Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111704

Revised: September 18, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 0.8 Hours

In the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, patients with end-stage gastrointestinal cancer (GIC) frequently bear a heavier symptom burden, see faster functional regression, and struggle with eating impairments. These further increase the de

To discuss the development of Kano model-driven ICU end-of-life care (ICU-EOLC) strategies for patients with GIC and its implications for quality of death (QoD).

This study enrolled 115 patients with end-stage GIC admitted to the ICU from June 2021 to June 2024. A Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC protocol was applied to the observation group (n = 65), contrasting with routine care in the control group (n = 50). Pre-intervention and post-intervention comparisons were made in terms of psychological well-being [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)], quality of life (QoL) [European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care Version (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL)], QoD (Chinese version of the Quality of Dying and Death in the ICU Scale), death-related attitudes [Revised Death Attitude Profile (DAP-R)], and nursing care satisfaction.

Compared with controls, patients in the observation group scored markedly lower on HADS (all domains), EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL (symptom domain), and DAP-R (escape acceptance, fear of death, and death avoidance), while achieving statistically higher scores on EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL (physical function and overall QoL dimensions), C-QDD-ICU, DAP-R (natural and approaching acceptance), and nursing care satisfaction measures.

Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC interventions significantly reduced anxiety and depression in patients with end-stage GIC, and patients’ quality of life, QoD, death-related attitudes, and nursing satisfaction were improved.

Core Tip: Focused on end-stage gastrointestinal cancer patients in intensive care unit (ICU), this research centers on con

- Citation: Zhao P, Miao L, Fu GJ, Feng JY, Deng W, Li HY. Developing Kano’s model of customer satisfaction-driven intensive care unit end-of-life care strategies for gastrointestinal cancer patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 111704

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/111704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.111704

Modern medical advances have enabled various life-sustaining measures, leading many patients with terminal conditions to depend on intensive care unit (ICU) support. However, the inevitability of death persists[1,2]. As indicated by relevant statistics, elderly patients in the ICU have high mortality rates, with approximately 51.0% dying during their ICU stays, 76.0% during hospitalization, 58% at 6 months, and 72% within 1 year[3]. Such an increased death risk among patients in the ICU is significantly affected by three or more organ failures, sepsis upon admission, and other critical factors[4]. Research has revealed the phenomenon of end-of-life isolation among patients in the ICU due to restricted visitation policies, leading to solitary deaths and compromised end-of-life experiences[5]. Additionally, 30% of global cancer diag

Family members still perceived the quality of death (QoD) among patients in the ICU as inadequate. Further care approach exploration and enhancement are imperative, considering the significant role of nursing interventions in quality of dying and death (QODD)[9]. Currently, research on QODD among patients in the ICU in China is rather limited. Broader awareness and deeper investigation are warranted despite some studies being conducted. Relevant research that investigates dying experiences from diverse viewpoints is scarce, and mixed-methods approaches remain underused[10]. Furthermore, holistic approaches to improve death care quality remain underdeveloped globally. Routine nursing interventions struggle to adequately support patients’ end-of-life experiences, requiring the development of specialized and more effective intervention frameworks[11]. The Kano model-driven nursing approach improves care delivery through a three-phase process: (1) Identifying patient requirements; (2) Categorizing these needs; and (3) Establishing priority levels. This methodology enables precisely customized treatments to fully accommodate individual care needs[12]. Yao et al[13] revealed that 75.1% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Zhejiang Province, China, were willing to adopt Kano model-driven lung rehabilitation. Notably, service pricing and insurance reimbursement ratios were the primary determinants affecting their acceptance of this novel care model, each influencing 96.2% of the patients’ decisions.

Existing literature lacks sufficient exploration of EOLC strategies for patients with GIC in the ICU and how these strategies affect their QoD. This research demonstrates clinical novelty by focusing on this understudied aspect, con

This study selected 115 patients with end-stage GIC in the ICU from June 2021 to June 2024. A Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC strategy was employed for the observation group (65 patients), whereas standard care was provided to the control group (50 patients). Eligibility criteria were: (1) Patients with end-stage GIC admitted to the ICU[14]; (2) Age of ≥ 18 years; (3) Severe condition requiring ICU treatment; (4) Estimated survival time under 1 month; and (5) Consciousness and intact verbal communication during the investigation. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Expected duration ≥ 1 month; and (2) Missing or defective clinical data.

