Published online Sep 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.107605

Revised: June 20, 2025

Accepted: July 29, 2025

Published online: September 27, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 24 Hours

Gastrointestinal surgery has disadvantages such as long operation time, extended hospitalization time, and slow postoperative recovery. However, the promotion and clinical application of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) concept have considerably shortened the hospitalization time of gastrointestinal surgery patients and reduced reactions to surgical stress and the risk of medical complications and readmission. ERAS breaks the conventional operating mode in the field of surgery but introduces great challenges in practice.

To explore the application of ERAS in perioperative patients within the field of gastrointestinal surgery, with a particular focus on investigating the awareness of ERAS among healthcare professionals and the barriers to its implementation.

A retrospective study of medical records of perioperative patients in the gastrointestinal surgery ward of Ningbo No. 2 Hospital from March 2020 to March 2022 was conducted. According to the different nursing modes adopted by patients during the perioperative period, patients were divided into the ERAS group and the control group. The postoperative outcomes of these groups such as the time to first ambulation, the time to first intake of food, and nursing sa

Compared with the control group, the ERAS group demonstrated superior scores across various metrics, with the exception of the readmission rate due to complications within 1 month post-discharge (P < 0.05). Statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of educational background, years of service, and prior training in ERAS (P < 0.05).

ERAS significantly reduces the time to first ambulation and first food intake for patients undergoing gas

Core Tip: Data of 115 gastrointestinal surgery patients were analyzed. Patients were divided into the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) group and the control group according to different nursing modes. The postoperative outcomes of these patients, such as recovery status and medical expense indicators, were compared. A self-designed questionnaire survey was used to evaluate the cognitive level of medical staff toward ERAS and the factors that hinder the implementation of ERAS. ERAS significantly shortened the time for patients to move out of bed for the first time and eat for the first time after surgery. The understanding of ERAS among medical stuff is related to their education level, work experience, and ERAS training experience.

- Citation: Fu XJ, Ren JX, Yuan LL, Hong Y. Application of enhanced recovery after surgery techniques in gastrointestinal surgery patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(9): 107605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i9/107605.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.107605

The concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) was first introduced by professor Kehlet[1] in Denmark in 1997, this innovative therapeutic approach aimed to expedite postoperative recovery for surgical patients. Utilizing a multimodal perioperative care strategy, professor Kehlet enabled patients undergoing elective colorectal resection to be discharged only 2 days post-surgery[2]. In recent years, ERAS has been widely adopted in multicenter clinical practices, which demonstrates its clinical safety and practicality in the management of gastric and colorectal cancers.

ERAS represents a novel pathway in surgical management, which focuses on optimizing various aspects of perioperative care, including health education, preoperative preparation, and postoperative mobilization. These measures are designed to minimize responses to surgical stress and promote recovery of patients[3]. The implementation of ERAS has been proven effective in conserving healthcare resources. ERAS significantly reduces surgical duration and average length of hospital stay for gastrointestinal surgery patients while also decreasing the incidence of postoperative complications and the need for conversion to open surgery. This approach facilitates rapid restoration of physiological functions, minimizes psychological trauma, alleviates pain, and accelerates the recovery process[4,5].

For hospitals, the reduction in patient length of stay and improved outcomes contribute to enhanced patient experiences and satisfaction[6]. Furthermore, with patients returning to work more promptly, ERAS generates substantial social benefits by conserving labor time. Research indicates that several perioperative measures within the ERAS framework yield significant patient benefits despite conflicting with traditional surgical practices[7,8]. Clinicians face numerous challenges in implementing these new protocols due to the absence of standardized industry guidelines. These issues are particularly evident in the current tense healthcare environment in China, where breaking away from conventional treatment modalities poses major obstacles for the adoption of ERAS[9].

