Published online Aug 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i8.2592

Revised: June 19, 2024

Accepted: July 17, 2024

Published online: August 27, 2024

Processing time: 108 Days and 7.3 Hours

Medical treatment for Crohn’s disease (CD) has continuously improved, which has led to a decrease in surgical recurrence rates. Despite these advancements, 25% of patients will undergo repeat intestinal surgery. Recurrence of CD com

To compare the new anti-mesenteric side-to-side delta-shaped stapled anasto

This retrospective study included CD patients who underwent ileo-ileal or ileo-colic anastomosis between January 2020 and December 2023. The DSA technique employed a stapler to maintain the concept of anti-mesentery side-to-side ana

The study included 175 patients, including 92 in the DSA group and 83 in the CSA group. The two groups were similar in baseline characteristics, preoperative medical treatment, and operative findings except for the Montreal classification location. The 30-days postoperative complication rate was signi

The DSA technique was feasible and showed comparable postoperative outcomes with lower short-term complications compared with the CSA technique. Further studies on CD recurrence and long-term complications are warranted.

Core Tip: This study introduced a new anti-mesenteric side-to-side delta-shaped stapled anastomosis (DSA) technique employed to maintain the concept of anti-mesentery anastomosis by performing a 90° vertical closure of the open window. The DSA technique avoids pouch formation at the corner and creates a delta-shaped anastomosis within the intestinal lumen. Patients with Crohn’s disease who underwent intestinal surgery using the DSA technique had a significantly shorter hospital stay and a lower rate of postoperative complication compared with those who underwent conventional side-to-side anasto

- Citation: Lee JL, Yoon YS, Lee HG, Kim YI, Kim MH, Kim CW, Park IJ, Lim SB, Yu CS. New anti-mesenteric delta-shaped stapled anastomosis: Technical report with short-term postoperative outcomes in patients with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(8): 2592-2601

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i8/2592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i8.2592

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the gastrointestinal tract and is a major type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1]. Over the past two decades, treatment for CD has continuously improved, and as a result the surgical recurrence rate has decreased[2]. Despite pharmaceutical advancements, approximately 60%-80% of patients with CD will require major intestinal surgery during their lifetime. Among these patients, 25% will undergo repeat intestinal surgery[3,4].

Most recurrences after intestinal surgery for CD occur on the mesentery side of the bowel and proximal to the anastomosis[5]. This trend suggests that the actual surgery may play a role in the anastomosis site recurrence and that fecal stasis could contribute to this risk particularly in stapled side-to-side anastomosis. Despite the unknown impact of anastomotic configuration on recurrence, an anti-mesenteric hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis (Kono-S anastomosis) technique was developed to prevent postoperative recurrence[5,6]. The Kono-S anastomosis, introduced in 2011, is a novel technique designed specifically for CD bowel anastomosis[7]. It was shown to be superior to other anastomotic techniques in preventing clinical and endoscopic recurrence of postoperative CD[5].

Although Kono-S anastomosis has demonstrated good long-term results, hand-sewing results in a longer operation time, with a median time ranging from 157-215 minutes[5,7]. Due to this disadvantage, newer techniques, such as stapled Kono-S anastomosis, have recently been introduced[8,9]. These methods are generally more efficient as they reduce the operation time for anastomosis construction. Additionally, stapled anastomosis may be superior to hand-sewn anastomosis in terms of minimizing the risk of anastomotic leaks and recurrence of CD.

To address the need for a faster procedure while maintaining the principles of Kono-S anastomosis, we modified the conventional stapled functional end-to-end anastomosis (CSA) by incorporating a 90° vertical closure of the open window. This novel anastomotic technique, referred to as anti-mesenteric side-to-side delta-shaped stapled anastomosis (DSA), offers potential benefits such as wider anastomotic lumen and improved mesenteric alignment at the center of the second staple line. This study sought to describe the technical aspects and determine the potential advantages of DSA. In addition, we compared the short-term postoperative outcomes of the DSA technique with the CSA technique.

This retrospective study evaluated patients who underwent intestinal surgery for CD at the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea between January 2020 and December 2023. The study included patients who had undergone small bowel resection and anastomosis, ileocecal resection, or right colectomy. Exclusion criteria included patients who had undergone only strictureplasty, stoma closure or formation, combined left colon or rectal surgery, upper gastrointestinal surgery, three or more bowel resections and anastomoses, or those with combined malignancy.

Medical records of the included patients were reviewed for various factors, including demographic characteristics (age at diagnosis and operation, sex, body mass index at operation, family history, and history of smoking), preoperative disease characteristics, such as the Montreal classifications and medical treatments immediately preceding surgery (immunomodulators, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha, corticosteroids, and combination therapy), operative indications (stricture or obstruction, fistula or abscess, perforation, and bleeding), emergency operation status, surgical approach (open or laparoscopic), anastomotic technique (DSA or CSA), types of operations, number of anastomoses, hospital stay after surgery, operation time, intra-abdominal blood loss, transfusion after surgery, postoperative complications within 30 days post-operation, including infectious (wound, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, and other infection) and non-infectious (ileus, bleeding, and other complications) outcomes, and short-term surgical recurrence of CD. The study cohort was divided into two groups (DSA and CSA) based on the anastomotic method used.

