Published online Sep 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.106543

Revised: May 13, 2025

Accepted: July 28, 2025

Published online: September 27, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 0.2 Hours

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the primary treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis. Although rapid recovery nursing is commonly implemented in post

To analyze the impact of rapid recovery nursing in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis undergoing LC.

A retrospective study was conducted with a total of 120 patients with acute calculous cholecystitis who underwent LC at our hospital between October 2023 and October 2024. The patients were divided into two groups with 60 patients in each group according to the different nursing methods: Conventional nursing and rapid recovery nursing groups. Data was recorded from the electronic medical records. Gastrointestinal recovery, pain, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction were compared between the two groups before and after nursing.

Following nursing intervention, the visual analog scale scores on Days 3 and 7 post-surgery in the rapid recovery nursing group were notably lower than those of the conventional nursing group (P < 0.05). The rapid recovery nursing group experienced significantly reduced times for bowel sound recovery, getting out of bed, hospital stay, passing flatus, and first defecation compared with the conventional nursing group (P < 0.05), thereby experiencing significantly better quality of life and nursing satisfaction (P < 0.05).

Rapid recovery nursing effectively promoted the recovery of gastrointestinal function, reducing pain and im

Core Tip: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the primary treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis. Although rapid recovery nursing is frequently used in postoperative care, its impact on patients undergoing this procedure remains unclear. Analyzing its effects revealed its benefits such as enhanced gastrointestinal function, reduced postoperative pain, and improved overall quality of life.

- Citation: Chen ZY, Han XD, Liu M, Fu MY, Nie YJ, Wang FE. Effects of rapid recovery nursing after surgery in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(9): 106543

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i9/106543.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.106543

Acute calculous cholecystitis is a common condition categorized under acute abdomen with approximately 80% of cases resulting from gallstones. Patients typically present with severe colic, abdominal distension, nausea, and vomiting. Without timely intervention disease progression can lead to high fever and jaundice, significantly impacting patient quality of life[1]. Recent data indicated an increasing incidence of acute cholecystitis in China with epidemiological studies showing that 10%-15% of individuals suffer from bile duct stones and 1%-3% experience acute cholecystitis or cholangitis annually. If left untreated, then infections may escalate to septic shock, multiple organ failure, and sepsis. Currently, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the primary treatment for acute calculous cholecystitis[2,3]. However, postoperative challenges such as pain and decreased quality of life remain significant concerns[4,5].

Conventional postoperative care primarily focuses on bed rest and lacks structured intervention strategies, often resulting in prolonged recovery times and higher complication rates[6]. In recent years rapid recovery nursing has emerged as an approach to optimize perioperative management and promote early rehabilitation. The enhanced recovery after surgery model includes parameters such as preoperative education, optimized anesthesia techniques, early postoperative feeding, effective pain management, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Currently, rapid recovery nursing is widely used in various surgical procedures. Kehlet and Wilmore[7] noted that recovery nursing can shorten hospital stays and improve patient rehabilitation while Istrate et al[8] showed that it effectively relieved postoperative pain in patients undergoing LC and accelerated gastrointestinal recovery.

Despite its widespread application in postoperative care, the benefits of rapid recovery nursing for patients with acute calculous cholecystitis remain unclear[9-11]. Studies have shown that rapid recovery nursing significantly reduces the hospitalization duration for patients undergoing laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, but further research is needed to assess its impact on the postoperative quality of life and recovery[12]. Thus, exploring its effects on gas

In this study we aimed to evaluate the effect of fast-track recovery care on gastrointestinal function, pain management, and overall quality of life in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis undergoing LC.

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed clinical data from 120 patients with acute cholecystitis who underwent LC at our hospital between October 2023 and October 2024. Based on the nursing methods recorded in electronic medical records, patients were divided into two groups with 60 patients in each: Rapid recovery nursing and conventional nursing. To minimize bias both patients and outcome evaluators remained blinded.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients classified as grade III acute cholecystitis based on the Tokyo guidelines at the time of admission[13,14]; (2) Patients with stable vital signs and good mental status; and (3) Patients without contraindications for laparoscopic surgery, capable of tolerating general anesthesia and pneumoperitoneum.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with severe visceral dysfunction; (2) Patients with coagulation disorders, gastrointestinal dysfunction, or immune/metabolic abnormalities that could affect surgical outcomes; (3) Patients with systemic infections, gallbladder perforation, or necrosis; (4) Patients with malignant tumors or other acute abdominal conditions; and (5) Patients with incomplete clinical data.

