Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.112557

Revised: August 14, 2025

Accepted: September 9, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 118 Days and 5.6 Hours

Compared to standard hospital meals, nutritional intervention using recovery K5 (RK5), a concentrated liquid diet, offers a comprehensive immunonutritional profile, suggesting its potential effectiveness in preventing surgical site infections (SSIs) after gastrointestinal surgery.

To investigate the usefulness of RK5 in patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery, focusing on postoperative infections and nutritional status.

This single-center, open-label, randomized, parallel-group comparative trial was conducted at Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nippon Medical School Hospital, between February 2023 and August 2024. Forty patients with colorectal cancer were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the nutritional intervention or the control group. The intervention group received 800 kcal/day of RK5 admi

No cases of remote infection were observed. SSIs occurred in one of the 17 patients (5.9%) in the intervention group and six of the 18 patients (33.3%) in the control group, with an odds ratio of 0.125 (95% confidence interval: 0.013-1.181, P = 0.0695). Energy intake and percentage of target energy intake were significantly higher in the intervention group. No significant differences were observed bet

Supplemental nutrition using RK5 may help prevent SSIs in patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery and should be considered as a potential option for perioperative nutritional management.

Core Tip: This study assessed the clinical utility of recovery K5 (RK5), a concentrated liquid formula, in patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery. Patients receiving RK5 in addition to standard meals were compared with those receiving standard meals alone. RK5 supplementation improved target energy intake achievement and showed a trend toward reduced surgical site infections.

- Citation: Shinji S, Yamada T, Matsuda A, Uehara K, Yokoyama Y, Takahashi G, Iwai T, Miyasaka T, Kanaka S, Hayashi K, Yoshida H. Clinical utility of a novel concentrated enteral formula in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(11): 112557

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i11/112557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.112557

Postoperative infections are serious complications associated with surgical procedures and perioperative management. These infections are generally classified into surgical site infections (SSIs) and remote infections. Among the early postoperative complications, SSIs are the most common[1]. SSIs in surgical patients can lead to symptoms such as fever and pain, and are associated with prolonged hospitalization, delayed recovery, and increased healthcare costs[2]. To prevent postoperative infections, perioperative management strategies, including prophylactic antibiotic administration, various preoperative and intraoperative procedures, and strict postoperative glycemic control, are considered effective[3]. However, among gastrointestinal surgeries, colorectal procedures carry a particularly high risk of SSIs due to contamination of the surgical field by the intestinal microbiota[4], necessitating stricter preventive measures.

Malnutrition is a known risk factor of postoperative mortality and complications associated with gastrointestinal surgery. In gastrectomy patients, the incidence of SSIs is significantly higher among malnourished individuals than among those with a good nutritional status[5]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer surgery, nutritional risk, as assessed using the nutritional risk screening 2002, has been linked to an increased SSI incidence[6]. While perioperative nutritional support has been shown to help prevent SSIs in malnourished patients with gastric cancer[5,7], systematic reviews suggest that although nutritional support improves nutritional status and quality of life, the overall evidence is limited due to the small number and design of available studies[8]. In contrast, in patients with adequate nutritional status, supplementation may shorten the hospital stay but has not been shown to be effective in preventing SSIs[9,10]. Nonetheless, for malnourished patients undergoing elective gastrointestinal surgery, improving their nutritional status is recommended because of their higher risk of SSI[3,10].

Recovery K5 (RK5) is a concentrated liquid formula developed by Nutri Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. It contains a balanced combination of soy and milk proteins, in addition to collagen peptides, making it suitable for nutritional support during both the stress and recovery phases. Additionally, it contains L-carnitine, which is necessary for lipid metabolism; palatinose and galactooligosaccharides as carbohydrates; and various vitamins and minerals. Compared to standard hospital meals, RK5 offers a comprehensive immunonutritional profile, suggesting its potential effectiveness in preventing SSIs after gastrointestinal surgery. In this study, we evaluated the clinical utility of RK5 by comparing the incidence of postoperative infections, improvement in nutritional status, and various clinical parameters between elective gastrointestinal surgery patients receiving RK5 supplementation in addition to standard hospital meals and a control group receiving standard meals alone.

This single-center, open-label, randomized, parallel-group comparative trial was conducted at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nippon Medical School Hospital, between February 2023 and August 2024. The study enrolled patients scheduled to undergo elective colorectal cancer surgery in our department. Eligibility was confirmed, and written informed consent was obtained at the time of admission (from at least 2 days to 1 month prior to surgery). Patients were then randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the nutritional intervention or control group using a block randomization method prior to admission. The control group received a standard hospital diet starting 2 days before surgery (the day of admission), with an energy provision of 25-30 kcal/kg/day based on body weight. The intervention group received 800 kcal/day of RK5 administered orally in place of breakfast and dinner (400 kcal per serving) 2 days prior to surgery. On the day of surgery, all patients were required to fast. Only fluid was allowed on postoperative day 1 (POD1). On POD2, patients in the intervention group resumed RK5 only, followed by gradual reintroduction of the standard diet in combination with RK5 until they reached the maintenance level, which continued until POD7. In the control group, RK5 was not administered, and patients resumed only the standard hospital diet once postoperative maintenance intake was reached, which was continued through to POD7. In both groups, the study intervention period spanned 10 days: From 2 days before surgery to 7 days postoperatively, including the day of surgery. This was followed by a 30-day post-intervention observation period, starting on the day after study completion or withdrawal.