Ningbo No. 2 Hospital, which is located in the city center, is a tertiary comprehensive public hospital with 16 specialized surgical departments, including hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, breast, thyroid, orthopedic, and vascular surgery. The hospital treats various complex cases, particularly in gastrointestinal surgery, which has the highest volume of single-disease types among clinical departments. The increasing prevalence of an aging population and multiple comorbidities complicates case management, which leads to challenges in cost control due to expanding expenditure beyond set limits. In early 2020, the hospital initiated the promotion of accelerated recovery management across its surgical departments. The gastrointestinal surgery department performed approximately 400 surgeries annually, with an average hospital stay of 11.6 days. From May 2020 to March 2022, a total of 53 gastric cancer patients underwent the full clinical pathway based on ERAS. By contrast, only 18.7% of other surgical departments implemented the complete ERAS protocol, while 56.3% engaged in partial components of the accelerated ERAS process, which indicates significant barriers to its broader implementation.

In summary, four factors related to ERAS - consensus guidelines, administrative management, healthcare personnel, and patient considerations - impact adherence to ERAS protocols. This study aims to investigate the awareness levels of gastrointestinal surgical staff regarding ERAS and the relevant influencing factors. In addition, it seeks to assess the current state of ERAS application in gastrointestinal surgery and explore the obstacles to its implementation. The findings will provide strategies to promote the clinical adoption of ERAS and offer valuable insights for policy formulation regarding its implementation.

A retrospective study of medical records of perioperative patients in the gastrointestinal surgery ward of Ningbo No. 2 Hospital between March 2020 and March 2022 was conducted. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) Aged between 18 and 80 years; (2) Undergoing elective gastric resection (partial or total, via open or laparoscopic approach); and (3) No prior history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Presence of obstruction, perforation, or hemorrhage; (2) Severe malnutrition, with a Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment score of C; (3) Diagnosis of cancer at other sites; and (4) Prior gastrointestinal surgery or impaired function of the heart, brain, liver, or kidneys. According to the different nursing modes adopted by patients during the perioperative period, they were divided into the ERAS group and the control group. A total of 115 perioperative patients from the gastrointestinal surgery department were involved in this study, with 62 patients in the control group and 53 patients in the ERAS group.

The inclusion criteria for healthcare personnel were as follows: Possession of a nursing or medical practitioner license issued by the ministry of National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China and at least 1 year of experience in gastrointestinal surgery. The exclusion criteria included absence from work due to maternity leave, illness, or other reasons. This study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningbo No. 2 Hospital and obtained informed consent from the patients.

