Published online Feb 27, 2018. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v10.i2.13

Peer-review started: November 15, 2017

First decision: December 8, 2017

Revised: December 9, 2017

Accepted: February 5, 2018

Article in press: February 6, 2018

Published online: February 27, 2018

Processing time: 104 Days and 0.5 Hours

To investigate the efficacy and safety of transcutaneous electroacupuncture (TEA) to alleviate postoperative ileus (POI) after gastrectomy.

From April 2014 to February 2017, 63 gastric cancer patients were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China. After gastrectomy, the patients were randomly allocated to the TEA (n = 33) or control (n = 30) group. The patients in the TEA group received 1 h TEA on Neiguan (ST36) and Zusanli (PC6) twice daily in the morning and afternoon until they passed flatus. The main outcomes were hours to the first flatus or bowel movement, time to nasogastric tube removal, time to liquid and semi-liquid diet, and hospital stay. The secondary outcomes included postoperative symptom assessment and complications.

Time to first flatus in the TEA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (73.19 ± 15.61 vs 82.82 ± 20.25 h, P = 0.038), especially for open gastrectomy (76.53 ± 14.29 vs 87.23 ± 20.75 h, P = 0.048). Bowel sounds on day 2 in the TEA group were significantly greater than in the control group (2.30 ± 2.61/min vs 1.05 ± 1.26/min, P = 0.017). Time to nasogastric tube removal in the TEA group was earlier than in the control group (4.22 ± 1.01 vs 4.97 ± 1.67 d, P = 0.049), as well as the time to liquid diet (5.0 ± 1.34 vs 5.83 ± 2.10 d, P = 0.039). Hospital stay in the TEA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (8.06 ± 1.75 vs 9.40 ± 3.09 d, P = 0.041). No significant differences in postoperative symptom assessment and complications were found between the groups. There was no severe adverse event related to TEA.

TEA accelerated bowel movements and alleviated POI after open gastrectomy and shortened hospital stay.

Core tip: Transcutaneous electroacupuncture (TEA) is a non-invasive and portable device. We applied TEA on postoperative gastric cancer patients to promote the bowel motility recovery. As far as we are concerned, it was the first attempt to investigate the efficacy and safety of TEA to alleviate postoperative ileus after gastrectomy.

- Citation: Chen KB, Lu YQ, Chen JD, Shi DK, Huang ZH, Zheng YX, Jin XL, Wang ZF, Zhang WD, Huang Y, Wu ZW, Zhang GP, Zhang H, Jiang YH, Chen L. Transcutaneous electroacupuncture alleviates postoperative ileus after gastrectomy: A randomized clinical trial. World J Gastrointest Surg 2018; 10(2): 13-20

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v10/i2/13.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v10.i2.13

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancy burdens in China, especially in economically less developed regions. The standard surgery is total or subtotal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer with radical-cure intention. However, postoperative ileus (POI) is not rare and causes symptoms such as abdominal pain, distention, nausea and vomiting due to the accumulation of gas and secretions[1]. This probably affects patient recovery, prolongs hospital stay, and increases cost. The treatment for POI includes fasting, nasogastric depression, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, parenteral nutrition, and exercise[2]. There is no clinical evidence for the use of prokinetic agents in POI and they may have severe adverse effects[3].

Modern electroacupuncture (EA) was developed from traditional Chinese medicine, which has been shown to accelerate gastric emptying and colonic motility[4,5]. A clinical study showed that electroacupuncture reduced the duration of POI after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer[6]. A study in dogs indicated that transcutaneous EA (TEA) on Neiguan (ST36) is as effective as EA in improving rectal distention-induced intestinal dysmotility[7]. It is non-invasive and more portable.

Therefore, we applied the novel technique of TEA in gastric cancer patients to promote postoperative recovery of bowel motility. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first attempt to investigate the efficacy and safety of TEA to alleviate POI after gastrectomy.