The control group received standard care, primarily involving basic life support (e.g., assistance with repositioning, oral hygiene maintenance), catheter device management, and symptom control measures implementation.

The observation group received the Kano model-driven nursing protocol, implemented as follows. A modified Kano questionnaire was administered to assess patient needs. Attribute-based classification of nursing service items was conducted. Prioritization was subsequently established through quadrant analysis. Essential attributes (top priority) encompassed pain assessment and intervention, in addition to basic life care support. Additional important needs (key areas for improvement), requiring targeted optimization, included psychological counseling services and family-involved caregiving. Desirable but non-essential components comprised personalized wish fulfillment, spiritual care services, and memorial ceremonies (optional enhancements). To ensure effective pain management, a standardized pain management protocol was implemented, with analgesics selected according to dynamic pain assessment. Non-opioids, weak opioids, and strong opioids were administered for scores 1-3 (mild pain), 4-6 (moderate pain), and 7-10 (severe pain), respectively. Basic life care support included tailored oral care adjusted to the patient’s oral pH, 2-hourly repositioning, and pressure-redistribution dressings for bony areas. In parallel, a drainage protocol was developed for incontinence management, comprising indwelling catheters for urinary incontinence and anal drainage for fecal incontinence. Daily 30-minute psychological counseling were provided using cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques to alleviate patients’ distress. Furthermore, regular assessments were conducted to track patients’ emotional fluctuations, thereby facilitating prompt adjustments and targeted psychological support when needed. Regarding family-involved caregiving, basic nursing techniques and first-aid procedures were taught to patients’ relatives. One designated family member was allowed continuous (24/7) accompaniment. Personalized wish fulfillment was facilitated through a “bucket list” initiative, with video recording services made available for documentation. The spiritual care program supported patients in processing key life experiences by applying life retrospective therapy, complemented by individualized soundtracks following their preferences. Regarding the memorial ceremony, a commemorative booklet was created using the patient’s photos and cherished possessions, and a farewell service was arranged according to their wishes.

Psychological state evaluation: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure psychological well-being. HADS comprised two parallel subscales – anxiety and depression – each containing seven questions scored on a 0-3 scale. Thus, the total possible score for each subscale is 0-21. Scores above seven points indicated clinically relevant symptoms, categorized into mild (8-10 points), moderate (11-14 points), and severe (15-21 points)[15].

Quality of life assessment: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Ques

QoD determination: The Chinese version of the Quality of Dying and Death in the ICU Scale, a Chinese-modified version of the QODD 3.2 scale, was used to measure QoD. Our team translated and validated this instrument, confirming strong reliability and validity (Cronbach’s α = 0.892, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure = 0.836). The scale retains 21 specific items capturing ICU nurses’ perspectives on patients’ dying and death experiences [5 domains: (1) Personal autonomy; (2) Treatment preferences; (3) Social connections; (4) Perceptions of death and dignity; and (5) Spiritual needs] and four global evaluation items assessing the global assessment of dying experience (e.g., use of life-prolonging interventions, overall dying quality, quality of care provided by healthcare professionals, support from involved caregivers), slightly adjusted for cultural relevance. Nurses rate each patient’s dying process on a 0-10 scale (0: Terrible, 10: Almost perfect), with higher scores indicating superior dying experiences[17].

