Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.114079

Revised: September 23, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 105 Days and 18.3 Hours

Early postoperative anastomosis-related complications are frequently associated with technical defects during the anastomotic procedure. Few studies focused on intraoperative anastomotic complications in esophagojejunostomy with circular stapler.

To explore whether endoscopic examination could reduce the occurrence of early postoperative anastomotic complications.

Clinical data from 160 patients with gastric cancer who underwent laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy using a circular stapler at Nanchong Central Hospital from January 2020 to December 2023 were retrospectively ana

All patients successfully underwent laparoscopic total gastrectomy with esopha

Routine IEE significantly reduces early anastomotic complications by enabling immediate detection and repair of technical defects in esophagojejunostomy with circular stapler.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that routine intraoperative endoscopic examination (IEE) during circular stapler esophagojejunostomy significantly reduces early anastomotic complications by enabling immediate detection and repair of technical defects such as leaks, bleeding, strictures, and full-thickness tears. In a retrospective analysis of 160 patients undergoing laparoscopic total gastrectomy, the IEE group had no postoperative anastomotic complications compared to 7.5% in the non-IEE group, despite a modest increase in operative time. These findings support the integration of IEE as a standard practice to enhance surgical safety and outcomes in gastric cancer surgery.

- Citation: Gong L, Yu J, Lv ZB, Qin XZ, Li M, Guo W, Huang B, Tian YH. Reducing anastomotic complications with endoscopy in laparoscopic total gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 114079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/114079.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.114079

The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for early and advanced gastric cancer, particularly distal gastric cancer, have been well established[1-4]. In recent years, with an increase in cases of upper gastric cancer and esophagogastric junction cancer, the number of patients undergoing laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) has risen significantly[5]. Roux-en-Y reconstruction remains the most commonly employed technique following LTG. Esophagojejunostomy, a key component of this procedure, can be performed using various methods, including circular stapler anastomosis, linear stapler anastomosis, and suture anastomosis[6].

Intraoperative anastomosis-associated complications, including bleeding, discontinuities, strictures, and full-thickness tears, present substantial risks. If not addressed in a timely manner, these complications can lead to severe postoperative outcomes, including life-threatening conditions[7]. Intraoperative endoscopic examination (IEE) has become a valuable means for the real-time evaluation of anastomotic integrity[8]. Techniques such as the methylene blue test, air insufflation test, and the combined gastroscopic-assisted monitoring (GAM) procedure facilitate the immediate detection of defects, enabling prompt repair and potentially reducing the risk of severe postoperative complications[9,10]. However, the effectiveness of routine IEE in preventing anastomotic complications after LTG remains a subject of controversy, as different studies have reported varying outcomes[11]. Recent progress in endoscopic imaging, such as high-definition white light endoscopy, narrow-band imaging, and blue laser imaging, has further improved the detection sensitivity of mucosal abnormalities and microvascular irregularities[12]. Additionally, the incorporation of indocyanine green fluorescence angiography in some centers offers supplementary intraoperative assessment of tissue perfusion, a crucial factor in anastomotic healing[13].

This study highlights the integration of IEE with the management of complications associated with circular stapler based esophagojejunostomy. Special emphasis is placed on the real-time identification, prevention, and treatment of such complications during LTG. The objective is to explore effective strategies for reducing esophagojejunal anastomosis-related complications and to provide a practical reference for clinical practice.

The clinical data of 160 patients with gastric cancer who underwent LTG with esophagojejunostomy using circular stapler reconstruction at Nanchong Central Hospital from January 2020 to December 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Based on whether IEE was performed, patients were divided into IEE group and non-IEE (NIEE) group. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanchong Central Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Preoperative diagnosis of gastric cancer confirmed by gastroscopy and pathological examination; (2) LTG was performed; and (3) Reconstruction of esophagojejunal anastomosis using a circular stapler. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Prior systemic radiotherapy for gastric cancer; (2) Peritoneal metastasis confirmed by intraoperative exploration; (3) T4b tumors (invasion into adjacent organs such as pancreas, colon, or spleen) requiring combined organ resection; (4) Previous major upper abdominal surgery (e.g., gastrectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy); and (5) Conversion to open surgery.