From April 2014 to February 2017, 63 patients were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China. All the patients underwent total or partial gastrectomy. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Gastric cancer patients without distal metastases; (2) age 18-85 years; (3) no severe history of cardiovascular, hepatic, hematological and renal diseases; (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score ≤ 2; and (5) written informed consent was obtained before the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Bile leakage or acute peritonitis; (2) cardiac pacemaker; (3) medication, such as metoclopramide, that affects bowel function; (4) history of chronic constipation; (5) history of abdominal surgery; (6) palliative gastrectomy; and (7) postoperative enema.

This study was designed collaboratively by doctors from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University and Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, United States. TEA was developed by Professor Jian-De Chen in the Clinical Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and gained safety certification in Zhejiang Province. The doctors who participated in the study were all trained in the TEA technique in Pace Translational Medical Research Center, Ningbo, China.

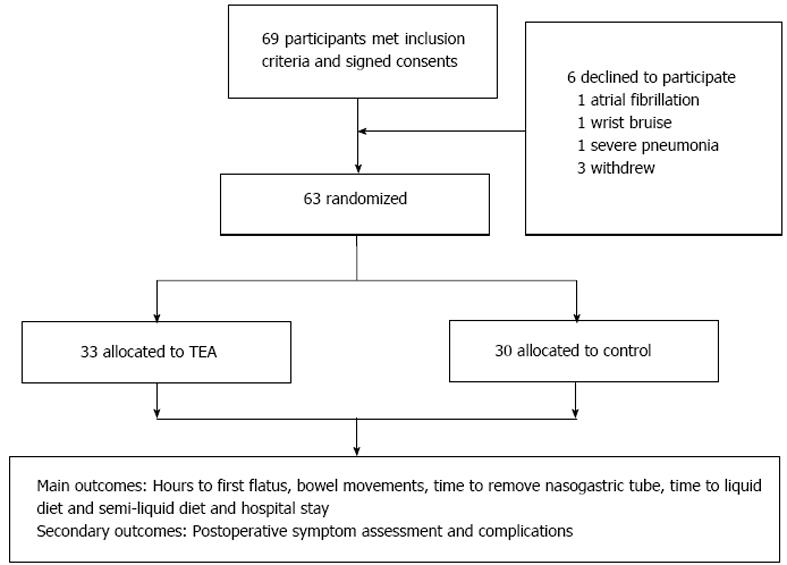

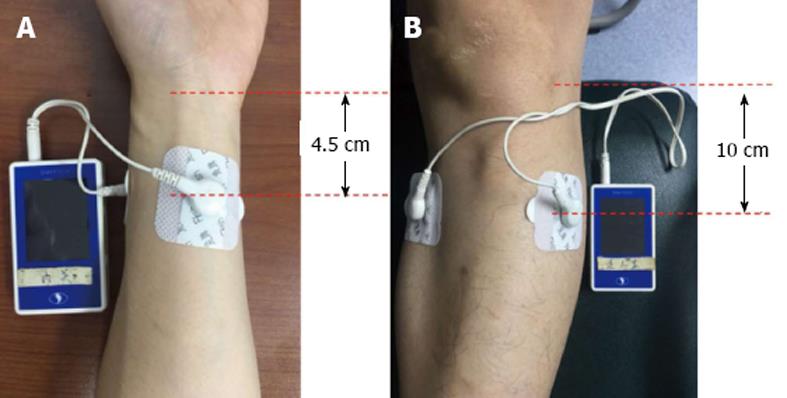

Sixty-nine patients were initially recruited but six declined to participate because of atrial fibrillation (n = 1), wrist bruise (n = 1), severe pneumonia (n = 1) and withdrawal without any reasons (n = 3). The remaining 63 patients were randomly allocated by computer algorithm to the TEA (n = 33) or control (n = 30) group (Figure 1). The TEA group started treatment on on day 1 after surgery, until passing flatus or on day 5. They had 1 h TEA on ST36 and Zusanli (PC6) twice daily in the morning (09:00-10:00) and afternoon (14:00-15:00). The EA sites of ST36 and PC6 were consistent with other studies (Figure 2). The parameters for ST36 were 2 s on, 3 s off, 25 Hz, 0.5 ms, 2-6 mA; while for PC6 it was 0.1 s on, 0.4 s off, 100 Hz, 0.25 ms, 2-6 mA. The electric current was gradually increased just below the patient’s pain threshold, and could be minimally adjusted during the procedure. The patients were allowed to sit even walk during the treatment as long as the TEA was continuously functioning well. The control group received no treatment and without any TEA being binded. The main outcomes were hours to the first flatus or bowel movement, time to nasogastric tube removal, time to liquid and semi-liquid diet, and hospital stay. And the secondary outcomes included postoperative symptom assessment based on each patient’s subjective scale (0-10, including pain, tiredness, nausea, shortness of breath, and wellbeing according to Edmonton Symptom Assessment System), and postoperative complications and hospital stay. Prolonged POI was defined as not passing flatus at > 5 d after surgery.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0, using Student’s t test and χ2 test, and variables were expressed as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

