Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.113940

Revised: September 24, 2025

Accepted: October 28, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 109 Days and 4.6 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in segments VII and VIII poses technical challenges for both liver resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Robotic-assisted techniques may enhance safety and precision, but comparative evidence remains limited.

To compare the clinical outcomes of robotic liver resection (R-LR) and robotic intraoperative RFA (RIO-RFA) for HCC located in liver segments VII and VIII.

We retrospectively analyzed 93 HCC patients in segments VII/VIII with de novo (n = 57) or first recurrent (n = 36). HCC who underwent R-LR or RIO-RFA between 2015 and 2024. Propensity score matching was performed to reduce selection bias. Primary outcomes were overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS). Kaplan-Meier curves, log-rank tests, and Cox regression were used to identify prognostic factors for OS and RFS.

In the de novo group, OS and RFS did not differ significantly between R-LR and RIO-RFA before or after propensity score matching. In contrast, the recurrent group showed significantly improved OS and RFS with R-LR (P = 0.005 and P = 0.012, respectively). Subgroup analyses revealed that low-risk de novo patients with smaller tumors achieved superior OS after R-LR, whereas carefully selected low-risk recurrent patients undergoing RIO-RFA (smaller tumors, absence of complications) achieved outcomes comparable to R-LR. Platelet count, tumor size, and postoperative complications constituted key prognostic factors.

For HCC in challenging liver segments VII and VIII, R-LR and RIO-RFA achieve comparable outcomes in de novo cases, whereas R-LR confers superior survival in recurrent disease. R-LR should be prioritized for small de novo HCCs and for recurrent disease overall; RIO-RFA may serve as an effective alternative in carefully selected low-risk recurrent patients. Tumor size, platelet count, and postoperative complications are key prognostic indicators to guide individualized treatment.

Core Tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) located in liver segments VII and VIII presents unique surgical challenges due to their posterior-superior position. This study compared robotic liver resection (R-LR) with robotic intraoperative radiofrequency ablation (RIO-RFA) in groups with de novo and first recurrent HCC. In de novo HCC, survival outcomes were comparable between R-LR and RIO-RFA, whereas R-LR conferred superior overall and recurrence-free survival in recurrent cases. Subgroup analyses identified tumor size, platelet count, and postoperative complications as critical prognostic factors. These findings suggest R-LR should be prioritized, while RIO-RFA may remain an option in carefully selected low-risk patients.

- Citation: Peng CM, Lin SC, Cheng YY, Cheng TC, Hsieh CL, Hsieh CH, Hsieh MF, Liao CH, Liu MC, Liu YJ. Outcomes of robotic liver resection and intraoperative radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma in posterior segments VII and VIII. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 113940

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/113940.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.113940

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s Global Cancer Observatory, liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer was the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in 2022, with 758725 deaths reported. In the same year, approximately 866136 new cases of liver cancer were recorded[1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is composed of malignant epithelial cells, distinguishing it from other types of liver cancer, such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer within the liver) or metastatic cancers that spread to the liver from other parts of the body. HCC is the most common primary malignancy originating in the liver, constituting 75%-85% of all liver tumors[2].

Hepatectomy is considered a primary treatment option for HCC, particularly in patients with early-stage disease, preserved liver function, and no evidence of extrahepatic spread[3]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), which delivers high-frequency alternating current through the distal end of an uninsulated needle tip to induce coagulative necrosis and protein denaturation, serves as an alternative to surgical resection[4]. However, resections involving the posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe - particularly segments VII and VIII - are among the most technically challenging procedures[5,6]. Similarly, percutaneous RFA of tumors in the hepatic dome is technically demanding, as such tumors may be only partially visualized and carry a risk of collateral thermal injury to adjacent structures[7,8].

In such cases, robotic-assisted approaches are often preferred, as they provide enhanced precision and superior instrument control, thereby facilitating safer and more effective resections. Moreover, intraoperative RFA can serve as a valuable adjunct for managing small, surgically unfavorable, or unresectable HCCs, especially those located deep within the parenchyma or restricted to the liver remnant[9]. Previous studies have reported that hepatectomy combined with intraoperative RFA allows for removal of larger lesions while simultaneously ablating smaller residual tumors (≤ 3 cm), thereby achieving complete eradication of all detectable disease, with outcomes comparable to hepatectomy alone[10,11].

Many studies have evaluated the efficacy of various treatment modalities for HCC, including liver resection, percutaneous RFA, intraoperative RFA, and hepatectomy combined with intraoperative RFA[10-14]. However, most of these studies have focused primarily on tumor characteristics and overall treatment efficacy, rather than providing direct comparative data on treatment outcomes in specific liver segments. In particular, few studies have investigated the efficacy of hepatic resection and RFA in the posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe (segments VII and VIII), which are regarded as technically challenging regions. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of robotic liver resection (R-LR) and robotic intraoperative RFA (RIO-RFA) specifically in segments VII and VIII.

This study was designed as a retrospective review, approved as a completely ethical review by the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (Approval No. CS1-25119). Approval from the institutional research ethics board was obtained, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

We retrospectively analyzed patients with liver tumor who underwent R-LR or RIO-RFA at our institution between July 2015 and August 2024. The inclusion criteria for this study included patient with the following characteristics: (1) Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0-B with Child-Pugh class A or B; (2) R-LR or RIO-RFA performed in liver segments VII or VIII; (3) Confirmed diagnosis of HCC; (4) Patients undergoing a de novo or first recurrence HCC under R-LR or RIO-RFA procedure; and (5) R-LR or RIO-RFA performed using the da Vinci surgical robot. The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Non-robotic liver surgery; (2) Diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic liver tumors; (3) Missing key clinical data (e.g., T stage); and (4) More than two R-LR or RIO-RFA procedures.

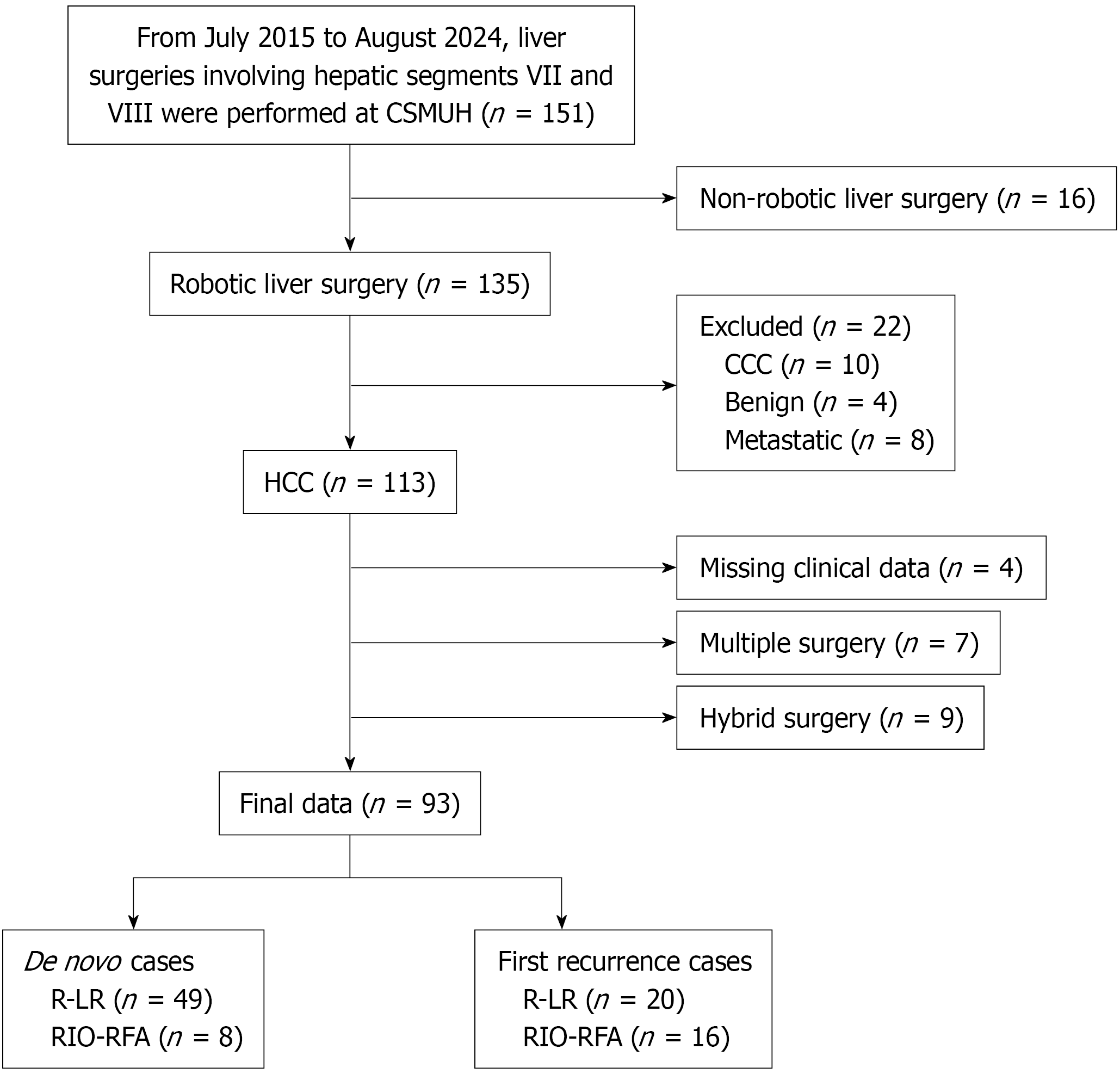

HCC diagnoses were confirmed by histopathology (resection or biopsy specimens) or by non-invasive criteria based on the European Association for the Study of the Liver/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines, using multiphase contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) combined with serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing. Ultimately, 93 patients met the eligibility criteria from an initial group of 488 HCC cases, including 57 with newly diagnosed HCC (de novo HCC) and 36 with first recurrence HCC (Figure 1).

