Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112175

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: October 13, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 0.6 Hours

Unplanned extubation (UE) after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography plus endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) increases patient morbidity and prolongs hospitalization duration.

To construct a risk prediction model for UE in patients undergoing ENBD to provide evidence for clinical nursing.

A multicenter retrospective study was conducted, collecting data from 981 patients undergoing ENBD from three hospitals in Chongqing from January 2018 to June 2024, randomly allocated to modeling and validation groups in a 7:3 ratio. Logistic regression analysis was used to screen independent risk factors, construct prediction models, and draw nomograms.

The overall incidence of UE was 6.12% (60/981). The majority (70.00%) of extubations occurred within 24-72 h postoperatively. Multivariate logistic regre

The six-factor risk prediction model had good discrimination and accuracy, which can provide clinical nursing staff with scientific evidence to identify patients at high risk and help reduce the incidence of UE.

Core Tip: This multicenter retrospective study developed and validated a six-factor risk prediction model for unplanned nasobiliary tube extubation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography plus endoscopic nasobiliary drainage. Independent predictors included age ≥ 61 years, smoking history, prolonged fasting, catheter duration, consciousness change, and low serum albumin. The nomogram demonstrated excellent discrimination (area under the curve = 0.881) and clinical utility. A total score ≥ 199 indicated high risk. This tool enables early identification of patients at high risk and supports targeted nursing interventions to reduce complications, hospitalization time, and healthcare costs.

- Citation: Li WJ, Mi N, Huang X, Liu CS, Zhang ST, Liao Y, Yu Y. Predicting unplanned extubation risk in patients with endoscopic nasobiliary drainage. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 112175

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/112175.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.112175

In China biliary pathologies demonstrate significant clinical prevalence with choledocholithiasis affecting 4%-7% of the population, primary sclerosing cholangitis occurring in approximately 0.77-0.94 per 100000 individuals, and various biliary neoplasms comprising 2%-3% of gastrointestinal malignancies. Bile duct carcinomas represent the most devastating of these conditions and are characterized by a dismal 5-year survival rate of merely 10%-20%.

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD), established as a therapeutic modality since the 1970s, has emerged as a preferred minimally invasive approach for managing biliary obstructions, offering superior outcomes through reduced surgical trauma, accelerated recovery periods, and diminished complication rates compared with traditional open procedures[1]. Nevertheless, inadvertent nasobiliary tube dislodgement constitutes a prevalent complication, occurring in 8%-25% of recipients of ENBD and presenting substantial nursing management challenges. This adverse event not only disrupts therapeutic bile drainage but also precipitates patient distress manifested as pain, pyrexia, and jaundice while potentially triggering severe sequelae including acute cholangitis or pancreatitis, resulting in prolonged hospitalization (3-7 additional days), escalated healthcare expenditures (20%-40% increase), and compromised patient satisfaction[2].

Contemporary preventive approaches predominantly rely on empirical nursing judgment and standardized interventions such as continuous monitoring, patient education, and physical restraint application, all of which lack individualized, evidence-based foundations and yield suboptimal outcomes across diverse patient risk profiles. While predictive modeling has demonstrated success in various nursing specialties including pressure ulcer prevention, fall risk assessment, and infection control, specialized predictive tools for ENBD-related unplanned extubation (UE) remain scarce with existing literature predominantly comprising small-scale, single-center investigations[3,4].

However, UE of nasobiliary tubes occurs in 8%-25% of patients who underwent ENBD across different medical centers, representing a major nursing challenge that not only interrupts bile drainage and causes immediate patient discomfort including pain, fever, and jaundice but may also trigger serious complications such as acute cholangitis, pancreatitis, or biliary sepsis. The consequences of UE are multifaceted and severe: Patients experience immediate loss of biliary decompression leading to recurrent symptoms, increased risk of ascending infection due to bile stasis, potential need for repeat procedures with associated risks, and significant psychological distress from treatment failure. These events result in extended hospital stays of 3-7 days on average, increased healthcare costs of 20%-40% due to additional procedures and prolonged monitoring, reduced patient satisfaction scores, and increased nursing workload and stress. Furthermore, UE may compromise the success of subsequent interventions and delay definitive treatment, particularly problematic in patients with malignant obstructions in which timing is critical for optimal outcomes.

Therefore, this study aimed to construct and validate a comprehensive, culturally appropriate risk prediction model for UE in patients who underwent ENBD through large-sample, multifactor analysis incorporating patient demographics, clinical characteristics, psychosocial variables, procedural factors, and environmental considerations[5-11]. By employing advanced statistical methodologies including machine learning algorithms and external validation approaches, we sought to provide evidence-based decision-making tools for clinical nursing practice that can accurately identify patients at high risk, guide targeted prevention interventions, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately improve patient safety, reduce healthcare costs, and enhance quality of care in biliary disease management.

This study was a multicenter, retrospective study using convenience sampling to select patients who underwent ENBD in the hepatobiliary surgery departments of three tertiary hospitals in Chongqing from January 2018 to June 2024.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients with typical clinical characteristics of biliary system diseases such as abdominal pain, jaundice, vomiting, diagnosed by imaging (magnetic resonance imaging) examination and underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) + ENBD surgery; (2) Age 18-65 years; (3) Hospitalized patients with nasobiliary tubes retained after ERCP; (4) Informed consent for drainage surgery and intervention; and (5) Able to closely cooperate with treatment and assessment postoperatively.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Pregnant and lactating women, patients with mental disorders; (2) Surgical failure or inability to communicate normally; (3) Preoperative abdominal pain, cholangitis, pancreatitis, elevated body temperature, WBC count, and elevated amylase; and (4) Patients with obvious coagulation dysfunction, hepatic decompensation, combined cardiovascular and renal diseases, intestinal stenosis or obstruction, and moderate or above esophagogastric varices.

Patients were divided into the normal extubation (NE) group and UE group based on whether UE occurred during hospitalization. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University (Approval No. 2024-Research-135-02). According to logistic regression analysis sample size calculation requirements, each predictor required at least 5-10 patients who experienced UE. Through a literature review the study expected no more than 10 predictors to be included in the logistic regression model. Combined with previous research results, the incidence of nasobiliary tube UE was 9.11%. To ensure sufficient sample size for patients in the NE group and considering 10% sample loss, the required sample size was (10 × 5 ÷ 0.0911) ÷ 0.9 ≈ 610 cases, ultimately including 981 cases.