A total of 63 patients (46 male, 17 female, age range: 37-75 years) were recruited and randomized to the TEA group (n = 33) and control group (n = 30). In the TEA group, 23 patients underwent open gastrectomy and 10 underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy. In the control group, 23 patients underwent open gastrectomy and 7 patients underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy. The baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the groups (Table 1). The operating time in the TEA group was 210.79 ± 53.40 min compared with 213.36 ± 69.12 min in the control group (P = 0.868).

| TEA (n = 33) | Control (n = 30) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 63.0 ± 9.70 | 59.0 ± 8.30 | 0.103 |

| Sex (M/F) | 22/11 | 24/6 | 0.183 |

| Chronic gastritis | 8/25 | 9/21 | 0.409 |

| Diabetes | 1/32 | 0/30 | 0.524 |

| Hypertension | 10/23 | 9/21 | 0.599 |

| BMI | 22.32 ± 3.23 | 21.85 ± 3.21 | 0.561 |

| ECOG score (1/2) | 27/6 | 24/6 | 0.553 |

| Preoperative activity level | 1.18 ± 0.392 | 1.17 ± 0.46 | 0.888 |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L) | 40.70 ± 3.38 | 40.08 ± 5.09 | 0.564 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy (Y/N) | 2/31 | 2/28 | 0.657 |

| Surgery (Open/laparoscopic) | 10/23 | 7/23 | 0.369 |

| Surgery (Billroth-I/II/Rou-en-Y) | 10/11/12 | 11/13/6 | > 0.05 |

| Surgery time (min) | 210.79 ± 53.40 | 213.36 ± 69.12 | 0.868 |

| pT staging (T0/1/2/3/4) | 1/7/14/8/3 | 0/8/7/10/5 | - |

| pN staging (N0/1/2/3a/3b) | 1/7/14/8/3 | 11/5/4/10/0 | - |

| Nasal enteral nutrition (Y/N) | 11/22 | 9/21 | 0.496 |

| PCIA/PCEA | 32/1 | 29/1 | 0.833 |

Time to first flatus in the TEA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (73.19 ± 15.61 vs 82.82 ± 20.25 h, P = 0.038), especially for open gastrectomy (76.53 ± 14.29 vs 87.23 ± 20.75 h, P = 0.048). Bowel sounds on day 2 in the TEA group were significantly greater than in the control group (2.30 ± 2.61/min vs 1.05 ± 1.26/min, P = 0.017). For open gastrectomy, bowel sounds on day 2 and day 3 in the TEA group were significantly greater than in the control group (P = 0.006, 0.028, respectively) (Table 2). Time to nasogastric tube removal was earlier in the TEA than control group (4.22 ± 1.01 vs 4.97 ± 1.67 d, P = 0.049). Time to starting liquid diet was shorter in the TEA than control group (5.00 ± 1.34 vs 5.83 ± 2.10 d, P = 0.039). Hospital stay was significantly shorter in the TEA than in the control group (8.06 ± 1.75 vs 9.40 ± 3.09 d, P = 0.041) (Table 2). Then, we excluded patients with complications of pneumonia, chyle leakage and pancreatic leakage, the hospital stay in the TEA group was still significantly shorter compared to the control group (7.73 ± 1.14 vs 8.59 ± 1.67 d, P = 0.026) (Table 2).

