Published online Dec 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i12.433

Peer-review started: August 15, 2019

First decision: September 21, 2019

Revised: October 5, 2019

Accepted: November 20, 2019

Article in press: November 20, 2019

Published online: December 27, 2019

Processing time: 116 Days and 18.9 Hours

Atraumatic splenic rupture (ASR) accounts for just over 3% of all cases of splenic rupture and is associated with a high mortality rate. The most common culprit is acute infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) but other documented aetiologies include neoplasia, other viral/bacterial infections, acute and chronic pancreatitis, amyloidosis and anticoagulant medications. There are four previous reports of cocaine-associated ASR but never before has it been documented in combination with concurrent acute EBV infection.

A 21-year-old man presented to hospital with acute left shoulder pain which radiated to the right shoulder and upper abdomen. He denied any history of recent trauma and had no relevant past medical history. He took no regular prescription medications but had used cocaine within the previous 24 h. Investigations revealed splenomegaly, a Grade 3 subcapsular splenic haematoma, moderate haemoperitoneum and an incidental 9 mm splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. There was also serological evidence of acute EBV infection. Prophylactic endovascular embolisation of the pseudoaneurysm was performed and the splenic rupture was managed non-operatively. The patient remained admitted in hospital for seven days and did not require any transfusion of blood products. Serial imaging showed complete resolution of the haemoperitoneum after 5 wk. The importance of abstinence from illicit drug use was emphasised to the patient but it is unknown whether or not he remains compliant.

This case demonstrates that ASR is a rare condition that can result from acute EBV infection and cocaine ingestion and requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose clinically.

Core tip: Atraumatic splenic rupture (ASR) is an uncommon condition that carries a high mortality rate if not recognised early. We describe the case of a 21-year-old man who suffered ASR as a result of a both acute Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and recent cocaine ingestion. An incidental splenic artery pseudoaneurysm was also discovered on imaging which required endovascular embolisation. An association between ASR, acute EBV infection, cocaine use and splenic artery pseudoaneurysm has never been described previously in the literature. ASR requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose clinically and requires prompt, appropriate management to reduce morbidity and mortality.

- Citation: Kwok AMF. Atraumatic splenic rupture after cocaine use and acute Epstein-Barr virus infection: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(12): 433-442

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i12/433.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i12.433

Splenic rupture is traditionally observed in the context of trauma to the upper abdomen or lower left thoracic region. Increasingly there are reports of atraumatic splenic rupture (ASR) occurring in the absence of an obvious precipitant and a number of mechanisms have been proposed in the literature. The overall incidence of ASR is poorly defined but is thought to represent around 3% of all splenic ruptures[1]. Infectious mononucleosis, caused by acute infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), has been implicated as the single largest contributor to this phenomenon[2]. A number of cases have also been observed in patients taking newer oral anticoagulant medications, such as the direct Factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban[3,4]. Irrespective of the underlying cause mortality from ASR is high at 12.2%, but had approached 30% in earlier reports[2,5].

We aim to raise awareness of this diagnosis to facilitate its prompt recognition in a patient with acute abdominal pain and clinical evidence of bleeding without a history of trauma or anticoagulant use. This is essential to arranging early management and to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

We present the case of a 21-year-old man who presented with haemoperitoneum secondary to an acute ASR. Closer questioning and further investigations revealed that he had two simultaneous risk factors for ASR as well as an incidental splenic artery pseudoaneurysm, which itself is another risk factor for spontaneous haemoperitoneum.

A 21-year-old man presented to our institution with sudden onset pain in the left trapezius and shoulder.

At the time of symptom onset he was engaged at work driving heavy machinery, but denied any recent history of injury or trauma. He had not been recently unwell and denied any constitutional symptoms such as weight loss or fever. Over the following five hours his pain began to also affect his right shoulder and there was associated generalised abdominal pain of increasing severity, most marked in the left and right upper quadrants.

The patient had no significant past medical history, specifically never having had an episode of pancreatitis before. He was not taking any regular prescription medications but upon closer questioning admitted to occasional recreational cocaine use, the most recent ingestion of which was within 24 h of hospital admission.

The patient had no significant family history of medical illness.