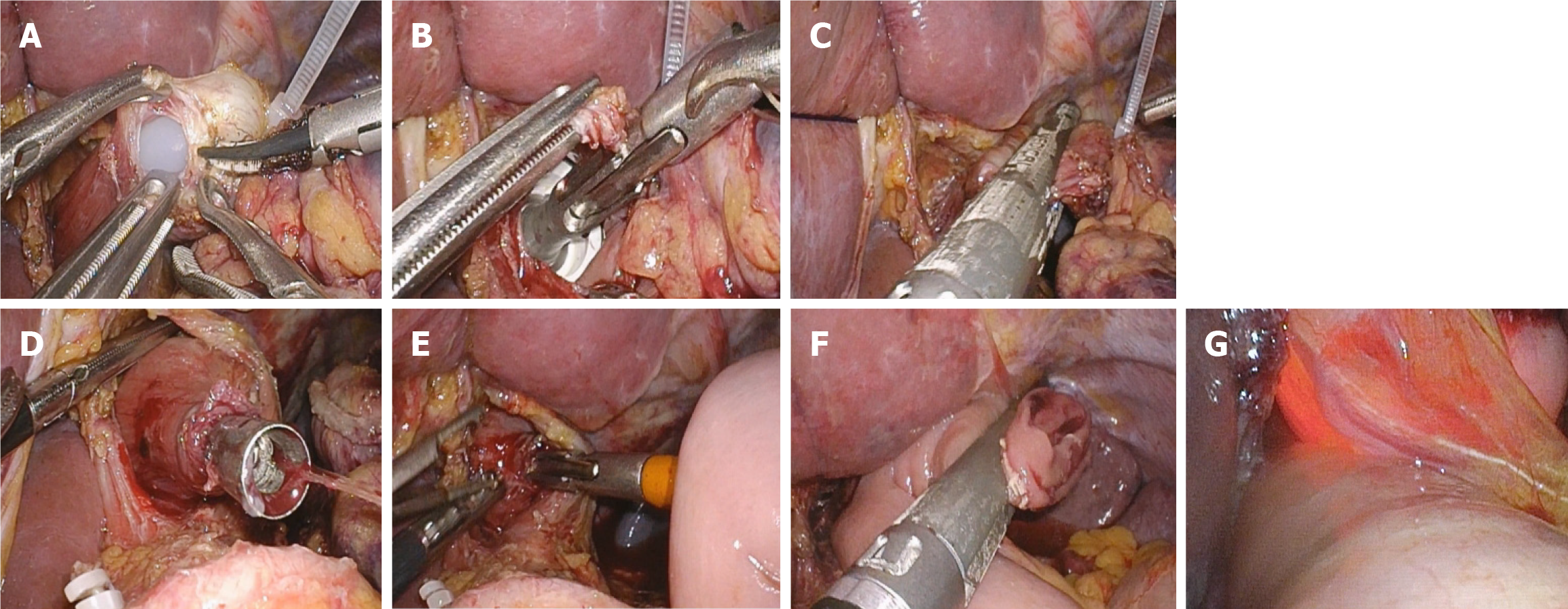

LTG was performed using five trocars. Lymph node dissection was conducted following the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines (5th edition)[14]. The duodenum was transected using a linear stapler (Echelon 60, Ethicon Endo-Surgery), and the duodenal stump was subsequently reinforced with a purse-string suture. Roux-en-Y reconstruction was employed for esophagojejunostomy. Esophagojejunostomy was performed using the hemidouble stapling technique with circular stapler (ECS 25, Ethicon Endo-Surgery)[15] (Figure 1A-F).

After completion of the anastomosis, the GAM procedure was utilized[16]. An Olympus 170 gastroscope (Olympus, Japan) was used to perform anastomotic testing. The endoscopic examination procedure was conducted as follows: (1) Anastomotic integrity was directly observed under gastroscopy; (2) The anastomosis was immersed in 500-1000 mL of warm saline solution; the distal bowel was temporarily clamped, and the jejunum was inflated with air; and (3) Gas was aspirated from the anastomosis, followed by injection of 60 mL of 1% methylene blue through the gastroscope (Figure 1G). If bubble formation or methylene blue leakage was observed at the anastomotic site, intraoperative anastomotic leakage was diagnosed and repaired by suturing.