RK5 is a concentrated liquid formula containing 400 kcal per 330 mL, as detailed in Table 1. RK5 was selected as a study material because it provides excellent nutritional balance and can be taken orally. No restrictions were imposed on the use of antibiotics; however, cefmetazole was administered on the day of and the next day after surgery. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nippon Medical School Hospital (No. M-2022-048) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. All participants were given a full explanation of the study and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

| Component | |

| Energy | 400 kcal |

| Protein | 20.0 g |

| Fat | 10.7 g |

| Carbohydrates | 60.4 g |

| Carbohydrate | 52.4 g |

| Dietary fiber | 8.0 g |

| Sodium equivalent | 1.68 g |

| Sodium | 660 mg |

| Potassium | 540 mg |

| Calcium | 280 mg |

| Magnesium | 140 mg |

| Phosphorus | 320 mg |

| Iron | 3.2 mg |

| Zinc | 4.8 mg |

| Copper | 0.40 mg |

| Manganese | 1.68 mg |

| Iodine | 44 μg |

| Selenium | 28 μg |

| Chromium | 20.0 μg |

| Molybdenum | 20 μg |

| Vitamin A | 452 μg |

| Vitamin D | 3.6 μg |

| Vitamin E | 5.6 mg |

| Vitamin K | 64 μg |

| Vitamin B1 | 0.88 mg |

| Vitamin B2 | 0.88 mg |

| Niacin | 11.6 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.80 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 2.8 μg |

| Folic acid | 152 μg |

| Pantothenic acid | 4.40 mg |

| Biotin | 29.2 μg |

| Vitamin C | 80 mg |

| Water | 264 g |

| Collagen peptide | 4 g |

| Galactooligosaccharide | 0.8 g |

| Chlorine | 600 mg |

| Enterococcus faecalis (heat-sterilized bacteria) | 240 billion pieces |

| L-carnitine | 80 mg |

Patients scheduled for elective gastrointestinal surgery at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nippon Medical School Hospital, were screened for eligibility. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients scheduled to undergo elective colorectal cancer surgery; (2) Patients able to consume oral nutrition; and (3) Patients aged 20 years or older and younger than 75 years. The exclusion criteria were: (1) ≥ 10% weight loss compared to usual body weight within the past 6 months; (2) Presence of dysphagia; (3) Hepatic dysfunction, classified as Child-Pugh class C; (4) Respiratory dysfunction, defined as arterial oxygen partial pressure < 70 mmHg; (5) Renal dysfunction, defined as serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL; (6) Cardiac dysfunction, classified as New York Heart Association functional class > 3; (7) Pregnancy; (8) Systemic infection; (9) Immunodeficiency; (10) Patients judged to require central venous nutrition; and (11) Patients with comorbidities that would necessitate or potentially necessitate restriction of energy intake during hospitalization. All eligible patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Clinical laboratory tests (including hematology, blood biochemistry, and body composition), specialized blood tests [CD4/CD8 ratio, natural killer cell activity, interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and prealbumin], and vital signs (height, body weight, mid-upper arm circumference, blood pressure, pulse rate, and body temperature) were measured at the time of surgery scheduling, preoperatively, and at the end of the study period. General clinical findings, including bowel movement frequency and the occurrence of diarrhea, as well as adverse events, including postoperative complications, were monitored daily throughout the study period. During the post-intervention observation period, adverse events, including postoperative complications, were also assessed. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the individual’s height and weight.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of postoperative infections during the study period. SSIs were assessed based on the definitions provided by the Japan Society for Environmental Infections SSI surveillance guidelines[11], including superficial incisional SSI, deep incisional SSI, and organ/space SSI, which were collectively evaluated. The secondary endpoints were nutritional status and bowel function. Nutritional status was assessed using serum albumin level, BMI, and muscle mass in different body regions, whereas bowel function was evaluated based on the frequency of bowel movements and the occurrence of diarrhea.

Because this was an exploratory clinical study with no available reference data for sample size calculation, a formal estimation of the target sample size was not conducted. However, a target of at least 15 patients per group was set based on the number of patients expected to be enrolled at the study site. Continuous variables presented in the text or tables were expressed as mean ± SD; for variables not following a normal distribution, values were presented as quartiles. The analysis populations included the full analysis set (FAS), per-protocol set, and safety analysis set, with primary analyses performed using the FAS. Comparisons between the intervention and control groups were conducted using the unpaired t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Fisher’s exact test, or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, as appropriate. The incidence of SSIs was compared using a logistic regression model to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (Statistical Analysis System Institute Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