Clinical examination revealed a well-looking man in no obvious distress. Although he was mildly tachypnoeic (20 breaths/min) his other vital signs were normal (heart rate 78 beats/min, blood pressure 129/84 mmHg, temperature 36.9 ºC and oxygen saturations 99% on room air). His abdomen was not distended but there was generalised percussion tenderness most profound in the left and right upper quadrants. Examination of his shoulders revealed no focal tenderness and full active and passive ranges of motion with preserved motor and sensory function.

Initial biochemical findings included a haemoglobin of 138 g/L, leucocyte count 4.74 × 109/L, platelets 197 × 109/L and international normalised ratio of 1.1. Plain chest X-ray was unremarkable. Repeat blood tests were performed after five hours due to the increasing severity of his symptoms which revealed a haemoglobin of 99 g/L, indicating a significant decrease from the initial value.

The combination of worsening abdominal pain and a falling haemoglobin prompted a computed tomography (CT) scan of his abdomen and pelvis which was conducted with both oral and IV contrast in the portal venous phase. It revealed a large amount of high-density fluid within the abdominal cavity, consistent with haemoperitoneum. Moderate splenomegaly (16.4 cm × 9.9 cm × 7.4 cm) and an overlying Grade 3 subcapsular splenic haematoma[6] were also noted (Figure 1).

