Published online May 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.105410

Revised: February 25, 2025

Accepted: March 7, 2025

Published online: May 27, 2025

Processing time: 122 Days and 14.8 Hours

Gallstone pancreatitis is the leading cause of acute pancreatitis, accounting for more than 40% of cases. Etiological treatment is a critical issue in acute biliary pancreatitis as it helps reduce the risk of recurrence. Patients who have ex

Core Tip: Gallstone pancreatitis is the leading cause of acute pancreatitis, accounting for more than 40% of cases. Etiological treatment is a critical issue in acute biliary pancreatitis as it helps reduce the risk of recurrence. This review aims to determine the role and timing of cholecystectomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis in the general population. Special attention will also be given to the care of frail and elderly patients, a group frequently affected by this condition.

- Citation: Dupont B, Lozac'h J, Alves A. Etiological treatment of gallstone acute pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(5): 105410

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i5/105410.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.105410

Acute pancreatitis is a very common condition and is the leading cause of hospitalization for gastroenterological reasons in Western countries[1]. Traditionally, two clinical forms are distinguished: Mild to moderate forms, which are characterized by a benign abdominal presentation with favorable progression, typically requiring only a short hospitalization, and severe forms (about 20% of cases), defined by the presence of persistent organ failure or severe local complications such as infected pancreatic necrosis, which can have a poor prognosis. While the overall mortality rate for acute pancreatitis is less than 2%, it can range from 20% to 35% in severe cases, depending on the series[2,3].

The primary cause of acute pancreatitis is gallstone-related (about 40%), followed by alcohol-related causes (30%-40%)[4]. All other causes (metabolic, tumor-related, idiopathic, infectious, autoimmune, genetic, etc.) account for only 20% of cases.

Although the management of acute pancreatitis has significantly evolved over recent decades, with paradigm shifts in nutritional support and fluid resuscitation, the core of initial management remains symptomatic (fluid resuscitation, pain relief, monitoring, and organ failure support). Aside from nutritional management, no treatment has shown benefit on the natural history of the disease[5]. Therefore, addressing the underlying cause is a critical issue. In the case of gallstone pancreatitis, the underlying treatment is even more important, as it has been shown that patients treated for biliary acute pancreatitis (BAP) are at high risk for early recurrence. Approximately 9% to 30% of patients will experience a recurrence of pancreatitis within the first few weeks after the initial episode if cholecystectomy is not performed[6-8]. The severity of each episode of pancreatitis is unpredictable.

Cholecystectomy remains the treatment of choice for BAP. This review aims to detail its indications and, especially, the timing of its performance. We will also clarify the role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which may be useful in the management of stones in the main bile duct. Additionally, we will also include a section dedicated to the management of elderly or frail patients, who are commonly encountered in cases of BAP.

Articles included in this review were selected using the MEDLINE database with the following key words: Pancreatitis, Acute Pancreatitis, Gallstone Pancreatitis, Biliary Pancreatitis, Bile Duct Stone, Choledocholithiasis, ERCP, and Cholecystectomy. Selection was restricted to English-language articles indexed from the inception of the database up to November 4, 2024.

Two investigators (Dupont B and Lozac'h J) independently reviewed the database and screened the titles, abstracts, and full-text articles to select studies. The bibliographies of all selected full-text articles were manually searched to identify additional potentially relevant studies. We used the most recent meta-analyses and randomized trials on cholecystectomy or ERCP in BAP for this review. When the question was not addressed by a randomized trial, we referred to cohort studies or controlled retrospective studies. Case reports and uncontrolled retrospective studies were excluded. The studies included in this review are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

For this review, we distinguish the management for patients who have developed either a mild or a severe form of acute pancreatitis.

Severe forms refer to moderately severe and severe forms according to the Atlanta classification, that is, patients who have developed organ failure or a local or systemic complication[9]. Mild forms refer to patients who do not develop any of these complications.

In BAP, pancreatitis is caused by the migration of a gallstone into the bile duct, which becomes lodged at the level of the ampulla of Vater[10]. This leads to an obstruction of the main pancreatic duct and pancreatic excretion, and can also result in biliary reflux into the pancreatic ducts, causing damage to the gland. In most cases, this obstruction is transient, as the stone migrates spontaneously into the digestive tract[10]. Cholecystectomy helps prevent recurrence. It is easy to understand that the earlier the procedure is performed, the lower the risk of further biliary events. However, this benefit may be counterbalanced by the risk of complications or surgical difficulty when the surgery is performed during an acute pancreatitis episode, especially with possible local complications.

The timing of cholecystectomy has long been debated, but the latest literature data have greatly clarified the optimal timing for performing the procedure, at least in non-severe forms.