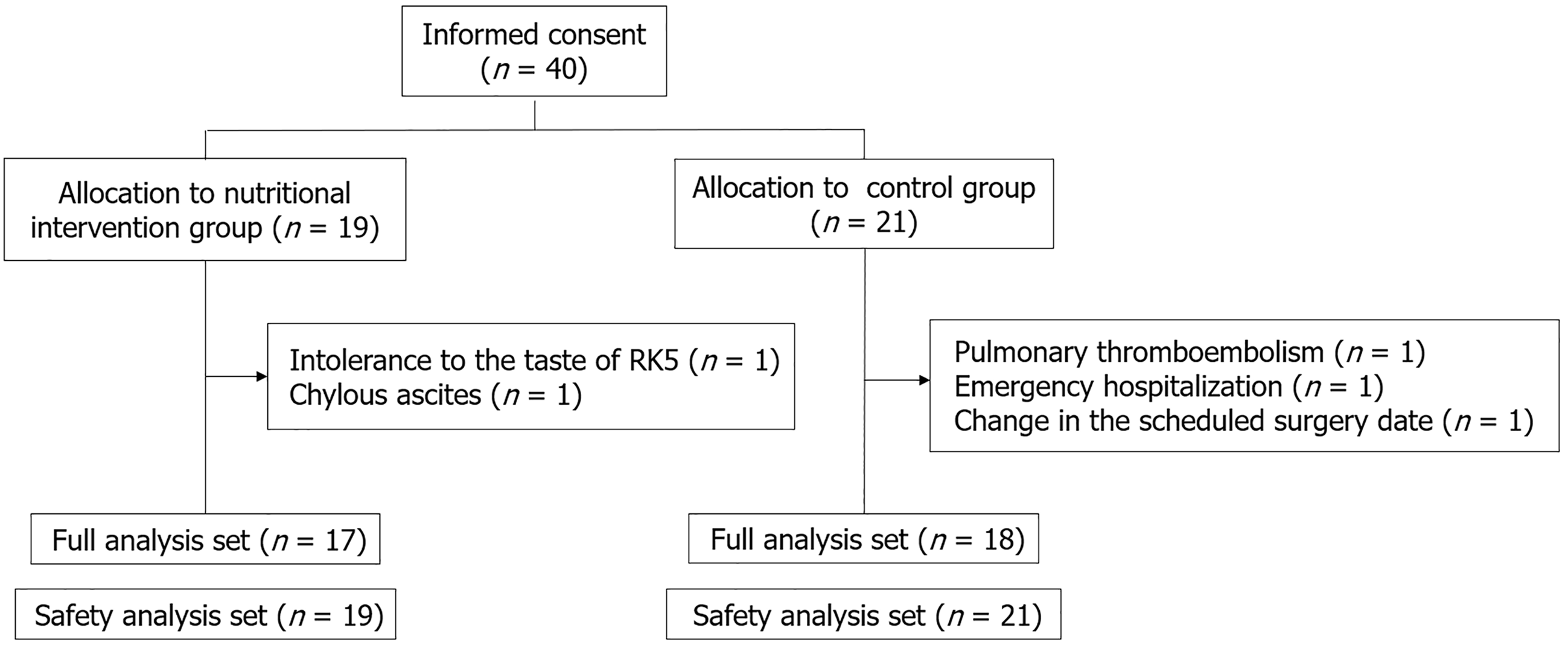

Of the 40 patients who provided informed consent to participate in the study (Figure 1), two in the nutritional intervention group and three in the control group discontinued the study. In the intervention group, one patient withdrew due to intolerance to the taste of RK5, and one patient withdrew due to chylous ascites. In the control group, one patient discontinued treatment due to pulmonary thromboembolism, one due to emergency hospitalization, and one due to a change in the scheduled surgery date. Seventeen patients in the nutritional intervention group and 18 patients in the control group completed the study protocol and were included in the FAS. The safety analysis set included 19 patients in the intervention group and 21 patients in the control group.

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. In both the nutritional intervention and control groups, most patients were male (76% vs 72%). The mean ages were 61.3 ± 7.3 years in the intervention group and 58.8 ± 11.4 years in the control group. The mean BMI was 22.1 ± 3.2 kg/m2 in the intervention group and 23.6 ± 3.8 kg/m2 in the control group. All patients underwent surgery for colorectal cancer. The distribution of tumor location (colon vs rectum) was 58.8% and 41.2% in the intervention group and 44.4% and 55.6% in the control group. The mean operative time was 199.1 ± 89.3 minutes in the intervention group and 212.4 ± 57.5 minutes in the control group.

| Parameter | Nutritional intervention group (n = 17) | Non-intervention group (n = 18) | P value |

| Gender, men/female | 13/4 (76/24) | 13/5 (72/28) | 1.00001 |

| Age, year, mean ± SD (median, range) | 61.3 ± 7.3 (61, 44-73) | 58.8 ± 11.4 (62, 34-73) | 0.45662 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD (median, range) | 22.1 ± 3.2 (22.7, 16.3-26.9) | 23.6 ± 3.8 (22.9, 18.2-33.0) | 0.21292 |

| ASA | 0.49513 | ||

| 1 | 1 (5.9) | 2 (11.1) | |

| 2 | 15 (88.2) | 12 (66.7) | |

| 3 | 1 (5.9) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Tumor location | 0.60374 | ||

| C | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.1) | |

| A | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.6) | |

| T | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| D | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.6) | |

| S | 4 (23.5) | 3 (16.7) | |

| RS | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Ra | 1 (5.9) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Rb | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Tumor size, mm, mean ± SD (median, range) | 34.4 ± 19.9 (35, 11-75) | 35.9 ± 18.0 (33, 0-77) | 0.81902 |

| UICC-TNM stage | 0.83783 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| I | 6 (35.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| II | 3 (17.6) | 7 (38.9) | |

| III | 7 (41.2) | 7 (38.9) | |

| IV | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | |

| T category | 0.43663 | ||

| T0 | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | |

| T1 | 5 (29.4) | 1 (5.6) | |

| T2 | 3 (17.6) | 3 (16.7) | |

| T3 | 7 (41.2) | 12 (66.7) | |

| T4 | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.6) | |

| N category | 0.43193 | ||

| N0 | 9 (52.9) | 11 (61.1) | |

| N1 | 4 (23.5) | 5 (27.8) | |

| N2 | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.1) | |

| M category | 0.30353 | ||

| M0 | 16 (94.1) | 18 (100.0) | |

| M1 | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Any comorbidity | 9 (52.9) | 12 (66.7) | 0.49981 |

| Hypertension | 5 (29.4) | 6 (33.3) | 1.00001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) | 0.48571 |

| Arrhythmia | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.48571 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) | 1.00001 |

| Asthma | 2 (11.8) | 3 (16.7) | 1.00001 |

| COPD | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.48571 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (5.9) | 5 (27.8) | 0.17741 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 (23.5) | 7 (38.9) | 0.47051 |

| Smoking | 9 (52.9) | 11 (61.1) | 0.73801 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 3 (17.6) | 6 (33.3) | 0.44301 |

| Operative time, minute, mean ± SD (median, range) | 199.1 ± 89.3 (174.0, 117-453) | 212.4 ± 57.5 (202.5, 115-328) | 0.59942 |

| Temporary loop ileostomy | 2 (11.8) | 5 (27.8) | 0.40181 |

| Postoperative stay, day, mean ± SD (median, range) | 10.3 ± 4.6 (9, 8-27) | 10.8 ± 3.5 (9, 8-18) | 0.69602 |