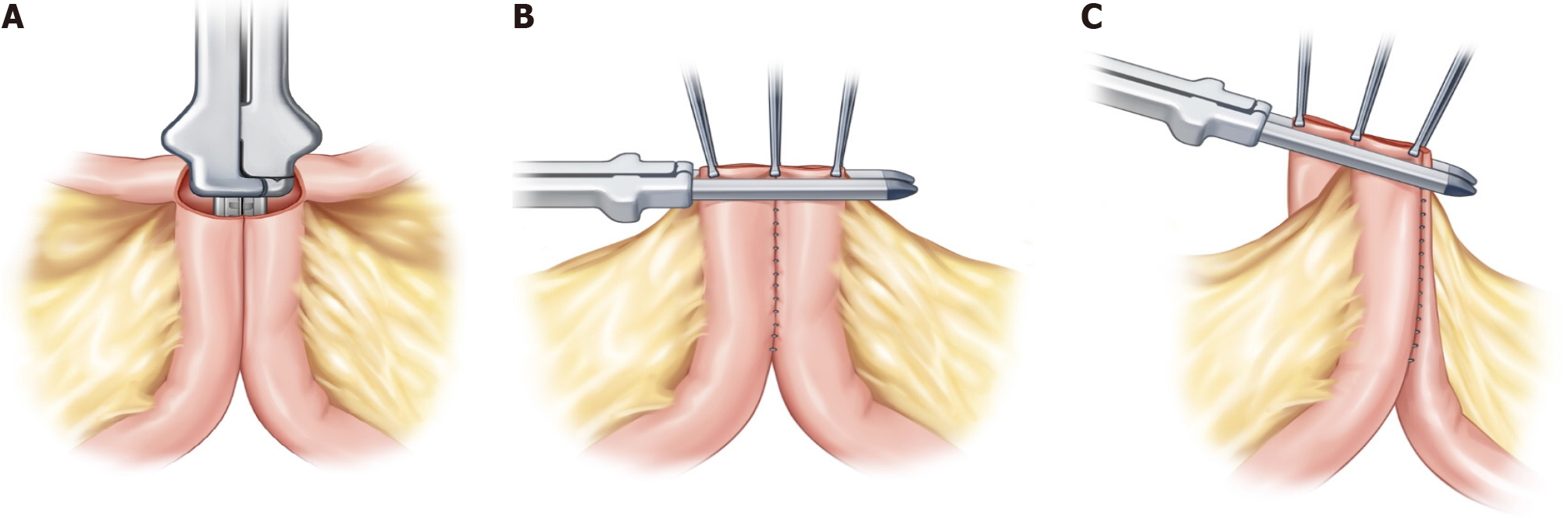

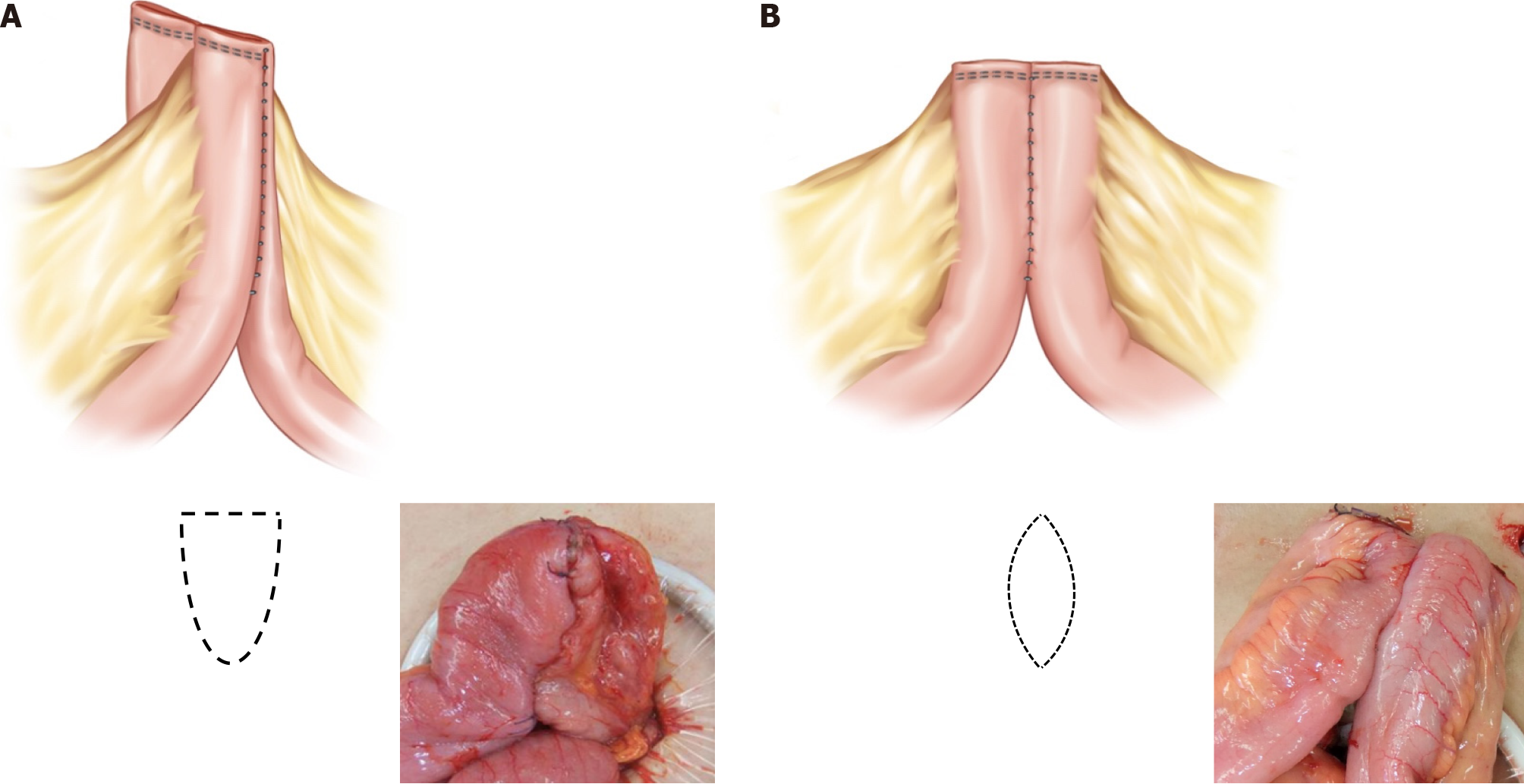

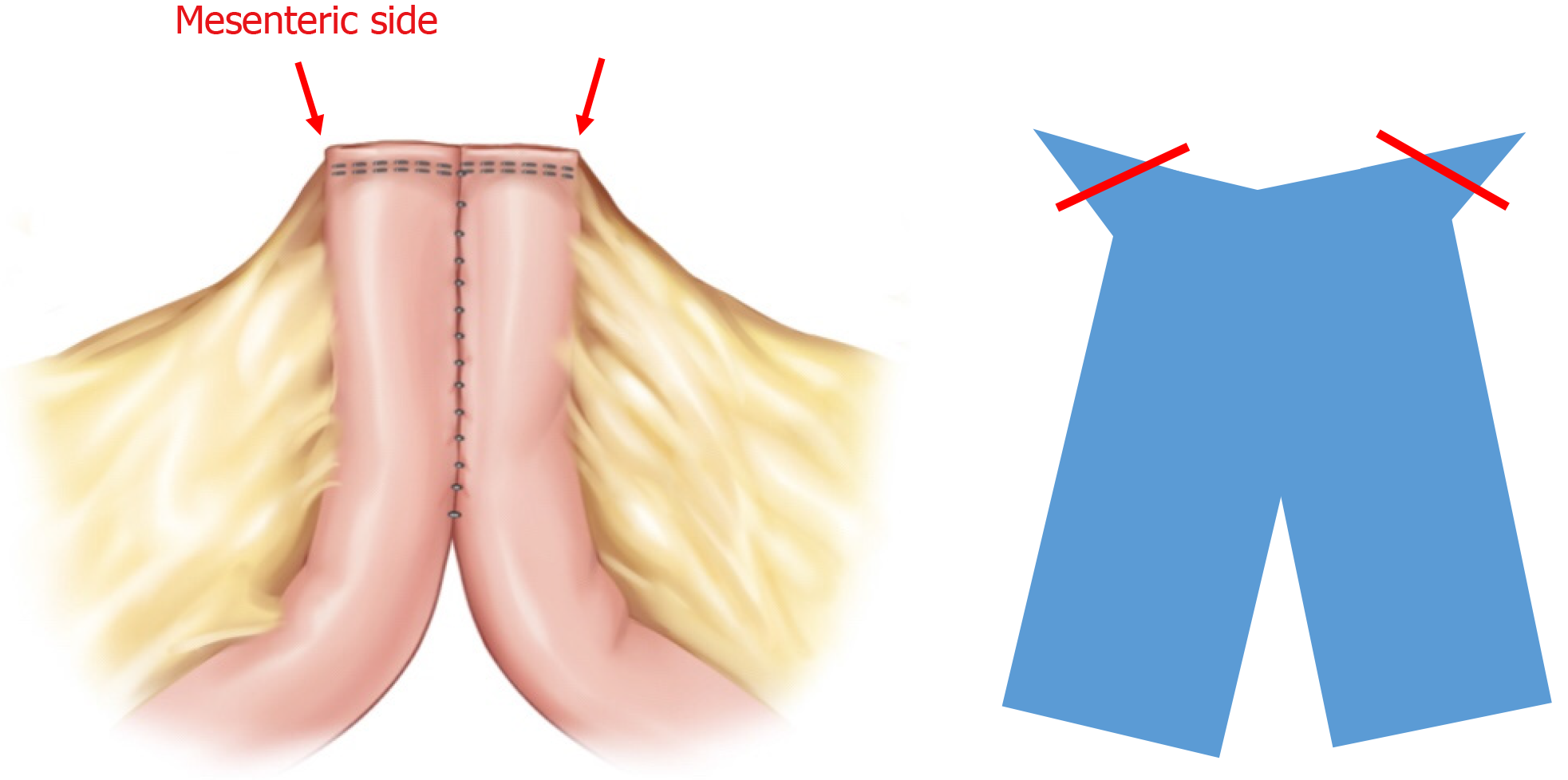

After preparing the mesentery side of the intestine for excision, small anti-mesenteric incisions were made on both the proximal and distal bowels. A linear stapler was then inserted into the small incision for the anastomosis (Figure 1A). In the CSA technique, the opened window is typically closed transversely (Figure 1B). In contrast, the DSA technique uses a vertical closure of the open window with a linear stapler (Figure 1C). This method results in the anastomosis being positioned exactly 90° outward from the direction of the mesentery, causing the open window to be pushed into the mesentery. The opened mesentery was subsequently closed, and reinforcement sutures were applied to prevent the distal part of the functional end-to-end anastomosis from forming a pouch. Upon observing the anastomosis within the intestinal lumen, it appears delta shaped (Figure 2A), as opposed to the ovoid shape of existing functional end-to-end anastomosis (Figure 2B). All surgeries in this study were performed by three experienced IBD surgeons who had conducted more than 200 IBD surgeries.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (Registration No. 2024-0322). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a retrospective study, informed consent was waived for the study subjects.

