INTRODUCTION

The spleen plays a vital role in the immune system, facilitating the clearance of encapsulated bacteria and supporting hematologic and immunologic function[1]. Despite this, the impact of splenectomy during distal pancreatectomy has historically been underappreciated. Traditionally, the main argument for performing a distal pancreatectomy with concurrent splenectomy was mainly due to concerns of increased operative complexity, and oncologic outcomes when peri-splenic lymphadenectomy is necessary for pathological staging[2]. However, in the past decades, several studies have demonstrated the post-splenectomy short- and long-term detrimental effects[3-5]. In the short term, spleen preservation has been associated with less intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and lower rates of abscess formation, portal vein thrombosis, new-onset diabetes, and clinically significant pancreatic fistulas[4,6].

Regarding long-term post-splenectomy outcomes, the risks of complications have been well studied, and this includes an increased risk of post-operative infections, such as an increased risk of developing pyogenic liver abscess and, more importantly, overwhelming post-splenectomy infection, which is calculated to be around 0.1%-8.5%[6-8]. Other studies have found that splenectomy patients have an increased risk of death from pneumonia and ischemic heart disease, even more than 10 years after splenectomy[5,9]. Additionally, there is an increased risk for thromboembolic events, especially pulmonary embolism, and an increased risk of overall cancer, as well as certain site-specific cancers[10,11]. Hence, the decision to do a splenectomy shouldn’t be taken lightly, as short and long-term outcomes are significant. This mini-review discusses the rationale, indications, and technical considerations for minimally invasive spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy (SPDP) in patients with body and distal pancreatic disease.

LITERATURE SEARCH

This narrative review was conducted to synthesize current evidence on the short- and long-term outcomes of splenectomy vs SPDP using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar to identify relevant English-language articles including the must up to date supporting evidence. Key search terms included: “spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy”, “splenectomy”, “minimally invasive pancreatic surgery”, “neuroendocrine tumors”, “solid pseudopapillary neoplasm”, “intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm”, and “post-splenectomy complications”. Additional landmark and guideline documents were manually added, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines for pancreatic neoplasms. Preference was given to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, multicenter studies, and large retrospective cohorts reporting on oncologic safety, perioperative outcomes, and long-term risks related to splenectomy or splenic preservation. References were screened for relevance and impact on clinical practice. Studies focusing on pediatric populations or exclusively open techniques without minimally invasive comparison were excluded.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING SPLEEN PRESERVATION

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Current guidelines, including the NCCN and ESMO guidelines regarding pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas and spleen preservation, are clear, and spleen preservation is generally not indicated[12,13]. The reasoning behind this recommendation is that obtaining negative margins and an appropriate lymph node harvest is imperative. Additionally, in the setting of high-grade malignancies or when oncological principles dictate, splenectomy may be unavoidable due to tumor invasion or the need for lymphatic staging. However, recent studies have evaluated the possibility of preserving the spleen in an oncologic intervention. In a matched cohort study for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma of the body, SPDP showed comparable oncologic outcomes to distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy (DPS) and was associated with fewer complications, shorter hospital length-of-stay, and similar survival rates[14]. In a multicenter retrospective study and meta-analysis, spleen preservation during total or distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer was associated with significantly prolonged survival, without compromising oncologic or surgical outcomes, suggesting that splenectomy may be an independent risk factor for reduced overall survival, particularly in total pancreatectomy cases[15]. Interestingly, the authors found no association with lesion size or nodal status. However, the retrospective design limits the strength of these findings. Unfortunately, there are no randomized controlled trials that support spleen preserving, and most guidelines recommend concurrent splenectomy. Additionally, both LEOPARD and DIPLOMA trials support minimally invasive approaches for distal pancreatic cancers including splenectomy as a curative-intent treatment, with better surgical outcomes and promising oncologic outcomes on DIPLOMA (non-inferiority trial), nevertheless, with a short median follow up (23.5 months)[16,17].