The potential for R-LR and RIO-RFA was evaluated by CT and MRI. Liver function was evaluated based on the Child-Pugh score and standard biochemical tests. To characterize the final study group, demographic, clinical, and imaging data were retrospectively collected from the institutional database. Clinical and histopathological information included patient age, sex, tumor stage, major tumor size, aggregate tumor size, operation details, and follow-up outcomes. Additionally, data regarding prior treatments for HCC and laboratory parameters were extracted from medical records. These parameters included weight, height, body mass index, hepatitis virus status, total bilirubin, serum albumin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, platelet count, prothrombin time, AFP, and indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes.

Tumor number and location were determined using preoperative CT or MRI. Tumor size was measured by imaging (CT or MRI), intraoperative probing, or postoperative dissection. Surgical data included operation time, Surgical Apgar Score, blood loss, blood transfusion, postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay.

The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and RFS. OS was defined as the interval from surgery to death from any cause or last follow-up. RFS was defined as the interval from surgery to documented HCC recurrence.

All procedures were performed by surgeons with extensive experience in robotic liver surgery procedures using the da Vinci Xi platform (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States). R-LR was performed for patients with large tumors, difficult-to-ablate lesions, or tumors deemed resectable with preservation of adequate remnant liver function and volume, based on preoperative and intraoperative assessment. RIO-RFA was employed in cases where tumor exposure or resection was technically challenging - particularly for deep-seated tumors - or when sufficient postoperative liver function and residual volume could not be achieved with R-LR alone.

R-LR: A wedge resection was performed in R-LR patients to preserve as much functional liver tissue as possible. Patients were positioned in the reverse Trendelenburg position. Minimally invasive surgery was initiated by establishing a pneumoperitoneum (12 mmHg) and placing five trocars according to the tumor location. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging was used to identify hepatic tumors, while intraoperative ultrasonography was routinely performed to confirm resectability and define the transection plane. The procedure included dissection of the right posterior liver region, precise localization and marking of the tumor, and division of intrahepatic vessels using linear staplers, Hem-o-Lok clips, or titanium clips. Liver parenchymal transection was carried out with advanced instruments, including the scissor hepatectomy technique, vessel sealer, ultrasonic scalpel on the da Vinci Xi platform. Tumor excision was completed with meticulous hemostasis using bipolar or electrocautery devices. The resected specimen was secured in an endobag and extracted through one of the trocar sites.

RIO-RFA: For the RIO-RFA group, patients with tumors deemed unresectable preoperatively or confirmed as unresectable during intraoperative assessment underwent RIO-RFA following a standardized protocol. The preparatory steps for the da Vinci system were identical to those for R-LR, including patient positioning, trocar placement, and establishment of pneumoperitoneum. Subphrenic tumors broadly attached to the anterior capsule were directly visualized with the da Vinci system, aided by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging, whereas intraoperative ultrasonography was used to assess tumor depth and guide treatment of deep-seated or difficult-to-access lesions. Radiofrequency electrodes (HFM 01-AC0003/4; COMPAL Electronics, Inc., Taiwan) were accurately inserted under combined visual and ultrasound guidance. The generator (AblatePal; HFM01-MD2202; COMPAL Electronics, Inc., Taiwan) output was gradually increased from 80 W to 100 W with synchronous impedance monitoring and real-time ultrasound confirmation. Each ablation session lasted approximately 12 minutes and included the tumor plus a 0.5-1.0 cm margin of normal liver tissue. Overlapping ablations were applied as needed based on tumor size and number. The tract was ablated during electrode removal.

Follow-up: Postoperative follow-up included AFP, hepatitis B virus DNA, and sonography at 2-4 weeks after surgery. CT scans were performed every 3 months. From the second year onward, follow-up was scheduled every 6 months and adjusted based on individual patient needs. Recurrences were managed with re-resection, repeat RFA, or systemic therapy.

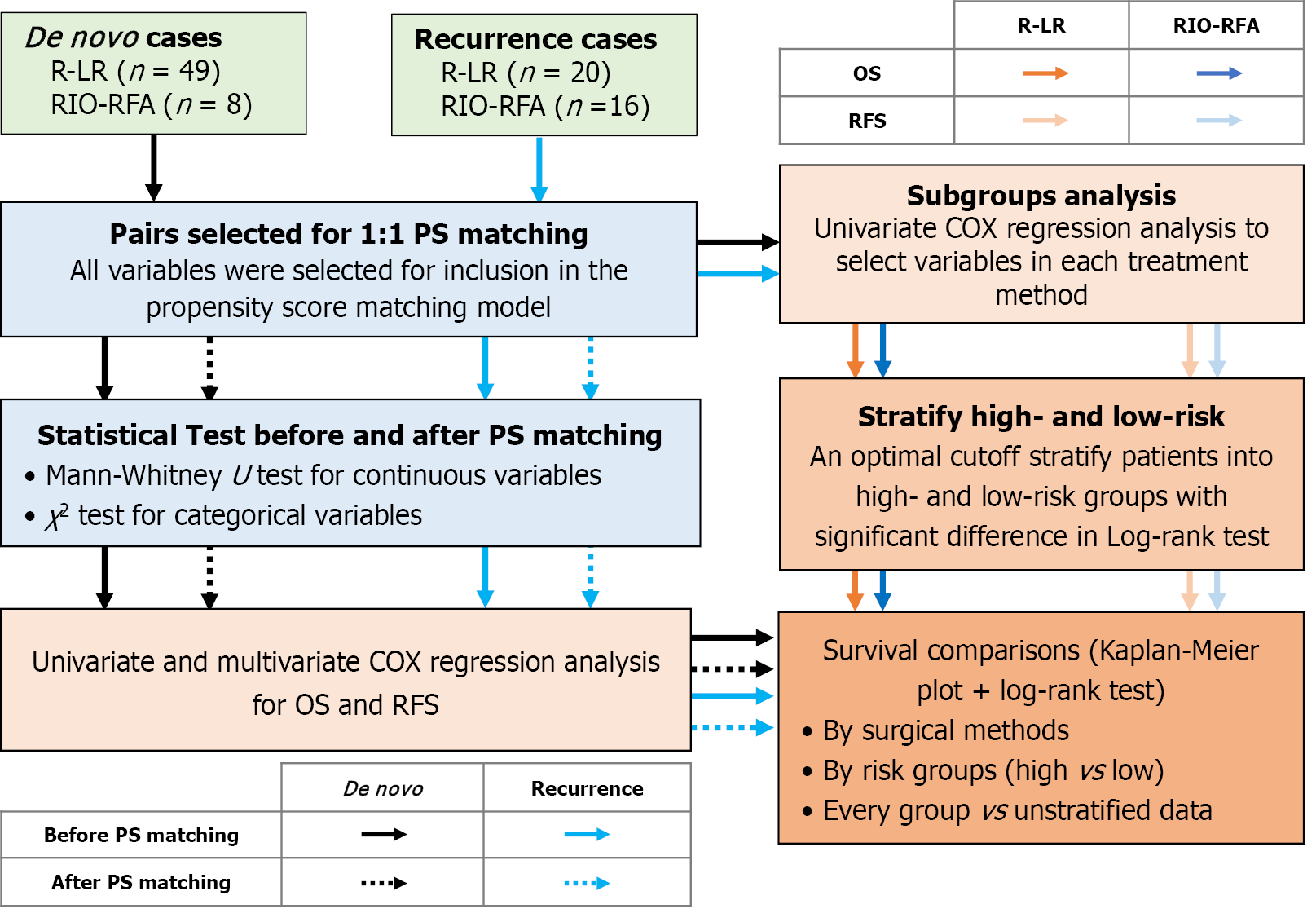

The Figure 2 illustrates the workflow for comparing OS and RFS between R-LR and RIO-RFA in HCC patients. All statistical analyses were performed using Python (version 3.10). Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD when normally distributed data, or as median with interquartile range (IQR, 25th-75th percentile) when non-normally distributed data. Group comparisons were made using the independent-samples Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. In addition, to minimize selection bias, 1:1 propensity score (PS) matching was conducted between patients undergoing R-LR and RIO-RFA. Restricted mean survival time (RMST) was also calculated to characterize OS and RFS.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify factors influencing OS and RFS for all patients. Variables with P < 0.2 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate Cox regression. Survival differences between R-LR and RIO-RFA groups were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared via the log-rank test, with P values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Subsequently, subgroup analyses were performed using Cox regression model to stratify patients within each group (R-LR and RIO-RFA) into high- and low-risk groups. The cut-off points by their median values, which served as the optimal thresholds for risk stratification (Figure 2). Survival outcomes were then compared between risk groups using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank testing. Finally, high- and low-risk groups from each group were further compared with the other group to determine which treatment provided superior outcomes within each risk category, with P values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Figure 2).