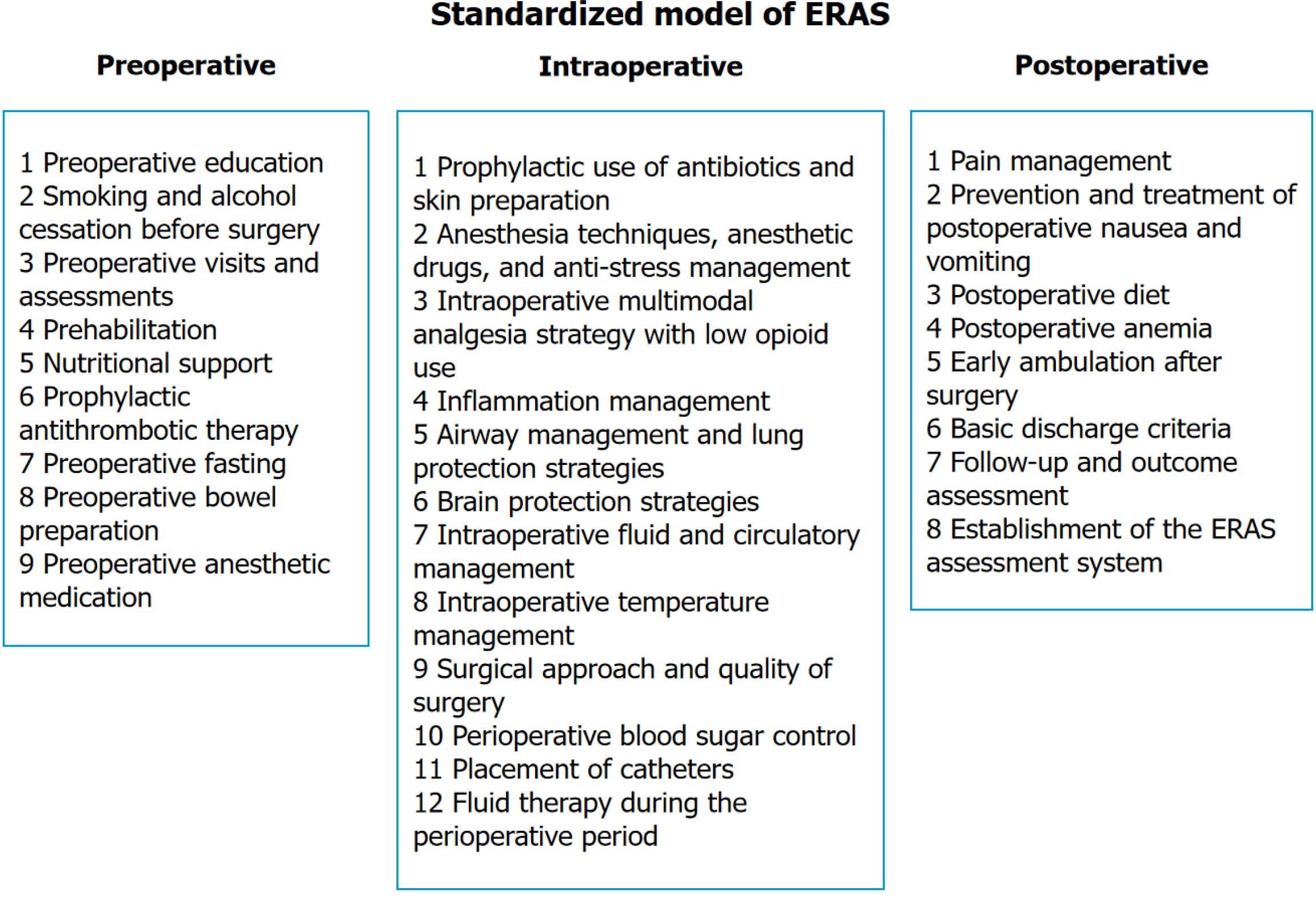

Intervention methods: The control group received standard gastrointestinal surgical care, while the ERAS group adopted an integrated management and service model constructed in March 2020, which optimized organizational structure and integrated perioperative services. This model was divided into three phases: Preoperative, intraoperative, and post

Evaluation indicators: The evaluation indicators for patients included the following: (1) A general information questionnaire covering various items, such as age, gender, and educational level; and (2) Postoperative outcomes, including time to first ambulation, time to first feeding, and duration of abdominal drainage tube placement. The evaluation indicators for healthcare personnel were as follows: (1) A general information questionnaire detailing educational level, years of service, and ERAS training experience; (2) A self-developed knowledge questionnaire for ERAS encompassing 30 items regarding the concept, process, and significance of ERAS. It was scored on a scale of 1, with total scores ranging from 0 to 30, where higher scores indicated greater understanding of ERAS, as well as a threshold of 20 distinguishing high and low levels of awareness; and (3) A self-developed survey for barrier factors of ERAS consisting of 9 items, with responses scored as 3 for agreement, 2 for neutrality, and 1 for disagreement.

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 24.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and independent sample t-tests were utilized to compare differences between groups. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages, with χ2 tests employed to assess intergroup differences. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The postoperative outcomes between the two groups were compared, including time to first ambulation, time to first feeding, duration of urinary catheter placement, length of hospital stay, and total hospitalization costs. The results indicated that, except for the readmission rate within one month due to complications, the ERAS group demonstrated significantly better outcomes across all measured parameters than the traditional control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| ERAS group (n = 53) | Control group (n = 62) | t | P value | |

| Time to first ambulation post-surgery (days) | 1.21 | 3.18 | 19.64 | < 0.05a |

| Time to first feeding post-surgery (days) | 1.65 | 5.38 | 19.09 | < 0.05a |

| Duration of abdominal drain placement post-surgery (days) | 4.29 | 5.04 | 3.67 | < 0.05a |

| Duration of urinary catheter placement post-surgery (days) | 1.38 | 2.28 | 8.14 | < 0.05a |

| Length of hospital stay post-surgery (days) | 6.90 | 10.28 | 9.13 | < 0.05a |

| Total hospitalization cost (in ten thousand yuan) | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.02 | < 0.05a |

| Readmission rate (%) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 0.202 | 0.653 |