The PONCHO study from 2015 showed, in a randomized trial comparing 129 patients who underwent same-admission cholecystectomy to 137 patients who had delayed surgery, a benefit in favor of cholecystectomy performed during the same hospitalization[6]. Patients were included if they had mild to moderate BAP without local complications, meaning without necrosis. The main outcome, which was the rate of readmission for gallstone-related complications or death, showed a benefit: 5% vs 17%; P = 0.002, with a significant reduction in interval pancreatitis, without the surgery being more difficult (no increase in operative time or conversion rates, and no increase in perceived difficulty for the surgeon). These findings were confirmed by a 2019 meta-analysis of five randomized trials (629 patients), showing a reduction in biliary events (OR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.09-0.33)[11] and a 2022 meta-analysis of 11 trials (1176 patients), confirming a reduction in biliary events (RR = 0.10, 95%CI: 0.05-0.19) and recurrent pancreatitis (RR = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.09-0.51) without an increase in surgical complications[12]. Furthermore, the “same-admission cholecystectomy” strategy appears to be cost-effective[13].

Overall, it now seems accepted that in the case of non-necrotizing mild pancreatitis, cholecystectomy should be performed during the same hospitalization. However, the question of the optimal timing for surgery remains open. Several studies have compared early surgery (within 24 to 48 hours) to delayed surgery (beyond this period), showing no significant difference in complication rates but with a shorter hospital stay for early cholecystectomy[14-17]. A large United States national database study reviewed more than 142000 cases of mild BAP[18]. They compared the risk of major adverse events in 129251 patients who underwent cholecystectomy within the first two weeks, with those who had surgery within 2 days (25% of the population) vs after 2 days (74% of the population). The rate of major adverse events was higher in patients who underwent surgery after 2 days: OR = 1.4; 95%CI: 1.29-1.51. Overall, the rate of major adverse events or readmissions increased almost linearly in patients operated on after the 2-day delay[18]. However, new data seems necessary to assess the relevance of performing surgery within this timeframe, as this study did not provide information on the reasons behind the delay in intervention.

The precise timing of cholecystectomy remains difficult to define, as current tools for predicting the severity of pancreatitis are still modest and improvable[19,20]. It can be challenging to predict with certainty the severity of pancreatitis in all cases within 48 hours, especially since the decision to perform the surgery depends on the severity assessment. Several scoring systems (Ranson, BISAP, APACHE-II, CTSI) have been developed and evaluated in an attempt to predict the progression of acute pancreatitis to a severe form. However, these systems generally lack specificity in predicting disease progression and often provide only a late assessment, typically after at least 48 hours[19]. In such cases, the decision to perform surgery within the first 48 hours of treatment—when it depends on severity assessment—can be challenging.

Currently, the recommendation is to perform cholecystectomy during the same hospitalization for mild BAP. In real-world practice, however, few patients undergo surgery during the same hospitalization. A retrospective international cohort of more than 5000 patients showed a cholecystectomy rate of only 29% for this indication[21].

In severe forms of BAP, the optimal timing for performing cholecystectomy remains difficult to determine. The MANCTRA-1 cohort compiled data from over 5000 cases of BAP. Of these, 3696 patients underwent cholecystectomy, and among them, 378 had severe or moderately severe pancreatitis[22]. In this population, 71.4% underwent delayed cholecystectomy, while 28.6% had the procedure within the first two weeks. The post-cholecystectomy mortality and morbidity were significantly higher in the early cholecystectomy group: 15.5% vs 1.2% (P < 0.001) and 30.3% vs 10.3% (P < 0.001), respectively. However, this study has several limitations. Severe pancreatitis accounted for only 7.4% of the population, and the reason for cholecystectomy was unknown. The surgery may have been performed for other reasons, particularly for managing complications, with cholecystectomy performed at the same time. This could have led to the selection of a more severe group of patients in the early cholecystectomy cohort.

A 2022 Dutch multicenter study examined the outcomes of 248 patients who were candidates for cholecystectomy due to severe BAP[7]. The risk of interval events was lower when cholecystectomy was performed within 10 weeks (RR = 0.49; 95%CI: 0.27-0.90; P = 0.02), compared with the risk of pancreatitis when the intervention was performed within eight weeks (RR = 0.14; 95%CI: 0.02-0.99; P = 0.02). Additionally, there was no increase in the complication rate of cho

To date, there is no definitive timeframe for performing cholecystectomy in severe forms of BAP. One could consider performing the procedure later, after eight weeks or after the regression of collections, as recommended by the Dutch experts.

The role of ERCP in BAP has long been debated. To clarify the relevance of this procedure, it is important to distinguish between emergencies, for which concrete answers have been provided in recent years, and "cold" situations.

The first question is whether there is a benefit to performing emergency ERCP in BAP, especially in cases of severe forms. A Dutch multicenter randomized study, the APEC study, addresses this question. Two hundred and thirty-two patients with BAP and severity criteria (APACHE II ≥ 8, Imrie ≥ 3, or C reactive protein > 150 mg/L) and no associated cholangitis were randomized to receive ERCP with sphincterotomy within 24 hours, compared to usual conservative treatment[23]. The primary endpoint was mortality or the occurrence of a major complication within six months. The rate of major complications or mortality was not significantly different between the two groups (38% vs 44%, P = 0.37), nor was the mortality rate or the occurrence of organ failure. This result remained true even in the subgroup of patients with jaundice.