The Tables 1 and 2 summarize the baseline characteristics of patients with HCC who underwent R-LR and RIO-RFA groups in de novo HCC and first recurrence HCC groups, respectively. A total of 93 patients were enrolled, including 57 with de novo HCC and 36 with first recurrent HCC. Among the de novo cases, 49 underwent R-LR (31 males and 18 females) and eight underwent RIO-RFA (five males and three females). Among the first recurrent cases, 20 underwent R-LR (16 males and four females) and 16 underwent RIO-RFA (14 males and two females). Because the RIO-RFA group included relatively few cases, PS matching was performed by pairing patients in the R-LR group with those in the RIO-RFA group who had comparable scores.

| Variable | Before PS matching | After PS matching | ||||

| RIO-RFA (n = 8) | R-LR (n = 49) | P value | RIO-RFA (n = 8) | R-LR (n = 8) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 71.5 (68.5-74.2) | 68.0 (62.0-77.0) | 0.621 | 71.5 (68.5-74.2) | 68.0 (58.8-77.5) | 0.713 |

| Male | 5 (62.5) | 31 (63.3) | 1 | 5 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) | 1 |

| Height (cm) | 164.5 (159.8-170.2) | 162.0 (157.0-168.0) | 0.4009 | 164.5 (159.8-170.2) | 162.0 (156.5-166.5) | 0.4613 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.5 (64.8-71.0) | 66.0 (53.0-75.0) | 0.5424 | 66.5 (64.8-71.0) | 60.0 (52.8-69.8) | 0.3998 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.5 (23.0-25.4) | 23.4 (20.8-26.9) | 0.6116 | 24.5 (23.0-25.4) | 23.0 (21.1-24.8) | 0.3823 |

| HBV | 5 (62.5) | 33 (67.3) | 1 | 5 (62.5) | 6 (75.0) | 1 |

| HCV | 3 (37.5) | 13 (26.5) | 0.6735 | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 |

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 1 (12.5) | 16 (32.7) | 0.4133 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 |

| Platelet (103/mL) | 127.5 (97.2-156.5) | 169.0 (135.0-215.0) | 0.0179 | 127.5 (97.2-156.5) | 135.5 (110.0-160.0) | 0.713 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 10.8 (10.7-11.1) | 10.6 (10.3-11.1) | 0.295 | 10.8 (10.7-11.1) | 10.8 (10.4-11.0) | 0.5621 |

| AST (U/L) | 106.5 (79.0-460.8) | 244.0 (82.0-511.0) | 0.5972 | 106.5 (79.0-460.8) | 329.0 (174.0-857.5) | 0.1304 |

| ALT (U/L) | 112.0 (75.2-444.5) | 307.0 (120.0-532.0) | 0.2802 | 112.0 (75.2-444.5) | 366.5 (209.0-1018.8) | 0.1605 |

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 2 (25.0) | 8 (16.3) | 0.6194 | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 |

| Bilirubin total (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 0.2478 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 (4.0-4.6) | 4.4 (4.1-4.7) | 0.5567 | 4.2 (4.0-4.6) | 4.6 (4.4-4.7) | 0.2448 |

| ALBI (grade 1/2) | 6 (75.0)/2 (25.0) | 42 (85.7)/7 (14.3) | 0.599 | 6 (75.0)/2 (25.0) | 7 (87.5)/1 (12.5) | 1 |

| Child-Pugh (class A/B) | 7 (87.5)/1 (12.5) | 48 (98.0)/1 (2.0) | 0.2632 | 7 (87.5)/1 (12.5) | 8 (100.0)/0 (0.0) | 1 |

| T stage (1/2/3/4) | 6 (75.0)/1 (12.5)/0 (0.0)/1 (12.5) | 36 (73.5)/12 (24.5)/1 (2.0)/0 (0.0) | 0.0812 | 6 (75.0)/1 (12.5)/1(12.5) | 5 (62.5)/3 (37.5)/0 (0.0) | 0.3515 |

| Major tumor size (cm) | 1.6 (1.5-2.3) | 3.0 (1.8-4.5) | 0.0343 | 1.6 (1.5-2.3) | 2.1 (1.6-3.0) | 0.4589 |

| Aggregate tumor size (cm) | 1.6 (1.6-2.8) | 3.1 (2.1-4.5) | 0.071 | 1.6 (1.6-2.8) | 2.5 (1.9-3.0) | 0.5249 |

| Tumor numbers (1/2/3/4) | 5 (62.5)/1 (12.5)/1 (12.5)/1 (12.5) | 39 (79.6)/10 (30.4)/0 (0)/0 (0) | 0.0053 | 5 (62.5)/1 (12.5)/1(12.5)/1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5)/1 (12.5)/0 (0)/0 (0) | 0.5062 |

| Multi-tumors | 3 (37.5) | 10 (20.4) | 0.3653 | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0.5692 |

| BCLC (stage 0/A/B) | 3 (37.5)/4 (50.0)/1 (12.5) | 9 (18.4)/31 (63.3)/9 (18.4) | 0.4658 | 3 (37.5)/4 (50.0)/1(12.5) | 2 (25.0)/6 (75.0)/0 (0.0) | 0.4493 |

| Operation time (minutes) | 104.0 (68.8-128.8) | 175.0 (155.0-249.0) | 0.0002 | 104.0 (68.8-128.8) | 114.5 (93.0-182.8) | 0.2698 |

| SAS (score 2/3) | 5 (62.5)/3 (37.5) | 26 (53.1)/23 (46.9) | 0.7153 | 5 (62.5)/3 (37.5) | 4 (50.0)/4 (50.0) | 1 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 10.0 (10.0-10.0) | 350.0 (105.0-805.0) | 0.0003 | 10.0 (10.0-10.0) | 80.0 (10.0-117.5) | 0.1179 |

| Blood transfusion | 2 (25.0) | 31 (63.3)/18 (36.7) | 0.6993 | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 1 |

| Complication | 1 (12.5) | 11 (22.4) | 1 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | 1 |

| Hospital stays (days) | 9.5 (9.0-10.0) | 11.0 (9.0-14.0) | 0.3604 | 9.5 (9.0-10.0) | 10.5 (10.0-13.5) | 0.1151 |

| Variable | Before PS matching | After PS matching | ||||

| RIO-RFA (n = 8) | R-LR (n = 49) | P value | RIO-RFA (n = 8) | R-LR (n = 8) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 71.5 (62.8-75.0) | 68.0 (63.0-75.5) | 0.8608 | 71.5 (62.8-75.0) | 67.0 (63.0-74.0) | 0.7769 |

| Male | 14 (87.5) | 16 (80.0) | 0.6722 | 14 (87.5) | 13 (81.2) | 1 |

| Height (cm) | 164.0 (157.2-170.5) | 166.5 (158.8-169.2) | 0.8984 | 164.0 (157.2-170.5) | 167.5 (163.2-169.2) | 0.7196 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.5 (54.5-78.5) | 65.5 (61.5-75.0) | 0.7258 | 64.5 (54.5-78.5) | 71.2 (63.8-75.2) | 0.4063 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 (20.7-27.0) | 26.2 (23.1-26.9) | 0.6906 | 25.9 (20.7-27.0) | 26.3 (24.5-27.0) | 0.534 |

| HBV | 8 (50.0) | 14 (70.0) | 0.3793 | 8 (50.0) | 10 (62.5) | 0.7216 |

| HCV | 4 (25.0) | 6 (30.0) | 1 | 4 (25.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.7043 |

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 5 (31.2) | 7 (35.0) | 1 | 5 (31.2) | 3 (18.8) | 0.6851 |

| Platelet (103/mL) | 116.5 (89.5-151.5) | 123.0 (103.8-156.5) | 0.4737 | 116.5 (89.5-151.5) | 117.5 (98.0-145.0) | 0.91 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 10.9 (10.5-11.0) | 10.5 (10.3-10.9) | 0.0867 | 10.9 (10.5-11.0) | 10.6 (10.4-10.9) | 0.2882 |

| AST (U/L) | 323.0 (155.2-1067.2) | 194.0 (126.0-323.0) | 0.1345 | 323.0 (155.2-1067.2) | 204.0 (126.8-323.0) | 0.2 |

| ALT (U/L) | 266.5 (174.0-762.0) | 274.5 (130.0-437.5) | 0.4544 | 266.5 (174.0-762.0) | 225.5 (130.0-384.2) | 0.3558 |

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 4 (25.0) | 5 (25.0) | 1 | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 1 |

| Bilirubin total (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.3973 | 1.0 (0.6-1.4) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.5962 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 (4.0-4.6) | 4.3 (4.0-4.7) | 0.7736 | 4.5 (4.0-4.6) | 4.5 (4.1-4.7) | 0.4602 |

| ALBI (grade 1/2) | 12 (75.0)/4 (25.0) | 16 (80.0)/4 (20.0) | 1 | 12 (75.0)/4 (25.0) | 13 (81.2)/3 (18.8) | 1 |

| Child-Pugh (class A/B) | 12 (75.0)/4 (25.0) | 18 (90.0)/2 (10.0) | 0.3738 | 12 (75.0)/4 (25.0) | 14 (87.5)/2 (12.5) | 0.6539 |

| T stage (1/2/3/4) | 5 (31.2)/10 (62.5)/1 (6.2) | 13 (65.0)/6 (30.0)/1 (5.0) | 0.1248 | 5 (31.2)/10 (62.5)/1 (6.2) | 11 (68.8)/4 (25.0)/1 (6.2) | 0.0898 |

| Major tumor size (cm) | 2.3 (1.7-2.7) | 1.9 (1.5-2.8) | 0.5133 | 2.3 (1.7-2.7) | 1.9 (1.3-2.2) | 0.2993 |

| Aggregate tumor size (cm) | 3.3 (2.4-5.3) | 2.0 (1.8-3.4) | 0.0581 | 3.3 (2.4-5.3) | 1.9 (1.6-2.7) | 0.0184 |