Presurgical preparation involved comprehensive ERCP + ENBD nasobiliary tube nursing education for all patients and family members. This education covered surgical procedure specifics, physician cooperation requirements, potential adverse reactions with management strategies, safety precautions, and essential psychological support. Post-surgical care protocols required daily tube assessments by nursing staff, who then provided tailored patient and family guidance based on evaluation findings: (1) Immediate post-surgical education. Nursing personnel promptly delivered drainage tube knowledge to patients and caregivers, encouraging frequent patient movement and positioning changes while cautioning against excessive motion that might cause tube displacement through traction forces; (2) Proper drainage device securing. Multiple nasobiliary tube wrappings with fixation at cheek and nasal wing locations, bedside drainage bag and equipment installation, and real-time drainage volume, quality observation, and documentation to maintain drainage effectiveness while preventing retrograde infections; (3) Drainage monitoring protocols. Sudden drainage volume reductions triggered immediate tube blockage assessments and low-pressure saline irrigation procedures. Increased drainage volumes with lighter coloration containing food particles indicated potential nasobiliary tube head displacement from bile duct to duodenum, resulting in compromised drainage capacity; and (4) Infection management. Active collaboration with prescribed anti-infection treatment protocols when infections developed.

Literature review and expert consultation guided comprehensive consideration of potential nasobiliary tube UE influencing factors, resulting in risk factor questionnaire development: (1) Demographics and general information. Gender, age, diagnostic procedures, surgical dates and duration, fasting periods, marital status, occupation, residence, number of children, smoking and drinking histories, medical histories, educational attainment, insurance coverage types, blood pressure, weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) measurements; (2) Disease-specific data. Nasobiliary tube retention duration, pain levels, cough presence, self-care capabilities, post-surgical pain, bile drainage volumes, post-surgical consciousness levels, restraint utilization, fever occurrence, and nausea and vomiting episodes; and (3) Laboratory parameters. Creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, fasting glucose levels, blood amylase, bilirubin reduction rates, WBC counts, neutrophil percentages, lymphocyte percentages, eosinophil percentages, basophil percentages, hemoglobin, red blood cell counts, and platelet counts. Data collection and extraction from hospital HIS information systems and nursing documentation were performed by Liao Y. Standardized questionnaires and judgment criteria facilitated risk factor collection by research personnel. Zhang ST conducted data accuracy verification and score recalculation, utilizing Excel software for data entry procedures.

SPSS 26.0 software facilitated all statistical analyses. Categorical variables received frequency and percentage expression with χ2 testing for group comparisons. Normally distributed continuous variables utilized mean ± SD while non-normally distributed continuous variables employed median and quartile presentation with rank-sum testing for comparisons. Binary logistic regression analysis incorporating stepwise forward Wald methodology screened independent risk factors and constructed predictive risk models. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve generation enabled model Youden index, critical value, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy analyses. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Model performance evaluation: ROC curves were used to analyze model discrimination and calculate area under the curve, Youden index, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy while model calibration was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, calibration curves (dividing patients into deciles based on predicted risk to compare observed vs expected event rates), and multiple calibration metrics including calibration intercept (α), calibration slope (β), Integrated Calibration Index, maximum calibration error (E_max), and Brier score with ideal calibration indicated by α = 0, β = 1 and lower Brier scores.

Bootstrap validation: Internal validation was performed using 1000 bootstrap samples (seed number: 12345), repeating the model development process including variable selection and coefficient estimation, calculating optimism-corrected C-index with bias-corrected confidence intervals obtained using the percentile method while assessing model stability by examining variable selection frequency across bootstrap samples.

Clinical utility assessment: Decision curve analysis was employed to evaluate the net benefit of the prediction model across different threshold probabilities compared with treat-all and treat-none strategies, providing practical guidance for clinical decision.

Group analysis showed that among 60 patients in the UE group, 39 were male (65.00%) and 21 were female (35.00%) with a mean age of 58.4 ± 10.2 years and 32 patients ≥ 61 years (53.33%) comprising the main proportion. Among 921 patients in the NE group, 503 were male (54.62%) and 418 female (45.38%) with a mean age of 52.3 ± 12.6 years and 502 patients aged 41-60 years (54.51%) as the main constituent. Regarding weight and BMI, the UE group had a mean weight of 62.8 ± 10.4 kg and a mean BMI of 22.9 ± 2.8 kg/m2 with a higher proportion of patients with obesity (16.67%). The NE group had a mean weight of 65.4 ± 11.9 kg and a mean BMI of 23.8 ± 3.3 kg/m2 with patients with normal weight comprising the majority (58.31%). Education level analysis showed the UE group was mainly junior high school and below (71.67%) with college and above education comprising only 6.67%. The NE group had relatively even education distribution with college and above education comprising 19.11%. The UE group had a significantly higher proportion of farmers (46.67%) while the NE group had a more diverse occupational distribution. Time distribution analysis found that 70.00% of UEs occurred within 24-72 h postoperatively with the second postoperative day being the peak period (35.00%), indicating the importance of early identification and focused monitoring. Detailed patient baseline characteristics were shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Unplanned extubation group (n = 60) | Normal extubation group (n = 921) | P value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 39 (65.00) | 503 (54.62) | 0.143 |

| Female | 21 (35.00) | 418 (45.38) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean age, years | 58.4 ± 10.2 | 52.3 ± 12.6 | < 0.001 |

| Age groups, years | |||

| ≤ 40 | 8 (13.33) | 201 (21.83) | < 0.01 |

| 41-60 | 20 (33.33) | 502 (54.51) | |

| ≥ 61 | 32 (53.33) | 218 (23.67) | |

| Anthropometric measurements | |||

| Weight, kg | 62.8 ± 10.4 | 65.4 ± 11.9 | 0.087 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9 ± 2.8 | 23.8 ± 3.3 | 0.054 |

| BMI categories | |||

| Underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2) | 3 (5.00) | 28 (3.04) | < 0.05 |