No remote infections were observed in any group during the study period. However, SSIs occurred in one of the 17 patients (5.9%) in the nutritional intervention group and in six of the 18 patients (33.3%) in the control group. The odds ratio for SSI in the intervention group was 0.125 (95% confidence interval: 0.013-1.181; P = 0.0695) (Table 3). There were no observed associations between SSI incidence and known risk factors, such as American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status ≥ 3, diabetes mellitus, or malnutrition (as assessed by the controlling nutritional status score), in either group.

| SSI | |

| Nutritional intervention group (n = 17) | 1 (5.9) |

| Non-intervention group (n = 18) | 6 (33.3) |

| Odds ratio | 0.125 |

| 95%CI | 0.013-1.181 |

| P value | 0.0695 |

The total energy intake during the study period was significantly higher in the nutritional intervention group than in the control group (9946.3 ± 3710.1 kcal vs 7697.0 ± 2748.4 kcal, P = 0.049). The proportion of energy intake relative to the estimated target energy requirement was also significantly higher in the intervention group (78.1% ± 28.6%) compared to the control group (59.3% ± 20.5%, P = 0.032). Among patients who completed oral intake without forced interruption (e.g., due to fasting requirements), nine of the 17 patients (52.9%) in the intervention group and five of the 18 patients (27.8%) in the control group met this criterion. In these patients, total energy intake and percentage of target energy achieved were significantly higher in the intervention group (12123.3 ± 1551.8 kcal and 97.2% ± 5.4%, respectively) compared with the control group (9486.3 ± 2261.4 kcal and 74.7% ± 13.7%; P = 0.023 and P = 0.001, respectively). The association between preoperative energy intake and SSI incidence showed a trend toward a difference between the two groups (P = 0.0955; Table 4).

| Nutritional intervention group (n = 17) | Non-intervention group (n = 18) | Comparison of odds ratio between groups | |||||

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value | P value | |

| Oral intake pre-op-2 | 0.58 | 0.24-1.32 | 0.1849 | 1.06 | 0.81-1.40 | 0.6705 | 0.1637 |

| Oral intake pre-op-1 | 0.78 | 0.57-1.06 | 0.1176 | 1.04 | 0.86-1.26 | 0.6562 | 0.0994 |

| Oral intake pre-op-2 to-1 | 0.88 | 0.72-1.08 | 0.2228 | 1.00 | 0.91-1.13 | 0.6231 | 0.0955 |

As shown in Table 5, several parameters showed significant changes from the day of surgery to the end of the study in both the nutritional intervention and control groups. TNF-α and C-reactive protein levels increased postoperatively; however, there were no significant differences in the degree of change between groups. Nutritional status markers (serum albumin level, BMI, and muscle mass in different body regions) remained relatively stable from the postoperative period to the end of the study in both groups. The controlling nutritional status score, a marker of nutritional risk, decreased from 4.1 ± 2.5 to 3.6 ± 2.6 in the intervention group and from 3.7 ± 1.9 to 3.4 ± 2.1 in the control group, with no significant differences observed between groups.

| Nutritional intervention group (n = 17) | Non-intervention group (n = 18) | Comparison of difference from pre-op to post-op between groups | |||||

| Pre-op | Post-op | P value1 | Pre-op | Post-op | P value1 | P value | |

| WBC, ×103/μL, mean ± SD | 4.56 ± 1.42 | 6.71 ± 3.13 | 0.0041 | 5.67 ± 1.72 | 7.40 ± 2.36 | 0.0154 | 0.6685 |

| Neutro, %, mean ± SD | 69.2 ± 7.0 | 69.8 ± 9.2 | 0.8050 | 68.0 ± 6.4 | 71.0 ± 6.8 | 0.1703 | 0.4236 |

| Lympho, %, mean ± SD | 21.6 ± 6.6 | 19.0 ± 7.7 | 0.1673 | 22.7 ± 6.4 | 18.9 ± 5.6 | 0.0289 | 0.5453 |

| Mono, %, mean ± SD | 5.65 ± 1.87 | 5.81 ± 1.85 | 0.7246 | 6.29 ± 1.08 | 5.99 ± 1.23 | 0.4306 | 0.4213 |

| Eosino, %, geo-mean (CV) | 2.37 (41.6) | 3.98 (35.9) | 0.0058 | 1.96 (47.5) | 2.94 (46.0) | 0.0704 | 0.4393 |

| Baso, %, mean ± SD | 0.69 ± 0.39 | 0.67 ± 0.38 | 0.8978 | 0.63 ± 0.28 | 0.47 ± 0.21 | 0.0543 | 0.1971 |

| RBC, ×106/μL, mean ± SD | 3.83 ± 0.65 | 4.14 ± 0.63 | 0.0020 | 3.83 ± 0.59 | 4.10 ± 0.70 | 0.0048 | 0.7676 |

| Hb, g/dL, mean ± SD | 11.7 ± 1.8 | 12.6 ± 1.6 | 0.0038 | 11.7 ± 1.9 | 12.5 ± 2.2 | 0.0104 | 0.7380 |

| HCT, %, mean ± SD | 35.5 ± 5.2 | 38.0 ± 4.7 | 0.0052 | 35.4 ± 5.1 | 37.5 ± 5.9 | 0.0191 | 0.6707 |