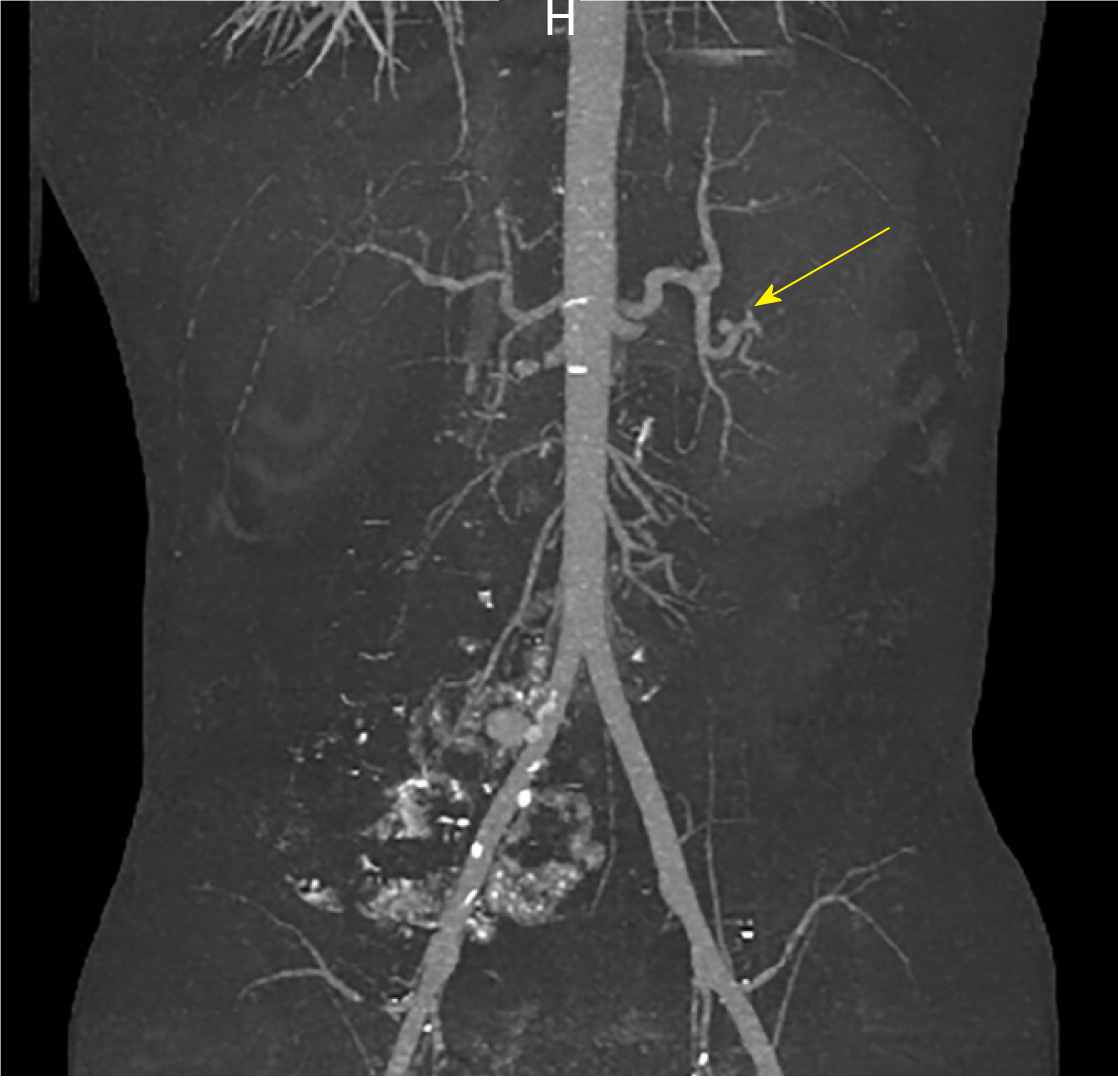

A repeat CT with IV contrast in the arterial phase (CT angiogram) was then performed to exclude the presence of active arterial bleeding. Although no active extravasation was observed on this study, an incidental splenic artery pseudo-aneurysm measuring 9.1 mm × 8.3 mm × 8.1 mm was discovered near the superolateral aspect of the spleen (Figures 2 and 3).

In the search for an underlying precipitant, viral serological testing was ordered despite the absence of typical prodromal symptoms. Both IgM and IgG antibodies against EBV viral capsid antigen were detected 24 h later.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is ASR due to a combination of recent cocaine ingestion and acute EBV infection. There was also an incidental finding of a 9.1 mm non-bleeding splenic artery pseudoaneurysm at the superolateral aspect of the spleen.

The patient was resuscitated with intravenous crystalloid fluids and, despite his haemodynamic stability, a precautionary intensive care review was requested due to the degree of haemoperitoneum demonstrated on CT and his falling haemoglobin level. Transfusion of blood products was not performed due to his stable clinical status and lack of any underlying coagulopathy.