| Normal (18.5-23.9 kg/m2) | 37 (61.67) | 537 (58.31) | |

| Overweight (24.0-27.9 kg/m2) | 10 (16.67) | 284 (30.84) | |

| Obese (≥ 28.0 kg/m2) | 10 (16.67) | 72 (7.82) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary school or below | 25 (41.67) | 248 (26.93) | < 0.001 |

| Junior high school | 18 (30.00) | 277 (30.08) | |

| Senior high school/vocational | 13 (21.67) | 220 (23.89) | |

| College or above | 4 (6.67) | 176 (19.11) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Farmer | 28 (46.67) | 267 (29.00) | < 0.01 |

| Worker | 12 (20.00) | 201 (21.83) | |

| Office worker | 8 (13.33) | 185 (20.09) | |

| Retired | 10 (16.67) | 183 (19.87) | |

| Others | 2 (3.33) | 85 (9.23) | |

| Time distribution of UE | |||

| < 24 h | 12 (20.00) | ||

| 24 h ≤ Time < 48 h | 21 (35.00) | ||

| 48 h ≤ Time < 72 h | 21 (35.00) | ||

| ≥ 72 h | 6 (10.00) |

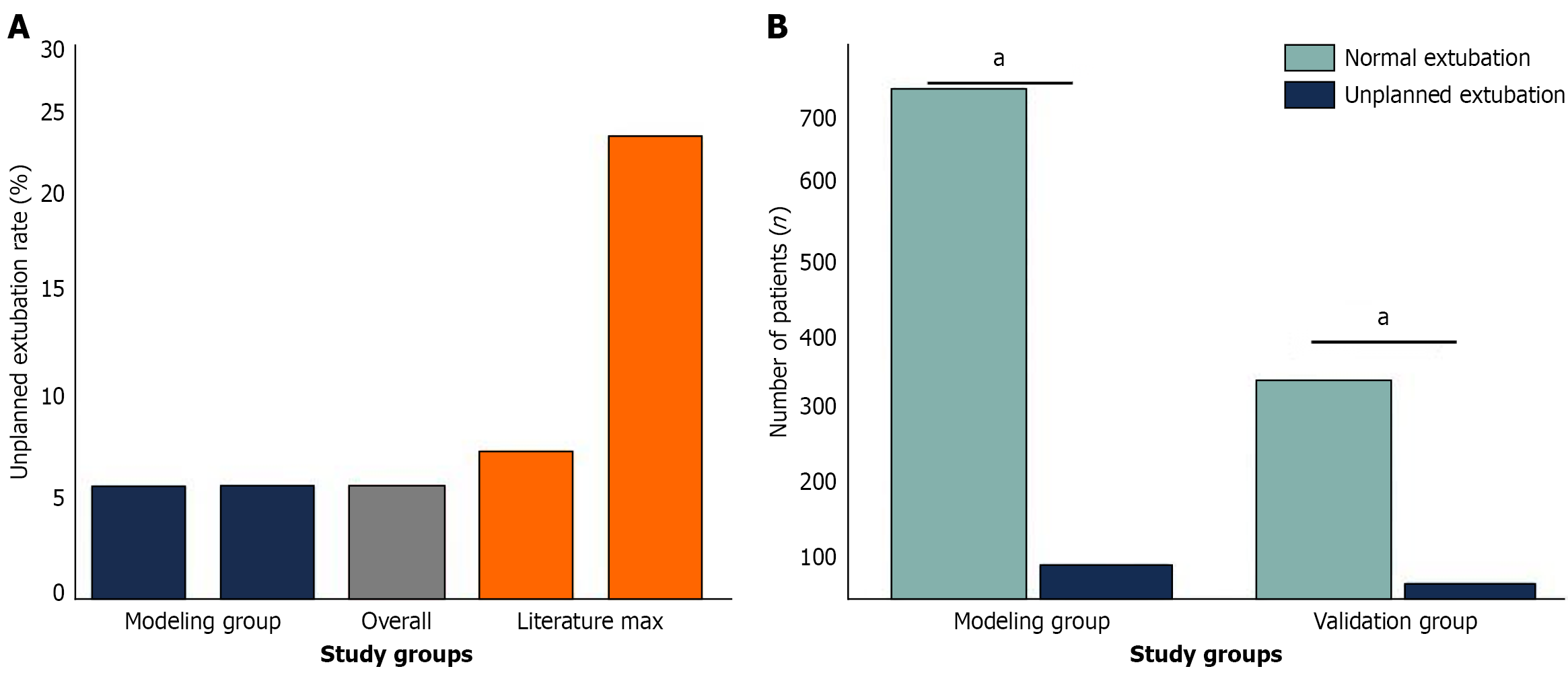

Cohort selection: This study was designed as a multicenter retrospective study, and patients were selected from the hepatobiliary surgery departments of three tertiary hospitals in Chongqing from January 2018 to June 2024, finally involving 981 eligible patients. All patients were randomly divided into modeling and validation groups at a ratio of 7:3 with random number table method for statistical demands and model building purposes (Figure 1). The modeling set contained a total of 687 patients with 645 successful extubation cases and 42 UPWs (6.11%, 42/687). The validation cohort consisted of 294 patients, including 276 successful extubation cases and 18 UE cases, and the incidence of UE was 6.12% (18/294). There was no significant between-group difference regarding the incidence of UE (P > 0.05), suggesting the rationality of grouping. Among the 981 patients 60 UE cases were reported, and a total of 6.12% (60/981) cases were UE. This incidence was lower than the 8%-25% range in domestic and international reports, indicating that the postoperative ENBD treatment in the hospitals investigated in this study was relatively uniform, and the nursing level was high (Figure 1).