Anastomotic leakage was defined as the leakage of contents from the lumen of the digestive tract into the extra-luminal space due to a defect in the tissue wall at the anastomotic site. The diagnosis is confirmed if blue fluid is drained after oral administration of methylene blue, or if extravasation of contrast medium is observed on upper gastrointestinal contrast radiography using diatrizoate meglumine or lipiodol. Anastomotic bleeding was defined as the presence of bloody drainage through the nasogastric tube, hematemesis, or hematochezia, which may be accompanied by alterations in vital signs (such as changes in heart rate and blood pressure) and a decrease in hemoglobin concentration. Emergency endoscopy was performed when necessary to confirm the diagnosis and treatment. Anastomotic stenosis is characterized by a narrowing of the lumen due to excessive scar tissue hyperplasia, fibrosis, or other causes, leading to obstructive symptoms. Patients often present with postoperative dysphagia. The condition was diagnosed and evaluated regarding the location and severity of the stenosis through imaging studies such as contrast radiography or gastroscopy[17]. These postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification[18]. All patients underwent a minimum postoperative follow-up of 6 months to monitor clinical outcomes.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution were presented as the mean ± SD and compared via the independent samples t-test. Continuous variables with non-normal distribution were presented as the median (interquartile range) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies (percentages) and evaluated by the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify independent risk factors associated with postoperative anastomotic complications. Variables incorporated into the model were selected based on their clinical relevance or a univariate association with a P value < 0.1. The goodness-of-fit of the logistic regression model was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, which demon

From January 2020 to December 2023, a total of 160 patients who underwent laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy using circular stapler reconstruction were retrospectively analyzed. The clinical characteristics of patients in the IEE and NIEE groups were summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | IEE (n = 77) | NIEE (n = 83) | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Sex (male/female) | 56/21 | 66/17 | 0.278 |

| Age (years) | 61.3 ± 9.21 | 63.2 ± 8.85 | 0.463 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.75 ± 3.01 | 23.35 ± 2.78 | 0.478 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD (yes/no) | 11/66 | 17/66 | 0.691 |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 15/62 | 14/69 | 0.821 |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 9/68 | 13/70 | 0.530 |