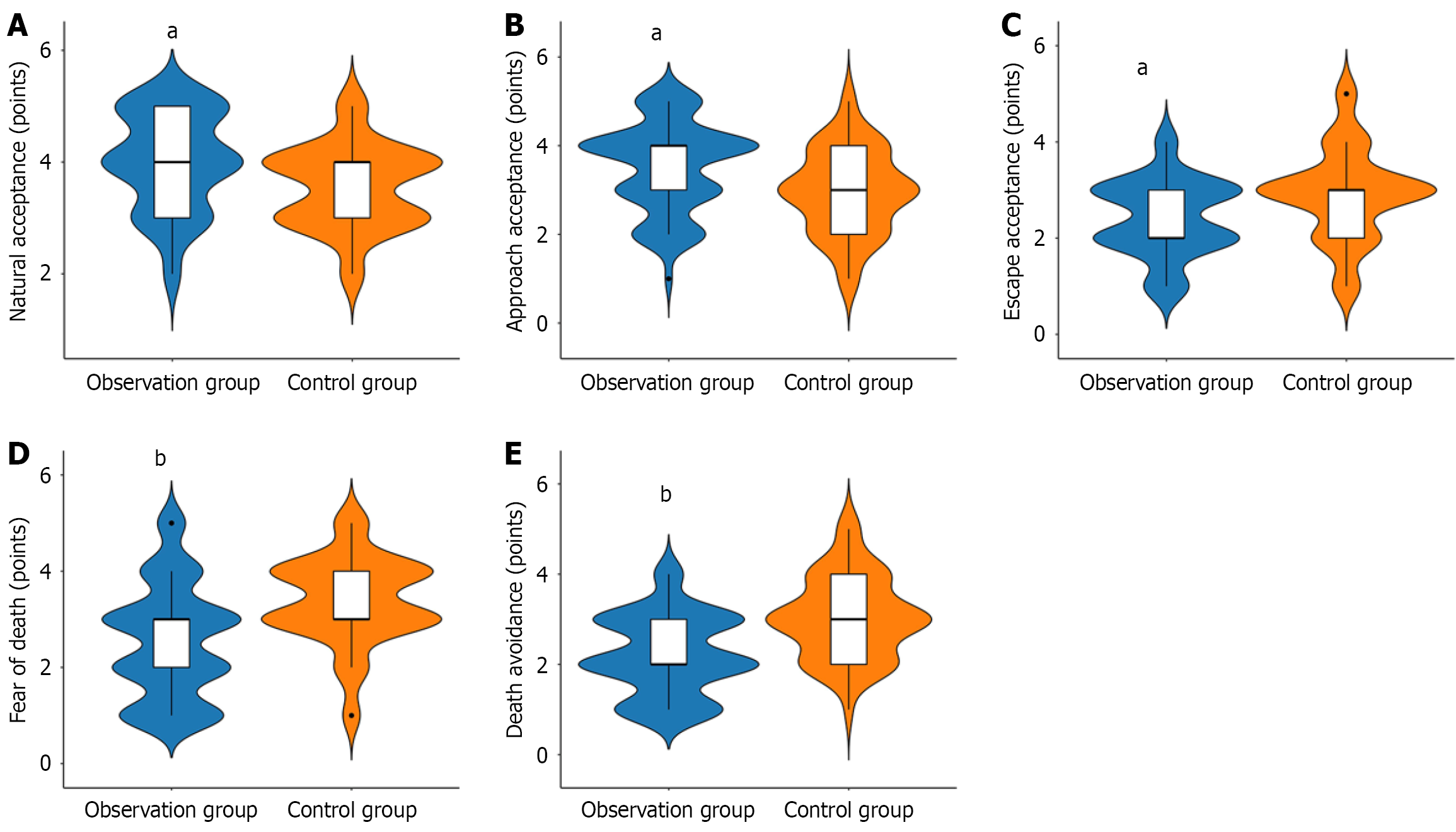

Death-related attitudes: The Revised Death Attitude Profile (DAP-R), a 32-item instrument, was used to quantify death-related attitudes across five domains: (1) Natural acceptance; (2) Approaching acceptance; (3) Escape acceptance; (4) Fear of death; and (5) Death avoidance. Participants rated statements on a 1-5 scale, with increased scores denoting greater alignment with a given dimension, thereby revealing their genuine psychological perceptions of death and their attitudes toward it[18].

Nursing care satisfaction: A self-developed satisfaction survey was applied to assess nursing satisfaction. The questionnaire adopted a 5-point Likert scale, with responses classified as “very dissatisfied” (1 point), “dissatisfied” (2 points), “fair” (3 points), “satisfied” (4 points), or “very satisfied” (5 points). Total satisfaction was calculated as the proportion of respondents who selected either “satisfied” or “very satisfied” out of the total participants[19].