Postoperative complications were defined as grade II or higher on the Clavien-Dindo classification within the first 30 days after surgery. Complications were categorized as infectious and non-infectious. Infectious complications included wound infections, intra-abdominal abscess determined by a notable change in drainage or abdominopelvic computed tomography, anastomotic leaks confirmed through clinical evaluation and requiring surgical interventions, and other site infections including Clostridium difficile infection and urinary tract infection. Non-infectious complications included postoperative ileus (occurring within the first 5 days post-operation), bleeding at the anastomosis site or an intra-abdominal hematoma necessitating transfusion, interventions such as pig-tail drain placement or surgery, close monitoring due to massive hematochezia (occurring more than three times per a day), and thromboembolic events, including portal vein thrombosis.

Discrete variables were compared using the χ2 test, while continuous variables were assessed using the unpaired Student’s t-test. To minimize treatment selection bias and potential confounding in this observational study, rigorous adjustments were made for significant differences in patient characteristics through weighted logistic regression models, employing the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) technique[10]. With IPTW, the weights for patients who received the CSA were calculated as the inverse of “1 - propensity score”, while the weights for patients who received the DSA were calculated as the inverse of the propensity score. Propensity scores were estimated through multiple logistic regression analyses. All prespecified covariates were included in the full non-parsimonious models comparing DSA and CSA treatments. The discrimination and calibration abilities of each propensity score model were evaluated using the C statistic and the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic. Baseline covariates between the two groups were compared before and after weighting as standardized mean difference, in which a difference of < 15% was deemed acceptable. All reported P values are two-sided, with values of P < 0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, United States).

The study cohort comprised 175 patients, with a mean follow-up period of 20.7 ± 13.7 months. Among them, 92 patients were part of the DSA group, while 83 patients were in the CSA group. The DSA group had a shorter follow-up period compared with the CSA group (17.2 ± 10.8 months vs 24.6 ± 15.5 months, P = 0.001). Regarding the Montreal classification location, a higher proportion of patients in the DSA group had a colonic location compared with the CSA group, showing a statistically significant difference (14.1% vs 2.4%, P = 0.021) (Table 1). In order characteristics such as age at diagnosis and operation, sex, body mass index at operation, history of previous abdominal operation, history of perianal fistula, family history of CD, history of smoking, Montreal classification behavior, and preoperative medical treatment, no statistical differences were observed between the two groups. These baseline characteristics were adjusted using the IPTW to account for potential confounding factors in significant differences (Table 1).