| Degree of tumor differentiation | 0.356 | ||

| High | 17 | 14 | |

| Medium | 29 | 33 | |

| Low | 31 | 36 | |

| Pathological stage | 0.782 | ||

| IA/IB | 11 | 9 | |

| II | 25 | 29 | |

| IIIA/IIIB | 41 | 45 |

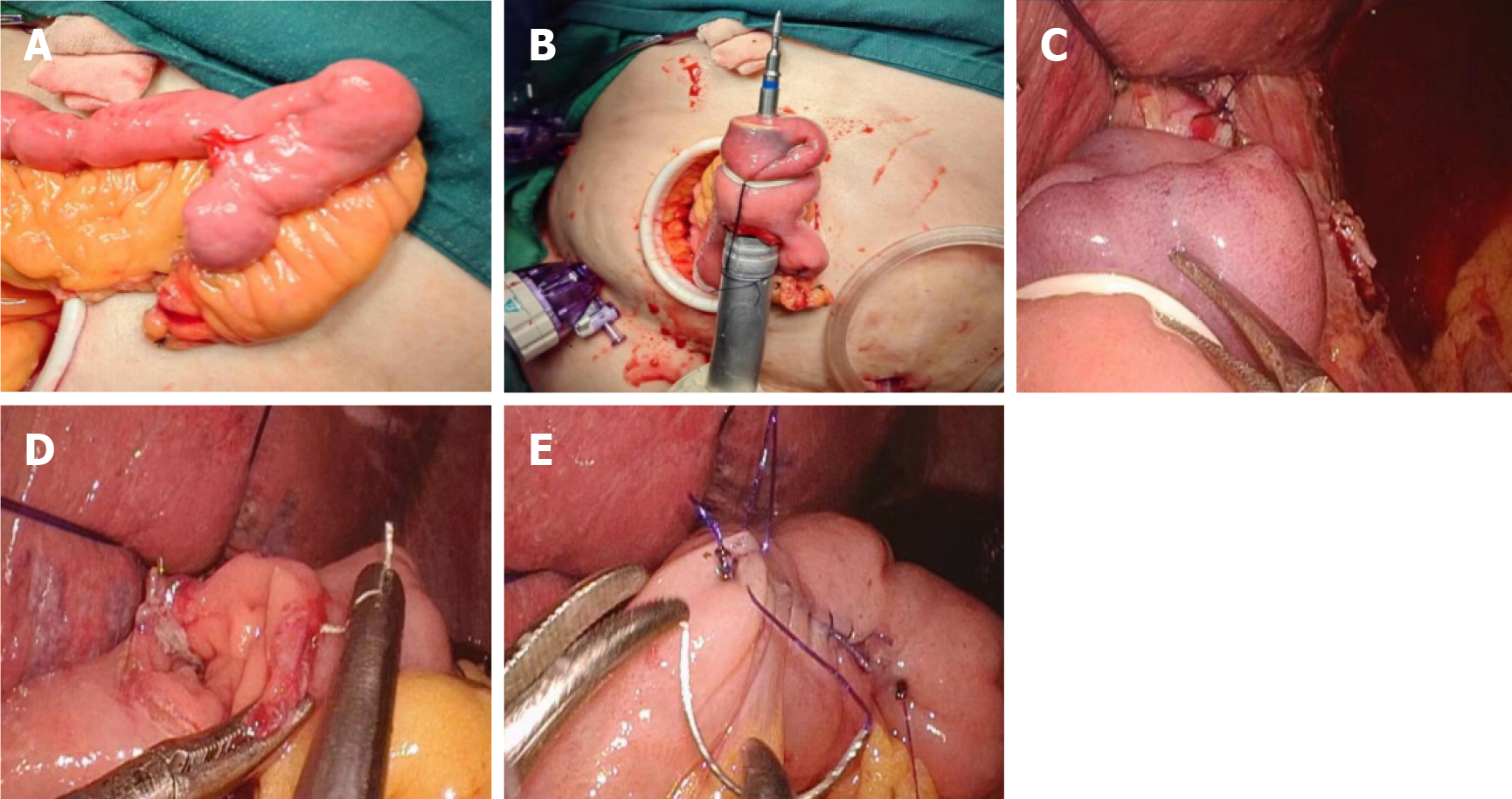

In the IEE group, 7 (8.8%) patients were found to have anastomotic defects: 3 (3.8%) air leaks, 2 (2.5%) bleeding, 1 (1.3%) stricture, and 1 (1.3%) full-thickness tearing. Table 2 details the surgical characteristics of patients with positive IEE. Three patients with anastomotic discontinuities were subsequently treated with additional suturing. One anastomotic bleeding was managed with laparoscopic suturing, and another was treated with endoscopic clips due to intrathoracic anasto

| Patient No. | Defect type | Management | Postoperative anastomotic complications | Postoperative hospital stay (days) |

| 1 | Anastomotic discontinuity | Suturing | No | 10 |

| 2 | Anastomotic discontinuity | Suturing | No | 11 |

| 3 | Anastomotic discontinuity | Suturing | No | 10 |

| 4 | Anastomotic bleeding | Endoscopic clamping | No | 9 |

| 5 | Anastomotic bleeding | Suturing | No | 12 |

| 6 | Anastomotic stricture | ESANR[16] | No | 11 |

| 7 | Full-thickness tearing | Redo anastomosis | No | 13 |

| Variables | IEE (n = 77) | NIEE (n = 83) | P value |

| Mean operation time (minutes) | 308.5 ± 81.3 | 281 ± 75.6 | 0.037 |

| Mean blood loss (mL) | 105.7 ± 52.8 | 110.4 ± 65.2 | 0.745 |

| Number of retrieved lymph nodes | 28.5 ± 12.2 | 32.7 ± 10.8 | 0.178 |

| Maximum tumor diameter (cm) | 4.35 ± 2.16 | 4.05 ± 2.56 | 0.563 |

| Proximal margin length (cm) | 3.15 ± 2.05 | 3.26 ± 2.28 | 0.925 |

| Distal margin length (cm) | 7.38 ± 3.78 | 7.53 ± 3.21 | 0.672 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 12.94 ± 2.12 | 11.73 ± 1.78 | 0.452 |

| Anastomosis-related complications | 0.029 | ||

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 | 5 | |

| Anastomotic bleeding | 0 | 0 | |

| Anastomotic stricture | 0 | 1 |

In the NIEE group, 6 cases (7.5%) of postoperative anastomotic complications were observed (Table 3). The incidence of postoperative anastomosis-related complications in the NIEE group was significantly higher than that in the IEE group (7.5% vs 0%; P = 0.029). Nevertheless, there was no significant inter-group difference in the length of hospital stay (P > 0.05). Postoperatively, anastomotic leakage occurred in 5 patients. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, 3 patients were classified as grade I, and 2 as grade II; all cases were resolved through conservative management. One patient developed anastomotic stricture one month after the operation, and complete resolution was achieved after endoscopic dilation therapy.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the independent risk factors for postoperative anastomotic complications (Table 4). The utilization of IEE was recognized as a significant protective factor (odds ratio = 0.12, 95% confidence interval: 0.04-0.41, P = 0.001). Other factors, such as tumor stage, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes, and operative duration, were not significantly correlated with anastomotic complications in the multivariate model.