| TEA (n = 33) | Control (n = 30) | P value | |

| Time to first flatus (h) | |||

| Total | 73.19 ± 15.61 | 82.82 ± 20.25 | 0.038b |

| Open | 76.53 ± 14.29 | 87.23 ± 20.75 | 0.048b |

| Laparoscopic | 65.52 ± 16.53 | 68.31 ± 9.08 | 0.692 |

| Bowel sound on day 1 (/min) | 0.96 ± 1.80 | 0.63 ± 1.63 | 0.461 |

| Bowel sound on day 2 (/min) | 2.30 ± 2.61 | 1.05 ± 1.26 | 0.017b |

| Bowel sound on day 3 (/min) | 4.30 ± 3.11 | 2.85 ± 2.19 | 0.068 |

| Bowel sound on day 1 (open) (/min) | 0.70 ± 1.29 | 0.70 ± 1.83 | 1.000 |

| Bowel sound on day 2 (open) (/min) | 2.52 ± 2.56 | 0.80 ± 1.0 | 0.006b |

| Bowel sound on day 3 (open) (/min) | 4.74 ± 3.10 | 2.77 ± 2.23 | 0.028b |

| Walk independently (h) | 27.10 ± 15.24 | 36.73 ± 25.91 | 0.074 |

| Walking duration per day (min) | 10.36 ± 6.65 | 9.13 ± 6.16 | 0.452 |

| Remove nasogastric tube (POD) | 4.22 ± 1.01 | 4.97 ± 1.67 | 0.049b |

| Liquid diet (POD) | 5.00 ± 1.34 | 5.83 ± 2.10 | 0.039b |

| Semiliquid diet (POD) | 6.68 ± 1.78 | 7.60 ± 2.33 | 0.087 |

| Hospital stay (POD) | 8.06 ± 1.75 | 9.40 ± 3.09 | 0.041b |

| Modified liquid diet (POD) | 4.73 ± 0.94 (30) | 5.30 ± 1.23 (27) | 0.057 |

| Modified semiliquid diet (POD) | 6.30 ± 1.12 (30) | 7.11 ± 1.74 (27) | 0.039b |

| Modified hospital stay (POD) | 7.73 ± 1.14 (30) | 8.59 ± 1.67 (27) | 0.026b |

There was no significant difference in symptoms between the two groups including pain, tiredness, nausea, shortness of breath and wellbeing (Table 3).

