Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.113407

Revised: September 22, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 122 Days and 18.6 Hours

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines have been established for multiple types of adult surgeries. However, ERAS guidelines tailored to pediatric surgeries remain to be developed.

To evaluate the clinical outcomes of ERAS protocols in pediatric laparoscopic Meckel’s diverticulum resection.

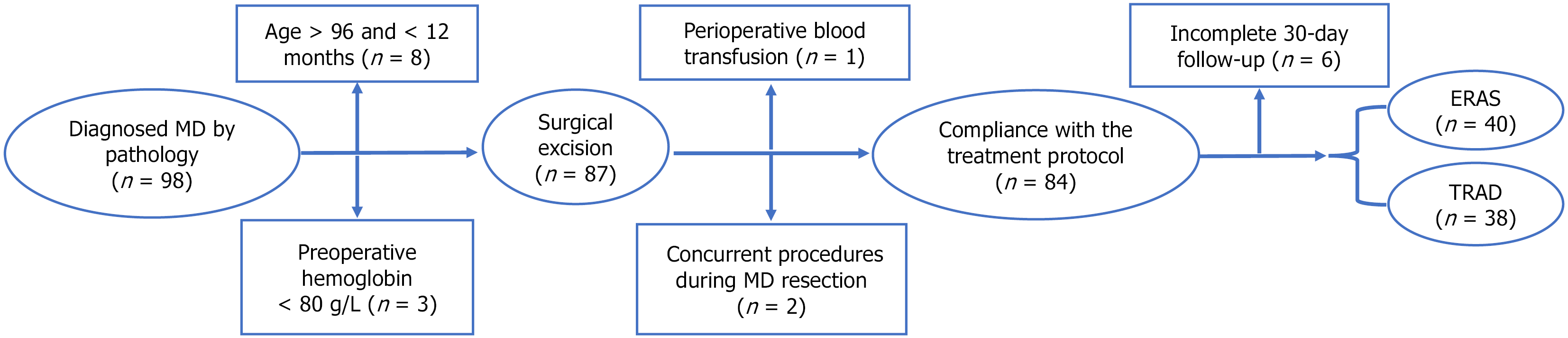

This retrospective cohort study analyzed 78 consecutive pediatric cases treated between January 2017 and March 2025. Patients were divided into: Traditional care group (n = 38): January 2017-December 2020; ERAS protocol group (n = 40): January 2021-March 2025. We compared perioperative outcomes, including clinical recovery parameters and laboratory markers, to assess protocol efficacy.

All procedures were completed laparoscopically by the same surgical team without conversion. Baseline characteristics, including demographics, diverti

ERAS protocols safely optimize recovery in children undergoing laparoscopic Meckel’s diverticulum resection, significantly reducing length of stay while improving pain management and overall clinical outcomes. These findings support the adoption of ERAS in pediatric intestinal surgery.

Core Tip: Our study provides compelling evidence that enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol implementation is both safe and clinically beneficial for young children undergoing laparoscopic resection of Meckel’s diverticulum. Importantly, our subgroup analyses revealed a significant differential response to ERAS implementation based on surgical technique, as evidenced by substantially greater reductions in postoperative length of stay among patients who underwent segmental intestinal resection compared to those receiving wedge resection. These findings underscore the critical importance of tailoring ERAS protocols to specific surgical procedures, with maximal benefits being achieved in more complex resections.

- Citation: Zhu K, Zhang X, Li Y, Gao Y, Tong YM, He JJ, Su YL. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol implementation in pediatric Meckel’s diverticulum resection: A clinical outcome study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 113407

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/113407.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.113407

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), occurring in approximately 2% of the population with a 2-4:1 male predominance, results from incomplete omphalomesenteric duct regression during fetal development[1,2]. While most cases remain asymptomatic, complications requiring surgery (bleeding, obstruction, or diverticulitis) develop in 5%-15% of patients[3]. Laparoscopic resection has become the gold standard approach due to its minimally invasive advantages and faster recovery[4].

The concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) was initially introduced by Danish surgeon Henrik Kehlet in 1997 for colorectal procedures[5], ERAS employs evidence-based, multidisciplinary protocols to minimize surgical stress, reduce complications, and accelerate recovery[6]. While widely adopted in adult surgery with demonstrated efficacy[7-9], pediatric ERAS implementation remains comparatively limited despite growing interest[10,11]. Pediatric populations present unique perioperative challenges: Physiological vulnerabilities (reduced blood volume, immature thermoregulation), heightened nutritional requirements, developmental communication barriers, and immature immune function. These factors complicate postoperative recovery and highlight the need for tailored ERAS protocols. Current evidence gaps underscore the necessity for rigorous studies to establish standardized approaches for this vulnerable demographic[12].

This retrospective study evaluated the safety and efficacy of ERAS protocols vs traditional care group (TRAD) for pediatric laparoscopic MD resection. Key findings are presented below.

This retrospective analysis included 78 pediatric patients undergoing laparoscopic Meckel's diverticulum resection at the Department of Pediatric Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China (January 2017-March 2025). Patients were stratified by perioperative protocol: TRAD group (n = 38): Traditional care (2017-2020), ERAS group (n = 40): ERAS protocol (2021-2025).

Inclusion criteria: Eligible patients met all of the following: (1) Hematochezia with either: Technetium-99m scintigraphy-confirmed ectopic gastric mucosa, or ultrasound findings highly suggestive of MD; (2) Recurrent hematochezia post-conservative treatment, with strong clinical suspicion of MD despite inconclusive imaging; (3) Stable preoperative status (hemoglobin > 80 g/L, hemodynamically stable, and fit for postoperative pediatric surgical care); (4) Laparoscopic-assisted resection with pathological MD confirmation; and (5) Complete perioperative records, including standardized 30 ± 2 days follow-up.

Exclusion criteria: Patients were excluded if they met any of the following: (1) Age > 96 months, or < 12 months; (2) Preoperative septic or hemorrhagic shock; (3) Perioperative blood transfusion; (4) Prior abdominal surgery or concurrent procedures performed during MD resection; and (5) Participation in other trials or noncompliance with the treatment protocol.

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China (Approval No. 2025-RE-385). A consistent team of pediatric surgeons and anesthe

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) of ERAS was systematically organized for this clinical investigation. The core team comprised two attending pediatric surgeons with specialized expertise, two consultant anesthesiologists, two certified operating room nurses, and four registered ward nurses.