This study utilized the case records from the ERAS demonstration unit for patients undergoing radical surgery for gastric cancer, along with billing system data and performance evaluation metrics from tertiary public hospitals. In this analysis, the proportion of medical service revenue was selected as the primary outcome measure. This revenue includes income from surgical procedures, treatments, and bed occupancy, excluding medications, diagnostic tests, and laboratory fees (Table 2). The analysis focuses on the impact of accelerated recovery on income structure and cost control within the pilot unit. In the ERAS group, the average medical service income per hospitalization was 15936.72 yuan, which reflected an increase of 8.67% compared with the previous period. The average surgical cost per hospitalization was 9613.80 yuan, which showed a growth of 6.70%. Conversely, the average nursing cost per hospitalization was 1266.68 yuan, which decreased by 0.11%. The average bed fee per hospitalization was 712.65 yuan, which marked a significant reduction of 22.6%. In addition, the average non-medical service income per hospitalization was 30508.67 yuan, which reduced by 11.23%. The average medication cost per hospitalization was 6917.35 yuan, which decreased by 11.91%. Meanwhile, the average consumable cost per hospitalization was 17383.43 yuan, which showed a decline of 9.63%.

| Control group (yuan) | ERAS group (yuan) | Growth (%) | |

| Average cost per hospitalization | 49232 | 46372 | -5.81% |

| Average medical service income per hospitalization | 14665.32 | 15936.72 | 8.67% |

| Average surgical cost per hospitalization | 9010.35 | 9613.8 | 6.70% |

| Average treatment cost per hospitalization | 1986.28 | 2118.14 | 6.64% |

| Average nursing cost per hospitalization | 1268.65 | 1266.68 | -0.11% |

| Average bed fee per hospitalization | 920.75 | 712.65 | -22.6% |

| Average non-medical service income per hospitalization | 34369.82 | 30508.67 | -11.23% |

| Average medication cost per hospitalization | 8719.95 | 6917.35 | -20.67% |

| Average consumable cost per hospitalization | 19236.87 | 17383.43 | -9.63% |

| Average examination cost per hospitalization | 2753.63 | 1955.18 | -29.00% |

| Average laboratory cost per hospitalization | 3589.14 | 3216.62 | -10.38% |

The nursing satisfaction of patients in the ERAS group was 94.34%, while that of patients in the control group was 77.42%. The nursing satisfaction of the ERAS group was significantly higher than that of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.011), as shown in Table 3.

| Very satisfied | Basically satisfied | Dissatisfied | Overall satisfaction | |

| ERAS group (n = 53) | 29 (54.72) | 21 (39.62) | 3 (5.66) | 50 (94.34) |

| Control group (n = 62) | 21 (33.87) | 27 (43.55) | 14 (22.58) | 48 (77.42) |

| χ2 | 6.494 | |||

| P value | 0.011 |

A total of 43 questionnaires were distributed and returned, which achieved a 100% response rate. All questionnaires were completed without omissions, which resulted in 42 valid responses, with a valid response rate of 97.7%. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in the awareness of ERAS among healthcare personnel based on educational background, years of experience, and ERAS training (P < 0.05) (Table 4). The barriers to the implementation of ERAS are summarized in Table 5.

| High (n) | Low (n) | χ2/t | P value | |

| Occupation | 1.433 | 0.231 | ||

| Doctor | 9 | 11 | ||

| Nurse | 6 | 16 | ||

| Education | 9.091 | 0.028 | ||

| Doctor | 1 | 0 | ||

| Master | 10 | 8 | ||

| Bachelor | 4 | 14 | ||

| Junior college | 0 | 5 | ||

| Working period | 12.435 | 0.001 | ||

| ≥ 10 years | 9 | 8 | ||

| 5-10 years | 4 | 8 | ||

| ≤ 5 years | 2 | 11 | ||

| ERAS training | 8.849 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 7 | ||

| No | 4 | 20 | ||

| Title | 1.167 | 0.558 | ||

| Senior | 5 | 7 | ||

| Intermediate | 7 | 17 | ||

| Junior | 3 | 3 |

| Factors | Agree | Neutrality | Disagree |

| The safety and efficacy of accelerated recovery require further validation | 36 | 4 | 2 |