Subsequently, the authors conducted a new study based on the conclusion that ERCP with sphincterotomy had been futile in a significant number of cases, where the stone in the main bile duct had migrated spontaneously between diagnosis and the procedure. They compiled data from a prospective multicenter cohort, again including patients with BAP and severity criteria but without associated cholangitis (as in the previous study). This cohort underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) first, and sphincterotomy was performed only if a stone in the main bile duct was confirmed[24]. This arm was compared to the conservative treatment arm from the previous study. The conclusions were identical, showing no benefit of urgent ERCP even in cases with confirmed bile duct stones (41% vs 44%, P = 0.65). While this study was not truly randomized, it remains the best evidence to date of the lack of benefit of emergency ERCP in BAP in the absence of associated cholangitis. However, in the case of cholangitis, this procedure is still indicated, as recommended by the 2018 Tokyo guidelines, with ERCP performed within 48 hours for mild to moderate cases and as soon as possible for severe grade III cases associated with organ failure[25]. It is important to emphasize that performing ERCP in the context of pancreatitis is a complex procedure. It should not be rushed and should ideally be performed by an experienced operator. A retrospective study from Korea involving 162 patients found that performing ERCP within 18 hours for cholangitis-associated BAP was associated with an increased risk of complications, including pneumonia and hypotension post-ERCP[26].

Although in most cases the stone responsible for BAP will migrate spontaneously, a stone can sometimes persist in the main bile duct. Therefore, the question arises about the management of this stone, either in parallel or in anticipation of cholecystectomy.

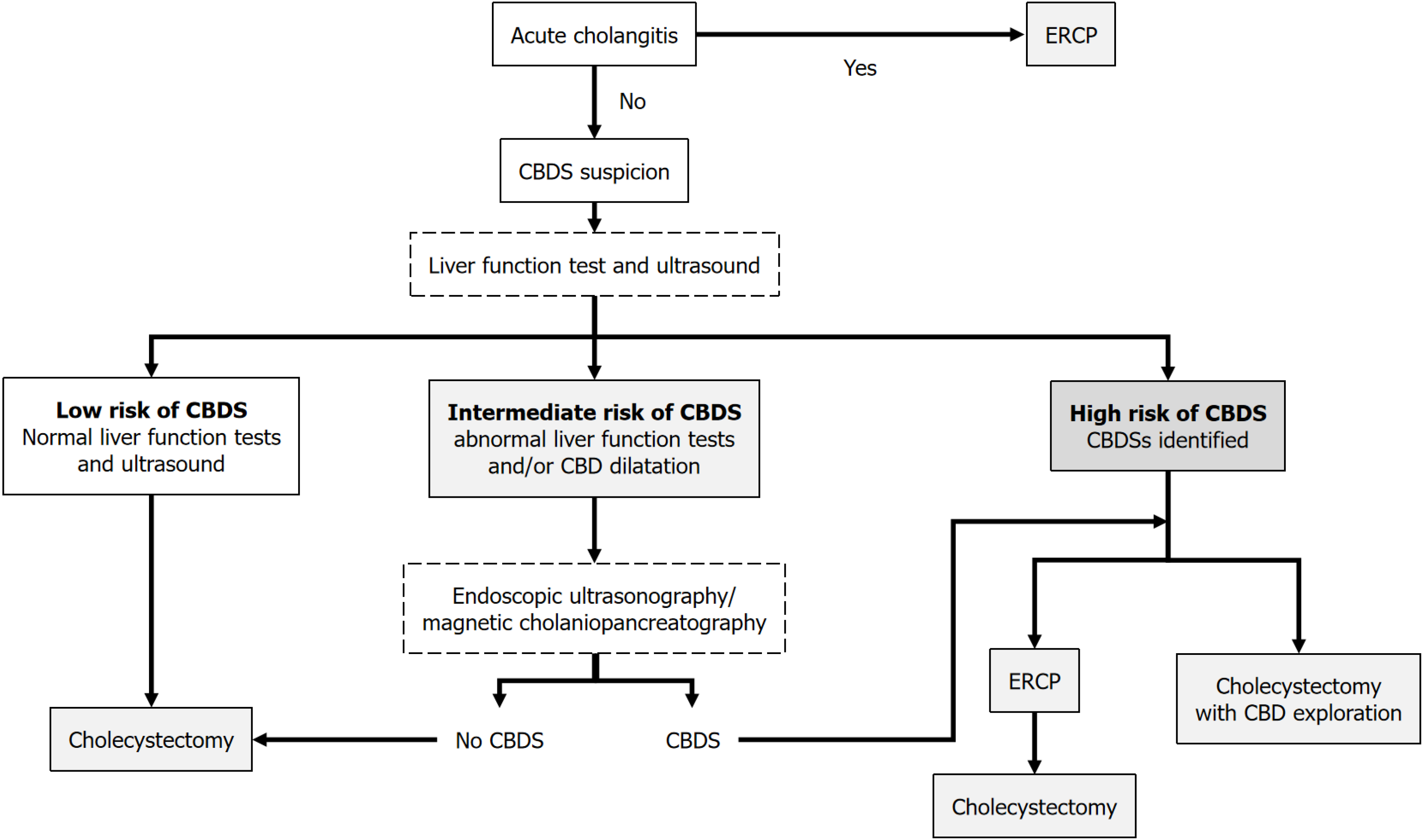

According to the ESGE guidelines, if the liver function tests have returned to normal and there is no confirmed stone in the bile duct or bile duct dilation on imaging, the presence of a stone in the main bile duct is unlikely, and chole