| PLT, ×103/μL, mean ± SD | 197.6 ± 45.3 | 286.5 ± 69.4 | < 0.0001 | 214.9 ± 74.3 | 306.0 ± 66.4 | < 0.0001 | 0.9039 |

| AST, U/L, geo-mean (CV) | 15.4 (9.5) | 20.2 (10.7) | 0.0043 | 20.6 (14.0) | 20.5 (12.4) | 0.9598 | 0.0324 |

| ALT, U/L, geo-mean (CV) | 12.9 (15.8) | 19.9 (19.9) | 0.0041 | 18.4 (23.0) | 21.4 (18.2) | 0.2852 | 0.1556 |

| ALP, U/L, mean ± SD | 60.3 ± 18.6 | 76.5 ± 26.9 | 0.0005 | 64.8 ± 19.4 | 77.1 ± 24.2 | 0.0048 | 0.5161 |

| CK, U/L, geo-mean (CV) | 54.6 (9.5) | 46.7 (14.7) | 0.1557 | 68.0 (11.6) | 43.1 (18.3) | 0.0001 | 0.0558 |

| Amylase, U/L, geo-mean (CV) | 68.5 (9.8) | 99.1 (18.5) | 0.0038 | 47.8 (9.0) | 55.5 (13.8) | 0.2329 | 0.1966 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.64 ± 0.28 | 0.52 ± 0.23 | 0.0341 | 0.73 ± 0.34 | 0.61 ± 0.27 | 0.0191 | 0.8955 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 182.2 ± 38.0 | 189.4 ± 51.2 | 0.3596 | 161.2 ± 33.8 | 156.6 ± 30.4 | 0.3651 | 0.2008 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 114.1 ± 36.4 | 116.8 ± 35.2 | 0.7775 | 94.7 ± 26.0 | 89.9 ± 26.5 | 0.4003 | 0.4243 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 44.7 ± 13.7 | 39.6 ± 12.8 | 0.0015 | 44.2 ± 12.4 | 38.8 ± 9.8 | 0.0008 | 0.8211 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 117.4 ± 51.5 | 133.3 ± 40.0 | 0.0704 | 111.9 ± 64.7 | 135.0 ± 43.9 | 0.0628 | 0.9739 |

| Na, mmol/L, mean ± SD | 140.9 ± 2.4 | 139.9 ± 2.3 | 0.2099 | 142.1 ± 2.0 | 139.1 ± 3.7 | 0.0002 | 0.0595 |

| Cl, mmol/L, mean ± SD | 106.9 ± 4.6 | 102.2 ± 3.0 | 0.0001 | 108.1 ± 3.2 | 102.7 ± 4.2 | < 0.0001 | 0.6757 |

| K, mmol/L, mean ± SD | 3.71 ± 0.45 | 4.19 ± 0.39 | 0.0002 | 3.89 ± 0.43 | 4.37 ± 0.35 | 0.0001 | 0.9770 |

| BUN, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 11.3 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 3.4 | 0.5041 | 11.4 ± 3.7 | 14.6 ± 6.2 | 0.0116 | 0.1776 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.15 | 0.0846 | 0.76 ± 0.21 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | 0.1388 | 0.8287 |

| Total protein, g/dL, mean ± SD | 5.62 ± 0.59 | 6.44 ± 0.48 | < 0.0001 | 5.68 ± 0.67 | 6.45 ± 0.77 | < 0.0001 | 0.8087 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.37 ± 0.43 | 3.51 ± 0.52 | 0.2014 | 3.43 ± 0.43 | 3.59 ± 0.54 | 0.1197 | 0.8595 |

| eGFR, mL/minute/1.73 m2, mean ± SD | 79.1 ± 13.4 | 73.2 ± 11.8 | 0.0638 | 80.3 ± 19.4 | 74.7 ± 16.3 | 0.0686 | 0.9499 |

| CRP, mg/dL, geo-mean (CV) | 0.08 (-39.9) | 1.11 (1161.8) | < 0.0001 | 0.11 (-56.3) | 1.03 (3756.7) | < 0.0001 | 0.4785 |

| Glucose, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 103.8 ± 16.8 | 103.1 ± 20.8 | 0.8662 | 107.2 ± 12.3 | 107.1 ± 18.1 | 0.9623 | 0.9323 |

| Prealbumin, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 22.2 ± 4.9 | 20.0 ± 5.3 | 0.1799 | 21.1 ± 6.4 | 20.4 ± 8.5 | 0.5151 | 0.6254 |

| NK cell activity, %, mean ± SD | 31.5 ± 10.7 | 28.9 ± 12.7 | 0.4505 | 38.1 ± 14.4 | 30.9 ± 18.5 | 0.0314 | 0.2922 |

| CD4, %, mean ± SD | 44.1 ± 12.1 | 42.1 ± 7.9 | 0.2782 | 44.9 ± 9.5 | 45.9 ± 9.7 | 0.8166 | 0.3551 |

| CD8, %, mean ± SD | 35.9 ± 11.2 | 33.2 ± 10.6 | 0.0446 | 30.8 ± 8.0 | 29.7 ± 9.2 | 0.3464 | 0.4438 |

| CD4/CD8 ratio, mean ± SD | 1.47 ± 0.75 | 1.43 ± 0.67 | 0.7161 | 1.57 ± 0.61 | 1.74 ± 0.73 | 0.1822 | 0.2268 |

| INF-γ, IU/mL, mean ± SD | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.7982 | 0.13 ± 0.12 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.5087 | 0.5170 |

| TNF-α, IU/mL, geo-mean (CV) | 0.66 (-262.8) | 0.93 (300.8) | 0.0002 | 0.68 (-311.3) | 0.93 (190.0) | 0.0028 | 0.5537 |

