil infiltration, are typically not evident histologically until approximately two hours after the onset of injury, with infiltration peaking around 24 hours. These findings reflect the relatively short duration of the experiment (2.5 hours). If histopathological changes are to accurately reflect impaired healing following sepsis, tissue sampling should be performed 4-7 days postoperatively[24], as studies have shown this to be the typical timeframe for the development of AL. However, such a setup was beyond the ethical permission given for this porcine model, but could be integrated in a future research model.

Second, our study indicates that in cases where anastomoses are made during sepsis, hand-sewn anastomoses present consistently higher perfusion compared to stapled anastomoses across all time points. This suggests that hand-sewn techniques may preserve microcirculatory integrity better than stapled approaches during sepsis and increase the healing potential. However, both types of anastomoses experienced significant declines in perfusion during sepsis, which underlines that cautious surgical planning in septic patients is necessary; salvage surgery without primary anastomosis could be preferable until the septic condition is treated to reduce the risk of AL from impaired microcirculation. Previous research has suggested that the lower threshold for safe anastomotic perfusion is a 30% reduction in microcirculation[25]; In our study, we demonstrate that sepsis reduced the intestinal microcirculation at the untouched intestine with 33% for the small intestine and 30% for the colon, and even more at the anastomotic sites especially at ROI 1 and ROI 2, which is much more than the suggested 30%. Moreover, the clinical use of vasopressors to stabilize systemic blood pressure during sepsis, such as norepinephrine, has been shown to further compromise intestinal perfusion, aggravating the impaired healing in intestinal surgery[18].

While this study provides valuable insights into the effects of septic shock on intestinal microcirculation in general and around anastomoses, several limitations must be addressed. First, the study period of 150 minutes of E. coli infusion may not capture the long-term effects of sepsis on anastomotic healing. Future studies with extended experimental durations are necessary to better understand the progression of microcirculatory impairment and its impact on surgical outcomes.

Another limitation is the use of a porcine model. While pigs are a translationally relevant model for studying human intestinal microcirculation, their sepsis pathophysiology may not fully replicate the complex clinical scenarios encoun

The sample size of ten pigs also represents a limitation, as a larger cohort could reduce the risk of type II errors and potentially yield more statistically significant results. However, ethical considerations place constraints on animal research, and future studies must continue to balance the need for statistical power with ethical responsibility.

Beyond addressing these limitations, future research should investigate potential therapeutic interventions, such as targeted vasodilators, to preserve intestinal microcirculation during sepsis. These approaches may provide novel strategies to improve surgical outcomes and reduce complications, such as AL.

Moreover, the potential clinical applications of LSCI warrant further exploration. LSCI offers a unique capability for real-time, quantitative assessment of microcirculation, making it a promising tool for intraoperative decision-making in septic patients. For instance, its use could help surgeons evaluate the viability of intestinal segments before performing an anastomosis, minimizing the risk of ischemia-related complications. By integrating advanced imaging modalities like LSCI into acute surgical settings, clinicians may be able to enhance decision-making and improve patient outcomes in high-risk scenarios.

The findings of this study contribute meaningfully to the growing body of research on sepsis-related microcirculatory dysfunction by providing direct evidence of impaired perfusion in both untouched and anastomotic intestinal tissue during septic shock. While previous experimental models have assessed intestinal perfusion using alternative imaging modalities or non-standardized sepsis models, our use of LSCI in a reproducible porcine setup allows for precise, repeated, and clinically relevant assessment of real-time microcirculatory dynamics. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare perfusion differences between hand-sewn and stapled anastomoses under septic conditions. These insights are especially relevant in the context of emergency intestinal surgery, where surgeons often must decide between forming a primary anastomosis or diverting. By demonstrating how sepsis drastically reduces perfusion - particularly at the anastomotic site - our study provides a physiological basis for more cautious surgical decision-making and underscores the need for intraoperative tools that can guide anastomotic safety in high-risk patients.

This study highlights the impact of septic shock in intestinal microcirculation, revealing differences between untouched and anastomotic regions, as well as between small and large intestine. Also, hand-sewn anastomoses preserve microcirculation better than stapled ones, but both show a drastic decline, underscoring the significant risk of AL in septic patients. These findings provide a basis for optimizing surgical strategies and improving outcomes in a state of sepsis.