| Multidisciplinary collaboration is lacking within the hospital | 22 | 5 | 15 |

| Implementation is primarily driven by physicians, with other personnel playing supportive roles | 16 | 10 | 16 |

| Deeply ingrained traditional beliefs causes difficulty for healthcare staff to change their perspectives in the short term | 32 | 5 | 5 |

| Variability in individual patient conditions complicates the uniform application of accelerated recovery protocols | 37 | 3 | 2 |

| Concerns on postoperative complications may lead to disputes between patients and healthcare providers | 31 | 10 | 1 |

| Patients may struggle to effectively understand and cooperate with the accelerated recovery process | 26 | 9 | 7 |

| Policy support for the advancement of ERAS is insufficient | 8 | 11 | 23 |

The ERAS project management team is led by the medical quality management department under the authorization of the hospital leadership, which comprises department heads from gastrointestinal surgery, respiratory medicine, anesthesia, nutrition, rehabilitation, and other relevant fields, as well as leaders from the medical quality management department, nursing department, medical affairs department, and operating room. This structure ensures effective interdepartmental communication, coordination, and the implementation of process improvements. Professionals from the rehabilitation and nutrition departments are stationed in the wards to provide specialized services and participate in daily ward rounds and preoperative assessments.

The medical quality management department analyzes the operational status of the ward and identifies issues, which helps organize discussions and formulate targeted solutions to establish an integrated management model of “clinical + administrative + medical technology”. Based on expert consensus and management guidelines in the ERAS field, the hospital has formed an expert group for in-depth discussions and developed an ERAS management framework and standardized operational procedures tailored to the characteristics of the hospital. Emphasis is placed on minimally invasive surgical techniques and individualized anesthesia plans, with particular attention to preoperative nutritional interventions, exercise status, prehabilitation measures, intraoperative airway management and lung protection strategies, and postoperative early rehabilitation training with one-on-one guidance. The aim is to establish a stan

Previous studies have demonstrated that ERAS significantly reduces postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, readmission rates, and mortality in patients undergoing gastric cancer surgery compared with traditional approaches[10]. Tanaka et al[11] randomized 148 patients post-gastric cancer surgery into the ERAS observation group and the conventional control group. In the current study, after implementing ERAS integrated management for gastrointestinal surgery patients, the ERAS group showed better activity time, feeding time, indwelling catheterization days, postoperative hospitalization days, and total hospitalization costs than the traditional control group, which is consistent with the results of literature research. The ERAS integrated management model has improved the quality of medical services, promoted patient recovery, and reduced the economic burden of hospitalization for patients. In addition, the shortened length of hospital stay after surgery means an increase in bed turnover and utilization, which leads to an improvement in hospital economic efficiency. Therefore, ERAS has played a crucial role in promoting clinical outcomes and economic efficiency during the perioperative period by innovating the mode of medical services.

Since January 2021, the hospital has implemented single-disease medical insurance settlement in line with healthcare reform models to control medical costs. The “disease-based settlement” approach aims to reform the medical payment system, which stimulates internal management within healthcare institutions to achieve cost control. However, in gastrointestinal surgery, the aging patient population and the prevalence of multiple comorbidities complicate the situation, with clinical departments facing the highest number of single-disease cases and increased complexity. Reports indicate that the application of ERAS pathways can significantly reduce postoperative hospital stay by up to 30%, which lowers medical costs[12]. In 2018, a reported that the implementation of ERAS for gynecological oncology surgery resulted in a net cost savings per patient was $956 (95% confidence interval: $162 to $1636)[13]. These results align closely with those of our study, which suggests that the integrated management model of ERAS enhances the quality and efficiency of medical services, optimizes the revenue structure of healthcare institutions, increases medical service income, and reduces unnecessary medical expenditures. Thus, the model supports the sustainable development of healthcare facilities.