This study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee. Owing to its retrospective nature, informed consent was waived.

Conventional nursing group: Patients’ vital signs were monitored, analgesics were administered based on individual pain levels, and dressings were changed regularly, ensuring wounds remained clean and dry to minimize infection risk. Additionally, patients were advised to avoid overeating after surgery. Wound healing and overall recovery were systematically evaluated.

Rapid recovery nursing group: Rapid recovery nursing incorporated the following measures in addition to conventional care: (1) Preoperative evaluation. Assessing the patient’s overall health status and developing a personalized care plan; (2) Teamwork. Coordination among surgical specialists, nurses, and rehabilitation experts to optimize patient care; (3) Pain management. Implementing multimodal analgesia, including class I analgesics, local anesthesia, or nerve blocks, to ensure effective pain control while minimizing opioid use; (4) Early mobilization. Encouraging patients to start moving early, ideally within 6-24 h postoperatively, to prevent deep-vein thrombosis and enhance gastrointestinal function; (5) Infection control. Ensuring proper wound care and the rational use of antibiotics to minimize the risk of infection; (6) Rehabilitation planning. Developing personalized rehabilitation regimens that include progressive physical activity and breathing exercises; (7) Dietary management. Providing digestible, nutrient-rich foods, starting with liquids 6 h post-surgery, progressing to semi-liquid, and transitioning to a regular diet as intestinal function recovers; (8) Education and family support. Offering health education to patients and families, including postoperative care instructions, dietary recommendations, and medication management; (9) Regular follow-ups. Conducting regular postoperative follow-ups to monitor the recovery process and promptly address any concerns; and (10) Psychological support. Providing mental health assistance to ensure emotional well-being throughout recovery.

Gastrointestinal function recovery: Included postoperative bowel sounds, flatulence, defecation, time to first meal, and hospital stay duration.

Pain assessment: Pain levels were assessed at baseline and on postoperative days 1, 3, and 7 using the visual analog scale (0-10) scores: (1) 0 (no pain); (2) 1-3 (mild pain, does not interfere with sleep); (3) 4-6 (moderate pain); and (4) 7-10 (severe pain, disrupts sleep)[15].

Quality of life assessment: The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) was assessed across four domains: Physical; psychological; social; and environmental. Scores ranged up to 100 with higher scores indicating better quality of life[16].

Postoperative complications: Included surgical site infection, intestinal and bile leakage, and gastrointestinal reactions.

Nursing satisfaction: Scored via a self-developed questionnaire: (1) < 60 (dissatisfied; minimal perceived improvement in psychological state, comfort, or pain); (2) 60-85 (basic satisfaction; some positive impact observed); and (3) > 85 (very satisfied; significant improvement noted). The overall satisfaction rate was calculated as follows: [(number of “basic satisfaction” + “satisfied” cases)/total cases] × 100%[17].

Data analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics for Windows (version 26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and were compared using the independent t-test to assess statistical significance. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages

The study included 60 patients with 30 males (50%) in the rapid recovery nursing group. Their average age was 45.0 ± 10.0 years, the average body mass index (BMI) was 21.23 ± 3.05 kg/m², and the average duration of illness was 9.45 ± 0.64 h. The conventional nursing group included 28 males (46.7%) with an average age of 46.0 ± 11.0 years, an average BMI of 21.26 ± 3.24 kg/m², and an average illness duration of 9.51 ± 0.70 h. Other demographic details are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found in baseline characteristics between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Index | Rapid recovery nursing group (n = 60) | Conventional nursing group (n = 60) | P value |

| Age (years) | 45.0 ± 10.0 | 46.0 ± 11.0 | 0.132 |

| Gender | Male: 30 (50.00) | Male: 28 (46.70) | 0.418 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.23 ± 3.05 | 21.26 ± 3.24 | 0.735 |

| Mean duration of disease (hours) | 9.45 ± 0.64 | 9.51 ± 0.70 | 0.964 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists status | 0.637 | ||