| Variable | β | SE | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| IEE (yes vs no) | -2.12 | 0.62 | 0.12 (0.04-0.41) | 0.001 |

| Tumor stage (III vs I/II) | 0.61 | 0.32 | 1.84 (0.98-3.45) | 0.058 |

| COPD (yes vs no) | 0.49 | 0.41 | 1.63 (0.73-3.64) | 0.233 |

| Hypertension (yes vs no) | 0.25 | 0.38 | 1.28 (0.61-2.71) | 0.512 |

| Diabetes (yes vs no) | 0.37 | 0.39 | 1.45 (0.68-3.10) | 0.341 |

| Operative time (extend per 30 minutes) | 0.18 | 0.10 | 1.20 (0.98-1.46) | 0.072 |

In 2009, Omori et al[15] first introduced the hemidouble stapling technique, which addressed the issue of anvil placement and significantly expanded the use of circular staplers in esophagojejunostomy reconstruction. This anastomotic approach offers several advantages, including achieving a higher esophageal resection margin and eliminating the need for manual closure of a common entry hole. Low-quality anastomosis in esophagojejunostomy can lead to severe postoperative complications, including anastomotic bleeding, leakage, and stricture. These complications may result in prolonged hospital stays, increased medical costs, and even mortality[19,20]. Previous literature has reported various intraoperative methods for preventing esophagojejunostomy leakage, such as the methylene blue test or a comprehensive leak detection approach combining gastroscopy, air insufflation, and methylene blue (GAM)[16]. At our institution, some researchers advocated the use of intraoperative gastroscopic leak detection, which has been shown to effectively prevent anastomotic complications in esophagojejunostomy for gastric cancer surgery[9,10]. However, there is controversy over whether IEE can effectively prevent anastomotic leakage after total gastrectomy[21-24]. Our study revealed a significantly lower incidence of postoperative anastomotic complications in the IEE group vs the NIEE group, although the mean operative time was prolonged by 28 minutes in the IEE group.

In the IEE group, 7 (8.8%) patients were found to have anastomotic defects: 3 (3.8%) air leaks, 2 (2.5%) bleeding, 1 (1.3%) stricture and 1 (1.3%) full-thickness tearing. Kanaji et al[22] reported a 3.2% intraoperative leakage rate in patients undergoing open total gastrectomy. In comparison, Park et al[24] utilized intraoperative endoscopy for anastomotic evaluation, revealing a 9.71% positive rate in the leak detection group among gastric cancer patients. In this study, 3 patients (3.8%) were identified with anastomotic discontinuity in the IEE group. After reinforced suturing was performed intraoperatively, no anastomotic leakage occurred postoperatively.