| Tumor numbers (1/2/3/4/5) | 7 (43.8)/4 (25.0)/3 (18.8)/1 (6.2)/1 (6.2) | 13 (65.0)/5 (25.0)/2 (10.0)/0 (0)/0 (0) | 0.4463 | 7 (43.8)/4 (25.0)/3 (18.8)/1 (6.2)/1 (6.2) | 11 (68.8)/3 (18.8)/2 (12.5)/0 (0)/0 (0) | 0.5198 |

| Multi-tumors | 9 (56.2) | 7 (35.0) | 0.3485 | 9 (56.2) | 5 (31.2) | 0.285 |

| BCLC (stage 0/A/B) | 1 (6.2)/12 (75.0)/3 (18.8) | 6 (30.0)/12 (60.0)/2 (10.0) | 0.1856 | 1 (6.2)/12 (75.0)/3 (18.8) | 6 (37.5)/9 (56.2)/1 (6.2) | 0.0821 |

| Operation time (minutes) | 109.5 (100.0-175.5) | 167.5 (128.5-197.2) | 0.1043 | 109.5 (100.0-175.5) | 164.5 (128.5-176.0) | 0.1998 |

| SAS (score 2/3) | 9 (56.2)/7 (43.8) | 12 (60.0)/8 (40.0) | 1 | 9 (56.2)/7 (43.8) | 11 (68.8)/5 (31.2) | 0.715 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 10.0 (10.0-55.0) | 175.0 (77.5-326.2) | 0.0046 | 10.0 (10.0-55.0) | 175.0 (10.0-266.2) | 0.0174 |

| Blood transfusion | 5 (31.2) | 7 (35.0) | 1 | 5 (31.2) | 5 (31.2) | 1 |

| Complication | 5 (31.2) | 2 (10.0) | 0.2036 | 5 (31.2) | 2 (12.5) | 0.3944 |

| Hospital stays (days) | 8.0 (7.0-11.0) | 9.0 (7.8-12.0) | 0.3857 | 8.0 (7.0-11.0) | 9.0 (7.8-10.5) | 0.5055 |

In the de novo group, compared with the R-LR group, patients treated with RIO-RFA had lower platelet counts [127500.0 (97250.0-156500.0) vs 169000.0 (135000.0-215000.0), P = 0.018], smaller maximum tumor size [1.6 (1.5-2.3) cm vs 3.0 (1.8-4.5) cm, P = 0.034], a higher proportion of multiple tumors (> 1 tumor: 3/8 vs 10/49, P = 0.005), shorter operation times [104.0 (68.8-128.8) minutes vs 175.0 (155.0-249.0) minutes, P < 0.001], and less blood loss [10.0 (10.0-10.0) mL vs 350.0 (105.0-805.0) mL, P < 0.001]. After PS matching, no statistically significant differences were observed between R-LR and RIO-RFA in the de novo group.

In the first recurrence group, compared with the R-LR group, patients treated with RIO-RFA had significantly less intraoperative blood loss [10.0 (10.0-55.0) mL vs 175.0 (77.5-326.2) mL, P = 0.005). After PS matching, this difference in blood loss remained significant [10.0 (10.0-55.0) mL vs 175.0 (10.0-266.2) mL, P = 0.017], and the RIO-RFA group exhibited a significantly larger aggregate tumor size compared with the R-LR group [3.3 (2.4-5.3) cm vs 1.9 (1.6-2.7) cm, P = 0.018].

Postoperative complications were graded using the Clavien-Dindo classification, which ranges from grade I (minor, no intervention required) to grade V (death). In this study, complications were defined as Clavien-Dindo grade II-V. A total of 19 patients developed postoperative complications, including one (12.5%) in the RIO-RFA group and 11 (22.4%) in the R-LR group of the de novo HCC group, and five (31.2%) in the RIO-RFA group and two (10.0%) in the R-LR group of the recurrent HCC group. Reported complications included ascites, infection, drug allergy, duodenal ulcer bleeding, liver abscess, and multi-organ dysfunction with hepatorenal syndrome.

In the de novo group, R-LR patients experienced nine cases of ascites (one death at 2 months; others OS 12-89 months), one infection (OS 23 months), and one drug allergy (death at 13 months), while the single RIO-RFA case had ascites (death at 18 months). In the recurrent group, R-LR patients had one case of ascites (OS 61 months) and one duodenal ulcer bleed (death at 55 months). RIO-RFA patients experienced two cases of ascites (one death at 2 months, one OS 41 months), one liver abscess (death at 18 months), one combined ascites and liver abscess (death at 4 months), and one case of multi-organ dysfunction with hepatorenal syndrome (death at 1 month). These findings suggest that severe complications were associated with early mortality, particularly among patients in the recurrent HCC group treated with RIO-RFA.

Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to assess prognostic factors influencing long-term survival and HCC recurrence. Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS in the de novo and first recurrence HCC groups are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively, while Tables 5 and 6 summarize the corresponding analyses for RFS. In multivariate analysis, gender was identified as an independent predictor of worse postoperative OS before PS matching (P = 0.046; Table 3); however, this association was not observed after PS matching. No significant prognostic factors for RFS were identified in either group, before or after PS matching, apart from gender. However, this finding is likely biased, given that few female patients were included in first recurrence group (female/male: 6/30).

| Variable | Before PS matching (n = 57) | After PS matching (n = 16) | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Treatment | 0.61 (0.18-2.14) | 0.443 | 0.58 (0.10-3.47) | 0.548 | ||||

| Age | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) | 0.193 | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 0.150 | 1.15 (0.97-1.37) | 0.107 | 1.63 (0.74-3.56) | 0.224 |

| Gender | 2.55 (1.00-6.49) | 0.050 | 4.98 (1.03-24.06) | 0.046 | 0.57 (0.06-5.12) | 0.613 | ||

| HBV | 0.83 (0.32-2.15) | 0.706 | 0.81 (0.13-4.89) | 0.818 | ||||

| HCV | 0.70 (0.23-2.13) | 0.528 | 0.36 (0.04-3.27) | 0.363 | ||||

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 0.62 (0.20-1.89) | 0.403 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.995 | ||||

| Platelet | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.458 | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.988 | ||||

| Prothrombin time | 1.09 (0.74-1.59) | 0.674 | 2.80 (0.69-11.37) | 0.151 | 6.42 (0.17-249.92) | 0.319 | ||

| AST | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.973 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.772 | ||||

| ALT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.869 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.594 | ||||

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 1.15 (0.33-3.99) | 0.823 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.996 | ||||

| Bilirubin total | 0.48 (0.09-2.71) | 0.409 | 0.30 (0.00-22.14) | 0.584 | ||||

| Albumin | 0.55 (0.20-1.53) | 0.252 | 0.12 (0.01-1.48) | 0.098 | 31.48 (0.00-3.6 × 109) | 0.716 | ||

| ALBI | 1.56 (0.51-4.73) | 0.435 | 6.28 (0.86-45.89) | 0.07 | 30.75 (0.00-8.2 × 106) | 0.591 | ||

| Child-Pugh | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.996 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.996 | ||||

| T stage | 1.23 (0.62-2.42) | 0.554 | 0.54 (0.09-3.09) | 0.489 | ||||

| Major tumor size | 1.18 (0.97-1.44) | 0.106 | 1.40 (0.53-3.70) | 0.497 | 1.64 (0.58-4.62) | 0.346 | ||

| Aggregate tumor size | 1.16 (0.96-1.42) | 0.132 | 0.95 (0.38-2.37) | 0.905 | 1.28 (0.46-3.62) | 0.638 | ||

| Tumor numbers | 0.88 (0.34-2.32) | 0.800 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.996 | ||||

| BCLC | 1.59 (0.72-3.49) | 0.249 | 0.71 (0.15-3.42) | 0.67 | ||||

| SAS | 0.95 (0.38-2.41) | 0.917 | 2.26 (0.38-13.60) | 0.373 | ||||

| Complication | 1.07 (0.31-3.72) | 0.911 | 6.28 (0.86-45.89) | 0.07 | 0.05 (0.00-2.7 × 1012) | 0.853 | ||

| Variable | Before PS matching (n = 36) | After PS matching (n = 32) | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Treatment | 0.13 (0.02-0.66) | 0.014 | 1.15 (0.01-264.01) | 0.960 | 0.16 (0.03-0.83) | 0.029 | 0.92 (0.00-299.08) | 0.977 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.95-1.07) | 0.886 | 1.01 (0.95-1.08) | 0.782 | ||||

| Gender | 0.54 (0.07-4.30) | 0.556 | 0.54 (0.07-4.38) | 0.565 | ||||

| HBV | 1.26 (0.31-5.08) | 0.742 | 1.62 (0.40-6.51) | 0.498 | ||||

| HCV | 0.67 (0.14-3.22) | 0.614 | 0.53 (0.11-2.59) | 0.436 | ||||

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 1.82 (0.49-6.80) | 0.373 | 3.35 (0.88-12.70) | 0.076 | 100.80 (0.28-36753.83) | 0.125 | ||

| Platelet | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.514 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.872 | ||||

| Prothrombin time | 1.60 (1.11-2.30) | 0.011 | 16.45 (0.51-528.83) | 0.114 | 1.55 (1.09-2.20) | 0.015 | 3.06 (0.10-93.96) | 0.522 |

| AST | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.127 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.970 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.180 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.643 |

| ALT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.955 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.882 | ||||