| Body composition analysis | |||||||

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 21.3 ± 3.4 | 20.8 ± 3.4 | 0.0010 | 23.6 ± 3.9 | 22.8 ± 3.8 | < 0.0001 | 0.4039 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 59.7 ± 13.1 | 58.4 ± 12.7 | 0.0010 | 65.6 ± 12.9 | 63.1 ± 12.3 | < 0.0001 | 0.4015 |

| Muscle mass, kg, mean ± SD | 42.8 ± 8.2 | 42.4 ± 7.6 | 0.4376 | 44.6 ± 8.8 | 43.1 ± 9.5 | 0.0989 | 0.5402 |

| Lean body mass, kg, mean ± SD | 45.3 ± 8.6 | 44.9 ± 8.0 | 0.4543 | 47.2 ± 9.2 | 45.7 ± 9.9 | 0.1363 | 0.6074 |

| Body fat, kg, mean ± SD | 14.3 ± 6.6 | 13.5 ± 6.6 | 0.1630 | 18.4 ± 6.9 | 17.4 ± 6.2 | 0.1255 | 0.9494 |

| Skeletal muscle mass | 24.7 ± 5.2 | 24.4 ± 4.9 | 0.3361 | 25.9 ± 5.7 | 25.0 ± 6.2 | 0.1338 | 0.7156 |

| Skeletal muscle index | 6.91 ± 1.14 | 6.81 ± 0.95 | 0.4287 | 7.24 ± 1.13 | 6.93 ± 1.19 | 0.0753 | 0.4861 |

| CONUT score | 4.1 ± 2.5 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 0.4145 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | 0.7999 | 0.6870 |

An exploratory analysis was conducted to evaluate the incidence of SSIs based on the tumor location in the colon and rectum by combining both groups. The incidences of SSIs were 5.6% (1/18) and 35.3% (6/17) in patients with colon cancer (n = 18) and rectal cancer (n = 17), respectively. Although a higher incidence was observed in patients with rectal cancer, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 6). Further analysis based on anatomical subdivisions [colon plus rectosigmoid colon (n = 23) vs upper and lower rectum (n = 12)] revealed SSI rates of 8.7% (2/23) and 41.7% (5/12), respectively. The incidence rate was significantly higher in the upper and lower rectal cancer subgroups (Table 6).

| SSI | |

| RS-Rb (n = 17) | 6 (35.3) |

| C-S (n = 18) | 1 (5.6) |

| Odds ratio | 9.273 |

| 95%CI | 0.979-87.870 |

| P value | 0.0522 |

| Ra-Rb (n = 12) | 5 (41.7) |

| C-RS (n = 23) | 2 (8.7) |

| Odds ratio | 7.498 |

| 95%CI | 1.180-47.660 |

| P value | 0.0328 |

No adverse events related to RK5, including clinically significant laboratory abnormalities, were observed. The proportion of patients who underwent diverting stoma creation was 23.5% (4/17) in the nutritional intervention group and 33.3% (6/18) in the control group. Among patients without a stoma, the mean daily number of bowel movements during the study period was 1.27 ± 0.95 in the intervention group and 1.37 ± 1.23 in the control group, with no statistically significant difference between the groups. The incidence of diarrhea among patients without stomas was 23.1% (3/13) in the intervention group and 33.3% (4/12) in the control group, which was not significantly different.

In patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery, perioperative nutritional intervention using RK5 resulted in a higher achievement rate of target energy intake compared to standard hospital meals and was associated with a trend toward a reduced incidence of SSIs. Among gastrointestinal surgeries, colorectal cancer has the highest postoperative SSI incidence among elective abdominal procedures[4]. A cohort analysis of 15 years of SSI surveillance in Spain revealed a significant reduction in SSI rates across three surveillance periods: From 19.6% to 7.6% for colon surgery and from 20.6% to 12.8% for rectal surgery[12]. This decrease has been attributed to adherence to six key perioperative preventive measures: Preoperative intravenous antibiotic administration immediately before surgery, oral antibiotic administration on the day before surgery, mechanical bowel preparation, laparoscopy, maintaining normothermia, and the application of a dual-ring wound protector. The same surveillance report indicated a clear inverse relationship between the number of measures implemented and SSI incidence: The rate decreased from 16.71% in patients with no measures adhered to and 6.23% in those where all six measures were implemented[13]. In the univariate analysis, all measures except normothermia were associated with a decrease in overall SSI. Multivariate analysis showed that laparoscopy, oral antibiotic administration, and wound protectors decreased overall colorectal SSI[13]. Although SSI rates vary depending on the surgical procedure and the degree of invasiveness, the incidence remains relatively high after rectal surgery, even with full adherence to preventive measures. Moreover, the incidence of SSIs after colon surgery is not negligible. These findings suggest that additional strategies are required to prevent SSIs.

In a 2-year observational study of general surgical patients, poor nutritional status assessed by the nutritional risk screening 2002, BMI, and serum albumin levels was associated with adverse outcomes, including postoperative infections, delayed wound healing, prolonged hospital stays, increased rates of readmission, and higher 30-day mortality[14]. Malnutrition has been reported to exacerbate inflammatory responses, delay wound healing, and impair immune function[15]. In patients with colorectal cancer, frailty is commonly observed due to tumor-induced hypermetabolism, gastrointestinal symptoms leading to malnutrition, and systemic inflammation[16]. Frailty in colorectal cancer patients has been identified as a significant modifier of postoperative outcomes, including postoperative complications and overall survival[17,18], and is also associated with a significantly higher incidence of SSIs[19]. Although several meta-analyses have evaluated the impact of oral nutritional supplements and enteral nutrition on postoperative outcomes in gastrointestinal surgery[20], their effectiveness in preventing postoperative infections remains inconclusive, partly due to variations in postoperative care protocols among the studies.