A Swiss randomized study conducted across five centers compared two approaches for patients at intermediate risk for a stone in the main bile duct, as defined previously: Either direct cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography, potentially combined with ERCP if necessary, or performing an MRI first, followed by ERCP if a stone is confirmed, and then cholecystectomy[30]. Notably, more stones were found in the intraoperative cholangiography group, and the overall length of hospitalization was shorter in this group. Although this study alone does not allow us to conclude the best strategy for managing a common bile duct stone when cholecystectomy is indicated, it highlights an important point. It seems reasonable to conclude that the tests used to identify a common bile duct stone (MRI or EUS) should not delay management, whether by ERCP or cholecystectomy, as doing so may increase the risk of interval biliary events.

The management of common bile duct stones in BAP is proposed in Figure 1.

When cholecystectomy cannot be performed due to the patient's condition or when it has already been carried out, there appears to be a proven benefit of sphincterotomy. A large American cohort study compiled data from over 150000 cases of BAP[31]. Patients who underwent ERCP alone (12% of the population) had fewer readmissions than those who had neither ERCP nor cholecystectomy [adjusted HR (aHR)= 0.8; 95%CI: 0.76-0.83; P < 0.0001]. These findings were also true for readmissions due to recurrent pancreatitis, both in the overall population (aHR = 0.51; 95%CI: 0.47-0.55; P < 0.0001) and in the subgroup of patients who had severe initial pancreatitis (aHR = 0.64; 95%CI: 0.54-0.75; P < 0.0001). Other studies have confirmed the protective effect particularly in the long term (after 1 or 2 years) of sphincterotomy in smaller retrospective cohorts[32,33]. Therefore, it seems well-established that in the absence of a cholecystectomy to be per

The more challenging question that remains to be answered in the management of BAP is the role of a possible interval sphincterotomy in patients who have had severe acute pancreatitis without any confirmed residual stone in the common bile duct, to prevent recurrence before the cholecystectomy, which will, by definition, be performed later. As previously noted, the risk of interval pancreatitis in patients with biliary pancreatitis is far from negligible, with a recurrence rate of 9% to 30% in the first few weeks, and it is impossible to predict the severity of the episode[6-8]. However, in cases of severe acute pancreatitis, cholecystectomy can only be performed, at best, after several weeks. The risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis must be weighed against the potential reduction in the risk of pancreatitis recurrence in the time period between the pancreatitis episode and the cholecystectomy, which is at least two months.

The risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis has remained stable at around 10%, despite advances in management, according to data from a meta-analysis compiling over 145 randomized trials from the past six years[34]. However, there is no reliable data regarding the reduction in the risk of pancreatitis after sphincterotomy during the interval between the pancreatitis episode and the cholecystectomy. In 4 studies comparing groups of patients with or without sphincterotomy (Table 1), a reduction in the rate of interval pancreatitis from 4% to 15% was observed. However, these data remain very limited and do not allow a definitive conclusion on the benefit of this procedure[6,31,32,35]. A study based on American data shows a relatively higher mortality in patients who did not undergo sphincterotomy compared to those who did, but these data are criticized, as they are from a generally non-severe population, with unclear indications for ERCP and no data on group comparability[36].

In cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis, the impact of this new episode on the progression of the initial pancreatitis remains unclear. It is uncertain whether the iatrogenic episode will influence the natural course of the initial condition, parti

Randomized trials on this issue will be necessary to determine the potential benefit of interval sphincterotomy in severe BAP. To date, this procedure does not seem to be subject to any specific recommendations.

Due to the high prevalence of lithiasis-related diseases among the elderly and the overall aging of the population, the management of BAP in elderly or frail patients is a frequent clinical scenario. It is also a particularly sensitive situation, as studies have shown that frail patients treated for BAP have higher rates of mortality and readmission compared to non-frail patients, along with significantly higher total hospitalization costs[38].

While cholecystectomy remains the gold standard for etiological treatment, as previously discussed, some frail patients may not be suitable candidates for this procedure. Frailty and advanced age are independent factors associated with higher mortality and complications after cholecystectomy, according to data from two meta-analyses[39,40]. Therefore, it is important to explore alternative treatment options for this patient population.

For frail patients with bile duct stones, performing endoscopic sphincterotomy alone, without cholecystectomy, is an alternative worth considering compared to the sequential approach of endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by cho

For patients without residual stones who are excluded from cholecystectomy or who have already undergone cholecystectomy, performing a protective sphincterotomy seems to offer significant benefits, as previously discussed. García de la Filia Molina et al[32] demonstrated in a population of elderly patients who were excluded from cho

In these complex situations, and more broadly, treatment decisions should be made in a multidisciplinary manner, carefully assessing the individual risks for each patient and selecting the most appropriate treatment based on the available literature and local practices.