| I | 28 (46.67) | 25 (41.67) | |

| II | 22 (36.67) | 24 (40.00) | |

| III | 10 (16.67) | 11 (18.33) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 10 (16.70) | 12 (20.00) | 0.163 |

| Diabetes | 8 (13.30) | 7 (11.70) | 0.216 |

| Surgical method | LC | LC | |

| Blood routine | |||

| WBC count (109/L) | 9.0 ± 3.1 | 9.2 ± 2.9 | 0.578 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.4 ± 1.4 | 0.746 |

| Biochemical panel | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 40.0 ± 12.0 | 42.0 ± 10.0 | 0.837 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 35.0 ± 11.0 | 36.0 ± 10.0 | 0.792 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 18.0 ± 5.0 | 19.0 ± 6.0 | 0.653 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 85.0 ± 15.0 | 87.0 ± 13.0 | 0.362 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 43.0 ± 4.0 | 42.0 ± 3.0 | 0.281 |

| Smoking history (n) | 0.182 | ||

| Yes | 16 (26.70) | 18 (30.00) | |

| No | 44 (73.30) | 42 (70.00) | |

| Drinking history (n) | 0.173 | ||

| Yes | 20 (33.30) | 22 (36.70) | |

| No | 40 (66.70) | 38 (63.30) |

Following nursing interventions, the rapid recovery nursing group demonstrated significantly shorter times to bowel sound recovery, flatus passage, first bowel movement, and first feeding compared with the conventional nursing group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the time to first ambulation post-surgery was significantly reduced in the rapid recovery nursing group (P < 0.05). These results are summarized in Table 2.

| Index | Conventional nursing group (n = 60) | Rapid recovery nursing group (n = 60) |