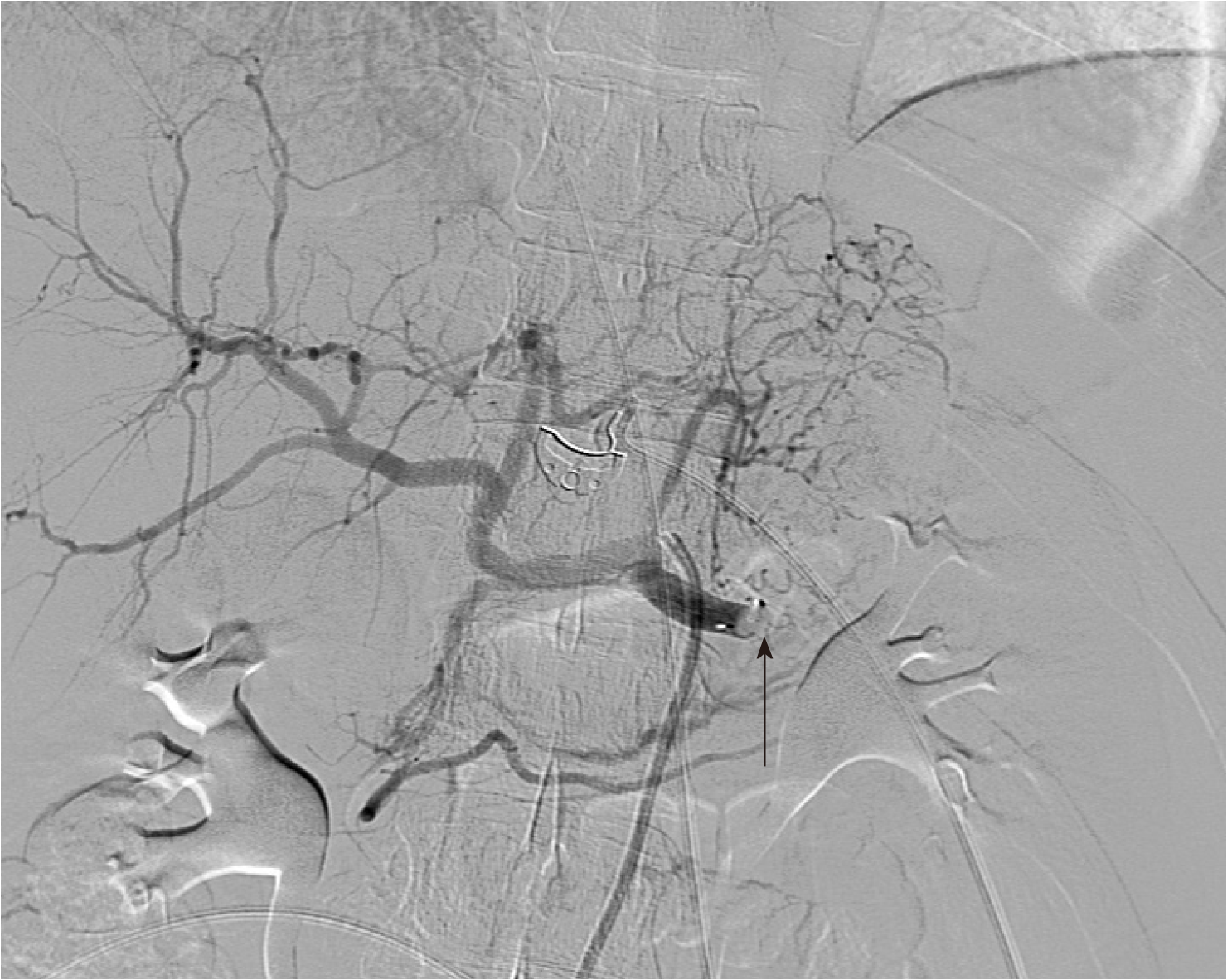

Upon incidental discovery of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm, it was decided that prophylactic intervention would be appropriate to reduce the chance of spontaneous rupture. After discussion with the consultant radiologist, formal catheter angiography was performed via a right common femoral artery puncture and a 8 mm × 13.5 mm Amplatzer Vascular Plug (St. Jude MedicalTM, Minnesota, United States) was deployed within the splenic artery between the dorsal pancreatic artery and the pancreatic magna artery (Figure 4). Subsequent angiography demonstrated successful occlusion of the proximal splenic artery and an absence of distal flow (Figures 5 and 6).

The patient was allowed to mobilise gently around the ward and given a normal diet. He remained clinically stable throughout the remainder of his admission with haemoglobin levels being maintained at or above 105 g/L without the need for blood transfusion. His abdominal pain gradually subsided and there was no clinical evidence of rebleeding. Progress CT on day 5 demonstrated a marked reduction in the size of the splenic haematoma and the amount of free intraperitoneal blood (Figure 7). No splenic infarction was noted on this repeat scan, likely owing to the presence of a rich collateral arterial supply.

The patient was discharged uneventfully on day 7 of admission with advice to avoid exertional activity or contact sports for 4 wk and to cease illicit drug use indefinitely.

At initial 3-wk follow-up he remained well and there was no evidence of post-procedural complications. Advice to cease cocaine was re-emphasised to the patient. A progress CT performed 2 wk after the initial review demonstrated complete resolution of haemoperitoneum and almost-complete resolution of the splenic subcapsular haematoma. The patient has not re-presented to hospital with abdominal pain or any other complaint in the following five months. It is unknown whether or not he continues to use recreational cocaine.

ASR is a potentially life-threatening condition which affects males twice as frequently as females and predominantly occurs in middle age (mean age 45 years)[2]. Due to the of lack an internationally-recognised consensus regarding classification, the literature consists of sporadic case reports which attribute various causes to making the spleen vulnerable to spontaneous bleeding in the absence of trauma. Although acute EBV infection is cited as the most common cause of ASR[2], less common causes include cytomegalovirus infection[7], tuberculosis[8], meliodosis (infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei)[9], amyloidosis[10], systemic lupus erythematosus[11] and splenic vein thrombosis due to prothrombin gene mutation[12]. There are even reports of ASR being caused by an ectopic pregnancy[13] and splenic metastases of melanoma[14].

In an attempt to bring together the plethora of known or suspected aetiologies, Renzulli et al[2] performed a systematic review of ASR and devised a classification system comprising of six main groups: Neoplastic disorders, infectious disorders, inflammatory disorders, iatrogenic (pharmacological) causes, mechanical disorders and idiopathic (those involving a normal spleen). As a group, neoplasia is the most common aetiology (30.3%) and consists mainly of haematological conditions such as lymphoma, leukaemia and myeloproliferative disorders. Infectious disorders are the 2nd most common cause as a group (27.3%) although EBV was the single most common cause of ASR overall (11.0%). Anticoagulants are the main cause within the pharmacological group, with one review attributing up to 33% of cases of ASR to medications such as apixaban and rivaroxaban[3]. Interestingly, only 7% of cases of ASR were found to be truly idiopathic where no other predisposing factors could be identified and where the spleen was found to be normal following pathological examination, indicating that the vast majority of cases (93%) are associated with underlying systemic conditions or histological abnormalities of the spleen. Splenomegaly was noted to be a common feature in ASR and is found in 55% of cases.