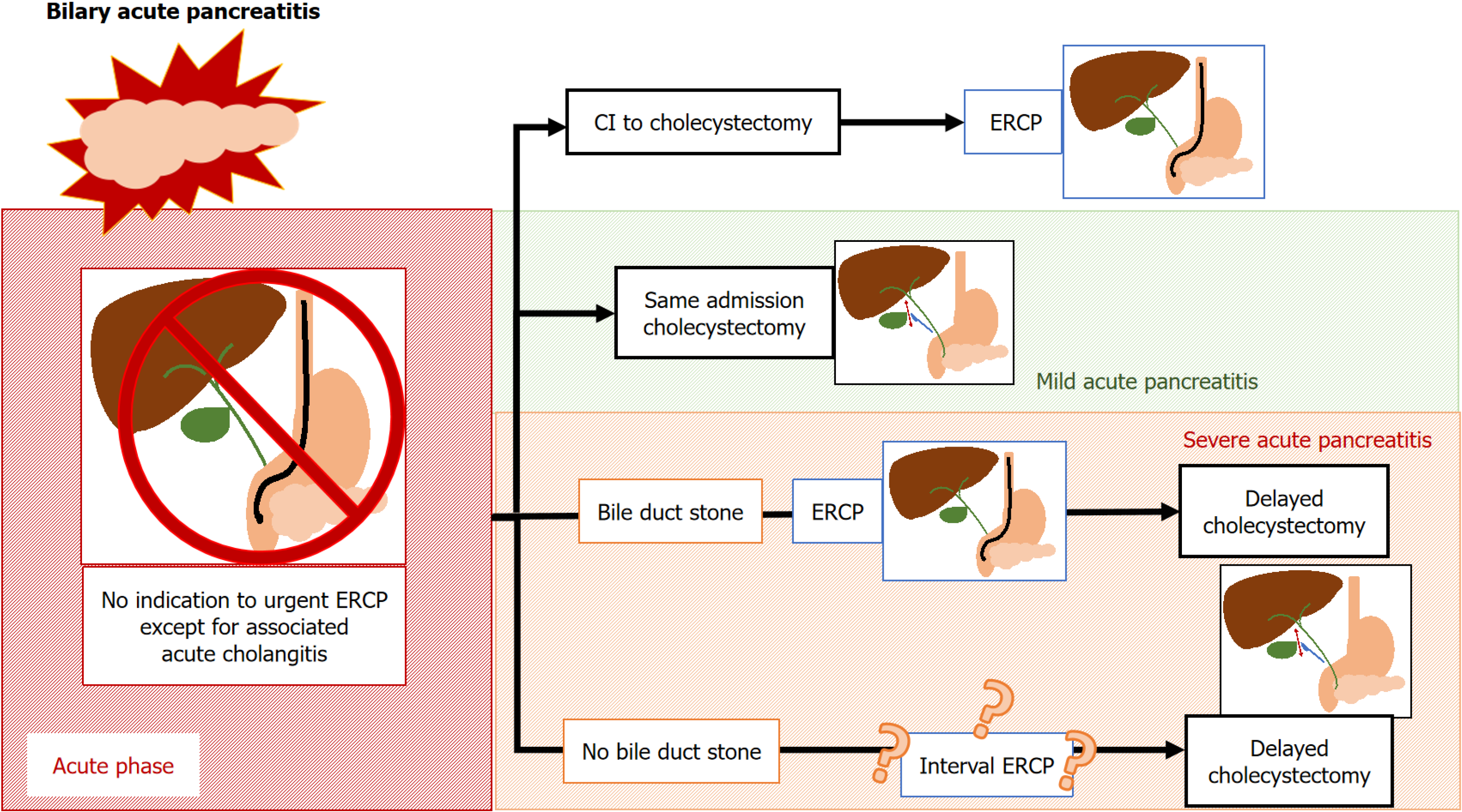

Considering all of these data, we propose the following etiological management for BAP which is summarized in Figure 2.

Urgent ERCP is not indicated in the absence of associated cholangitis[23,44].

In non-severe BAP, same-admission cholecystectomy should be performed[6,11].

In severe BAP, cholecystectomy should be performed later (after 8 weeks or once any collections have resolved)[7].

The presence of a stone in the common bile duct is most commonly treated with ERCP, but it can also be managed with a single surgical procedure in cases of non-severe BAP[45].

In the absence of a residual bile duct stone, there is no demonstrated benefit in performing a sphincterotomy to prevent a biliary interval event while awaiting cholecystectomy.

When the patient has already undergone cholecystectomy or when it is contraindicated, there is a benefit on the risk of biliary recurrence in performing a protective sphincterotomy, even if the stone responsible for the pancreatitis has spontaneously migrated[31,32].

While the management of BAP has been significantly clarified in recent years, several current conclusions on the management of BAP are based on observational or retrospective data, which are subject to numerous biases. In particular, several studies analyzing the timing of cholecystectomy in severe pancreatitis or the use of “protective sphincterotomy” do not provide insight into the reasons why clinicians chose to perform, delay or avoid these procedures.

Firstly, although it is well-established that cholecystectomy should be performed during the same hospitalization in patients with mild acute pancreatitis, the precise optimal timing for this procedure still needs to be determined. As previously discussed, obtaining a reliable assessment of pancreatitis severity before 72 hours remains a challenge. While the management of pancreatitis relies on estimated severity, current scoring systems can be improved[19]. New prognostic markers should be explored in the coming years.