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 2.36 (0.63-8.84) | 0.203 | 2.41 (0.64-9.01) | 0.191 | 1.65 (0.07-36.92) | 0.753 | ||

| Bilirubin total | 1.15 (0.24-5.58) | 0.861 | 0.97 (0.19-5.03) | 0.970 | ||||

| Albumin | 0.41 (0.12-1.38) | 0.150 | 26.60 (0.34-2088.41) | 0.141 | 0.41 (0.13-1.25) | 0.115 | 7.23 (0.07-799.58) | 0.410 |

| ALBI | 1.18 (0.25-5.71) | 0.834 | 1.31 (0.27-6.34) | 0.738 | ||||

| Child-Pugh | 2.08 (0.43-10.07) | 0.362 | 1.77 (0.37-8.54) | 0.479 | ||||

| T stage | 3.79 (1.16-12.31) | 0.027 | 0.09 (0.00-4.55) | 0.225 | 3.87 (1.22-12.25) | 0.021 | 0.31 (0.01-18.91) | 0.577 |

| Major tumor size | 1.35 (0.83-2.20) | 0.228 | 1.51 (0.93-2.43) | 0.095 | 3.89 (0.07-211.13) | 0.505 | ||

| Aggregate tumor size | 1.30 (1.05-1.61) | 0.016 | 1.57 (0.70-3.56) | 0.276 | 1.32 (1.08-1.61) | 0.007 | 1.33 (0.38-4.66) | 0.652 |

| Tumor numbers | 1.70 (0.99-2.91) | 0.055 | 4.65 (0.77-27.97) | 0.093 | 1.62 (0.95-2.76) | 0.076 | 12.29 (0.28-534.39) | 0.192 |

| BCLC | 2.87 (0.88-9.38) | 0.082 | 26.75 (0.89-803.48) | 0.058 | 3.70 (1.10-12.41) | 0.034 | 0.99 (0.00-395.47) | 0.997 |

| SAS | 0.80 (0.20-3.20) | 0.749 | 1.00 (0.25-4.01) | 0.998 | ||||

| Complication | 7.29 (1.94-27.33) | 0.003 | 142.17 (0.37-55319.72) | 0.103 | 6.14 (1.64-23.03) | 0.007 | 0.42 (0.00-83.99) | 0.750 |

| Variable | Before PS matching (n = 57) | After PS matching (n = 16) | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Treatment | 1.34 (0.41-4.43) | 0.631 | 1.45 (0.32-6.52) | 0.626 | ||||

| Age | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 0.441 | 1.14 (1.00-1.29) | 0.056 | 1.04 (0.81-1.32) | 0.769 | ||

| Gender | 1.17 (0.55-2.47) | 0.679 | 0.29 (0.03-2.40) | 0.249 | ||||

| HBV | 0.50 (0.24-1.04) | 0.064 | 0.52 (0.24-1.11) | 0.090 | 0.20 (0.04-0.95) | 0.042 | 0.06 (0.00-1.45) | 0.084 |

| HCV | 1.38 (0.63-3.03) | 0.415 | 2.03 (0.45-9.18) | 0.356 | ||||

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 0.48 (0.20-1.18) | 0.109 | 0.73 (0.27-1.99) | 0.533 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.994 | ||

| Platelet | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.050 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.516 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.778 | 1.12 (0.08-15.00) | 0.930 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.85 (1.06-3.23) | 0.031 | 1.31 (0.77-2.25) | 0.319 | 3.92 (0.97-15.91) | 0.056 | ||

| AST | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.526 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.917 | ||||

| ALT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.639 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.973 | ||||

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 0.69 (0.24-1.99) | 0.493 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.994 | ||||

| Bilirubin total | 3.31 (0.74-14.89) | 0.118 | 2.44 (0.42-14.28) | 0.321 | 7.55 (0.24-234.20) | 0.249 | ||

| Albumin | 0.47 (0.20-1.09) | 0.079 | 0.65 (0.25-1.71) | 0.383 | 0.44 (0.07-2.81) | 0.389 | ||

| ALBI | 1.70 (0.69-4.18) | 0.249 | 2.08 (0.40-10.81) | 0.383 | ||||

| Child-Pugh | 0.95 (0.13-7.01) | 0.962 | 0.00 (0.00-inf) | 0.995 | ||||

| T stage | 0.96 (0.52-1.77) | 0.899 | 0.74 (0.24-2.28) | 0.602 | ||||

| Major tumor size | 1.05 (0.89-1.25) | 0.539 | 1.11 (0.49-2.54) | 0.802 | ||||

| Aggregate tumor size | 1.06 (0.90-1.25) | 0.457 | 1.15 (0.50-2.66) | 0.747 | ||||

| Tumor numbers | 1.11 (0.60-2.04) | 0.740 | 0.59 (0.14-2.56) | 0.479 | ||||

| BCLC | 1.09 (0.60-1.97) | 0.786 | 0.51 (0.13-1.92) | 0.316 | ||||

| SAS | 1.73 (0.84-3.55) | 0.137 | 1.25 (0.57-2.75) | 0.574 | 4.70 (0.90-24.48) | 0.066 | 0.94 (0.04-22.31) | 0.972 |

| Complication | 0.67 (0.23-1.93) | 0.459 | 2.08 (0.40-10.81) | 0.383 | ||||

| Variable | Before PS matching (n = 36) | After PS matching (n = 32) | ||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Treatment | 0.32 (0.13-0.81) | 0.016 | 0.29 (0.09-0.97) | 0.043 | 0.39 (0.15-1.00) | 0.051 | 0.46 (0.13-1.61) | 0.226 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.586 | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 0.847 | ||||

| Gender | 2.77 (0.97-7.95) | 0.058 | 6.60 (1.79-24.32) | 0.004 | 3.22 (1.12-9.28) | 0.030 | 6.81 (1.98-23.41) | 0.002 |

| HBV | 0.61 (0.25-1.47) | 0.267 | 0.74 (0.30-1.82) | 0.508 | ||||

| HCV | 1.04 (0.40-2.72) | 0.937 | 0.88 (0.33-2.33) | 0.795 | ||||

| ICG-R15 < 10% | 1.22 (0.48-3.07) | 0.675 | 2.42 (0.88-6.66) | 0.088 | 1.33 (0.37-4.84) | 0.660 | ||

| Platelet | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.137 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.129 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.321 | ||

| Prothrombin time | 1.35 (0.95-1.92) | 0.098 | 1.21 (0.88-1.66) | 0.235 | 1.29 (0.90-1.87) | 0.167 | 1.28 (0.91-1.80) | 0.153 |

| AST | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.418 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.672 | ||||

| ALT | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.74 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.782 | ||||

| AFP ≥ 100 ng/mL | 2.09 (0.82-5.32) | 0.12 | 2.60 (0.72-9.44) | 0.145 | 2.69 (1.04-6.97) | 0.041 | 2.08 (0.54-8.01) | 0.285 |

| Bilirubin total | 1.72 (0.63-4.70) | 0.293 | 1.26 (0.43-3.70) | 0.675 | ||||

| Albumin | 0.69 (0.24-1.98) | 0.491 | 0.63 (0.23-1.73) | 0.369 | ||||

| ALBI | 1.44 (0.52-3.97) | 0.482 | 1.28 (0.42-3.88) | 0.66 | ||||

| Child-Pugh | 1.32 (0.38-4.53) | 0.658 | 1.15 (0.33-3.98) | 0.824 | ||||

| T stage | 1.36 (0.60-3.08) | 0.455 | 1.34 (0.59-3.04) | 0.482 | ||||

| Major tumor size | 1.01 (0.67-1.53) | 0.951 | 1.08 (0.68-1.71) | 0.743 | ||||

| Aggregate tumor size | 1.08 (0.89-1.32) | 0.436 | 1.12 (0.93-1.35) | 0.214 | ||||

| Tumor numbers | 1.30 (0.85-1.98) | 0.224 | 1.30 (0.87-1.95) | 0.202 | ||||

| BCLC | 1.08 (0.50-2.31) | 0.843 | 1.41 (0.64-3.14) | 0.397 | ||||

| SAS | 0.74 (0.29-1.85) | 0.514 | 1.02 (0.40-2.60) | 0.967 | ||||

| Complication | 4.20 (1.65-10.70) | 0.003 | 3.62 (1.09-11.96) | 0.034 | 3.78 (1.46-9.75) | 0.006 | 3.08 (0.76-12.44) | 0.114 |