| Variables | Delta-shaped | Conventional | P value | SMD1 | Delta-shaped | Conventional | SMD1 |

| n = 92 | n = 83 | n = 92 | n = 83 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean ± SD | 26.87 ± 9.25 | 28.10 ± 10.57 | 0.414 | 0.123 | 27.9 ± 9.29 | 27.53 ± 11.46 | 0.036 |

| Age at operation, years, mean ± SD | 35.22 ± 10.01 | 34.37 ± 11.47 | 0.604 | 0.078 | 34.88 ± 9.89 | 34.64 ± 11.51 | 0.022 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.607 | 0.095 | 0.019 | ||||

| Female | 26 (28.3) | 20 (24.1) | 22 (24.3) | 19 (23.5) | |||

| Male | 66 (71.7) | 63 (75.9) | 70 (75.7) | 64 (76.5) | |||

| Body mass index at operation, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 19.56 ± 3.10 | 20.12 ± 3.54 | 0.261 | 0.170 | 20.09 ± 3.43 | 19.82 ± 3.51 | 0.078 |

| History of previous abdominal operation, n (%) | 0.198 | 0.195 | 0.042 | ||||

| Yes | 27 (29.3) | 32 (38.6) | 33 (36.4) | 29 (34.4) | |||

| History of perianal fistula, n (%) | 0.645 | 0.145 | 0.075 | ||||

| None | 63 (68.5) | 62 (74.7) | 68 (74.2) | 64 (77.3) | |||

| Currently having perianal fistula | 5 (5.4) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (3.8) | |||

| Healed state after treatment | 24 (26.1) | 18 (21.7) | 20 (21.4) | 16 (18.9) | |||

| Family history of CD, n (%) | 0.709 | 0.079 | 0.025 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (3.3) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.8) | |||

| History of smoking, n (%) | 0.236 | 0.259 | 0.093 | ||||

| None | 53 (57.6) | 49 (59.0) | 51 (55.6) | 49 (59.3) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 26 (28.3) | 16 (19.3) | 21 (22.6) | 19 (22.4) | |||

| Current smoker | 13 (14.1) | 18 (21.7) | 20 (21.8) | 15 (18.3) | |||

| Montreal classification behavior, n (%) | 0.779 | 0.108 | 0.118 | ||||

| Non-stricturing, non-penetrating (B1) | 12 (13.0) | 8 (9.6) | 10 (11.3) | 12 (14.4) | |||

| Stricturing (B2) | 31 (33.7) | 29 (34.9) | 34 (37.3) | 27 (32.7) | |||

| Penetrating (B3) | 49 (53.3) | 46 (55.4) | 47 (51.4) | 44 (52.9) | |||

| Montreal classification location, n (%) | 0.021a | 0.439 | 0.041 | ||||

| Ileum (L1) | 46 (50.0) | 45 (54.2) | 45 (49.1) | 42 (51.1) | |||

| Colon (L2) | 13 (14.1) | 2 (2.4) | 8 (8.2) | 6 (7.7) | |||

| Ileocolon (L3) | 33 (35.9) | 36 (43.4) | 39 (42.7) | 34 (41.2) | |||

| Medical treatment just before surgery, n (%) | |||||||

| No medication | 23 (25.0) | 17 (20.5) | 0.477 | 0.108 | 20 (21.8) | 19 (22.3) | 0.013 |

| Immunomodulators, only | 27 (29.3) | 34 (41.0) | 0.107 | 0.245 | 33 (35.9) | 28 (33.8) | 0.043 |

| Anti-TNF-α antibodies, only | 21 (22.8) | 14 (16.9) | 0.325 | 0.150 | 18 (19.3) | 16 (19.0) | 0.006 |

| Corticosteroids, only | 5 (5.4) | 7 (8.4) | 0.433 | 0.118 | 6 (6.2) | 6 (6.6) | 0.018 |

| Combined immunomodulators with anti-TNF-α antibodies | 10 (10.9) | 10 (12.0) | 0.807 | 0.037 | 11 (12.1) | 12 (14.6) | 0.073 |

| Combined immunomodulators with corticosteroids | 5 (5.4) | 2 (2.4) | 0.448 | 0.156 | 4 (4.1) | 3 (3.6) | 0.028 |

| Combined anti-TNF-α antibodies with corticosteroids | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.2) | > 0.999 | 0.075 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | 0.032 |

In the DSA and CSA groups, the most common operative indications were fistula or abscess, accounting for 84.8% and 90.4% of cases, respectively. The next most common indication was stricture or obstruction in both groups, representing 13.0% and 6.0% of cases, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups concerning operative indication. Additionally, no statistical differences were found between the two groups for emergency operation, the operative approach (open vs laparoscopic), the distribution of operative types, or number of anastomoses (Table 2).