With respect to operative rates and mortality, Renzulli et al[2] found that 85.3% of patients had surgery within 24 h of diagnosis (with an associated mortality rate of 7.4%), while the remaining 14.7% of patients who were managed conservatively had a mortality rate of 4.4%. Non-operative management was successful in up to 80% of those who were initially managed conservatively, yielding overall splenic salvage rates of 13.7%. Overall mortality was 12.2% but was found to be higher in patients over 40 years of age. No sex-based difference was found.

Splenic rupture is the leading cause of death in infectious mononucleosis and should be considered in any patient with abdominal pain and known or suspected acute EBV infection[15,16]. The presence of left shoulder pain in this setting is known as Kehr’s sign and is present in 17% of patients with ASR[17]. Diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis consists of appropriate clinical findings (the “classical triad” of fever, pharyngitis and lymphadenopathy) and serological evidence (detection of anti-viral capsid antigen IgM antibodies)[18]. Approximately 0.5% of these patients will suffer from ASR with an associated mortality rate of 9%-30%[5,19,20]. Rupture is most common within the first 3 wk but may present as late as 8 wk after acute infection. Predisposition to ASR in this setting is thought to arise from mononuclear cell proliferation causing splenomegaly, vasculitis of the larger follicular veins and parenchymal and capsular stretch and inflammation[5,20].

Cocaine is a potent sympathomimetic and causes vasoconstriction and elevation of blood pressure by blocking noradrenaline reuptake at the synaptic level. The resultant hypertension can be severe enough to precipitate haemorrhagic cerebral infarction while vasospasm can result in ischaemic strokes and impaired mucosal blood flow to the gastrointestinal organs. Increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor after cocaine ingestion increases vascular permeability which may also increase the likelihood of haemorrhagic transformation in ischaemic strokes. Cases of gastroduodenal perforation and bowel ischaemia have also been attributed to cocaine use[21]. In cases of ASR associated with recent cocaine ingestion, it has been postulated that the initiating event is the development of splenic infarctions as a result of profound vasospasm. Increased vascular permeability and hypertension then result in haemorrhagic transformation and eventual capsular rupture[22]. To our knowledge there are only four previous reports of cocaine-associated ASR[21-23], making this quite a rare phenomenon.

Following splenic rupture, autotransplantation of splenic tissue into the peritoneal cavity is a well-known phenomenon and was named “splenosis” by Buchbinder and Lipkoff in 1939[24]. It is usually described in the setting of previous traumatic rupture but its occurrence following ASR is highly plausible. Splenosis is present in up to 76% of patients who have undergone splenectomy for trauma and is most commonly found in the pelvis but has also been described on the greater and lesser omenta, the diaphragm, small and large bowel, in subcutaneous tissue beneath a surgical scar, within the parenchyma of the liver and even within the thorax[25]. It can be distinguished from congenital splenunculi by the lack of a true hilum and by its blood supply being derived from multiple peripheral feeding vessels penetrating capsular tissue[26].

The clinical significance of splenosis is twofold: Firstly, awareness and recognition of this condition is required to differentiate it from carcinomatosis or endometriosis if it is encountered intra-operatively[24]. Secondly, it must be considered when there is recurrence of haematological conditions (such as idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura, ITP) following splenectomy[25]. Splenosis is usually asymptomatic and may even provide some degree of immunological function in the absence of the spleen[27]. If the condition is suspected (for example, recurrent ITP after splenectomy), a 99Tc scintigram using heat-damaged erythrocytes is the most sensitive and specific investigation to detect residual splenic tissue and is the imaging modality of choice[27].

Another possible sequela of splenic rupture is the development of splenic pseudocysts. Although they are asymptomatic in up to 60% of cases, patients may present with pseudocyst rupture or infection or with compression of surrounding structures when significant enlargement has occurred[28]. Diagnosis is made based on imaging and a history of prior splenic injury, but they must be differentiated from true splenic cysts such as those found in hydatid disease. Intervention is indicated when pseudocysts become symptomatic. Total splenectomy was traditionally performed but the theoretical risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection has increased enthusiasm for spleen-preserving approaches such as cystectomy and partial splenectomy. Laparoscopic approaches have been performed successfully[29] and one report described the use of indocyanine green in the resection of a large pseudocyst in order to help differentiate it from normal parenchyma and hence maximise preservation of normal splenic tissue[28]. Percutaneous drainage and surgical deroofing are less invasive but are associated with high recurrence rates of up to 40%[29].