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23.0 was used for data analysis. Categorical variables n (%) were compared using χ2 test (two-tailed α = 0.05). Normally distributed continuous data (mean ± SD) were analyzed using paired t-tests (within-group) or repeated-measures analysis of variance (longitudinal), supplemented by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc tests. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (two-tailed).

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the observation and control groups. The comparative assessment indicates that the two groups were statistically comparable in terms of age, sex distribution, tumor classification, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, and Karnofsky Performance Status scores, as well as previous chemotherapy treatments (P > 0.05).

| Indicators | Observation group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 50) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 56.06 ± 11.26 | 59.92 ± 10.79 | 1.856 | 0.066 |

| Sex | 0.070 | 0.791 | ||

| Male | 38 (58.46) | 28 (56.00) | ||

| Female | 27 (41.54) | 22 (44.00) | ||

| Tumor classification | 0.606 | 0.895 | ||

| Gastric cancer | 18 (27.69) | 15 (30.00) | ||

| Rectal cancer | 16 (24.62) | 13 (26.00) | ||

| Colon cancer | 14 (21.54) | 12 (24.00) | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 17 (26.15) | 10 (20.00) | ||

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (points) (mean ± SD) | 27.18 ± 6.34 | 28.18 ± 6.46 | 0.832 | 0.407 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status functional status score (points) (mean ± SD) | 39.58 ± 11.32 | 40.40 ± 14.04 | 0.347 | 0.729 |