To maintain rigorous protocol standardization, we implemented a comprehensive quality assurance framework with three key components: First, all patients in the ERAS cohort received electronic medical record tagging with automated perioperative alerts to guarantee adherence to established recovery pathways. Second, the MDT conducted structured biweekly progress reviews to monitor clinical outcomes and promptly address any protocol variances. Third, an assigned clinical nurse specialist methodically validated daily completion of all ERAS care elements through systematic checklist verification.

Preoperative measures: Preoperative ERAS protocol: (1) Multidisciplinary education: The MDT provided families with personalized counseling on diagnosis, treatment, surgical steps, recovery expectations, and discharge criteria during outpatient visits; (2) Child-centered preparation: Age-appropriate play therapy reduced preoperative anxiety, familiarized children with the hospital setting, and promoted family participation in care; and (3) Surgery-day measures: Morning glycerin enema for bowel preparation; Standard intravenous (IV) cefuroxime (30 mg/kg) 30 minutes pre-incision (both groups); fasting optimization: 6 hours for solids/formula, 4 hours for breast milk, 2 hours for oral 10% glucose (5 mL/kg); nasogastric tubes (NGTs) placed post-induction, selectively removed in post-anesthesia care unit post-awakening[13]. TRAD group protocol: (1) Standard counseling: The attending physician provided a centralized overview of diagnosis, treatment, and postoperative risks; (2) Bowel preparation: Saline enema the night before surgery, glycerin enema on the morning of surgery; (3) Fasting protocol: No preoperative dietary adjustments, mandatory 8-hour fasting (solids/fluids) pre-surgery; and (4) NGTs inserted preoperatively in the ward.

Intraoperative measures: The ERAS group implemented these intraoperative measures: (1) Anesthesia: Combined general endotracheal anesthesia with caudal block; (2) Thermoregulation: Operating room temperature > 25 °C, warming blankets, pre-warmed disinfectants and IV fluids; (3) Fluid Management: Strict titration (heart rate, blood pressure, urine output) to avoid overload[14]; (4) Drainage: Selective use only for: Suspected perforation with contamination, significant turbid peritoneal fluid; and (5) Analgesia: Umbilical incision infiltration with 0.5% ropivacaine[15]. TRAD group: (1) Anesthesia: Standard endotracheal general anesthesia only (no regional blocks required); (2) Temperature/fluid management: Conventional warming measures and fluid replacement based on physiological requirements and estimated losses; and (3) Drainage: Permitted use of abdominal drainage.

The standardized laparoscopic surgical protocol included the following steps: (1) Pneumoperitoneum was established and a systematic bowel examination from ileocecal region proximally to locate lesion. We routinely examined ≥ 100 cm proximal small intestine to rule out multiple MD; (2) The affected segment was clamped and stabilized. Next, the umbilical incision was extended to approximately 2.5 cm for bowel exteriorization; (3) Resection strategy and anastomosis technique: For narrow-based (< 2 cm) without surrounding inflammation, we performed wedge resection at base followed by 45° oblique intestinal wall anastomosis; for broad-based (≥ 2 cm) or complicated cases (diverticulitis/perforation/edema), we conducted segmental resection of involved bowel followed by end-to-end anastomosis with mesenteric closure. All intestinal anastomoses were constructed using continuous inverted 5-0 absorbable sutures with intermittent seromuscular reinforcement[16]; and (4) Closure: We verified bowel patency, repositioned bowel carefully, and layered umbilical incision closure.

Postoperative measures: Both groups received standardized postoperative care comprising: (1) IV cefuroxime sodium prophylaxis for 24 hours postoperatively, with extended antibiotic therapy for perforation cases based on serial infection markers and clinical response; and (2) Protocolized pain assessment using the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) scale at 2-48 hours postoperatively to guide analgesic titration. The ERAS group implemented optimized postoperative care with four key components: (1) A multimodal analgesia protocol was implemented[17], integrating non-pharmacological measures (age-appropriate distraction and 24% sucrose-dipped pacifiers) with scheduled oral acetaminophen or ibuprofen administered every 6 hours. Medication was discontinued when FLACC scores remained ≤ 3 on two consecutive assessments; (2) Catheter management featuring early removal (urinary catheters within 24 hours, NGTs unless gastric output exceeded 50 mL/day of bilious content), with abdominal drains (when required) typically removed by length of stay (LOS) 2; (3) Progressive mobilization protocol initiating bedside activities at 6 hours, advancing to assisted ambulation (or caregiver-assisted movement for toddlers) by LOS 1[18]; and (4) Nutritional rehabilitation beginning with clear liquids on LOS 1, advancing to full feeds with concurrent IV fluid adjustment based on enteral intake. The TRAD group received conventional postoperative management consisting of: (1) On-demand oral acetaminophen or ibuprofen administration for FLACC scores ≥ 4; (2) Delayed catheter removal with urinary catheters maintained until LOS 2-3, NGTs until output became clear (typically LOS 3-4), and abdominal drains until daily output decreased below 20 mL; (3) Prescribed bed rest for 2-3 days; and (4) Graduated nutritional advancement was initiated with oral intake following the return of bowel function, while weight-based IV fluid supplementation was maintained throughout the transition.

A satisfaction survey assessing medical services was conducted among caregivers on the day of discharge. Satisfaction rate was calculated using the formula: [(number of satisfied cases + number of basically satisfied cases)/total number of cases] × 100%[19].

Discharge requirements: Patients were discharged upon meeting all of the following criteria: (1) Successful transition to full oral feeding without gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms; (2) Cessation of IV fluids and removal of all catheters; (3) Satisfactory wound healing with restored bowel and bladder function; (4) Absence of clinical symptoms with stable vital signs; and (5) Normalization of laboratory parameters (complete blood count, biochemistry) and abdominal ultrasound findings.

Follow-up protocol: A dedicated nurse specialist performed systematic telephone follow-up at 72 hours post-discharge, evaluating symptom progression, nutritional tolerance, and surgical site recovery. Caregivers received real-time clinical guidance for any warning signs (including fever, abdominal distension, or emesis), with prompt hospital readmission when indicated. All participants completed standardized postoperative evaluation at 30 ± 2 days following surgical intervention.