| Time to first eating (hours) | 45.38 ± 5.63 | 32.15 ± 6.01 |

| Defecation time (hours) | 55.38 ± 11.03 | 41.15 ± 9.46 |

| Bowel sound recovery time (hours) | 47.71 ± 10.27 | 28.86 ± 8.46 |

| First anal exhaust time (hours) | 49.91 ± 8.53 | 39.14 ± 9.51 |

| Time to first ambulation (day) | 3.27 ± 1.62 | 2.16 ± 1.03 |

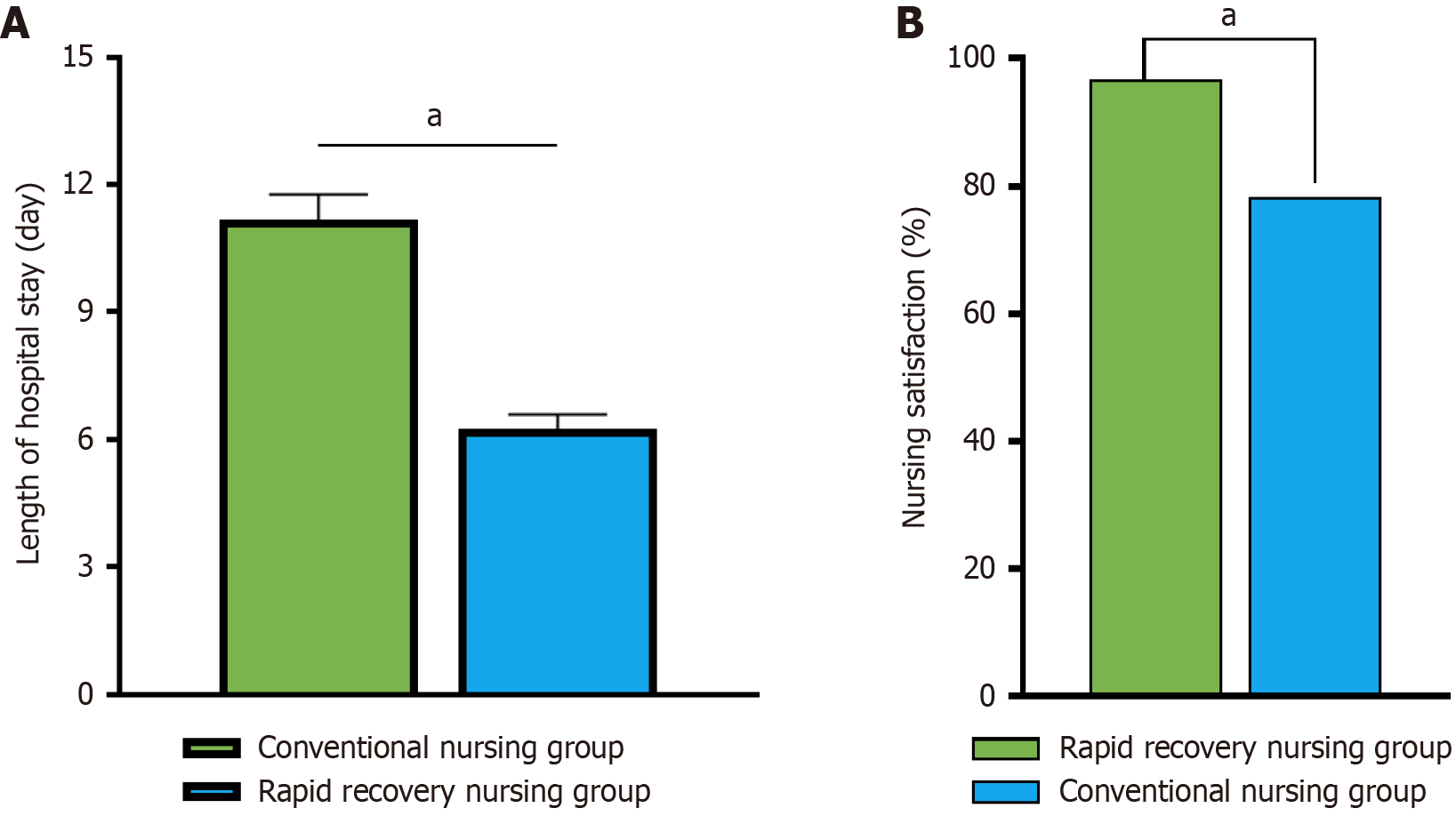

The rapid recovery nursing group had a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay (6.24 ± 0.35 days) compared with the conventional nursing group (11.16 ± 0.61 days) with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). A comparison is shown in Figure 1A.