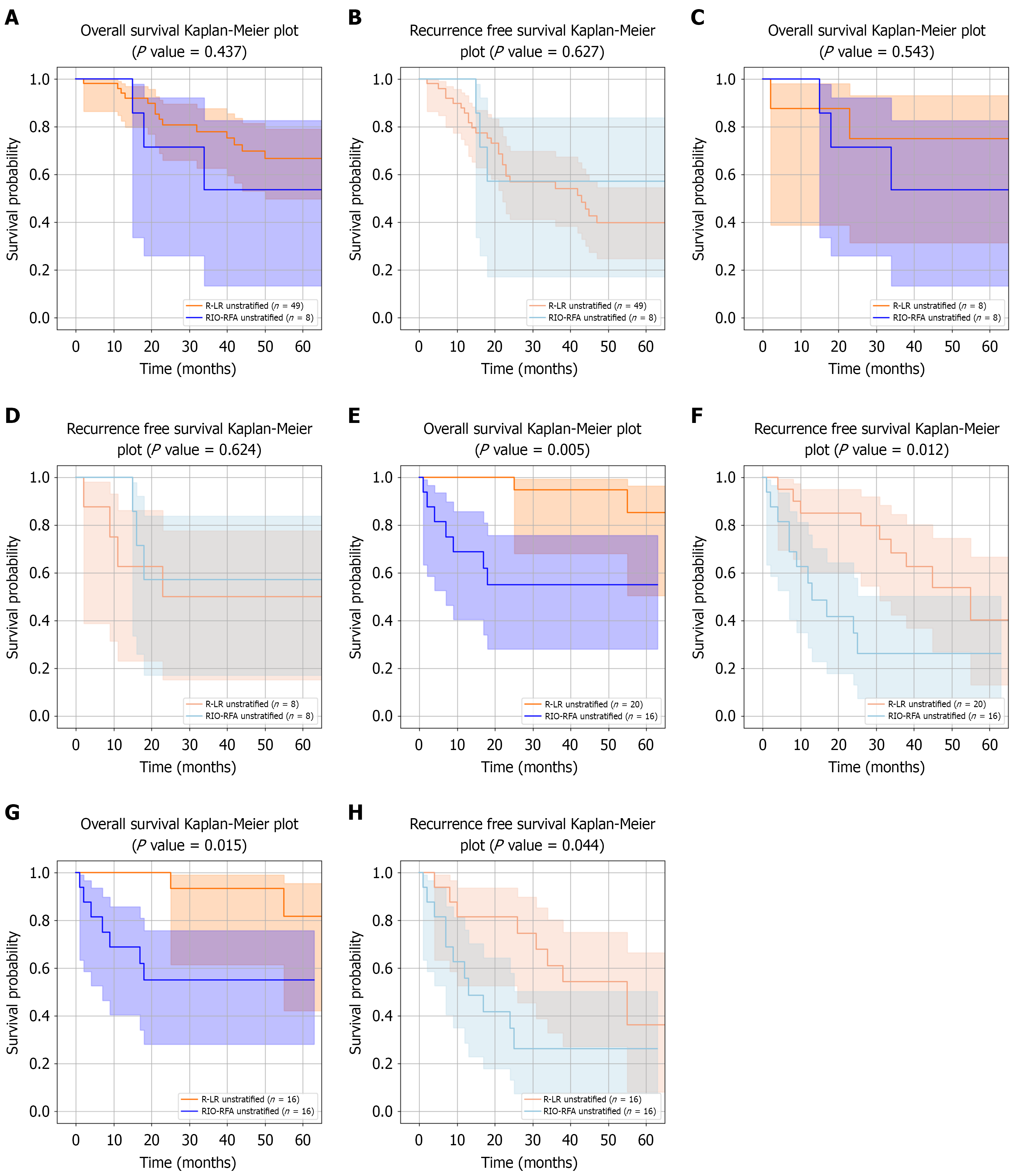

De novo HCC group: The Figure 3A-D shows Kaplan-Meier curves for OS and RFS in patients treated with R-LR or RIO-RFA, analyzed both before and after PS matching. No significant differences in OS or RFS were observed between the two groups in either analysis. The median follow-up durations were 44.0 months (IQR 22.0-69.0) in the R-LR group and 30.0 months (IQR 17.2-46.8) in the RIO-RFA group, increasing to 52.5 months (IQR 27.5-78.0) for R-LR after PS matching. OS rates at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were 93.9%, 79.6%, and 71.4% for R-LR (87.5%, 75.0%, and 75.0% after PS matching), compared with 100%, 62.5%, and 62.5% for RIO-RFA. The corresponding RFS rates were 14.3%, 42.9%, and 53.1% for R-LR (37.5%, 50.0%, and 50.0% after PS matching), compared with 0%, 37.5%, and 37.5% for RIO-RFA. RMST analysis showed no significant OS differences between the two groups across multiple time horizons. For RFS, RMST differences were also not significant across truncation times, except at 1 year before PS matching. Detailed RMST analyses of OS and RFS in the de novo HCC group are presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1.

First recurrence HCC group:Figure 3E-H shows Kaplan-Meier curves for OS and RFS in patients with first recurrent HCC. In contrast to the de novo group, significant differences were observed between the two treatment groups for both OS (P = 0.005) and RFS (P = 0.012). The median follow-up durations were 52.0 months (IQR 40.8-68.2) in the R-LR group and 21.0 months (IQR 8.5-41.0) in the RIO-RFA group, remaining 52.0 months (IQR 40.8-68.2) for R-LR after PS matching. OS rates at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were 100%, 95.0%, and 90.0% for R-LR (100%, 93.8%, and 87.5% after PS matching), compared with 68.8%, 56.2%, and 56.2% for RIO-RFA. RFS rates at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years were 15.0%, 30.0%, and 45.0% for R-LR (18.8%, 37.5%, and 50.0% after PS matching), compared with 43.8%, 68.8%, and 68.8% for RIO-RFA.

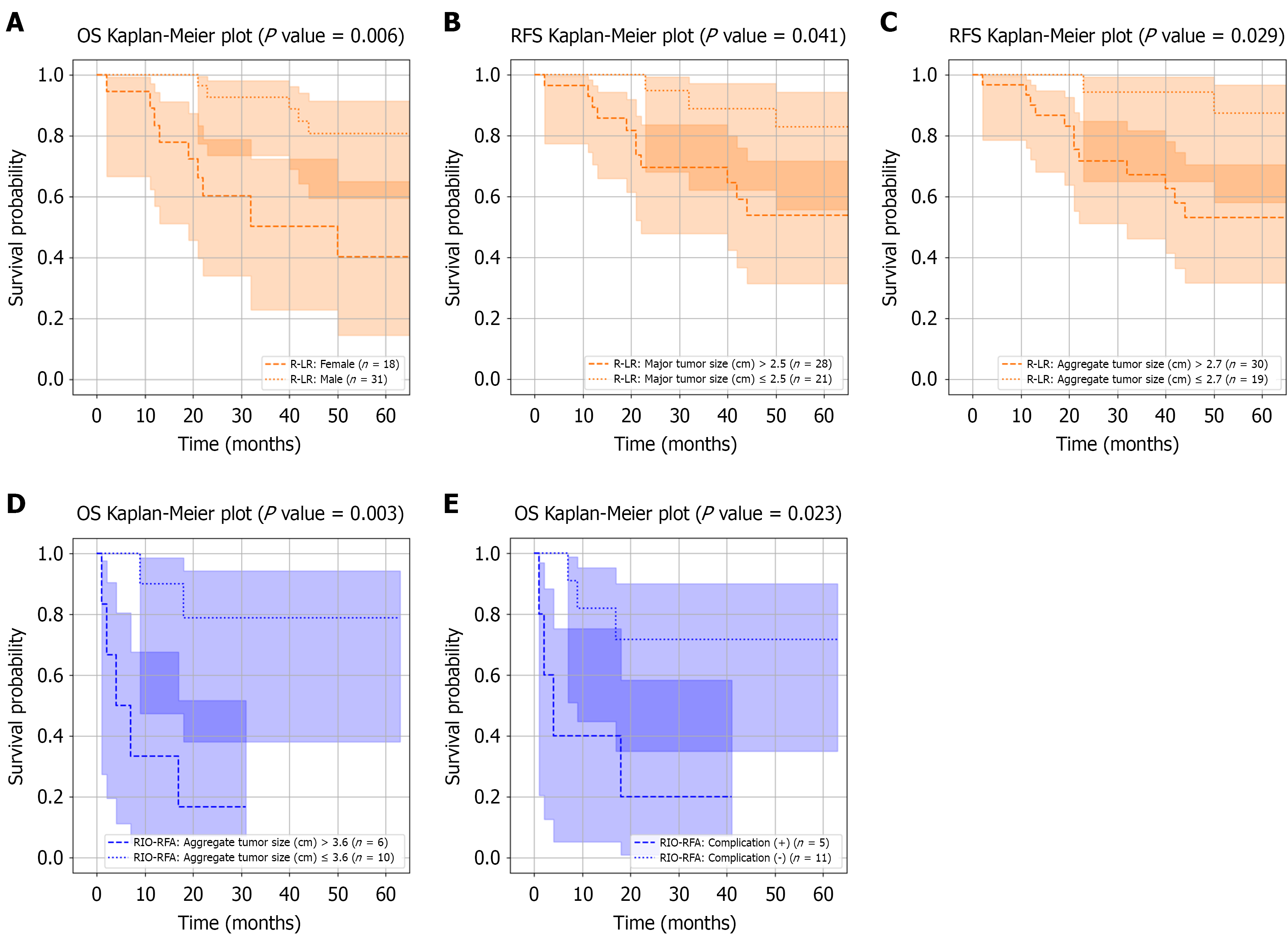

In the de novo HCC group, subgroup analysis after PS matching was not feasible due to the limited number of RIO-RFA cases (n = 8). Without matching, significant OS differences between low-risk and high-risk subgroups were observed within the R-LR group, stratified by gender, major tumor size (cut-off: 1.8 cm), and aggregate tumor size (cut-off: 2.7 cm), with log-rank P values of 0.006, 0.028, and 0.029, respectively (Figure 4A-C). Table 7 presents Kaplan-Meier comparisons of low-risk and high-risk R-LR subgroups against the RIO-RFA group and the original unstratified R-LR group. Patients in the low-risk R-LR subgroup, defined by smaller major tumor size (P = 0.011) and smaller aggregate tumor size (P = 0.036), demonstrated superior OS compared with RIO-RFA. By contrast, no significant survival differences were observed between R-LR and RIO-RFA in the unstratified analysis (Figure 3A-D).

| Gender | Major tumor size | Aggregate tumor size | |

| Low risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.208 | 0.079 | 0.139 |

| High risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.069 | 0.370 | 0.281 |

| Low risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.068 | 0.011 | 0.036 |

| High risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.595 | 0.867 | 0.971 |

In first recurrence HCC group, subgroup analysis was performed for both R-LR and RIO-RFA before and after PS matching; however, only the post-matching results are presented. Significant OS differences were identified within the RIO-RFA group based on aggregate tumor size and postoperative complications (P = 0.003 and P = 0.023, respectively; Figure 4D and E). Low-risk RIO-RFA patients (smaller tumors or absence of complications) achieved OS comparable to R-LR (Table 8), whereas the unstratified RIO-RFA group demonstrated inferior survival compared with R-LR (Figure 3E-H). Detailed Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors associated with long-term OS in high-risk and low-risk subgroups from each group are provided in Supplementary Tables 1-4.