Clinical indicators: (1) Preoperative data: Demographic characteristics (age, sex, weight) and anesthesia records (American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, anesthesia technique); (2) Intraoperative data: Surgical parameters [procedure type (wedge/segmental resection), operative duration, blood loss], technical details (fluid administration rate, diverticulum location relative to ileocecal valve), and anesthesia recovery time; and (3) Postoperative recovery indicators: Drainage utilization metrics (placement rate and duration), early recovery measures (bowel function return, IV dependence duration), pain management outcomes (FLACC scores, analgesic requirements), LOS and caregiver satisfaction scores.

Laboratory parameters: Inflammatory markers [white blood cell, neutrophil (NEUT), C-reactive protein (CRP)] and metabolic indicators [hemoglobin, prealbumin (PAB), blood glucose] were measured preoperatively and on LOS 2 (40 hours after surgery) of in both cohorts.

Postoperative outcomes: (1) Complications included GI symptoms (nausea/vomiting, abdominal distension), respiratory complications, and surgical site infections (umbilical/intra-abdominal); and (2) The 30-day readmission rate was analyzed for cases of partial intestinal obstruction or residual intra-abdominal infection.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Normally distributed continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using independent t-tests. Non-normally distributed continuous data were expressed as median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) and analyzed via Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data was presented as n (%) and compared using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (where appropriate). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

The cohort comprised 78 pediatric patients undergoing laparoscopic-assisted MD resection (ERAS group = 40, TRAD group = 38). Both groups demonstrated comparable baseline demographics (gender, age, weight, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification) and laboratory parameters (inflammatory markers, nutritional indices), with no statistically significant differences (all P > 0.05). Notably, the ERAS group exhibited significantly elevated median blood glucose levels during anesthesia induction compared to the TRAD group (5.38 mmol/L vs 4.60 mmol/L, P < 0.001). Complete comparative data are presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | ERAS group (n = 40) | TRAD group (n = 38) | P value | Hedges (g) | Odds ratio | 95%CI |

| Gender | 0.406 | 0.66 | 0.25-1.75 | |||

| Male | 26 (65.00) | 28 (73.68) | ||||

| Female | 14 (35.00) | 10 (26.32) | ||||

| Age (months) | 60.00 (34.75, 90.00) | 84.00 (39.00, 91.75) | 0.331 | -0.22 | -19.68 to 6.40 | |

| Weight (kg) | 21.35 (15.75, 26.25) | 25.00 (15.75, 27.00) | 0.420 | -0.18 | -4.60 to 1.65 | |

| ASA physical status | 0.493 | 1.37 | 0.56-3.33 | |||

| Ⅱ | 21 (52.50) | 17 (44.74) | ||||

| Ⅲ | 19 (47.50) | 21 (55.26) | ||||

| Laboratory indicators | ||||||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 8.39 (6.71, 14.44) | 9.75 (5.89, 14.82) | 0.951 | -0.01 | -2.62 to 1.84 | |

| NEUT (× 109/L) | 4.58 (2.70, 11.91) | 6.60 (3.20, 12.50) | 0.460 | -0.17 | -0.17 to -3.16 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 4.50 (2.50, 19.20) | 6.50 (4.10, 21.50) | 0.265 | -0.71 | -21.22 to 10.49 | |

| Hb (g/L) | 123.53 ± 15.62 | 117.03 ± 15.16 | 0.068 | -0.44 | -0.39 to 13.38 | |

| PAB (g/L) | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.223 | -0.28 | -0.03 to 0.01 | |

| Glu (mmol/L) | 5.38 (5.01, 6.91) | 4.60 (4.09, 5.33) | < 0.001 | -1.02 | 0.64-1.67 |

Both groups successfully completed surgery with no mortality. While operative duration (P = 0.364), blood loss (P = 0.911), surgical approach (P = 0.632), and diverticulum location (P = 0.490) were comparable between groups, the ERAS group demonstrated significantly reduced intraoperative fluid administration (5.00 mL/kg/h vs 8.00 mL/kg/h, P < 0.001). The ERAS protocol significantly decreased postoperative catheter utilization: NGTs: 47.50% vs 78.95% (P = 0.004); Urinary catheters: 12.50% vs 31.58% (P = 0.041); Abdominal drains: 17.50% vs 44.74% (P = 0.009). Anesthesia management differed significantly, with combined general-caudal anesthesia more prevalent in ERAS cases (80.00% vs 23.68%, P < 0.001), though recovery times were equivalent (Table 2).

| Parameter | ERAS group (n = 40) | TRAD group (n = 38) | P value | Hedges (g) | Odds ratio | 95%CI |

| Operation time (minutes) | 92.20 ± 21.35 | 88.11 ± 17.99 | 0.364 | 0.20 | -4.83 to 13.02 | |

| Blood loss (mL) | 10.00 (5.00, 10.00) | 10.00 (5.00, 10.00) | 0.911 | -0.02 | -2.42 to 2.94 | |

| Surgical approach | 0.632 | 1.24 | 0.51, 3.04 | |||

| Wedge resection | 19 (47.50) | 16 (42.10) | ||||

| Segmental resection | 21 (52.50) | 22 (57.90) | ||||

| Diverticulum location (cm) | 44.50 ± 18.87 | 47.76 ± 22.57 | 0.490 | -0.16 | -12.63 to 6.10 | |

| Infusion speed (mL/kg/hour) | 5.00 (5.00, 6.00) | 8.00 (7.00, 8.75) | < 0.001 | -1.65 | -2.95 to -1.53 | |

| Combined anesthesia | 32 (80.00) | 9 (23.68) | < 0.001 | 12.89 | 4.39-37.83 | |