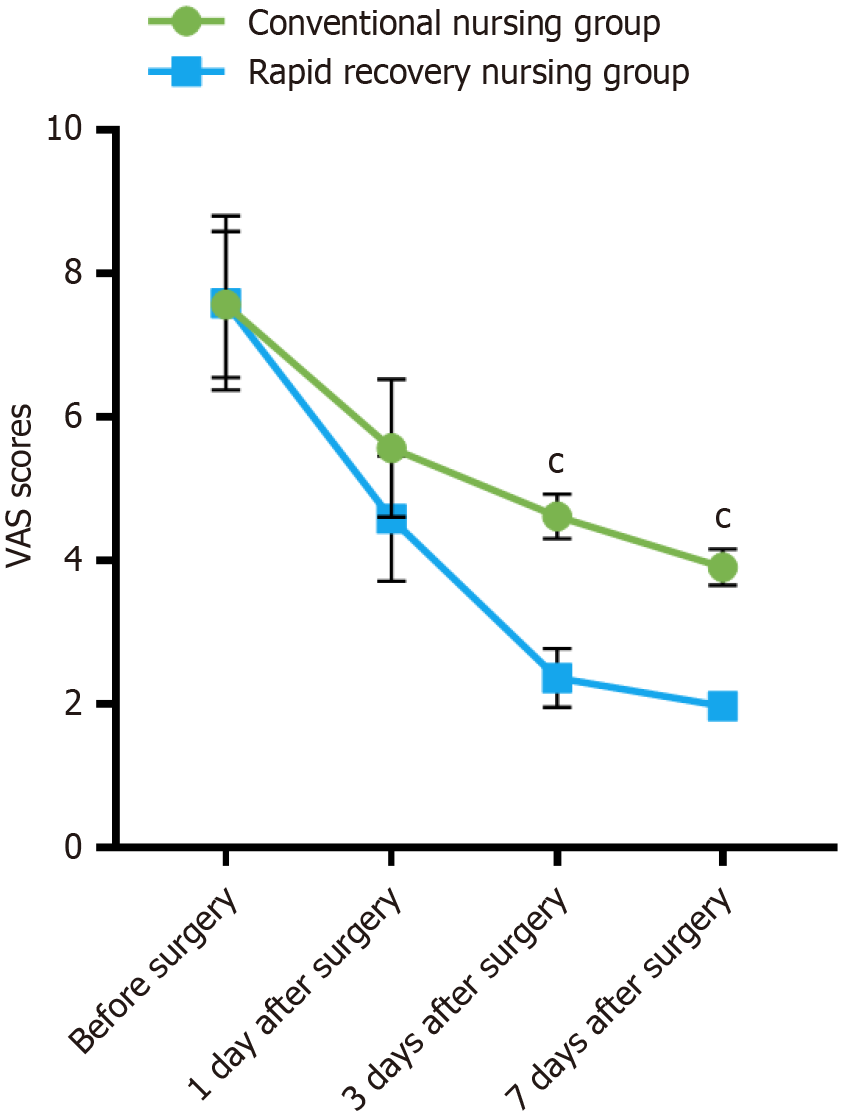

Preoperatively, pain scores were comparable between the rapid recovery nursing group (7.59 ± 1.21) and the conventional nursing group (7.57 ± 1.02), showing no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). However, the postoperative pain scores on day 1 (4.59 ± 0.87), day 3 (2.37 ± 0.41), and day 7 (1.98 ± 0.17) in the rapid recovery nursing group were all significantly lower than those in the conventional nursing group (5.57 ± 0.96, 4.62 ± 0.31, and 3.91 ± 0.25, respectively) with statistically significant differences (P < 0.001). The results are shown in Figure 2.