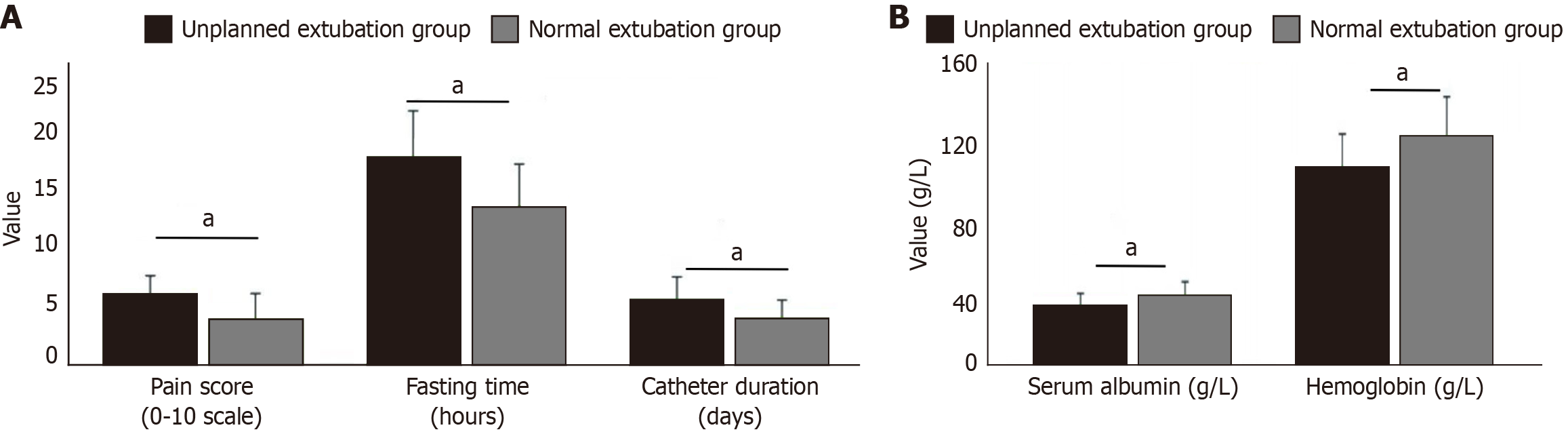

The univariate analysis indicated that there were significant differences of various variables in the UE group and the NE group (Figure 2). The education level was mainly junior high school and below (71.67% vs 56.31%, P < 0.001), which may have contributed to the compliance of patients who removed the endotracheal tube. Clinical symptom and behavioral type analysis revealed that patients in the UE group had a greater degree of pain (6.2 ± 1.8 vs 4.1 ± 2.3, P < 0.001), a significantly higher rate of smoking (58.33% vs 32.14%, P < 0.001), and a longer period of fasting (18.6 ± 4.2 h vs 14.2 ± 3.8 h, P < 0.001), which can make a patient irritable and unwell, subsequently affecting the safety of the tube. Lab results indicated that the UE group had more severe abnormal liver function indexes as well as lower serum albumin (32.4 ± 6.8 g/L vs 38.2 ± 7.4 g/L, P < 0.001) and hemoglobin levels (108.5 ± 18.2 g/L vs 125.7 ± 21.6 g/L, P < 0.001), which might have resulted from poorer nutritional condition and reduced physical recovering ability.

The nasobiliary tube retention time (5.8 ± 2.1 days vs 4.2 ± 1.6 days, P < 0.001), amount of bile drainage volume (285 ± 126 mL/24 h vs 420 ± 168 mL/24 h, P < 0.001), and patient tube tolerance (2.1 ± 0.8 vs 3.4 ± 1.2, P < 0.001) were significantly longer and poorer in the UE group. The results of the above univariate analysis showed that the risk of unplanned nasobiliary tube extubation was affected by variables such as the level of education, degree of pain, history of smoking, fasting time, liver function, nutritional indicators as well as retention time of the tube, effectiveness of the drainage, and patient tolerance together, which served as important screening basis for subsequent multivariate regression analysis and the establishment of the risk predictive model.