In patients with severe acute pancreatitis, the ideal timing for cholecystectomy also needs further clarification. Randomized trials comparing different time frames for surgery should be conducted to assess the impact of timing on surgical complications and the expected benefits in terms of reducing biliary or pancreatic events. The presence or absence of organized collections and their locations may also be explored in specific studies, as these complications could influence surgical outcomes.

While awaiting surgery in patients with severe pancreatitis but without residual bile duct stone, the potential benefit of a protective sphincterotomy could be investigated in a randomized controlled trial. This study would evaluate its impact on biliary events, compared to the risks of recurrent pancreatitis, and its effect on the natural history of the initial episode. In patients who have undergone cholecystectomy or are contraindicated for the procedure, with no residual stones in the common bile duct, the benefit of protective sphincterotomy should also be investigated in a randomized study.

Lastly, the lack of benefit from sphincterotomy in patients with common bile duct stones identified by EUS, when compared to a watchful waiting approach, could be the subject of a true randomized trial. The APEC-2 study, was merely a trial comparing the strategy of EUS followed by ERCP if a common bile duct stone was identified and the control arm of the APEC-1 study.

In the future, the management of acute biliary pancreatitis is expected to evolve with technological advancements. Artificial intelligence could be utilized to enhance diagnostic tools, predict the severity of pancreatitis, and assist in making the most appropriate treatment decisions for patients. Additionally, further improvements in ERCP instruments and surgical techniques may make procedures less invasive and more effective, leading to improved management of complications.

The etiological treatment of BAP is crucial as it significantly impacts the natural history of the disease, drastically reducing the risk of recurrence. Cholecystectomy should be performed during the initial hospitalization in cases of benign BAP and at a later stage in severe forms. The optimal timing for this surgery, however, still needs to be clarified.