| TEA (n = 33) | Control (n = 30) | P value | |

| Pain on day 1 | 3.79 ± 1.35 | 3.38 ± 1.50 | 0.266 |

| Pain on day 2 | 2.79 ± 1.10 | 2.55 ± 1.08 | 0.391 |

| Pain on day 3 | 2.39 ± 1.20 | 2.14 ± 0.90 | 0.416 |

| Tiredness on day 1 | 5.29 ± 2.13 | 5.42 ± 2.21 | 0.815 |

| Tiredness on day 2 | 4.17 ± 2.01 | 4.53 ± 1.96 | 0.467 |

| Tiredness on day 3 | 3.41 ± 2.58 | 4.33 ± 1.77 | 0.162 |

| Nausea on day 1 | 0.88 ± 1.77 | 0.55 ± 0.90 | 0.352 |

| Nausea on day 2 | 0.49 ± 1.50 | 0.38 ± 0.72 | 0.730 |

| Nausea on day 3 | 0.43 ± 1.72 | 0.32 ± 0.61 | 0.764 |

| SOB on day 1 | 0.73 ± 1.66 | 0.30 ± 0.97 | 0.213 |

| SOB on day 2 | 0.52 ± 1.60 | 0.35 ± 1.33 | 0.657 |

| SOB on day 3 | 0.55 ± 1.74 | 0.19 ± 0.96 | 0.391 |

| Wellbeing on day 1 | 5.97 ± 1.54 | 5.68 ± 1.75 | 0.494 |

| Wellbeing on day 2 | 6.88 ± 1.24 | 6.62 ± 1.57 | 0.469 |

| Wellbeing on day 3 | 7.41 ± 1.69 | 6.83 ± 1.64 | 0.225 |

There was no significant difference in postoperative complications between the two groups (P = 0.270) (Table 4). There was no prolonged ileus in TEA group, while there were three such cases in the control group. An adverse event of bruising on the wrist due to TEA was reported and the patient withdrew from the study. However, there was no severe adverse event.

| TEA (n = 33) | Control (n = 30) | P value | |

| Prolonged postoperative ileus | 0 | 3 | 0.102 |

| Wound infection | 1 | 1 | 0.730 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 0.730 |

| Chyle leakage | 2 | 1 | 0.182 |

| Ventricular premature beat | 1 | 0 | 0.524 |

| Liver impairment | 1 | 0 | 0.524 |

| Pancreatic leakage | 0 | 1 | 0.476 |

| Total | 6 | 7 | 0.270 |

In this prospective and randomized clinical study, we confirmed the role of TEA in the treatment of post-gastrectomy bowel motility recovery for the first time. TEA in gastric cancer patients significantly increased postoperative bowel movement; shortened time to first flatus, nasogastric tube removal, liquid diet and hospital stay, and it was safe.

POI is caused by impaired motility of the whole gastrointestinal tract due to abdominal or extra-abdominal surgery, which is the main reason for symptoms of discomfort and prolonged hospital stay. POI costs $1.5 billion annually in the United States[8]. Pathophysiologically, it is explained by release of inhibitory neural reflexes and inflammatory mediators from the site of injury[1]. However, the complex pathogenesis remains incompletely understood. Treatment for POI includes fasting, nasogastric depression, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, and ambulation. Recent evidence supports that early oral or parenteral nutrition could be an option[2], but for gastric cancer patients, oral nutrition may increase anastomotic leakage rate in the early stage, and parenteral nutrition cannot be tolerated postoperatively. The use of prokinetic agents for treatment of POI is still controversial[3]. In short, there is currently no effective way to accelerate bowel motility recovery.

Acupuncture has been widely used for treatment of gastrointestinal diseases for thousands of years in China, and several studies have demonstrated that it helps gastric and colon cancer patients recover from POI[9,10]. A modern method of EA, which is modified from the traditional acupuncture, also controls postoperative pain and improves gastrointestinal motility after surgery. A randomized controlled trial indicated that EA reduced duration of POI after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer[6]. Animal experiments found that EA at ST36 accelerated colonic motility and transit in freely moving rats[11], and improved restraint-stress-induced delay of gastric emptying central glutamatergic pathways in conscious rats[12]. Jun-fan Fang et al[13] revealed that EA affected the patients by activating the vagus nerve instead of regulating local inflammation. EA also has a therapeutic effect on diabetic gastroparesis[14].