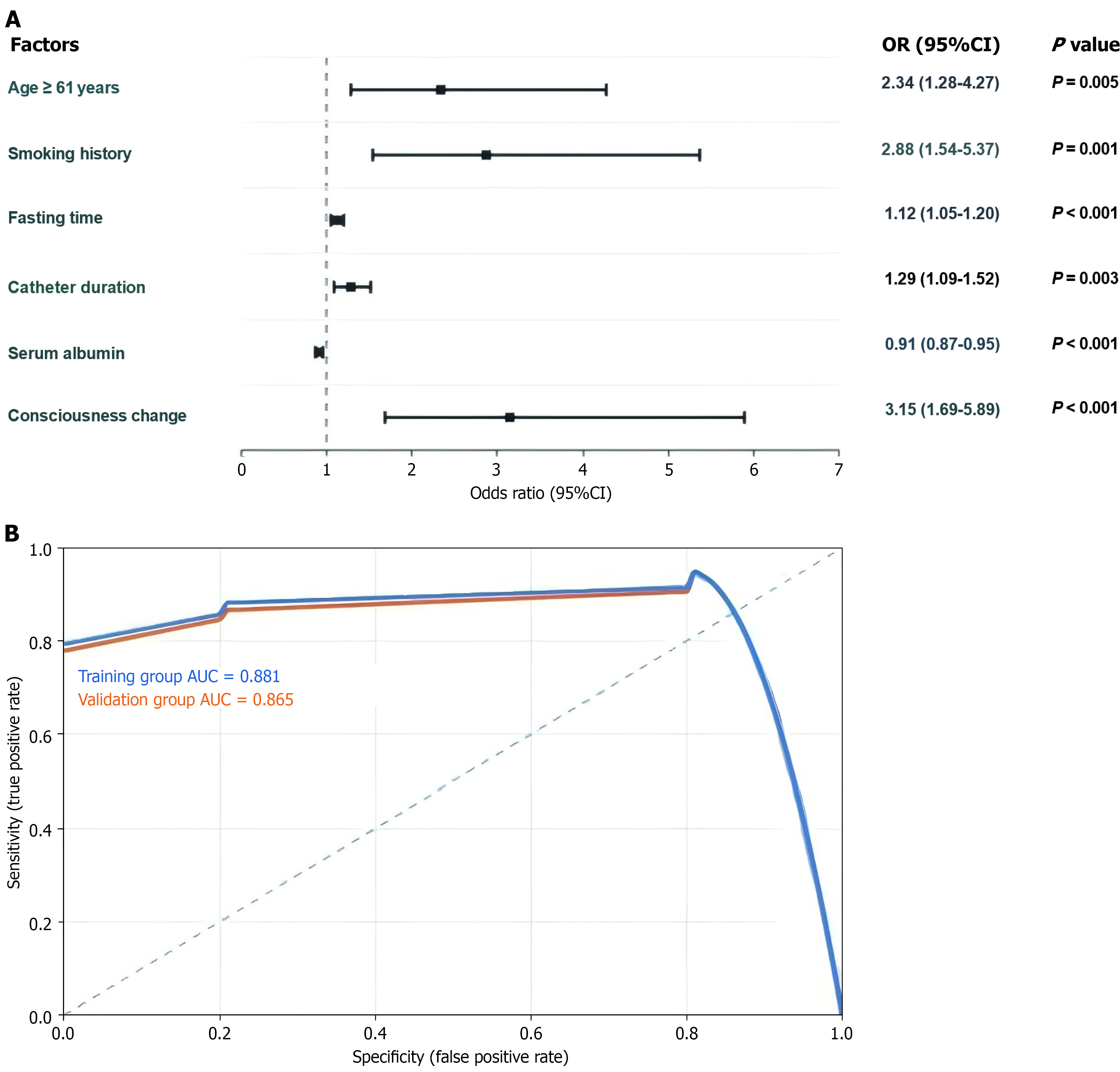

Using stepwise forward Wald method, nine statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression analysis with variable assignments as follows: Age (≥ 61 years = 1, < 61 years = 0); smoking history (yes = 1, no = 0); fasting time (continuous variable, hours); catheter duration (continuous variable, days); serum albumin (continuous variable, g/L); and consciousness change (yes = 1, no = 0). Multivariate analysis results showed that age [odds ratio (OR) = 2.341, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.285-4.267, P = 0.005], smoking history (OR = 2.876, 95%CI: 1.542-5.365, P = 0.001), fasting time (OR = 1.124, 95%CI: 1.052-1.201, P < 0.001), catheter duration (OR = 1.286, 95%CI: 1.089-1.518, P = 0.003), serum albumin (OR = 0.912, 95%CI: 0.872-0.954, P < 0.001), and consciousness change (OR = 3.152, 95%CI: 1.687-5.889, P < 0.001) were independent risk factors for unplanned nasobiliary tube extubation (Figure 3A). The final prediction model was established: P = 1/[1 + exp (-β0 + β1 × age + β2 × smoking + β3 × fasting time + β4 × catheter duration + β5 × serum albumin + β6 × consciousness change)]. Model validation showed Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test P = 0.742 (P > 0.05), indicating good model fit. ROC area under curve was 0.881 (95%CI: 0.835-0.927), optimal critical value was 0.7, model accuracy was 80.36%, sensitivity was 83.59%, specificity was 74.88%, positive predictive value was 68.2%, negative predictive value was 91.4%, and Youden index was 0.585, indicating the model has good discrimination and predictive efficacy (Figure 3B).

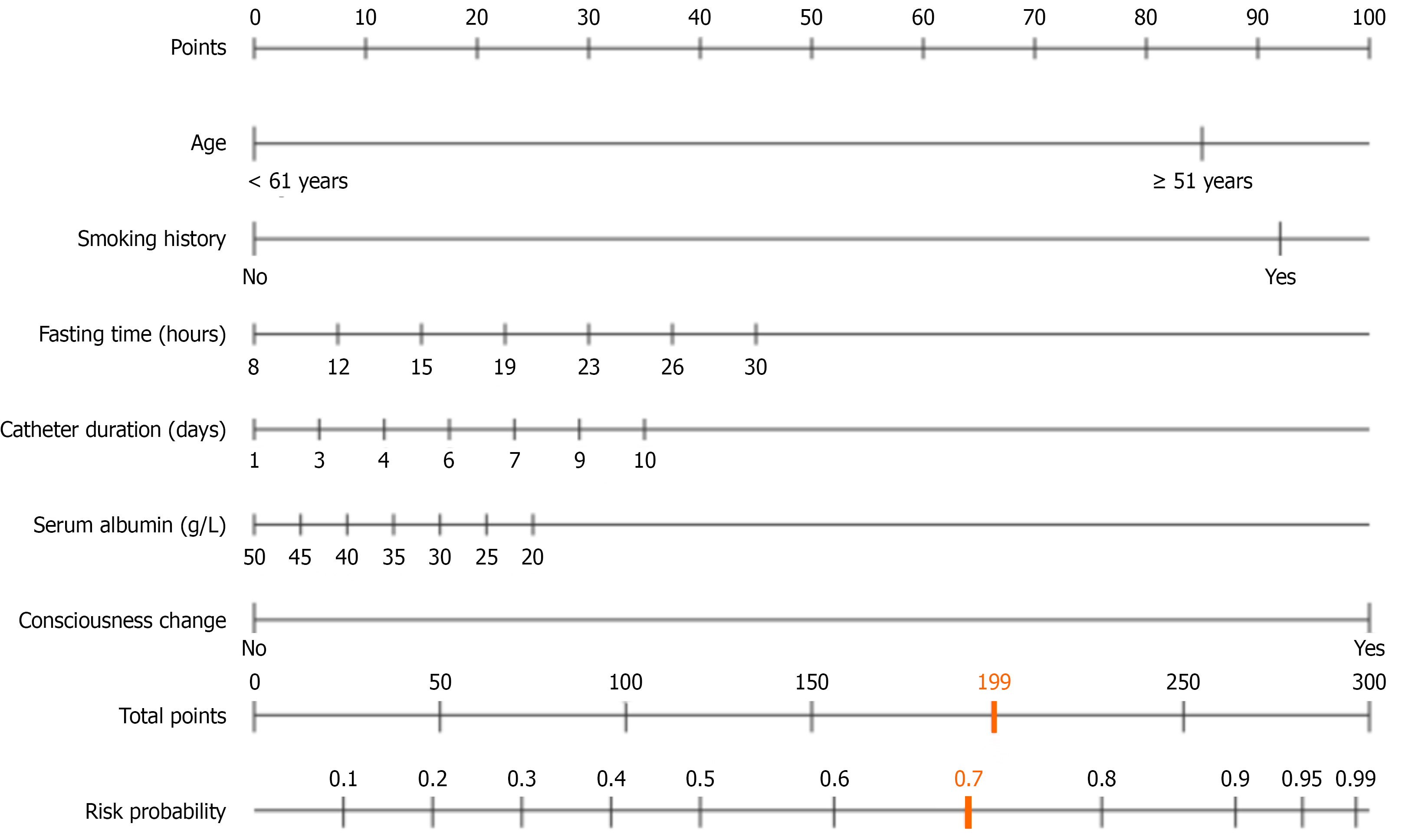

According to the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis, we formulated the nomogram risk prediction model consisting of six independent risk factors (age, smoking history, fasting time, catheter duration, serum albumin, and consciousness change) (Figure 4). The risk factors in the nomogram Model 2 were assigned a corresponding risk score according to the absolute value of the regression coefficient. The degree of influence, consciousness change (100 points), smoking history (92 points), age (≥ 61 years) (85 points), fasting time and catheter duration are treated as continuous variables, serum albumin is a protective factor with negative scoring.