| 1. | Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Lund JL, Dellon ES, Williams JL, Jensen ET, Shaheen NJ, Barritt AS, Lieber SR, Kochar B, Barnes EL, Fan YC, Pate V, Galanko J, Baron TH, Sandler RS. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:254-272.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 776] [Cited by in RCA: 1122] [Article Influence: 160.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Verdonk RC, Boermeester MA, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:726-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 687] [Article Influence: 114.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jung B, Carr J, Chanques G, Cisse M, Perrigault PF, Savey A, Lefrant JY, Lepape A, Jaber S. [Severe and acute pancreatitis admitted in intensive care: a prospective epidemiological multiple centre study using CClin network database]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2011;30:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Forsmark CE, Vege SS, Wilcox CM. Acute Pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1972-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crockett SD, Wani S, Gardner TB, Falck-Ytter Y, Barkun AN; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1096-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 74.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | da Costa DW, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Boermeester MA, Bruno MJ, van Eijck CH, Timmer R, Weusten BL, Consten EC, Brink MA, Spanier BWM, Bilgen EJS, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Hofker HS, Rosman C, Voorburg AM, Bosscha K, van Duijvendijk P, Gerritsen JJ, Heisterkamp J, de Hingh IH, Witteman BJ, Kruyt PM, Scheepers JJ, Molenaar IQ, Schaapherder AF, Manusama ER, van der Waaij LA, van Unen J, Dijkgraaf MG, van Ramshorst B, Gooszen HG, Boerma D; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1261-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hallensleben ND, Timmerhuis HC, Hollemans RA, Pocornie S, van Grinsven J, van Brunschot S, Bakker OJ, van der Sluijs R, Schwartz MP, van Duijvendijk P, Römkens T, Stommel MWJ, Verdonk RC, Besselink MG, Bouwense SAW, Bollen TL, van Santvoort HC, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Optimal timing of cholecystectomy after necrotising biliary pancreatitis. Gut. 2022;71:974-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ito K, Ito H, Whang EE. Timing of cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis: do the data support current guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2164-2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4709] [Article Influence: 362.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 10. | Acosta JM, Ledesma CL. Gallstone migration as a cause of acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:484-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 439] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moody N, Adiamah A, Yanni F, Gomez D. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of early versus delayed cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2019;106:1442-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Prasanth J, Prasad M, Mahapatra SJ, Krishna A, Prakash O, Garg PK, Bansal VK. Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy for Acute Biliary Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg. 2022;46:1359-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | da Costa DW, Dijksman LM, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boerma D, Gooszen HG, Dijkgraaf MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Cost-effectiveness of same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy after mild gallstone pancreatitis in the PONCHO trial. Br J Surg. 2016;103:1695-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, Kaji AH, Putnam B, Neville A, Stabile BE, de Virgilio C. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kelly TR, Wagner DS. Gallstone pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial of the timing of surgery. Surgery. 1988;104:600-605. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mueck KM, Wei S, Pedroza C, Bernardi K, Jackson ML, Liang MK, Ko TC, Tyson JE, Kao LS. Gallstone Pancreatitis: Admission Versus Normal Cholecystectomy-a Randomized Trial (Gallstone PANC Trial). Ann Surg. 2019;270:519-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Riquelme F, Marinkovic B, Salazar M, Martínez W, Catan F, Uribe-Echevarría S, Puelma F, Muñoz J, Canals A, Astudillo C, Uribe M. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy reduces hospital stay in mild gallstone pancreatitis. A randomized controlled trial. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cho NY, Chervu NL, Sakowitz S, Verma A, Kronen E, Orellana M, de Virgilio C, Benharash P. Effect of surgical timing on outcomes after cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis. Surgery. 2023;174:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Papachristou GI, Muddana V, Yadav D, O'Connell M, Sanders MK, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC. Comparison of BISAP, Ranson's, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications, and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:435-41; quiz 442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vege SS, DiMagno MJ, Forsmark CE, Martel M, Barkun AN. Initial Medical Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis: American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1103-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Podda M, Pacella D, Pellino G, Coccolini F, Giordano A, Di Saverio S, Pata F, Ielpo B, Virdis F, Damaskos D, De Simone B, Agresta F, Sartelli M, Leppaniemi A, Riboni C, Agnoletti V, Mole D, Kluger Y, Catena F, Pisanu A; MANCTRA-1 Collaborative Group; Principal Investigator; Steering Committee; MANCTRA-1 Coordinating Group; Local Collaborators; Argentina; Australia; Bahrain; Brazil; Bulgaria; China; Colombia; Czech Republic; Egypt; France; Georgia; Greece; Guatemala; India; Italy; Jordan; Malaysia; Mexico; Nigeria; Pakistan; Paraguay; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Portugal; Qatar; Romania; Russia; Serbia; Slovak Republic; South Africa; Spain; Sudan; Switzerland; Syria; Tunisia; Turkey; United Kingdom; Uruguay; Yemen. coMpliAnce with evideNce-based cliniCal guidelines in the managemenT of acute biliaRy pancreAtitis): The MANCTRA-1 international audit. Pancreatology. 2022;22:902-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Di Martino M, Ielpo B, Pata F, Pellino G, Di Saverio S, Catena F, De Simone B, Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Damaskos D, Mole D, Murzi V, Leppaniemi A, Pisanu A, Podda M; MANCTRA-1 Collaborative Group. Timing of Cholecystectomy After Moderate and Severe Acute Biliary Pancreatitis. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:e233660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schepers NJ, Hallensleben NDL, Besselink MG, Anten MGF, Bollen TL, da Costa DW, van Delft F, van Dijk SM, van Dullemen HM, Dijkgraaf MGW, van Eijck CHJ, Erkelens GW, Erler NS, Fockens P, van Geenen EJM, van Grinsven J, Hollemans RA, van Hooft JE, van der Hulst RWM, Jansen JM, Kubben FJGM, Kuiken SD, Laheij RJF, Quispel R, de Ridder RJJ, Rijk MCM, Römkens TEH, Ruigrok CHM, Schoon EJ, Schwartz MP, Smeets XJNM, Spanier BWM, Tan ACITL, Thijs WJ, Timmer R, Venneman NG, Verdonk RC, Vleggaar FP, van de Vrie W, Witteman BJ, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy versus conservative treatment in predicted severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (APEC): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hallensleben ND, Stassen PMC, Schepers NJ, Besselink MG, Anten MGF, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, da Costa DW, van Dijk SM, van Dullemen HM, Dijkgraaf MGW, van Eijck B, van Eijck CHJ, Erkelens W, Erler NS, Fockens P, van Geenen EM, van Grinsven J, Hazen WL, Hollemans RA, van Hooft JE, Jansen JM, Kubben FJGM, Kuiken SD, Poen AC, Quispel R, de Ridder