| Catheter utilization | ||||||

| NGTs | 19 (47.50) | 30 (78.95) | 0.004 | 0.24 | 0.09-0.65 | |

| Urinary catheters | 5 (12.50) | 12 (31.58) | 0.041 | 0.31 | 0.10-0.99 | |

| Abdominal drains | 7 (17.50) | 17 (44.74) | 0.009 | 0.26 | 0.09-0.74 |

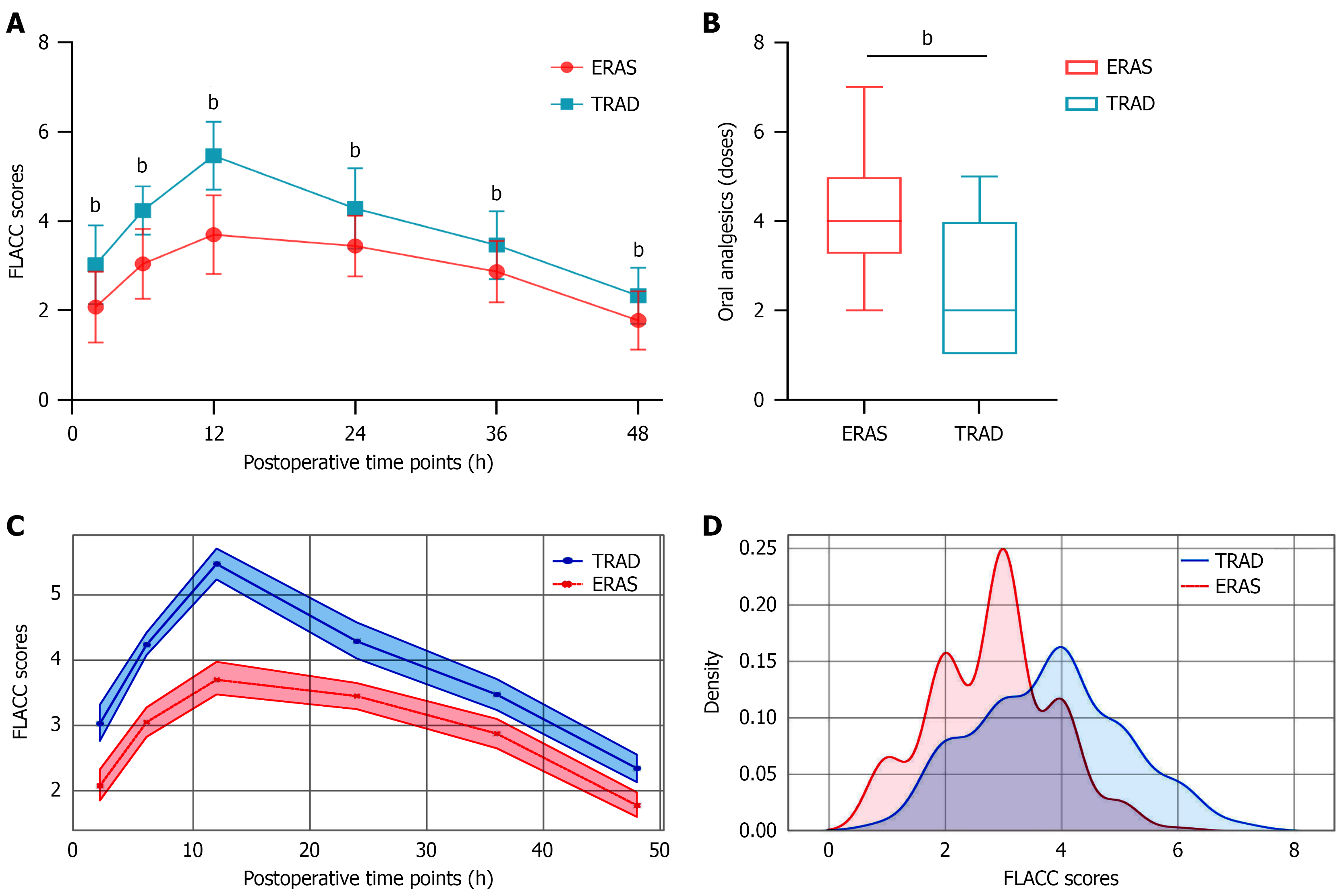

Pain management: The ERAS protocol demonstrated superior pain management, with significantly lower FLACC scores at all postoperative time points (2-48 hours; all P < 0.001; Figure 2A), despite requiring more frequent analgesic administration (4.00 doses vs 2.00 doses; P < 0.001; Figure 2B). A linear mixed-effects model was used to analyze the intra-individual correlation of pain (assessed via FLACC scores) among participants in different groups over the 2-48 hours postoperative period (Table 3). Combined with the main effect of grouping-where the ERAS group had lower baseline pain-these results suggest that the gap in pain scores between the two groups gradually narrowed over time: The ERAS group exhibited lower initial pain but slower pain relief, whereas the TRAD group showed higher initial pain but faster pain relief (Figure 2C and D).