Medical practitioners could contrast corresponding values on both the axes of each risk factor scoring depending on patient-specific conditions in the clinical application, aggregate all the risk factor indicator scores and obtain the total score, and determine the patient’s risk probability of UE through the axis of total score and prediction probability on total score axis. When the total score is ≥ 199 points (corresponding to prediction probability P ≥ 0.7), patients who underwent nasobiliary drainage will be judged to have a high incidence of UE and focused monitoring and preventive strategies should be put in place (Figure 4).

Nomogram prediction efficacy and stability were validated by bootstrap resampling method for 2000 internal validations. The nomogram consistency index (C-index) prediction for UE was 0.881, corrected C-index was 0.862, mean absolute error was 0.021, and the model had an excellent discriminative ability and calibration. This is an easy-to-use and accurate prediction model that is convenient for the clinical nursing staff to assess the individual risk, facilitating the early identification of patients who are high risk and the timely allocation of targeted intervention measures and greatly enhancing the safety and effectiveness of nasobiliary tube nursing.

Recent advances in minimally invasive medicine have positioned ENBD as a pivotal invention, establishing it as a crucial therapeutic approach for biliary diseases. China’s aging population and evolving lifestyle patterns have contributed to a dramatic surge in biliary disease incidence. Patients suffering from chronic choledocholithiasis, bile duct stricture, acute cholangitis, and related conditions face not only severely compromised quality of life but also potential life-threatening risks. Under these circumstances ENBD offers distinct therapeutic advantages through minimal trauma, rapid recovery, and reduced complication rates. This approach provides innovative treatment alternatives for patients, particularly benefiting elderly individuals and high-risk candidates[12-14].

Post-ENBD nursing management confronts numerous challenges with UE emerging as the most significant concern. Rather than representing merely a technical complication, UE constitutes a multifaceted problem encompassing patient safety, medical quality standards, economic implications, and legal liability risks. Accidental nasobiliary tube dis

Recent research by Ito et al[6] on the safety and effectiveness of ENBD for patients with type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis sheds a new light on the clinic application of ENBD as the results not only share similarities but also complements the present research in several ways. They included 83 patients with type 1 AIP in their study. They offered a disease-specific research design as a good adjunct to our study on a broad spectrum of patients with biliary disease. Both studies mainly discussed the safety of ENBD. Ito et al[6] (2% mild pancreatitis incidence) indicated the natural risk of the ERCP procedure, whereas the UE rate was 6.12% in our study, suggesting the nursing safety management from the po

Importantly, as a special form of pancreatitis, AIP may have different risk profiles of these factors among its population. In other words, the criteria employed by Ito et al[6] for the removal of ENBD based on contrast material outflow into duodenum was based on individualized decisions making the consideration of pathophysiological mechanisms compared with our risk prediction model based on multifactorial risk assessment. Notably, their conclusion that pancreatic segmental expansion was the independent risk factor of cholangiojejunal cystic disease stent (OR = 12.06) implies the significance of disease specificity, further supporting that our risk prediction model would be of great use for ENBD-specific management in distinct disease settings.

From a clinical point of view, the combined use of the two studies is very important. The risk prediction model established in our study could supply a standardized risk evaluation tool for actual biliary disease such as AIP while AIP-specific studies give specific suggestions for personalized management of this special set of patients. By integrating universal risk management with a disease-specific strategy, the more sophisticated ENBD safety management system could be formulated to realize the drainage effectiveness and least related complications, promoting patient safety and medical quality.

This multicenter randomized clinical trial for preventing post-ERCP cholangitis by ENBD in patients with malignant bile duct obstruction is very important to complement the evidence and meaningful difference of ENBD[5]. The study was a retrospective cohort analysis of 1008 patients who received propensity score matching to reduce selection bias and presented a more stringent epidemiological design that was relatively close to the methodology of our multicenter retrospective study. However, the research focus was quite distinct. Their study analyzed the disease spectrum limited to malignant biliary obstruction, whereas our study included patients with various biliary diseases such as choledocholithiasis and bile duct stenosis. There were basic differences in disease severity and prognosis between the two populations. Patients with malignant biliary obstruction in general have serious diseases and poor prognosis for which the severity of the disease may contribute to the surgical strategy for ENBD management and the value of risk evaluation. The head-to-head result of ENBD did not decrease the occurrence of post-ERCP cholangitis, but it reduced the recovery time and length of hospital stay. It also confirmed the clinical applicability of ENBD in certain patients, supporting better development of the personalized management strategies of ENBD for different diseases.

From a medical economics perspective, the consequences of UE are equally serious. First, emergency re-catheterization is required, increasing medical costs and prolonging the hospital stay. The average hospital stay may be extended by 3-7 days with total medical costs increased by 20%-40%. Second, new complications such as bleeding, perforation, and infection may occur during re-catheterization, further increasing treatment difficulty and costs. Additionally, UE may lead to medical disputes and legal risks, bringing additional pressure and burden to hospitals and medical staff[18-20].

For patients UE means not only physical suffering but also psychological trauma. Patient confidence in medical processes may be undermined, leading to fear and resistance toward subsequent treatment. Family members may also question medical quality, affecting harmonious doctor-patient relationships. Such psychological trauma may persist for a long time, affecting patients’ recovery process and quality of life[21-23].