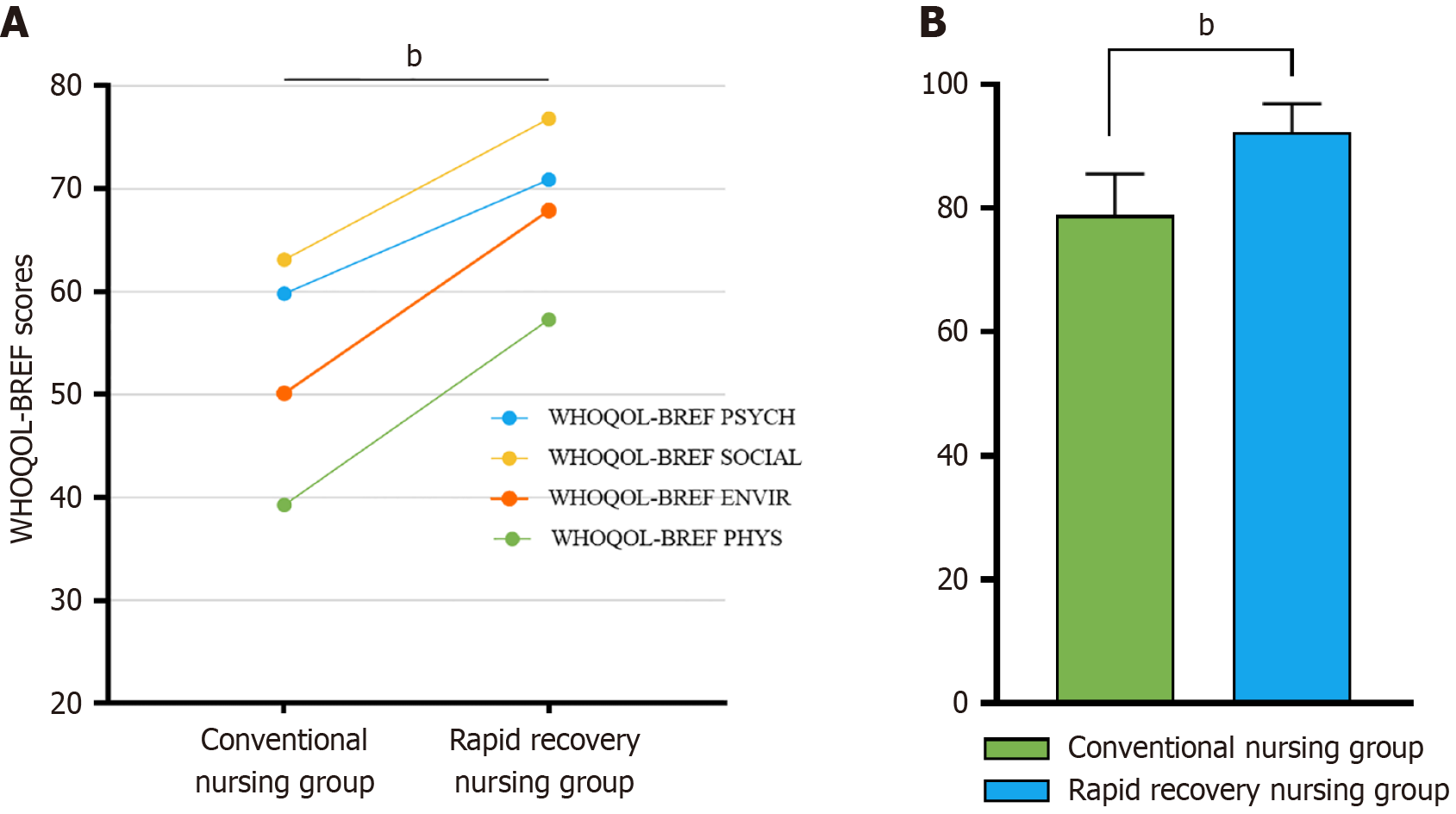

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in quality of life between the two groups as assessed using the WHOQOL-BREF. The conventional nursing group reported mean scores of 39.27 ± 3.58 in the physical health domain, 59.82 ± 6.73 in the psychological domain, 63.1 ± 6.01 in the social relationship domain, and 50.13 ± 5.36 in the environmental domain. In contrast the rapid recovery nursing group demonstrated significantly higher scores across all subdomains and in the total WHOQOL-BREF score (P < 0.01), indicating an improved quality of life.

Following nursing interventions, postoperative complications were significantly lower in the rapid recovery nursing group (5.0%, 3/60) as compared with the conventional nursing group (18.3%, 11/60) (P < 0.01). These results are summarized in Table 3.

| Group | Conventional nursing group (n = 60) | Rapid recovery nursing group (n = 60) | P value |

| Surgical site infection | 5 (8.3) | 1 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal leakage | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Bile leakage | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal reaction | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Total incidence | 11 (18.3) | 3 (5.0) |

The nursing satisfaction rate in the rapid recovery nursing group was 96.7% (58/60), significantly higher than the 78.3% (47/60) observed in the conventional nursing group (P < 0.05; Figure 1B).

The rapid recovery nursing model facilitates postoperative recovery and enhances clinical results through evidence-based medical methods. It has been successfully applied across various surgical procedures[18], promoting gastrointestinal function recovery, accelerating overall rehabilitation, and lowering complication risks[19]. Research indicates that enhanced recovery care for patients undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy can significantly reduce intraoperative blood loss, shorten hospital stays, and lower the incidence of bladder irritation[20].

Compared with the conventional nursing group, patients in the rapid recovery nursing group exhibited significantly shorter recovery times for gastrointestinal function, first bowel movement, and dietary intake (P < 0.05). Additionally, the time to first ambulation and the overall hospital stay were significantly shorter in the rapid recovery nursing group (P < 0.05) while pain scores on postoperative days 3 and 7 were significantly lower compared with the conventional nursing group (P < 0.05). These findings are consistent with previous research results[20,21].

The results of this study indicated that the WHOQOL-BREF scores in the rapid recovery nursing group were significantly higher than those in the conventional nursing group (P < 0.01). This aligns with previous research de

Additionally, this study indicated that postoperative complications occurred in 5.0% of patients in the rapid recovery nursing group and was significantly lower than the 18.3% observed in the conventional nursing group (P < 0.01). Furthermore, the nursing satisfaction rate in the rapid recovery nursing group was 96.7% (58/60), notably higher than that of the conventional nursing group (78.3%; 47/60) (P < 0.05). These results align with previous research findings[24,25]. Several factors may impact these results. First, patient-related variables such as age, underlying conditions (such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease), and BMI may impact the outcomes. Second, regardless of the nursing model, older patients or those with preexisting conditions may recover slowly. Third, patient compliance to the rapid recovery nursing program, including early mobilization and dietary adjustments, may vary, affecting the effectiveness of the intervention. Finally, hospital-specific and surgical team-related factors may also play a role. Consequently, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, satisfaction with care was assessed using a self-developed questionnaire for which validity and reliability data are unavailable, limiting the credibility of this result.