| Variable | β (95%CI) | t value | P value |

| Group (ERAS vs TRAD) | -1.34 (-1.66 to -1.02) | -8.251 | < 0.001 |

| Time (continuous) | -0.03 (-0.04 to -0.02) | -7.075 | < 0.001 |

| Group time | 0.02 (0.01-0.03) | 2.751 | 0.006 |

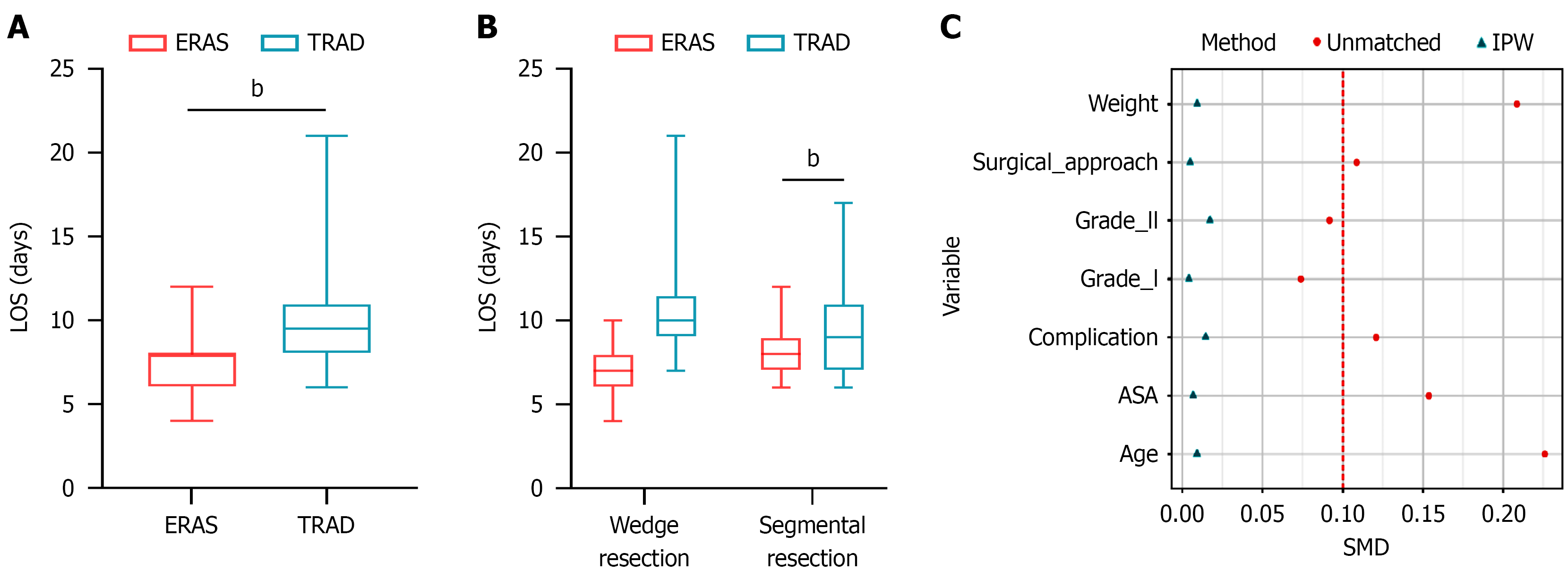

Postoperative LOS: The implementation of ERAS significantly reduced postoperative LOS (8.00 days vs 9.50 days; P < 0.001; Figure 3A). This reduction was most pronounced in patients undergoing segmental resection (6.98 days vs 10.00 days; P < 0.001), whereas patients undergoing wedge resection showed a non-significant trend toward shorter LOS (8.00 days vs 9.00 days; P = 0.354; Figure 3B). Complete data are available in Table 4. Figure 3C presents the standardized mean differences of various covariates before and after inverse probability weighting (IPW). This finding indicates that IPW effectively balanced the distribution of covariates between groups, a critical step for reducing confounding bias when analyzing the effect of ERAS implementation on LOS. Regardless of whether IPW was applied, the LOS in the ERAS group was significantly shorter than that in the TRAD group, with extremely strong statistical significance (both P < 0.001); details are provided in Table 5. This finding suggests that the degree of covariate confounding between the two groups in the original data was low. Moreover, the weighted results eliminated potential confounding effects and thus hold greater value for causal inference than the unweighted results.

| Parameter | ERAS group (n = 40) | TRAD group (n = 38) | P value | Hedges (g) | 95%CI |

| FLACC pain scores | |||||

| 2 hours | 2.00 (1.75, 3.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00) | < 0.001 | -1.09 | -1.32 to -0.58 |

| 6 hours | 3.00 (2.75, 4.00) | 4.00 (4.00, 4.00) | < 0.001 | -1.89 | -1.49 to -0.89 |

| 12 hours | 4.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 5.00 (5.00, 6.00) | < 0.001 | -2.22 | -2.14 to -1.41 |

| 24 hours | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | 4.00 (4.00, 5.00) | < 0.001 | -1.09 | -1.19 to -0.49 |

| 36 hours | 3.00 (2.75, 3.00) | 4.00 (3.00, 4.00) | < 0.001 | -0.83 | -0.92 to -0.28 |

| 48 hours | 2.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) | < 0.001 | -0.87 | -0.85 to -0.28 |

| Oral analgesics (administrations) | 4.00 (3.75, 5.00) | 2.00 (1.00, 3.75) | < 0.001 | -1.33 | 1.17-2.32 |

| Postoperative LOS | 8.00 (6.00, 8.00) | 9.50 (8.00, 11.00) | < 0.001 | -1.16 | -4.06 to -1.63 |

| Wedge resection | 8.00 (7.00, 9.00) | 9.00 (7.00, 11.00) | 0.354 | -0.31 | -2.77 to 0.31 |

| Segmental resection | 6.98 (6.00, 8.00) | 10.00 (9.00, 11.05) | < 0.001 | -2.10 | -5.88 to -2.39 |

Clinical outcomes: The ERAS protocol significantly accelerated GI recovery, with: Earlier mobilization (1.00 days vs 3.00 days), faster return of bowel function (2.00 days vs 3.00 days), shorter time to TEN (5.00 days vs 6.50 days), and reduced IV dependence (6.00 vs 8.00 days; all P < 0.001; Table 6). The ERAS protocol demonstrated significant reductions in postoperative catheter duration, with median retention times substantially shorter than conventional management: NGTs (2.00 days vs 3.00 days), urinary catheters (1.00 days vs 3.00 days), and abdominal drains (2.71 ± 0.76 days vs 4.72 ± 1.23 days; all P < 0.05). Complication rates were comparable between groups [ERAS: 17.50% (7/40) vs TRAD: 13.16% (5/38), P = 0.595]. All complications were Clavien-Dindo grade I-II and resolved with conservative management[20]. The implementation of the ERAS protocol was associated with higher parental satisfaction (92.50% vs 86.84%, P = 0.653) and a non-significant difference in 30-day readmission rates (1 case per group: Incomplete obstruction vs residual abdominal infection; both managed conservatively; Table 6).

| Parameter | ERAS group (n = 40) | TRAD group (n = 38) | P value | Hedges (g) | Odds ratio | 95%CI |

| Recovery parameters (days) | ||||||

| Time to ambulation | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | < 0.001 | -1.59 | -1.50 to -0.85 | |

| First flatus | 2.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.75) | < 0.001 | -1.12 | -1.30 to -0.58 | |

| TEN achievements | 5.00 (5.00, 6.00) | 6.50 (6.00, 8.00) | < 0.001 | -1.36 | -2.22 to -1.10 | |

| IV duration | 6.00 (5.00, 6.00) | 8.00 (7.00, 9.00) | < 0.001 | -1.92 | -3.09 to -1.68 | |

| Catheter duration (days) | ||||||

| NGTs | 2.00 (1.50, 3.00) | 3.00 (3.00, 4.00) | < 0.001 | -1.44 | -2.26 to -0.84 | |

| Urinary catheters | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 0.016 | -1.38 | -2.11 to -0.42 | |

| Abdominal drains | 2.71 ± 0.76 | 4.72 ± 1.23 | 0.001 | -1.73 | -3.04 to -0.97 | |