In the present study, the percentage of patients who achieved their target energy intake was significantly higher in the nutritional intervention group receiving RK5 supplementation. Notably, supplemental intake of RK5 during the two days prior to surgery was associated with a trend toward reduce incidence of SSIs. Although postoperative nutritional supplementation was not directly related to SSI incidence, the ability to complete dietary intake in patients without forced interruption of meals may have contributed to favorable outcomes. However, the extent to which nutritional supplementation is required to achieve clinically significant benefits remains unclear. Nonetheless, the significant improvement in the attainment of the target energy intake in the intervention group is considered an important finding.

High levels of inflammation are known to contribute to worse postoperative outcomes[21], and inflammation may also impair intestinal immunity. RK5 contains heat-killed lactic acid bacteria. These heat-killed bacterial components demonstrated gastric protective effects in acute gastric injury models, likely by reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines[22]. Additionally, the intake of heat-killed lactic acid bacteria by healthy individuals has been associated with increased immunoglobulin M levels, suggesting a potential enhancement in immune function[23].

Furthermore, perioperative hyperglycemia significantly increases the risk of postoperative complications, particularly infectious complications, necessitating appropriate glycemic control during the perioperative period. Palatinose, a carbohydrate included in RK5, not only causes a gradual increase in postprandial blood glucose and insulin levels[24,25] but also suppresses the glycemic response to concurrently ingested carbohydrates[26,27]. Guar gum hydrolysate, another component of RK5, has similarly been reported to reduce postprandial glucose spikes[28]. Compared with conventional enteral nutrition formulas composed primarily of rapidly digestible carbohydrates, RK5, when consumed in equal caloric amounts, reduces postprandial blood glucose elevation in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance[29]. These characteristics may have contributed to the observed reduction in the SSI incidence in the RK5 intervention group.

Among the inflammatory markers measured at admission, on the day of surgery, and at the end of the study, TNF-α levels significantly increased from the day of surgery to the end of the study in both groups. This increase was likely attributable to surgical stress, and no significant difference in the magnitude of the increase was observed between the groups (Table 5). Similarly, the C-reactive protein levels increased postoperatively in both groups, with no significant intergroup differences in the extent of elevation. These findings may be partly explained by the fact that all the enrolled patients had inflammatory marker levels within the normal range at the time of admission. Although exploratory in nature, our analysis demonstrated a higher incidence of SSIs following rectal surgery than after colon surgery among the study participants. This finding is consistent with that of previous studies[12]. The factors influencing SSI development differ between colon and rectal surgeries. For colon surgery, the risk factors include lack of oral antibiotic prophylaxis and stoma closure, whereas for rectal surgery, preoperative steroid use, preoperative radiation therapy, and stoma creation have been identified as major risk factors[30].

In another study focusing specifically on organ/space SSIs, male sex and stoma formation were reported as risk factors in colon surgery, whereas the laparoscopic approach and oral antibiotic use were associated with a reduced risk. In contrast, male sex and prolonged operative time were significant risk factors for rectal surgery and oral antibiotic administration was the only protective factor identified[31]. The stronger protective effects of oral antibiotics during rectal surgery may reflect a higher bacterial load in the rectum. Furthermore, rectal surgeries often require extensive procedures, including multivisceral resections, leading to longer operative times and greater blood loss, which are recognized as contributors to an increased risk of SSI. This study had some limitations. First, the sample size is small. Second, the investigation was conducted at a single institution, which may have introduced a selection bias and limited the generalizability of the findings. Large-scale multicenter controlled trials are warranted to validate these results. Third, important factors such as health-related behaviors were not assessed. Future research should incorporate these elements into its study design.

In patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery, perioperative nutritional supplementation with RK5 was associated with a trend toward a reduced incidence of SSIs compared to standard hospital meals. Therefore, RK5 may be considered a viable option for perioperative nutritional support.

We sincerely thank all the individuals who participated in this study.

| 1. | Costa ACD, Santa-Cruz F, Torres AV, Caldas EAL, Mazzota A, Kreimer F, Ferraz ÁAB. Surgical site infection in resections of digestive system tumours. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2024;37:e1817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hou Y, Collinsworth A, Hasa F, Griffin L. Incidence and impact of surgical site complications on length of stay and cost of care for patients undergoing open procedures. Surg Open Sci. 2023;14:31-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ohge H, Mayumi T, Haji S, Kitagawa Y, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Mizuguchi T, Mohri Y, Sakamoto F, Shimizu J, Suzuki K, Uchino M, Yamashita C, Yoshida M, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Kusachi S; Committee for Gastroenterological Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, the Japan Society for Surgical Infection. The Japan Society for Surgical Infection: guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of gastroenterological surgical site infection, 2018. Surg Today. 2021;51:1-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance. Japan nosocomial infections surveillance. [cited 3 May 2025]. Available from: https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/english/report/index.html. |

| 5. | Fukuda Y, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Nishikawa K, Maeda S, Haraguchi N, Miyake M, Hama N, Miyamoto A, Ikeda M, Nakamori S, Sekimoto M, Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T. Prevalence of Malnutrition Among Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Gastrectomy and Optimal Preoperative Nutritional Support for Preventing Surgical Site Infections. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S778-S785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kwag SJ, Kim JG, Kang WK, Lee JK, Oh ST. The nutritional risk is a independent factor for postoperative morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;86:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Braga M, Gianotti L, Nespoli L, Radaelli G, Di Carlo V. Nutritional approach in malnourished surgical patients: a prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2002;137:174-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Noort HHJ, Ettema RGA, Vermeulen H, Huisman-de Waal G; Basic Care Revisited Group (BCR). Outpatient preoperative oral nutritional support for undernourished surgical patients: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:7-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fujitani K, Tsujinaka T, Fujita J, Miyashiro I, Imamura H, Kimura Y, Kobayashi K, Kurokawa Y, Shimokawa T, Furukawa H; Osaka Gastrointestinal Cancer Chemotherapy Study Group. Prospective randomized trial of preoperative enteral immunonutrition followed by elective total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ogilvie J Jr, Mittal R, Sangster W, Parker J, Lim K, Kyriakakis R, Luchtefeld M. Preoperative Immuno-Nutrition and Complications After Colorectal Surgery: Results of a 2-Year Prospective Study. J Surg Res. 2023;289:182-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control. Surgical Site Infection Surveillance Department. [cited 13 May 2025]. Available from: http://www.kankyokansen.org/modules/iinkai/index.php?content_id=5. |