AU Foulum is acknowledged for its invaluable aid and supervision during experiments. Special gratitude is extended to animal caretaker Birgitte Frydkjær for her assistance during the operations. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Department of Medical Microbiology, Aarhus University Hospital, for their invaluable support in the preparation and handling of E. coli.

| 1. | Shepherd AP, Pawlik W, Mailman D, Burks TF, Jacobson ED. Effects of vasoconstrictors on intestinal vascular resistance and oxygen extraction. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Reilly PM, Wilkins KB, Fuh KC, Haglund U, Bulkley GB. The mesenteric hemodynamic response to circulatory shock: an overview. Shock. 2001;15:329-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | De Backer D, Hajjar L, Monnet X. Vasoconstriction in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50:459-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cao M, Wang G, Xie J. Immune dysregulation in sepsis: experiences, lessons and perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Deitch EA, Kemper AC, Specian RD, Berg RD. A study of the relationship among survival, gut-origin sepsis, and bacterial translocation in a model of systemic inflammation. J Trauma. 1992;32:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ruokonen E, Takala J, Kari A, Saxén H, Mertsola J, Hansen EJ. Regional blood flow and oxygen transport in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1296-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fink MP. Adequacy of gut oxygenation in endotoxemia and sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:S4-S8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Raia L, Zafrani L. Endothelial Activation and Microcirculatory Disorders in Sepsis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:907992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang X, Liu D. Hemodynamic Influences on Mesenteric Blood Flow in Shock Conditions. Am J Med Sci. 2021;362:243-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patel S, Duncan A. Anaesthesia and intestinal anastomosis. BJA Educ. 2021;21:433-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huisman DE, Bootsma BT, Ingwersen EW, Reudink M, Slooter GD, Stens J, Daams F; LekCheck Study group. Fluid management and vasopressor use during colorectal surgery: the search for the optimal balance. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:6062-6070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fischer PE, Nunn AM, Wormer BA, Christmas AB, Gibeault LA, Green JM, Sing RF. Vasopressor use after initial damage control laparotomy increases risk for anastomotic disruption in the management of destructive colon injuries. Am J Surg. 2013;206:900-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pranskunas A, Pilvinis V, Dambrauskas Z, Rasimaviciute R, Planciuniene R, Dobozinskas P, Veikutis V, Vaitkaitis D, Boerma EC. Early course of microcirculatory perfusion in eye and digestive tract during hypodynamic sepsis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krejci V, Hiltebrand LB, Sigurdsson GH. Effects of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and phenylephrine on microcirculatory blood flow in the gastrointestinal tract in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1456-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hiltebrand LB, Krejci V, tenHoevel ME, Banic A, Sigurdsson GH. Redistribution of microcirculatory blood flow within the intestinal wall during sepsis and general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:658-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Heeman W, Dijkstra K, Hoff C, Koopal S, Pierie JP, Bouma H, Boerma EC. Application of laser speckle contrast imaging in laparoscopic surgery. Biomed Opt Express. 2019;10:2010-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heeman W, Steenbergen W, van Dam G, Boerma EC. Clinical applications of laser speckle contrast imaging: a review. J Biomed Opt. 2019;24:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Paramasivam R, Kristensen NM, Ambrus R, Stavsetra M, Ørntoft MB, Madsen AH. Laser speckle contrast imaging for intraoperative assessment of intestinal microcirculation in normo- and hypovolemic circulation in a porcine model. Eur Surg Res. 2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dehring DJ, Crocker SH, Wismar BL, Steinberg SM, Lowery BD, Cloutier CT. Comparison of live bacteria infusions in a porcine model of acute respiratory failure. J Surg Res. 1983;34:151-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saeger HD, Kersting S, Vogelbach P, Hamel C, Oertli D, Hölscher A, Thomas WE. [Course system of the Working Group for Gastro-intestinal Surgery Davos]. Chirurg. 2010;81:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Russell KW, O'Holleran BP, Bowen ME, Mone MC, Scaife CL. The Barcelona Technique for Ileostomy Reversal. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:2269-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ambrus R, Strandby RB, Svendsen LB, Achiam MP, Steffensen JF, Søndergaard Svendsen MB. Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging for Monitoring Changes in Microvascular Blood Flow. Eur Surg Res. 2016;56:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jarczak D, Kluge S, Nierhaus A. Sepsis-Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Concepts. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:628302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tsai YY, Chen WT. Management of anastomotic leakage after rectal surgery: a review article. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:1229-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kashiwagi H. The lower limit of tissue blood flow for safe colonic anastomosis: an experimental study using laser Doppler velocimetry. Surg Today. 1993;23:430-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/