| Complications | 7 (17.50) | 5 (13.16) | 0.595 | 1.40 | 0.40-4.86 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3 (7.50) | 2 (5.26) | 1 | 1.46 | 0.23-9.26 | |

| Abdominal distension | 5 (12.50) | 4 (10.53) | 1 | 1.21 | 0.30-4.91 | |

| Cough/sputum production | 2 (5.00) | 2 (5.26) | 1 | 0.95 | 0.13-7.09 | |

| Umbilical infection | 1 (2.50) | 0 (0.00) | 1 | 2.92 | 0.12-74.02 | |

| Residual abdominal infection | 1 (2.50) | 1 (2.63) | 1 | 0.97 | 0.06-16.15 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.63) | 0.487 | 0.31 | 0.01-7.81 | |

| Clavien-Dindo classification | 1 | 0.89 | 0.09-9.16 | |||

| Grade I | 4 (10.00) | 3 (7.90) | ||||

| Grade II | 3 (7.50) | 2 (5.26) | ||||

| Parental satisfaction | 37 (92.50) | 33 (86.84) | 0.476 | 1.87 | 0.41-8.43 | |

| 30-day readmission | 1 (2.50) | 1 (2.63) | 1 | 0.95 | 0.06-15.73 | |

| Incomplete obstruction | 1 (2.50) | 0 (0.00) | 1 | 2.92 | 0.12-74.02 | |

| Residual abdominal infection | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.63) | 0.487 | 0.31 | 0.01-7.81 | |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 9.66 ± 3.02 | 10.62 ± 4.01 | 0.336 | -0.26 | -2.93 to 1.02 | |

| NEUT (× 109/L) | 5.98 ± 2.02 | 8.01 ± 3.98 | 0.015 | -0.60 | -3.63 to -0.41 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 13.67 (7.85, 22.11) | 19.63 (7.10, 32.69) | 0.20 | -0.35 | -21.83 to 0.05 | |

| Hb (g/L) | 117.82 ± 13.51 | 114.46 ± 12.60 | 0.348 | 0.26 | -3.75 to 10.46 | |

| PAB (g/L) | 0.18 (0.15, 0.21) | 0.15 (0.13, 0.18) | 0.01 | -0.60 | 0.01-0.04 | |

| Glu (mmol/L) | 5.53 (4.79, 6.43) | 6.46 (5.35, 8.81) | 0.023 | -0.60 | -2.25 to -0.03 |

Laboratory parameters: LOS 2 analysis showed comparable white blood cell (P = 0.336) and hemoglobin (P = 0.348) between groups. The ERAS group demonstrated superior metabolic/inflammatory profiles with: Lower median blood glucose (5.53 mmol/L vs 6.46 mmol/L), reduced NEUT [(5.98 ± 2.02) × 109/L vs (8.01 ± 3.98) × 109/L], decreased median CRP (13.67 mg/L vs 19.63 mg/L), and higher PAB (0.18 g/L vs 0.15 g/L; Table 6).

Surgical resection remains the gold standard for MD, with lesions typically found within 100 cm of the ileocecal valve[21]. While laparoscopic approaches have enhanced surgical outcomes[22], pediatric care still faces challenges such as postoperative morbidity and prolonged hospitalization. Although ERAS protocols are widely adopted in adults[23], their pediatric application has lagged[24], necessitating age-specific modifications[25]. Our study demonstrates that a tailored ERAS protocol safely optimizes recovery in pediatric laparoscopic MD resection. The ERAS group achieved significantly reduced LOS without elevating complication or readmission rates. These findings validate ERAS feasibility in pediatric intestinal surgery, highlighting its dual benefit of accelerating recovery while upholding safety.

MD in children is invariably diagnosed following symptomatic presentation, as most caregivers lack prior awareness of this congenital anomaly. This clinical reality necessitates specialized preoperative education programs to ensure successful ERAS protocol execution. Our modified approach incorporated three key elements: (1) Developmentally-appropriate caregiver counseling to establish accurate treatment expectations and improve postoperative adherence; (2) Implementation of play-based preparatory interventions to overcome communication barriers and alleviate preoperative anxiety in young children; and (3) Evidence-based fasting modifications permitting clear fluids until 2 hours preoperatively, including 10% glucose solution administration to maintain metabolic stability while minimizing distress[26]. A critical procedural adaptation involved deferring NGT and urinary catheter placement until after anesthesia induction, contrasting with the traditional practice of awake insertion. This child-centric modification yielded measurable improve

The ERAS protocol incorporated several evidence-based intraoperative modifications that optimized postoperative recovery. First, a restrictive fluid regimen was implemented, which has been shown to reduce pulmonary complications, minimize cardiac strain and intestinal edema, and potentially shorten hospital stays[28]. Second, active temperature maintenance (core temperature ≥ 36 °C) through rigorous thermal management significantly decreased hypothermia-associated adverse effects including shivering, surgical site infections, and coagulopathy compared to conventional practices[29].

We implemented an evidence-based, three-component analgesic strategy consisting of: (1) Preemptive local anesthetic infiltration with 0.5% ropivacaine; (2) Scheduled administration of oral acetaminophen/ibuprofen, and (3) Developmentally-appropriate non-pharmacologic interventions. This comprehensive approach, grounded in established evidence[30], achieved superior pain control compared to conventional management, as objectively demonstrated by FLACC scale assessments showing consistent superiority across all postoperative evaluation time points (all P < 0.001). The clinical benefits of this protocol were multifold: (1) Superior pain control enabled earlier patient mobilization; (2) Reduced opioid exposure minimized GI motility impairment; (3) Early ambulation stimulated vagal tone, accelerating ileus resolution[31]; and (4) Standardized protocol ensured consistent pain management quality. The observed difference in FLACC scores reflects this fundamental design distinction and should not be interpreted as a direct comparison of analgesic efficacy.

Traditional protocols mandated NGT retention until full GI recovery (evidenced by flatus/bowel movements and no nausea/vomiting). However, modern ERAS guidelines for abdominal surgery oppose routine NGT use, reserving them only for confirmed gastroparesis[32]. Growing evidence shows early NGT removal accelerates GI recovery without increasing aspiration risk[33]. Our pediatric ERAS protocol adopted 24-hour postoperative NGT removal, facilitating early mobilization (both active and passive) and enhancing recovery. This approach safely extends adult ERAS principles while addressing pediatric-specific needs.