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are cystic pancreatic lesions with potential for malignancy. For high-risk or worrisome IPMNs of the body and tail of the pancreas, surgical intervention, typically via distal pancreatectomy, is often recommended. Traditionally, this procedure included splenectomy due to concerns about lymph node metastasis (LNM). However, recent evidence suggests that SPDP may be a viable alternative in select patients[18]. There is emerging evidence, including an international multicenter cohort study, showing that in patients without preoperative suspicion of malignancy, SPDP seemed oncologically safe and was associated with improved short-term outcomes compared with DPS. This international multicenter cohort study involving 700 patients compared outcomes between SPDP and DPS[19]. The study found that among patients without preoperative suspicion of malignancy, the rate of LNM was 4.3%. In this subgroup, SPDP was associated with improved short-term outcomes, including shorter operating times (median 180 minutes vs 226 minutes), reduced blood loss (100 mL vs 336 mL), and shorter hospital stays (5 days vs 8 days), compared to DPS[19]. No significant difference in overall survival was observed between the two groups after adjusting for prognostic factors. These findings suggest that SPDP can be oncologically safe and may offer better short-term outcomes for patients with IPMNs without preoperative indicators of malignancy. Preserving the spleen may also reduce the risk of postoperative infectious complications and preserve immune function[20]. It's important to note that the decision to preserve the spleen in IPMN should be individualized, considering factors such as the lesion's characteristics and the patient's overall health. Further research is warranted to confirm these findings and to refine surgical guidelines for IPMN management.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

As is the case for other types of tumors, for many years, distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) was routinely performed with splenectomy (DPS) due to oncologic, technical, and misjudged risk considerations[21]. Early expert guidelines and World Health Organization classifications treated even small, well-differentiated PNETs as potentially malignant, especially if > 2 cm or if nodes were positive[22]. An en-bloc splenectomy was thought necessary to clear lymph nodes at the splenic hilum, given nodal metastases rates of approximately 30% in non-functional PNETs and their impact on survival[23]. Accordingly, consensus recommendations defaulted to DPS for body/tail tumors to ensure adequate lymphadenectomy[24]. Technically, SPDP was historically reserved for clearly benign lesions (e.g., insulinomas) because it was considered more complex and risk-prone[20]. Surgeons favored the simplicity and safety of removing the spleen rather than attempting vessel preservation or Warshaw’s technique[25,26], which carried risks of hemorrhage, splenic infarction, or gastric varices. As a result, DPS became the standard for malignant or borderline PNETs in the 2000s[27]. Most recent consensus, such as the one from the United States PNET society, supports the utilization of SPDP as a feasible and oncologically sound surgical approach for patients with PNETs[28]. Evidence shows that SPDP results in similar perioperative outcomes—such as operative time, blood loss, and recovery—compared to DPS. Moreover, long-term oncologic outcomes such as overall survival and recurrence-free survival appear equivalent between SPDP and DPS, underscoring the oncologic safety of spleen preservation. Given the added immunologic and hematologic benefits of maintaining splenic function, SPDP should be actively considered for appropriately selected patients with PNET, particularly when spleen preservation is technically achievable without compromising oncologic principles.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) also known as Frantz tumor is a rare exocrine neoplasm, accounting for between 2%-3% of all pancreatic neoplasm, and carries a distinct presentation due to a low metastatic potential and with a 5-10 year overall survival > 95%[29,30] Generally, 90% of patients are female, and the age at diagnosis ranges between 20 to 30 years. The median size of the tumor is around 6 cm, ranging from 2 to 34 cm[30]. SPN tumors are usually described macroscopically as a round, well-demarcated lesion. Considering its predominantly local involvement, with rare cases of metastases, surgery is usually the definitive treatment with the objective of complete resection, and specifically for SPN of the body or distal pancreas, every attempt should be made to conserve the spleen.

Chronic pancreatitis

For benign diseases such as pancreatic cystic disease or chronic pancreatitis, Spleen preservation should be prioritized whenever feasible; however, specifically for chronic pancreatitis, the en-bloc distal pancreatic-spleen resection is mostly performed for technical reasons, as in clinical practice, spleen preservation might be extremely challenging due to inherent anatomic restrictions. If the spleen is preserved, there are several benefits, including less risk of insulin-dependent diabetes[31].

TECHNICAL RATIONAL

Although spleen preservation is particularly recommended in cases of benign pancreatic lesions and conditions with a favorable prognosis such as PNET (smaller than 2 cm), SPN (Frantz tumor), or IPMN, it has been a topic of long debate with current evidence shifting towards to spleen preservation. Historically, one of the primary arguments for performing a concomitant splenectomy is the risk of bleeding, either intra- or postoperatively, due to injuries to splenic vessels or the spleen. Nevertheless, pancreatic surgery has become significantly safer due to greater comprehension of pancreatic anatomy, optimal preoperative and intraoperative imaging, and improvements in both surgical techniques and numerous surgical devices used when performing either open or minimally invasive pancreatic surgery[32]. Sparing the spleen balances limited resection for benign tumors with safe surgical margins, while avoiding unnecessary node dissection.