Splenic artery pseudoaneurysms (SAPA) are the most common form of all visceral artery pseudoaneurysms and account for 46%[30]. Unlike true visceral artery aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms are more commonly encountered in males and are much more prone to rupture (76% vs 3%)[31,32]. SAPA are seen almost exclusively in patients with chronic pancreatitis, which causes long-standing inflammation and erosion of the vessel wall that compromises its integrity, although a small number are iatrogenic from surgical or radiological procedures[33]. Between 4.5%-17% of all patients with chronic pancreatitis have SAPA and although most are asymptomatic, rupture is fatal in 90% of cases[32,34,35]. The most common site of rupture is into a pancreatic pseudocyst which causes bleeding into the pancreatic duct and subsequently the gastrointestinal tract[33]. Only 10% of SAPA rupture freely into the peritoneal cavity[32]. Risk of rupture does not correlate with size and hence all SAPA should be treated when discovered. Endovascular plugs, coils or thrombin embolisation are the usual methods[32-34], but other options include splenic artery ligation and splenic artery stent grafting[30,33]. Splenectomy is reserved for cases in which more conservative measures have failed, are inappropriate (due to clinical instability) or are not available. Possible complications after endovascular management of SAPA occur in 12.5% and include splenic infarction, coil/stent migration, rebleeding and puncture-site haematoma[31].

Our patient had two known risk factors for ASR as well as an incidental splenic artery pseudoaneurysm which itself is a risk factor for spontaneous rupture and acute haemorrhage. The timing of the recent cocaine ingestion makes it a likely contributing factor to the development of ASR along with acute EBV infection. Our patient had both splenomegaly and Kehr’s sign, which are found in 55% and 17% of cases respectively, but unlike previous cases the acute EBV infection was subclinical and otherwise asymptomatic. In keeping with the literature, our patient had pre-emptive embolisation of an incidentally-detected SAPA owing to its high risk of rupture.

In summary, this combination of acute EBV infection and recent cocaine use causing ASR, in association with an incidental splenic artery pseudoaneurysm, is an interesting variant of a recognised phenomenon that has not been previously reported in the literature. Opportunities for further research in this area are numerous, given that non-operative management is being employed with increasing frequency and that the wide availability of CT scanning is likely to see an increase in the number of cases of ASR being diagnosed. Nevertheless, since only 7% are considered idiopathic, this implies that a large number of cases are associated with an underlying abnormality of the spleen. A longitudinal cohort study may be employed to ascertain the long-term incidence of primary splenic disorders in patients who undergo operative and non-operative management for ASR. Additionally, routine questioning of patients with ASR regarding illicit drug use may be helpful in ascertaining their role in its pathogenesis.

ASR is an uncommon event and accounts for 3% of all splenic ruptures. It can be classified as pathological (93%) or idiopathic (7%), with pathological causes including neoplasia, infections, inflammation and iatrogenic injury. Infectious mononucleosis is the largest single cause of ASR worldwide, even when otherwise asymptomatic as in our patient. This case highlights the importance of early recognition of ASR, the possibility of success with a non-operative approach (depending on the Grade of injury) and the need for prompt intervention for visceral artery pseudoaneurysms due to their high risk of rupture, independent of size. The combination of ASR, acute EBV infection, recent cocaine use and the presence of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm has not been previously described in the literature.