| Variables | Delta-shaped | Conventional | Before IPTW | After IPTW |

| n = 92 | n = 83 | P value | P value | |

| Operative indication, n (%) | 0.185 | 0.411 | ||

| Stricture or obstruction | 12 (13.0) | 5 (6.0) | ||

| Fistula (enteric-) or abscess | 78 (84.8) | 75 (90.4) | ||

| Perforation (peritonitis) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Emergency operation, n (%) | 0.425 | 0.430 | ||

| Yes | 2 (2.2) | 4 (4.8) | ||

| Operative approach, n (%) | 0.852 | 0.829 | ||

| Open | 18 (19.6) | 18 (21.7) | ||

| Laparoscopy | 74 (80.4) | 65 (78.3) | ||

| Operative name, n (%) | 0.425 | 0.160 | ||

| Ileocecal resection | 28 (30.4) | 25 (30.1) | ||

| Right hemicolectomy | 26 (28.3) | 17 (20.5) | ||

| Small bowel resection and anastomosis | 38 (41.3) | 41 (49.4) | ||

| Number of anastomosis, n (%) | 0.682 | 0.810 | ||

| 1 | 76 (82.6) | 71 (85.5) | ||

| 2 | 16 (17.4) | 12 (14.5) |

The DSA group had a statistically significant shorter hospital stay after surgery compared with the CSA group (5.7 ± 1.5 days vs 7.4 ± 3.7 days, P = 0.001). The shorter hospital stay in the DSA group was confirmed even after adjustment with IPTW (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Despite the use of the new anastomosis technique, there was no difference in operative time between the DSA and CSA groups (107.2 ± 25.2 minutes vs 112.5 ± 28.5 minutes, P = 0.192). There were no statistically significant differences in the amount of intraoperative blood loss, cases requiring postoperative transfusion, or the average number of packed red blood cell transfusions between the two groups. However, there was a significant difference in the distribution of intraoperative blood loss, with more patients in the DSA group experiencing blood loss (including blood loss less than 10 mL) compared with the CSA group (69.6% vs 53.0%, P = 0.031).

| Variables | Delta-shaped | Conventional | Before IPTW | After IPTW |

| n = 92 | n = 83 | P value | P value | |

| Hospital stay after surgery, days, mean ± SD | 5.67 ± 1.53 | 7.39 ± 3.69 | < 0.001a | < 0.001a |

| Operation time, minutes, mean ± SD | 107.23 ± 25.16 | 112.54 ± 28.48 | 0.192 | 0.480 |

| Intraoperative blood loss, n (%) | 0.075 | 0.031a | ||

| < 10 mL | 64 (69.6) | 44 (53.0) | ||

| 10-200 mL | 26 (28.3) | 35 (42.2) | ||

| > 200 mL | 2 (2.2) | 4 (4.8) | ||

| Transfusion after surgery, n (%) | 0.104 | 0.054 | ||

| Yes | 8 (8.7) | 14 (16.9) | ||

| No | 84 (91.3) | 119 (82.1) | ||

| Number of pack RBC after surgery, mean ± SD | 0.16 ± 0.72 | 0.35 ± 0.88 | 0.123 | 0.175 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | 15 (16.3) | 27 (32.5) | 0.014a | 0.002a |

| Number of complication, n (%) | 0.037a | 0.002a | ||

| 0 | 78 (84.8) | 58 (69.9) | ||

| 1 | 13 (14.1) | 20 (24.1) | ||

| 2 | 1 (1.1) | 5 (6.0) | ||

| Clavien-Dindo classification, n (%) | 0.021a | 0.006a | ||

| II | 11 (12.0) | 21 (25.3) | ||

| IIIa | 4 (4.3) | 3 (3.6) | ||

| IIIb | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | ||

| Infectious complications, n (%) | 10 (10.9) | 13 (15.7) | ||

| Wound | 5 (5.4) | 5 (6.0) | > 0.999 | 0.964 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 4 (4.3) | 4 (4.8) | > 0.999 | 0.603 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0.474 | 0.255 |

| Other infectious complication1 | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 0.604 | 0.432 |

| Non-infectious complications, n (%) | ||||

| Ileus | 4 (4.3) | 12 (14.5) | 0.033a | 0.022a |

| Bleeding | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.6) | 0.347 | 0.031a |

| Other2 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0.474 | 0.314 |

| Surgical recurrence, n (%) | 0.224 | 0.137 | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) |

The overall complication rate was significantly lower in the DSA group compared with the CSA group (16.3% vs 32.5%, P = 0.014). There was a significant difference in the Clavien-Dindo classification, which measures the severity of postoperative complications (DSA vs CSA for grade II: 12.0% vs 25.3%; grade IIIa: 4.3% vs 3.6%; and grade IIIb: 0% vs 3.6%, P = 0.006). The incidence of postoperative ileus and intra-abdominal hematoma were significantly lower in the DSA group compared with the CSA group (ileus: 4.3% vs 14.5%, P = 0.022; bleeding: 1.1% vs 3.6%, P = 0.031). There were no significant differences in the rate of anastomotic leak and anastomotic bleeding between the two groups (Table 3). The DSA group demonstrated a significantly lower risk of overall postoperative complications compared with the CSA group in both the crude regression model and the weighted logistic regression model (Table 4). Although the follow-up period was relatively short, there were 2 cases of surgical recurrence in the CSA group, whereas there were no cases of surgical recurrence in the DSA group (P = 0.137).