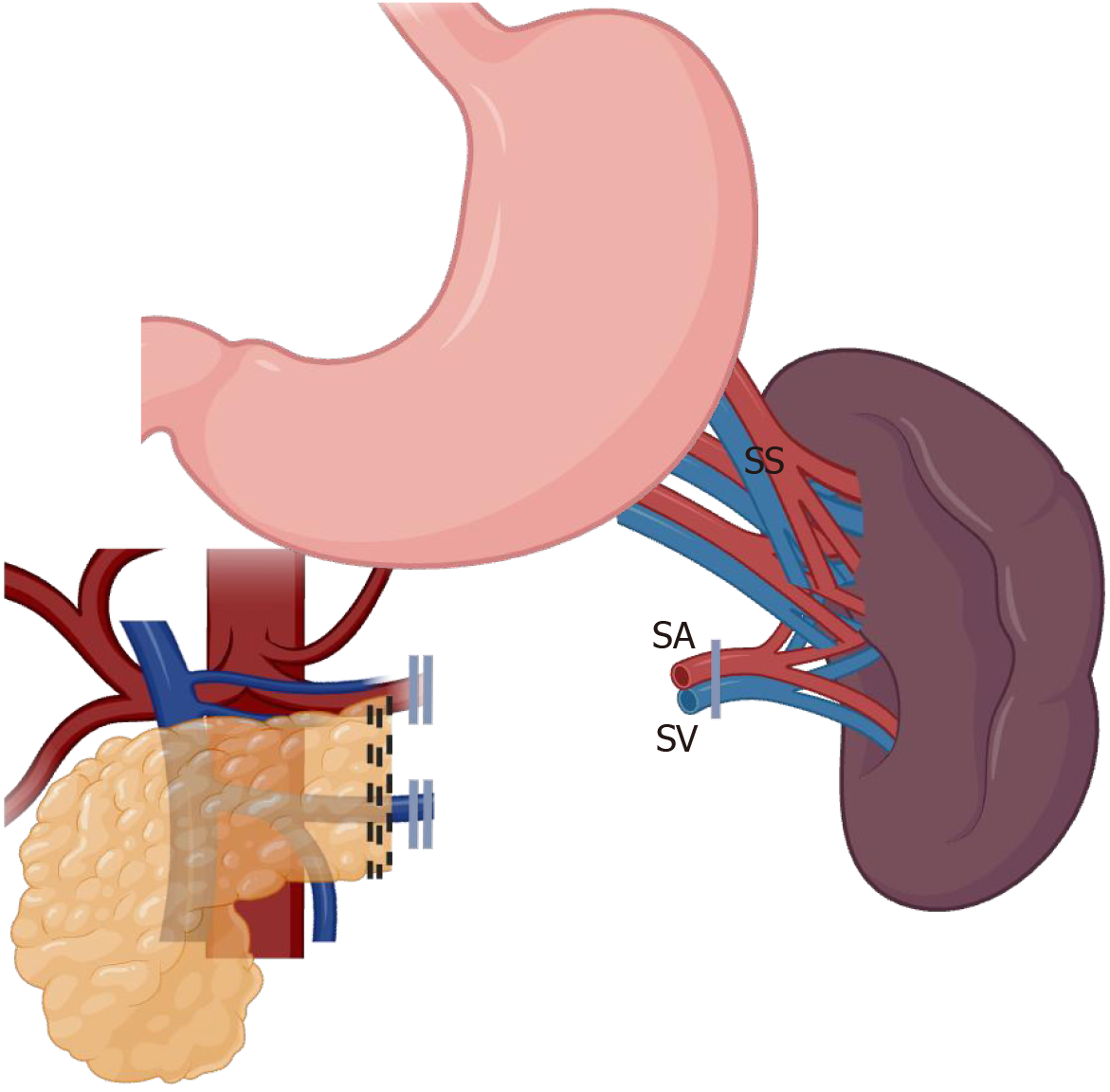

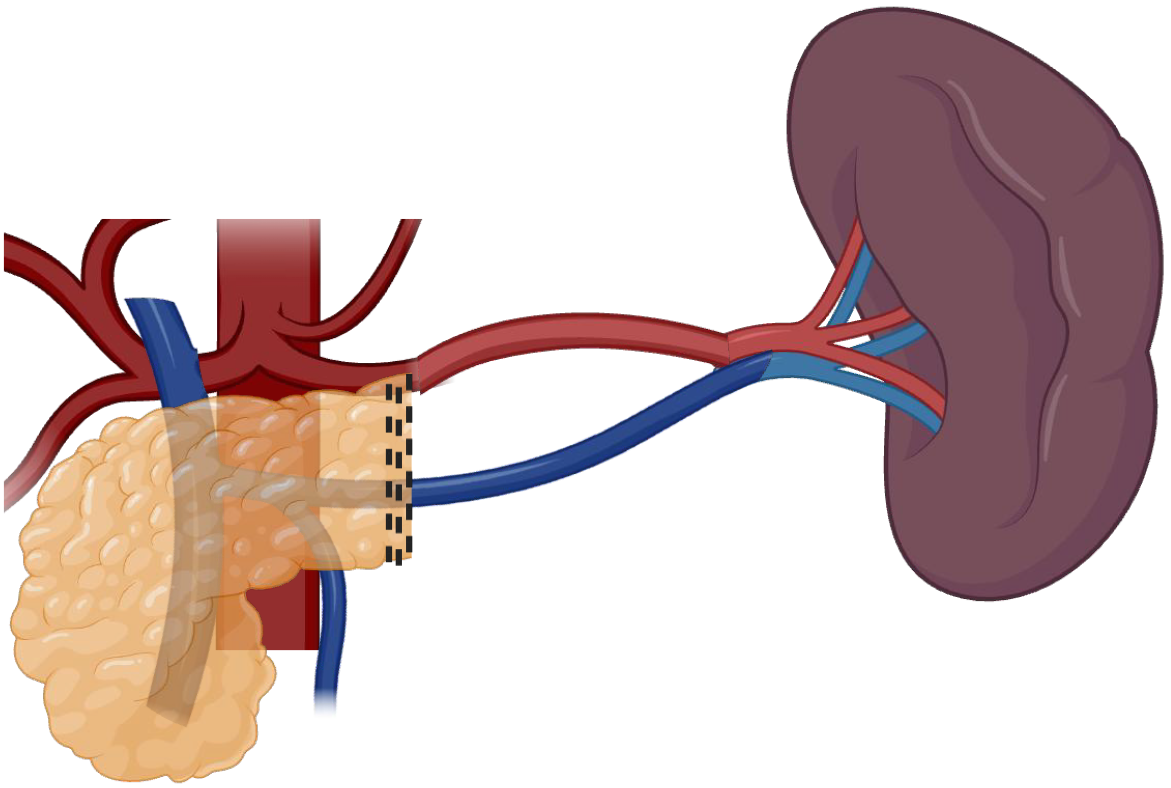

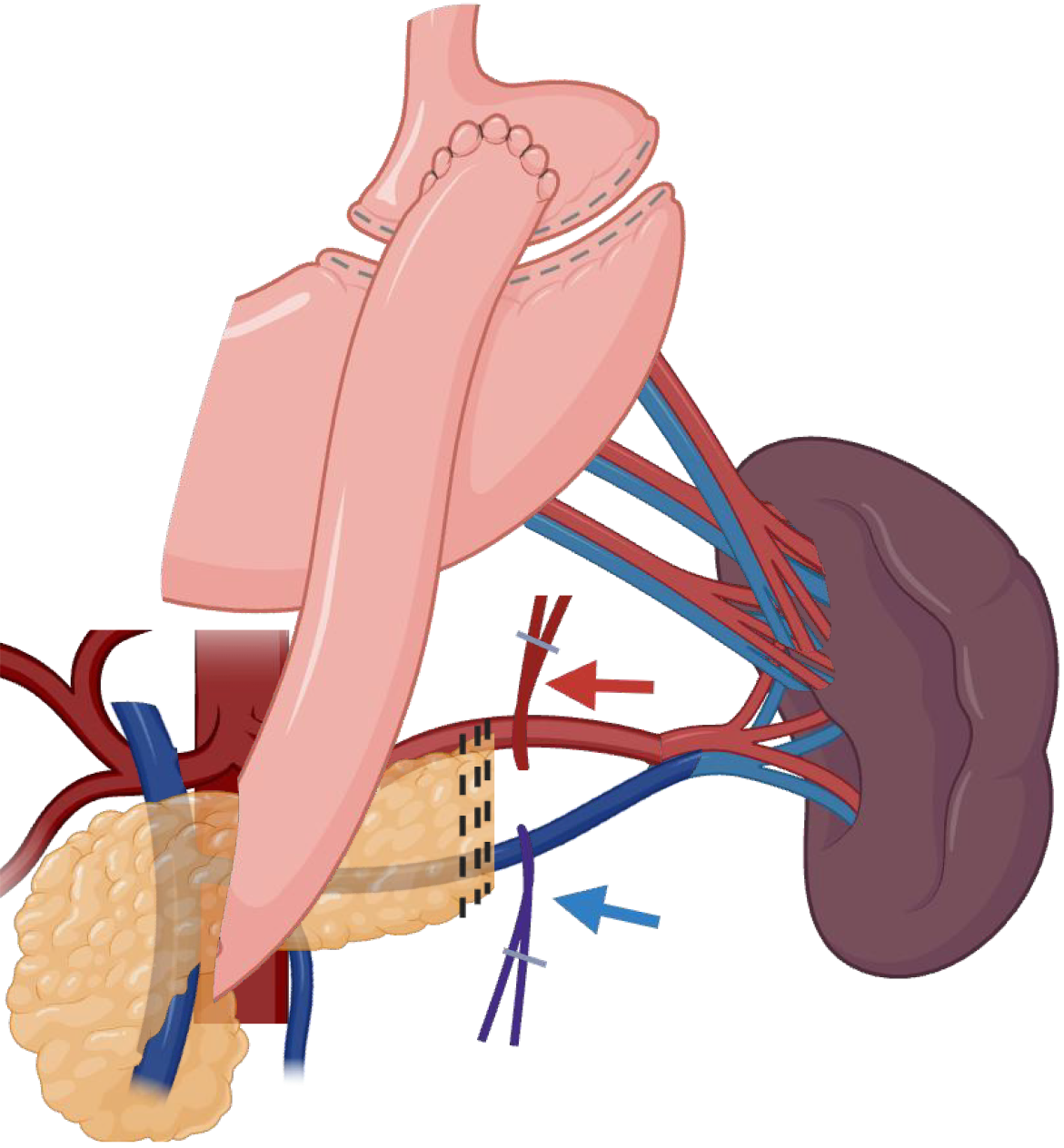

Two primary techniques have been described and widely disseminated for spleen preservation: (1) Warshaw technique: This method involves sacrificing the splenic artery and vein while preserving the short gastric and gastroepiploic vessels for splenic perfusion, as demonstrated in Figure 1. It is technically less complex but carries a risk of mid and long-term splenic congestion and occasionally infarction[25]; and (2) Kimura technique: This approach maintains the splenic artery and vein, ensuring optimal splenic blood flow. It is technically more demanding but minimizes the risk of infarction and preserves splenic function more effectively, as demonstrated in Figure 2. This is the preferred technique since it favors long-term physiological outcomes of the spleen[26].

Figure 1 Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with en bloc removal of splenic vein and artery, and short gastric vessels preservation (Warshaw technique)[25].

SV: Splenic vein; SA: Splenic artery; SS: Short gastric. Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

Figure 2 Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with splenic vein and artery sparing, and short gastric vessels removal (Kimura technique)[26].

Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

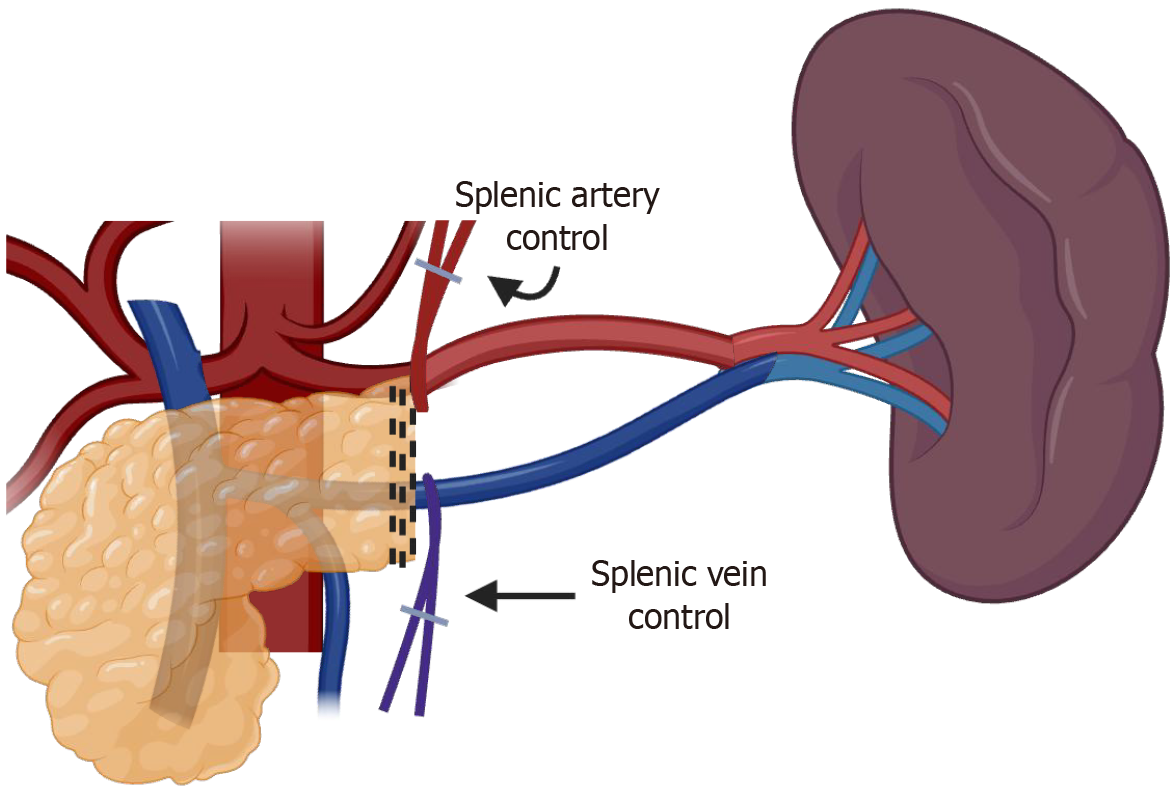

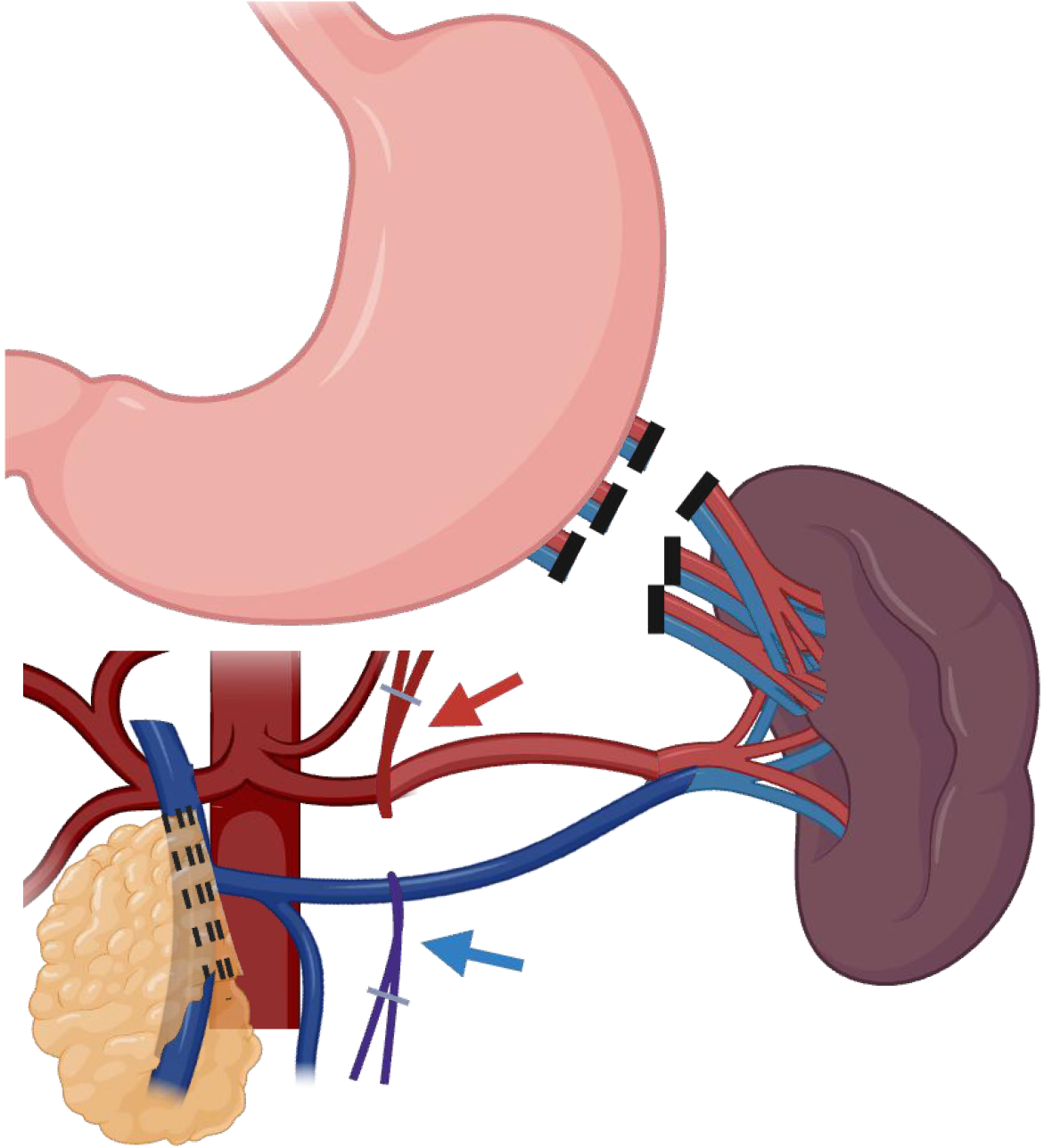

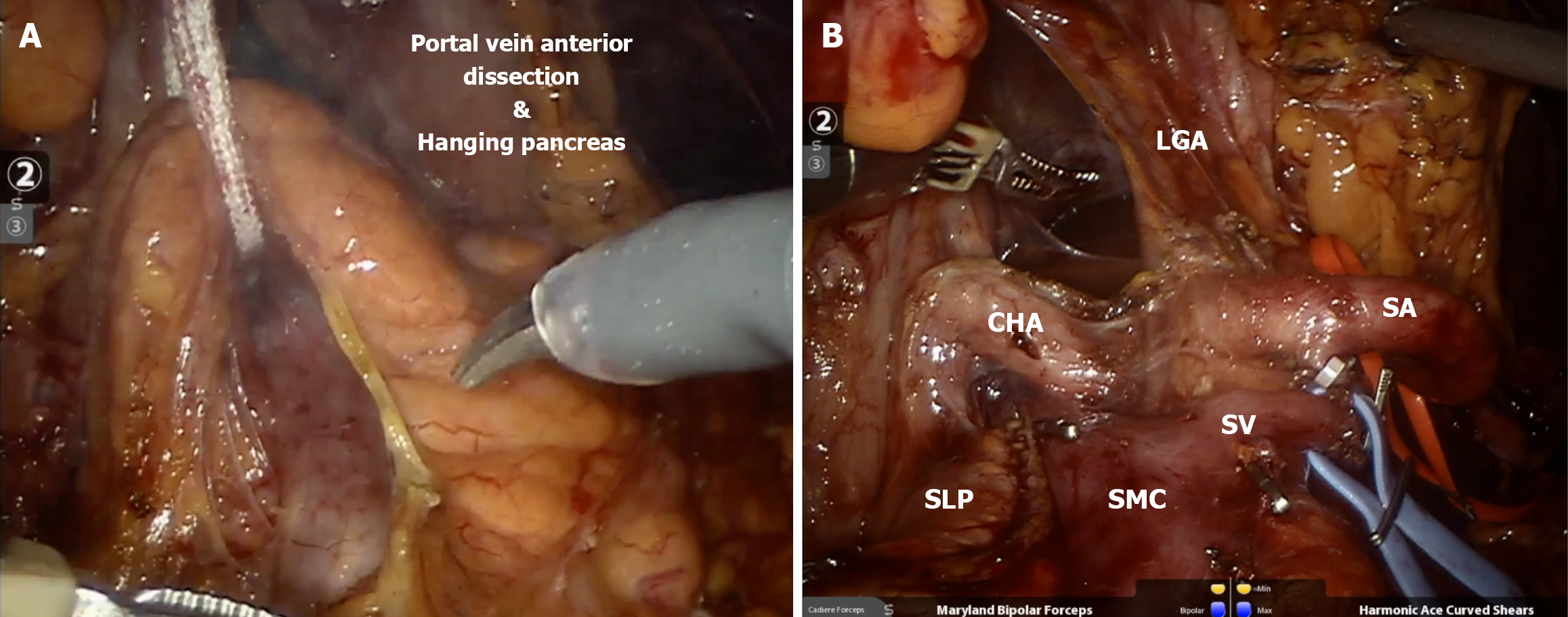

A stepwise approach is favored for either lesions in the neck/body or tail of the pancreas, with access to the retro-gastric cavity as a valuable first step to allow visualization of the pancreatic plateau as a guide for both anatomical references of the vessels and lesion identification. Afterward, upfront control of the splenic vessels combined with minimal mobilization of the pancreas should be a priority, as this is a core principle of splenic preservation, allowing bleeding control in case of unintended vessel injuries, as demonstrated in Figure 3. Moreover, upfront vascular control can also be used as a route to guide a safe dissection of the distal pancreas utilizing a medial-to-lateral approach until the most distal aspect of the pancreas into the splenic hilum is exposed. Figure 4 and Video 1 better exemplify the preferred approach for lesions close to the splenic-mesenteric confluence, and Figure 5 and Video 2 better exemplify the preferred approach for lesions close to the tail. Furthermore, for lesions located in the neck or body of the pancreas, early dissection and control of the superior mesenteric artery and portal vein can facilitate pancreatic mobilization. This maneuver enables the pancreas to be suspended or “hanging”, allowing for safer and more efficient identification and dissection of the splenic artery and vein before transection, as demonstrated in Figure 6 and Video 2. Finally, every patient undergoing a distal pancreatectomy should ideally be vaccinated in the preoperative setting, as there is always a risk of this procedure eventually ending with a splenectomy, especially in the setting of bleeding. Usual vaccinations include Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae B, and Meningococcus type C. Ideally, patients should receive pneumococcal vaccine from 4 to 6 weeks before elective splenectomy or initiation of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. If it is not possible, vaccination should be administered at least 2 weeks pre-operatively in elective cases or at least 2 weeks post-operatively in emergency cases[33].