| Previous chemotherapy treatments | 0.645 | 0.422 | ||

| No | 20 (30.77) | 12 (24.00) | ||

| Yes | 45 (69.23) | 38 (76.00) |

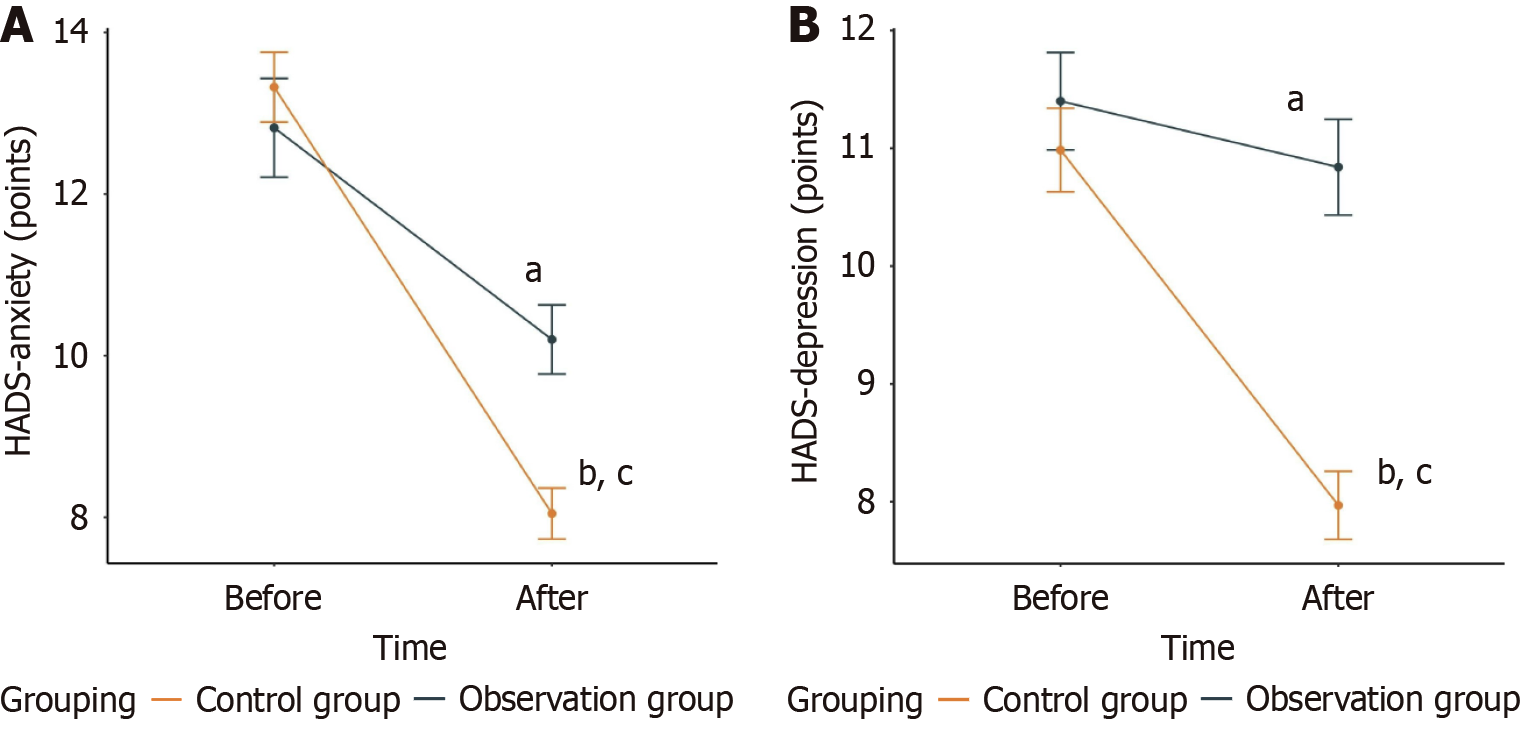

Figure 1 illustrates psychological status quantified with HADS. Baseline anxiety and depression scores did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, both groups demonstrated statistically significant improvements, with the observation group achieving superior reductions in HADS scores relative to controls (P < 0.05).

QoL was measured using the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL scale (Table 2). Baseline assessments revealed no statistically significant differences in physical function, symptom scores (pain, fatigue, and nausea/vomiting), or overall QoL (P > 0.05). Following the nursing intervention, both groups demonstrated improvements in physical function and overall QoL, with the observation group outperforming the control group (P < 0.05). Further, symptom severity decreased signifi

| Indicators | Observation group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 50) | t value | P value |

| Physical function | ||||

| Before nursing | 36.11 ± 10.14 | 38.52 ± 12.01 | 1.166 | 0.246 |

| After nursing | 56.89 ± 14.80b | 46.26 ± 14.13a | 3.894 | < 0.001 |

| Symptom scores | ||||

| Pain | ||||

| Before nursing | 61.31 ± 15.98 | 65.40 ± 13.71 | 1.446 | 0.151 |

| After nursing | 37.48 ± 11.42b | 48.68 ± 16.97a | 4.223 | < 0.001 |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Before nursing | 66.43 ± 15.17 | 66.80 ± 14.45 | 0.132 | 0.895 |

| After nursing | 51.45 ± 13.12b | 59.26 ± 12.92a | 3.186 | 0.002 |

| Nausea/vomiting | ||||

| Before nursing | 51.29 ± 14.21 | 49.18 ± 16.75 | 0.730 | 0.467 |

| After nursing | 18.82 ± 9.28b | 37.78 ± 14.64a | 8.467 | < 0.001 |

| Overall quality of life | ||||

| Before nursing | 33.65 ± 11.41 | 34.68 ± 10.74 | 0.492 | 0.624 |

| After nursing | 54.49 ± 13.63b | 40.62 ± 11.42a | 5.797 | < 0.001 |

The C-QODD-ICU scale was used to measure QoD of the two groups (Table 3). Significant differences favoring the observation group were identified in domains, including personal autonomy, treatment preferences, social connections, perceptions of death and dignity, spiritual needs, use of life-prolonging interventions, overall dying quality, quality of care provided by healthcare professionals, and support from involved caregivers (P < 0.05).

| Score (points) | Observation group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 50) | t value | P value |

| Personal autonomy | 7.45 ± 1.71 | 5.86 ± 1.75 | 4.893 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment preferences | 7.48 ± 1.82 | 5.84 ± 2.20 | 4.373 | < 0.001 |

| Social connections | 6.89 ± 1.73 | 6.18 ± 1.79 | 2.149 | 0.034 |

| Perceptions of death and dignity | 7.72 ± 1.71 | 6.76 ± 1.81 | 2.910 | 0.004 |

| Spiritual needs | 6.88 ± 1.75 | 5.96 ± 2.17 | 2.517 | 0.013 |

| Use of life-prolonging interventions | 7.08 ± 1.80 | 4.74 ± 1.58 | 7.283 | < 0.001 |

| Overall dying quality | 7.65 ± 1.65 | 6.30 ± 1.71 | 4.281 | < 0.001 |

| Quality of care provided by healthcare professionals | 8.09 ± 1.45 | 7.16 ± 1.83 | 3.041 | 0.003 |

| Support from involved caregivers | 7.82 ± 1.50 | 6.54 ± 1.66 | 4.330 | < 0.001 |

Figure 2 illustrates DAP-R scale results assessing patient life attitudes. Analysis revealed that the observation group scored statistically higher than controls in terms of natural acceptance and approach acceptance, while it obtained notably diminished scores in escape acceptance, fear of death, and death avoidance (P < 0.05).