| Overall complication | No | Yes | Logistic regression analysis | ||||

| Model | Anastomosis | OR | 95%CI | P value | |||

| Crude model | |||||||

| Conventional, n (%) | 56 (64.5) | 27 (32.5) | 1 | ||||

| Delta, n (%) | 77 (83.7) | 15 (16.3) | 0.404 | 0.197 | 0.829 | 0.014a,2 | |

| Weighted model with IPTW1 | |||||||

| Conventional, n (%) | 54 (65.1) | 29 (34.9) | 1 | ||||

| Delta, n (%) | 79 (85.7) | 13 (14.3) | 0.312 | 0.149 | 0.653 | 0.002a | |

This study introduced a novel technique that modified the CSA technique by incorporating a 90° vertical closure of the open window. This DSA technique has several advantages including a wider actual anastomosis lumen compared with the CSA technique, mesentery side concealment achieved through mesenteric alignment in the middle of the second staple line, and a shorter operation times. We developed the DSA technique to overcome shortcomings of the Kono-S anastomosis technique. The Kono-S anastomosis technique creates a supporting column located posteriorly on the mesenteric border and has been shown to have lower surgical recurrence rates than conventional anastomosis techniques[7]. The SuPREMe-CD trial further demonstrated a significant reduction of clinical and endoscopic recurrence with Kono-S anastomosis compared with the conventional side-to-side anastomosis[11]. Despite these benefits, Kono-S anastomosis involves longer operation times and complex surgical techniques.

Although long-term recurrence results are still needed, the results of this study suggest that DSA offers the advantage of preventing corners and external exposure of the mesentery side without extending operation times compared with CSA. This technique aligns with stapled Kono-S anastomosis and is characterized by minimal deviation from the CSA technique, ensuring speed and reproducibility. DSA shares similarities with the mesentery alignment of the Kono-S anastomosis, placing the mesenteric side in the middle of the stapled line[12]. This configuration may be advantageous in addressing complications such as CD-related ulcers or fistulas. Furthermore, while DSA employs side-to-side anasto

Despite improvements in biologic treatments, surgery still remains a key treatment modality for CD[13-15]. IBD surgeons face challenges in minimizing surgical interventions and avoiding repeat surgeries due to surgical or disease-related reasons. The CSA technique can sometimes lead to enterocutaneous fistulas or intra-abdominal abscesses due to the recurrence of penetrating disease, particularly around the protruding corner area (Figure 3). These patterns of recurrence suggest potential etiologies such as fecal stasis or inflammation-driven mesentery side issues[12,16].

In contrast, the DSA technique replaces the transverse closure with a vertical closure, positions the mesentery side at the center of the stapled line, and allows for straightforward invagination sutures, all of which help prevent complications and recurrence. We anticipate that the DSA technique may reduce clinical, endoscopic, and surgical recurrence of CD by optimizing the closure site positioning in the center of the mesentery and improving the lumen width. Although the follow-up period of our study was short, two cases of surgical recurrence were noted in the CSA group, whereas none were observed in the DSA group. The DSA technique offers advantages over the existing CSA technique in terms of wider anastomotic lumen and mesenteric alignment, which may lead to improved long-term recurrence-free outcomes.

The DSA technique demonstrated significantly lower short-term postoperative complications compared with the CSA technique, particularly concerning the incidence of ileus. These results may be attributed to the shorter operative time and the relatively wide, appropriate lumen shape provided by the DSA technique. While the hand-sewn Kono-S anastomosis, which excludes the mesentery, has gained popularity for its comparable postoperative outcomes and reduced burden of anastomotic recurrence after intestinal resection for CD[5,6,17,18], this study introduced a simpler technique with a shorter operative time and a lower rate of postoperative complications. Side-to-side stapled anastomosis can result in a lower leak rate, fewer postoperative complications, reduced duration of surgery, and shorter hospital stays compared with end-to-end hand-sewn anastomosis after CD resection[19-21].

Recently, stapled Kono-S anastomosis was introduced, combining the benefits of stapled anastomosis and Kono-S anastomosis[8]. However, this combined technique has cost and operative time limitations due to the increased number of staplings compared with the CSA technique. Another method, stapled antimesenteric functional end-to-end anastomosis, also incorporates concepts of Kono-S anastomosis[9]. Although this approach hides both distal end parts on the mesentery side, it requires some hand-sewn anastomosis and uses more staples than the CSA technique. Given these factors, the DSA technique offers a meaningful balance between concept and practicality compared to the newer forms of stapled Kono-S anastomosis.