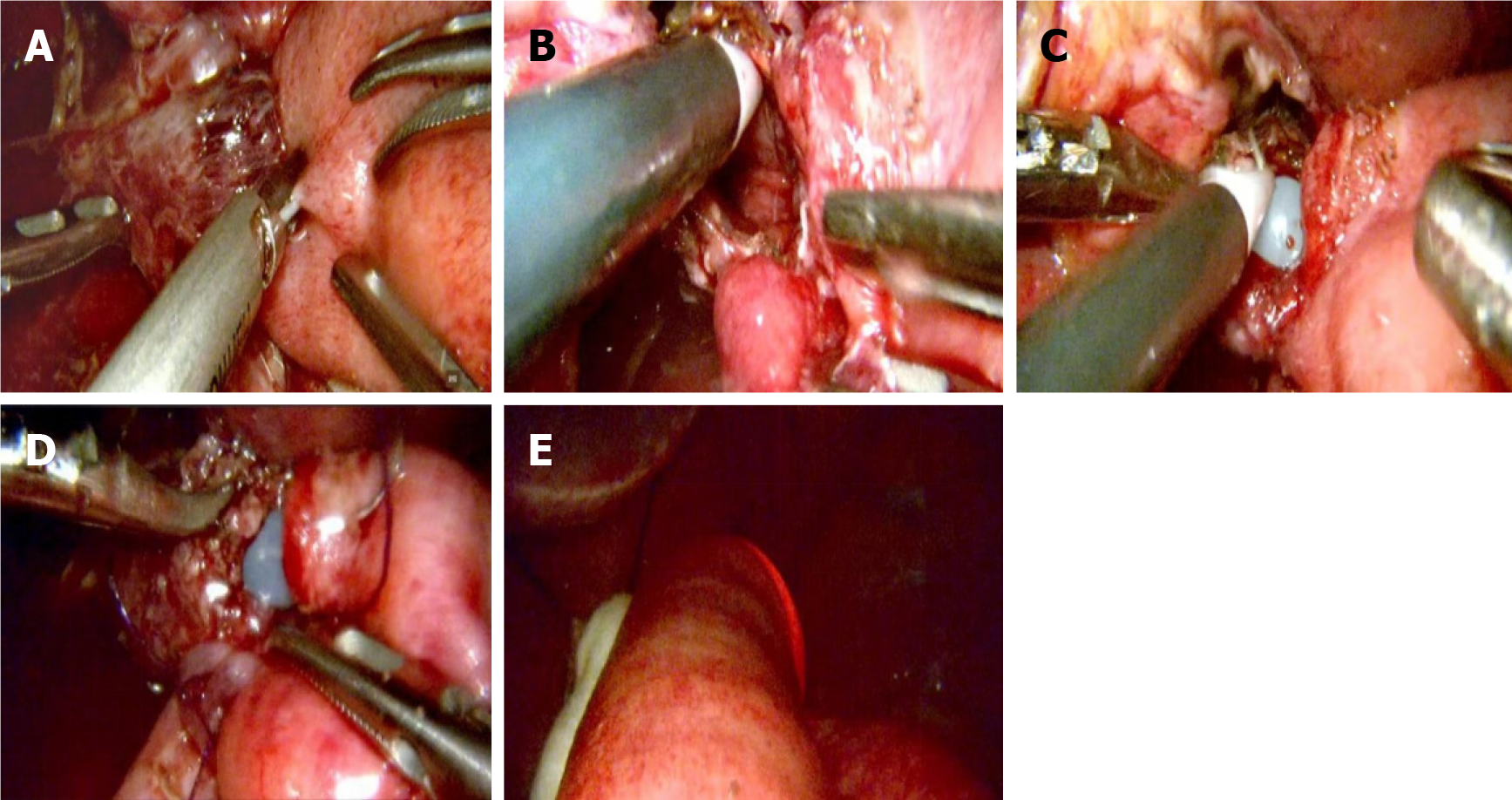

Anastomotic bleeding is an early complication after esophagojejunostomy, with an incidence of approximately 2%[25]. The causes of postoperative anastomotic bleeding were as follows: (1) Improper selection of staple height resulted in poor staple formation and inadequate compressive hemostasis; (2) The stapler was not fully fired in one attempt, leading to incomplete anastomosis and poor vascular closure; (3) Surrounding tissues were embedded in the anastomosis, resulting in insufficient closure of small vessels; (4) The tube stapler was either too loosely or too tightly rotated, causing incom

Although early stricture of the esophagojejunal anastomosis is a concern for surgeons, it has rarely been reported in the literature. Lee[26] described a case in which a pseudolumen was created during linear stapler anastomosis, resulting in early anastomotic stricture. This was successfully managed with endoscopic release of the covering mucosa postoperatively[21]. Nishikawa et al[27] reported two cases of jejunal obstructions that occurred because of a full-thickness jejunal trap in the jejunal limb caused by the circular stapler during the anastomosis. For the two cases, re-anastomosis was performed[22]. In this study, the IEE group reported one case of intraoperative anastomotic stricture, which occurred because the jejunal mucosa on the mesenteric side of the efferent limb was inadvertently incorporated into staple line. Detaching the jejunal mucosa which stapled in the anastomosis prevented re-anastomosis. After successful intraoperative correction, no postoperative stricture or anastomotic leakage occurred.