Early enteral nutrition helps attenuate postoperative hypermetabolism, stabilize stress-induced glucose fluctuations, and enhance protein synthesis[34]. Our pediatric ERAS protocol initiated enteral nutrition on LOS 1 with 20% glucose solution via tongue-tip dripping, gradually advancing to water and a low-residue liquid diet. This approach was well tolerated, with no increase in abdominal distension or vomiting. The ERAS group exhibited faster bowel recovery, evidenced by earlier first flatus and shorter time to TEN. These metabolic advantages reduced IV fluid needs and lowered hospitalization costs. Additionally, this minimal-drainage, early-feeding strategy improved family compliance through better understanding and trust, leading to higher caregiver satisfaction.

Our study revealed superior metabolic and inflammatory profiles in ERAS patients, characterized by lower LOS 2 blood glucose levels and higher PAB concentrations, reflecting improved anabolic response and insulin sensitivity with early nutrition[34]. These findings carry clinical importance as postoperative hyperglycemia correlates with higher infection rates, impaired wound healing, and potential organ dysfunction[35].

Inflammatory marker analysis revealed significant findings. Surgical trauma typically induces NEUT activation, triggering an inflammatory cascade via chemokine-mediated recruitment[36]. Simultaneously, CRP - a hepatocyte-derived acute-phase reactant - quantitatively reflected systemic inflammation and surgical stress[37,38]. The ERAS group demonstrated significantly lower NEUT counts and CRP levels, indicating the protocol's effectiveness in mitigating postoperative inflammatory responses and surgical stress.

Our study evaluated ERAS efficacy in pediatric laparoscopic-assisted MD resection. Like prior reports[39], we found strict protocol adherence crucial for optimal outcomes. ERAS benefits were more pronounced in segmental resections than wedge resections, particularly regarding LOS. While wedge resection showed a non-significant trend toward shorter LOS (P = 0.354), this may reflect smaller subgroup sizes, milder inflammation, or reduced surgical trauma. These findings suggest a potential dose-response relationship between surgical extent and ERAS benefits, with more extensive procedures potentially gaining greater advantage. However, this hypothesis requires validation through larger prospective studies.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective, non-randomized design may introduce bias compared to prospective trials. Second, the single-center setting and modest sample size affect generalizability. Finally, pediatric variability necessitates protocol adjustments (e.g., prolonged NGT for significant bilious drainage), requiring age-specific optimization. Despite these constraints, our results demonstrate ERAS safety and feasibility for pediatric laparoscopic MD resection. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger cohorts should validate these findings and establish age-adapted protocols for optimal implementation.