| 1. | Liu J, Feng Y, Li A, Liu C, Li F. Diagnosis and Treatment of Atraumatic Splenic Rupture: Experience of 8 Cases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:5827694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1114-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lowry LE, Goldner JA. Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with apixaban: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagaraja V, Cranney G, Kushwaha V. Spontaneous splenic rupture due to rivaroxaban. Drug Ther Bull. 2018;56:136-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Konvolinka CW, Wyatt DB. Splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST). Injury scoring scale: A resource for trauma care professionals 2019. Available from: http://www.aast.org/Library/TraumaTools/InjuryScoringScales.aspx. |

| 7. | Rogues AM, Dupon M, Cales V, Malou M, Paty MC, Le Bail B, Lacut JY. Spontaneous splenic rupture: an uncommon complication of cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect. 1994;29:83-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tang T, Hsu Y, Lee JJ. Disseminated tuberculosis with splenic tuberculosis abscess rupture. A rare presentation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:829-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chou DW, Lin YW. Splenic Infarction and Rupture Due to Melioidosis. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:633-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Báez-García Jde J, Martínez-Hernández Magro P, Iriarte-Gallego G, Báez-Aviña JA. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen secondary to amyloidosis. Cir Cir. 2010;78:533-537. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Cruz AJ, Castro A. Systemic lupus erythaematosus presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arachchi A, Van Schoor L, Wang L, Smith C, Heng L. Rare case of spontaneous splenic rupture. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E338-E339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu BQ, Zhu F, Jiang Y, Sun DL. Case of spontaneous splenic rupture caused by ectopic pregnancy in the spleen. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:1778-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Buzbee TM, Legha SS. Spontaneous rupture of spleen in a patient with splenic metastasis of melanoma. A case report. Tumori. 1992;78:47-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De Silva S. Identification and management of nontraumatic splenic rupture. J Perioper Pract. 2017;27:296-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lennon P, Crotty M, Fenton JE. Infectious mononucleosis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mourato Nunes I, Pedroso AI, Carvalho R, Ramos A. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and spontaneous rupture of spleen. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lam GY, Chan AK, Powis JE. Possible infectious causes of spontaneous splenic rupture: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barnwell J, Deol PS. Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to Epstein-Barr virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sergent SR, Johnson SM, Ashurst J, Johnston G. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Atraumatic Spleen Laceration Presenting with Neck and Shoulder Pain. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:774-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Karthik N, Gnanapandithan K. Cocaine Use and Splenic Rupture: A Rare Yet Serious Association. Clin Pract. 2016;6:868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Azar F, Brownson E, Dechert T. Cocaine-associated hemoperitoneum following atraumatic splenic rupture: a case report and literature review. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khan AN, Casaubon JT, Paul Regan J, Monroe L. Cocaine-induced splenic rupture. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjx054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mccann WJ. Splenosis: Rupture of spleen, with splenic implants; review of literature and report of case. Br Med J. 1956;1:1271-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Barbaros U, Dinççağ A, Kabul E. Minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of splenosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lui EH, Lau KK. Intra-abdominal splenosis: how clinical history and imaging features averted an invasive procedure for tissue diagnosis. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:342-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sikov WM, Schiffman FJ, Weaver M, Dyckman J, Shulman R, Torgan P. Splenosis presenting as occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:56-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Aggarwal RK, Mohanty BB, Prasad A. Laparoscopic splenic pseudocyst management using indocyanine green dye: An adjunct tool for better surgical outcome. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sarwal A, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Chowbey P. Laparoscopic splenectomy for large splenic pseudocyst: A rare case report and review of literature. J Minim Access Surg. 2019;15:77-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shuaib W, Tiwana MH, Vijayasarathi A, Sadiq MF, Anderson S, Amin N, Khosa F. Imaging of vascular pseudoaneurysms in the thorax and abdomen. Clin Imaging. 2015;39:352-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pitton MB, Dappa E, Jungmann F, Kloeckner R, Schotten S, Wirth GM, Mittler J, Lang H, Mildenberger P, Kreitner KF, Oberholzer K, Dueber C. Visceral artery aneurysms: Incidence, management, and outcome analysis in a tertiary care center over one decade. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2004-2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ballinas-Oseguera GA, Martínez-Ordaz JL, Sinco-Nájera TG, Caballero-Luengas C, Arellano-Sotelo J, Blanco-Benavides R. Management of pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery: report of two cases. Cir Cir. 2011;79:246-251, 268-273. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Salemis NS, Boubousis G, Lagoudianakis E. Massive Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Due to a Ruptured Splenic Artery Pseudoaneurysm. Am Surg. 2016;82:e338-e340. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Hassan T, Khan F, Kyprianou A. A Not So Benign Abdomen! Gastroenterology. 2016;150:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Badour S, Mukherji D, Faraj W, Haydar A. Diagnosis of double splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: CT scan versus angiography. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kanat BH, Losanoff JE, Mohamed A, Rubbini M, Vagholkar KS-Editor: Yan JPL-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