Full-thickness tearing at the esophagojejunal anastomosis is a severe intraoperative complication during circular stapler esophagojejunostomy. In cases of complete anastomotic tear, surgical takedown and re-anastomosis should be considered. However, limited guidance exists in the literature for managing such scenarios clinically. Understanding the etiology of anastomotic tears is crucial for prevention. Contributing factors include: (1) Using an oversized circular stapler in a narrow jejunal lumen can cause damage; and (2) Excessive force during insertion may injure the tissue. Re-anastomosis poses technical challenges, particularly for supra-diaphragmatic anastomoses. In IEE group, one case of full-thickness anastomotic mucosal tear was identified. Postoperative leakage or obstruction was absent following re-anastomosis.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis further verified that IEE served as an independent protective factor against anastomotic complications (odds ratio = 0.12, P = 0.001), highlighting its crucial role in alleviating technical deficiencies during esophagojejunostomy. Although tumor stage, comorbidities, and operative duration have been previously associated with anastomotic outcomes, our analysis did not identify them as significant predictors within this cohort. This implies that the immediate intraoperative detection and rectification of defects, facilitated by endoscopy, may supersede other patient - or surgery - related factors in preventing early anastomotic complications. These findings strengthen the recommendation for the routine incorporation of IEE in LTG to improve surgical safety and outcomes.

This research exhibits several limitations. Firstly, its retrospective design might give rise to selection bias, despite our efforts to alleviate this issue via time-based allocation. Secondly, the single-center characteristic of the study could restrict the generalizability of the research findings. Thirdly, although IEE notably diminished early complications, its influence on long-term outcomes, including anastomotic stricture or quality of life, remains ambiguous and necessitates further exploration. Future prospective, multi-center studies are required to validate the findings of this research.

IEE is a promising method for effectively identifying anastomotic bleeding, discontinuities, strictures, and full-thickness tears. This approach allows for immediate, individualized interventions to be performed intraoperatively, thereby preventing severe postoperative anastomotic complications.