Figure 3 Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with splenic vein and artery sparing using proximal control in case of bleeding.

Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

Figure 4 Example of upfront vessel control in lesions close to neck of the pancreas, using the splenic artery and splenic vein as route to dissection until the spleen, as also demonstrated in the Video 1.

Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

Figure 5 Example of upfront vessel control in lesions in tail of the pancreas, using the splenic artery and splenic vein as route to dissection until the spleen, especially for patients with previous Roux En Y gastric bypass as demonstrated in the Video 2.

Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

Figure 6 Robotic spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy.

A: Hanging of the neck of the pancreas for proximal dissection of splenic vessels; B: Final aspect of proximal transection of the pancreas with vessel loops on splenic artery (red) and vein (blue). LGA: Left gastric artery; CHA: Common hepatic artery; SLP: Staple Line of the pancreas; SMC: Splenomesenteric confluence; SV: Splenic Vein; SA: Splenic artery. Created in BioRender (Supplementary material).

DISCUSSION

Spleen preservation in distal pancreatectomies remains a controversial topic in pancreatic surgery. Historically, for benign pancreatic diseases, spleen removal was more related to technical challenges than to physiopathology. Moreover, Lee et al[34] demonstrated in a propensity-score matched analysis with 1248 Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomies in each group (spleen preservation vs splenectomy) that patients that underwent spleen-preservation had lower rates of postoperative infection (5.7% vs 9.7%, P < 0.001), postoperative pancreatic fistula (15.2% vs 19.1%, P = 0.003), and intrabdominal abscess (0.9% vs 2.8%, P < 0.001). Whether preserving splenic or short gastric vessels, early