Additionally, future studies should explore strategies to optimize rapid recovery nursing implementation, address adherence barriers, and assess cost-effectiveness across diverse healthcare environments. The rapid recovery nursing protocol itself has inherent limitations. For example, while early postoperative feeding is a core component, some patients may experience nausea or vomiting, necessitating temporary cessation of oral intake. Additionally, aggressive opioid-based pain management can sometimes lead to constipation, contradicting the goal of promoting gastrointestinal recovery. Multidisciplinary cooperation, another key aspect of rapid recovery nursing, requires significant coordination and communication among team members and may not be feasible in all healthcare settings. Additionally, future studies should explore strategies to optimize rapid recovery nursing implementation, address adherence barriers, and assess cost-effectiveness in diverse healthcare environments. Such investigations will build upon the findings of this study and further refine the understanding of rapid recovery nursing in the management acute calculous cholecystitis.

This study had certain limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective cohort study, all patients were treated at the same institution. Consequently, the findings may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings with different surgical techniques, nursing protocols, or patient demographics, and selection bias may affect result extrapolation. Additionally, the expertise and experience of the surgical and nursing teams in implementing rapid recovery nursing protocols at our institution may have influenced outcomes, potentially overestimating the effectiveness in settings with less specialized staff. Second, this study relied on clinical electronic medical record data, which may introduce recall bias and has inherent limitations in data availability and accuracy. Notably, data on patient adherence to rapid recovery nursing components, such as early mobilization and dietary intake, were not systematically collected, potentially confounding the association between protocol implementation and outcomes.

Third, the relatively small sample size of 60 patients per group may affect the generalizability of the study results. Fourth, this study did not employ a standardized complication grading system (such as the Clavien-Dindo classification) or calculate the comprehensive complication index, which limits in-depth analysis of complication severity and cumulative burden. Although differences in complication rates were statistically significant, the low absolute number of events (1-5 cases per group) increases the risk of false-positive results, necessitating cautious interpretation. Future studies should incorporate standardized grading systems and the CCI for a more comprehensive and objective safety assessment.

Moreover, the study was underpowered to detect rare complications or subtle differences in long-term outcomes between groups. Finally, long-term outcomes, such as symptom recurrence or new-onset complications, were not considered. Future research should extend follow-up periods and conduct large-scale, prospective, multicenter studies to further evaluate the sustained benefits of rapid recovery nursing for patients with acute calculous cholecystitis undergoing LC.

This study demonstrated that compared with conventional nursing the rapid recovery nursing model for patients undergoing LC for acute calculous cholecystitis enhanced gastrointestinal function recovery, improved quality of life, reduced postoperative pain and complication rates, and increased nursing satisfaction. Therefore, integrating rapid recovery nursing protocols into clinical practice is recommended with close monitoring of complications tailored to individual patient needs.