RJ, Römkens TEH, Schoon EJ, Schwartz MP, Seerden TCJ, Smeets XJNM, Spanier BWM, Tan ACITL, Thijs WJ, Timmer R, Umans DS, Venneman NG, Verdonk RC, Vleggaar FP, van de Vrie W, van Wanrooij RLJ, Witteman BJ, van Santvoort HC, Bouwense SAW, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Patient selection for urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography by endoscopic ultrasound in predicted severe acute biliary pancreatitis (APEC-2): a multicentre prospective study. Gut. 2023;72:1534-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee SY, Park SH, Do MY, Lee DK, Jang SI, Cho JH. Increased ERCP-related adverse event from premature urgent ERCP following symptom onset in acute biliary pancreatitis with cholangitis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:13663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, Anderloni A, Arvanitakis M, Ah-Soune P, Barthet M, Domagk D, Dumonceau JM, Gigot JF, Hritz I, Karamanolis G, Laghi A, Mariani A, Paraskeva K, Pohl J, Ponchon T, Swahn F, Ter Steege RWF, Tringali A, Vezakis A, Williams EJ, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:472-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fujita N, Yasuda I, Endo I, Isayama H, Iwashita T, Ueki T, Uemura K, Umezawa A, Katanuma A, Katayose Y, Suzuki Y, Shoda J, Tsuyuguchi T, Wakai T, Inui K, Unno M, Takeyama Y, Itoi T, Koike K, Mochida S. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis 2021. J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:801-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Petrov MS, Savides TJ. Systematic review of endoscopic ultrasonography versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for suspected choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 2009;96:967-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Staubli SM, Kettelhack C, Oertli D, von Holzen U, Zingg U, Mattiello D, Rosenberg R, Mechera R, Rosenblum I, Pfefferkorn U, Kollmar O, Nebiker CA. Efficacy of intraoperative cholangiography versus preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with intermediate risk for common bile duct stones. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:1898-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Qayed E, Shah R, Haddad YK. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Decreases All-Cause and Pancreatitis Readmissions in Patients With Acute Gallstone Pancreatitis Who Do Not Undergo Cholecystectomy: A Nationwide 5-Year Analysis. Pancreas. 2018;47:425-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | García de la Filia Molina I, García García de Paredes A, Martínez Ortega A, Marcos Carrasco N, Rodríguez De Santiago E, Sánchez Aldehuelo R, Foruny Olcina JR, González Martin JÁ, López Duran S, Vázquez Sequeiros E, Albillos A. Biliary sphincterotomy reduces the risk of acute gallstone pancreatitis recurrence in non-candidates for cholecystectomy. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1567-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Velamazán R, López-Guillén P, Martínez-Domínguez SJ, Abad Baroja D, Oyón D, Arnau A, Ruiz-Belmonte LM, Tejedor-Tejada J, Zapater R, Martín-Vicente N, Fernández-Esparcia PJ, Julián Gomara AB, Sastre Lozano V, Manzanares García JJ, Chivato Martín-Falquina I, Andrés Pascual L, Torres Monclus N, Zaragoza Velasco N, Rojo E, Lapeña-Muñoz B, Flores V, Díaz Gómez A, Cañamares-Orbís P, Vinzo Abizanda I, Marcos Carrasco N, Pardo Grau L, García-Rayado G, Millastre Bocos J, Garcia Garcia de Paredes A, Vaamonde Lorenzo M, Izagirre Arostegi A, Lozada-Hernández EE, Velarde-Ruiz Velasco JA, de-Madaria E. Symptomatic gallstone disease: Recurrence patterns and risk factors for relapse after first admission, the RELAPSTONE study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:286-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Akshintala VS, Kanthasamy K, Bhullar FA, Sperna Weiland CJ, Kamal A, Kochar B, Gurakar M, Ngamruengphong S, Kumbhari V, Brewer-Gutierrez OI, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, van Geenen EM, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:1-6.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ridtitid W, Kulpatcharapong S, Piyachaturawat P, Angsuwatcharakon P, Kongkam P, Rerknimitr R. The impact of empiric endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy on future gallstone-related complications in patients with non-severe acute biliary pancreatitis whose cholecystectomy was deferred or not performed. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3325-3333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Weissman S, Sharma S, Ehrlich D, Aziz M, Bangolo A, Gade A, Thompson-Edwards A, Singla K, Venkatesh HK, Hoo Kim M, Muthineni VAB, Makrani M, Muthukumar A, Gurumurthy V, Prasad BA, Nemalikanti S, Thomas J, Kasarapu RB, Chugh R, Narayan KL, Acharya A, Pandol SJ, Tabibian JH. The role and timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in acute biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis: A nationwide analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:767-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pécsi D, Gódi S, Hegyi P, Hanák L, Szentesi A, Altorjay I, Bakucz T, Czakó L, Kovács G, Orbán-Szilágyi Á, Pakodi F, Patai Á, Szepes Z, Gyökeres T, Fejes R, Dubravcsik Z, Vincze Á; Hungarian Endoscopy Study Group. ERCP is more challenging in cases of acute biliary pancreatitis than in acute cholangitis - Analysis of the Hungarian ERCP registry data. Pancreatology. 2021;21:59-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ramai D, Heaton J, Abomhya A, Morris J, Adler DG. Frailty Is Independently Associated with Higher Mortality and Readmissions in Patients with Acute Biliary Pancreatitis: A Nationwide Inpatient Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:2196-2203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kamarajah SK, Karri S, Bundred JR, Evans RPT, Lin A, Kew T, Ekeozor C, Powell SL, Singh P, Griffiths EA. Perioperative outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4727-4740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Niknami M, Tahmasbi H, Firouzabadi SR, Mohammadi I, Mofidi SA, Alinejadfard M, Aarabi A, Sadraei S. Frailty as a predictor of mortality and morbidity after cholecystectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Siddiqui AA, Mitroo P, Kowalski T, Loren D. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with or without cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis in high-risk surgical patients: a decision analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1059-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Iqbal U, Anwar H, Khan MA, Weissman S, Kothari ST, Kothari TH, Confer BD, Khara HS. Safety and Efficacy of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Nonagenarians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:1352-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ramai D, Heaton J, Ofosu A, Gkolfakis P, Chandan S, Tringali A, Barakat MT, Hassan C, Repici A, Facciorusso A. Influence of Frailty in Patients Undergoing Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography for Biliary Stone Disease: A Nationwide Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:3605-3613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Takada T, Isaji S, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Takeyama Y, Itoi T, Sano K, Iizawa Y, Masamune A, Hirota M, Okamoto K, Inoue D, Kitamura N, Mori Y, Mukai S, Kiriyama S, Shirai K, Tsuchiya A, Higuchi R, Hirashita T. JPN clinical practice guidelines 2021 with easy-to-understand explanations for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29:1057-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Singh AN, Kilambi R. Single-stage laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with gallbladder stones with common bile duct stones: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials with trial sequential analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3763-3776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/