identification and control of the splenic artery and vein remains essential. This is not only to manage potential bleeding but also to serve as reliable anatomical landmarks for safe dissection through the splenic hilum as demonstrated in both Videos 1 and 2[34]. Whereas the shift from open to laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy arguably introduced greater technical challenges to spleen preservation, the advent of robotic platforms has perhaps helped mitigate many of these limitations. Despite lacking tactile feedback, robotic systems offer enhanced three-dimensional visualization, articulated instruments, and improved precision, which together facilitate meticulous dissection of the splenic vessels, optimizing exposure, particularly important in the event of inadvertent bleeding and suturing. These features make spleen preservation more achievable in selected cases. Nonetheless, regardless of the surgical approach, early and deliberate control of the splenic vessels remains a fundamental step for safe and effective SPDP.

CONCLUSION

SPDP should be considered in appropriately selected patients to minimize the risks associated with splenectomy. Advances in minimally invasive surgery have further enabled safer and more effective preservation techniques. However, high-quality prospective studies and randomized controlled trials comparing SPDP techniques (e.g., Warshaw vs Kimura) are needed to validate long-term oncologic safety and guide surgical decision-making. Clear guidelines stratified by tumor type and patient risk profile will further standardize practice. With continued refinement and broader evidence, SPDP may emerge as the preferred approach for many patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association; International Laparoscopic Liver Society; American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association; Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract; and American College of Surgeons.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Chisthi MM, MD, Professor, India S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Lei YY