| 1. | Jin X, Jiang Y, Tang J. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Transhepatic Gallbladder Drainage Improves the Prognosis of Patients with Severe Acute Cholecystitis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:5045869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Glasgow RE, Cho M, Hutter MM, Mulvihill SJ. The spectrum and cost of complicated gallstone disease in California. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1021-5; discussion 1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kortram K, van Ramshorst B, Bollen TL, Besselink MG, Gouma DJ, Karsten T, Kruyt PM, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Kelder JC, Tromp E, Boerma D. Acute cholecystitis in high risk surgical patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CHOCOLATE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loozen CS, van Santvoort HC, van Geloven AAW, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, de Reuver PR, Besselink MHG, Vlaminckx B, Kelder JC, Knibbe CAJ, Boerma D. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in the treatment of acute cholecystitis (PEANUTS II trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang L, Zheng R, Li H, Ren Y, Chen H. The burden of appendicitis and surgical site infection of appendectomy worldwide. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023;17:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liang J, Wang L, Song J, Zhao Y, Zhang K, Zhang X, Hu C, Tian D. The impact of nursing interventions on the rehabilitation outcome of patients after lumbar spine surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1147] [Cited by in RCA: 1236] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Istrate AM, Serban D, Doran H, Tudor C, Bobirca F, Davitoiu D, Dumitrescu D, Popescu A, Cherecheanu MP, Tanasescu C, Motofei I. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy - A Systematic Review. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2024;119:318-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Robella M, Tonello M, Berchialla P, Sciannameo V, Ilari Civit AM, Sommariva A, Sassaroli C, Di Giorgio A, Gelmini R, Ghirardi V, Roviello F, Carboni F, Lippolis PV, Kusamura S, Vaira M. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Program for Patients with Peritoneal Surface Malignancies Undergoing Cytoreductive Surgery with or without HIPEC: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | ERAS Compliance Group. The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Compliance on Elective Colorectal Cancer Resection: Results From an International Registry. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1153-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Wijk L, Udumyan R, Pache B, Altman AD, Williams LL, Elias KM, McGee J, Wells T, Gramlich L, Holcomb K, Achtari C, Ljungqvist O, Dowdy SC, Nelson G. International validation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society guidelines on enhanced recovery for gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:237.e1-237.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li G, Zhang J, Cai J, Yu Z, Xia Q, Ding W. Enhanced recovery after surgery in patients undergoing laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Ukai T, Endo I, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Pitt HA, Matsunaga N, Takamori Y, Umezawa A, Asai K, Suzuki K, Han HS, Hwang TL, Mori Y, Yoon YS, Huang WS, Belli G, Dervenis C, Yokoe M, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Jagannath P, Garden OJ, Miura F, de Santibañes E, Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Wada K, Honda G, Supe AN, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Gouma DJ, Deziel DJ, Liau KH, Chen MF, Liu KH, Su CH, Chan ACW, Yoon DS, Choi IS, Jonas E, Chen XP, Fan ST, Ker CG, Giménez ME, Kitano S, Inomata M, Mukai S, Higuchi R, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, Borzellino G, Cimbanassi S, Boerna D, Coccolini F, Tufo A, Di Martino M, Leung J, Sartelli M, Ceresoli M, Maier RV, Poiasina E, De Angelis N, Magnone S, Fugazzola P, Paolillo C, Coimbra R, Di Saverio S, De Simone B, Weber DG, Sakakushev BE, Lucianetti A, Kirkpatrick AW, Fraga GP, Wani I, Biffl WL, Chiara O, Abu-Zidan F, Moore EE, Leppäniemi A, Kluger Y, Catena F, Ansaloni L. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Budrovac D, Radoš I, Hnatešen D, Haršanji-Drenjančević I, Tot OK, Katić F, Lukić I, Škiljić S, Nešković N, Dimitrijević I. Effectiveness of Epidural Steroid Injection Depending on Discoradicular Contact: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:3672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kovačević I, Majerić Kogler V, Krikšić V, Ilić B, Friganović A, Ozimec Vulinec Š, Pavić J, Milošević M, Kovačević P, Petek D. Non-Medical Factors Associated with the Outcome of Treatment of Chronic Non-Malignant Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ye Y, Ge J. Clinical application of comfort nursing in elderly patients with advanced lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:9750-9756. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 2431] [Article Influence: 270.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang X, Li Y, Yang W. Rapid Rehabilitation Program Can Promote the Recovery of Gastrointestinal Function, Speed Up the Postoperative Rehabilitation Process, and Reduce the Incidence of Complications in Patients Undergoing Radical Gastrectomy. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1386382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Song R, Chen C, Shang L. Efficacy and Satisfaction Evaluation of Rapid Rehabilitation Nursing Intervention in Patients with Laparoscopic Myomectomy. J Oncol. 2022;2022:9412050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Qiu J, Li M. Nondrainage after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Acute Calculous Cholecystitis Does Not Increase the Postoperative Morbidity. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8436749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yin M, Yan Y, Fan Z, Fang N, Wan H, Mo W, Wu X. The efficacy of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) for elderly patients with intertrochanteric fractures who received surgery: study protocol for a randomized, blinded, controlled trial. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CH, Lassen K, Nygren J, Hausel J, Soop M, Andersen J, Kehlet H. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24:466-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1001] [Cited by in RCA: 1058] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Akhtar MS, Khan N, Qayyum A, Khan SZ. Cost difference of enhanced recovery after surgery pathway vs. Conventional care In Elective Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2020;32:470-475. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Gu YX, Wang XY, Chen Y, Shao JX, Ni SX, Zhang XM, Shao SY, Zhang Y, Hu WJ, Ma YY, Liu MY, Yu H. Optimizing surgical outcomes for elderly gallstone patients with a high body mass index using enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:2191-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/