In this study, the average surgical cost increased by 6.70% year-on-year. Meanwhile, the average hospitalization, nursing, and drug costs decreased by 5.81%, 0.11%, and 11.91% year-on-year, respectively. These findings are consistent with the results in the literature. The reduction in hospitalization costs is attributed to not only the shortening of hospitalization days but also the maintenance of the physiological functions of patients, which directly reduces the costs of conventional drug treatment and nutritional support. The integrated management model for ERAS improves the quality and efficiency of medical services, which optimizes the income structure of medical institutions, increases medical service revenue, reduces unnecessary medical expenses, and enhances the efficiency of nursing work. All these factors provide support for the sustainable development of medical institutions. In addition, the national performance evaluation criteria for tertiary public hospitals require hospitals to adjust their medical income structure for effectively reflecting the technical service value of medical workers. Therefore, implementing the comprehensive management strategy for ERAS is in line with the policy orientation of public hospitals to control rising costs. Such application also highlights the importance of the technical service value of medical workers.

Gastrointestinal surgical staff generally perceive numerous factors as obstacles to the promotion of ERAS. The primary barriers identified in our study are discussed as follows: 88.1% of healthcare personnel believe that the specific condition of each patient varies, which makes ERAS unsuitable for all clinical departments, 85.7% express concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of accelerated recovery, 76.2% feel that the initiative relies heavily on physicians, with other personnel playing supportive roles, 61.9% worry on potential postoperative complications leading to disputes between patients and healthcare providers, and 52.4% believe that the hospital lacks a multidisciplinary collaborative team.

These perceptions are related to that the optimization measures adopted during the perioperative period under ERAS often conflict with traditional practices. For instance, surgeons commonly express concerns regarding the safety of allowing patients to consume sugar-containing beverages 2 hours before surgery, the unconventional approach to bowel preparation before abdominal surgery, the early removal of abdominal drainage tubes postoperatively, and the early withdrawal of gastrointestinal decompression tubes. Surgeons fear that these practices may lead to complications such as vomiting, anastomotic leaks, intra-abdominal bleeding, or infection[14]. These long-standing traditional beliefs regarding surgical safety are difficult to alter in the short term, which indicates that the ERAS concept requires further ad

Failure in continuous involvement may result in insufficient comprehension and even misconceptions, which complicates the promotion of its application. While the hospital has established a multidisciplinary team to advance the implementation of ERAS, the operations of the team remain rooted in traditional consultation systems. In particular, these systems lack seamless interdepartmental coordination and the necessary management protocols and processes related to ERAS. This situation results in poor communication among disciplines during the perioperative period and challenges in coordinating various stages of care. As the number of patients included in the ERAS management group increases, the workload for the multidisciplinary team also escalates, which hinders the successful implementation of ERAS. Research indicates that timely adjustments based on feedback data can shorten hospitalization times and reduce the incidence of complications[15]. However, the absence of a sustained monitoring and feedback mechanism after 3 to 6 years of successful ERAS implementation emerges as a key factor undermining its clinical efficacy[16]. In terms of quality control management, the hospital lacks an information system to monitor and provide feedback throughout the ERAS process. Healthcare personnel implementing standardized clinical pathways based on ERAS often lack an evidence-based clinical mindset. Instead, they adhere rigidly to recommended measures without sufficient application, which undermines the clinical effectiveness of ERAS and raises concerns regarding postoperative complications and disputes with patients.

Factors such as the educational background, years of experience, and ERAS training of healthcare personnel significantly influence their awareness of ERAS. Our study results indicate that healthcare professionals with higher educational qualifications demonstrate a significantly greater understanding of ERAS than their lower-educated counterparts. This result may be attributed to the greater opportunities for academic engagement and exposure to ERAS-related knowledge among highly educated staff, who also possess more clinical experience and professional competence. Conversely, lower-educated personnel have fewer opportunities to engage with cutting-edge concepts and knowledge, which affects their understanding of ERAS.

Healthcare professionals with 10 or more years of experience exhibit a markedly higher awareness of ERAS than those with fewer than 10 years of experience. This finding is likely due to the former group having a more substantial knowledge base and clinical experience, which enables them to think critically on solutions when encountering challenges, as well as having more avenues to access new knowledge and ideas[17]. By contrast, less experienced staff tend to focus more on learning emergency response capabilities due to their limited experience. Our findings suggest that professional training is an independent factor influencing the awareness of ERAS among gastrointestinal surgical staff. Most healthcare personnel have limited opportunities for external exchanges, training, and further education. As a result, they have narrow channels for acquiring new knowledge and concepts.