| 1. | Redman EP, Mishra PR, Stringer MD. Laparoscopic diverticulectomy or laparoscopic-assisted resection of symptomatic Meckel diverticulum in children? A systematic review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:869-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Butler K, Peachey T, Sidhu R, Tai FWD. Demystifying Meckel's diverticulum - a guide for the gastroenterologist. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2025;41:146-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li B, Gao J, Ding X, Li X, Yu Y, Long Y, Wang X, Wu X, Gao Y. Diagnostic accuracy of [(99m) Tc]pertechnetate scintigraphy in pediatric patients with suspected Meckel's diverticulum: a 12-year, monocentric, retrospective experience. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1585313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Skertich NJ, Ingram MC, Grunvald MW, Williams MD, Ritz E, Shah AN, Raval MV. Outcomes of Laparoscopic Versus Open Resection of Meckel's Diverticulum. J Surg Res. 2021;264:362-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lobo DN, Joshi GP, Kehlet H. Challenges in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) research. Br J Anaesth. 2024;133:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tian Q, Wang H, Guo T, Yao B, Liu Y, Zhu B. The efficacy and safety of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) Program in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2024;56:2306194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Remulla D, Bradley JF 3rd, Henderson W, Lewis RC, Kreuz B, Beffa LR; Abdominal Core Health Quality Collaborative Quality Improvement Committee. Consensus in ERAS protocols for ventral hernia repair: evidence-based recommendations from the ACHQC QI Committee. Hernia. 2024;29:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elferink SEM, Bretveld R, Kwast ABG, Asselman M, Essink JGJ, Potters JW, van der Palen J. The effect of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) in renal surgery. World J Urol. 2024;42:490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aref H, Yunus T, Farghaly M, ElDahshan Y, Khan HJ, Alsaadi D, Jacobo FAA, Ahmed A, Mohamed A, Saber AY, Ali K, Alefranji F, Miranda E, Dakkak O. Comparative outcomes of ERAS and conventional methods in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a 5-Year prospective cohort study in Saudi Arabia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patel HN, Martin B, Pisavadia B, Soccorso G, Jester I, Pachl M, Singh M, Lander A, Arul GS. An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for laparoscopic gastrostomy insertion facilitates 23-h discharge. Pediatr Surg Int. 2025;41:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mansfield SA, Kotagal M, Hartman SJ, Murphy AJ, Davidoff AM, Hogan B, Ha D, Anghelescu DL, Mecoli M, Cost NG, Rove KO. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for Pediatric Abdominal Tumor Resections: A Prospective Multi-institution Study. J Pediatr Surg. 2025;60:162046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tang J, Liu X, Ma T, Lv X, Jiang W, Zhang J, Lu C, Chen H, Li W, Li H, Xie H, Du C, Geng Q, Feng J, Tang W. Application of enhanced recovery after surgery during the perioperative period in infants with Hirschsprung's disease - A multi-center randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:2062-2069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 13. | Pilkington M, Nelson G, Pentz B, Marchand T, Lloyd E, Chiu PPL, de Beer D, de Silva N, Else S, Fecteau A, Giuliani S, Hannam S, Howlett A, Lee KS, Levin D, O'Rourke L, Stephen L, Wilson L, Brindle ME. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations for Neonatal Perioperative Care. JAMA Surg. 2024;159:1071-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Kifle F, Belay E, Kifleyohanes T, Demissie B, Galcha D, Mulye B, Presser E, Oodit R, Maswime S, Biccard B. Adherence to Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) With Bellwether Surgical Procedures in Ethiopia: A Retrospective Study. World J Surg. 2025;49:1040-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lasala J, Mena GE, Iniesta MD, Cata J, Pitcher B, Wendell W, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Cain K, Basabe M, Suki T, Meyer LA, Ramirez PT. Impact of anesthesia technique on post-operative opioid use in open gynecologic surgery in an enhanced recovery after surgery pathway. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ahmed M, Saeed R, Allawi A, Zajicek J. Meckel's Diverticulum With Perforation. Cureus. 2024;16:e67026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gustafsson UO, Rockall TA, Wexner S, How KY, Emile S, Marchuk A, Fawcett WJ, Sioson M, Riedel B, Chahal R, Balfour A, Baldini G, de Groof EJ, Romagnoli S, Coca-Martinez M, Grass F, Brindle M, Hubner M. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations 2025. Surgery. 2025;184:109397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang C, Wang Y, Zhao P, Li T, Li F, Li Z, Qi Y, Wang X, Shi W, Liu L, Li G, Wang Y. Application of enhanced recovery after surgery during the perioperative period in children with Meckel's diverticulum-a single-center prospective clinical trial. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1378786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Reismann M, Dingemann J, Wolters M, Laupichler B, Suempelmann R, Ure BM. Fast-track concepts in routine pediatric surgery: a prospective study in 436 infants and children. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huepenbecker SP, Soliman PT, Meyer LA, Iniesta MD, Chisholm GB, Taylor JS, Wilke RN, Fleming ND. Perioperative outcomes in gynecologic pelvic exenteration before and after implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery program. Gynecol Oncol. 2024;189:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tang R, Zhang P, Qi SQ, Zhou CX. Giant Meckel Diverticulum Causing Pediatric Intestinal Obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;120:1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang X, Liu C, Sun S, Dong C, Zhao S, Bokhary ZM, Liu N, Wu J, Ding G, Zhang S, Geng L, Liu H, Fu T, Gao X, Niu Q. Clinical features and treatment of heterotopic pancreas in children: a multi-center retrospective study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024;40:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang SK, Wang QJ, Wang P, Li XY, Cui P, Wang DF, Chen XL, Kong C, Lu SB. The impact of frailty on clinical outcomes of older patients undergoing enhanced recovery after lumbar fusion surgery: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2024;110:4785-4795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yan H, Yan M, Xiong Y, Li Y, Wang H, Jia Y, Yuan S. Efficacy of perioperative pain management in paediatric cardiac surgery: a protocol for a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e084547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xie N, Xie H, Li W, Zhu Z, Wang X, Tang W. So many measures in ERAS protocol: Which matters most? Nutrition. 2024;122:112384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fall F, Pace D, Brothers J, Jaszczyszyn D, Gong J, Purohit M, Sadacharam K, Lang RS, Berman L, Lin C, Reichard K. Utilization of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol in pediatric laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a quality improvement project. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024;40:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mahesri K, Mayon L, Chiang YJ, Swartz MC, Moody K, Kapoor R, Austin M. An Enhanced Recovery Program for Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Surgical Oncology Patients Improves Outcomes After Surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2025;60:161912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Marques M, Tezier M, Tourret M, Cazenave L, Brun C, Duong LN, Cambon S, Pouliquen C, Ettori F, Sannini A, Gonzalez F, Bisbal M, Chow-Chine L, Servan L, de Guibert JM, Faucher M, Mokart D. Risk factors for postoperative acute kidney injury after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in the era of ERAS protocols: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0309549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang Y, Zhou D, Xiong W, Ge S. Modified protocol for Enhanced Recovery After Surgery is beneficial for achalasia patients undergoing peroral endoscopic myotomy: a randomized prospective trial. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2021;16:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Roy N, Parra MF, Brown ML, Sleeper LA, Kossowsky J, Baumer AM, Blitz SE, Booth JM, Higgins CE, Nasr VG, Del Nido PJ, Brusseau R. Erector spinae plane blocks for opioid-sparing multimodal pain management after pediatric cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;168:1742-1750.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang B, Han D, Hu X, Chen J, Liu Y, Wu J. Perioperative liberal drinking management promotes postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery after gynecological laparoscopic surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2024;97:111539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schäfer M, Mariette C, Braga M, Carli F, Demartines N, Griffin SM, Lassen K; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Group. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Takeda Y, Mise Y, Kishi Y, Sugo H, Kyoden Y, Hasegawa K, Takahashi Y, Saiura A. Enteral versus parental nutrition after pancreaticoduodenectomy under enhanced recovery after surgery protocol: study protocol for a multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial (ENE-PAN trial). Trials. 2022;23:917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Han L, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Chen H, Li W, Zhang M, Zhou J, Zhang L, Dou X, Wang X. Nutritional status of early oral feeding for gastric cancer patients after laparoscopic total gastrectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2025;51:109379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ceresoli M, Biloslavo A, Bisagni P, Ciuffa C, Fortuna L, La Greca A, Tartaglia D, Zago M, Ficari F, Foti G, Braga M; ERAS-emergency surgery collaborative group. Implementing Enhanced Perioperative Care in Emergency General Surgery: A Prospective Multicenter Observational Study. World J Surg. 2023;47:1339-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Salamanna F, Tedesco G, Sartori M, Contartese D, Asunis E, Cini C, Veronesi F, Martikos K, Fini M, Giavaresi G, Gasbarrini A. Clinical Outcomes and Inflammatory Response to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocol in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Surgery: An Observational Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:3723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gonvers S, Jurt J, Joliat GR, Halkic N, Melloul E, Hübner M, Demartines N, Labgaa I. Biological impact of an enhanced recovery after surgery programme in liver surgery. BJS Open. 2021;5:zraa015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ghiasi Hafezi S, Kolahi Ahari R, Saberi-Karimian M, Eslami Giski Z, Mansoori A, Ferns GA, Ebrahimi M, Heidari-Bakavoli A, Moohebati M, Yousefian S, Farrokhzadeh F, Esmaily H, Ghayour-Mobarhan M. Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and hematologic-inflammatory indices with risk of cardiovascular diseases: a population-based study with partial least squares structural equation modeling approach. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025;480:1909-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Antoniv M, Maldonado LJ, Nikiforchin A, Gershanik EF, Bleday R. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Compliance and Early Outcomes for Elective Colorectal Procedures by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. Ann Surg. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/