| 1. | Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Wang K, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Du X, Hu Y, Liu H, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Liu F, Li Z, Zhao G, Yang K, Liu C, Li H, Chen P, Ji J, Li G; Chinese Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (CLASS) Group. Effect of Laparoscopic vs Open Distal Gastrectomy on 3-Year Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The CLASS-01 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1983-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hyung WJ, Yang HK, Park YK, Lee HJ, An JY, Kim W, Kim HI, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Hur H, Kim MC, Kong SH, Cho GS, Kim JJ, Park DJ, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Kim JW, Lee JH, Han SU; Korean Laparoendoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study Group. Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The KLASS-02-RCT Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3304-3313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kim W, Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Kim CY, Yang HK, Park DJ, Song KY, Lee SI, Ryu SY, Lee JH, Lee HJ; Korean Laparo-endoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study (KLASS) Group. Decreased Morbidity of Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy Compared With Open Distal Gastrectomy for Stage I Gastric Cancer: Short-term Outcomes From a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (KLASS-01). Ann Surg. 2016;263:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Morita S, Yamada T, Bando E, Ito S, Takagi M, Takagane A, Teshima S, Koeda K, Nunobe S, Yoshikawa T, Terashima M, Sasako M. Survival outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA or IB gastric cancer (JCOG0912): a multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:142-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shen J, Ma X, Yang J, Zhang JP. Digestive tract reconstruction options after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:21-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gastric Cancer Professional Committee; Chinese Anti-Cancer Association (CACA); Gastrointestinal Surgery Group, Branch of Surgery, Chinese Medical Association; Committee of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons, Branch of Surgery, Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Digestive Tumor Committee, Chinese Research Hospital Association. [Chinese expert consensus on prevention and treatment of complications related to digestive tract reconstruction after laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer (2022 edition)]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2022;25:659-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zaman S, Hussain MI, Kausar M, Mostafa OES, Mohamedahmed AY, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Camprodon R, Sellahewa C. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic total gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:3441-3455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kitagawa Y, Matsuda S, Gotoda T, Kato K, Wijnhoven B, Lordick F, Bhandari P, Kawakubo H, Kodera Y, Terashima M, Muro K, Takeuchi H, Mansfield PF, Kurokawa Y, So J, Mönig SP, Shitara K, Rha SY, Janjigian Y, Takahari D, Chau I, Sharma P, Ji J, de Manzoni G, Nilsson M, Kassab P, Hofstetter WL, Smyth EC, Lorenzen S, Doki Y, Law S, Oh DY, Ho KY, Koike T, Shen L, van Hillegersberg R, Kawakami H, Xu RH, Wainberg Z, Yahagi N, Lee YY, Singh R, Ryu MH, Ishihara R, Xiao Z, Kusano C, Grabsch HI, Hara H, Mukaisho KI, Makino T, Kanda M, Booka E, Suzuki S, Hatta W, Kato M, Maekawa A, Kawazoe A, Yamamoto S, Nakayama I, Narita Y, Yang HK, Yoshida M, Sano T. Clinical practice guidelines for esophagogastric junction cancer: Upper GI Oncology Summit 2023. Gastric Cancer. 2024;27:401-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gao Z, Chen X, Bai D, Fahmy L, Qin X, Peng Y, Ren M, Tian Y, Hu J. A Novel Intraoperative Leak Test Procedure (GAM Procedure) to Prevent Postoperative Anastomotic Leakage in Gastric Cancer Patients Who Underwent Gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2023;33:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gao Z, Luo H, Ma L, Bai D, Qin X, Bautista M, Gong L, Peng Y, Hu J, Tian Y. Efficacy and safety of anastomotic leak testing in gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:5265-5273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luo H, Liu S, Huang W, Lei Y, Xing Y, Wesemann L, Luo B, Li W, Hu J, Tian Y. A comparison of the postoperative outcomes between intraoperative leak testing and no intraoperative leak testing for gastric cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:1709-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pisani A, Libânio D, Kunovský L. Shedding a new light on gastric cancer screening. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:662-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang P, Tian Y, Du Y, Zhong Y. Intraoperative assessment of anastomotic blood supply using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging following esophagojejunostomy or esophagogastrostomy for gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1341900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 1417] [Article Influence: 283.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Omori T, Oyama T, Mizutani S, Tori M, Nakajima K, Akamatsu H, Nakahara M, Nishida T. A simple and safe technique for esophagojejunostomy using the hemidouble stapling technique in laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 2009;197:e13-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Inokuchi M, Otsuki S, Fujimori Y, Sato Y, Nakagawa M, Kojima K. Systematic review of anastomotic complications of esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9656-9665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9241] [Article Influence: 543.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Zhou J, Wang Z, Chen G, Li Y, Cai M, Pannikkodan FS, Qin X, Bai D, Lv Z, Gong L, Tian Y. A novel intraoperative Esophagus-Sparing Anastomotic Narrowing Revision (ESANR) technique for patients who underwent esophagojejunostomy: three case reports and a review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park KB, Kim EY, Song KY. Esophagojejunal Anastomosis after Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: Circular versus Linear Stapling. J Gastric Cancer. 2019;19:344-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huang H, Guo Z, Li W, Zhang M, Li Y. A comparative study of using linear anastomosis with circular anastomosis in digestive tract reconstruction after laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alemdar A, Eğin S, Yılmaz I, Kamalı S, Duman MG. Can intraoperative endoscopy prevent esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage after total gastrectomy? Hippokratia. 2021;25:108-112. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kanaji S, Ohyama M, Yasuda T, Sendo H, Suzuki S, Kawasaki K, Tanaka K, Fujino Y, Tominaga M, Kakeji Y. Can the intraoperative leak test prevent postoperative leakage of esophagojejunal anastomosis after total gastrectomy? Surg Today. 2016;46:815-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Celik S, Almalı N, Aras A, Yılmaz Ö, Kızıltan R. Intraoperatively Testing the Anastomotic Integrity of Esophagojejunostomy Using Methylene Blue. Scand J Surg. 2017;106:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Park JH, Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Kim TH, Kim JM, Kim DH, Kwag SJ, Kim JY, Park T, Jeong CY, Ju YT, Jung EJ, Hong SC. Safety and efficacy of post-anastomotic intraoperative endoscopy to avoid early anastomotic complications during gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:5312-5319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, Xue Y, Suo J, Tao K, He X, Wei H, Ying M, Hu W, Du X, Chen P, Liu H, Zheng C, Liu F, Yu J, Li Z, Zhao G, Chen X, Wang K, Li P, Xing J, Li G. Morbidity and Mortality of Laparoscopic Versus Open D2 Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1350-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 549] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee SS. Endoscopic management of pseudo-lumen stapling following laparoscopic esophagojejunostomy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;111:108830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nishikawa K, Yanaga K, Kashiwagi H, Hanyuu N, Iwabuchi S. Significance of intraoperative endoscopy in total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2633-2636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/