| Aggregate tumor size | Complication | |

| Low risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.320 | 0.145 |

| High risk vs unstratified R-LR | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Low risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.188 | 0.357 |

| High risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.057 | 0.122 |

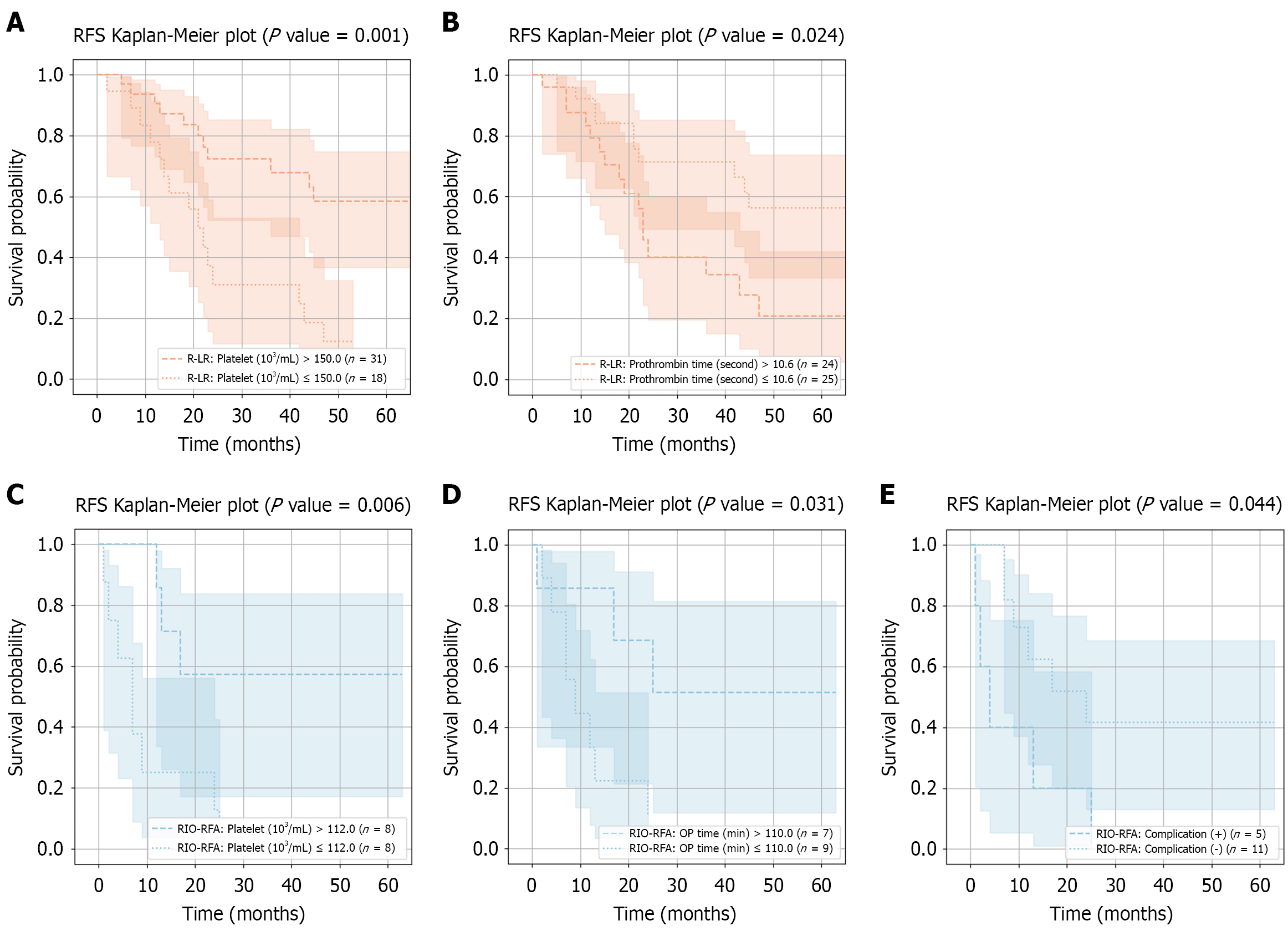

Similar to OS, subgroup analysis after PS matching was not performed in the de novo HCC group. Without matching, significant RFS differences between low- and high-risk subgroups within the R-LR group were observed for platelet count and prothrombin time, with log-rank P values of 0.001 and 0.024, respectively (Figure 5A and B). High-risk R-LR patients with lower platelet counts had worse RFS compared with the unstratified R-LR group (P = 0.029; Table 9), although no differences were observed between unstratified R-LR and RIO-RFA groups (Figure 3A-D).

| Platelet | Prothrombin time | |

| Low risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.151 | 0.232 |

| High risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.029 | 0.171 |

| Low risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.718 | 0.805 |

| High risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.106 | 0.240 |

In first recurrence HCC group, only the post-PS matching subgroup analysis results are presented. No significant RFS differences were observed between low- and high-risk subgroups within the R-LR group. In contrast, patients in the low-risk RIO-RFA subgroup - defined by higher platelet count, longer operative time, or absence of postoperative complications - achieved RFS comparable to R-LR, with log-rank P values of 0.006, 0.031, and 0.044, respectively (Figure 5C-E). Low-risk RIO-RFA patients with higher platelet count, longer operative time, or absence of complications had comparable RFS compared with R-LR (Table 10), whereas significant survival differences (P = 0.012) were observed between unstratified R-LR and RIO-RFA (Figure 3E-H). Detailed Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors associated with long-term RFS in high-risk and low-risk subgroups from each group are provided in Supplementary Tables 5-8.

| Platelet | OP time | Complication | |

| Low risk vs unstratified R-LR | 0.971 | 0.844 | 0.343 |

| High risk vs unstratified R-LR | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Low risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.143 | 0.216 | 0.428 |

| High risk vs unstratified RIO-RFA | 0.090 | 0.230 | 0.159 |

Laparoscopic surgery has been reported to yield better outcomes than RFA for single small subcapsular HCCs[15], but other studies have found no significant survival difference between repeat resection and RFA for tumors in subcapsular locations[16]. The optimal treatment strategy remains uncertain, particularly for lesions located near the diaphragmatic dome or in perivascular regions[17]. In this context, the present study focused on HCC located in liver segments VII and VIII - areas considered technically challenging for liver surgery - and utilized robotic approaches to compare OS and RFS between R-LR and RIO-RFA in both de novo and first recurrent HCC groups. After PS matching, baseline characteristics were balanced between the two treatment groups in both groups, with the exception of intraoperative blood loss in the first-recurrent HCC group.

In the de novo HCC group, no significant differences in OS or RFS were observed between R-LR and RIO-RFA, either before or after PS matching. This finding is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, which reported no significant difference in OS between liver resection and RFA for solitary HCC[18]. By contrast, in the first recurrent HCC group, both OS and RFS were significantly different between treatment groups in the present study. OS results align with several meta-analyses and systematic reviews that concluded liver resection confers superior long-term survival compared with RFA for recurrent HCC, despite the latter being associated with a more favorable safety profile[19,20]. RFS results also consistent with previous studies. A systematic review with meta-analyses reported that liver resection provides a significant long-term survival advantage over RFA for recurrent HCC[21], while a retrospective multicenter study similarly demonstrated superior RFS with liver resection[22].

Subgroup analyses provided further insights. In the de novo HCC group, low-risk patients within the R-LR group, defined by smaller major tumor size (≤ 1.8 cm) and aggregate tumor size (≤ 2.7 cm), achieved superior OS compared with high-risk subgroup and those treated with RIO-RFA (Figure 4A-C; Table 7). Conversely, in the high-risk R-LR subgroup, patients with lower platelet counts demonstrated worse RFS (Figure 5A and B; Table 9). These findings suggest that R-LR should be considered a preferred treatment option for small HCC, while patients with low platelet counts require closer postoperative monitoring for recurrence. However, subgroup analysis in the de novo group was conducted without PS matching due to the very limited number of RIO-RFA cases. These findings should therefore be regarded as exploratory and potentially influenced by confounding bias.

In first recurrence HCC group, subgroup analyses within the RIO-RFA group revealed that patients classified as low-risk - defined by smaller aggregate tumor size (≤ 3.6 cm) or absence of postoperative complications - achieved comparable OS with those treated with R-LR (Figure 4D and E; Table 8). The findings highlight tumor size and postoperative complications as critical factors when determining the optimal treatment strategy for the first recurrent HCC. Additionally, low-risk RIO-RFA patients with higher platelet counts or no complications achieved RFS outcomes comparable to R-LR (Figure 5C-E; Table 10). Consistent with the RFS results observed in the de novo group, these findings underscore platelet counts and postoperative complications as key prognostic factors for recurrence in HCC.

Our findings show that in de novo HCC, R-LR and RIO-RFA achieved comparable survival outcomes before and after PS matching, although R-LR conferred superior outcomes in patients with smaller tumors. In contrast, in the recurrent HCC group, R-LR was associated with significantly better OS and RFS, likely reflecting more complete tumor clearance and reduced local recurrence, a known limitation of RFA, particularly for the residual HCC and those located deeper and near blood vessels[22,23]. However, the comparable outcomes of RIO-RFA in selected low-risk patients suggest that careful patient selection can mitigate some of these limitations. Tumor size, platelet count, and postoperative complications emerged as key prognostic factors for guiding individualized treatment. Thrombocytopenia may reflect more advanced portal hypertension or impaired hepatic reserve, conditions known to influence recurrence risk and long-term outcomes[24]. Similarly, postoperative complications not only delay adjuvant therapy or surveillance but may also reflect underlying patient frailty[25].