TEA is a new method of electrical stimulation via cutaneous electrodes placed at acupoints without needles. It is a non-invasive method that can be easily accepted by patients and even self-administrated at home. Chen et al[4,15,16] has proved that electroacupuncture improves impaired gastric, small intestinal[17] and colonic[18] motility, ameliorates gastric dysrhythmia[19], and accelerates gastric emptying[5,20], and it is used to treat gastroesophageal reflux, functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome[4]. TEA is effective in treatment of functional dyspepsia[21] and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting[22]. Experiments in dogs have shown that EA and TEA at ST36 both improve the rectal distention-induced impairment of intestinal contraction, transit and slow waves mediated via the vagal mechanism[7], and needleless TEA is as effective as EA in ameliorating intestinal hypomotility[7]. Huang et al[23] investigated the effects of TEA on healthy volunteers, and found that TEA improved impaired gastric accommodation and slow waves induced by cold drinks.

Acupuncture seems promising for treating POI after gastrectomy[9,24] and control of emesis during chemotherapy[25]. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first attempt to investigate the effectiveness of TEA to alleviate POI after gastrectomy. We found that TEA shortened the time to first flatus, along with more bowel sounds on days 2 and 3 in subgroup analysis of patients with open gastrectomy. There may be an approximate correlation between quantity or quality of bowel sounds and bowel function, but it has not been established as a definitive association. Some studies have inserted a Sitz marker capsule into the distal anastomosis to evaluate bowel movements[9,26]. As we noted, bowel sounds became more frequent and louder during the recovery period and increased to more than 2-4/min on days 2 and 3, which could be a good predication of normal bowel function transition.

In contrast, postoperative pain results in stress and affects the mobilization of patients after surgery. Early mobility or activity is recognized as a critical step in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)[27]. The anesthetists would like to perform patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) or patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (PCIA) after surgery in our center, and we routinely give patients analgesics to relieve abdominal pain. As a consequence, the postoperative pain score was < 4 on day 1, and there was no significant difference between the two groups; it gradually decreased to < 3 on days 2 and 3. Several studies have proved that acupuncture or EA reduces pain in patients undergoing thoracic[28], abdominal[6], inguinal hernia surgery[29], breast cancer[30], or kidney[31] surgery. The postoperative patients in our study had less pain because of PCEA or PCIA, most of the patients tolerated pain well, they could even sit up and stand on the morning of day 1 after operation, thus the pain-control availability of TEA was not validated.

Epidural anesthesia might diminish the positive effects of acupuncture by blocking the afferent and efferent neural pathways[32]. Administration of local anesthetic through a thoracic epidural catheter may decrease POI by reducing sympathetic neural input[1]. Based on these reasons, Simon et al[6] excluded patients who received epidural anesthesia or analgesia, and revealed that EA significantly reduced the duration of POI and postoperative analgesic requirement after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Several laboratory and clinical studies have also proved that parasympathetic nerve activity was involved in the process of EA or TEA. Nevertheless, as mentioned before, PCEA or PCIA was routinely used in our center for pain control, which might have affected the outcomes, although there was no significant difference between the two groups.

This study had several limitations. First, the number of patients may have been inadequate to make the results convincing. Second, we did not apply ERAS to the postoperative recovery, which had been proved effective to reduce POI[27]. Third, the mechanisms underlying perioperative gastrointestinal waves or vagal tone associated with TEA should be confirmed in the future. Fourth, it was not a double-blind research, thus we could not exclude the placebo effect.

In conclusion, TEA accelerated bowel movements and alleviated POI and decreased hospital stay after open gastrectomy. It is a safe and convenient treatment for recovery from POI.

Postoperative ileus (POI) after gastrectomy is not rare and causes various symptoms, which probably affects patient recovery, prolongs hospital stay, and increases cost. However, there is no effective way to alleviate POI until now.

Transcutaneous electroacupuncture (TEA) is a new-developed, non-invasive and portable device. It has been validated to improve intestinal dysmotility in dog experiment. But it remains unknown whether it is useful to alleviate POI for post-gastrectomy patients clinically.

The aim of this article was investigating the efficacy and safety of TEA to alleviate POI after gastrectomy.