From a nursing management perspective, the occurrence of UE exposes weak links in nursing work. Traditional nursing models often rely on nurses’ experiential judgment, lacking scientific risk assessment tools. This experience-based nursing approach has obvious limitations. First, different nurses have varying experience levels, leading to inconsistent nursing quality. Second, experiential judgment is easily influenced by subjective factors and may result in misjudgment. Third, facing complex and variable clinical situations, experience alone is often insufficient to accurately predict risks[24,25].

In the current nursing practice, a “non-individualized” management model is usually adopted for patients after ENBD, implementing the same nursing measures for all patients. The problem with this approach is that patients at low risk may receive too much intervention, affecting their comfort and recovery process while patients at high risk may have insufficient intervention, increasing the risk of UE. This lack of individualized nursing approach is not only inefficient but may also affect nursing effectiveness[26,27].

The introduction of risk prediction models provides new approaches to solving this problem. Through scientific statistical methods and integration of multiple risk factors, individual patient risk levels can be more accurately predicted. This quantitative risk assessment method has multiple advantages: First, it is based on large sample data and rigorous statistical analysis with high scientific validity and reliability. Second, it can provide individualized risk assessment for each patient, guiding personalized nursing strategies. Third, it can standardize nursing processes, reduce subjective factor influence, and improve nursing quality consistency[28].

The emergence of precision nursing concepts provides theoretical support for risk prediction model application. Precision nursing emphasizes developing targeted nursing plans based on patients’ individual characteristics, coinciding with risk prediction model concepts. Through risk prediction models nursing staff can identify patients who are truly high risk and concentrate limited nursing resources on patients who need them most, achieving optimal allocation of nursing resources[29].

The development of information technology also creates conditions for risk prediction model application. Modern hospital information systems can collect and process large amounts of patient data in real-time, providing data support for risk prediction models. Simultaneously, electronic assessment tools can simplify operational processes, reduce manual calculation errors, and improve work efficiency[30].

From a quality improvement perspective, risk prediction model application is an important tool for continuous quality improvement. Through regular assessment of model predictive effects, problems and deficiencies in nursing work can be discovered, providing data support for quality improvement. Simultaneously, model application can serve as an important indicator for nursing quality evaluation, promoting continuous nursing quality improvement[31].

Internationally, risk prediction model applications in healthcare are quite mature with successful application cases in pressure ulcer prevention, fall prevention, infection control, and other areas. These experiences indicate that scientific risk prediction models can not only improve nursing quality but also reduce medical costs and improve patient satisfaction. Therefore, constructing ENBD postoperative UE risk prediction models suitable for China’s national conditions has important practical significance[32].

From a patient safety perspective, UE prevention is an important component of patient safety management. The World Health Organization lists patient safety as a core element of medical quality, emphasizing prevention of medical adverse events through systematic approaches. Risk prediction model application embodies this systematic approach, identifying risks through scientific methods, implementing preventive measures, and ultimately achieving patient safety goals[33].

This study successfully constructed an ENBD postoperative UE risk prediction model through a large-sample, multicenter retrospective analysis, providing important scientific evidence for clinical nursing practice. Research results showed that the overall UE incidence was 6.12%, significantly lower than the 8%-25% reported in international literature, reflecting the relative standardization and effectiveness of China’s ENBD postoperative nursing management.

Through multivariate logistic regression analysis, we identified six independent risk factors: Age ≥ 61 years; smoking history; prolonged fasting time; prolonged catheter duration; consciousness changes; and decreased serum albumin levels. These factors cover multiple dimensions including patients’ basic characteristics, behavioral habits, clinical status, and nutritional conditions, reflecting the complexity and multifactorial nature of UE occurrence mechanisms.

The constructed risk prediction model demonstrated good predictive efficacy with an ROC area under the curve reaching 0.881, accuracy of 80.36%, sensitivity of 83.59%, and specificity of 74.88%. These indicators show the model has good discrimination and predictive ability, effectively identifying patients at high risk. Particularly noteworthy is that 70% of UEs occurred within 24-72 h postoperatively, providing nursing staff with a focused monitoring time window.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, as a retrospective study our research was inherently susceptible to selection bias, information bias from medical record documentation variations, and potential unmeasured confounding variables that may influence UE risk. Second, the study was conducted exclusively in three tertiary hospitals in Chongqing, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to other healthcare systems, geographic regions, or patient populations with different demographic characteristics and clinical practices. Third, the model employed only internal validation using bootstrap resampling, and external validation in independent populations from different institutions is needed to confirm the model’s clinical utility and broader applicability.

The nomogram model constructed based on these findings is simple to operate with total scores ≥ 199 points corresponding to high-risk thresholds, providing clinical nursing staff with intuitive, practical risk assessment tools. Application of this tool will help achieve individualized nursing, improve nursing efficiency, and ultimately reduce UE incidence, improving patient prognosis and nursing quality.

The model provided evidence-based decision-making tools that can help reduce UE incidence, improve patient safety, optimize resource allocation, and enhance nursing quality in biliary disease management.