Based on the BCLC staging system, patients with early-stage HCC (stages 0 and A) are recommended for surgical resection or RFA[26]. For patients with BCLC B and BCLC C disease and preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A), newly developed systemic targeted agents and combination therapies have become available and may influence treatment decisions, although their role in BCLC B patients with Child-Pugh B remains uncertain[27]. In parallel, there is a growing trend - particularly in Asian countries - to extend the indications for surgical resection to selected patients with intermediate-stage HCC. More recent evidence has further supported expanding resection to both intermediate and advanced stages, demonstrating improved long-term survival compared with conventional palliative approaches[28-30]. Overall, our study provides additional evidence supporting the role of surgical resection and RFA in technically challenging tumor locations (segments VII and VIII) for both de novo and recurrent HCC, our findings contribute to the evolving landscape of HCC management within the BCLC framework and emphasize the importance of tailoring treatment strategies to individual patient profiles.

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design introduces potential selection bias, although we attempted to mitigate this through PS matching. Second, the relatively small number of patients in the RIO-RFA subgroup, particularly in the de novo group (n = 8), limited the statistical power even after PS matching. Future multi-center studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm and extend these results. Third, all patients were from a single institution, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings. Fourth, while we focused on segments VII and VIII to address a clinically relevant challenge, our results may be different to HCCs in other liver segments. Fifth, this study focused exclusively on R-LR and RIO-RFA. We did not include comparisons with conventional laparoscopic or open liver resections, which limits the generalizability of our findings to broader clinical practice. Sixth, although our RFA protocol was standardized with respect to power output, ablation margin, and electrode type, we did not specifically analyze the impact of these technical parameters on treatment outcomes. Given that ablation margin and energy delivery are known to be critical predictors of local tumor control, further research should investigate their role in determining therapeutic efficacy.

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the comparative efficacy of R-LR and RIO-RFA in a technically challenging anatomical setting. Future prospective multicenter studies with larger groups are warranted to validate these findings and to refine patient selection criteria for individualized treatment strategies.

For HCC located in segments VII and VIII, R-LR and RIO-RFA provided comparable survival outcomes in the de novo group, whereas R-LR achieved superior OS and RFS in the first recurrent group. Subgroup analyses indicate that R-LR is preferable for small de novo tumors, while RIO-RFA may represent a reasonable alternative in carefully selected low-risk patients with recurrent disease. Platelet count, tumor size, and postoperative complications emerged as key prognostic factors and should be incorporated into individualized treatment planning and postoperative surveillance strategies. Our study provides additional evidence supporting the role of surgical resection and RFA in technically challenging tumors of segments VII and VIII for both de novo and recurrent HCC, contributing to the evolving landscape of HCC management within the BCLC framework and underscoring the importance of individualized treatment strategies.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. [cited 2025 September 6]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/11-liver-and-intrahepatic-bile-ducts-fact-sheet.pdf. |

| 2. | Choi JH, Thung SN. Advances in Histological and Molecular Classification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singal AG, Kanwal F, Llovet JM. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:864-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 178.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Wang L, Liu BX, Long HY. Ablative strategies for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:515-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Linn YL, Wu AG, Han HS, Liu R, Chen KH, Fuks D, Soubrane O, Cherqui D, Geller D, Cheung TT, Edwin B, Aldrighetti L, Abu Hilal M, Troisi RI, Wakabayashi G, Goh BKP; International Robotic and Laparoscopic Liver Resection Study Group Investigators. Systematic review and meta-analysis of difficulty scoring systems for laparoscopic and robotic liver resections. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023;30:36-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berardi G, Muttillo EM, Colasanti M, Mariano G, Meniconi RL, Ferretti S, Guglielmo N, Angrisani M, Lucarini A, Garofalo E, Chiappori D, Di Cesare L, Vallati D, Mercantini P, Ettorre GM. Challenging Scenarios and Debated Indications for Laparoscopic Liver Resections for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rhim H, Lim HK, Kim YS, Choi D. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation with artificial ascites for hepatocellular carcinoma in the hepatic dome: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee MW, Kim YJ, Park SW, Jeon HJ, Yi JG, Choe WH, Kwon SY, Lee CH. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of liver dome hepatocellular carcinoma invisible on ultrasonography: a new targeting strategy. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e130-e134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hsieh CL, Peng CM, Chen CW, Liu CH, Teng CT, Liu YJ. Benefits and drawbacks of radiofrequency ablation via percutaneous or minimally invasive surgery for treating hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:3400-3407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang Y, Song J, Zheng J, Jiang L, Yan L, Yang J, Zeng Y, Wu H. Comparison of Hepatic Resection Combined with Intraoperative Radiofrequency Ablation, or Hepatic Resection Alone, for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with Multifocal Tumors Meeting the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Criteria: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:2334-2345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zheng K, Liao A, Yan L, Yang J, Wen T, Wang W, Li B, Wu H, Jiang L. Hepatic Resection Combined with Intraoperative Radiofrequency Ablation Versus Hepatic Resection Alone for Selected Patients with Moderately Advanced Multifocal Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:5189-5201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hu L, Lin J, Wang A, Shi X, Qiao Y. Comparison of liver resection and radiofrequency ablation in long-term survival among patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and high-quality propensity score-matched studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jiang YQ, Wang ZX, Deng YN, Yang Y, Wang GY, Chen GH. Efficacy of Hepatic Resection vs Radiofrequency Ablation for Patients With Very-Early-Stage or Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Population-Based Study With Stratification by Age and Tumor Size. Front Oncol. 2019;9:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang YQ, Tan ZK, Peng Z, Huang H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparison of laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation to percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1559343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin CH, Ho CM, Wu CH, Liang PC, Wu YM, Hu RH, Lee PH, Ho MC. Minimally invasive surgery versus radiofrequency ablation for single subcapsular hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 2 cm with compensated liver cirrhosis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:5566-5573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wei F, Huang Q, Zhou Y, Luo L, Zeng Y. Radiofrequency ablation versus repeat hepatectomy in the treatment of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in subcapsular location: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hsiao CY, Hu RH, Liang PC, Wu CH. Comparison of Long-Term Outcomes Between Repeated Hepatic Resection and Radiofrequency Ablation in Patients with Small Recurrent Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Initial Curative Resection: A Propensity Score Matched Study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2025;12:1587-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang M, Li G, Chen K, Wu Y, Sun T, Wang W. Liver resection versus radiofrequency ablation for solitary small hepatocellular carcinoma measuring ≤3 cm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:3456-3466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang Y, Qin Y, Dong P, Ning H, Wang G. Liver resection, radiofrequency ablation, and radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for very-early- and early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis for comparison of efficacy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:991944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Machairas N, Papaconstantinou D, Dorovinis P, Tsilimigras DI, Keramida MD, Kykalos S, Schizas D, Pawlik TM. Meta-Analysis of Repeat Hepatectomy versus Radiofrequency Ablation for Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yang Y, Yu H, Tan X, You Y, Liu F, Zhao T, Qi J, Li J, Feng Y, Zhu Q. Liver resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2021;38:875-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhong JH, Xing BC, Zhang WG, Chan AW, Chong CCN, Serenari M, Peng N, Huang T, Lu SD, Liang ZY, Huo RR, Wang YY, Cescon M, Liu TQ, Li L, Wu FX, Ma L, Ravaioli M, Neri J, Cucchetti A, Johnson PJ, Li LQ, Xiang BD. Repeat hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective multicentre study. Br J Surg. 2021;109:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu S, Li Z, Yao C, Dong S, Gao J, Ke S, Zhu R, Huang S, Wang S, Xu L, Ye C, Kong J, Sun W. Progression of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation: Current status of research. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1032746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Maithel SK, Kneuertz PJ, Kooby DA, Scoggins CR, Weber SM, Martin RC 2nd, McMasters KM, Cho CS, Winslow ER, Wood WC, Staley CA 3rd. Importance of low preoperative platelet count in selecting patients for resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:638-48; discussion 648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chok KS, Ng KK, Poon RT, Lo CM, Fan ST. Impact of postoperative complications on long-term outcome of curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 3151] [Article Influence: 787.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (61)] |

| 27. | Torimura T, Iwamoto H. Optimizing the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: Current trends and prospects. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:236-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhaohui Z, Shunli S, Bin C, Shaoqiang L, Yunpeng H, Ming K, Lijian L, Gang PB. Hepatic Resection Provides Survival Benefit for Selected Intermediate-Stage (BCLC-B) Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lopez-Lopez V, Kalt F, Zhong JH, Guidetti C, Magistri P, Di Benedetto F, Weinmann A, Mittler J, Lang H, Sharma R, Vithayathil M, Tariq S, Sánchez-Velázquez P, Rompianesi G, Troisi RI, Gómez-Gavara C, Dalmau M, Sanchez-Romero FJ, Llamoza C, Tschuor C, Deniz U, Lurje G, Husen P, Hügli S, Jonas JP, Rössler F, Kron P, Ramser M, Ramirez P, Lehmann K, Robles-Campos R, Eshmuminov D. The role of resection in hepatocellular carcinoma BCLC stage B: A multi-institutional patient-level meta-analysis and systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2024;409:277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Guo H, Wu T, Lu Q, Li M, Guo JY, Shen Y, Wu Z, Nan KJ, Lv Y, Zhang XF. Surgical resection improves long-term survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/