| 12. | Badia JM, Almendral A, Flores-Yelamos M, Gomila-Grange A, Parés D, Pascual M, Fraccalvieri D, Abad-Torrent A, Solís-Peña A, López L, Piriz M, Hernández M, Limón E, Pujol M; VINCat Colorectal Program. Reduction of surgical site infection rates in elective colorectal surgery by means of a nationwide interventional surveillance programme. A cohort study. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2025;43 Suppl 1:S28-S36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Badia JM, Arroyo-Garcia N, Vázquez A, Almendral A, Gomila-Grange A, Fraccalvieri D, Parés D, Abad-Torrent A, Pascual M, Solís-Peña A, Puig-Asensio M, Pera M, Gudiol F, Limón E, Pujol M; Members of the VINCat Colorectal Surveillance Team; VINCat Program*. Leveraging a nationwide infection surveillance program to implement a colorectal surgical site infection reduction bundle: a pragmatic, prospective, and multicenter cohort study. Int J Surg. 2023;109:737-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Keerio RB, Ali M, Shah KA, Iqbal A, Mehmood A, Iqbal S. Evaluating the Impact of Preoperative Nutritional Status on Surgical Outcomes and Public Health Implications in General Surgery Patients. Cureus. 2024;16:e76633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alwarawrah Y, Kiernan K, MacIver NJ. Changes in Nutritional Status Impact Immune Cell Metabolism and Function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Virizuela JA, Camblor-Álvarez M, Luengo-Pérez LM, Grande E, Álvarez-Hernández J, Sendrós-Madroño MJ, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Cervera-Peris M, Ocón-Bretón MJ. Nutritional support and parenteral nutrition in cancer patients: an expert consensus report. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20:619-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abdelfatah E, Ramos-Santillan V, Cherkassky L, Cianchetti K, Mann G. High Risk, High Reward: Frailty in Colorectal Cancer Surgery is Associated with Worse Postoperative Outcomes but Equivalent Long-Term Oncologic Outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:2035-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Han J, Zhang Q, Lan J, Yu F, Liu J. Frailty worsens long-term survival in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1326292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang W, Ye Y. Effect of preoperative frailty on postoperative infectious complications and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: a propensity score matching study. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sowerbutts AM, Burden S, Sremanakova J, French C, Knight SR, Harrison EM. Preoperative nutrition therapy in people undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;4:CD008879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | West NR, McCuaig S, Franchini F, Powrie F. Emerging cytokine networks in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:615-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jeon DB, Shin HG, Lee BW, Jeong SH, Kim JH, Ha JH, Park JY, Kwon HJ, Kim WJ, Ryu YB, Lee IC. Effect of heat-killed Enterococcus faecalis EF-2001 on ethanol-induced acute gastric injury in mice: Protective effect of EF-2001 on acute gastric ulcer. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2020;39:721-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takahashi K, Nakagawasai O, Uwabu M, Iwasa M, Iwasa H, Tsuji M, Takeda H, Tadano T. Immunological Benefits of Enterococcus faecalis 2001 in Healthy Volunteers. Jpn Pharmaco Ther. 2021;49:913-916. |

| 24. | Holub I, Gostner A, Theis S, Nosek L, Kudlich T, Melcher R, Scheppach W. Novel findings on the metabolic effects of the low glycaemic carbohydrate isomaltulose (Palatinose). Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1730-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Maeda A, Miyagawa J, Miuchi M, Nagai E, Konishi K, Matsuo T, Tokuda M, Kusunoki Y, Ochi H, Murai K, Katsuno T, Hamaguchi T, Harano Y, Namba M. Effects of the naturally-occurring disaccharides, palatinose and sucrose, on incretin secretion in healthy non-obese subjects. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kashimura J, Nagai Y. Inhibitory effect of palatinose on glucose absorption in everted rat gut. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2007;53:87-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kashimura J, Nagai Y, Goda T. Inhibitory action of palatinose and its hydrogenated derivatives on the hydrolysis of alpha-glucosylsaccharides in the small intestine. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:5892-5895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tokunaga M, Yasukawa Z, Ozeki M, Saito J. Effect of partially hydrolyzed guar gum on postprandial hyperglycemia: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover-study. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:85-91. |

| 29. | Kato M, Kashimura J, Inada Y, Sakazaki M, Nagai S, Kato N. Effects of a Concentrated Liquid Nutrient Containing Palatinose and Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum on Blood Glucose Trends for Glucose Intolerant - Randomized Crossover Controlled Trial. Jpn Pharmaco Ther. 2023;51:757-763. |

| 30. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: results of prospective surveillance. Ann Surg. 2006;244:758-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gomila A, Carratalà J, Camprubí D, Shaw E, Badia JM, Cruz A, Aguilar F, Nicolás C, Marrón A, Mora L, Perez R, Martin L, Vázquez R, Lopez AF, Limón E, Gudiol F, Pujol M; VINCat colon surgery group. Risk factors and outcomes of organ-space surgical site infections after elective colon and rectal surgery. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/