| 1. | Choi SJ, Lee JM, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Seo YS, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD, Oh CH. A novel technique for repositioning a nasobiliary catheter from the mouth to nostril in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Endo Y, Noda H, Watanabe F, Kakizawa N, Fukui T, Kato T, Ichida K, Aizawa H, Kasahara N, Rikiyama T. Bridge of preoperative biliary drainage is a useful management for patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pancreatology. 2019;19:775-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kou K, Liu X, Hu Y, Luo F, Sun D, Wang G, Li Y, Chen Y, Lv G. Hem-o-lok clip found in the common bile duct 3 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and surgical exploration. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:1052-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maeda T, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Mizuno T, Yamaguchi J, Onoe S, Watanabe N, Kawashima H, Nagino M. Preoperative course of patients undergoing endoscopic nasobiliary drainage during the management of resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:341-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jin H, Fu C, Sun X, Fan C, Chen J, Zhou H, Liu K, Xu H. The assessment of postoperative cholangitis in malignant biliary obstruction: a real-world study of nasobiliary drainage after endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal stent. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1440131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ito T, Ikeura T, Nakamaru K, Masuda M, Nakayama S, Shimatani M, Uchida K, Takaoka M, Okazaki K, Naganuma M. Usefulness and Safety of Endoscopic Nasobiliary Drainage for Type 1 Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2025;54:e624-e629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kobori T, Suzuki G, Nakamichi Y, Serizawa H, Yamamoto S. A Case of Severe Acute Gallstone Pancreatitis With Black Ascites in a Patient Without Underlying Diseases. Cureus. 2025;17:e82807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Okuno M, Iwata K, Iwashita T, Mukai T, Shimojo K, Ohashi Y, Iwasa Y, Senju A, Iwata S, Tezuka R, Ichikawa H, Mita N, Uemura S, Yoshida K, Maruta A, Tomita E, Yasuda I, Shimizu M. Comparison of the preoperative transpapillary unilateral biliary drainage methods for the future remnant liver in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma with liver resection: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;29:102039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kiritani S, Ono Y, Sasaki T, Oba A, Sato T, Ito H, Inoue Y, Ozaka M, Sasahira N, Saiura A, Takahashi Y. Efficacy of preoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube placement for liver cancer adjacent to the hepatic hilum. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2025;410:188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gu YJ, Chen ZT, Li QY. Stent placement can achieve same prognosis as endoscopic nasobiliary drainage in treatment of bile leakage after liver transplantation. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;17:104191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gong X, Wu C, Zeng H, Chen S, Xia Y, Zhou X, Wang Y. The extracorporeal length of nasobiliary tube as a risk factor for nasobiliary tube migration. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:2625-2629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fan HS, Talbot ML. Successful management of perforated duodenal diverticulum by use of endoscopic drainage. VideoGIE. 2017;2:29-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kawashima H, Ohno E, Ishikawa T, Mizutani Y, Iida T, Yamamura T, Kakushima N, Furukawa K, Nakamura M. Endoscopic management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:1147-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kuraoka N, Ujihara T, Kasahara H, Suzuki Y, Sakai S, Hashimoto S. The efficacy of a novel integrated outside biliary stent and nasobiliary drainage catheter system for acute cholangitis: a single center pilot study. Clin Endosc. 2023;56:795-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu H, Shi C, Yan Z, Luo M. A single-center retrospective study comparing safety and efficacy of endoscopic biliary stenting only vs. EBS plus nasobiliary drain for obstructive jaundice. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:969225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mandai K, Kawamura T, Uno K, Yasuda K. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder stenting for acute cholecystitis using a novel integrated inside biliary stent and nasobiliary drainage catheter system. Endoscopy. 2022;54:E266-E267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mi N, Zhang S, Zhu Z, Yu Y, Li W, Zheng L, Chu L, Li J. Randomized Controlled Trial of Modified Nasobiliary Fixation and Drainage Technique. Front Surg. 2022;9:791945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mukai S, Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tanaka R, Tonozuka R, Sofuni A. Urgent and emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for gallstone-induced acute cholangitis and pancreatitis. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:47-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Okuno M, Iwata K, Mukai T, Iwasa Y, Ogiso T, Sasaki Y, Tomita E. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube placement through a periampullary perforation for management of intestinal leak and necrotizing pancreatitis. VideoGIE. 2023;8:75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pantzaris ND, Lord T, Sotheran R, Hutchinson J, Millson C. Nasobiliary Drain Diverted through a Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tube: A Novel Approach to Nasobiliary Drainage. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2021;15:891-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Park JK, Moon JH, Lee YN, Jo SJ, Choi MH, Lee TH, Cha SW, Cho YD, Park SH. Feasibility study of endoscopic biliary drainage under direct peroral cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope (with videos). Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1447-E1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sekine A, Nakahara K, Sato J, Michikawa Y, Suetani K, Morita R, Igarashi Y, Itoh F. Clinical Outcomes of Early Endoscopic Transpapillary Biliary Drainage for Acute Cholangitis Associated with Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Soga K. Single-pigtail plastic stent made from endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tubes in endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage: a retrospective case series. Clin Endosc. 2024;57:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sugiura R, Kuwatani M, Hayashi T, Yoshida M, Ihara H, Yamato H, Onodera M, Katanuma A; Hokkaido Interventional EUS/ERCP study (HONEST) group. Endoscopic Nasobiliary Drainage Comparable with Endoscopic Biliary Stenting as a Preoperative Drainage Method for Malignant Hilar Biliary Obstruction: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Digestion. 2022;103:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Takahashi K, Ohyama H, Ouchi M, Kan M, Nagashima H, Iino Y, Kusakabe Y, Okitsu K, Ohno I, Takiguchi Y, Kato N. Feasibility of a Single Pigtail Stent Made by Cutting a Nasobiliary Drainage Tube in Endoscopic Transpapillary Gallbladder Stenting for Acute Cholecystitis. Cureus. 2022;14:e25072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Takahashi K, Ohyama H, Takiguchi Y, Kan M, Ouchi M, Nagashima H, Ohno I, Kato N. Feasibility of Biliary Drainage Using a Novel Integrated Biliary Stent and Nasobiliary Drainage Catheter System for Acute Cholangitis. Cureus. 2023;15:e37477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tanikawa T, Kawada M, Ishii K, Urata N, Nishino K, Suehiro M, Kawanaka M, Haruma K, Kawamoto H. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided abscess drainage for non-pancreatic abscesses: A retrospective study. JGH Open. 2023;7:470-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Teh JL, Rimbas M, Larghi A, Teoh AYB. Endoscopic ultrasound in the management of acute cholecystitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;60-61:101806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu J, Wang G. Retention Time of Endoscopic Nasobiliary Drainage and Symptomatic Choledocholithiasis Recurrence After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: A Single-center, Retrospective Study in Fuyang, China. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2022;32:481-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wu X, Wu S, Tang S. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage-based saline-injection ultrasound: an imaging technique for remnant stone detection after retrograde cholangiopancreatography. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yin J, Wang D, He Y, Sha H, Zhang W, Huang W. The safety of not implementing endoscopic nasobiliary drainage after elective clearance of choledocholithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2024;24:239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang Z, Shao G, Li Y, Li K, Zhai G, Dang X, Guo Z, Shi Z, Zou R, Liu L, Zhu H, Tang B, Wei D, Wang L, Ge J. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary closure and intraoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage for choledocholithiasis combined with cholecystolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:1700-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zhou H, Liu C, Yu X, Su M, Yan J, Shi X. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage versus percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage in the treatment of advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/