Table 4 shows nursing satisfaction outcomes measured using a custom questionnaire. The observation group demon

| Indicators | Observation group (n = 65) | Control group (n = 50) | χ2 | P value |

| Very satisfied | 42 (64.62) | 20 (40.00) | ||

| Satisfied | 18 (27.69) | 12 (24.00) | ||

| Fair | 5 (7.69) | 10 (20.00) | ||

| Dissatisfied | 0 (0.00) | 6 (12.00) | ||

| Very dissatisfied | 0 (0.00) | 2 (4.00) | ||

| Overall satisfaction | 60 (92.31) | 32 (64.00) | 14.154 | < 0.001 |

This investigation enrolled 115 patients with terminal GIC in the ICU. A novel ICU-EOLC model, structured on the Kano concept, was implemented and assessed against conventional care. Psychological well-being, QoL, QoD, death-related attitudes, and care satisfaction assessments revealed that the Kano-driven approach outperformed standard methods, demonstrating its clinical superiority.

Patients with end-stage GIC admitted to the ICU frequently suffer from severe and incapacitating symptoms, which exacerbate psychological strain and foster negative emotional responses[20]. In this study, Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC interventions were highly effective in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with end-stage GIC in the ICU, evidenced by marked reductions in HADS scores (anxiety and depression) post-nursing. This may result from the targeted pain relief and emotional counseling to patients with end-stage GIC in ICU settings under the Kano model-based nursing approach, which promoted emotional well-being by mitigating both somatic symptoms and mental anguish[21].

To accommodate the functional constraints of patients with critically ill patients with end-stage GIC, our study used the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL for QoL evaluation. This tool’s streamlined design (5-8 minutes administration time) pre

Furthermore, our study on QoD revealed that patients with terminal GIC in ICU experienced better end-of-life outcomes when provided with nursing interventions grounded in the Kano model, with improvements in personal autonomy, treatment preferences, social connections, death and dignity perceptions, spiritual needs, use of life-prolonging interventions, overall dying quality, quality of care provided by healthcare professionals, and support from involved caregivers. This is associated with the precise identification of patient needs through the Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC protocol, which addresses three key demand categories. Results on death-related attitudes indicate that patients with terminal GIC in the ICU exhibit a more positive outlook toward death after receiving this intervention. A possible explanation is the continuous family support (24/7) facilitated by the Kano model, whereby relatives’ coope

Furthermore, implementation of Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC interventions increased satisfaction rates from 64% to 92.31% among patients with end-stage GIC, demonstrating superior acceptability and recognition compared with conventional care. This improvement may be attributed to the Kano model’s ability to address hierarchical patient needs – ranging from pain control and basic life care support to psychological counseling, family-involved caregiving, personalized wish fulfillment, spiritual care, and memorial services – thereby fostering a sense of being valued and respected[25].

To conclude, the use of Kano model-driven ICU-EOLC strategies for patients with terminal GIC contributes to anxiety/depression mitigation, QoL and QoD improvements, higher satisfaction rates, and positive shifts in death acceptance. These merits justify its wider integration into medical practice.