This study has certain limitations. First, this study is a single-center, small-scale retrospective study. Only including gastrointestinal surgery patients and medical staff from a large tertiary hospital cannot represent the implementation of ERAS among surgical patients and the knowledge, attitude, and behavior of ERAS among medical staff in other hospitals. Undoubtedly, a certain degree of selection bias exists. Large scale, multicenter, and prospective studies will be needed in the future to validate the credibility of the results of this study. Second, in terms of medical safety, further observation and research are needed for serious complications after surgery. In the future, we plan to continue exploring the application effect of ERAS in perioperative patients of gastrointestinal surgery in a multicenter, large-scale prospective study.

Compared with traditional nursing models, the implementation of ERAS provides significant advantages in reducing the time to first postoperative ambulation and the time to first intake of food for gastrointestinal surgery patients. Thus, ERAS plays a crucial role in accelerating patient recovery. However, the overall awareness of ERAS among healthcare professionals remains relatively low. Their awareness of ERAS is closely linked to their educational background, years of experience, and prior ERAS training.

| 1. | Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in RCA: 1817] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Bai S, Wu Q, Wu W, Song L. Discussion on the influence of optimizing the perioperative management on the recovery after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e36396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Demirpolat MT, Şişik A, Yildirak MK, Basak F. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Promotes Recovery in Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang L, Zhang T, Wang K, Chang B, Fu D, Chen X. Postoperative Multimodal Analgesia Strategy for Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Elderly Colorectal Cancer Patients. Pain Ther. 2024;13:745-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan L, Peng D, Cheng Y. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Is Still Powerful for Colorectal Cancer Patients in COVID-19 Era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fernandez S, Trombert-Paviot B, Raia-Barjat T, Chauleur C. Impact of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program in gynecologic oncology and patient satisfaction. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2023;52:102528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | He JJ, Geng L, Wang ZY, Zheng SS. Enhanced recovery after surgery in perioperative period of liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:594-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cossu G, Belouaer A, Kloeckner J, Caliman C, Agri F, Daniel RT, Gaudet JG, Papadakis GE, Messerer M. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol for the perioperative management of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors/pituitary adenomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2023;55:E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Band IC, Yenicay AO, Montemurno TD, Chan JS, Ogden AT. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol in Minimally Invasive Lumbar Fusion Surgery Reduces Length of Hospital Stay and Inpatient Narcotic Use. World Neurosurg X. 2022;14:100120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sugisawa N, Tokunaga M, Makuuchi R, Miki Y, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. A phase II study of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in gastric cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:961-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tanaka R, Lee SW, Kawai M, Tashiro K, Kawashima S, Kagota S, Honda K, Uchiyama K. Protocol for enhanced recovery after surgery improves short-term outcomes for patients with gastric cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:861-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sauro KM, Smith C, Ibadin S, Thomas A, Ganshorn H, Bakunda L, Bajgain B, Bisch SP, Nelson G. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Guidelines and Hospital Length of Stay, Readmission, Complications, and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2417310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bisch SP, Wells T, Gramlich L, Faris P, Wang X, Tran DT, Thanh NX, Glaze S, Chu P, Ghatage P, Nation J, Capstick V, Steed H, Sabourin J, Nelson G. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in gynecologic oncology: System-wide implementation and audit leads to improved value and patient outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shao YR, Ke X, Luo LH, Xu JD, Xu LQ. Application of early enteral nutrition nursing based on enhanced recovery after surgery theory in patients with digestive surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:1910-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fair LC, Leeds SG, Whitfield EP, Bokhari SH, Rasmussen ML, Hasan SS, Davis DG, Arnold DT, Ogola GO, Ward MA. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol in Bariatric Surgery Leads to Decreased Complications and Shorter Length of Stay. Obes Surg. 2023;33:743-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tazreean R, Nelson G, Twomey R. Early mobilization in enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: current evidence and recent advancements. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gramlich LM, Sheppard CE, Wasylak T, Gilmour LE, Ljungqvist O, Basualdo-Hammond C, Nelson G. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: a strategy to transform surgical care across a health system. Implement Sci. 2017;12:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/