This study had inherent limitations typical of a retrospective study. First, it was conducted at a single center with a relatively small sample size, which may lead to sampling error and selection bias. However, all patients who had surgery recently were included. IPTW was implemented to reduce sampling error, but differences in Montreal classification location remained. Although there were more cases in the colon in the DSA group, only patients with right colon involvement were included. In addition, the operation name was performed with ileocecal resection or right hemico

The DSA technique introduced in this study appears to be a safe and more suitable option for CD surgery compared with the CSA technique. The DSA technique demonstrated comparable or superior outcomes in terms of operative time and postoperative complications. Additionally, the DSA technique combined the conceptual aspects of antimesentery anastomosis with the practical benefits of an improved anastomosis shape. In the future, further research is warranted to examine the long-term postoperative complications as well as clinical, endoscopic, and surgical recurrence.

The statistical part of this study was conducted by Min-Ju Kim of the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

| 1. | Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1980] [Article Influence: 220.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (113)] |

| 2. | Jones DW, Finlayson SR. Trends in surgery for Crohn's disease in the era of infliximab. Ann Surg. 2010;252:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wolters FL, Russel MG, Stockbrügger RW. Systematic review: has disease outcome in Crohn's disease changed during the last four decades? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:483-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1697-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kono T, Fichera A, Maeda K, Sakai Y, Ohge H, Krane M, Katsuno H, Fujiya M. Kono-S Anastomosis for Surgical Prophylaxis of Anastomotic Recurrence in Crohn's Disease: an International Multicenter Study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:783-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alshantti A, Hind D, Hancock L, Brown SR. The role of Kono-S anastomosis and mesenteric resection in reducing recurrence after surgery for Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kono T, Ashida T, Ebisawa Y, Chisato N, Okamoto K, Katsuno H, Maeda K, Fujiya M, Kohgo Y, Furukawa H. A new antimesenteric functional end-to-end handsewn anastomosis: surgical prevention of anastomotic recurrence in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bislenghi G, Devriendt S, Wolthuis A, D'Hoore A. Totally stapled Kono-S anastomosis for Crohn's disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Duan M, Wu E, Xi Y, Wu Y, Gong J, Zhu W, Li Y. Stapled Antimesenteric Functional End-to-End Anastomosis Following Intestinal Resection for Crohn's Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66:e4-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | D'Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265-2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luglio G, Rispo A, Imperatore N, Giglio MC, Amendola A, Tropeano FP, Peltrini R, Castiglione F, De Palma GD, Bucci L. Surgical Prevention of Anastomotic Recurrence by Excluding Mesentery in Crohn's Disease: The SuPREMe-CD Study - A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2020;272:210-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coffey CJ, Kiernan MG, Sahebally SM, Jarrar A, Burke JP, Kiely PA, Shen B, Waldron D, Peirce C, Moloney M, Skelly M, Tibbitts P, Hidayat H, Faul PN, Healy V, O'Leary PD, Walsh LG, Dockery P, O'Connell RP, Martin ST, Shanahan F, Fiocchi C, Dunne CP. Inclusion of the Mesentery in Ileocolic Resection for Crohn's Disease is Associated With Reduced Surgical Recurrence. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1139-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, Debruyn J, Jette N, Fiest KM, Frolkis T, Barkema HW, Rioux KP, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Wiebe S, Kaplan GG. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 687] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bouguen G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Surgery for adult Crohn's disease: what is the actual risk? Gut. 2011;60:1178-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wong DJ, Roth EM, Feuerstein JD, Poylin VY. Surgery in the age of biologics. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2019;7:77-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Linskens RK, Huijsdens XW, Savelkoul PH, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Meuwissen SG. The bacterial flora in inflammatory bowel disease: current insights in pathogenesis and the influence of antibiotics and probiotics. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2001;29-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kono T, Fichera A. Surgical Treatment for Crohn's Disease: A Role of Kono-S Anastomosis in the West. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ng CH, Chin YH, Lin SY, Koh JWH, Lieske B, Koh FH, Chong CS, Foo FJ. Kono-S anastomosis for Crohn's disease: a systemic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Surg Today. 2021;51:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yoon YS, Stocchi L, Holubar S, Aiello A, Shawki S, Gorgun E, Steele SR, Delaney CP, Hull T. When should we add a diverting loop ileostomy to laparoscopic ileocolic resection for primary Crohn's disease? Surg Endosc. 2021;35:2543-2557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Anuj P, Yoon YS, Yu CS, Lee JL, Kim CW, Park IJ, Lim SB, Kim JC. Does Anastomosis Configuration Influence Long-term Outcomes in Patients With Crohn Disease? Ann Coloproctol. 2017;33:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, Doherty G, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Fiorino G, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gomollon F, González Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Kucharzik T, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Stassen L, Torres J, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Zmora O. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Surgical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:155-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/