| 1. | Mols G. Death and Dying in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:878-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lafarge A, Dupont T, Canet E, Moreau AS, Picard M, Mokart D, Platon L, Mayaux J, Wallet F, Issa N, Raphalen JH, Pène F, Renault A, Peffault de la Tour R, Récher C, Chevallier P, Zafrani L, Darmon M, Bigé N, Azoulay E. Outcomes in Critically Ill Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation Recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;210:1017-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vallet H, Schwarz GL, Flaatten H, de Lange DW, Guidet B, Dechartres A. Mortality of Older Patients Admitted to an ICU: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:324-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mezzaroba AL, Larangeira AS, Morakami FK, Junior JJ, Vieira AA, Costa MM, Kaneshima FM, Chiquetti G, Colonheze UE, Brunello GCS, Cardoso LTQ, Matsuo T, Grion CMC. Evaluation of time to death after admission to an intensive care unit and factors associated with mortality: A retrospective longitudinal study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2022;12:121-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kynoch K, Ramis MA, McArdle A. Experiences and needs of families with a relative admitted to an adult intensive care unit: a systematic review of qualitative studies. JBI Evid Synth. 2021;19:1499-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68650] [Article Influence: 13730.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 7. | Ben-Aharon I, van Laarhoven HWM, Fontana E, Obermannova R, Nilsson M, Lordick F. Early-Onset Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract Is on the Rise-Evidence and Implications. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:538-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang Y, Huang Y, Chase RC, Li T, Ramai D, Li S, Huang X, Antwi SO, Keaveny AP, Pang M. Global Burden of Digestive Diseases: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Diseases Study, 1990 to 2019. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:773-783.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wen FH, Chiang MC, Huang CC, Hu TH, Chou WC, Chuang LP, Tang ST. Quality of dying and death in intensive care units: family satisfaction. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024;13:e1217-e1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Choi Y, Park M, Kang DH, Lee J, Moon JY, Ahn H. The quality of dying and death for patients in intensive care units: a single center pilot study. Acute Crit Care. 2019;34:192-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee SY, Chang CY. Nursing management of the critical thinking and care quality of ICU nurses: A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30:2889-2896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cao M, Peng Y, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Han M, Xie L. Optimizing nursing services for orthopaedic trauma patients using SERVQUAL and Kano models. Sci Rep. 2025;15:12850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yao X, Li J, He J, Zhang Q, Yu Y, He Y, Wu J, Tang W, Ye C. A Kano model-based demand analysis and perceived barriers of pulmonary rehabilitation interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0290828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Washington MK, Goldberg RM, Chang GJ, Limburg P, Lam AK, Salto-Tellez M, Arends MJ, Nagtegaal ID, Klimstra DS, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Lazar AJ, Odze RD, Carneiro F, Fukayama M, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Diagnosis of digestive system tumours. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:1040-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yokoyama T, Tamura T, Nishida K, Ito R, Nishiwaki K. Anxiety evaluated by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a predictor of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a pilot study. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2024;86:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pilz MJ, Thurner AMM, Storz LM, Krepper D, Giesinger JM. The current use and application of thresholds for clinical importance of the EORTC QLQ-C30, the EORTC CAT core and the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL- a systematic scoping review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2025;23:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reinink H, Geurts M, Melis-Riemens C, Hollander A, Kappelle J, van der Worp B. Quality of dying after acute stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Han H, Ye Y, Zhuo H, Liu S, Zheng F. Death attitudes and associated factors among health professional students in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1174325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Deng YH, Yang YM, Ruan J, Mu L, Wang SQ. Effects of nursing care in fast-track surgery on postoperative pain, psychological state, and patient satisfaction with nursing for glioma. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:5435-5441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S. Anxiety and depression prevalence in digestive cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;13:e235-e243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Roberts RL, Ledermann K, Garland EL. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement improves negative emotion regulation among opioid-treated chronic pain patients by increasing interoceptive awareness. J Psychosom Res. 2022;152:110677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tur P, Oldenburger E, Bottomley A, Cella D, Lee SF, Chan AW, Marta GN, Jacobs T, Chow E, Wong HCY, Rembielak A. Evaluation of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL and the FACIT-PAL-14 in assessing the quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2025;19:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang JM, Zhang MR, Yang CH, Li Y. The meaning of life according to patients with advanced lung cancer: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2022;17:2028348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sweeney MM, Nayak S, Hurwitz ES, Mitchell LN, Swift TC, Griffiths RR. Comparison of psychedelic and near-death or other non-ordinary experiences in changing attitudes about death and dying. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0271926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xiao J, Ng MSN, Yan T, Chow KM, Chan CWH. How patients with cancer experience dignity: An integrative review. Psychooncology. 2021;30:1220-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/