From April 2014 to February 2017, 63 gastric cancer patients were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China. After gastrectomy, the patients were randomly allocated to the TEA (n = 33) or control (n = 30) group. The patients in the TEA group received 1 h TEA on Neiguan (ST36) and Zusanli (PC6) twice daily in the morning and afternoon until they passed flatus. The main outcomes were hours to the first flatus or bowel movement, time to nasogastric tube removal, time to liquid and semi-liquid diet, and hospital stay. The secondary outcomes included postoperative symptom assessment and complications.

Time to first flatus in the TEA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (73.19 ± 15.61 vs 82.82 ± 20.25 h, P = 0.038), especially for open gastrectomy (76.53 ± 14.29 vs 87.23 ± 20.75 h, P = 0.048). Bowel sounds on day 2 in the TEA group were significantly greater than in the control group (2.30 ± 2.61/min vs 1.05 ± 1.26/min, P = 0.017). Time to nasogastric tube removal in the TEA group was earlier than in the control group (4.22 ± 1.01 vs 4.97 ± 1.67 d, P = 0.049), as well as the time to liquid diet (5.0 ± 1.34 vs 5.83 ± 2.10 d, P = 0.039). Hospital stay in the TEA group was significantly shorter than in the control group (8.06 ± 1.75 vs 9.40 ± 3.09 d, P = 0.041). No significant differences in postoperative symptom assessment and complications were found between the groups. There were no severe adverse events related to TEA.

In this prospective and randomized clinical study, we confirmed the role of TEA in the treatment of post-gastrectomy bowel motility recovery for the first time. TEA in gastric cancer patients significantly increased postoperative bowel movement; shortened time to first flatus, nasogastric tube removal, liquid diet and hospital stay, and it was safe.

The authors proved that TEA was effective and safe to recovery post-gastrectomy patients from POI. So it will probably provide clinical surgeons with a novel non-invasive device to accelerate bowel function recovery and reduce hospital stay, which satisfies the concept of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS). Besides, TEA could be considered to be applied on other abdominal surgeries as well.

| 1. | Mattei P, Rombeau JL. Review of the pathophysiology and management of postoperative ileus. World J Surg. 2006;30:1382-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Holte K, Kehlet H. Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1480-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Traut U, Brügger L, Kunz R, Pauli-Magnus C, Haug K, Bucher HC, Koller MT. Systemic prokinetic pharmacologic treatment for postoperative adynamic ileus following abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD004930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yin J, Chen JD. Gastrointestinal motility disorders and acupuncture. Auton Neurosci. 2010;157:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu S, Hou X, Zha H, Gao Z, Zhang Y, Chen JD. Electroacupuncture accelerates solid gastric emptying and improves dyspeptic symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2154-2159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ng SS, Leung WW, Mak TW, Hon SS, Li JC, Wong CY, Tsoi KK, Lee JF. Electroacupuncture reduces duration of postoperative ileus after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:307-313.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Song J, Yin J, Chen J. Needleless transcutaneous electroacupuncture improves rectal distension-induced impairment in intestinal motility and slow waves via vagal mechanisms in dogs. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4635-4646. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Vather R, Bissett I. Management of prolonged post-operative ileus: evidence-based recommendations. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jung SY, Chae HD, Kang UR, Kwak MA, Kim IH. Effect of Acupuncture on Postoperative Ileus after Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2017;17:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim KH, Kim DH, Kim HY, Son GM. Acupuncture for recovery after surgery in patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acupunct Med. 2016;34:248-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iwa M, Matsushima M, Nakade Y, Pappas TN, Fujimiya M, Takahashi T. Electroacupuncture at ST-36 accelerates colonic motility and transit in freely moving conscious rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G285-G292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Iwa M, Nakade Y, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Electroacupuncture improves restraint stress-induced delay of gastric emptying via central glutaminergic pathways in conscious rats. Neurosci Lett. 2006;399:6-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fang JF, Fang JQ, Shao XM, Du JY, Liang Y, Wang W, Liu Z. Electroacupuncture treatment partly promotes the recovery time of postoperative ileus by activating the vagus nerve but not regulating local inflammation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarosiek I, Song G, Sun Y, Sandoval H, Sands S, Chen J, McCallum RW. Central and Peripheral Effects of Transcutaneous Acupuncture Treatment for Nausea in Patients with Diabetic Gastroparesis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li H, Yin J, Zhang Z, Winston JH, Shi XZ, Chen JD. Auricular vagal nerve stimulation ameliorates burn-induced gastric dysmotility via sympathetic-COX-2 pathways in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen J, Song GQ, Yin J, Koothan T, Chen JD. Electroacupuncture improves impaired gastric motility and slow waves induced by rectal distension in dogs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G614-G620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sun Y, Song G, Yin J, Chen J, Chen JH, Song J, Chen JD. Effects and mechanisms of electroacupuncture on glucagon-induced small intestinal hypomotility in dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1217-1223, e318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jin H, Liu J, Foreman RD, Chen JD, Yin J. Electrical neuromodulation at acupoint ST36 normalizes impaired colonic motility induced by rectal distension in dogs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G368-G376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yin J, Chen J, Chen JD. Ameliorating effects and mechanisms of electroacupuncture on gastric dysrhythmia, delayed emptying, and impaired accommodation in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G563-G570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ouyang H, Yin J, Wang Z, Pasricha PJ, Chen JD. Electroacupuncture accelerates gastric emptying in association with changes in vagal activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G390-G396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu S, Peng S, Hou X, Ke M, Chen JD. Transcutaneous electroacupuncture improves dyspeptic symptoms and increases high frequency heart rate variability in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:1204-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 22. | Zhang X, Jin HF, Fan YH, Lu B, Meng LN, Chen JD. Effects and mechanisms of transcutaneous electroacupuncture on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:860631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang Z, Zhang N, Xu F, Yin J, Dai N, Chen JD. Ameliorating effect of transcutaneous electroacupuncture on impaired gastric accommodation induced by cold meal in healthy subjects. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:561-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hsiung WT, Chang YC, Yeh ML, Chang YH. Acupressure improves the postoperative comfort of gastric cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shin YH, Kim TI, Shin MS, Juon HS. Effect of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy cycle for Korean postoperative stomach cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:267-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chae HD, Kwak MA, Kim IH. Effect of Acupuncture on Reducing Duration of Postoperative Ileus After Gastrectomy in Patients with Gastric Cancer: A Pilot Study Using Sitz Marker. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:465-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Feng F, Ji G, Li JP, Li XH, Shi H, Zhao ZW, Wu GS, Liu XN, Zhao QC. Fast-track surgery could improve postoperative recovery in radical total gastrectomy patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3642-3648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen T, Wang K, Xu J, Ma W, Zhou J. Electroacupuncture Reduces Postoperative Pain and Analgesic Consumption in Patients Undergoing Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:2126416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dalamagka M, Mavrommatis C, Grosomanidis V, Karakoulas K, Vasilakos D. Postoperative analgesia after low-frequency electroacupuncture as adjunctive treatment in inguinal hernia surgery with abdominal wall mesh reconstruction. Acupunct Med. 2015;33:360-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Giron PS, Haddad CA, Lopes de Almeida Rizzi SK, Nazário AC, Facina G. Effectiveness of acupuncture in rehabilitation of physical and functional disorders of women undergoing breast cancer surgery. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2491-2496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tabassi KT, Amini P, Mohammadi S, Razavizadeh RT, Golchian A. The effect of acupuncture on pain score after open kidney surgery. J Complement Integr Med. 2015;12:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meng ZQ, Garcia MK, Chiang JS, Peng HT, Shi YQ, Fu J, Liu LM, Liao ZX, Zhang Y, Bei WY. Electro-acupuncture to prevent prolonged postoperative ileus: a randomized clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aurello P, Luyer MDP, Wu ZQ S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL